Abstract

The present study aimed to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between lung adenocarcinoma and normal lung tissues, and between lung squamous cell carcinoma and normal lung tissues, with the purpose of identifying potential biomarkers for the treatment of lung cancer. The gene expression profile (GSE6044) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database, which included data from 10 lung adenocarcinoma samples, 10 lung squamous cell carcinoma samples, and five matched normal lung tissue samples. After data processing, DEGs were identified using the Student's t-test adjusted via the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Subsequently, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery, and a global network was constructed. A total of 95 upregulated and 241 downregulated DEGs were detected in lung adenocarcinoma samples, and 204 upregulated and 285 downregulated DEGs were detected in lung squamous cell carcinoma samples, as compared with the normal lung tissue samples. The DEGs in the lung squamous cell carcinoma group were enriched in the following three pathways: Hsa04110, Cell cycle; hsa03030, DNA replication; and hsa03430, mismatch repair. However, the DEGs in the lung adenocarcinoma group were not significantly enriched in any specific pathway. Subsequently, a global network of lung cancer was constructed, which consisted of 341 genes and 1,569 edges, of which the top five genes were HSP90AA1, BCL2, CDK2, KIT and HDAC2. The expression trends of the above genes were different in lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma when compared with normal tissues. Therefore, these genes were suggested to be crucial genes for differentiating lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma.

Keywords: lung adenocarcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Lung cancer is a highly prevalent type of cancer (1), and is a leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide (2). In 2012, ~11.9% of cancer cases diagnosed were attributed to lung cancer in Europe (3). In China, lung cancer accounts for 18.5% of cancer cases, and has a mortality rate of 23.1%, ranking it the most prevalent and most lethal among all cancer types (4). Lung cancer is classified as follows: Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-SCLC (NSCLC) (5). Adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and large cell cancer are the three main subtypes of NSCLC (6). Following surgical treatment, the majority of cases of NSCLC will relapse within 5 years; therefore, it is of great importance to fully elucidate the mechanism underlying the progression of NSCLC.

Microarray screening has been used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in cancer samples, in order to better understand the mechanisms underlying cancer development (7). Navab et al (8) identified a prognostic gene-expression signature that contained a subset of 11 genes, which were validated in numerous independent NSCLC gene expression databases. In addition, since lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma exhibit different histology, gene expression levels, particularly the levels of relevant markers such as cytokeratin 5/6, differ between them (9). Therefore, specific genes and microRNAs may be used to distinguish between these two types of cancer (10), and the genetic signatures of these cancer types may differ (11). However, the differences in expression between lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma have yet to be fully elucidated.

The present study used gene expression files downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, compared the DEGs detected between lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma samples, and conducted function and pathway enrichment analyses. In addition, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of the DEGs was constructed. Genes that exhibited higher degrees in the networks were selected as the key genes in the two lung cancer groups.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

The GSE6044 gene expression profile was downloaded from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The profile included data from 10 lung adenocarcinoma samples, 10 lung squamous cell carcinoma samples, and five matched normal lung tissue samples. The microarray data were based on the GPL201 [HG-Focus] platform (Affymetrix Human HG-Focus Target Array; Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Data processing

The raw CEL data were rectified and standardized by Robust Multichip Average using the Affy package in R language (bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/affy.html), in order to obtain the corresponding expression data of the probes. Subsequently, redundant probes that did not correspond with an Entrez Gene ID were deleted, whereas the median value was used for probes that corresponded with several Entrez Gene IDs.

DEGs screening

Student's t-test was used to screen for DEGs in the two types of lung cancer samples. The P-values were further adjusted using the false discovery rate (FDR) approach, according to the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method (12). Genes with a FDR <0.1 and fold change (FC) >1.5 or <0.67 were considered DEGs between the cancer and normal samples.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment

In order to identify the pathways associated with the two cancer groups, tools in the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) (13,14) were used to screen the pathways enriched for in the DEGs from the cancer samples using the Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer score (a modified Fisher's exact t-test) with BH multiple testing correction (12). A KEGG pathway with a BH-corrected P<0.05 was considered to be significantly enriched.

Global network construction of cancer-associated genes

A total of 14 cancer-associated pathways were downloaded from the KEGG database (www.genome.jp/kegg), including colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, glioma, thyroid cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, prostate cancer, endometrial cancer, SCLC and NSCLC. Annotated genes from the 14 pathways were used to construct the global network according to their interaction in pathways by the Cytoscape software (www.cytoscape.org). The expression (upregulated or downregulated) of these genes were further annotated by mapping to the present gene analysis results in two types of lung cancer samples in comparison with normal samples. Subsequently, the enriched DEGs were screened to construct the PPI network in which the interaction relationships between proteins were downloaded from the Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD; www.hprd.org) database (15).

Results

DEGs selection

A total of 8,348 genes were obtained from the GSE6044 gene expression profile. Under the screening criteria of FDR<0.1 and FC >1.5 or P<0.67, 95 upregulated DEGs and 241 downregulated DEGs (up vs. down, 1:3) were detected in the lung adenocarcinoma samples, whereas 204 upregulated DEGs and 285 downregulated DEGs (up vs. down, 1:1.5) were detected in the lung squamous cell carcinoma samples, as compared with the normal lung tissue samples. The majority of DEGs were downregulated in both lung cancer groups.

Significantly enriched pathways in the DEGs from the two lung cancer groups

In order to determine the differences between the two types of lung cancer at the level of related pathways, DAVID was used to conduct pathway enrichment. The DEGs in the lung squamous cell carcinoma group were significantly enriched in the following three pathways: Hsa04110, cell cycle (P=3.93E-06), involving genes YWAQ, MCM3, CHEK2, GADD45 G, RAD21 and PCNA; hsa03030, DNA replication (P=8.50E-06), involving genes MCM3, FEN1, RFC4, POLA1, PCNA and MCM2; and hsa03430, mismatch repair (P=0.01309), involving genes RFC4, MSH6, RFC2 and MSH3.

The DEGs may be involved in the lung adenocarcinoma group by participating in metabolism pathways, including Hsa00010, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (ADH1B, ADH1C, ALDH3A2, LDHA, AKR1A1 and FBP1) and hsa00980, metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 (ADH1B, GSTA3, CYP2F1 and ADH6). However, no significant pathways were enriched when using the cut-off value of BH-corrected P<0.05.

Global network of cancer-associated genes

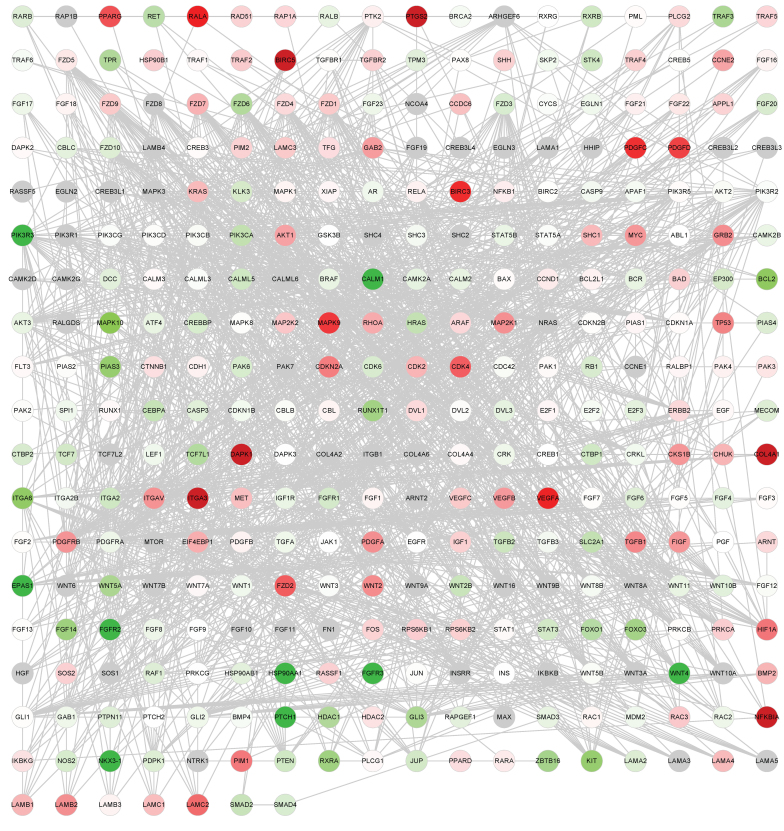

Annotated genes from the 14 cancer-associated pathways downloaded from KEGG were used to construct the global network. There were 341 genes and 1,569 edges (interactions between genes) in the network, as presented in Fig. 1A and B.

Figure 1.

Global network of cancer-associated genes. Cancer network of lung adenocarcinoma samples. Red dots represent upregulated genes; green dots represent downregulated genes. The depth of color represents the extent of the fold change.

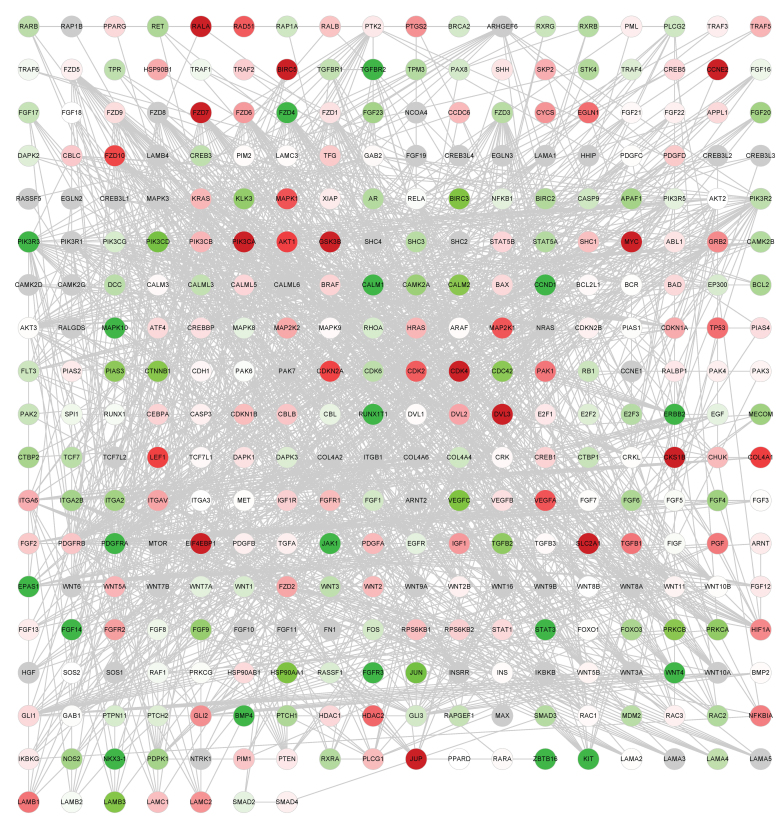

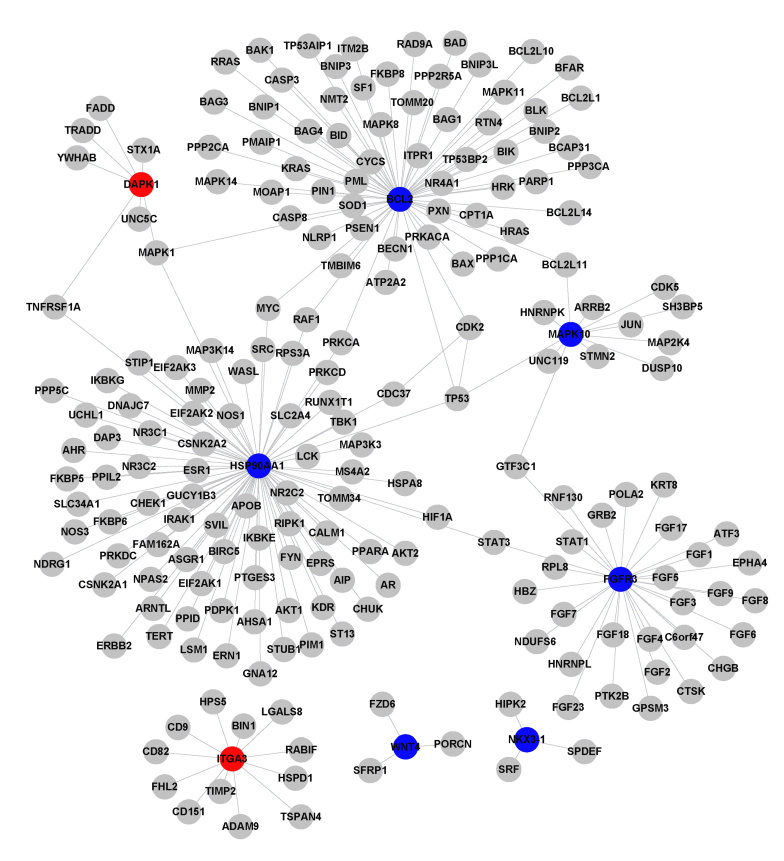

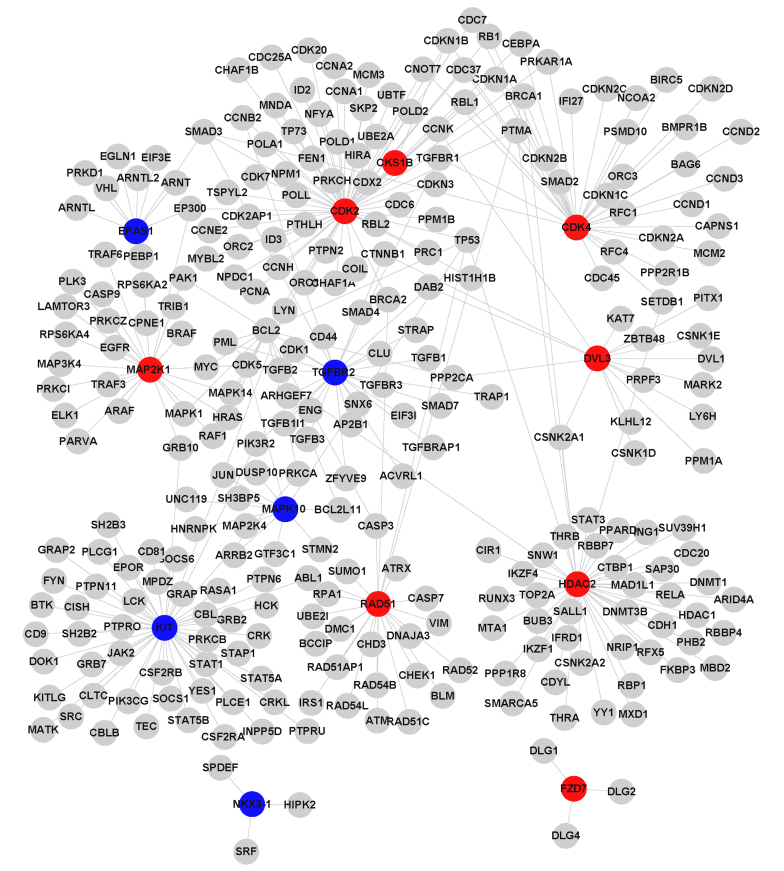

Two upregulated DEGs and seven downregulated DEGs in the adenocarcinoma group, and eight upregulated DEGs and five downregulated DEGs in the squamous cell carcinoma group were selected in the global network under the FDR<0.1 and FC >1.5 or <0.67 criteria. These DEGs were used to construct the PPI network based on the HRPD database; the network consisted of 21 DEGs and 517 relationships with two common genes, NKX3-1 and MAPK10) in Fig. 2A and B. The degrees (number of interacting partners) of the genes in the PPI networks were calculated (Table I), and the top five genes were identified, as follows: HSP90AA1, BCL2, CDK2, KIT and HDAC2, which had degrees of 81, 64, 63, 50 and 46, respectively (Table II). HSP90AA1 exhibited the highest degree, and was the most downregulated gene detected in the adenocarcinoma group. Furthermore, the expression differences of these 19 DEGs were compared between the two types of lung cancer (Table II). The results demonstrated that some genes exhibited similar expression trends between the groups, such as NKX3-1 and MAPK10, whereas DVL3 was upregulated in squamous cell carcinoma samples; however, its expression was not significantly altered in adenocarcinoma samples. The expression of BCL2 was significantly downregulated in adenocarcinoma samples, but not changed in squamous cell carcinoma samples.

Figure 2.

Global network of cancer-associated genes. Cancer network of lung squamous cell carcinoma samples. Red dots represent upregulated genes; green dots represent downregulated genes. The depth of color represents the extent of the fold change.

Table I.

Degrees of the top 10 genes in the protein-protein interaction network.

| Symbol | Degree |

|---|---|

| HSP90AA1 | 81 |

| BCL2 | 64 |

| CDK2 | 63 |

| KIT | 50 |

| HDAC2 | 46 |

| CDK4 | 36 |

| FGFR3 | 30 |

| TGFBR2 | 28 |

| MAP2K1 | 27 |

| RAD51 | 23 |

Table II.

Comparison of 19 differentially expressed genes between the two types of lung cancer.

| Symbol | Gene ID | Adenocarcinoma

|

Squamous cell carcinoma

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dir | FC | BH-P | Dir | FC | BH-P | ||

| FGFR3 | 2261 | −1 | 0.120 | 0.006 | −1 | 0.400 | 0.368 |

| EPAS1 | 2034 | −1 | 0.503 | 0.195 | −1 | 0.290 | 0.040 |

| KIT | 3815 | −1 | 0.591 | 0.565 | −1 | 0.310 | 0.012 |

| NKX3-1 | 4824 | −1 | 0.338 | 0.020 | −1 | 0.348 | 0.029 |

| TGFBR2 | 7048 | 1 | 1.210 | 0.769 | −1 | 0.435 | 0.093 |

| WNT4 | 54361 | −1 | 0.452 | 0.017 | −1 | 0.591 | 0.116 |

| HSP90AA1 | 3320 | −1 | 0.479 | 0.027 | −1 | 0.771 | 0.352 |

| MAPK10 | 5602 | −1 | 0.510 | 0.032 | −1 | 0.577 | 0.064 |

| BCL2 | 596 | −1 | 0.546 | 0.056 | −1 | 0.877 | 0.908 |

| HDAC2 | 3066 | 1 | 1.147 | 0.806 | 1 | 1.751 | 0.037 |

| CDK2 | 1017 | 1 | 1.310 | 0.153 | 1 | 1.809 | 0.056 |

| RAD51 | 5888 | 1 | 1.205 | 0.657 | 1 | 1.812 | 0.048 |

| MAP2K1 | 5604 | 1 | 1.451 | 0.288 | 1 | 1.840 | 0.060 |

| ITGA3 | 3675 | 1 | 2.120 | 0.049 | 1 | 1.008 | 0.981 |

| DVL3 | 1857 | −1 | 0.942 | 0.912 | 1 | 2.279 | 0.066 |

| CDK4 | 1019 | 1 | 1.644 | 0.236 | 1 | 2.799 | 0.004 |

| CKS1B | 1163 | 1 | 1.427 | 0.754 | 1 | 3.061 | 0.040 |

| DAPK1 | 1612 | 1 | 3.083 | 0.095 | 1 | 1.148 | 0.749 |

| FZD7 | 8324 | 1 | 1.325 | 0.792 | 1 | 4.668 | 0.068 |

FC, fold change; BH-P, Benjamini-Hochberg method modified P-value; dir, direction; −1, downregulated expression; 1, upregulated expression; significance was defined as BH-P<0.1 and FC > 1.5 or < 0.67.

Discussion

In the present study, DEGs in lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma samples were screened by comparing gene expression between the cancer samples and normal lung tissue samples. The majority of DEGs were revealed to be downregulated. Compared with lung adenocarcinoma, there were more DEGs in the lung squamous cell carcinoma group. The disheveled homolog DVL3 was upregulated in squamous cell carcinoma and was downregulated in lung adenocarcinoma. Disheveled family proteins have been reported to be associated with the development of cancer, as the cytoplasmic mediators to activate the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway (16). In addition, positive DVL3 expression has previously been detected in NSCLC samples (17). DVL3 has also been identified as a candidate driver for genomic amplification of chromosome 3q26-29 in lung squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Knocking down of DVL3 protein can lead to cell growth inhibition (18) Therefore, DVL3 may be considered a reliable biomarker to distinguish between these two types of lung cancer. Furthermore, BCL2 was downregulated in lung adenocarcinoma; however, it was not detected as a DEG in lung squamous cell carcinoma. It has previously been reported that the BCL2 protein acts as an inhibitor of apoptosis, and its family members, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, are overexpressed in numerous types of tumor cell, including NSCLC (19). Targeted inhibition of BCL2 overcomes the resistance of NSCLC cell lines to chemotherapy (20). However, recent meta-analysis studies suggest BCL2-negative expression is associated with poor prognosis (21,22), indicating its cancer inhibition roles, which was also confirmed by analysis of lung adenocarcinoma samples in the present study.

A PPI network analysis demonstrated that the top five genes were HSP90AA1, BCL2, CDK2, KIT and HDAC2, indicating these genes may be important for lung cancer. These results were consistent with those of previous studies although their roles require further elucidation. The HSP90AA1 gene (generally referred to as HSP90) is located on chromosome 14q32.2 (23). HSP90 is an emerging focus of cancer therapy due to its ability to simultaneously inhibit several signaling pathways (24). Sequist et al (25) reported that a potent inhibitor of HSP90, IPI-504, exerts clinical activity in patients with NSCLC, particularly among patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangements. However, HSP90AA1 was observed to be downregulated in the current study, indicating its underlying tumor suppressor effect, which was also demonstrated by Li et al (26) who identified the expression of HSP90AA1 was lower in nasopharyngeal carcinoma radioresistant cells than that in sensitive cells.

CDK2 is a member of the cyclin-dependent kinases, and inhibition of CDK2 has been reported to induce anaphase catastrophe and lead to apoptosis in NSCLC (27). As expected, CDK2 was also upregulated in the lung cancer samples in the present study, particularly in squamous cell carcinoma. Furthermore, Abrams et al (28) evaluated the activity of the indolinone kinase inhibitor SU11248 against the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT in SCLC; the results suggested that SU11248 may have clinical potential for the treatment of SCLC via direct KIT-mediated antitumor activity. Nevertheless, KIT was downregulated in squamous cell carcinoma in the present study, which may be attributed to the lower malignancy in NSCLC compared with SCLC. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) have been identified as therapeutic targets due to their regulatory function on DNA structure and organization (29). HDAC inhibitors (HDACIs) represent a novel class of anticancer agents. The HDACIs LBH589 (29), trichostatin A (30) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (31) exert profound anti-growth activity against lung cancer cells. In addition, the other DEGs identified in the present study may be considered potential biomarkers for lung cancer therapy.

In conclusion, the present study identifies various crucial genes, including HSP90AA1, BCL2, CDK2, KIT and HDAC2, that display different expression trends in lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma via DEG analysis compared with normal lung tissue and global network construction. These genes may be potential biomarkers for differentiating these two types of lung cancer in clinic.

Figure 3.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks constructed from the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the global network. PPI network of 8 DEGs in lung adenocarcinoma samples. Red nodes represent upregulated genes, whereas blue nodes represent downregulated genes.

Figure 4.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks constructed from the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the global network. PPI network of 13 DEGs in lung squamous cell carcinoma samples. Red nodes represent upregulated genes, whereas blue nodes represent downregulated genes.

References

- 1.Spruit MA, Janssen PP, Willemsen SC, Hochstenbag MM, Wouters EF. Exercise capacity before and after an 8-week multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation program in lung cancer patients: A pilot study. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inamura K, Fujiwara T, Hoshida Y, Isagawa T, Jones MH, Virtanen C, Shimane M, Satoh Y, Okumura S, Nakagawa K, et al. Two subclasses of lung squamous cell carcinoma with different gene expression profiles and prognosis identified by hierarchical clustering and non-negative matrix factorization. Oncogene. 2005;24:7105–7113. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S, Dai M, Ren JS, Chen YH, Guo LW. Estimates and prediction on incidence, mortality and prevalence of lung cancer in China in 2008. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2012;33:391–394. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li S, Huang S, Peng SB. Overexpression of G protein-coupled receptors in cancer cells: Involvement in tumor progression. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1329–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raponi M, Zhang Y, Yu J, Chen G, Lee G, Taylor JM, Macdonald J, Thomas D, Moskaluk C, Wang Y, Beer DG. Gene expression signatures for predicting prognosis of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7466–7472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Palencia A, Gomez-Morales M, Gomez-Capilla JA, Pedraza V, Boyero L, Rosell R, Fárez-Vidal ME. Gene expression profiling reveals novel biomarkers in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:355–364. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navab R, Strumpf D, Bandarchi B, Zhu CQ, Pintilie M, Ramnarine VR, Ibrahimov E, Radulovich N, Leung L, Barczyk M, et al. Prognostic gene-expression signature of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts in non-small cell lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7160–7165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014506108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuta K, Tanabe Y, Yoshida A, Takahashi F, Maeshima AM, Asamura H, Tsuda H. Utility of 10 immunohistochemical markers including novel markers (desmocollin-3, glypican 3, S100A2, S100A7, and Sox-2) for differential diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma of the Lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1190–1199. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318219ac78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamamoto J, Soejima K, Yoda S, Naoki K, Nakayama S, Satomi R, Terai H, Ikemura S, Sato T, Yasuda H, et al. Identification of microRNAs differentially expressed between lung squamous cell carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:456–462. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Yang XY, Shi WJ. Identifying differentially expressed genes and pathways in two types of non-small cell lung cancer: Adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:95–102. doi: 10.4238/2014.January.8.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes W. Benjamini-Hochberg method. In: Dubitzky W, Wolkenhauer O, Cho KH, Yokota H, editors. Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Springer; New York, NY: 2013. p. 78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peri S, Navarro JD, Amanchy R, Kristiansen TZ, Jonnalagadda CK, Surendranath V, Niranjan V, Muthusamy B, Gandhi TK, Gronborg M, et al. Development of human protein reference database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res. 2003;13:2363–2371. doi: 10.1101/gr.1680803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semënov MV, Snyder M. Human dishevelled genes constitute a DHR-containing multigene family. Genomics. 1997;42:302–310. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Q, Zhao Y, Yang ZQ, Dong QZ, Dong XJ, Han Y, Zhao C, Wang EH. Dishevelled family proteins are expressed in non-small cell lung cancer and function differentially on tumor progression. Lung Cancer. 2008;62:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Qian J, Hoeksema MD, Zou Y, Espinosa AV, Rahman SM, Zhang B, Massion PP. Integrative genomics analysis identifies candidate drivers at 3q26-29 amplicon in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5580–5590. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Q, Yang S, Kang MQ. Influence of survivin and Bcl-2 expression on the biological behavior of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:1409–1414. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han ZX, Wang HM, Jiang G, Du XP, Gao XY, Pei DS. Overcoming paclitaxel resistance in lung cancer cells via dual inhibition of stathmin and Bcl-2. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28:398–405. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Wang S, Wang L, Wang R, Chen S, Pan B, Sun Y, Chen H. Prognostic value of Bcl-2 expression in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis and systemic review. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3361–3369. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S89275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao XD, He YY, Gao J, Zhao C, Zhang LL, Tian JY, Chen HL. High expression of Bcl-2 protein predicts favorable outcome in non-small cell lung cancer: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8861–8869. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.20.8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallegos Ruiz MI, Floor K, Roepman P, Rodriguez JA, Meijer GA, Mooi WJ, Jassem E, Niklinski J, Muley T, van Zandwijk N, et al. Integration of gene dosage and gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer, identification of HSP90 as potential target. PLoS One. 2008;3:e0001722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: Combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1113:202–216. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sequist LV, Gettinger S, Senzer NN, Martins RG, Jänne PA, Lilenbaum R, Gray JE, Iafrate AJ, Katayama R, Hafeez N, et al. Activity of IPI-504, a novel heat-shock protein 90 inhibitor, in patients with molecularly defined non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4953–4960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G, Qiu Y, Su Z, Ren S, Liu C, Tian Y, Liu Y. Genome-wide analyses of radioresistance-associated miRNA expression profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma using next generation deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu S, Danilov AV, Godek K, Orr B, Tafe LJ, Rodriguez-Canales J, Behrens C, Mino B, Moran CA, Memoli VA, et al. CDK2 inhibition causes anaphase catastrophe in lung cancer through the centrosomal protein CP110. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2029–2038. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Pryer NK, Cherrington JM. SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng L, Cuneo KC, Fu A, Tu T, Atadja PW, Hallahan DE. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor LBH589 increases duration of gamma-H2AX foci and confines HDAC4 to the cytoplasm in irradiated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11298–11304. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platta CS, Greenblatt DY, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. The HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A inhibits growth of small cell lung cancer cells. J Surg Res. 2007;142:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.12.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komatsu N, Kawamata N, Takeuchi S, Yin D, Chien W, Miller CW, Koeffler HP. SAHA, a HDAC inhibitor, has profound anti-growth activity against non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]