Abstract

Objectives

A 21-gene test that predicts recurrence risk among women with hormone receptor positive (HR+), localized breast cancer was nationally recommended in 2007, but we know little about its subsequent impact. We evaluated (1) patient characteristics associated with test use; (2) correlations between Recurrence Score (RS) and chemotherapy, and; (3) whether test introduction was associated with a reduction in chemotherapy use.

Study Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Methods

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California tumor registry and electronic medical records from 2005–2012 were used to identify HR+, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative, node-negative cancers. Analyses used logistic regression with propensity-score matching and two-level logistic regression.

Results

Of the 7,004 patients who met guidelines for testing, 22% were tested and 26% had chemotherapy. Test use was more likely in younger women (OR 1.22; 95% CI, 1.04–1.44 for 40–49 vs. 50–<65), tumors sized 1.0–2.0 cm (OR 1.20; 95% CI, 1.03–1.40 vs. >2 cm), and women from higher-income neighborhoods (OR 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03–1.07 for each $10,000 increase in area median income). Among patients with low RS, 8% had chemotherapy vs. 72% among patients with high RS (p<0.01). In propensity score-matched analyses, testing was associated with an absolute reduction in the proportion of women receiving chemotherapy of 6.2% (CI: 2.9% to 9.5%); the two-level model showed a similar but non-significant (p=0.14) association.

Conclusion

The 21-gene test is used in a minority of eligible patients in this integrated plan. Its use appears to be associated with a modest decrease in overall chemotherapy use.

AJMC Keywords: cancer care/oncology, personalized medicine, genetics

INTRODUCTION

Genetic testing of tumor cells has the potential to revolutionize the care of cancer patients and to accelerate the benefits of personalized medicine.1 Several studies have observed that this test has diffused in clinical practice and seems to influence chemotherapy decisions.2–6 Recent U.S. studies of claims data and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data found that only 20 to 30% of eligible women in those populations were being tested, with the former study observing that reimbursement by insurers has increased slowly.4,5 It is unknown whether diffusion of this test has been more complete in integrated, fully capitated systems where the costs of care are covered and decisions are less likely to be affected by financial incentives for or against test or chemotherapy use. These tests are potentially costly and may be marketed directly to patients as well as physicians.5,7 As genetic testing in cancer grows more common, health care systems need to systematically evaluate how consistently such tests are being used, and how much incremental benefit they add to baseline clinical practices.8,9

Breast cancer genetic testing provides a useful paradigm for evaluating the impact of such tests at a population level. Decisions about the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for woman with early stage, estrogen or progesterone receptor positive (ER/PR+) breast tumors can be especially difficult since most will never experience a recurrence, even without adjuvant chemotherapy. Currently, several gene-expression profiling tests are being marketed to clinicians and patients as tools to enhance the accuracy of predicting recurrence risk and the likelihood of realizing benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. The 21-gene Oncotype DX (Genomic Health Inc., Redwood City, CA) breast cancer assay has been validated in clinical trials to predict risk of distant recurrence in patients with early stage, node-negative, ER/PR+, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative (HER2−) cancers.10–13 Guidelines for incorporating Oncotype DX testing into treatment decisions were published in 2007.14,15 However, little is known about how this and other genomic tests are diffusing into real-world oncology practice, and how they affect patterns of care.

This study’s overall objective was to assess how the 21-gene test is being used among patients with early stage breast cancer in a large integrated health delivery system. Among patients who met current guidelines for use of this test, our aims were to: (1) compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who had the test with those who did not; (2) describe chemotherapy use among women with test results that indicate low, intermediate and high risk of recurrence; and (3) evaluate whether the introduction of the test was associated with a change in chemotherapy use.

METHODS

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a nonprofit, integrated health care delivery system providing care to over 3.6 million members. Within KPNC, essentially all primary and specialty care and the vast majority of emergency and hospital care are delivered by providers working within a single care system for patients of a single health plan.16

Identification of breast cancers and cancer characteristics

The KPNC tumor registry, a contributor to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of cancer registries, was used to identify all KPNC female members diagnosed with invasive, non-metastatic, incident breast cancer between September 1, 2005 (when significant use of Oncotype DX began at KPNC) and June 30, 2012. The first newly-diagnosed breast cancer during this period was included. The tumor registry includes patient age, sex, diagnosis date, tumor size, node involvement, ER/PR status, stage, and initial chemotherapy treatment. HER2 status was determined using the results of Immunohistochemistry and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization tests.

In 2007, both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) included Oncotype DX testing in their guidelines.14,15 Following NCCN guidelines, we selected women for whom Oncotype DX is to be considered: Women with ER/PR+, HER2−, Stage I and Stage II breast cancers having primary tumors ≥0.51 cm with either no lymph node involvement or only <=2mm axillary node micro-metastases.14 The Oncotype DX assay analyzes the expression of 21 genes to provide a Recurrence Score (RS) corresponding to the risk of distant recurrence at 10 years among tamoxifen-treated patients not treated with chemotherapy.12,13 The RS is classified into three categories based on likelihood of distant recurrence: low risk (RS<18), intermediate risk (RS 18–<31), high risk (RS≥31). Low RS has been shown to predict little benefit from chemotherapy while high RS predicts greater benefit.13 The routine approach in this medical group was to follow NCCN recommendations. Thus, other genetic tests for breast cancer were not commonly used.

Due to the timing of SEER registry reporting requirements, there is some under-ascertainment of the chemotherapy treatment status in the tumor registry. As part of an ongoing prospective study of newly diagnosed breast cancer17, a subset of cases were reviewed to validate the chemotherapy treatment status. Of the 7,004 eligible cancers, 62% were reviewed. Of 1,071 patients validated to have used chemotherapy, 86.18% were correctly classified as such in the registry; of 3,240 patients validated to have not used chemotherapy, 99.97% were correctly classified in the registry. Chemotherapy status used was the validated one, if it existed; otherwise the registry status was used.

Patient characteristics

Persons were assigned to a census block-group (defined by the U.S. 2010 census) based on their home address at the time of cancer diagnosis. Block group income and education were based on the 2006–2010 American Community Survey.18,19 We used data from the year before the cancer diagnosis to create a modified Deyo version of the Charlson comorbidity index.20 From administrative databases, we extracted (from the year before the cancer diagnosis) the following additional variables for each patient for use in the propensity score matching: primary medical center used for care; number of clinic visits and hospital days, and their associated cost.

Analyses

To identify predictors of receiving 21-gene testing, we used logistic regression, in which receipt of the test was the dependent variable and the independent variables were: calendar year of cancer diagnosis (as a categorical variable), age group (5 categories: <40, 40–<50, 50–<65, 65–<75, and 75+ years of age), race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, White Hispanic, White non-Hispanic, Other/unknown), tumor size (3 categories: 0.5cm to ≤1.0 cm, >1.0cm to ≤2.0cm, >2.0cm), comorbidity (3 categories: 0, 1–2, 3+ comorbidities), census block group median income, and proportion of adults in the block group with less than a high school degree.

To assess the potential impact of 21-gene testing on receipt of chemotherapy, we used two different analytic approaches. The first approach evaluated directly whether women who received the test were more or less likely to receive chemotherapy compared to women who were not tested. We ran a logistic regression in which the dependent variable was whether the woman was tested, and the independent variables were the same as those listed above plus the following (to increase further the similarity of the matched cohorts): primary medical center for care; patient’s age-squared (for potential non-linear age effects); cost of clinic and hospital services, and the number of clinic visits and hospital days, in the year before cancer diagnosis. Model calibration and discrimination were good (c statistic: 0.81; Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test: p=0.32, with non-significance reflecting adequate fit). The resulting predicted probability of receiving the test was the patient’s propensity score. We selected patients who received the 21-gene test and matched them one-to-one to patients who were not tested. Matching was performed using the Mahalanobis metric matching within calipers defined as one quarter of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.21 Using this methodology, 93% (n=1,462) of tested women were matched to a non-tested woman, and after matching there were no significant differences between the cohorts with regard to the variables used in the propensity score calculation. However, women in the matched cohorts were younger and had fewer comorbidities than the general pool of women from whom they were drawn. This reflects the fact that among the entire cohort of cancer patients tested women tended to be different from non-tested women.

Using the propensity-matched samples, we calculated the percent of women in each sample receiving chemotherapy, and the corresponding ratio of the odds of receiving chemotherapy among women tested, to the odds of receiving chemotherapy among matched women not tested. As a sensitivity analysis, the matched analysis was repeated among the subset of patients with validated chemotherapy use.

The second analytical approach was to treat the overall percent of women who received testing as a predictive variable for receiving chemotherapy. This approach is similar to “ecological” regression, wherein aggregates are used either in place of, or in addition to, individual-level predictors.22 Unlike an interrupted time-series analysis where differences before and after some change in practice are assessed, this approach does not require us to arbitrarily define time periods as “before” or “after” the introduction of the test, given that testing was phased-in over time. We started with an analytic dataset with one record per woman. For each calendar year and age group, we calculated the percent of women who received the test, and added this variable to the analytic dataset. Thus, a woman diagnosed with cancer in 2011 who was 50–<65 years of age had a variable added her record that reflected the percent of women in her age group in 2011 who were tested. Using these patient-level records, we ran a logistic regression in which receipt of chemotherapy was the dependent variable and the independent variable of interest was the percent of women in the strata who were tested. The woman’s own test status is not included in the model. Other independent variables included in the model were the same as those used in the model identifying predictors of testing. The results of this model were then used to predict the percent of women receiving chemotherapy assuming 1) 0% of women in her age group and year were tested, and 2) assuming 30% were tested (which was about the maximum percent of women who received the 21-gene test in any given year.)

The first approach has been called an “individual-level analysis” and the second approach a “two-level analysis”.22 Each of these approaches has distinct advantages and disadvantages. The individual-level analysis has the advantage of directly measuring the relationship between the individual’s use of the test and their use of chemotherapy, but does not account for certain aspects associated with self-selection of testing. For example, women with a strong predilection for or against chemotherapy may choose not to be tested – a problem similar to “confounding by indication”. The two-level “ecologic” analysis factors out some of the potential unmeasured confounders related to which women choose to be tested.22 However, that approach is prone to bias if there are other unmeasured factors that may have increased or decreased use of chemotherapy at the same time as the increase in the use of testing.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study cohort

We identified 7,004 women diagnosed with cancers meeting our inclusion criteria, and who met guidelines for 21-gene testing (Table 1). The majority of women were under 65 years of age (57%) and 71% were white, non-Hispanic. Three-quarters of cancers were Stage I, and 70% of tumors were > 1.0 cm in size. Overall, 21-gene testing was performed for 22% of women. In adjusted analyses, compared to women 50 to <65 years of age, women 40–<50 years of age were more likely to be tested (Odds Ratio (OR): 1.22; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.04 to1.44), while women 65 to<75 and 75+ were less likely to be tested (OR: 0.42; CI: 0.36 to 0.49, and OR: 0.04; CI: 0.02 to 0.06, respectively)(Table 2). Compared to women with tumors >2.0 cm, women with tumors 0.5cm to ≤ 1.0 cm were less likely to be tested (OR: 0.51; CI: 0.42 to 0.61), while women with tumors >1.0 to ≤ 2.0 cm were more likely to be tested (OR: 1.20; CI 1.03 to 1.40). Each $10,000 increase in block-group median income was associated with increased odds of testing (OR: 1.05, CI: 1.03 to 1.07).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients meeting NCCN guidelines for consideration of the 21-gene test for breast cancer recurrence, and the subgroup of those who received testing. Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Sept 2005 – June 2012a

| Characteristic | Number (%) of breast cancer patients

|

% of all patients receiving 21-gene teste | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allb | Receiving 21-gene testc | Not receiving 21-gene testd | ||

|

|

||||

| Total | 7,004 (100) | 1,567 (100) | 5,437 (100) | 22 |

| Age at diagnosisf | ||||

| <40 | 161 (2) | 61 (4) | 100 (2) | 38 |

| 40–<50 | 944 (13) | 320 (20) | 624 (11) | 34 |

| 50–<65 | 2,922 (42) | 875 (56) | 2,047 (38) | 30 |

| 65–<75 | 1,856 (26) | 293 (19) | 1,563 (29) | 16 |

| 75+ | 1,121 (16) | 18 (1) | 1,103 (20) | 2 |

| Race/Ethnicityf | ||||

| Asian | 967 (14) | 277 (18) | 690 (13) | 29 |

| Black | 401 (6) | 91 (6) | 310 (6) | 23 |

| White, Hispanic | 615 (9) | 135 (9) | 480 (9) | 22 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 4,983 (71) | 1,058 (68) | 3,925 (72) | 21 |

| Other or unknown | 38 (1) | 6 (<1) | 32 (1) | 16 |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 5,226 (75) | 1,178 (75) | 4,048 (74) | 23 |

| II | 1,778 (25) | 389 (25) | 1,389 (26) | 22 |

| Tumor sizef | ||||

| >0.5 cm to <=1.0 cm | 2,069 (30) | 287 (18) | 1,782 (33) | 14 |

| >1.0 cm to <=2.0 | 3,376 (48) | 907 (58) | 2,469 (45) | 27 |

| >2.0 cm | 1,559 (22) | 373 (24) | 1,186 (22) | 24 |

| Comorbidity scoref | ||||

| Low (0) | 5,111 (73) | 1,231 (79) | 3,880 (71) | 24 |

| Intermediate (1–2) | 1,682 (24) | 313 (20) | 1,369 (25) | 19 |

| High (3+) | 211 (3) | 23 (1) | 188 (3) | 11 |

| Initial treatmentsf | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 1,600 (23) | 410 (26) | 1,190 (22) | 26 |

| Radiation therapy | 3,463 (49) | 825 (53) | 2,638 (49) | 24 |

| Hormone therapy | 4,374 (62) | 1,094 (70) | 3,280 (60) | 25 |

Among breast cancer cases meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria for consideration of the 21-gene test (Oncotype DX). See text for inclusion criteria.

Denominator for percent is the number of breast cancer patients in the study cohort (7,004).

Denominator for percent is the number of breast cancer patients receiving 21-gene test (1,567).

Denominator for percent is the number of breast cancer patients not receiving 21-gene test (5,437).

Denominator is the number of breast cancer patients in that demographic/clinical subgroup. For example, among women the 161 women <40 in the cohort, 61 (38%) of them received the 21-gene test.

Patients receiving 21-gene test were significantly different from those not receiving test at p<=0.05, unadjusted.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical predictors of receiving the 21-gene test for breast cancer recurrence, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Sept 2005 – June 2012a

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio of being tested vs. not being tested (95% CI)b |

|---|---|

| Year | |

| 2005 | 0.87 (0.55,1.37) |

| 2006 | REF |

| 2007 | 2.03 (1.52,2.70)* |

| 2008 | 3.53 (2.68,4.64)* |

| 2009 | 3.92 (2.98,5.15)* |

| 2010 | 4.61 (3.53,6.03)* |

| 2011 | 4.59 (3.52,5.98)* |

| 2012 | 3.54 (2.63,4.77)* |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| <40 | 1.34 (0.94,1.89) |

| 40–<50 | 1.22 (1.04,1.44)* |

| 50–<65 | REF |

| 65–<75 | 0.42 (0.36,0.49)* |

| 75+ | 0.04 (0.02,0.06)* |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 1.04 (0.88,1.23) |

| Black | 0.95 (0.73,1.24) |

| Other or unknown | 0.45 (0.18,1.11) |

| White, Hispanic | 0.81 (0.65,1.02) |

| White, non-Hispanic | REF |

| Tumor size | |

| >0.5 cm to <=1.0 cm | 0.51 (0.42,0.61)* |

| >1.0 cm to <=2.0 | 1.20 (1.03,1.40)* |

| >2.0 cm | REF |

| Comorbidity score | |

| Low (0) | 1.35 (0.85,2.16) |

| Intermediate (1–2) | 1.27 (0.79,2.05) |

| High (3+) | REF |

| Census-Block group characteristics | |

| Median incomec | 1.05 (1.03,1.07)* |

| Proportion of adults with less than High School degree | 1.97 (0.99,3.90) |

Among breast cancer cases meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria for consideration of the 21-gene test (Oncotype DX) (n=7004). See text for inclusion criteria.

Odds ratios estimated using multivariate logistic regression. CI=95% confidence interval.

Result reflect odds for each increase of $10,000 in census block median income.

Oncotype DX and chemotherapy use

Among women with 21-gene testing, 52%, 39%, and 9% had low risk, intermediate risk, and high risk RS values, respectively (Table 3). Among women who had the test, a slightly higher percentage (26%) received chemotherapy compared to those who did not (22%, p<0.01). Among women with low, intermediate, and high risk RS, 8%, 40%, and 72%, respectively, received chemotherapy.

Table 3.

Chemotherapy treatment by patient group and 21-gene test Recurrence Score, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Sept 2005 – June 2012a

| Characteristic | Total patients | Percent (n) of patients receiving chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | 7,004 | 23 (1,600) |

| Patients who did not have Oncotype DX testing | 5,437 | 22 (1,190) |

| Patients who had Oncotype DX testing | 1,567 | 26 (410) |

| By Recurrence Scoreb | ||

| Low risk (RS<=18) | 820 | 8 (68) |

| Intermediate risk (RS 18 to <31) | 606 | 40 (241) |

| High Risk (RS 31+) | 141 | 72 (101) |

Among breast cancer cases meeting National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria for consideration of the 21-gene test (Oncotype DX). See text for inclusion criteria.

Differences in the percent of patients receiving chemotherapy among the three Recurrence Score groups was statistically different at p<=01.

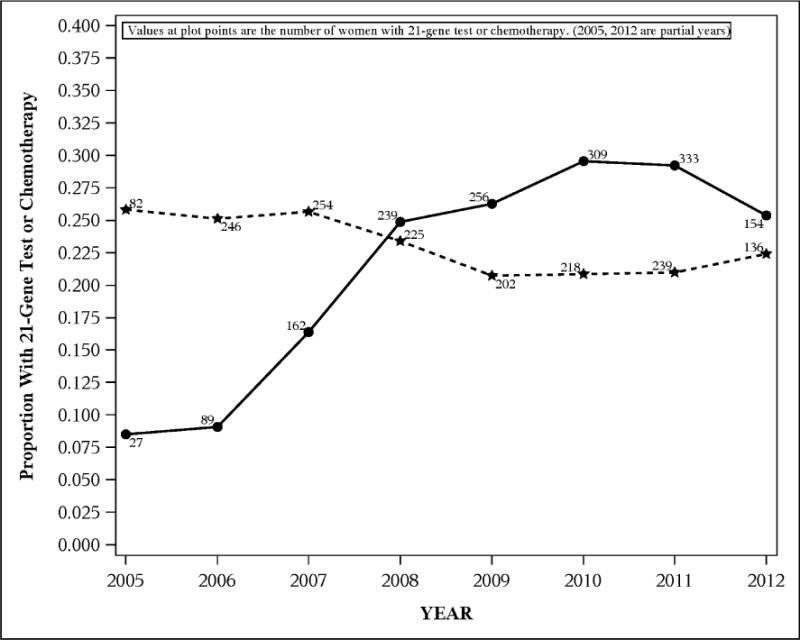

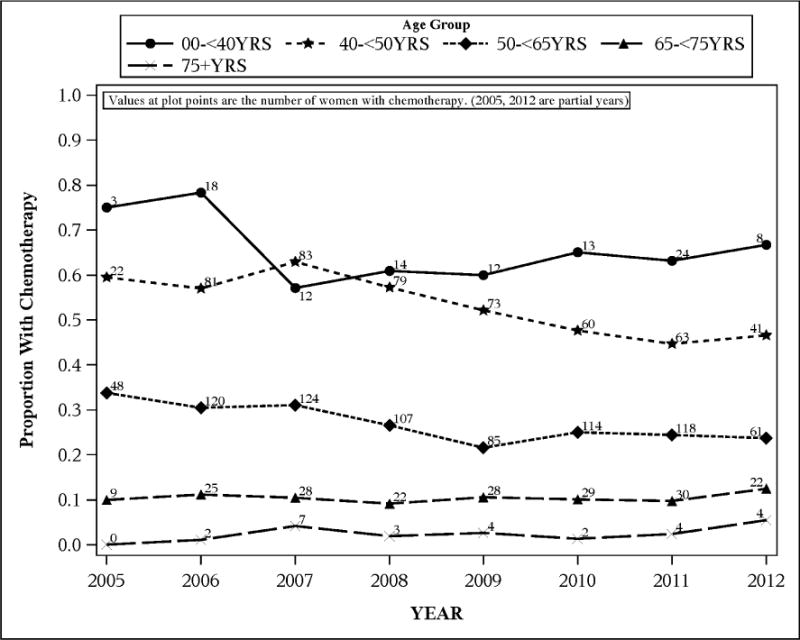

Between 2005 and 2012, the percent of eligible women receiving 21-gene testing rose from 8% to over 25%, while the percent of women receiving chemotherapy decreased modestly from 26% to 22% (Figure 1). Younger women were much more likely to receive chemotherapy, and the two age groups with the most women receiving chemotherapy had the most pronounced downward trends in chemotherapy use from 2005 to 2012 (from 59% to 47% for 40–<50 year olds, and from 35% to 24% for 50–<65 year olds) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Proportion of 7,004 eligible breast cancer patients receiving (a) 21-gene testing (solid line) and (b) chemotherapy (dashed line), by year, Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Figure 2.

Proportion of 7,004 breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, by age group, among those eligible for 21-gene testing, Kaiser Permanente Northern California

In analyses with individual-level propensity score matching (n=2924), receipt of the 21-gene test testing was associated with decreased odds of chemotherapy (OR 0.74; CI: 0.63 to 0.87), corresponding to a reduction in the percent of women receiving chemotherapy from 32.7% to 26.5%, or an absolute reduction of 6.2% (CI: 2.9% to 9.5%). When including only women with validated chemotherapy treatment status, 21-gene testing was associated with a lower odds of chemotherapy (OR:0.64; CI: 0.53 to 0.78) than in the primary analysis, corresponding to an absolute reduction of 9.5% (95% CI: 5.3% to 13.6%). Among this matched cohort, women who had received Oncotype DX testing and went on to receive chemotherapy were older, and were more likely to have Stage 1 cancer and smaller tumors than women who had not received Oncotype DX testing and went on to receive chemotherapy.

In the two-level multivariable (ecological) analysis, each 10% increase in the absolute percent of women tested was associated with a 0.92 decreased odds of chemotherapy, but this result was not statistically significant (CI: 0.83 to 1.03; p=0.14). The point estimates of this model imply that 26% of women in the study would have received chemotherapy in the absence of any testing, while 23% would receive chemotherapy if 30% of women were tested.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first large investigations of the use and impact of the 21-gene test for breast cancer recurrence risk in a managed care population. In this integrated system, we found that while rates of use increased over time, only 20–25% of patients meeting guidelines received testing. In adjusted analyses, use of testing was differential by age, tumor size, and neighborhood-level income. Patterns of chemotherapy use were generally consistent with test results, with those having a low RS far less likely to have chemotherapy than those with a high RS. When used, the test was associated with a modest reduction in overall chemotherapy use.

The rates of testing we observed were similar to other reports from US populations,2,4,5 including those of a large for-profit oncology network.23 One difference from past studies is that we found no racial/ethnic differences in use of the test. For example, Guth et al. found that women treated at municipal hospitals (who were more likely to be of low income and non-white) were less likely to have the 21-gene test than socioeconomically similar women seen in tertiary care settings (3% vs. 30%).24 The fact that the test was fully covered by insurance in our setting removed patient-level financial barriers and may have mitigated racial/ethnic variation in test use. However, patients living in higher income areas were more likely to have the test than those living in lower income areas.

The other clinical and demographic correlates of non-use of 21-gene testing we identified, such as smaller tumor size and older age, have also been observed in other settings.23 For these sub-groups, clinicians and/or their patients may have decided that chemotherapy was not indicated, so that testing would not change treatment decisions. Clinicians may also feel that standard clinicopathologic prognostic factors, existing decision tools (e.g., Adjuvant! www.adjuvantonline.com)25 and/or a patient’s health status or preferences are more important in treatment decision making than 21-gene test results.26 However, it has been reported that, when obtained, the 21-gene results can change pre-testing treatment decisions in about 30–50% of cases.6,27–29 A survey of Kaiser Permanente Northern California oncologists completed in spring 2015 suggests that among those patients who have the 21-gene test, the results cause changes in chemotherapy decisions in approximately 40% – and that these changes are equally divided among changes away from having chemotherapy and changes toward having chemotherapy (T. Lieu, unpublished data).

This 21-gene test and other multigene tests have been promoted as likely to be cost-effective since test costs are expected to be offset by decreases in chemotherapy use among women with low recurrence risk, and hence low benefits of chemotherapy.3,6,30–32 In our matched analysis, we found that testing was associated with a 6–10% reduction in chemotherapy use. A recent meta-analysis estimated a somewhat higher percent reduction of 12%.6 Our “ecologic” analysis indicated that an increase in testing in the KPNC setting from 0% to 30% resulted in approximately a 3% absolute decrease in the percent of women getting chemotherapy. The two-level analysis is a more indirect (and conservative) approach, with fewer observations due to the summarized nature of the analysis, and therefore has less power. Nevertheless, the direction of the result was the same as that of the propensity-score matched analysis. Regardless of approach, our estimated reductions in chemotherapy were far lower than the 31% reduction in chemotherapy observed in a smaller study of a younger cohort in Ireland.3 The lower reduction in chemotherapy we observed relative to other studies was most likely due to our patient population being older and having a lower baseline percent of women receiving chemotherapy, as well as a lower percentage of eligible women being tested compared with the study from Ireland.

Our results should not be construed as suggesting that the 21-gene test is being under-used. Our study evaluated chemotherapy in relation to current levels of testing. Our results cannot be extrapolated to project whether, or by how much, chemotherapy use would decrease if the test were used for a higher percentage of patients. The current level of testing may reflect clinicians’ judgments that the non-tested patients would not benefit from testing because the decision about chemotherapy is already clear in their cases.

Chemotherapy treatment decisions in our study were not always in accord with the RS. Among women with low RS, 8% received chemotherapy anyway, and 28% of those with high RS did not receive chemotherapy. Similar discordant use patterns were noted in a recent meta-analysis.28 Our data did not enable us to determine the reasons for these conflicting choices. However, based on other reports23, it seems that discordant use patterns are not unexpected since multi-gene testing is only one factor in complex chemotherapy decisions, and that test results are not an absolute mandate for or against chemotherapy. For instance, doctors may sometimes use the test to discourage a low risk (based on tumor size, histology, grade) or unhealthy patient who wants chemotherapy from having it, or to encourage treatment in a high risk, healthy patient who does not want it. In the latter situation, a patient may continue to refuse chemotherapy even after receiving a high-risk test result. Genomic testing may increase anxiety and impair decision-making or results may be poorly understood.33–36

This study has many strengths, including its fully enumerated managed care population, inclusion of only those cases with clinical indications for 21-gene testing, and ability to relate test results to chemotherapy use. Although these findings from an integrated health plan population in California may not be representative of all practice settings, the testing and treatment patterns we found were remarkably similar to those reported from other settings.2,23 This suggests that clinical norms, RCT evidence and national recommendations may be more important to physicians ordering behavior than the costs of the test or who is covering those costs. That chemotherapy is sometimes discordant from therapy suggested by the RS indicates that patient factors may be as, or more, important than the health care structure. These hypotheses will need to be tested explicitly in future research across diverse health care systems and populations.

Overall, this study suggests that in a large integrated health care system, the 21-gene test is used in a minority of eligible patients, but when used, it is leading to clinically appropriate patterns of chemotherapy use. Optimizing the benefit and efficiency of this and other genomic tests for cancer patients will require additional research on the factors that drive test use and subsequent decisions about chemotherapy.

Take-away points.

We evaluated the use of a multigene test that predicts recurrence risk in localized breast cancer, and associated trends in chemotherapy use in eligible patients, in this retrospective cohort study.

The multigene test was used in fewer than 1 in 3 eligible patients, with use plateauing in 2010–12.

Recurrence risk scores on the test were highly, but not perfectly, correlated with the use of chemotherapy.

Introduction of the test was associated with a modest decrease in overall chemotherapy use.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant #U01CA183081 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by the following National Cancer Institute grants: R01 CA105274; U19 CA079689; U24 CA171524; U01 CA152958; and UC2 CA148471.

Footnotes

This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

Authors’ contributions: GTR contributed to the design of the study, made substantial contributions to the data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation of data, and was primarily responsible for drafting the manuscript. TAL, JSM, and LAH contributed to the design of the study, made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data, and helped to draft the manuscript and revise it for important intellectual content. SDR, LHK, and YL made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data, and helped to draft the manuscript and revise it for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer: All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

G. Thomas Ray, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, CA.

Jeanne Mandelblatt, Georgetown University Medical Center, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Department of Oncology, Washington, DC.

Laurel A. Habel, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, CA.

Scott Ramsey, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington.

Lawrence H. Kushi, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, CA.

Yan Li, Department of Oncology, Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center, Oakland, CA.

Tracy A. Lieu, Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 2000 Broadway, Oakland, CA.

References

- 1.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):793–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassett MJ, Silver SM, Hughes ME, Blayney DW, Edge SB, Herman JG, et al. Adoption of gene expression profile testing and association with use of chemotherapy among women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2218–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McVeigh TP, Hughes LM, Miller N, Sheehan M, Keane M, Sweeney KJ, et al. The impact of Oncotype DX testing on breast cancer management and chemotherapy prescribing patterns in a tertiary referral centre. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(16):2763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enewold L, Geiger AM, Zujewski J, Harlan LC. Oncotype Dx assay and breast cancer in the United States: usage and concordance with chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(1):149–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts MC, Dusetzina SB. Use and Costs for Tumor Gene Expression Profiling Panels in the Management of Breast Cancer From 2006 to 2012: Implications for Genomic Test Adoption Among Private Payers. J Oncol Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augustovski F, Soto N, Caporale J, Gonzalez L, Gibbons L, Ciapponi A. Decision-making impact on adjuvant chemotherapy allocation in early node-negative breast cancer with a 21-gene assay: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray SW, Cronin A, Bair E, Lindeman N, Viswanath V, Janeway KA. Marketing of personalized cancer care on the web: an analysis of internet websites. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas JS, Phillips KA, Liang SY, Hassett MJ, Keohane C, Elkin EB, et al. Genomic testing and therapies for breast cancer in clinical practice. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(5 Spec):e174–e181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrusi IL, Earle CC, Trudeau M, Leighl NB, Pullenayegum E, Khong H, et al. Closing the personalized medicine information gap: HER2 test documentation practice. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(1):838–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Wale C, Forbes J, Mallon EA, Salter J, et al. Prediction of risk of distant recurrence using the 21-gene recurrence score in node-negative and node-positive postmenopausal patients with breast cancer treated with anastrozole or tamoxifen: a TransATAC study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1829–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habel LA, Shak S, Jacobs MK, Capra A, Alexander C, Pho M, et al. A population-based study of tumor gene expression and risk of breast cancer death among lymph node-negative patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/bcr1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2817–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, Kim C, Baker J, Kim W, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(23):3726–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, Burstein HJ, Carter WB, Edge SB, et al. Invasive breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(2):136–222. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, Norton L, Ravdin P, Taube S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5287–312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selby JV, Smith DH, Johnson ES, Raebel MA, Friedman GD, McFarland BH. Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. Fourth. New York: Wiley; 2005. pp. 241–59. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan ML, Ambrosone CB, Lee MM, Barlow J, Krathwohl SE, Ergas IJ, et al. The Pathways Study: a prospective study of breast cancer survivorship within Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(10):1065–76. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S.Census Bureau. A Compass for Understanding and Using American Community Survey Data: What General Data Users Need to Know. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S.Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD–CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a Control Group Using Multivariate Matched Sampling Methods That Incorporate the Propensity Score. The American Statistician. 1985;39(1):33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston SC. Combining ecological and individual variables to reduce confounding by indication: case study–subarachnoid hemorrhage treatment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1236–41. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Dhanda R, Tseng WY, Forsyth M, Patt DA. Evaluating use characteristics for the oncotype dx 21-gene recurrence score and concordance with chemotherapy use in early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):182–7. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guth AA, Fineberg S, Fei K, Franco R, Bickell NA. Utilization of Oncotype DX in an Inner City Population: Race or Place? Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:653805. doi: 10.1155/2013/653805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivotto IA, Bajdik CD, Ravdin PM, Speers CH, Coldman AJ, Norris BD, et al. Population-based validation of the prognostic model ADJUVANT! for early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2716–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spellman E, Sulayman N, Eggly S, Peshkin BN, Isaacs C, Schwartz MD, et al. Conveying genomic recurrence risk estimates to patients with early-stage breast cancer: oncologist perspectives. Psychooncology. 2013;22(9):2110–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MH, Han W, Lee JE, Kim KS, Park H, Kim J, et al. The Clinical Impact of 21-Gene Recurrence Score on Treatment Decisions for Patients with Hormone Receptor-Positive Early Breast Cancer in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2014 doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson JJ, Roth JA. The impact of the Oncotype Dx breast cancer assay in clinical practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bargallo JE, Lara F, Shaw-Dulin R, Perez-Sanchez V, Villarreal-Garza C, Maldonado-Martinez H, et al. A study of the impact of the 21-gene breast cancer assay on the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer in a Mexican public hospital. J Surg Oncol. 2014;111(2):203–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.23794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hornberger J, Chien R, Krebs K, Hochheiser L. US Insurance Program’s Experience With a Multigene Assay for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 Suppl):e38s–e45s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hornberger J, Alvarado MD, Rebecca C, Gutierrez HR, Yu TM, Gradishar WJ. Clinical validity/utility, change in practice patterns, and economic implications of risk stratifiers to predict outcomes for early-stage breast cancer: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(14):1068–79. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanderlaan BF, Broder MS, Chang EY, Oratz R, Bentley TG. Cost-effectiveness of 21-gene assay in node-positive, early-stage breast cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(7):455–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, Noseworthy T, Tiwana S, Mackean G, Clement F. Experiences and attitudes toward risk of recurrence testing in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(3):457–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2900-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzeng JP, Mayer D, Richman AR, Lipkus I, Han PK, Valle CG, et al. Women’s experiences with genomic testing for breast cancer recurrence risk. Cancer. 2010;116(8):1992–2000. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neill SC, Brewer NT, Lillie SE, Morrill EF, Dees EC, Carey LA, et al. Women’s interest in gene expression analysis for breast cancer recurrence risk. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4628–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo SS, Mumby PB, Norton J, Rychlik K, Smerage J, Kash J, et al. Prospective multicenter study of the impact of the 21-gene recurrence score assay on medical oncologist and patient adjuvant breast cancer treatment selection. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1671–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]