Abstract

Background

Over the last decade, a number of clinical practice guidelines that include guidance for the management of pediatric asthma have been introduced. The consistency across pediatric asthma guidelines is unknown and the emphasis on establishing asthma control may vary. The objective of this paper was to depict the evolution of guidelines for pediatric asthma and to compare current international guidelines in terms of their organization, presentation of evidence and consideration of children, with special emphasis on definitions of asthma control and severity.

Methods

A systematic search to identify asthma guidelines was conducted, and guidelines were searched for pediatric terms. The approaches used by guidelines to define assessments of asthma severity and control were compared between the United States, the Global Initiative for Asthma, Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia.

Results

Pediatric considerations in the management of asthma have been integrated into the various guidelines to different degrees and through varied strategies. There were differences in the conceptual and operational approach used to assess asthma which emphasized either asthma severity or control.

Conclusions

It will be important for future guidelines to clearly define whether the primary assessment parameter is asthma severity or control. Delineating the guideline development process and supporting evidence may improve transparency, consistency and guideline adherence.

Keywords: Asthma control, Asthma severity, Practice guidelines

Introduction

An estimated 300 million individuals worldwide have been diagnosed with asthma [1], which is considered the most common chronic disease among children [2] and affects an average of 10% of children in the European region [3]. Approximately 15 million disability-adjusted life years are lost annually as a result of asthma globally [1], and the total cost attributed to pediatric asthma in the European Union alone is approximately EUR 3 billion [3]. Historically, early asthma guidelines often neglected pediatric considerations despite known differences between children and adults with regard to underlying pathophysiology, symptom patterns and medication efficacy [4].

Asthma guidelines describe pharmacotherapy as a critical component of management in children, stipulating short-acting β-agonists (SABAs; reliever medications) and inhaled corticosteroids (controller medications) to achieve asthma control. SABAs are commonly used in children, but adherence to recommendations for additional medications has been identified as problematic [5–11]. There are effective controller medications and it has been demonstrated that attaining control is a realistic objective [12, 13] resulting in positive health outcomes [14, 15]. Although pediatric issues have gained prominence in some guidelines over the years, suboptimal control remains a problem among children in North America, Europe, Asia and New Zealand [7, 11, 16–25].

The integration of pediatric considerations into asthma guidelines has never been assessed systematically. The objective of this paper was to highlight the evolution of guidelines for pediatric asthma and to compare current international guidelines with respect to assessment of children and approaches to the concepts of asthma severity and control.

Methods

A systematic search of Medline (from 1966 to January week 1, 2006) and Embase (from 1996 to January week 2, 2006) was conducted to identify asthma guidelines using the following Medical Subject Heading terms: asthma, child, child hospitalized, child health services, pediatrics, guidelines (publication type), reference standards and practice guideline. Non-English guidelines were excluded. The most recent guidelines were critically reviewed, as well as the 2 older guideline versions from the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and from the United States (US; referred to as GINA-05, GINA-06, US-02, US-07). The most recent versions were compared with previous versions to determine whether a significant shift in conceptual focus occurred. Any guidelines that were modeled after the GINA guidelines were left out to simplify the comparison. This excluded pediatric guidelines from Japan and South Africa. Guidelines were searched for ‘pediatric’, ‘child’, ‘age’, ‘control’, ‘severity’, ‘evaluation’ and ‘assessment’. Due to the increasing number of tools and guidelines being developed and released to evaluate asthma outcomes, it becomes increasingly important to systematically assess the differences and similarities between these recommendations both historically and geographically. The notion of a growing focus on asthma control versus severity has been identified, but requires a more critical evaluation across the guidelines, which has not yet been conducted to the knowledge of the authors. Consequently, recommendations for assessment of asthma in children were reviewed and compared with respect to an emphasis on asthma severity or asthma control.

Results

Organization of Pediatric Recommendations

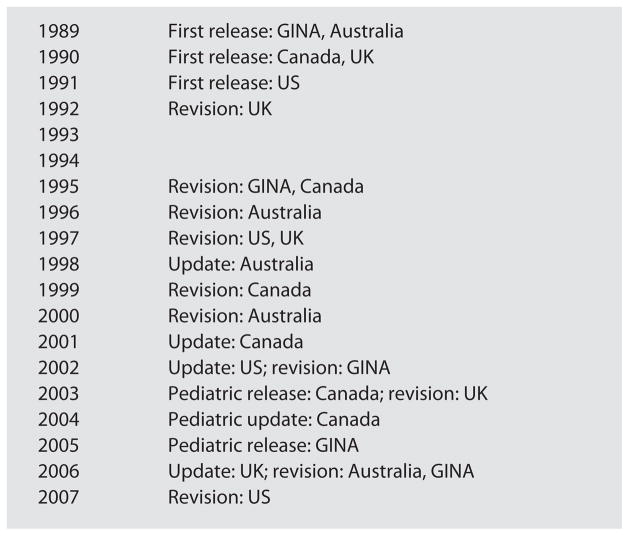

Widely cited guidelines published in English included those from the US, GINA, Canada, the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia. These are presented chronologically in figure 1. In 2003, Canada was first to create asthma guidelines directed exclusively towards children, which were updated to include the literature until 2004 [26]. In 2005, GINA introduced the Pocket Guidelines for Children [27] which were revised in 2006 [28]. The UK [29], Australia [30] and the US [31, 32] added chapters for children to their adult guidelines or updated specific recommendations throughout the guidelines to reflect the pediatric literature. Therefore, several different approaches to addressing pediatric considerations have been implemented, which may influence the uptake of pediatric recommendations by clinicians.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of asthma guidelines. First release = First release of asthma guidelines for the jurisdiction; revision = a new revised guideline was released; update = the previous guideline was updated based on new relevant literature; pediatric release = first release of asthma guidelines directed towards children; pediatric update = pediatric guidelines were updated based on new relevant literature.

Framework to Analyze Guideline Asthma Assessments

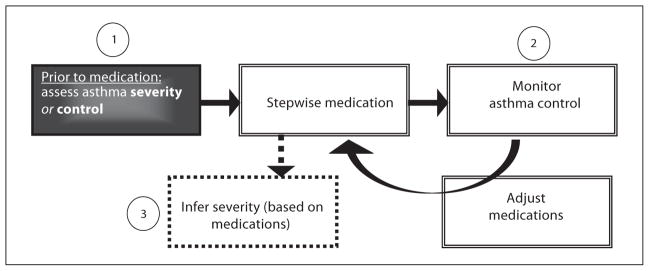

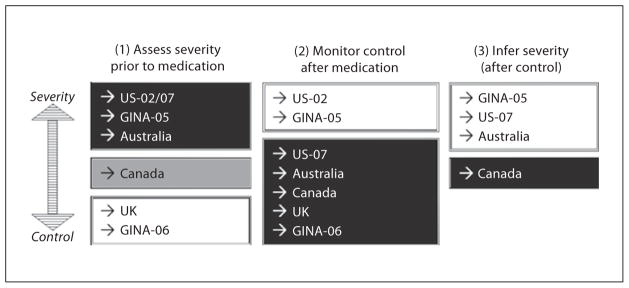

Figure 2 outlines 3 stages of guideline recommendations that address the relationship between pharmacotherapy and the assessment of asthma. These steps include: (1) assessing asthma severity prior to medication; (2) monitoring asthma control after medications have been initiated, and (3) inferring asthma severity based on medication dosage requirements after control has been achieved. All of the guidelines specified that the main goal was to achieve control. There was consensus among the guidelines that a treatment continuum be used consisting of stepwise adjustments tailored to each child based on the level of control attained. Figure 3 depicts the different guideline approaches to the stages of asthma assessment outlined in figure 2. Each guideline either emphasized (darker boxes) or de-emphasized (lighter boxes) the importance of stage 1, 2 or 3. The following 3 sections will critically review conceptual and operational differences between the guidelines.

Fig. 2.

Framework for stages of assessment of asthma.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of stages of assessment of asthma across guidelines.

Stage 1: Assessing Asthma Prior to Controller Medications

Guidelines from US-02, US-07, GINA-05, Australia and Canada provided detailed recommendations for the initial assessment of asthma severity, while the UK and GINA-06 guidelines did not consistently specify severity levels to determine medication dosages. The GINA-06 guidelines stated simply that medications should be initiated according to the child’s needs without specifying criteria. The GINA-06 guidelines referred to the detailed severity levels previously defined in the GINA-05 version for ‘research purposes only’. The UK guidelines labeled the first medication step as ‘mild intermittent’, but provided no criteria to define this severity level. For the second medication step in the UK guidelines involving the introduction of a ‘regular preventer therapy’, it was recommended that the initial dose of inhaled corticosteroids be ‘appropriate to the severity of the disease’, and the following criteria were provided: exacerbation in the last 2 years, SABA ≥3/week, symptomatic ≥3/week, nighttime waking 1/week. Beyond these first 2 medication steps, no further severity levels or criteria were mentioned. In contrast, other guidelines stated that a controller therapy should be introduced at the level of ‘mild persistent’ (US-02 and GINA-05) or ‘mild’ (Canada, US-07), which represented 1 of 4 or 5 severity levels that were clearly differentiated and associated with specific medication regimens.

The levels of severity were directly compared between the US-02, GINA-05, Canadian, Australian and US-07 guidelines (table 1). The US-02 and GINA-05 guidelines were the most focused on measures of severity to inform drug therapy and provided detailed descriptions for 4 levels of severity, ranging from mild intermittent to severe persistent, each clearly associated with stepped levels of medication requirements (table 1). The US-07 guidelines provided 4 levels of severity similar to the earlier version, although the lowest level of severity in the previous 2002 guidelines was revised from ‘mild intermittent’ to ‘mild’ in order to stress that serious exacerbations are possible even among children with intermittent asthma [32]. Likewise, Australia included 4 similar levels of severity, but subdivided intermittent asthma into ‘infrequent’ and ‘frequent’ and did not directly associate severity with medication steps for children as was done in the US-02 and US-07 guidelines. The 2004 Canadian guidelines were less clear in that they stated that ‘severity is more difficult to assess and may only be determined after control is achieved’, but graphically illustrated medication steps associated with different levels of severity. It was also stated that for the initial assessment of asthma, previous severity levels were still applicable from the 1999 Canadian guidelines, which described 5 levels of severity associated with distinct medication steps (table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment categories and associated medication recommendations for children of 5 years and older

| Guideline | Severity assessment | Medication steps: preferred treatmentb |

|---|---|---|

| US-02 |

|

|

| GINA-05a |

|

|

| Canada 2003 | medication steps illustrated graphically

|

previous guidelines from 1999 referenced

|

| US-07 |

|

|

| Australia 2006 |

|

not directly associated with severity levels

|

| GINA-06 | referenced GINA-05 severity levels for research purposes only |

|

| UK 2005 |

|

|

ICS = Inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β-agonist; CS = corticosteroid; LTRA = leukotriene receptor antagonist.

These definitions are based on the GINA-05 guidelines and are referenced in the GINA-06 guidelines for research purposes only.

All guidelines recommend SABA as needed at step 1.

As shown in table 2, the clinical endpoints considered in the US-02, GINA-05, Canadian, Australian and US-07 guidelines included the frequency of night-time symptoms and lung function. All of the guidelines except the Canadian guidelines included daytime symptoms. The GINA-05 guidelines incorporated the impact of exacerbations on activity, whereas the Australian and US-07 guidelines considered the frequency of exacerbations. The US-07 and Canadian guidelines included endpoints for SABA utilization and activity limitations. Additional endpoints in the Canadian guidelines related to recent hospital admissions and previous near fatal episodes, which differentiated these guidelines in terms of their scope for the assessment of severity.

Table 2.

Severity criteria clinical endpoints: US, GINA-05, Canada and Australia guidelines

| Severity | US-02a | GINA-05b | Canada | Australiac | US-07 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Mild intermittent | Intermittent | Very mild | Infrequent intermittent | Frequent intermittent | Intermittent | |

| Night-time symptoms | ≤2/month | ≤2/month | infrequent symptoms | none | none | ≤2/month | |

| PEF/FEV1 predicted, other lung function | ≥80% predicted, <20% PEF variability | ≥80% predicted, <20% PEF variability | normal | >80% predicted, <20% PEF variability | at least 80% predicted, <20% PEF variability | normal FEV1 between exacerbations FEV1 >80% predicted FEV1/FVC >85% (normal for children ≥12 years) |

|

| Daytime symptoms | ≤2 week | <1/week, asymptomatic | infrequent symptoms | none | none | ≤2 week | |

| Other criteria | normal PEF between attacks | need SABA <3 times/week | brief, mild exacerbations, <every 4–6 weeks | >2 exacerbations/month | SABA ≤2 weeks for symptom control no interference with normal activity exacerbations = 0–1/year |

||

| Level 2 | Mild persistent | Mild persistent | Mild | Mild persistent | Mild persistent | ||

| Night-time symptoms | >2/month | >2/month | 0 to + | >2/month and not every week | 3–4/month | ||

| PEF/FEV1 predicted, other lung function | ≥80% predicted, <20 to 30% PEF variability | ≥80% predicted, <20 to 30% PEF variability | >80% predicted | at least 80% predicted, 20–30% PEF variability | FEV1 >80% predicted FEV1/FVC >80% (normal for children ≥12 years) |

||

| Daytime symptoms | >2/week and <1/day | >1/week and <1/day | >1/week and <1/day | >2/week but not daily | |||

| Other criteria | attacks may affect activity | need SABA every 8 h or more 0 to + limitation daily activities 0 previous near fatal episodes 0 recent hospital admissions |

exacerbations may affect activity and sleep | SABA >2/week for symptom control (but not >1/day for children ≥12 years) minor limitation with normal activity exacerbations ≥2/year |

|||

| Level 3 | Moderate persistent | Moderate persistent | Moderate | Moderate persistent | Moderate persistent | ||

| Night-time symptoms | >1/week | >1/month | + | >1/week | >1/week but not nightly | ||

| PEF/FEV1 predicted, other lung function | >60 to<80% predicted, >30% PEF variability | >60 to <80% predicted, >30% PEF variability | 60–80% predicted | 60–80% predicted, >30% PEF variability | FEV1 60–80% predicted FEV1/FVC 75–80% (FEV1/FVC reduced by 5% for children ≥12 years) |

||

| Daytime symptoms | daily | daily | daily | daily | |||

| Other criteria | attacks affect activity | need SABA every 4–8 h + to ++ limitation daily activities 0 previous near fatal episodes 0 recent hospital admissions |

exacerbations at least twice per week exacerbations restrict activity or affect sleep |

SABA daily for symptom control some limitation with normal activity exacerbations ≥2/year |

|||

| Level 4 (and 5) | Severe persistent | Severe persistent | Severe | Very severe | Severe persistent | Severe persistent | |

| Night-time symptoms | frequent | frequent | +++ | frequent | often 7/week | ||

| PEF/FEV1 predicted, other lung function | ≤60% predicted, >30% PEF variability | ≤60% predicted, >30% PEF variability | <60% predicted | ≤60% predicted | ≤60% predicted, >30% PEF variability | FEV1 <60% predicted FEV1/FVC <75% (FEV1/FVC reduced by >5% for children ≥12 years) |

|

| Daytime symptoms | continual | continuous | frequent symptoms | continual | throughout the day | ||

| Other criteria | limited physical activity | need SABA every 2–4 h +++ limitation daily activities + previous near fatal episode + recent hospital admission |

frequent exacerbations exacerbations restrict activity |

SABA several times per day for symptom control extremely limited normal activity exacerbations ≥2/year |

|||

PEF = Peak expiratory flow; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC = forced vital capacity; SABA = short-acting β-agonist.

These criteria for pulmonary lung function do not apply to children <5 years in the US guidelines.

These definitions are based on the GINA-05 guidelines and are referenced in the GINA-06 guidelines for research purposes only. These guideline criteria apply only to children >5 years (no criteria are provided for children <5 years).

These criteria apply only to children >5 years.

In terms of the threshold values that defined each clinical endpoint, all of the aforementioned guidelines had a high level of agreement in terms of the lung function cutoff values at each level of severity. For example, a score between 60 and 80% of predicted for a test using peak expiratory flow or forced expiratory volume in 1 s classified children as ‘moderate persistent’ (Australia, GINA-05, US-02 and US-07) or ‘moderate’ (Canada). For nighttime symptoms, the cut-offs were slightly more strict in the GINA-05 guidelines than in the US-02, US-07 and Australian guidelines, while all 4 guidelines recommended that the overall level of severity be guided by the worst result among the individual endpoints. For example, if a child experienced night-time symptoms more than once a week, which is one of the criteria for ‘moderate persistent’ severity, but had daytime symptoms and lung function at the level of ‘mild persistent’, then the child’s asthma severity would be classified as ‘moderate persistent’. In the Canadian guidelines, levels of severity were depicted using graphic symbols that represented the frequency of the event (ranging from 0 to +++) and could not be compared directly with other guidelines.

The US-02 and GINA-05 guidelines included notes stating that children with ‘mild intermittent’ asthma who had experienced severe exacerbations should be treated with a controller medication, the use of which was associated with ‘mild persistent’ asthma. Therefore, although not explicit, the occurrence of a severe exacerbation moved the severity assessment from ‘mild intermittent’ to ‘mild persistent’. The Australian guidelines were more clear and included exacerbations as a clinical endpoint, labeling the asthma of any child that demonstrated ‘brief, mild exacerbations’ less than every 4–6 weeks as ‘infrequent intermittent’, while more than 2 exacerbations per month leading to the introduction of a controller medication was classified as ‘frequent intermittent’. In the Canadian guidelines, near fatal episodes were one of the clinical endpoints in the assessment of baseline severity, where a single + sign for a near fatal episode indicated that the child’s asthma was severe and dictated a higher dose of controller medication as well as an additional medication such as a long-acting β-agonist. Alternatively, the US-07 guidelines defined exacerbation as requiring an oral systemic corticosteroid. In these guidelines, fewer than 2 exacerbations was considered intermittent asthma, and anything greater was classified as persistent asthma. However, a note cautioned that there were insufficient data to correspond exacerbation frequency to severity level. Overall, there were several inconsistencies across the guidelines in the number of levels, the types of endpoints included or the thresholds that defined levels of severity, as well as the inclusion of exacerbations for the baseline assessment of severity. The guidelines did agree on the basic need to define severity in stage 1, including consistent evaluation of night-time symptoms, very similar lung function cut-offs at each level of severity, and a conservative approach to classifying severity based on the worst individual endpoint.

Stage 2: Monitoring Asthma Control to Adjust Medications

Across all guidelines, asthma control was a multi-dimensional concept defined by several parameters which are summarized in table 3. There was consensus among the guidelines that it was necessary for a child to satisfy all of the control parameters in order to attain acceptable asthma control. If acceptable control was not attained, then guidelines agreed to ‘step up’ the medication level, whereas stepping down was recommended to determine the lowest level of therapy needed to maintain control. Differences between the guidelines in the definitions of asthma control levels are discussed below.

Table 3.

Asthma control parameters

| Parameter | US-02 | GINA-05 | Canada, 2003 | Australia, 2006 | US-07 | UK, 2005 | GINA-06 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime symptoms | minimal or none | minimal or no symptoms, including night-time symptomsa | <4 days/week | none | ≤2 days/week but not more than once on each day | minimal | none (≤2/week) |

| Night-time symptoms | minimal or none | <1 night/week | not woken | ≤1/month (<2/month for children ≥12 years) | minimal | none | |

| Need for SABA | minimal | minimal (>1 canister/ month is poor control)a | <4 doses/week | none | ≤2 days/week | minimal | none (twice or less/week) |

| Lung function | maintain (near) normal pulmonary functiona | nearly normal (>80% personal best consistently)a | ≥90% of personal best FEV1 or PEF | normal (FEV1/FVC and PEF are separate parameters)a | FEV1 or peak flow >80% predicted or personal best FEV1/FVC >80%a | normal (>80% predicted or best of FEV1 or PEF)a | nearly normal (>80% personal best consistently)a |

| Physical activity | no limitations | no limitationsa | normal | normal | no interference with normal activity | no limitations | limitations of activities: none |

| Exacerbations | minimal or none | minimala | mild, infrequent | none | 0–1/year | none | none |

| Adverse effects from medications | minimal or none | minimal or nonea | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Absences from work or school | no school missed and no parents missed work | NA | none | none | NA | NA | NA |

| Lung function variation | NA | NA | <10 to 15% of PEF diurnal variation | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Urgent care | NA | no emergency visits to physicians or hospitalsa | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; PEF = peak expiratory flow; FVC = forced vital capacity; NA = not assessed; SABA = short-acting β-agonist.

These criteria were omitted for children <5 years of age or ‘younger children’.

The US-02, GINA-05, Canada and UK guidelines provided clear definitions of ‘acceptable’ control (table 3). In addition to delineating acceptable (and unacceptable) control, the Australian, US-07 and GINA-06 guidelines provided an intermediate classification to further discriminate between children, emphasizing the focus on control in these guidelines. The GINA-06 guidelines promoted a cycle of observing and adjusting medications by monitoring asthma control and specified 3 levels of asthma control: controlled (all control parameters satisfied), partly controlled (failure of any one control parameter) and uncontrolled (3 out of 6 control parameters satisfied or 1 exacerbation in any week). Similarly, the US-07 and Australian guidelines defined 3 levels of control (US-07: well controlled, not well controlled and very poorly controlled; Australia: good, fair, poor). Specific cut-points for each parameter were provided; however, there were differences in these cut-points across guidelines, with the highest level of control defined most strictly by the Australian guidelines, followed by GINA-06 and US-07, respectively.

In terms of the parameters used to assess asthma control, all of the guidelines included parameters for daytime symptoms, night-time symptoms, the need for SABA, lung function, physical activity limitations and exacerbations. Adverse effects were also incorporated in the US-02 and the GINA-05 guidelines, while school absences were included in the US-02, Canadian and Australian guidelines. Emergency department visits were unique to the GINA-05 guidelines and were excluded from the GINA-06 revision. A parameter for lung function variation was unique to the Canadian guidelines.

Many of the parameters were described in qualitative terms, and the wording was often inconsistent across the guidelines. Table 4 illustrates the variation across guidelines in the definition of the exacerbation parameter. Definitions ranged from ‘mild, infrequent exacerbations’ (Canada) to ‘minimal exacerbations’ (GINA-05) to ‘no exacerbations’ (UK). The different ways in which these definitions were interpreted in published studies are also presented in table 4, which illustrates that the time frame used to assess an exacerbation varied from the past month to the past year. The GINA-06 guidelines were the first to specify a time frame. Lastly, all of the guidelines presented the control parameters as equally weighted, except the GINA-06 guidelines which separated the exacerbation parameter from the 5 others to stress its importance and stated that an exacerbation in any given week automatically classified that week as uncontrolled (regardless of other parameters), whereas in the absence of an exacerbation, uncontrolled asthma required that at least 3 control parameters be unattained. Preventing exacerbations is becoming understood and accepted as an important predictor of disease activity [33]. Overall, there was variation between the guidelines in the number of parameters, the type of parameters, the language used to describe each parameter, as well as the emphasis on exacerbations. It is important to emphasize that the main goal in all of the guidelines was to achieve asthma control which was consistently based on a multi-dimensional concept including the parameters daytime symptoms, night-time symptoms, the need for SABA, lung function, physical activity limitations and exacerbations. Furthermore, the failure to achieve ‘acceptable’ asthma control reliably defined the need to step up the medication level.

Table 4.

Guideline definitions of ‘exacerbations’ and interpretations in the literature

| Reference | Definition of exacerbation for achieving acceptable control | Time frame | Age, years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretation of Canadian guidelines goal of ‘mild, infrequent exacerbation’ | |||

| Boulet et al. [14], 2004 | infrequent exacerbations (poor control = any exacerbations) | unknown | 18+ |

| Chapman et al. [19], 2001 | infrequent exacerbations (poor control = any exacerbations) | past month | 4+ |

|

| |||

| Interpretation of GINA goal of ‘minimal exacerbation’ | |||

| Bateman et al. [13], 2001 | no exacerbations | 95% of 8-week period | 7 studies: >12, 1 study: 4–11 |

| Bateman et al. [15], 2002 | no exacerbations based on case record forms | at least 7 of 8 weeks | >12 |

| Bateman et al. [12], 2004 | no deterioration in asthma requiring treatment with an oral corticosteroid or an emergency department visit or hospitalization | 8 weeks | 12–80 |

| De Marco et al. [83], 2003 | no exacerbations | past year | 20–44 |

| Kuehni et al. [22], 2002 | no severe attack | past year | 4–16 |

| Lai et al. [24], 2003 | sleep disruption at least once a week | past month | <16 |

| Rabe et al. [25], 2004 | no hospital admissions, hospital emergency department visits, or unscheduled emergency department visits to other health care facilities | past year | <16 |

| Soriano et al. [44], 2003 | no severe episodes of asthma | past month | 16+ |

|

| |||

| Interpretation of US guidelines goal of ‘minimal or no exacerbation’ | |||

| Carlton et al. [17], 2005 | no urgent care, emergency department or hospital visits | past 3 months | <18 |

|

| |||

| Interpretation of UK guidelines goal of ‘no exacerbation’ | |||

| Watson et al. [11], 2005 | no exacerbations requiring emergency care or oral steroids | 1 year | 0–18 |

Stage 3: Inferring Asthma Severity after Control Is Attained

Only the GINA-05, Canadian, Australian and US-07 guidelines included stage 3, where it was recommended to infer the severity level based on the dosage/types of medications that were required to achieve asthma control. This is in contrast to directly evaluating clinical endpoints in stage 1. The GINA-05 guidelines included a statement that ‘the step system for classifying asthma severity takes into account the treatment the patient is currently receiving’, although no further details were specified. In the Canadian guidelines, the specific medication combinations corresponding to each level of inferred severity for stage 3 were clearly documented and given greater priority over the stage 1 assessment. In the Australian guidelines, the evaluation of severity in stage 1 based on clinical characteristics was proposed to guide ‘rational selection of initial therapy’, while an evaluation of severity based on the types and dosages of medications required to achieve ‘good’ asthma control was intended to illustrate the interaction between control and severity. The US-02 guidelines were criticized for excluding an assessment of severity based on the minimal medication requirement to maintain control [34], which was incorporated into the US-07 guidelines for the purposes of population level assessments, clinical research or overall severity evaluations for well-controlled patients with ‘optimal therapy’. Emphasizing stage 3 is in line with a focus on control. It stresses the importance of adjusting medications to achieve control and assessing underlying severity when the child is fully controlled.

Discussion

Conceptual Differences in the Assessment of Asthma in Children: An Evolution towards Asthma Control

The literature suggests that asthma control and severity are distinct concepts. Asthma control involves the adequacy of management [35, 36], which may vary markedly over short time periods [17, 37–40] and should entail short-term evaluations of current asthma status [37], burden [39] and medical management [38, 40]. Unlike control, asthma severity is defined as a relatively stable [17, 37, 40] underlying characteristic of the individual [37], which represents the pathophysiology of the disease [35–37]. Findings from the present review reinforce that each guideline branded their assessment of asthma by emphasizing either asthma control or severity [41]. Based on the 3 stages of assessment, the guidelines were classified according to decreasing emphasis on asthma severity and the increasing focus on control: US-02, GINA-05, Canada, UK, US-07, Australia and GINA-06. Table 5 positions the guidelines on a horizontal continuum based on this conceptual focus extending from asthma severity to control.

Table 5.

Summary of asthma severity and control parameters

| Parameter |

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US-02

|

GINA-05

|

Canada

|

UK

|

US-07

|

Australia

|

GINA-06

|

||||||||

| severity | control | severitya | control | severity | control | severity | control | severity | control | severity | control | severity | control | |

| Daytime symptoms | + | + | + | + | ~ | + | NA | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + |

| Night-time symptoms | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + |

| Lung function | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + |

| Need for SABA | ~ | + | ~ | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | ~ | + | NA | + |

| Exacerbations | ~ | + | ~ | + | ~ | + | NA | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + |

| Physical activity or limitations on daily activities | ~ | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + |

| Absence from school | ~ | + | ~ | ~ | ~ | + | NA | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | + | NA | ~ |

| Lung function variation | ~ | + | + | ~ | ~ | + | NA | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | NA | ~ |

| Adverse effects | ~ | + | ~ | + | ~ | ~ | NA | ~ | b | b | ~ | ~ | NA | ~ |

| ED visit or hospital admission | ~ | ~ | ~ | + | + | ~ | NA | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | NA | ~ |

| Current treatment | ~ | ~ | +b | ~ | +b | ~ | NA | ~ | ~ | ~ | +b | ~ | NA | ~ |

| Previous life-threatening attack | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | + | ~ | NA | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | NA | ~ |

ED = Emergency department; SABA = short-acting β-agonist.

The severity category is based on the GINA-05 guidelines, which are recommended for research purposes only in the GINA-06 guidelines.

This parameter applies exclusively if pharmacotherapy has been initiated.

Earlier guidelines, such as the US-02 and GINA-05, emphasized the assessment of severity to inform medication choices, while guidelines from Canada and the UK stressed the importance of assessing control and were less clear about the recommendations for assessing severity. However, only the 3 most recent guidelines, US-07, Australia and GINA-06, defined 3 separate levels of control, indicating a shift from the traditional focus on severity to control. Unlike the US-02 version, the US-07 guidelines clearly distinguished that once a patient has started therapy (long-term controller medication), asthma control should be assessed to adjust medications which can subsequently be correlated to underlying severity levels, while clinical severity assessments were reserved for initial evaluations in patients without or prior to long-term controller medications. The Australian guidelines were very similar to the US-07 guidelines, although the emphasis on control was clearly dictated: ‘control is most relevant to the day-to-day care of a patient with asthma in general practice or in the pharmacy.’ The GINA-06 guidelines go even further to emphasize asthma control, stating that ‘asthma control is more relevant and useful’ because severity concerns the underlying disease severity which may vary over time, as well as the responsiveness to treatment. Further, the absence of severity levels in stage 1 in GINA-06 signified a considerable shift from the GINA-05 guidelines, where the stage 1 severity assessment provided the central focus to inform medication regimens.

This growing emphasis on control reinforces the components of chronic disease management, such as regular evaluation, achieving target outcomes and tailored therapy [12, 39, 42, 43]. This approach acknowledges that severity is a determinant of asthma control [38, 40, 42] but does not dictate the means to achieve it [44]. It supports the possibility to have severe asthma that is well controlled, or conversely, mild asthma that is not well controlled [17, 40, 41], as patients classified as having mild asthma may report impaired quality of life [43]. Focusing on control may improve patient perceptions and expectations that are commonly low in children [16, 25, 45, 46], caregivers [22] and clinicians [15, 46, 47]. This may in turn improve symptom reporting by children and parents [16] and treatment decisions by clinicians [12, 13, 25, 47].

However, a complete focus on control, such as that advocated by the GINA-06 guidelines, which do not recommend that clinicians use the levels of severity in children prior to prescribing controller medications, implies that all children would be started with a low-dose controller medication despite differences in their asthma severity. This approach reflects a more gradual strategy that requires repeated visits to the physician for modifications to pharmacotherapy which may take longer to achieve asthma control. Further, the goal to manage or control asthma may diminish the ideal of treating the underlying inflammation [41, 42] to decrease long-term lung function impairment or to prevent future exacerbations. Therefore, despite the benefits of focusing on asthma control, comprehensive guidelines for the preliminary assessment of asthma may be important for the initial medication prescription in order to achieve control swiftly.

Operational Inconsistencies within and between Guidelines

Although the conceptual differences between control and severity have received much attention, there is no agreement regarding the optimal strategy to measure asthma control and severity [40, 41, 43, 48, 49]. Table 5 highlights the overlapping endpoints recommended for the assessment of severity and control across many of the guidelines. Currently, control parameters are used as indirect measures of airway inflammation [40, 41], due to challenges in directly assessing severity. Improved methods to evaluate asthma inflammation, such as exhaled nitric oxide, tests of bronchial hyper-responsiveness [41], bronchial biopsy [50], bronchoscopy or induced sputum [41], have not been validated for therapeutic decisions [51–55] and are currently under evaluation [50]. Lung function measures provide the most objective measure of asthma control, offering indirect insight into the degree of inflammation [41]. However, it is difficult for children, especially those under the age of 5 years [31, 56, 57], to produce reliable lung function measurements [58, 59] because the tests require active cooperation of the child [57]. Results from forced expiratory volume in 1 s are often reported at near-normal values among symptomatic or hospitalized children [42, 60–66]. For these reasons, lung function parameters for young children were excluded from many guidelines including the US-02, UK, GINA-06, US-07 (under the age of 5 years) and Australia (under the age of 7 years), while the Canadian guidelines acknowledged the lack of optimal pulmonary function tests in children. For older children, all of the guidelines included lung function parameters to assess severity and/or control. Some evidence suggests that excluding lung function tests may lead to the overestimation of asthma control [67] or underestimation of severity [68]. Nonetheless, lung function thresholds have been criticized and require further evaluation in children [42, 60, 61, 65, 66].

Inconsistencies across the guidelines in their definitions of asthma severity and control often cause confusion [35, 37, 38, 41], which makes it difficult for clinicians and researchers to categorize patients and consistently evaluate disease status [43, 59, 69, 70], resulting in variable reporting of control at the population level [13, 71]. It will be important for future guidelines to develop comprehensible parameter definitions and operational tools to facilitate consistent clinical assessment by physicians. An important observation in the more recent guidelines was the growing support for asthma control surveys, which were recommended and have been reviewed be Yawn et al. [41, 42]: Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (GINA-06, US-07) [37, 72, 73], Asthma Control Questionnaire (Australia, GINA-06, US-07) [36], Asthma Control Test (Australia, GINA-06, US-07) [74] and the Asthma Control Scoring System (GINA-06) [75]. These tools offer a quick and efficient way to evaluate control in the clinic, although more research may be required to determine the optimal questionnaire for children in order to improve overall standardization. Currently, many clinicians depend on 1 measure to assess asthma, such as daytime symptoms [11, 37, 40, 41], which has been associated with a significant overestimation of control or an underassessment of severity [46, 47] and can lead to ineffective treatment [41] as well as suboptimal outcomes [6, 76]. It is critical to assess the validity of multiple endpoints to discriminate between patients with different medication needs. A standardized assessment based on the main parameters that appear across the guidelines (daytime symptoms, night-time symptoms, need for SABA, exacerbations and physical activity limitations) may be necessary to achieve consistent stepwise pharmacotherapy. Parameters less consistently included in the guidelines, such as adverse effects from medications, lung function variation and absences from school, must be critically evaluated to determine their relative impact on control levels and pharmacotherapy modifications.

Conclusions

There has been progress away from consensus opinion and towards evidence-based guidelines for asthma [77], although the need for multicenter international clinical trials of the effectiveness of guideline recommendations remains [78].

It is critical that the unique challenges associated with pediatric asthma management are addressed. Furthermore, the process used to develop recommendations for the assessment of asthma severity and control in children needs to be transparent [41]. Assessment recommendations need to be linked explicitly to the supporting evidence [79]. This will allow physicians to independently appraise the relative validity of the various recommendations [80], which may improve adherence and help identify areas that require further research. These approaches may reduce ambiguity and inconsistency in current guidelines and allow pediatric asthma outcomes to be compared across jurisdictions, thereby enhancing international harmonization and reducing asthma-related morbidity and mortality. Despite the conceptual and operational differences between the pediatric asthma guidelines, the overall goal for children to achieve asthma control through a stepwise treatment continuum based on the evaluation of multi-dimensional outcomes is consistently advocated across the guidelines, which will improve asthma management if implemented.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study and for Ms. Cope was provided as a grant from Allergen NCE, one of the Network of Centres for Excellence.

References

- 1.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. Global burden of asthma: executive summary of the Global Initiative for Asthma Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy. 2004;59:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Taking action on asthma. [accessed July 1, 2007];Report of the Chief Medical Officer of Health. 2000 http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/pub/ministry_reports/asthma/asthma_e.pdf.

- 3.van den Akker-van Marle ME, Bruil J, Detmar SB. Evaluation of cost of disease: assessing the burden to society of asthma in children in the European Union. Allergy. 2005;60:140–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Asthma. [accessed July 1, 2007];Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention (updated 2005) 2005 http://www.ginasthma.org/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=1169.

- 5.Reeves MJ, Bohm SR, Korzeniewski SJ, Brown MD. Asthma care and management before an emergency department visit in children in Western Michigan: how well does care adhere to guidelines? Pediatrics. 2006;117:118–126. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2000I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braganza S, Sharif I, Ozuah PO. Documenting asthma severity: do we get it right? J Asthma. 2003;40:661–665. doi: 10.1081/jas-120019037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermeire PA, Rabe KF, Soriano JB, Maier WC. Asthma control and differences in management practices across seven European countries. Respir Med. 2002;96:142–149. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diette GB, Skinner EA, Markson LE, Algatt-Bergstrom P, Nguyen T, Clark RD, et al. Consistency of care with national guidelines for children with asthma in managed care. J Pediatr. 2001;138:59–64. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams RJ, Fuhlbrigge A, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Livingston JM, Weiss KB, et al. Use of inhaled anti-inflammatory medication in children with asthma in managed care settings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:501–507. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piecoro LT, Potoski M, Talbert JC, Doherty DE. Asthma prevalence, cost, and adherence with expert guidelines on the utilization of health care services and costs in a state Medicaid population. Health Serv Res. 2001;36:357–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson L, Kerstjens HA, Rabe KF, Kiri V, Visick GT, Postma DS. Obtaining optimal control in mild asthma: theory and practice. Fam Pract. 2005;22:305–310. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, Busse WW, Clark TJ, Pauwels RA, et al. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:836–844. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateman ED, Bousquet J, Braunstein GL. Is overall asthma control being achieved? A hypothesis-generating study. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:589–595. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17405890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulet LP, Thivierge RL, Bellera C, Dorval E, Collet JP. Physicians’ assessment of asthma control in low vs. high asthma-related morbidity regions. J Asthma. 2004;41:813–824. doi: 10.1081/jas-200038426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman ED, Frith LF, Braunstein GL. Achieving guideline-based asthma control: does the patient benefit? Eur Respir J. 2002;20:588–595. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00294702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt S, Kljakovic M, Reid J POMS Steering Committee. Asthma morbidity, control and treatment in New Zealand: results of the Patient Outcomes Management Survey (POMS), 2001. NZ Med J. 2003;116:U436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlton BG, Lucas DO, Ellis EF, Conboy-Ellis K, Shoheiber O, Stempel DA. The status of asthma control and asthma prescribing practices in the United States: results of a large prospective asthma control survey of primary care practices. J Asthma. 2005;42:529–535. doi: 10.1081/JAS-67000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stempel DA, McLaughin TP, Stanford RH, Fuhlbrigge AL. Patterns of asthma control: a 3-year analysis of patient claims. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:935–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman KR, Ernst P, Grenville A, Dewland P, Zimmerman S. Control of asthma in Canada: failure to achieve guideline targets. Can Respir J. 2001;8(suppl A):35A–40A. doi: 10.1155/2001/245261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Asthma in Canada: a landmark study (pediatric version) Mississauga: GlaxoSmithKline; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health Agency of Canada. [accessed July 1, 2007];The prevention and management of asthma in Canada: a report from the National Asthma Control Task Force. 2000 http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/pma-pca00/index.html.

- 22.Kuehni CE, Frey U. Age-related differences in perceived asthma control in childhood: guidelines and reality. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:880–889. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00258502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabe KF, Vermeire PA, Soriano JB, Maier WC. Clinical management of asthma in 1999: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Europe (AIRE) study. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:802–807. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.16580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, Kuo SH, Mukhopadhyay A, Soriano JB, et al. Asthma control in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:263–268. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabe KF, Adachi M, Lai CK, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, Weiss KB, et al. Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults: the global asthma insights and reality surveys. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker A, Berube D, Chad Z, Dolovich M, Ducharme F, D’Urzo T, et al. Canadian Pediatric Asthma Consensus guidelines, 2003 (updated to December 2004) CMAJ. 2005;173(suppl 6):S12–S14. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Global Initiative for Asthma. [accessed July 1, 2007];Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention in children. 2005 http://www.ginasthma.org/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=1171.

- 28.Global Initiative for Asthma. Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention in children, revised 2006. Medical Communications Resources Inc; 2006. [accessed July 1, 2007]. http://www.gin-asthma.com/Guidelineitem.asp??l1=2&l2=1&intId=49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. [accessed July 1, 2007];British guideline on the management of asthma. 2005 http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign63.pdf.

- 30.National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma Management Handbook. Melbourne: National Asthma Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy S, Bleecker ER, Boushey H, Busse W, Clark NM. Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Federico M, Wamboldt F, Carter R, Mansell A, Wamboldt M. History of serious asthma exacerbations should be included in guidelines of asthma severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liard R, Leynaert B, Zureik M, Beguin FX, Neukirch F. Using Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines to assess asthma severity in populations. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:615–620. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16d08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cockcroft DW, Swystun VA. Asthma control versus asthma severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:1016–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:902–907. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, Sanocki LL, Fitterman L, Berger M, et al. Association of asthma control with health care utilization and quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1647–1652. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9902098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osborne ML, Vollmer WM, Pedula KL, Wilkins J, Buist AS, O’Hollaren M. Lack of correlation of symptoms with specialist-assessed long-term asthma severity. Chest. 1999;115:85–91. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. Attaining optimal asthma control: a practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vollmer WM. Assessment of asthma control and severity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:409–413. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colice GL. Categorizing asthma severity: an overview of national guidelines. Clin Med Res. 2004;2:155–163. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yawn B, Brenneman SK, Allen-Ramey FC, Cabana MD. Assessment of asthma severity and asthma control in children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:322–329. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman KR. Impact of ‘mild’ asthma on health outcomes: findings of a systematic search of the literature. Respir Med. 2005;99:1350–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soriano JB, Rabe KF, Vermeire PA. Predictors of poor asthma control in European adults. J Asthma. 2003;40:803–813. doi: 10.1081/jas-120023572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fuhlbrigge AL, Guilbert T, Spahn J, Peden D, Davis K. The influence of variation in type and pattern of symptoms on assessment in pediatric asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;18:619–625. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boulet L, Phillips R, O’Byrne P, Becker A. Evaluation of asthma control by physicians and patients: comparison with current guidelines. Can Respir J. 2002;9:417–423. doi: 10.1155/2002/731804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halterman JS, Yoos HL, Kaczorowski JM, McConnochie K, Holzhauer RJ, Conn KM, et al. Providers underestimate symptom severity among urban children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:141–146. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ehrs PO, Aberg H, Larsson K. Quality of life in primary care asthma. Respir Med. 2001;95:22–30. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker A. [accessed July 1, 2007];Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines (presentation) 2003 http://www.cnac.net/english/PaedaticGuidelines(ASED7).pdf.

- 50.Sont JK. How do we monitor asthma control? Allergy. 1999;54(suppl 49):68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1999.tb04391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosias P, Dompeling E, Mieke AD, Pennings HJ, Hendriks H, Van Iersel M, et al. Childhood asthma: exhaled markers of airway inflammation, asthma control score, and lung function tests. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38:107–114. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colon-Semidey A, Marshik P, Corwley M, Katz R, Kelly HW. Correlation between reversibility of airway obstruction and exhaled nitric oxide levels in children with stable bronchial asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30:385–392. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200011)30:5<385::aid-ppul4>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Covar R, Szefler SJ, Martin R. Relations between exhaled nitric oxide measures of disease activity among children with mild-to-moderate asthma. J Pediatr. 2003;142:469–475. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Napier E, Turner S. Methodological issues related to exhaled nitric oxide measurement in children aged four to six years. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;38:107–114. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pijnenburg M, Hofhuis W, Hop W, De Jongste J. Exhaled nitric oxide predicts asthma relapse in children with clinical asthma remission. Thorax. 2005;60:215–218. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.023374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gorelick MH, Stevens MW, Schultz T, Scribano PV. Difficulty in obtaining peak expiratory flow measurements in children with acute asthma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:22–26. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000106239.72265.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beyden N, Pin I, Matran R. Pulmonary function tests in preschool children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:640–644. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-449OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. [accessed October 17, 2008];Global Initiative for Asthma. 2005 (updated 2005) available at: http://www.ginasthma.com/Guidelineitem.asp??l1=2&l2=1&intId=60.

- 59.Sharek PJ, Mayer ML, Loewy L, Robinson TN, Shames RS, Umetsu DT, et al. Agreement among measures of asthma status: a prospective study of low-income children with moderate to severe asthma. Pediatrics. 2002;110:797–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paull K, Covar R, Jain N, Gelfand EW, Spahn JD. Do NHLBI lung function criteria apply to children? A cross-sectional evaluation of childhood asthma at National Jewish Medical and Research Center, 1999–2002. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39:311–317. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger DT, White D, Lemanske RF, Sorkness CA. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:426–432. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eid NS, Yandell B, Howell L, Eddy M, Sheikh S. Can peak expiratory flow predict airflow obstruction in children with asthma? Pediatrics. 2000;105:354–358. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Horak E, Grassl G, Skladal D, Ulmer H. Lung function and symptom perception in children with asthma and their parents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35:23–28. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spahn JD, Cherniack R, Paull K, Gelfand EW. Is forced expiratory in one second the best measure of severity in childhood asthma? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:784–786. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1234OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klein R, Fritz G, Yeung A, McQuaid E, Mansell A. Spirometric patterns in childhood asthma: peak flow compared with other indices. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:372–379. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jenkins HA, Cherniack R, Szefler SJ, Covar R, Gelfand EW, Spahn JD. A comparison of the clinical characteristics of children and adults with severe asthma. Chest. 2003;124:1318–1324. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nair SJ, Daigle KL, DeCuir P, Lapin CD, Schramm CM. The influence of pulmonary function testing on the management of asthma in children. J Pediatr. 2005;147:797–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stout JW, Visness CM, Enright P, Lamm C, Shapiro G, Gan VN, et al. Classification of asthma severity in children: the contribution of pulmonary function testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:844–850. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kemp JP. Guidelines update: where do the new therapies fit in the management of asthma? NHLBI and WHO Global Initiative for Asthma. Drugs. 2000;59(suppl 1):23–28. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller MK, Johnson C, Miller DP, Deniz Y, Bleecker ER, Wenzel SE. Severity assessment in asthma: an evolving concept. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:990–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fuhlbrigge AL, Adams R, Guilbert TW, Grant E, Lozano P, Janson SL, et al. The burden of asthma in the United States: level and distribution are dependent on interpretation of the national asthma education and prevention program guidelines. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1044–1049. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skinner EA, Diette GB, Algatt-Bergstrom P, Nguyen TT, Clark RD, Markson LE, et al. The Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) for children and adolescents. Dis Manag. 2004;7:305–313. doi: 10.1089/dis.2004.7.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, Frazier EA, Berger M, Buist AS. Association of asthma control with health care utilization: a prospective evaluation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:195–199. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.2102127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.LeBlanc A, Robichaud P, Lacasse Y, Boulet L. Quantification of asthma control: validation of the Asthma Control Scoring System. Allergy. 2007;62:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolfenden L, Diette G, Krishnan J, Skinner EA, Steinwachs D, Wu A. Lower physician estimate of underlying asthma severity leads to undertreatment. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:231–236. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McFadden ER. A century of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:215–221. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-185OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bousquet J. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and its objectives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30(suppl 1):2–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument. London: St. George’s Hospital Medical School; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Davis D, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. CMAJ. 1997;157:408–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Marco R, Bugiani M, Cazzoletti L, Carosso A, Accordini S, Buriani O, et al. The control of asthma in Italy. A multicentre descriptive study on young adults with doctor diagnosed current asthma. Allergy. 2003;58:221–228. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]