Abstract

IMPORTANCE

The dementia syndrome of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) can be caused by 1 of several neuropathologic entities, including forms of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) or Alzheimer disease (AD). Although episodic memory is initially spared in this syndrome, the subtle learning and memory features of PPA and their neuropathologic associations have not been characterized.

OBJECTIVE

To detect subtle memory differences on the basis of autopsy-confirmed neuropathologic diagnoses in PPA.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Retrospective analysis was conducted at the Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center in August 2015 using clinical and postmortem autopsy data that had been collected between August 1983 and June 2012. Thirteen patients who had the primary clinical diagnosis of PPA and an autopsy-confirmed diagnosis of either AD (PPA-AD) or a tau variant of FTLD (PPA-FTLD) and 6 patients who had the clinical diagnosis of amnestic dementia and autopsy-confirmed AD (AMN-AD) were included.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Scores on the effortless learning, delayed retrieval, and retention conditions of the Three Words Three Shapes test, a specialized measure of verbal and nonverbal episodic memory.

RESULTS

The PPA-FTLD (n = 6), PPA-AD (n = 7), and AMN-AD (n = 6) groups did not differ by demographic composition (all P > .05). The sample mean (SD) age was 64.1 (10.3) years at symptom onset and 67.9 (9.9) years at Three Words Three Shapes test administration. The PPA-FTLD group had normal (ie, near-ceiling) scores on all verbal and nonverbal test conditions. Both the PPA-AD and AMN-AD groups had deficits in verbal effortless learning (mean [SD] number of errors, 9.9 [4.6] and 14.2 [2.0], respectively) and verbal delayed retrieval (mean [SD] number of errors, 6.1 [5.9] and 12.0 [4.4], respectively). The AMN-AD group had additional deficits in nonverbal effortless learning (mean [SD] number of errors, 10.3 [4.0]) and verbal retention (mean [SD] number of errors, 8.33 [5.2]), which were not observed in the PPA-FTLD or PPA-AD groups (all P < .005).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

This study identified neuropathologic associations of learning and memory in autopsy-confirmed cases of PPA. Among patients with clinical PPA syndrome, AD neuropathology appeared to interfere with effortless learning and delayed retrieval of verbal information, whereas FTLD-tau pathology did not. The results provide directions for future research on the interactions between limbic and language networks.

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by prominent language deterioration and early preservation of other cognitive abilities.1–3 Neuropathologically, PPA can be caused either by a variant of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), usually either FTLD with TAR DNA-binding protein 43 proteinopathy or FTLD with tau proteinopathy (FTLD-tau), or by an atypical form of Alzheimer disease (AD) that initially spares episodic memory.4–6 More rarely, the syndrome has been associated with other neuropathologic entities, like Lewy body disease and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.7

Over the past decade, researchers have characterized neuroanatomic and neuropathologic associations of language impairment in patients with PPA.2 For example, agrammatic symptoms have been associated with left posterior frontoinsular damage and FTLD-tau neuropathology, whereas logopenic symptoms have been linked to left posterior perisylvian or parietal damage and AD neuropathology.8 The discovery of these language variants has advanced the understanding of PPA and the neuroanatomic networks underlying language.9,10 Characterizing neuropathologic associations of more subtle types of dysfunction that occur in patients with PPA may provide further clinical and scientific insights.

Episodic memory is not a hallmark of the PPA syndrome, and its presence early in the course of disease is an exclusionary criterion for the diagnosis. The present study examined whether episodic memory features vary according to the nature of underlying neuropathology in patients with PPA. Using a specialized instrument, the Three Words Three Shapes (3W3S) test, we compared subtle aspects of verbal and nonverbal learning, delayed retrieval, and retention.11 In a prior clinical study12 of the 3W3S test, effortless (but not effortful) learning and delayed retrieval (but not retention) of verbal information were affected in patients with a clinical diagnosis of PPA, whereas aspects of effortful learning and retention of both verbal and nonverbal information were affected in patients with a clinical diagnosis of amnestic dementia. We hypothesized that the effortless learning, delayed retrieval, and retention portions of the3W3Stest could differentiate among patients with these forms of clinical dementia on the basis of their primary autopsy diagnoses, given that FTLD and AD neuropathologies are shown to have different predilection patterns, the latter having preference for the hippocampal memory network.4,5,13

Methods

Sample

This study was a retrospective analysis of data from 19 patients with dementia who were enrolled in National Institute on Aging–funded Alzheimer Disease Center programs. All patients underwent clinical evaluations and subsequent brain autopsies between 1983 and 2012. Fifteen patients were evaluated at the Northwestern Alzheimer Disease Center and 4 were part of an archival cohort followed up by 2 of the authors (S.W. and M.M.M.) at the Massachusetts Alzheimer Disease Center. Research was approved by the institutional review boards at the Northwestern and Massachusetts Alzheimer Disease Centers. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in a longitudinal research project and written commitment to brain donation and autopsy on death.

Clinical subtypes were determined based on retrospective medical record review and in accordance with current research diagnostic criteria.2,14 For neuropathologic diagnoses, standard histologic and immunohistochemical methods were used to identify hyperphosphorylated tau, hyperphosphorylated TAR DNA-binding protein 43, and nucleoporin p62 inclusions that characterize patients with FTLD15 and to identify neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid-containing plaques that characterize patients with AD.16–18 Of 13 patients clinically diagnosed as having PPA, 6 were diagnosed at autopsy with FTLD (PPA-FTLD) and 7 were diagnosed at autopsy with AD (PPA-AD). As it turned out, all patients with PPA-FTLD had tau pathology and the agrammatic variant of PPA. In the PPA-AD group, 1 patient was diagnosed as having agrammatic PPA and 6 as having logopenic PPA. An additional 6 patients were clinically diagnosed with amnestic dementia and with AD (AMNAD) at autopsy.

3W3S Test

The 3W3S test is a specialized measure of learning and memory for both verbal items (printed words) and nonverbal items (simple geometric shapes).11 Using the test, verbal memory can be directly compared with nonverbal memory without confounding modality of presentation, allowing for the identification of language-based deficits and their influence on performance. The amount of material to be learned remains within most individuals’ normal immediate span of attention,19 so the failure to learn is unlikely owing to reduced attention or working memory span, which can be affected in the logopenic subtype of PPA.20–22 Further, the test was designed to minimize the influence of language comprehension and output on performance. Aside from the verbal components (printed words), the test contains few requirements for normal language. For example, the procedure occurs entirely within the visual modality and has brief, straightforward instructions that do not penalize language comprehension deficits. These features distinguish the 3W3S test from many standard memory tests, which rely heavily on the use of language and therefore may yield the erroneous impression of episodic memory deficits in cases of aphasia.23

The 3W3S test assesses learning and memory over 5 conditions: copy, incidental recall (effortless learning), acquisition (effortful learning), delayed recall, and recognition, as previously described.12 In the copy condition, the patient is asked to copy 3 geometric designs and 3 words printed directly beneath each design on a page. The purpose of this condition is to ensure that perceptuomotor abilities are adequate for completion of the remaining conditions and to reinforce attention to the test items.23

The 3W3S test assesses 2 distinct aspects of learning. Immediately following the copy section is the incidental recall condition, in which the patient is given a blank page and instructed to reproduce the 6 items from memory. This novel condition provides a measure of effortless learning that occurs without conscious attention or effort to learn because the patient is not forewarned to remember the stimuli during or after copying them. In the subsequent acquisition phase, the patient is given 30 seconds to study the words and shapes and then immediately reproduce them from memory on a blank page; this condition ends when at least 5 items are correctly produced or after 5 study trials. The reproduction at the final study trial is used to derive the acquisition score, which represents effortful learning, or the amount of information learned at that point.

The 3W3S test also assesses 2 distinct aspects of delayed memory. In the delayed recall condition, the patient is instructed to reproduce the words and shapes from memory after some time has passed, which provides a measure of spontaneous retrieval. In the final recognition condition, the patient is asked to identify the 3 words and 3 shapes from among 14 distractors, which provides a measure of retention.

Patients received the 3W3S test as part of a clinical neurology evaluation, so the time interval from acquisition to delayed recall varied across the sample. However, the delay interval was treated similarly for all cases because prior research11 on the 3W3S test in patients with amnestic dementia demonstrated that the greatest loss of information occurred after 5 minutes, and longer intervals did not reveal significantly more loss. Further, the delay interval did not significantly differ across the 3 groups; the mean (SD) was 10.0 (7.7) minutes in the PPA-FTLD group, 8.6 (4.8) minutes in the PPA-AD group, and 8.8 (6.2) minutes in the AMN-AD group (P = .91).

Words and shapes were evaluated for accuracy and placement using scoring criteria that have been described previously.11 Every condition received a word and shape score from 0 to 15 points, where 15 indicated an error-free performance. Full credit was given for recognition scores in cases where delayed recall scores were perfect. All patients in the present study were required to score within 1.5 SDs of the mean taken from previously published elderly controls12 on the copy and word acquisition conditions to equate initial encoding.

Assessment of Clinical Severity

Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, patients differed in the amount and type of clinical and neuropsychological assessments available from the time of 3W3S test administration. Fourteen of 19 patients (73.7%) received the Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (ADLQ),24 an informant-rated survey of functional impairments, at the time of the 3W3S test; the others were given a qualitative rating based on consensus medical record review of information available from the time of testing. Functional impairment was used to estimate disease severity in the present study because in a longitudinal study25 of patients with PPA, ADLQ scores declined far less dramatically than did Mini-Mental State Examination scores, suggesting that the true level of clinical severity in PPA may be overestimated by the Mini-Mental State Examination or other assessments that contain a high proportion of verbal items. On the ADLQ, functional impairment is rated as none to mild (0%–33%), moderate (34%–66%), or severe (67%–100%).24 All patients received either the full or 15-item version of the Boston Naming Test (BNT) at the time of 3W3S testing.26,27 The BNT percentage correct score was used to classify naming as normal (above 80%),mildly impaired (60%–80%), or severely impaired (below 60%).

Statistical Analyses

First, the groups’ clinical variables were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kruskal-Wallis procedures. Then, the 3 groups’ mean word and shape scores in the incidental recall, delayed recall, and recognition conditions were compared using ANOVA with a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level to correct for multiple comparisons (P < .008). In cases where the 3 groups differed significantly from one another, post hoc t tests were used to identify significant pairwise differences.

Within-group differences in effortless learning (copy vs incidental recall), delayed retrieval (acquisition vs delayed recall), and retention (recognition vs delayed recall) were tested using ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections (P < .025). Within-group material-specific differences in each condition (words vs shapes) were also examined using ANOVA with Bonferroni correction (P < .01), given that disproportionate verbal memory problems have been reported in clinical studies of PPA.12,28

Results

Clinical and Neuropathologic Characteristics

The 3 groups did not differ significantly from one another in any of the features shown in the Table (all P > .05). For all patients, the mean (SD) age was 64.1 (10.3) years at symptom onset and 67.9 (9.9) years at the time of the 3W3S administration. Seventeen of 19 patients (89.5%) were rated as having mild disease at the time of the 3W3S test; the mean (SD) ALDQ score was 27.5 (4.2). Two patients with AMN-AD were rated as moderate, with ADLQ scores of 45 and 59, but Mini-Mental State Examination scores of 24 of 30 and 26 of 30, respectively. The sample mean (SD) percentage on the BNT was 72.0 (26.6), indicating an overall mild naming impairment at the time of the 3W3S test. Eight patients demonstrated a significant naming impairment on the BNT. Of note, these 8 patients all obtained perfect word acquisition scores, suggesting that even those with the most severe naming deficits were capable of learning and producing the words on the 3W3S test.

Table.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Group

| Characteristic | PPA-FTLD (n = 6) |

PPA-AD (n = 7) |

AMN-AD (n = 6) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | ||||

| Onset of symptoms | 60.3 (9.5) | 69.0 (10.3) | 62.2 (10.5) | .29 |

| Clinical evaluation | 63.2 (10.0) | 72.6 (9.7) | 67.3 (9.1) | .24 |

| Death | 71.2 (7.5) | 79.1 (5.0) | 73.8 (8.9) | .16 |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 16.0 (2.8) | 15.4 (2.8) | 14.0 (3.3) | .50 |

| Sex, No. | ||||

| Male | 4 | 5 | 4 | .98 |

| Female | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA |

| Clinical severity rating, No. | ||||

| Mild impairment | 6 | 7 | 4 | .09 |

| Moderate impairment | 0 | 0 | 2 | NA |

| Object naming, BNT % correct, mean (SD) |

90.6 (14.2) | 56.9 (24.8) | 71.1 (29.7) | .07 |

| Braak stage, No. | ||||

| 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 6 | 0 | 5 | 4a | NA |

| CERAD plaque density ratings, No. | ||||

| None | 4 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Mild | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Frequent | 1 | 7 | 4a | NA |

Abbreviations: AD, autopsy diagnosis of Alzheimer disease neuropathology; AMN, clinical diagnosis of amnestic dementia; BNT, Boston Naming Test; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; FTLD, autopsy diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration; NA, not applicable; PPA, clinical diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia.

Although these patients had been given neuropathologic diagnoses of Alzheimer disease, Braak staging and CERAD ratings were not available.

The interval between 3W3S test administration and death did not significantly differ across the 3 groups; the mean (SD) age was 8.0 (3.6) years in the PPA-FTLD group, 6.6 (5.4) years in the PPA-AD group, and 6.7 (1.2) years in the AMN-AD group (P = .78). All patients with PPA-FTLD in the sample were diagnosed with a variant of tau pathology: 2 were diagnosed as having corticobasal degeneration, 1 as having progressive supranuclear palsy, and 3 as having Pick disease. The Table includes Braak neurofibrillary stages and Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease plaque densities, which were available within each group. None of the patients showed evidence of Lewy-type synuclein pathology. Additional details on the clinical and neuropathologic features of all 13 patients with PPA were reported in 2 prior autopsy studies,4,5 and additional details on 4 of the patients with PPA-AD and 3 with AMN-AD were reported in an additional autopsy study.29

3W3S Test Performance

Effortless Learning

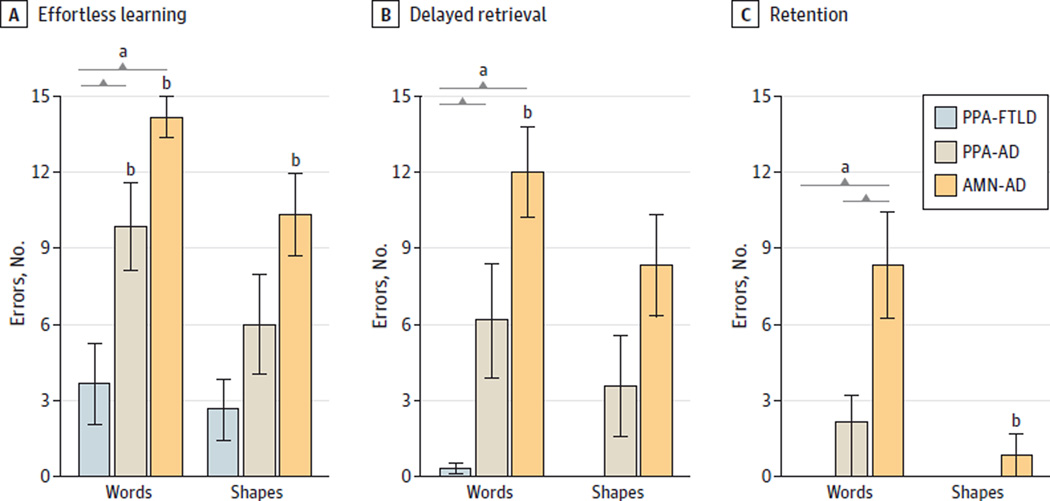

The mean (SD) number of incidental recall errors for the PPA-FTLD, PPA-AD, and AMN-AD groups was 3.7 (3.8), 9.9(4.6), and 14.2 (2.0) for words and 2.7 (2.9), 6.0 (5.2), and 10.3 (4.0) for shapes, respectively. The 3 groups differed significantly from one another in the incidental recall of words (P = .001) but not shapes (P = .02; Bonferroni-adjusted P < .008) (Figure, A). This difference was a function of neuropathologic, rather than clinical, diagnosis. Post hoc comparisons showed that the PPA-FTLD group made significantly fewer incidental recall word errors than both the PPA-AD (P = .02) and AMN-AD (P = .001) groups, whereas the PPA-AD and AMN-AD groups did not differ from each other (P = .06).

Figure. Effortless Learning, Delayed Retrieval, and Retention Performance by Group.

Colored bars represent the mean number of errors in the (A) incidental recall, (B) delayed recall, and (C) recognition conditions of the Three Words Three Shapes test for the 3 diagnostic groups. Brackets indicate significant pairwise differences. Error bars indicate 1 SD; error bars are absent for groups that had perfect (ie, error-free) performances. AD indicates autopsy diagnosis of Alzheimer disease neuropathology; AMN, clinical diagnosis of amnestic dementia; FTLD, autopsy diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration; PPA, clinical diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia.

a Significant difference across the 3 groups (P = .001).

b Significant within-group difference (P < .025).

To identify within-group differences in effortless learning, incidental recall was compared with the copy condition in each group. The PPA-FTLD group demonstrated a high capacity for effortless learning, as incidental recall did not differ from copy of words (P = .06) or shapes (P = .08). The PPA-AD group made significantly more errors in incidental recall than in the copy of words (P = .001) but not shapes (P = .03; Bonferroni-adjusted P < .025). The AMN-AD group made significantly more errors in incidental recall than in the copy of both words and shapes (both P = .001).

Delayed Retrieval

The mean (SD) number of delayed recall errors for the PPA-FTLD, PPA-AD, andAMN-ADgroupswas0.3 (0.5), 6.1 (6.0), and 12.0(4.4) for words and 0 (0), 3.6 (5.3), and 8.3 (4.9) for shapes, respectively. The 3 groups differed significantly from one another in the delayed recall of words (P = .001) but not shapes (P = .01; Bonferroni-adjusted P < .008) (Figure, B). This difference was also a function of neuropathologic, rather than clinical, diagnosis. Post hoc comparisons showed that the PPA-FTLD group made significantly fewer errors than both the PPA-AD (P = .04) and AMN-AD (P = .001) groups and, whereas the PPA-AD and AMN-AD groups did not differ from each other (P = .07).

To identify within-group differences in the capacity for retrieval of previously learned material, delayed recall was compared with acquisition in each group. The PPA-FTLD group demonstrated a high retrieval capacity, as delayed recall did not differ from acquisition of words (P = .18) or shapes (P = .99). The PPA-AD group tended to make more errors in delayed recall than in acquisition of words, but differences did not reach statistical significance for words (P = .03; Bonferroni-adjusted P < .025) or shapes (P = .20). The AMN-AD group made significantly more errors in delayed recall than in acquisition of words (P = .003) but not shapes (P = .31).

Retention

The mean (SD) number of recognition errors for the PPA-FTLD, PPA-AD, and AMN-AD groups was 0 (0), 2.1 (2.7), and 8.3 (5.2) for words and 0 (0), 0 (0), and 8.3 (2.0) for shapes, respectively. The 3 groups differed significantly from one another in the recognition of words (P = .001) but not shapes (P = .36) (Figure, C). This difference was a function of clinical, rather than neuropathologic, diagnosis. Post hoc comparisons showed that the AMN-AD group made significantly more word recognition errors than both the PPA-FTLD (P = .01) and PPA-AD (P = .02) groups, whereas the PPA-FTLD and PPA-AD groups did not differ from each other (P = .08).

To identify within-group differences in retention, recognition was compared with delayed recall in each group. Scores did not significantly differ within the PPA-FTLD group (both P > .10). The PPA-AD group tended to make fewer errors in recognition than in delayed recall of words, but differences did not reach statistical significance for words (P = .03;Bonferroni-adjusted P < .025) or shapes (P = .13). The AMN-AD group made significantly fewer errors in recognition than in delayed recall of shapes (P = .01) but not words (P = .07), suggesting that verbal retention was reduced (in addition to the poor retrieval) in this group.

Material Specificity

No significant within-group differences between word and shape scores were observed in the copy, incidental recall, acquisition, delayed recall, or recognition conditions (all P > .01). This finding is inconsistent with the results of clinical studies that report verbal (but not nonverbal) memory deficits in patients with PPA.11,28 The lack of material specificity may be driven by the small sample size and low statistical power of the present study, given that both PPA groups tended to make more word than shape errors overall. In the PPA-AD group, the discrepancy between word and shape scores in the incidental recall condition showed a trend toward significance (P = .05). Furthermore, the 3W3S test is delivered entirely in the visual modality, whereas standard verbal memory tests typically occur in the auditory modality while nonverbal memory is tested through drawing.

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify differences in episodic memory performance as a function of neuropathologic and clinical diagnoses in an autopsy-confirmed series of patients with dementia. The instrument that we used, the 3W3S test, was designed to identify differences in verbal and nonverbal learning and memory within each diagnostic group.

As hypothesized, performance on portions of the 3W3S test that measure effortless learning, delayed retrieval, and retention distinguished among the 3 diagnostic groups of similar demographic composition and clinical severity. Patients with PPA due to FTLD (entirely tau-related in this series) performed near-ceiling on all conditions of the 3W3S test. In fact, their scores were statistically indistinguishable from the scores of elderly control subjects reported in a prior study (all P > .10).12 In contrast, patients with amnestic dementia and those with PPA due to Alzheimer pathology demonstrated verbal effortless learning and retrieval deficits. Those with clinically amnestic dementia also showed a deficit in nonverbal effortless learning, which was not observed in either PPA group. Retention, the aspect of learning and memory most closely linked to episodic memory and its limbic substrate,30 was impaired only in the AMN-AD group.

In most cases, Alzheimer pathology selectively accumulates in medial temporal regions critical for memory, leading to an initially primary amnestic syndrome.30 In other cases, Alzheimer pathology displays an atypical prominence of neurofibrillary degeneration in components of the language network, leading to the syndrome of PPA.6,7 However, even these cases have substantial limbic neurofibrillary degeneration,13 which could explain the subtle but definite memory impairments we observed. Future research on the association of these deficits to the distribution of pathology could provide valuable information on interactions between limbic and language networks.

Our findings provide support for the 3W3S test as a practical and informative test of episodic memory in patients with dementia. It is brief and easy to administer and interpret in outpatient clinical settings. In patients with suspected PPA, the 3W3S test may actually prove more useful than standard memory tests, given that it was designed to minimize extraneous language demands and to compare subtle verbal and nonverbal features of memory. The materials are available at no cost via the Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer Disease Center at http://www.brain.northwestern.edu/research/for-researchers/3W3S.html.

Limitations of the present study must be addressed. Namely, the small sample size may have limited the power to detect some differences, like material specificity, previously reported instudies of memory in patients with PPA.12,28 Further, the availability of data was limited by the retrospective nature of the study. Detailed clinical and neuropsychological data were not uniformly collected from all patients at the time of the 3W3S test administration. Six patients did not have a formal ADLQ rating available, so clinical severity had to be qualitatively rated based on medical record review of historical information.

Conclusions

The present study helped to characterize differential patterns of verbal and nonverbal learning and memory in relation to neuropathology in autopsy-confirmed cases of PPA. Our findings are consistent with our previous study12 and other reports28 that retentive memory is largely preserved in all cases of clinical PPA. However, our study also shows that patients with PPA with Alzheimer pathology have selective vulnerabilities in effortless learning and delayed retrieval of verbal information, whereas patients with PPA–FTLD-tau neuropathology do not.

Key Points.

Question

Do episodic memory features vary based on the nature of the underlying neuropathology in primary progressive aphasia (PPA)?

Findings

In this analysis of clinical and autopsy data of 19 patients, patients with amnestic dementia and patients with PPA with Alzheimer neuropathology had significantly worse effortless learning and delayed retrieval of verbal information than patients with PPA with frontotemporal lobar degeneration–tau pathology. Patients with amnesia also had significantly worse nonverbal effortless learning and verbal retention than all patients with PPA, regardless of pathology.

Meaning

These results help to characterize differential patterns of verbal and nonverbal episodic memory based on autopsy-confirmed neuropathology in PPA and provide directions for future research on the interactions between limbic and language networks.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant DC008552 from National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders and grant AG13854 (Alzheimer Disease Core Center) from the National Institute on Aging.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had a role in the design and conduct of the study and the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data but not in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Weintraub is funded by grants R01DC008552, P30AG013854, and R01NS075075 from the National Institutes of Health and the Ken and Ruth Davee Foundation and conducts clinical neuropsychological evaluations (35%effort), for which her academic-based practice clinic bills. She serves on the editorial board of Dementia and Neuropsychologia and advisory boards of the Turkish Journal of Neurology and Alzheimer’s and Dementia. Dr Rogalski is funded by grants R01DC008552, R01NS075075, R01 AG045571, and R03 DC013386 from the National Institutes of Health and receives grant support from the Ken and Ruth Davee Foundation and the Alzheimer’s Association. Drs Bigio, Rademaker, and Mesulam are supported by grant P30AG13854 from the National Institutes of Health. Dr Bigio is on the editorial boards of the Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology and Brain Pathology. Ms Kielb is funded by grant T32 AG020506 from the National Institutes of Health. Ms Cook is funded by grant T32NS047987 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Ms Kielb had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kielb, Cook, Rademaker, Mesulam, Rogalski, Weintraub.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Kielb, Cook, Rademaker, Bigio, Mesulam, Rogalski, Weintraub.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kielb, Wieneke, Bigio, Mesulam, Rogalski, Weintraub.

Statistical analysis: Kielb, Rademaker.

Obtained funding: Mesulam, Rogalski.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Cook, Wieneke.

Study supervision: Bigio, Mesulam, Rogalski, Weintraub.

Additional Contributions: We thank Emily Shaw, BA (Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston), for technical assistance with data collection. Ms Shaw was not compensated for her contribution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesulam M, Weintraub S. Primary progressive aphasia and kindred disorders. In: Duyckaerts C, Litvan I, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 573–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesulam M, Wicklund A, Johnson N, et al. Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(6):709–719. doi: 10.1002/ana.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, Bigio EH. Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2014;137(pt 4):1176–1192. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alladi S, Xuereb J, Bak T, et al. Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130(pt 10):2636–2645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris JM, Gall C, Thompson JC, et al. Classification and pathology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2013;81(21):1832–1839. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436070.28137.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesulam M, Wieneke C, Rogalski E, Cobia D, Thompson C, Weintraub S. Quantitative template for subtyping primary progressive aphasia. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(12):1545–1551. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mesulam MM, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(10):554–569. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesulam MM, Thompson CK, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ. The Wernicke conundrum and the anatomy of language comprehension in primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2015;138(pt 8):2423–2437. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weintraub S, Peavy GM, O’Connor M, et al. Three Words Three Shapes: a clinical test of memory. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000;22(2):267–278. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200004)22:2;1-1;FT267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weintraub S, Rogalski E, Shaw E, et al. Verbal and nonverbal memory in primary progressive aphasia: the Three Words-Three Shapes Test. Behav Neurol. 2013;26(1–2):67–76. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2012-110239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gefen T, Gasho K, Rademaker A, et al. Clinically concordant variations of Alzheimer pathology in aphasic versus amnestic dementia. Brain. 2012;135(pt 5):1554–1565. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bigio EH. Making the diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(3):314–325. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0075-RA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging: Alzheimer’s Association. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD): part II. standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller GA. The magical number seven plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol Rev. 1956;63(2):81–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foxe DG, Irish M, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Verbal and visuospatial span in logopenic progressive aphasia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013;19(3):247–253. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer AM, Snider SF, Campbell RE, Friedman RB. Phonological short-term memory in logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 2015;71:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tree J, Kay J. Longitudinal assessment of short-term memory deterioration in a logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia with post-mortem confirmed Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Neuropsychol. 2015;9(2):184–202. doi: 10.1111/jnp.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weintraub S, Mesulam M-M. Mental state assessment of young and elderly adults in behavioral neurology. In: Mesulam M-M, editor. Principles of Behavioral Neurology. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 1985. pp. 71–123. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson N, Barion A, Rademaker A, Rehkemper G, Weintraub S. The Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire: a validation study in patients with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(4):223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osher JE, Wicklund AH, Rademaker A, Johnson N, Weintraub S. The mini-mental state examination in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22(6):468–473. doi: 10.1177/1533317507307173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fastenau PS, Denburg NL, Mauer BA. Parallel short forms for the Boston Naming Test: psychometric properties and norms for older adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(6):828–834. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.6.828.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zakzanis KK. The neuropsychological signature of primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 1999;70(1):70–85. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bigio EH, Mishra M, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. TDP-43 pathology in primary progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia with pathologic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(1):43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markowitsch HJ. Memory and amnesia. In: Mesulam M-M, editor. Principles of Behavioral Neurology. 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 257–283. [Google Scholar]