Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a chemical hazard in the gas and farming industry. As it is easy to manufacture from common chemicals, it has also become a method of suicide. H2S exerts its toxicity through its high affinity with metallo-proteins, such as cytochrome c oxidase and possibly via its interactions with cysteine residues of various proteins. The latter was recently proposed to acutely alter ion channels with critical implications for cardiac and brain functions. Indeed, during severe H2S intoxication, a coma, associated with a reduction in cardiac contractility, develops within minutes or even seconds leading to death by complete electro-mechanical dissociation of the heart. In addition, long-term neurological deficits can develop due to the direct toxicity of H2S on neurons combined with the consequences of a prolonged apnea and circulatory failure. Here, we review the challenges impeding efforts to offer an effective treatment against H2S intoxication using agents that trap free H2S, and present novel pharmacological approaches aimed at correcting some of the most negative consequences of H2S intoxication.

Keywords: H2S, pulseless electrical activity, apnea, hydroxocobalamin, methemoglobin, methylene blue, hydrogen sulfide

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) remains a significant chemical hazard 1, 2 in gas and oil industry 3–6, and in various farming 7 as well as fishing activities 8. It is also used as a method of suicide 9. This form of suicide 10 is accomplished by mixing, in a closed environment, a source of sulfide and various types of acidic solutions, which are readily available in most household chemicals 11, 12.

The consequences of an acute exposure to H2S are usually benign as long as the level of exposure remains in the low ppm ranges, but as soon as exposure reaches levels above 500 ppm, the toxicity of H2S towards the heart and the central nervous system can lead to rapid death or produce dreadful long-term neurological deficits 4. Acute toxicity in surviving patients is associated with lesions of the olfactory epithelium, 13 as well as pulmonary lesions, 14 leading to a clinical picture of acute respiratory failure often requiring mechanical ventilation.

In this short review we will present some of the specificities of H2S poisoning that, in our view, represent a major challenge when developing antidotes or countermeasures. Indeed, one of the major factor impeding our effort to come up with an effective treatment against H2S intoxication after exposure is that the pool of free/soluble H2S disappears from the body as soon as the exposure ceases 15, 16, preventing agents trapping free H2S (cobalt or ferric compounds) to play their protective role. Yet, H2S still exerts its toxicity well beyond the phase of exposure through mechanisms, which are not yet fully understood, but are not related to the persistence of free H2S 15, 16. After a very brief presentation of our current understanding of H2S metabolism, we will discuss some of the most recent results on the efficacy and limits of trapping agents and propose a new paradigm to treat some of the most dramatic complications of acute H2S intoxication.

Acute H2S intoxication: short- and long-term effects

H2S toxicity–dose relationship is extremely steep and life-threatening symptoms can be produced by inhaling no more than 0.07% H2S for as little as a few minutes. Figure 1 and 2 illustrates how relatively small increases in the level of exposure to infused H2S can advance symptoms from a stimulation of breathing, to an apnea, and finally to a very rapid cardiac arrest, for blood concentrations of H2S of a similar order of magnitude (Fig. 2).

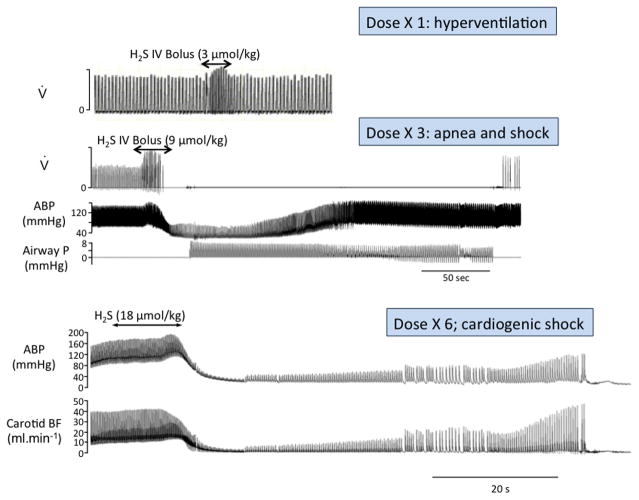

Figure 1.

Recordings in three urethane anesthetized rats showing the effects on breathing (inspiratory flow, V), blood pressure (ABP) and carotid blood flow (BF) of a bolus injection of a solution containing H2S at three different concentrations. The first observable symptom in this model was produced at a concentration of about 3 μmol/kg and consisted in a transient increase in breathing secondary to the stimulation of the arterial chemoreceptors. At 9 μmol/kg, animals would display a central apnea and a severe hypotension. In this example, death was prevented by initiating mechanical ventilation, as illustrated by the changes in airway pressure (airway P), allowing spontaneous breathing to resume and circulation to return to its baseline levels after several minutes. Doubling this dose provoked an immediate and irreversible shock leading to a rapid asystole, regardless of the ventilatory support. Modified from Ref. 77.

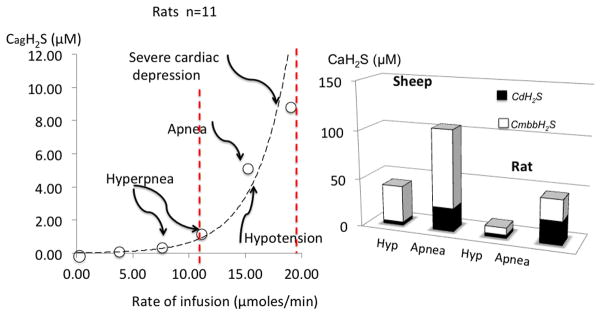

Figure 2.

Relationship between the estimated concentrations of gaseous H2S (soluble) and the rate of H2S infused in rats. CgH2S refers to the concentration of gaseous form of H2S, while CDH2S is the form combining CgH2S and the concentration in HS–. CmmbH2S represents the concentration the total pool of H2S present in the blood determined by the monobromobimane (MBB) method. Modified from Refs. 15 and 16). Note that breathing was stimulated at concentrations of CgH2S around or even below 1 μM in the blood, while lethal concentrations are about 8 μM only. Left panel shows the comparison between rats and large animals (sheep). Note that symptoms are produced in both species at similar levels of soluble gaseous in the blood. Sheep seem to have a higher pool of total H2S than rats.

During intoxication in humans and in un-sedated animals, acute exposure to H2S provokes a rapid coma 3, 17. H2S-induced coma is often referred to as knock-down, a term coined to illustrate the spontaneous and rapid reversibility of the coma if the exposure is of short duration. Knock-down is, however, far from benign, as it can be fatal 18 within minutes whenever concomitant acute cardiogenic shock develops 19. Our experience in rats and sheep exposed to toxic levels of H2S shows there is a very fine line between a benign form of intoxication and a lethal one.

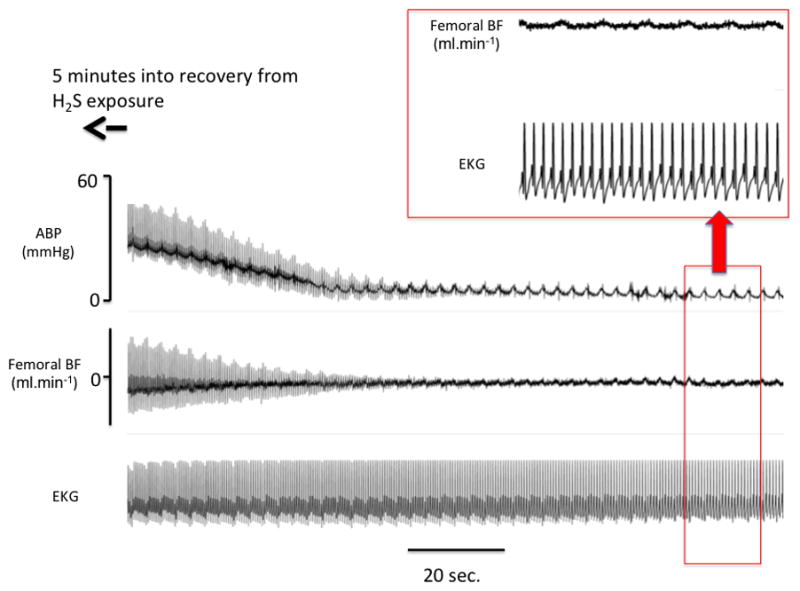

Death due to H2S poisoning is secondary to a pulseless electrical activity (PEA) i.e. cardiac contractions are abolished while rhythmic electrical activity persists 19–22, which can very rapidly develop, as an endpoint of a primary depression in cardiac contractility. We found that ventricular fibrillation occurs more rarely than PEA. We also found that an isolated apnea, i.e. without any primary cardiac failure, can only be observed in a very narrow range of H2S exposures, which can be uniquely created in the artificial setting of an experimental protocol. Indeed, although apnea induced anoxia can precipitate the development of a PEA and may contribute to brain ischemic/hypoxic injury 23, the blood concentrations of H2S able to reduce breathing already provokes a significant alteration in the cardiac function15–62 (Fig. 2). Consequently, for all intents and purposes the presence of a depression in breathing should always be seen as a marker of a severe primary depression in cardiac function. The basis for these contentions was described in the following studies18–22. Note that in all the following experiments, H2S was prepared from NaHS, dissolved in saline. The term “H2S solution” will be used instead of “NaHS” throughout the manuscript for clarity. In one of these studies, using the relationship we previously established between H2S concentrations and circulation20, we studied the effects of H2S at a rate of infusion (10 μM/min) that would be lethal in 10 minutes in rats (n = 14) anesthetized by urethane (1.2 mg/kg, IP) and mechanically ventilated. Arterial blood pressure and left ventricular pressures were monitored using PE-50 catheters. Transonic flow probes (MA2PSB) were placed around the ascending aorta, following median sternotomy, and around one femoral artery to measure cardiac output and femoral blood flow respectively (Fig. 4). We found that H2S dramatically depresses cardiac systolic function, within less than one minute of exposure, resulting in a cardiogenic shock leading to PEA within 5 to 7 minutes (Fig. 4). Similar cardiac effects were found in a study involving sixteen sheep22. Of note, PEA can develop even after the end of exposure (Fig. 5). In non-sedated animals that are breathing spontaneously, minute ventilation is also depressed through a centrally inhibition of the medullary respiratory neurons, but the period of apnea is replaced by a gasping pattern18 that can be maintained for long periods of time. This gasping pattern allows auto-resuscitation to occur, if circulation is maintained or restored18. As mentioned earlier, in less dramatic intoxications, the clinical manifestations consist in a syncopal episode and a persistent period of hypotension23. Long-term cognitive or motor deficits can still develop. These Deficits have been shown to take place in animal models 18 and in humans 24. We found that in a model of intoxication leading to a 75% mortality, 25% of surviving animals had neurological lesions18, which included diffuse neuronal necrosis of the cortex, putamen, and thalamus. The hippocampus and the cerebellum were spared, in contrast to what is typically seen in post-anoxic injury. This description suggests that although neuronal necrosis could be facilitated by the ischemic insult secondary to severe circulatory depression and hypoventilation induced hypoxemia23, H2S seems to produce genuine neuronal lesions, different from those produced by anoxia18. Finally, acute lesions of the olfactory epithelium13, 25 and the lungs26 are present during a single exposure to inhaled H2S starting from 400 ppm.

Figure 4.

Example of the effects of exposure to a lethal level of H2S in one sheep. Recording is shown starting five minutes after the end of exposure. APB: arterial blood pressure; BF blood flow. Note that a picture of complete pulseless electrical activity or electromechanical dissociation occurred well after the end of exposure, i.e. at a time when free H2S was undetectable in the blood or the expiratory gas.

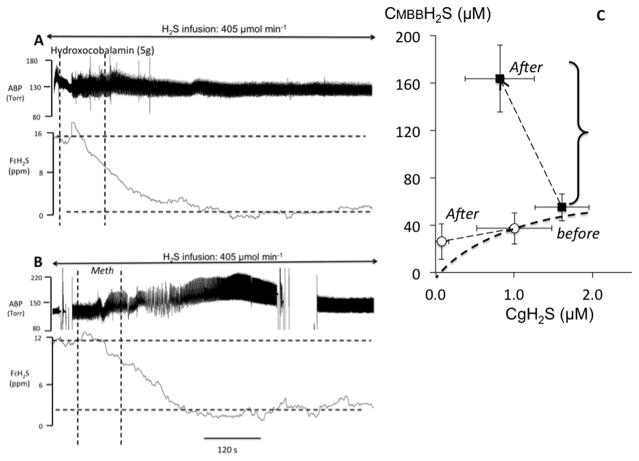

Figure 5.

A. Recording obtained in one sheep during a continuous infusion of H2S solution at a rate of 405 μmol/min. APB: arterial blood pressure; FEH2S: expired fraction of H2S. The dashed vertical lines indicate the start and end of hydroxocobablamin (HyCo) injection (5 g in saline solution). The gaseous form of H2S in the blood decreased dramatically during HyCo infusion reaching almost zero despite the persistence of sulfide infusion. B. Recording in one sheep during a continuous infusion of NaHS at the same rate of 405 μmol/min, receiving an infusion of Methemoglobine (MetHb) solution (600 mg of human-derived Hb (Sigma Aldrich) in sterile saline (200 mg/mL)). Expired H2S decreased dramatically during MetHb infusion and continued to decrease beyond the period of MetHb infusion. C. relationship between the mean±SD concentrations of gaseous H2S (CgH2S) and total H2S (CMBBH2S), before and after MetHb infusion (black symbols) and HyCo infusion (open symbols). CgH2S significantly decreased following MetHb infusion with a four-fold increase in CMBBH2S reflecting the increased level of H2S combined on MetHb. The decrease in CgH2S was even more significant following HyCo infusion with no increase in CMBBH2S, suggesting that H2S oxidation may have been catalysed in the presence of the cobalt compound. Clearly although these two metallo-compounds do not have the same effect on the pools of combined H2S, they both can decrease soluble H2S very efficiently. Modified from Refs. 16 and 52.

The mechanisms of H2S toxicity remain debated

The toxicity of H2S has long been considered to result from its combination with the ferric heme a3 of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase27, inhibiting its activity28, 29, in turn preventing ATP formation and promoting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)30. However, recent works on the interaction between H2S and proteins31, including ion channels32, suggest that H2S could affect cysteine residues of most proteins by direct “sulfhydration” or “sulfuration” of free cysteine residues (S-SH bonds)33. This mechanism has been put forward to account for the extreme and early cardiac toxicity of H2S on Ca2+ channels32, 34, including on the sarcoplasmic reticulum ryanodine receptors (RyR) rich in free cysteine residues. Due to the multitude of metallo-proteins physiologically present in the cells and in the blood (from hemoglobin in the blood to myoglobin in the heart and muscles) and the high rate of H2S oxidation, it is unclear if and how much free hydrogen sulfide could combine to cysteine residues of proteins in vivo. Alternatively, an increased ROS production––a result of the impediment of the electron chain activity 35––can also affect the activity of the calcium channels36. Regardless of the mechanisms involved, various ion channels, including K+-ATP 37 or Ca2+ 32, 34, 38 channels, can be affected by H2S in the heart and the central nervous system through mechanisms of toxicity that do not always require the mitochondrial activity to be altered, as shown for the medullary neurons39. A comprehensive description of the contribution of ion channels, “reconfiguration” of proteins, or mitochondrial dysfunction to the symptoms of sulfide poisoning is cruelly missing15, 16, 18, 19. These effects persist for a much longer time than soluble H2S in the body22 during severe intoxication and can explain the persistence of signs of toxicity even when all free H2S has vanished.

Kinetics and metabolism of free H2S, a challenge for the treatment of H2S poisoning

H2S, which is much more soluble than CO2 or O240–42, diffuses almost instantaneously into the blood as soon as it is inhaled and then to all tissues and cells. We have characterized the fate of the various pools of H2S in the blood15, their kinetics as well as their links to the clinical manifestations and symptoms of toxicity15, 16.

In the blood, only a very small portion of sulfide remains in a “free/soluble” or diffusible form, comprising the gaseous form H2S41, 43 and the sulfhydryl anion HS–. 44 A larger pool of sulfide will combine with metallo-proteins such as the ferrous iron of hemoglobin or may, as presented in the previous paragraph, react with cysteine residues present in a large number of proteins 45, creating a sink for H2S. While free/soluble H2S is the only form able to diffuse into the cells, “combined“ H2S represents the toxic pool.15, 16 A schematic representation of the fate of H2S is shown in Figure S1. The most remarkable feature of H2S metabolism is that H2S disappears spontaneously from the blood and the tissue15, 46, 47 at a very rapid rate (Fig. S2). Indeed H2S is almost immediately oxidized in the mitochondria, a reaction catalyzed by the mitochondrial sulfide quinone oxido-reductase (SQR).48 Of note, the sulfur transferase enzyme, rhodanese, has been proposed to contribute to H2S detoxification/elimination49. Thiosulfate, resulting from spontaneous oxidation of H2S, could, after reacting with one of the cysteine residues of rhodanese, create a persulfide. In the presence of cyanide, thiocaynide could then be formed. However, rhodanese, can only be involved after the conversion of H2S/HS− into thiosulfate, eventually catalyzing the conversion of thiosulfate to thiocyanate. This enzyme does not metabolize sulfide per se. As demonstrated by Wilson et al.,50 the rate-limiting step in H2S detoxification is its oxidation to thiosulfate; the conversion of thiosulfate to thiocyanate by the rhodanese does not increase the rate of sulfide detoxification. H2S also disappears spontaneously from a solution of proteins or from the blood, transformed into polysulfide, thiosulfate, sulfite, and sulfate in the presence of oxygen. We found that all these potential mechanisms of oxidation can account for the disappearance of soluble H2S, which occurs within one minute in large and small mammals15, 16 following a period of exposure to sulfide (Fig. S2), while the “hidden” forms of combined sulfide can persist for longer periods of time.51 As a consequence, the toxic effects of H2S persist beyond the phase of exposure without being accessible to an antidote that would primarily act on the free/soluble form. Only in very severe exposure that could be very rapidly lethal would H2S be unable to be oxidized at the moment of death, and thus could persist in large quantity in the body. During these extreme intoxications, no treatment could be administered on time, as death would be almost immediate. We found that in animal models, non-immediately lethal intoxications, even if severe, are associated with concentrations of H2S in blood that would be at the most in the high micromolar range. 15 At these levels, a total disappearance of H2S is to be expected as soon as the patient is removed from the source of exposure.

Therefore, the challenge is to find compounds antagonizing the effects of H2S toxicity while the pool of free or exchangeable sulfide is already gone. Yet, the treatment of H2S poisoning has been traditionally aimed at trapping free H2S using metallo-compounds, e.g. ferric iron contained in methemoglobin52–54 or cobalt in hydroxycobalamin (HyCo).54–56 Nitrite-induced methemoglobinemia57, 58 can, however, only trap H2S outside the cells and have little or no effects on the combined forms, after exposure.16 In addition, sodium nitrite can decrease arterial blood pressure in subjects already in shock and affect oxygen transport. Cobalt contained in HyCo54 has several theoretical advantages over methemoglobinemia.55, 59 Whether this very large molecule can penetrate cells at sufficient concentrations rapidly enough relies on the few data that have been gathered mostly for the study of cyanide poisoning60 and thus remains to be convincingly demonstrated. We found that HyCo (70 mg/kg) reduces the immediate mortality of sulfide in the sheep, but only when used within one or two minutes following exposure.22 In our experience, no clear beneficial effects are demonstrable if HyCo is administered later on, and more importantly HyCo does not prevent the development of a severe metabolic acidosis or lactate production in the surviving animals.22 As HyCo has no interaction with sulfide “fixed” on proteins, new paradigms must be proposed using agents counteracting the deleterious consequences of H2S toxicity, rather than trying to trap soluble H2S.

Methylene blue: a new treatment of H2S poisoning using an old molecule?

Methylene blue (MB) is a cationic tri-heterocyclic redox compound with a central aromatic thiazine ring system, for which pharmacokinetics, both in the blood and tissues, has been established in various species including humans 61, 62. MB is routinely used for the treatment of methemglobinemia at the dose of 1–2 mg/kg IV 63. MB diffuses extremely rapidly and accumulates in all tissues including the heart and the brain 62. MB has been shown to have a relatively long half-life in the blood (4–5 h in the rat) and is reduced to leucomethylene blue (LMB) in the blood and in the cells. LMB forms with MB a reversible oxidation-reduction system or electron donor-acceptor couple (see Refs. 64 and 65). In tissues, the main form of MB is LMB, which accounts for the potent reducing properties of MB. Inside cells, MB/LMB concentrates in mitochondria where it can interact with mitochondrial complexes. We have found that MB is a potent agent against H2S poisoning, when injected after the exposure, changing the immediate prognosis of severe intoxication and improving the long-term neurological outcome 18, 19. We have established that this effect is primarily related to the restoration of cardiac function, preventing PEA and restoring normal breathing 18, 19. In these experiments, rats (n = 34) received intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 20 mg/kg NaHS solution every 10 minutes until they presented a coma. On average, two injections were needed to produce a coma within 1–2 minutes; two minutes into the coma, defined as the loss of righting reflex, animals started gasping (Fig. S3). This phase led to spontaneous recovery or cardiac arrest within 7 minutes. Three minutes into the coma, the rats received either saline or MB (IV tail vein, 4 mg/kg × 2). Surviving rats underwent clinical examination, open field and Morris Water Maze (MWM) testing for 4 days starting 1 day after the intoxication. As shown in Figure S4 the immediate mortality was dramatically decreased after injection of MB (75% survival, P < 0.01). No rats were found with early neurological deficits in the MB treated group; furthermore, they displayed an effective spatial search strategy (direct, directed or focal) during MWM testing with a significantly higher incidence than in the control intoxicated animals (Fig. S4).

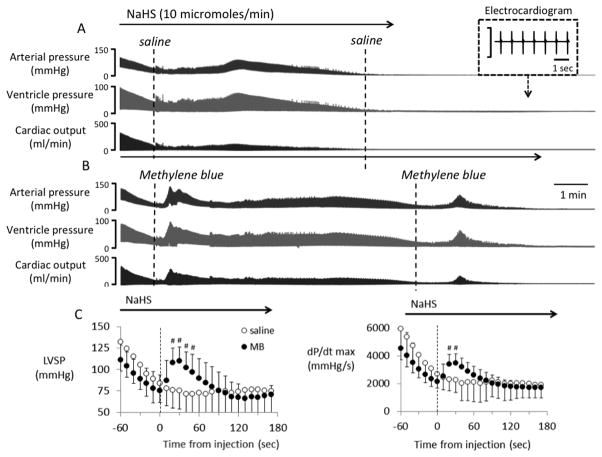

As a follow-up study and using a continuous infusion of NaHS (10–11 micromoles/min) in anesthetized rats that would be lethal in about 7–10 minutes 19, MB (4 mg/kg) or saline was injected as soon as the cardiac output reached 40% of its baseline value (within 2–3 minutes). We found that MB injection restored cardiac contractility (Fig. 5) blood pressure and cardiac output with very fast kinetics, and significantly prolonged the time to death19. Finally, to establish whether MB could affect the concentrations of H2S in solution during in vitro experiments, the amount of gaseous H2S released from a solution prepared from NaHS (100 microM, final quantity 1.5 micromoles) was measured in saline or PBS with or without MB (20mg/l). Solutions were placed in a sealed vial and the amount of H2S diffusing in the gaseous phase was analyzed after 10 minutes of incubation. We found that the entire amount of H2S present in solution was recovered from the medium, with fast kinetics, regardless of the presence of MB. This confirms our previous data 19 that no direct interaction between soluble H2S and MB are present.

Potential mechanisms of action of Methylene blue

First, LMB has potent reducing properties. This effect 65 has been proposed to account in part for the restoration of cognitive deficit in various models of brain dysfunction 64 and in post-anoxic brain injury 66. It is possible that its is through its reducing properties that LMB could rapidly restore the normal configuration of proteins in Ca2+ channels in the heart by cleaving disulfide bonds newly formed by SH− during sulfide intoxication 32, 34. The reducing properties of LMB could also affect the redox modulation of RyR or other calcium channels in relation to the numbers of sulfhydryl groups present. Indeed, H2S can lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species via a decrease in the electron transport chain activity 36, a damage that can be opposed by MB/LMB properties. MB has also been shown to reduce post-anoxic brain injury produced by a cardiac arrest 66, 67, which could account for the improvement of the longterm neurological outcome that we found. Second, MB supports the transfer of protons through the mitochondrial membrane against a concentration gradient, essential for the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), when mitochondrial respiration is impeded 68–70. Although this property remains quite controversial, MB could antagonize the mitochondrial mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide toxicity 29, 35. This mechanism may also account for the remarkable protection by MB against the toxic effects of the acute or chronic exposure 71 to sodium azide 72, another mitochondrial poison. Third, MB at low dose exerts a potent anti-nitric oxide (NO) effect 73, as MB inhibits guanylyl cyclase. This anti-NO effect 74 is the basis for treating refractory post-operative vasoplegia 75, 76, and could also be of interest during H2S poisoning.

Outstanding questions

How to treat intoxication by a gas, of which the pharmacokinetics and the mechanisms of toxicity remain poorly understood, is certainly a challenge. Trapping H2S, using cobalt or ferric compounds, is extremely effective on the pool of free H2S, but as this pool vanishes very rapidly after exposition, the relevance of these compounds on the intracellular pools of combined sulfide is problematic. Methylene blue does not combine with H2S and does not appear to affect its metabolism, but it is able to counteract some of the very acute effects of H2S on the heart and possibility the delayed effects of sulfide on the central nervous system. The acute effects of MB are of short duration following an IV administration but appears to be long enough to allow survival. It is unclear whether MB is effective during severe depression in cardiac contractility, wherein various and complex mechanisms of depression could be involved. Our present results suggest that the efficacy of MB decreases, as cardiac depression is more profound 18, 19. The benefit of other pheniothiazium chromophores 19, in association with “trapping” antidotes and specific cardiotonic agents must be investigated, keeping in mind that any increase in O2 demand may be deleterious for the heart and the central nervous system.

Conclusions

The effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) intoxication have too often been reduced to those that this gas shares with cyanide: an inhibition of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase activity. However, H2S displays a unique fate, as its soluble/diffusible form disappears extremely rapidly from the blood and tissues. If H2S does not kill a patient within seconds or minutes, it can dramatically affect cardiac contractility and affect various cortical and medullary functions via mechanisms not always related to a reduction in ATP production.

MB injection during the agonal phase of H2S induced coma in the rat is able to increase the survival rate and to improve the neurological outcome. These effects are the result of the rapid restoration of cardiac contractility depressed by sulfide. Whether MB counteracts the effects of H2S at the level of the Ca2+ channels or through another molecular mechanism remains to be determined. Finally, the doses at which MB should be used in a clinical setting await clarification.

Supplementary Material

Drawing illustrating the fate of the various pools of H2S during and after exposure to H2S. H2S in gaseous form is present in the blood and tissues in large part as HS− and combined with various metallo-proteins. Modified from Ref. 42.

Blood concentration of gaseous H2S (CgH2S) and total H2S (CMBBH2S) during recovery from sulfide intoxication produced by H2S infusion. Note the immediate decrease in gaseous H2S concentration in the blood as well as CMBBH2S, which remains significantly higher than baseline 15 min into recovery, but at levels well below toxic level. **P < 0.01. Modified from Ref. 46.

General outcome following intra-peritoneal injection of NaHS. Animals received an IP solution of H2S solution every 5 minutes until a coma occurred. From 1 to 3 injections were typically required. Whenever a coma occurs, it took about 2 minutes to develop after the last injection. The animals lost their righting reflex and became unresponsive. Then breathing became slow, leading to a gasping pattern. At this stage rats can spontaneously and progressively recover or continue to gasp until asystole occurs, typically within 7 minutes. Modified from Refs. 18 and 19.

(Left panel) Immediate outcome following intra-peritoneal injection of H2S solution, after receiving either saline (n = 8) or MB (n = 7) during the phase of agonal breathing. The top panel shows the histology of the frontal cerebral cortex in one of the intoxicated and untreated rat that displayed a motor deficit. The brain examination revealed diffuse and extended neuronal necrosis and neuropil edema affecting the outer frontal cortex. Similar necrotic lesions were found in the putamen and the thalamus. (Right panel) Long-term outcome evaluated by Morris Water Maze testing. There was a predominance of non-spatial search in the untreated animals during Morris water Maze testing in contrast to the animals that received methylene blue, that all displayed more effective swimming spatial strategies. Modified from Refs. 18 and 19.

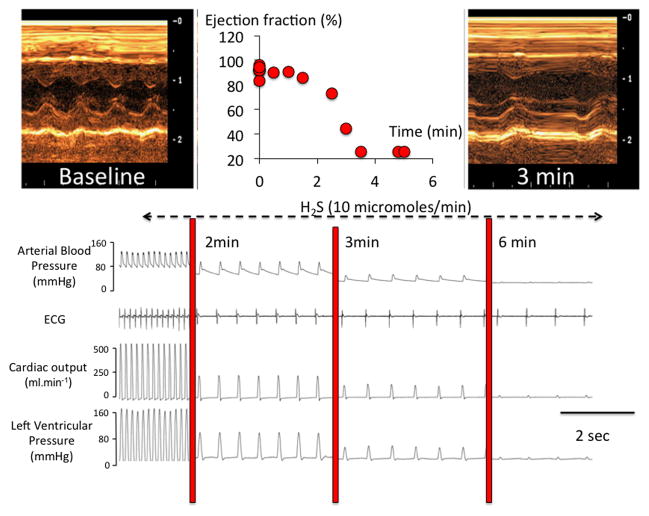

Figure 3.

Example of recordings obtained in anesthetized and mechanically ventilated rats, showing the effects of a continuous infusion NaHS (10 μmol/min) on hemodynamics and cardiac function. Top: echocardiographic data (TM mode) are illustrating the changes in left ventricle (LV) diameters during infusion, along with the rapid drop in ejection fraction. Bottom: blood pressure, EKG signal, cardiac output and left ventricular pressure are shown. Within few minutes only, H2S led to a complete pulseless electrical activity or electromechanical dissociation, as the heart becomes incapable of contracting despite a persistent electrical activity visible of the EKG signal. Modified from Refs. 19 and 20.

Figure 6.

Recordings showing the effects of a continuous infusion of NaHS (10 micromoles/min) on arterial blood pressure, ventricular pressure and cardiac output (CO) in two rats. (A) Saline was injected intravenously as soon as cardiac output (CO) decreased by ~60%. CO, blood pressure and ventricular became undetectable at 530 seconds. (B) Injection of 2 mg MB IV, in another rat, induced a large increase in CO and blood pressure. A second MB injection was able to produce a similar effect late into the period of intoxication, delaying the moment of death, despite continuous sulfide infusion. (C) Mean ± SD values of left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP) and dP/dtmax in rats receiving saline (open-circle) or 4 mg/kg MB (closed-circle) during lethal infusion of H2S (n = 14, 10 μmol/min). Saline and MB were injected at time 0 (dashed line); data were averaged every 10 seconds. Continuous H2S infusion decreased cardiac function and LVSP. Saline injection did not affect the decrease in LVSP and dP/dtmax. In contrast, MB had an immediate effect on circulation, significantly increasing the cardiac function and circulation for about 2 minutes. #, significantly different from pre-injection values, P < 0.05. Modified from Ref. 19.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms. Nicole Tubbs for her skillful technical assistance. This work has been supported by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (NIH OD), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Grant Number 1R21NS080788-01 and 1R21NS090017-01.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Bibilography

- 1.Arnold IM, et al. Health implication of occupational exposures to hydrogen sulfide. J Occup Med. 1985;27:373–376. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198505000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EPA. Toxicological Review of Hydrogen Sulfide (CAC No 7783-06-04) United States Environmental Protection Agency; Washington DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauchamp RO, Jr, et al. A critical review of the literature on hydrogen sulfide toxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1984;13:25–97. doi: 10.3109/10408448409029321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiffenstein RJ, Hulbert WC, Roth SH. Toxicology of hydrogen sulfide. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:109–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guidotti TL. Hydrogen sulphide. Occup Med (Lond) 1996;46:367–371. doi: 10.1093/occmed/46.5.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller DC, Suruda AJ. Occupationally related hydrogen sulfide deaths in the United States from 1984 to 1994. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:939–942. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200009000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chenard L, Lemay SP, Lague C. Hydrogen sulfide assessment in shallow-pit swine housing and outside manure storage. J Agric Saf Health. 2003;9:285–302. doi: 10.13031/2013.15458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass RI, et al. Deaths from asphyxia among fisherman. Jama. 1980;244:2193–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bott E, Dodd M. Suicide by hydrogen sulfide inhalation. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2013;34:23–25. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31827ab5ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagihara A, et al. The impact of newspaper reporting of hydrogen sulfide suicide on imitative suicide attempts in Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reedy SJ, Schwartz MD, Morgan BW. Suicide fads: frequency and characteristics of hydrogen sulfide suicides in the United States. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:300–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truscott A. Suicide fad threatens neighbours, rescuers. CMAJ. 2008;179:312–313. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenneman KA, et al. Olfactory neuron loss in adult male CD rats following subchronic inhalation exposure to hydrogen sulfide. Toxicol Pathol. 2000;28:326–333. doi: 10.1177/019262330002800213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorman DC, et al. Cytochrome oxidase inhibition induced by acute hydrogen sulfide inhalation: correlation with tissue sulfide concentrations in the rat brain, liver, lung, and nasal epithelium. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:18–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klingerman CM, et al. H2S concentrations in the arterial blood during H2S administration in relation to its toxicity and effects on breathing. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R630–638. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00218.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haouzi P, et al. In Vivo Interactions Between Cobalt or Ferric Compounds and the Pools of Sulphide in the Blood During and After H2S Poisoning. Toxicol Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guidotti TL. Hydrogen sulfide: advances in understanding human toxicity. Int J Toxicol. 2010;29:569–581. doi: 10.1177/1091581810384882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonobe T, et al. Immediate and Long-Term Outcome of Acute H2S Intoxication Induced Coma in Unanesthetized Rats: Effects of Methylene Blue. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonobe T, Haouzi P. H2S induced coma and cardiogenic shock in the rat: Effects of phenothiazinium chromophores. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:525–539. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1043440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonobe T, Haouzi P. Sulfide Intoxication-Induced Circulatory Failure is Mediated by a Depression in Cardiac Contractility. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haouzi P, Sonobe T. Cardiogenic shock induced reduction in cellular O2 delivery as a hallmark of acute H2S intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:416–417. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1014908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haouzi P, Chenuel B, Sonobe T. High-dose hydroxocobalamin administered after H2S exposure counteracts sulfide-poisoning-induced cardiac depression in sheep. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:28–36. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.990976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldelli RJ, Green FH, Auer RN. Sulfide toxicity: mechanical ventilation and hypotension determine survival rate and brain necrosis. Journal of applied physiology. 1993;75:1348–1353. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.3.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tvedt B, et al. Brain damage caused by hydrogen sulfide: a follow-up study of six patients. Am J Ind Med. 1991;20:91–101. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenneman KA, et al. Olfactory mucosal necrosis in male CD rats following acute inhalation exposure to hydrogen sulfide: reversibility and the possible role of regional metabolism. Toxicol Pathol. 2002;30:200–208. doi: 10.1080/019262302753559533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez A, et al. Peracute toxic effects of inhaled hydrogen sulfide and injected sodium hydrosulfide on the lungs of rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989;12:367–373. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan AA, et al. Effects of hydrogen sulfide exposure on lung mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;103:482–490. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90321-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorman DC, et al. Cytochrome oxidase inhibition induced by acute hydrogen sulfide inhalation: correlation with tissue sulfide concentrations in the rat brain, liver, lung, and nasal epithelium. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:18–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper CE, Brown GC. The inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase by the gases carbon monoxide, nitric oxide, hydrogen cyanide and hydrogen sulfide: chemical mechanism and physiological significance. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:533–539. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eghbal MA, Pennefather PS, O’Brien PJ. H2S cytotoxicity mechanism involves reactive oxygen species formation and mitochondrial depolarisation. Toxicology. 2004;203:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul BD, Snyder SH. H(2)S signalling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:499–507. doi: 10.1038/nrm3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang R, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits L-type calcium currents depending upon the protein sulfhydryl state in rat cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mustafa AK, et al. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun YG, et al. Hydrogen sulphide is an inhibitor of L-type calcium channels and mechanical contraction in rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:632–641. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouillaud F, Blachier F. Mitochondria and sulfide: a very old story of poisoning, feeding, and signaling? Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;15:379–391. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zima AV, Blatter LA. Redox regulation of cardiac calcium channels and transporters. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide regulates cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) uptake via K(ATP) channel and PI3K/Akt pathway. Life Sci. 2012;91:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Telezhkin V, et al. Mechanism of inhibition by hydrogen sulfide of native and recombinant BKCa channels. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;172:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greer JJ, et al. Sulfide-induced perturbations of the neuronal mechanisms controlling breathing in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:433–440. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodwin LR, et al. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue by gas dialysis/ion chromatography: postmortem studies and two case reports. J Anal Toxicol. 1989;13:105–109. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carroll JJ, Mather AE. The solubility of hydrogen sulfide in water from 0 to 90°C and pressures to 1 MPa. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1989;53:1163–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furne J, Saeed A, Levitt MD. Whole tissue hydrogen sulfide concentrations are orders of magnitude lower than presently accepted values. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1479–1485. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90566.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Douabul AA, Riley JP. The solubility of gases in distilled water and seawater - V. Hydrogen sulphide. Deep-Sea Research. 1979;26A:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Millero FJ. The thermodynamics and kinetics of hydrogen sulfide system in natural waters. Marine Chemistry. 1986;18:121–147. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wintner EA, et al. A monobromobimane-based assay to measure the pharmacokinetic profile of reactive sulphide species in blood. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:941–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toombs CF, et al. Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas in healthy human volunteers during intravenous administration of sodium sulphide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:626–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haggard HW. The fate of sulfides in the blood. J Biol Chem. 1921;49:519–529. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lagoutte E, et al. Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide remains a priority in mammalian cells and causes reverse electron transfer in colonocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1500–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Picton R, et al. Mucosal protection against sulphide: importance of the enzyme rhodanese. Gut. 2002;50:201–205. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson K, et al. Differentiation of the roles of sulfide oxidase and rhodanese in the detoxification of sulfide by the colonic mucosa. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2008;53:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9854-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warenycia MW, et al. Dithiothreitol liberates non-acid labile sulfide from brain tissue of H2S-poisoned animals. Arch Toxicol. 1990;64:650–655. doi: 10.1007/BF01974693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chenuel B, Sonobe T, Haouzi P. Effects of infusion of human methemoglobin solution following hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:93–101. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.996570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haouzi P, Klingerman CM. Fate of intracellular H2S/HS(-) and metallo-proteins. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;188:229–230. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van de Louw A, Haouzi P. Ferric Iron and Cobalt (III) compounds to safely decrease hydrogen sulfide in the body? Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2013;19:510–516. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Truong DH, et al. Prevention of hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-induced mouse lethality and cytotoxicity by hydroxocobalamin (vitamin B(12a)) Toxicology. 2007;242:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haouzi P, Bell H, Van de Louw A. Hypoxia-induced arterial chemoreceptor stimulation and hydrogen sulfide: too much or too little? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;179:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kohn MC, et al. Pharmacokinetics of sodium nitrite-induced methemoglobinemia in the rat. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:676–683. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith L, Kruszyna H, Smith RP. The effect of methemoglobin on the inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase by cyanide, sulfide or azide. Biochem Pharmacol. 1977;26:2247–2250. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(77)90287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mihajlovic A. PhD PhD Thesis. Toronto: 1999. Antidotal mechanisms for hydrogen sulfide toxicity. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Astier A, Baud FJ. Complexation of intracellular cyanide by hydroxocobalamin using a human cellular model. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1996;15:19–25. doi: 10.1177/096032719601500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burrows GE. Methylene blue: effects and disposition in sheep. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1984;7:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.1984.tb00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peter C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and organ distribution of intravenous and oral methylene blue. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:247–250. doi: 10.1007/s002280000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clifton J, 2nd, Leikin JB. Methylene blue. Am J Ther. 2003;10:289–291. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rojas JC, Bruchey AK, Gonzalez-Lima F. Neurometabolic mechanisms for memory enhancement and neuroprotection of methylene blue. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;96:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oz M, et al. Cellular and molecular actions of Methylene Blue in the nervous system. Med Res Rev. 2011;31:93–117. doi: 10.1002/med.20177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wiklund L, et al. Improved neuroprotective effect of methylene blue with hypothermia after porcine cardiac arrest. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:1073–1082. doi: 10.1111/aas.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miclescu A, Basu S, Wiklund L. Cardio-cerebral and metabolic effects of methylene blue in hypertonic sodium lactate during experimental cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2007;75:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang X, Rojas JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue prevents neurodegeneration caused by rotenone in the retina. Neurotox Res. 2006;9:47–57. doi: 10.1007/BF03033307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scott A, Hunter FE., Jr Support of thyroxine-induced swelling of liver mitochondria by generation of high energy intermediates at any one of three sites in electron transport. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:1060–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindahl PE, Oberg KE. The effect of rotenone on respiration and its point of attack. Exp Cell Res. 1961;23:228–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Callaway NL, et al. Methylene blue restores spatial memory retention impaired by an inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Riha PD, Rojas JC, Gonzalez-Lima F. Beneficial network effects of methylene blue in an amnestic model. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2623–2634. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gruetter CA, Kadowitz PJ, Ignarro LJ. Methylene blue inhibits coronary arterial relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation by nitroglycerin, sodium nitrite, and amyl nitrite. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1981;59:150–156. doi: 10.1139/y81-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiklund L, et al. Neuro- and cardioprotective effects of blockade of nitric oxide action by administration of methylene blue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1122:231–244. doi: 10.1196/annals.1403.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kofidis T, et al. Reversal of severe vasoplegia with single-dose methylene blue after heart transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:823–824. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.115153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leyh RG, et al. Methylene blue: the drug of choice for catecholamine-refractory vasoplegia after cardiopulmonary bypass? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:1426–1431. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haouzi P. Ventilatory and metabolic effects of exogenous hydrogen sulfide. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;184:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Drawing illustrating the fate of the various pools of H2S during and after exposure to H2S. H2S in gaseous form is present in the blood and tissues in large part as HS− and combined with various metallo-proteins. Modified from Ref. 42.

Blood concentration of gaseous H2S (CgH2S) and total H2S (CMBBH2S) during recovery from sulfide intoxication produced by H2S infusion. Note the immediate decrease in gaseous H2S concentration in the blood as well as CMBBH2S, which remains significantly higher than baseline 15 min into recovery, but at levels well below toxic level. **P < 0.01. Modified from Ref. 46.

General outcome following intra-peritoneal injection of NaHS. Animals received an IP solution of H2S solution every 5 minutes until a coma occurred. From 1 to 3 injections were typically required. Whenever a coma occurs, it took about 2 minutes to develop after the last injection. The animals lost their righting reflex and became unresponsive. Then breathing became slow, leading to a gasping pattern. At this stage rats can spontaneously and progressively recover or continue to gasp until asystole occurs, typically within 7 minutes. Modified from Refs. 18 and 19.

(Left panel) Immediate outcome following intra-peritoneal injection of H2S solution, after receiving either saline (n = 8) or MB (n = 7) during the phase of agonal breathing. The top panel shows the histology of the frontal cerebral cortex in one of the intoxicated and untreated rat that displayed a motor deficit. The brain examination revealed diffuse and extended neuronal necrosis and neuropil edema affecting the outer frontal cortex. Similar necrotic lesions were found in the putamen and the thalamus. (Right panel) Long-term outcome evaluated by Morris Water Maze testing. There was a predominance of non-spatial search in the untreated animals during Morris water Maze testing in contrast to the animals that received methylene blue, that all displayed more effective swimming spatial strategies. Modified from Refs. 18 and 19.