Abstract

PURPOSE

We set out to assess whether a high sense of coherence (SOC) protects from adverse health outcomes in patients aged 80 years and older who have multiple chronic diseases.

METHODS

A population-based prospective cohort study in 29 primary care practices throughout Belgium included 567 individuals aged 80 years and older. We plotted the highest tertile of SOC scores in Kaplan-Meier curves representing 3-year mortality and time to first hospitalization. Using Cox proportional hazard regression analyses and multiple logistic regression analyses adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, depression, cognition, disability, and multimorbidity we examined the relationship between SOC and mortality, hospitalization, and decline in performance of activities of daily living (ADL).

RESULTS

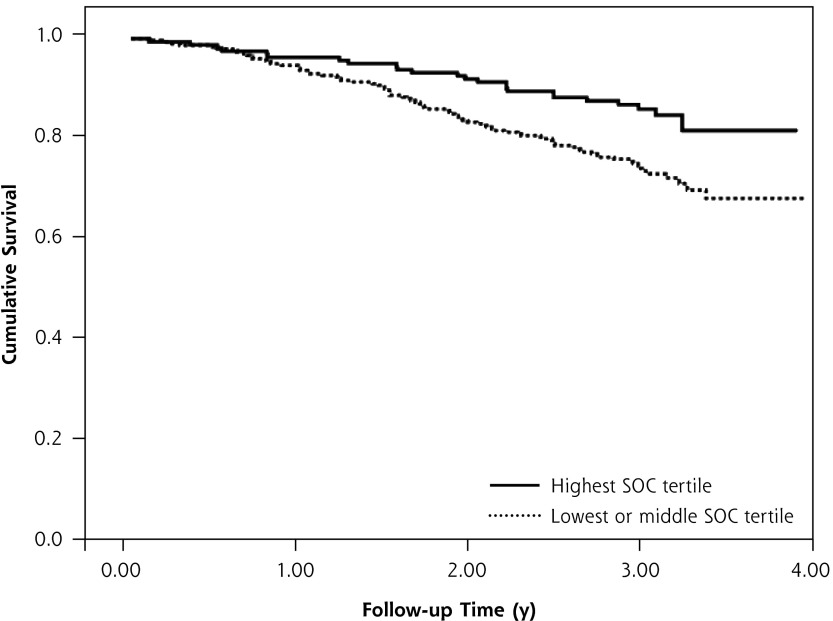

Subjects with high SOC scores showed a higher cumulative survival than others (Log rank = 0.004) independent of other prognostic characteristics (adjusted hazard ratio 0.62 (95% CI, 0.38–1.00), P = .049). For ADL decline, a high SOC was shown to be protective, and this effect tended to be independent from the covariates under study (adjusted odds ratio 0.56 (95% CI, 0.31–1.0), P = .05).

CONCLUSION

Even very elderly persons with high SOC scores were shown to have lower mortality rates and less functional decline. These effects were independent of multimorbidity, depression, cognition, disability, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Keywords: sense of coherence; multimorbidity; depression; aged, 80 and over; mortality; functional decline

INTRODUCTION

Older people very often suffer from multiple chronic diseases. The relationships between multimorbidity and adverse outcomes such as disability, mortality, hospitalization, and functional decline, however, are far from linear.1–4 Most studies have assessed the impact of negative modifiers such as deprivation, depressive symptoms, or cognitive decline. These models, however, might overlook people’s strengths and hamper a positive approach toward healthy aging. In the 1970s, Antonovsky defined the concept of the sense of coherence (SOC) while working on a model focusing on factors that support human health and well-being, rather than on factors that cause disease.5 The SOC can be evaluated by means of a questionnaire assessing 3 components:

Comprehensibility (the extent to which one perceives events as making sense—as being ordered, consistent, and structured)

Manageability (the extent to which one feels he or she can cope)

Meaningfulness (the extent to which one feels that life makes sense and that challenges are worthy of commitment).6–8

High SOC scores have been shown to protect from negative health outcomes in terms of perceived health,7 quality of life,7,9 mortality,10–13 and disability.14,15 Most studies have been carried out on people with specific diseases14,16–18 or in young populations.10,11,19 Recently, a review on sense of coherence in people aged 65 and older confirmed the positive associations between the sense of coherence, perceived health, and quality of life.20 There is, however, a lack of longitudinal studies assessing the effect of SOC. The current study aims to assess whether a high sense of coherence protects from adverse outcomes in a cohort of patients aged 80 years and older independent of other prognostic characteristics such as multimorbidity, disability, depression, cognition, and sociodemographic variables.

METHODS

Study Population

The BELFRAIL (BFC80+) study is a prospective, observational, population-based cohort study of 567 individuals aged 80 years and older in Belgium. The study design and characteristics of the cohort have been described in detail.21 Only 3 exclusion criteria were used: severe dementia (mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score less than 15), being in palliative care, and having a medical emergency. Participants were enrolled between November 2008 and September 2009.

Baseline Sense of Coherence

The 13-item SOC questionnaire assesses the 3 components of SOC. Every item is scored with a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7, generating a total scale range from 13 to 91, a higher score representing a stronger SOC.6 We determined tertiles of the total score and divided the participants into a high-SOC group and a medium/low-SOC group at the higher tertile.

Baseline Multimorbidity

Each participant’s family physician recorded the presence or absence of 22 chronic diseases at baseline. The number of chronic diseases a patient had was used as a measure of multimorbidity. Previous analyses in this study have indicated that more sophisticated measures of multimorbidity such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index22 and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale23 have no added value over a simple disease count in relation to frailty, disability, mortality, hospitalization, and functional decline.1,2

Covariates

The participants’ family physicians recorded sex, level of education, and marital status. The clinical research associate assessed functional limitations by asking the respondents the degree of difficulty they had with 6 activities of daily living (ADLs) at baseline (T0).24 Disability was defined as the lowest sex-specific quartile of ADL performance. Depressive symptoms (15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) score of more than 5)25 and cognitive dysfunction (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score categories)26 were included as separate covariates in the analysis because they are highly prevalent in the older population,27,28 often remain unrecognized, and are accompanied by increased morbidity and mortality.29

Outcome Measurements

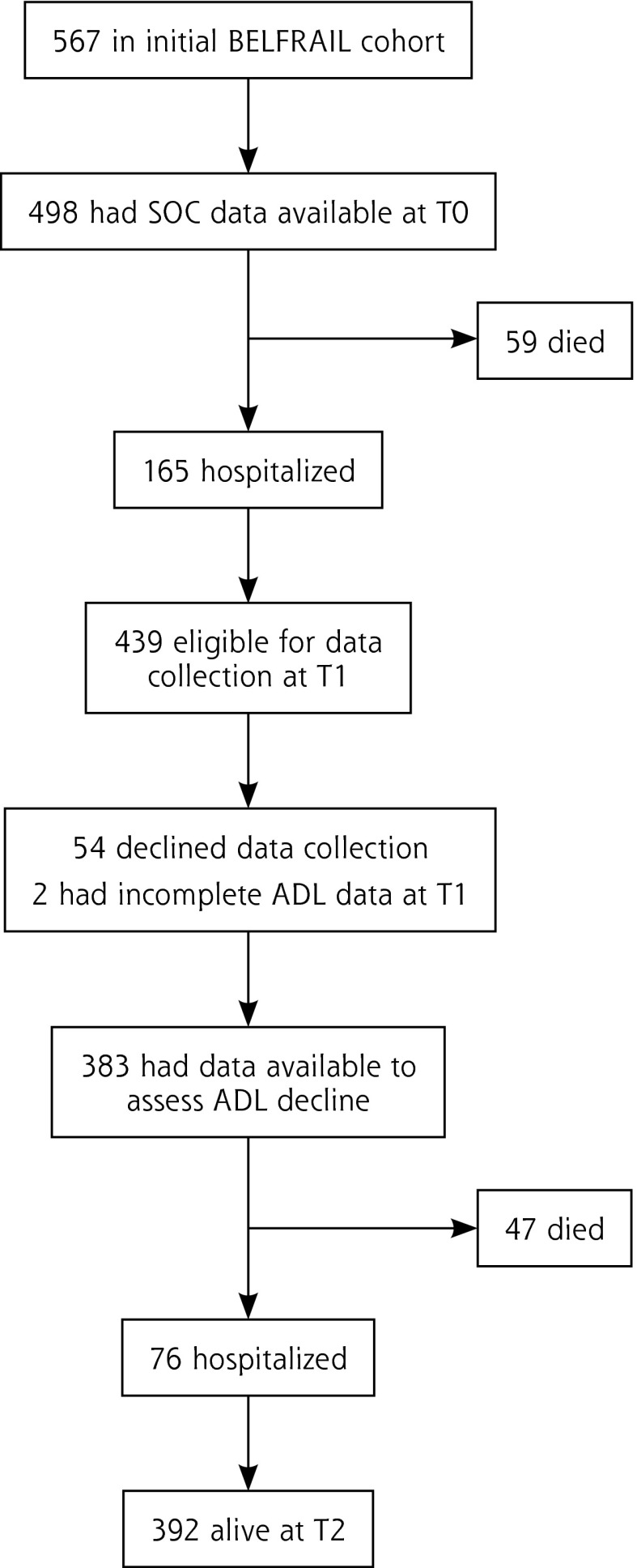

All-cause mortality and time to first non-planned hospitalization were recorded from the participating practices at T1 (18 months [19.6 ± 2.5 months] after enrollment) and at T2 (3 years [3 ± 0.25 years] after enrollment; Figure 1). Data on functional status30 were recorded at T0 and T1 but not at T2. Functional decline was defined as substantial individual change in the ability to perform ADLs between T0 and T1 as measured by the Edwards-Nunnally index.31

Figure 1.

Participation flow chart.

ADL = activities of daily living; SOC = sense of coherence.

Data Analysis

We plotted the highest tertile of SOC scores against the lower tertiles in Kaplan-Meier curves representing 3-year cumulative survival and time to first hospitalization using a log rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to examine whether these relationships were independent of multimorbidity, baseline disability, depression, cognition, and sociodemographic covariates. Multiple logistic regression analyses, adjusting for the same covariates, examined the relationship between SOC and functional decline. The data analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation).

RESULTS

The mean age of the 567 participants of the BFC80+ study was 84.7 ± 3.7 years; 63% (356) of the participants were women. The morbidity burden was high: each participant had at least 1 chronic disease; 96% (544) had more than 1 disease, and 38% (213) had 5 or more chronic diseases (range 1–16). The most frequent disorders were hypertension (67% of the population) and osteoarthritis (57% of the population).

At enrollment, 498 participants answered the SOC-13 questionnaire (Figure 1). Subjects in the highest tertile of SOC scored at least 82. A high SOC score was related to male sex, being married, and having intact cognition; it was inversely related to depression, baseline disability, and multimorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics

| Variables | Total Population (n = 498) | Sense of Coherence (SOC)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Low SOC (n = 324) | High SOC (Highest Tertile) (n = 174) | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 84.8 (3.7) | 85.0 (3.9) | 84.4 (3.4) |

| Men, No. (%) | 183 (36.7) | 98 (30.2) | 85 (48.9)a |

| Family situation, No. (%) | |||

| Married | 211 (42.6) | 119 (37.1) | 92 (52.9)b |

| Divorced | 9 (1.8) | 8 (2.5) | 0 (0) |

| Widow or widower | 249 (50.3) | 179 (55.8) | 70 (40.2) |

| Single | 16 (3.2) | 8 (2.5) | 8 (4.6) |

| Other | 10 (2.0) | 6 (1.9) | 4 (2.3) |

| Level of education > primary school, No. (%) | 313 (63.2) | 194 (60.4) | 119 (68.4) |

| Baseline data | |||

| Depressive symptoms (GDS-15 score >5), No. (%) | 95 (19.1) | 77 (23.8) | 18 (10.3)a |

| MMSE score, No. (%) | |||

| 25–30 | 405 (81.3) | 248 (76.5) | 157 (90.2)a |

| 21–24 | 62 (12.4) | 47 (14.5) | 15 (8.6) |

| ≤20 | 31 (6.2) | 29 (9.0) | 2 (1.1) |

| ADL score, median (IQR) | 25 (21–27) | 24 (20–27) | 26 (23–29)a |

| Disease count, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (2–5)b |

| Outcomes | |||

| Mortality, No. (%) | 106 (21) | 91 (25.5)a | 10 (10.4)a |

| Hospitalization, No. (%) | 241 (49.0) | 178 (51.0) | 63 (44.1) |

| ADL decline, No. (%) | 96 (25.1) | 76 (28.7)b | 20 (16.9)b |

ADL = activities of daily living; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; IQR = interquartile range; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

P <.001.

P <.05.

The mortality rate at T2 was 21% (106), and at least 1 hospitalization was reported for each of 241 participants (48%). For those with high SOC scores, the mortality rate at T2 was 13.8% (24), with hospitalizations reported for 81 (46.5%). Kaplan-Meier curves showed a higher cumulative survival for subjects in the highest SOC tertile (Log-rank = 0.004) (Figure 2), but this relationship was not demonstrated for hospitalization. Cox proportional hazard regression analyses confirmed the relationship between a high SOC score and mortality (adjusted HR 0.62 [95% CI, 0.38–1.0], P = .049; Table 2).

Figure 2.

The predictive value of a high SOC score for survival from all-cause mortality.

SOC = sense of coherence.

Table 2.

Predictive Value of Sociodemographic Characteristics, SOC, Baseline Disability, Indicators of Mental Functioning, and Measures of Multimorbidity for Mortality, Hospitalization, and ADL Decline

| Characteristic | Mortality (n = 106) | Hospitalization (n = 241) | ADL Decline (n = 96) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Crude Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| SOC (highest tertile) | 0.52 (0.33–0.81)a | 0.62 (0.38–1.0)a | 0.87 (0.66–1.1) | 0.90 (0.68–1.2) | 0.51 (0.30–0.89)a | 0.56 (0.31–1.0)b |

| Age | 1.1 (1.0–1.1)a | 1.0 (0.99–1.1) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1)a | 1.0 (0.99–1.1) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2)a | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)a |

| Men | 1.0 (0.68–1.5) | 1.3 (0.87–2.0) | 1.1 (0.89–1.5) | 1.3 (0.87–2.0) | 1.2 (0.72–1.9) | 1.2 (0.69–2.1) |

| Family situation | 1.2 (1.0–1.5)a | 1.2 (0.96–1.4) | 0.98 (0.87–1.1) | 1.2 (0.96 –1.4) | 0.95 (0.77–1.2) | 0.83 (0.64–1.1) |

| Level of education > primary school | 1.0 (0.69–1.5) | 1.4 (0.92–2.1) | 1.2 (0.92–1.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)a | 1.0 (0.62–1.6) | 1.2 (0.73–2.1) |

| GDS-15 score >5 | 1.6 (1.0–2.4)a | 0.94 (0.59–1.5) | 1.3 (0.97–1.8) | 1.1 (0.78–1.5) | 1.0 (0.57–1.9) | 0.85 (0.43–1.7) |

| MMSE (categories) | 2.0 (1.5–2.6)c | 1.8 (1.3–2.3)c | 1.3 (1.1–1.6)a | 1.3 (1.1–1.6)a | 2.1 (1.4–3.1)a | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) |

| ADL disability (lowest sex-specific quartile) | 2.9 (2.0–4.3)c | 2.1 (1.4–3.3)a | 1.9 (1.4–2.6)c | 1.6 (1.2–2.3)a | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.97 (0.50–1.9) |

| DC (categories)d | 1.5 (1.2–1.9)c | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)a | 1.6 (1.4–1.9)c | 1.6 (1.4–1.9)c | 1.0 (0.77–1.4) | 0.98 (0.71–1.3) |

ADL = activities of daily living; DC = disease count; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SOC = sense of coherence.

P <.05.

P = .05.

P <.001.

Disease count categories: Level 1: DC <3; level 2: DC 3–4; level 3: DC >5.

At T1, 96 participants (25.1% of the 383 who underwent a second examination by the clinical research associate) showed a decline in ADL score. For those with high SOC scores, 16.9% (20) showed ADL decline at T1. Bivariate analysis showed an inverse correlation between a high SOC and ADL decline (crude OR 0.51 [95% CI, 0.30–0.89], P < .05; Table 2). The multivariate analysis indicated a trend for the protective effect of a high SOC (adjusted OR 0.56 [95% CI, 0.31–1.0], P = .05).

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

Even quite elderly persons with high SOC scores were shown to have lower mortality rates and less functional decline than the study population as a whole. These effects were independent of multimorbidity, depression, cognition, disability, and sociodemographic characteristics. The SOC has previously been defined as a potential resource for improving health-related quality of life in patients with chronic diseases.32 Our study indicates that the protective effect of the SOC extends beyond perceived health and quality of life toward mortality and functional decline, even in a population with a high vulnerability to adverse outcomes.

Comparison With Existing Literature

Regarding mortality, 4 other studies have indicated that SOC has a protective effect,10,11,13,33,34 however, these studies were performed in younger populations.11,34 For the oldest age-groups we can only refer to the Umeå 85+ study. The Umeå 85+ study included 109 patients aged 85 years and older.35 Within the Umeå 85+ study population, 1-year mortality appeared to be significantly associated with SOC, while 4-year mortality was not. Longer follow-up analyses should indicate whether the protective effects we have observed fade or persist. Our study could not identify a relationship between a high SOC score and the risk of future hospitalization. No previous studies on SOC have assessed hospitalization as an outcome measure. Our finding that a high SOC score tends to protect from a decline in functional status is in line with a study among Finnish patients with anterior low-back fusion.36 The Finnish study showed that during a 5-year follow-up period SOC scores had a good predictive value for disability. The shorter follow-up time in our study (19.6 ± 2.5 months for ADL decline) might explain why the relationship we found did not reach significance.

Many other studies of SOC have adjusted their analyses for the health status of the study participants.37–40 This is one of the first studies of SOC in a vulnerable population with high morbidity rates. The Umeå 85+ study assessed the relationship between SOC scores and 21 chronic illnesses within a population of patients aged 85 years or older and demonstrated a relationship between low SOC and heart failure, COPD, depression, and osteoarthritis but not other diseases.41 Our study is the first to include multimorbidity as a covariate. Multimorbidity was measured by means of a simple disease count, but the analyses performed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index22 and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale23,42,43 showed similar results.

Strengths and Limitations

Numerous cross-sectional studies have found a high SOC to be related to better-perceived health, but only a few prospective cohort studies have examined the protective effect of SOC, and this is the first study to assess associations between SOC and several health-related outcomes in a vulnerable population aged 80 years and older. The demonstrated relationships were assessed by means of a multivariate analysis, including important covariates like the number of chronic diseases, depression, cognition, and sociodemographic characteristics, which have all been identified as important confounders in previous SOC-related studies. A limitation of the study is that it didn’t inquire about earlier life events that might have contributed to the construction of SOC. Nor did it inquire about later life events—events during the study, for instance—that may have modified the relation between SOC and the outcomes under study. Moreover, even though this study included a considerable number of participants, it did not include enough to achieve narrow CIs and clearly significant P values.

Even though the SOC is psychometrically sound, its use has some limitations.40 First, while many studies have indicated high SOC scores to be protective, these studies have provided no clear indication as to which cut-off points to use. Because SOC scores are skewed, we have used the highest tertile to define a high SOC and can at least state that, in persons aged 80 years or older, SOC scores in the highest tertile are protective for adverse health outcomes. Second, despite the fact that the SOC questionnaire has previously been used among older adults,9,44–48 the fact that SOC has to be assessed by means of a questionnaire limits all studies on the role of SOC in older people to the people who are able to administer the questionnaire.

Implications of Our Results

Given the protective effects of SOC, it may be important to further explore interventions for increasing SOC in people with low scores, in hopes of improving their capacity to cope with life stressors and maintain their health. There is currently no consensus, however, on whether the SOC is a fixed personality trait or whether people’s sense of coherence can be modified by interventions.41,49 Our study does not bear on this question, but it does suggest an answer to the question why people with a comparable burdens of chronic disease have different prognoses. Our findings counter the argument that SOC would be merely the inverse of depression50 and suggest the importance of further research into patients’ strengths and not merely their limitations and vulnerability. Whether the SOC will evolve to a clinically applicable concept is yet unclear.41,49

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by the participating general practitioners and their patients: Dr Etienne Baijot (Beauraing), Dr Pierre Leclercq (Pondrôme), Dr Baudouin Demblon (Wellin), Dr Daniel Simon (Rochefort), Dr Daniel Vanthuyne (Celles), Dr Yvan Mouton (Godinne), Dr Louis-Philippe Docquier (Maffe), Dr Tanguy Dethier (Ciney), Dr Patricia Eeckeleers (Leignon), Dr Jean-Paul Decaux (Dinant), Dr Christian Fery (Dinant), Dr Pascale Pierret (Heure), Dr Paul-Emile Blondeau (Beauraing), Dr Baudry Gubin (Beauraing), Dr Jacques Guisset (Wellin), Dr Quentin Gillet (Mohiville), Dr Arlette Germay (Houyet), Dr Jan Craenen (Hoeilaart), Dr Luc Meeus (Hoeilaart), Dr Herman Docx (Hoeilaart), Dr Ann Van Damme (Hoeilaart), Dr Sofie Dedeurwaerdere (Hoeilaart), Dr Bert Vaes (Hoeilaart), Dr Stein Bergiers (Hoeilaart), Dr Bernard Deman (Hoeilaart), Dr Edmond Charlier (Overijse), Dr Serge Tollet (Overijse), Dr Eddy Van Keerberghen (Overijse), Dr Etienne Smets (Overijse), Dr Yves Van Exem (Overijse), Dr Lutgart Deridder (Overijse), Dr Jan Degryse (Oudergem), Dr Katrien Van Roy (Oudergem), Dr Veerle Goossens (Tervuren), Dr Herman Willems (Overijse), and Dr Marleen Moriau (Bosvoorde).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Author contributions: P.B. is the main author of the study. She was responsible for the analyses and the writing of the manuscript. B.V. has been involved in the design of the study, data collection, and assisted both in the data analysis and writing of the manuscript. G.V.P., C.M., and W.A. have all been actively involved in the data collection and were involved in the development of the research questions of the paper and strategies for data analysis. I.A. provided her expertise in the interpretation of the results. A.D.S. and J.D. supervised the data analysis and writing of the manuscript. J.D. is the leading researcher of the BELFRAIL study.

Funding support: Pauline Boeckxstaens was supported by a grant of the research foundation Flanders (FWO). The BELFRAIL study (B40320084685) was supported by an unconditional grant from the Fondation Louvain. The Fondation Louvain is the support unit of the Université Catholique de Louvain and is charged with developing the educational and research projects of the university by collecting gifts from corporations, foundations, and alumni.

References

- 1.Boeckxstaens P, Vaes B, Legrand D, Dalleur O, De Sutter A, Degryse JM. The relationship of multimorbidity with disability and frailty in the oldest patients: a cross-sectional analysis of three measures of multimorbidity in the BELFRAIL cohort. Eur J Gen Pract. 2015; 21(1):39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeckxstaens P, Vaes B, Van Pottelbergh G, et al. Multimorbidity measures were poor predictors of adverse events in patients aged ≤80 years: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(2):220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brilleman SL, Salisbury C. Comparing measures of multimorbidity to predict outcomes in primary care: a cross sectional study. Fam Pract. 2013;30(2):172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Bari M, Virgillo A, Matteuzzi D, et al. Predictive validity of measures of comorbidity in older community dwellers: the Insufficienza Cardiaca negli Anziani Residenti a Dicomano Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(2):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):460–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drageset J, Eide GE, Nygaard HA, Bondevik M, Nortvedt MW, Natvig GK. The impact of social support and sense of coherence on health-related quality of life among nursing home residents—a questionnaire survey in Bergen, Norway. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; 46(1):65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poppius E, Tenkanen L, Hakama M, Kalimo R, Pitkänen T. The sense of coherence, occupation and all-cause mortality in the Helsinki Heart Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18(5):389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surtees P, Wainwright N, Luben R, Khaw KT, Day N. Sense of coherence and mortality in men and women in the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(12): 1202–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wainwright NW, Surtees PG, Welch AA, Luben RN, Khaw KT, Bingham SA. Sense of coherence, lifestyle choices and mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(9):829–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Luben R, Khaw KT, Day NE. Mastery, sense of coherence, and mortality: evidence of independent associations from the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Cohort Study. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsson LJ, Westerberg M, Malec JF, Lexell J. Sense of coherence and disability and the relationship with life satisfaction 6–15 years after traumatic brain injury in northern Sweden. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2011;21(3):383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundman B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, et al. Inner strength in relation to functional status, disease, living arrangements, and social relationships among people aged 85 years and older. Geriatr Nurs. 2012; 33(3):167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silarova B, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, et al. Sense of coherence as an independent predictor of health-related quality of life among coronary heart disease patients. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(10): 1863–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pusswald G, Fleck M, Lehrner J, Haubenberger D, Weber G, Auff E. The “Sense of Coherence” and the coping capacity of patients with Parkinson disease. International Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(12): 1972–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benz T, Angst F, Lehmann S, Aeschlimann A. Association of the sense of coherence with physical and psychosocial health in the rehabilitation of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrikx T, Nilsson M, Westman G. Sense of coherence in three cross-sectional studies in Northern Sweden 1994, 1999 and 2004 — patterns among men and women. Scand J Public Health. 2008; 36(4):340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan KK, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K, Chan SW. Integrative review: salutogenesis and health in older people over 65 years old. J Adv Nurs. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaes B, Pasquet A, Wallemacq P, et al. The BELFRAIL (BFC80+) study: a population-based prospective cohort study of the very elderly in Belgium. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudon C, Fortin M, Soubhi H. Abbreviated guidelines for scoring the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) in family practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(2):212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McWhinnie JR. Disability assessment in population surveys: results of the O.E.C.D. Common Development Effort. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1981;29(4):413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients. A comparison of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(4):449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(9):922–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stek ML, Gussekloo J, Beekman AT, van Tilburg W, Westendorp RG. Prevalence, correlates and recognition of depression in the oldest old: the Leiden 85-plus study. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(3):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stek ML, Vinkers DJ, Gussekloo J, van der Mast RC, Beekman AT, Westendorp RG. Natural history of depression in the oldest old: population-based prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapid MI, Rummans TA. Evaluation and management of geriatric depression in primary care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(11):1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puts MT, Lips P, Deeg DJ. Static and dynamic measures of frailty predicted decline in performance-based and self-reported physical functioning. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(11):1188–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Speer DC, Greenbaum PE. Five methods for computing significant individual client change and improvement rates: support for an individual growth curve approach. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(6):1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogel I, Miksch A, Goetz K, Ose D, Szecsenyi J, Freund T. The impact of perceived social support and sense of coherence on health-related quality of life in multimorbid primary care patients. Chronic Illn. 2012;8(4):296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haukkala A, Konttinen H, Lehto E, Uutela A, Kawachi I, Laatikainen T. Sense of coherence, depressive symptoms, cardiovascular diseases, and all-cause mortality. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(4):429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Super S, Verschuren WM, Zantinge EM, Wagemakers MA, Picavet HS. A weak sense of coherence is associated with a higher mortality risk. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(5):411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundman B, Forsberg KA, Jonsén E, et al. Sense of coherence (SOC) related to health and mortality among the very old: the Umeå 85+ study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(3):329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santavirta N, Bjorvell H, Konttinen YT, Solovieva S, Poussa M, Santavirta S. Sense of coherence and outcome of low-back surgery: 5-year follow-up of 80 patients. Eur Spine J. 1996;5(4):229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nygren B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moe A, Hellzen O, Ekker K, Enmarker I. Inner strength in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old people with chronic illness. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(2):189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flensborg-Madsen T, Ventegodt S, Merrick J. Sense of coherence and physical health. A review of previous findings. ScientificWorld-Journal. 2005;5:665–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veenstra M, Moum T, Røysamb E. Relationships between health domains and sense of coherence: a two-year cross-lagged study in patients with chronic illness. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(6):1455–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lövheim H, Graneheim UH, Jonsén E, Strandberg G, Lundman B. Changes in sense of coherence in old age - a 5-year follow-up of the Umeå 85+ study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(1):13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudon C, Fortin M, Vanasse A. Cumulative Illness Rating Scale was a reliable and valid index in a family practice context. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Apers S, Luyckx K, Moons P. Unravelling the role of sense of coherence: more research is needed to empirically underpin the construct. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12(6):569–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider G, Driesch G, Kruse A, Wachter M, Nehen HG, Heuft G. What influences self-perception of health in the elderly? The role of objective health condition, subjective well-being and sense of coherence. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;39(3):227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekman I, Fagerberg B, Lundman B. Health-related quality of life and sense of coherence among elderly patients with severe chronic heart failure in comparison with healthy controls. Heart Lung. 2002;31(2):94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Norekvål TM, Fridlund B, Moons P, et al. Sense of coherence—a determinant of quality of life over time in older female acute myocardial infarction survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(5–6):820–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Söderhamn O, Holmgren L. Testing Antonovsky’s sense of coherence (SOC) scale among Swedish physically active older people. Scand J Psychol. 2004;45(3):215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Söderhamn O, Söderhamn U. Sense of coherence and health among home-dwelling older people. Br J Community Nurs. 2010; 15(8):376–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helvik AS, Engedal K, Selbaek G. Change in sense of coherence (SOC) and symptoms of depression among old non-demented persons 12 months after hospitalization. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(2):314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Konttinen H, Haukkala A, Uutela A. Comparing sense of coherence, depressive symptoms and anxiety, and their relationships with health in a population-based study. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(12):2401–2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]