Co-flowering species may undergo interspecific hybridization if they are closely related and share pollinators. However, a series of reproductive barriers between species can prevent interspecific gene flow, making natural hybridization a transient, rare event. Both morphological and molecular data indicated putative natural hybrids between two Silene species from southwest China, with pollen from S. yunnanensis fertilizing ovules of S. asclepiadae. Zhang et al. found that pollen production and viability were significantly lower in putative hybrids than the parental species. The low fecundity of the hybrids and other reproductive barriers between the two species could contribute to species fidelity.

Keywords: Asymmetric hybridization, fecundity, floral phenology, floral traits, pollinator preference, Silene, species integrity

Abstract

Interspecific hybridization is widespread among plants; nevertheless, pre- and post-zygotic isolating mechanisms may maintain species integrity for interfertile species in sympatry despite some gene flow. Interspecific hybridization and potential isolating barriers were evaluated between co-flowering Silene asclepiadea and Silene yunnanensis in an alpine community in southwest China. We investigated morphological and molecular (nuclear microsatellites and chloroplast gene sequence) variation in sympatric populations of S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis. Additionally, we analyzed pollinator behaviour and compared reproductive success between the putative hybrids and their parental species. Both the molecular and morphological data indicate that there were putative natural hybrids in the field, with S. asclepiadae the ovule parent and S. yunnanensis the pollen parent. Bumblebees were the primary visitors to S. asclepiadae and putative hybrids, while butterflies were the primary visitors to S. yunnanensis. Pollen production and viability were significantly lower in putative hybrids than the parental species. The direction of hybridization is quite asymmetric from S. yunnanensis to S. asclepiadea. Protandry combined with later peak flowering of S. yunnanensis, and pollinator preference may have contributed to the asymmetric pattern of hybridization, but putative hybrids were rare. Our results thus suggest that despite gene flow, S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis can maintain species boundaries, perhaps as a result of floral isolation and low fecundity of the hybrids.

Introduction

Hybridization may allow for interspecific gene flow, which at high rates can erode species integrity. Hybridization may be common, and it has been suggested that 25 % of plant species hybridize with other species (Mallet 2005), though the number of well-documented cases of natural hybridization is much less than expected (Brennan et al. 2012). Despite the potential for hybridiation, a series of reproductive barriers may prevent interspecific gene flow (Baack et al. 2015), making natural hybridization a transient, rare event. For example, flowering plants in sympatry may employ different pollinators, or the same pollinator in different flowering periods, or differ in placement of pollen on the same pollinator’s body to reduce interspecific pollen flow (Huang and Shi 2013). The role of pollinator-mediated floral isolation has been questioned given that pollinator inconstant visits may result in interspecific pollen flow, resulting in hybridization and introgression (Armbruster 2014). Therefore, studies on the coexistence of parents and hybrids can help us to understand mechanisms that maintain species boundaries.

The ability of first-generation hybrids to backcross with parental species depends on breeding systems, patterns of pollen transfer among hybrids and the parental species, as well as the viability and fertility of further generation offspring (Burke and Arnold 2001; Grant 1993). Asymmetrical sharing of pollinators between the hybrid and one parental species could contribute to asymmetrical patterns of introgression (Field et al. 2011; Tiffin et al. 2001). However, pollinators are usually generalists which may not distinguish between hybrids and parents, promoting gene exchange between parental species and hybrids (Chung et al. 2005; Haselhorst and Buerkle 2013).

The relative fitness of hybrid progeny is another important factor in determining the fate of hybrids (Burke and Arnold 2001). Hybrids may exhibit a reduction in growth or survival as a result of genetic incompatibilities or the breakup of coadapted gene complexes (Demuth and Wade 2005; Leinonen et al. 2011). Lower fitness of hybrids accompanied by persistent gene flow may result in a stable hybrid zone (Barton and Hewitt 1985). Alternatively, increased fitness in hybrids may allow them to compete successfully with the parents, in extreme cases resulting in the extinction of one of the hybridizing taxa via genetic assimilation (Hegde et al. 2006). Backcrossing between hybrids and parental species allows for introgression (Magnussen and Hauser 2007; Ma et al. 2014). Therefore, in order to assess the role of hybridization in the evolution of interfertile species, it is important to determine the fitness of hybrids as well as behaviour of pollinators towards hybrids and parental species.

Silene (Caryophyllaceae) is a diverse plant genus comprising over 700 species, sensu lato (Greuter 1995; Jenkins and Keller 2011). The genus is widely distributed in Europe, Asia and North America and has colonized a wide range of habitats, ranging from riverbanks to heavy metal polluted soils, and even frozen plateau (Greuter 1995; Jenkins and Keller 2011). Most species are annual to perennial herbaceous plants, and the genus exhibits substantial diversity especially with regard to life cycles, pollination syndromes, and breeding systems (Bernasconi et al. 2009; Greuter 1995; Jenkins and Keller 2011). Silene has become a model system for understanding the evolution of sexual systems and sex chromosomes (Blavet et al. 2012; Demuth et al. 2014; Lengerova et al. 2003), speciation and reproductive isolation (Karrenberg and Favre 2008; Muir et al. 2012), and the effects of nursery pollinators on pollination and seed predation (Kephart et al. 2006). Additionally, studies have investigated interspecific hybridization and isolating mechanisms, primarily focusing on Silene latifolia and its relatives (Brothers and Atwell 2014; Goulson and Jerrim 1997; Karrenberg and Favre 2008; Minder et al. 2007; Montgomery et al. 2010; Prentice 1978; Rahmé et al. 2009).

In China, Silene includes about 110 species, with 67 species endemic, mainly distributed in the northwest and southwest of China (Zhou et al. 2001). Our field survey in southwestern China showed several Silene species generally co-occurred within 1 km2 area. The two native species, Silene yunnanensis and Silene asclepiadea naturally co-occur in Shangri-La county, northwestern Yunnan Province, China. Our initial investigation observed putative hybrids with fruit and flower morphology intermediate between the two species (B. Montgomery and S.-Q. Huang, unpubl. data).

To assess the degree of hybridization and introgression, accurate identification of hybrid genealogies is necessary. Classification of species has been mainly based on morphological characters; however, diagnostic (species-specific) features discriminating between taxa are often limited (Rieseberg and Ellstrand 1993; Vereecken et al. 2010). The use of molecular genetic markers has avoided some of the limitations of morphological characters. Microsatellite (simple sequence repeat, SSR) makers were chosen due to their codominance and ease of identification in studies of hybridization. Molecular markers from organelle genomes (e.g. chloroplasts), which typically have maternal inheritance and low recombination rates, can be used to elucidate the direction of interspecific gene flow and gene introgression that might not be detected by nuclear markers (Bleeker and Hurka 2001). In this study, we evaluated hybridization and introgression in sympatric populations of S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis based on morphological and molecular (SSR and chloroplast gene sequencing) data, and we investigated the roles of pollinator preference and diminished hybrid fecundity in creating pre- and post-zygotic barriers to hybridization, respectively.

Methods

The study species

The study was conducted in a university field station, Shangri-La Alpine Botanical Garden (SABG, 27°54′ N, 99°38′ E) of Yunnan Province, southwest China (see Fang and Huang 2013). The two studied species, S. asclepiadea Franchet and S. yunnanensis Franchet, are closely related within the ‘Cucubaloideae’ group (Zhou et al. 2001). Both species are perennial herbs that co-occur naturally in open alpine meadows mixed with shrubs and near the forest edges in the study site. Geographic ranges overlap, with S. yunnanensis reported from northwest Yunnan Province and S. aspclediadea from Yunnan and two neighboring provinces (eFloras 2008). The two species are protandrous, primarily distinguished by the flower and fruit morphology. Flowers of S. yunnanensis are pink with narrow, long, calyx tubes; its petal-limb length (the portion of the petal above the fused calyx) is much greater than that of S. asclepiadea, which has flowers with dark pink petals and short, broad calyx tubes (Fig. 1). S. asclepiadea flowers earlier (early July) than S. yunnanensis (middle July), but their flowering periods overlap several weeks in SABG, permitting potential interspecific hybridization. Fruit diameters of S. asclepiadea are broader than S. yunnanensis. Dozens of flowering individuals each of the two species were observed in one 50 m × 50 m meadow, suggesting that the population densities of both species were high.

Figure 1.

Flowers and a shared bumblebee pollinator of the two Silene species and a putative hybrid. An apical and side view of S. yunnanensis (A, D), hybrid (B, E) and S. asclepiadea (C, F) flower; and Bombus festivus sucking nectar from flowers of the three taxa (G–I), respectively. Minimum scale at second row = 1 mm.

Morphometric measurement and crossing experiments

To determine if putative hybrids are morphometrically intermediate between the parental species, floral and fruit characters were measured from 30 individuals from both parent species and 11 individuals of putative hybrids, respectively. Five diagnostic morphological traits were measured with a digital caliper, including calyx tube length, calyx tube diameter, corolla diameter, fruit length and fruit diameter. Flowers at the male-phase were measured on live plants in July 2012. All morphological data were analyzed using principal coordinate analysis (PCA) in STATISTICA (StatSoft 2012).

Reciprocal crosses were performed to evaluate the interfertility of S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis. We performed treatments with 10 individuals per species using three or four randomly selected flowers per plant. Flowers of both species were emasculated prior to anthesis and bagged with 1 mm mesh nylon tulle to exclude pollinators. Fresh pollen from each species was transferred manually to the stigma of other species and bagged again until the flower completely withered.

Molecular markers

Leaf material was collected from flowering individuals. A total of 37 S. asclepiadea, 40 S. yunnanensis, and 11 putative hybrids were collected. Samples were placed in individually marked bags and stored in silica gel desiccant.

DNA extraction and SSR analysis: Genomic DNA was extracted from silica-dried leaf material with the Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide method (Doyle and Doyle 1987). Twenty-four microsatellite markers developed by Juillet et al. (2003) and Moccia et al. (2009) were used for genotyping ten individuals to assess polymorphism. Of the 24 primer pairs tested, 14 successfully amplified the target regions, and 8 (SL-eSSR02, SL-eSSR08, SL-eSSR12, SL-eSSR13, SL-eSSR16, SL-eSSR17, SL-eSSR26 and A11) revealed microsatellite polymorphism. Thus, these eight polymorphic microsatellites were used to genotype all of the studied individuals. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a 10 μl volume, containing 25 ng genomic DNA, 0.25 μM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1× buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 U Taq DNA polymerase. Amplifications were conducted in an ABI (Applied Biosystems) Thermocycler. Using the following parameters: 5 min at 95 °C, 35 cycles composed of 50 s denaturing at 94 °C, 50 s annealing at 56 °C, 60 s extension at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were amplified with the 5’ end of one primer of each primer pair labelled with a fluorescent dye, either 6-FAM (SL-eSSR02, SL-eSSR08, SL-eSSR 13, SL-eSSR16) or HEX (SL-eSSR12, SL-eSSR17, SL-eSSR26, A11). Two PCR products of different loci were multiplexed according to the fluorescent dyes and s differences, and separated by capillary gel electrophoresis on an ABI 3730xl automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Microsatellite allele sizes were determined with GeneMapper software 4.0 (Applied Biosystems).

Types of hybrids between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis

A Bayesian algorithm implemented in the software STRUCTURE version 2.3.4 (Hubisz et al. 2009) was used to analyze the species status of S. yunnanensis and S. asclepiadea and to detect interspecific hybrids. We tried different values of K from 1 to 10, and for each K, 5 runs were performed. The appropriate number of clusters was estimated using Evanno’s ΔK parameter (Evanno et al. 2005) using the STRUSTURE HARVESTER programme (Earl and von Holdt 2012). Markov’s chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation parameters were set for a burn-in period of 50,000 and a run length of 106 iterations under the model of population admixture and the assumption that allele frequencies were correlated within populations. We conducted 10 independent runs for testing robustness of the applied model to ensure consistent results.

PCA was used to determine whether hybrids existed between the two species. PCoA was performed on the distance matrices of squared Euclidean distances between all pairs of genotypes by using GENALEX 6.1 (Peakall and Smouse 2006).

Chloroplast haplotypes and gene introgression

We sampled a total of 31 individuals, including 11 putative hybrids and 10 individuals of each parental species. Four non-coding regions of the cpDNA were amplified for two species using the following primer pairs: trnL-e/trnL-f (Taberlet et al. 1991), psbA/trnH (Sang et al. 1997), atpB/rbcL (Chiang et al. 1998) and trnS/trnG (Hamilton 1999). Of the four primer pairs screened, psbA/trnH and atpB/rbcL were found to be the most variable and were therefore selected for genotyping all 31 individuals. Amplification and sequencing followed protocols in Chiang et al. (1998) and Sang et al. (1997), respectively.

The cpDNA sequences were initially aligned using the CLUSTAL_X (Thompson et al. 1997) and then refined manually. All sequences of psbA/trnH and atpB/rbcL have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KT724286-KT724293.

Phenology

We monitored the phenology of S. asclepiadae and S. yunnanensis from 12 July to 10 August, 2012, and we monitored the phenology of hybrids from 29 July to 10 August. For both species and hybrids, we haphazardly selected 12 plants from across several patches and up to 4 stems per plant, as available. We counted the number of previously opened flowers that had already senesced upon initial surveys, then surveyed selected stems of each plant every 3 or 4 days thereafter, counting the number of open flowers. On the final survey date, we counted remaining floral buds. To create cumulative flowering curves, we calculated the total number of open flowers surveyed across all observations, including senesced flowers and remaining buds, and determined the percentage of this total count that had opened by each survey date.

Pollinator observations and insect visitation rate

To measure pollinator visitation rates, we haphazardly selected a patch of flowering plants and counted the numbers of open flowers. We recorded every floral visitor to parental species and putative hybrids each for 20 observation periods. On average, there were 75.0 ± 4.2 (range 42–105) flowers of S. asclepiadea), 56.5 ± 4.6 (26–120) flowers of S. yunnanensis and 48.3 ± 2.8 (28–75) flowers of putative hybrids in one observed patch. We observed floral visitors randomly in 12 clear days from 10.00 a.m. and 18.00 p.m. of local time when pollinators were active with each 30-min per period. Pollinators were defined as visiting a flower when they contacted the stigma or anthers. In addition, we observed 10 h during 20:00–23:00 in 4 clear days to examine moth pollinators, but none were observed visiting these species.

Measurements of pollen and ovules

For each species, 30 flowers were collected just prior to anther dehiscence. The anthers were lacerated and squeezed to release pollen in a 1 ml aniline blue/lactophenol solution. The solution was vortexed, and pollen grains were counted for 10 aliqots, each 10 µl, under a compound microscope. The numbers of uniformly dark stained (viable) and unstained (non-viable) grains were counted, respectively. Ovules were fixed in 70 % ethanol. All ovules were counted under the dissecting microscope. We estimated the ratio of pollen/ovule (P/O) and viable P/O for each flower.

Measurements of fruit and seed production

Fruit set and seed set for naturally pollinated flowers were measured for 30 flowering individuals of both parental species and all putative hybrids. Once flowering ceased and fruits ripened, inflorescences and fruits were counted and one to three fruits per plant were sampled to estimate seed production. Fruit set was defined as the per plant proportion of capsules produced per flower. Seed set was calculated as fully formed seeds divided by the total number of fully developed seeds, and incompletely developed or undeveloped ovules. The average number of seeds per fruit was then calculated for each plant based on seed number in sampled fruits. For each selected capsule, we weighed the seed mass. Fruits exhibiting evidence of seed predation were removed from analysis of percentage seed set and number of seeds.

All measures were compared between parental species and hybrids using one-way analysis of variance using SPSS version 19.0.

Results

Species identities and crossing experiments

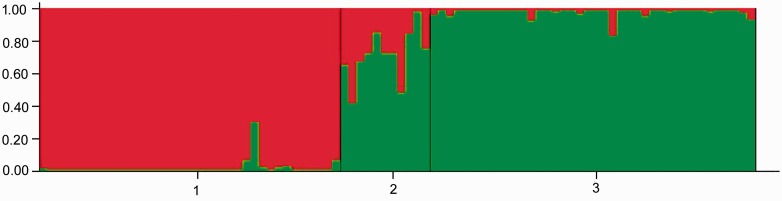

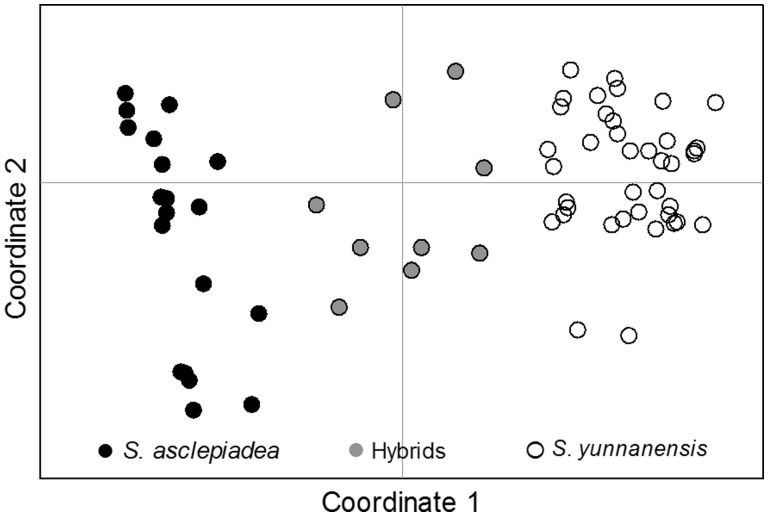

For PCA of morphological measures, principal coordinate axes 1 and 2 explained 34.81 % and 20.96 % of the variation, respectively, and revealed that adult individuals belonged to three separate clusters, corresponding to each parental species and a cluster of hybrids (Fig. 2). The morphological groupings were congruent with the individuals identified as being hybrids by the analysis of microsatellite polymorphisms. Evanno’s ΔK was maximum when K = 2, suggesting assignment of all individuals to two clusters. The analysis indicated a high degree of purity of both parental species, with a membership proportion of the S. asclepiadea population (population 1) in the S. asclepiadea cluster of 97.7 %, and a membership proportion of the S. yunnanensis population (population 3) of 97.9 % in the S. yunnanensis cluster (Fig. 3). The analysis did not resolve the hybrids into a distinct cluster; instead, all hybrid individuals were assigned to either S. asclepiadea population (28.5 %) or the S. yunnanensis population (71.5 %), However, 10 of 11 individuals putatively identified as being hybrids based on morphology had microsatellite genotypes strongly suggestive of contributions from both parent species; this was not the case for most individuals identified as belonging to the parent species based on morphology (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional plot of the PCA showing morphological relatedness between S. asclepiadea, putative hybrids and S. yunnanensis based on 5 morphological measures (calyx tube length, calyx tube diameter, corolla diameter, fruit length and fruit diameter). Axes 1 and 2 explain 34.81 and 20.96 % of the total variance, respectively.

Figure 3.

Bayesian probability of assignment of 88 individuals to a cluster (K = 2) on the basis of multilocus microsatellite genotypes. Populations 1, 2 and 3 are from S. asclepiadea, putative hybrids and S. yunnanensis, respectively.

For PCoA of the SSR data, principal coordinate axes 1 and 2 explained 36.80 and 20.68 % of the variation, respectively, and revealed that all studied individuals belonged to three separate gene pools (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

PCA showing genetic relatedness among the studied individuals. Axes 1 and 2 explain 36.80 and 20.68 % of the total variance, respectively.

Interspecific pollinations were successful and hybrid seeds were obtained from reciprocal crosses between S. yunnanensis and S. asclepiadea. Fruit set was 87.50 % (28/32, i.e. 28 fruits yielded from 32 cross-pollinated flowers) for S. asclepiadea flowers and 87.10 % (27/31) for S. yunnanensis flowers. Five fruits were broken by haymaking for S. asclepiadea and 17 fruits were herbivorized for S. yunnanensis. In S. asclepiadea, about 62.66 % of ovules developed into mature seeds and a fruit produced an average of 53.74 ± 5.12 (mean ± SE) mature seeds (n = 23 fruits). In S. yunnanensis, about 52.42 % of ovules developed into mature seeds and a fruit produced 43.70 ± 5.20 mature seeds (n = 10). Given that higher rates of herbivory in S. yunnanensis mother treatments prevented us from directly contrasting total seed production per flower between the two treatments, we counted the matured seeds (initial) from young fruits before larvae damage.

Genetic diversity, chloroplast haplotypes and gene introgression

The eight microsatellite markers we used were highly polymorphic (2–10 alleles per locus and an average value of 5.1, Table 1). Of 37 S. asclepiadea and 40 S. yunnanensis plants examined, 24 unique alleles were detected in S. yunnanensis but only 6 unique alleles were detected in S. asclepiadea. Of the 24 alleles unique to S. yunnanensis, eight were also present in the putative hybrids. With respect to S. asclepiadea, of six unique alleles, four were present in putative hybrids (Table 1). We did not observe any allele in the putative hybrids that was absent in both parental taxa.

Table 1.

Characterization and utility of eight microsatellite markers for adult individuals of S. yunnanensis (n = 37), S. asclepiadea (n = 40) and putative hybrids (n = 11), respectively collected from Shangri-La Botanical Garden of Yunnan Province. A, number of alleles; n, sample size.

| Locus | A | n | Allele size (bp) S. asclepiadea | Allele size (bp) S. yunnanensis | Allele size (bp) all putative hybrids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL-eSSR02 | 4 | 88 | 200 | 200, 205, 212, 215 | 200 |

| SL-eSSR08 | 8 | 88 | 210, 216, 222, 231 | 210, 219, 222, 225, 228, 231, 237 | 210, 216, 219, 225, 228, 231 |

| SL-eSSR12 | 6 | 88 | 149, 151, 152 | 149, 151, 153, 155, 157 | 152, 155, 157 |

| SL-eSSR13 | 5 | 88 | 182, 190, 196, 200 | 178, 182, 190, 200 | 182, 190 |

| SL-eSSR16 | 2 | 88 | 164, 165 | 164, 165 | 164, 165 |

| SL-eSSR17 | 10 | 88 | 192, 193, 197 | 196, 197, 199, 200, 202, 204, 206, 207 | 192, 193, 196, 204, 206, |

| SL-eSSR26 | 2 | 88 | 160, 198 | 160, 198 | 160, 198 |

| A11 | 4 | 88 | 132, 140, 146, 150 | 132, 146, 150 | 132, 146, 150 |

| Total | 41 | 88 | |||

| Average | 5.1 |

A total of five chloroplast DNA haplotypes were detected (Table 2). S. asclepiadea possessed haplotype H1, H2 and H3, and S. yunnanensis had haplotype H4 and H5. The two species did not share haplotypes with each other. Among the putative hybrids, only one individual had haplotype H1, and all others had haplotype H3.

Table 2.

Variable nucleotide sites and length polymorphisms cpDNA (psbA/trnH and atpB/rbcL) sequences in S. asclepiadea, S. yunnanensis and putative hybrids, respectively. Dashes (–) denote indel.

| Haplotype | Species (numbers) |

psbA/trnH variable sites |

atpB/rbcL variable sites |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 | 77-85 | 140 | 175-178 | 206 | 211 | 219-240 | 266 | 271 | 285 | 340 | 87 | 146-149 | 591-598 | ||

| H1 | S. asclepiadea (1) | – | – – – – – – – – – | – | ATTT | A | C | – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – | G | G | – | G | A | GGTT | CACATAA |

| Hybrid (1) | |||||||||||||||

| H2 | S. asclepiadea (2) | – | TTTGAAAGT | – | ATTT | A | C | – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – | G | G | – | G | A | GGTT | CACATAA |

| H3 | S. asclepiadea (7) | – | TTTGAAAGT | – | ATTT | A | C | – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – | G | G | – | G | A | GGTT | – – – – – – – |

| Hybrid (10) | |||||||||||||||

| H4 | S. yunnanensis (3) | – | TTTGAAAGT | C | – – – – | – | G | ACAAAAGTCTTATTATGTCAAT | A | G | T | – | – | – – – – | – – – – – – – |

| H5 | S. yunnanensis (7) | T | TTTGAAAGT | C | – – – T | A | C | ACAAAAGTCTTATTATGTCAAT | A | A | T | G | – | GGTT | – – – – – – – |

Phenology

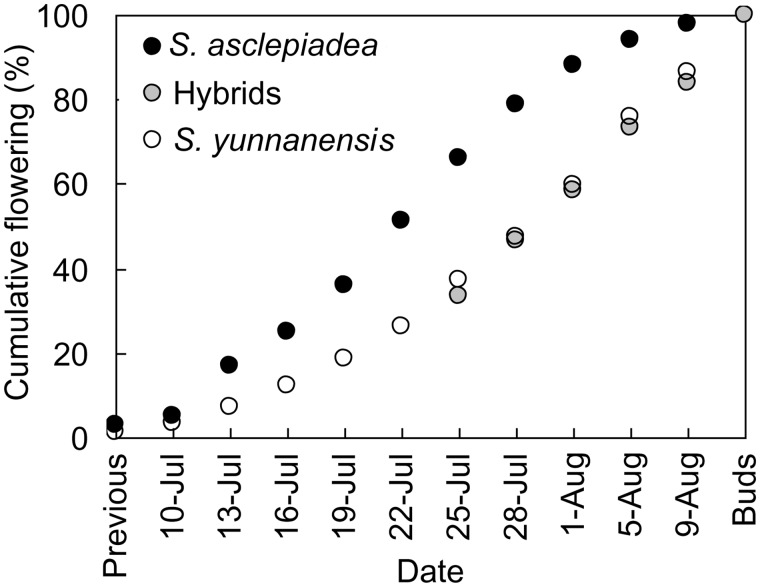

Flowering curves overlapped for both parental species and putative hybrids (Fig. 5). However, cumulative flowering curves for S. asclepiadea were higher than S. yunnanensis for all survey dates, indicating that on average flowering occurred earlier for S. ascplepiadea. The date by which 50 % of flowering was observed for S. asclepiadea was 23 July compared with 2 August for S. yunnanensis and hybrids, a difference of 10 days.

Figure 5.

Cumulative flowering curves for S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis at Shangri-La Botanic Garden, Yunnan Province, China, based on up to 4 flowering stems from each of 12 plants per species, and including flowers already senesced previous to first survey date (previous) and buds remaining on final survey date (Buds). For hybrids, the first survey date was 29 July, and flowers senesced previously are represented as the value for 26 July.

Pollinator observations and insect visitation rate

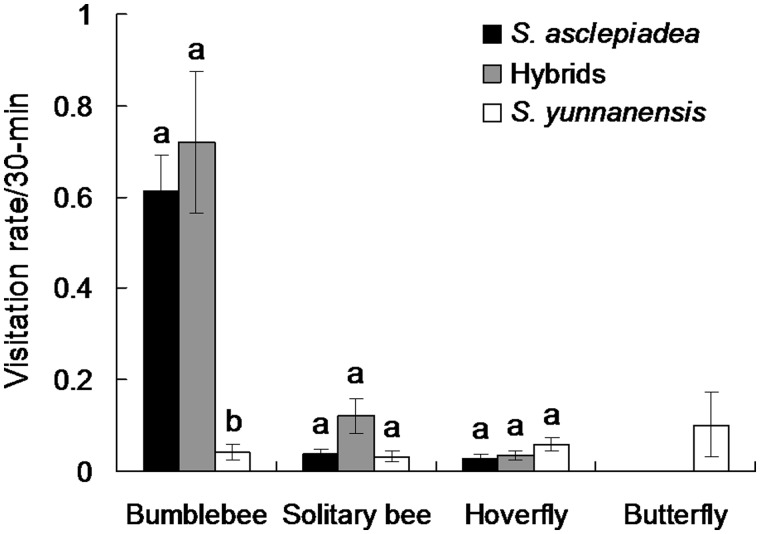

We observed totals of 1500, 1129 and 965 flowers for S. asclepiadea, S. yunnanensis and hybrids, respectively during the 10 h of observations of each group. Bumblebee (Fig. 1) visitation rates were significantly higher to S. asclepiadea and hybrids than to S. yunnanensis (F2, 57 = 13.196, P 0.05) (Fig. 6). Visit rates by solitary bees were significantly higher to hybrids than either parental species (F2, 57 = 4.711, P = 0.013). Hoverfly visitation rates to S. yunnanensis tended to be higher than to S. asclepiadea and hybrids, but rates were not significantly different (F2, 57 = 2.350, P = 0.105). Butterflies made mean 0.101 (± 0.072) visits to S. yunnanensis but did not visit S. asclepiadea or hybrids (Fig. 6). S. asclepiadea and hybrids were visited primarily by bumblebees, accounting for 77.34 and 63.15 % of the floral visits, respectively, while for S. yunnanensis, hoverflies and butterflies were responsible for most visits (36.92 and 30.77 % of visits, respectively).

Figure 6.

Mean number of visits per flower per 30-min observation period by the four main insect visitors to S. asclepiadea, hybrids and S. yunnanensis. Letters above bars represent significant differences among species.

Pollen, abortive pollen, ovule and P/O ratio

Pollen counts between S. asclepiadae and S. yunnanensis were not significantly different but were significantly higher than those of hybrids (F2, 87 = 30.14, P < 0.01); Fig. 7a. Similarly, the number of viable pollen grains per flower was not significantly different between parental species but hybrids produced significantly fewer, <20 % as many viable pollen grains (F2, 87 = 114.41, P < 0.01) (Fig. 7b). The number of ovules per bud was not significantly different among the three flower types (F2, 87 = 1.30, P = 0.278) (Fig. 7c). Because pollen production but not ovule production was reduced in hybrids, both pollen:ovule ratios (F2, 87 = 271.67, P < 0.01) and viable pollen:ovule ratios in hybrids (F2, 87 = 107.60, P < 0.01) were significantly lower compared with the parental species (Fig. 7d).

Figure 7.

Reproductive parameters (means ± SE) for S. asclepiadea, hybrid and S. yunnanensis, including (a) pollen numbers, (b) viable pollen numbers, (c) ovule numbers and (d) viable P/O. Bars with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Fruit/seed set, herbivore ratio and seed mass under natural pollination

Fruit set of open-pollinated flowers averaged 68.56 % (± 2.35 %) in S. asclepiadea and 67.74 % (± 2.97 %) in S. yunnanensis, and did not differ statistically between them (F1, 58 = 0.047, P = 0.829). When compared with S. asclepiadea (19.95 ± 3.69 %), predation of developing fruits was significantly higher (F1, 58 = 49.561, P < 0.01) in S. yunnanensis (63.96 ± 5.04 %). For putative hybrids, the fruit set and percent of fruits exhibiting herbivory were 52.21 % (± 6.58 %) and 17.35 % (± 8.93 %), respectively. We did not compare the differences between putative hybrids and parental species for fruit set or percent of fruit damaged by herbivores because small sample sizes for the hybrids limited statistical power. Seed set between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis was not significantly different, but was significantly higher than in the putative hybrids (F2, 87 = 47.63, P < 0.01) (Fig. 8a). Similarly, the putative hybrids produced significantly fewer seeds per fruit than did S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis (F2, 87 = 48.31, P < 0.01) (Fig. 8b). Average seed mass significantly differed (F2, 87 = 95.92, P < 0.01), with the mass highest in S. asclepiadea, intermediate in S. yunnanensis and lowest in the putative hybrids (Fig. 8c).

Figure 8.

Fecundity measures for S. asclepiadea, putative hybrids and S. yunnanensis in (a) seed set, (b) number of seeds and (c) seed mass under open pollination. Values indicate means ± SE. Bars with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Interspecific hybridization evidence

Previous studies suggest that interspecific hybridization is of relatively frequent occurrence among species of Silene (Karrenberg and Favre 2008; Kruckeberg 1955; Mitchell and Uttal 1969; Minder et al. 2007) and historic hybridization events between moderately distant species were significant in generating several Silene species (Petri et al. 2013). Although several Silene species are sympatric in Asia, particularly in mountain areas in southwest China, this is the first report of natural hybridization. We used eight microsatellites markers and two chloroplast sequences to test the hypothesis of potential hybridization between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis. We found both morphological and molecular evidence that hybridization has occurred between the two species in an area of sympatry. Based on morphological characters, putative hybrids were intermediate to the parental species for four of five morphological quantitative characteristics but similar to S. asclepiadea species for one of the quantitative characteristics. In addition, individuals with intermediate flower and fruit traits were identified by PCA analysis (Fig. 2), suggesting hybridization has occurred. Moreover, all microsatellite alleles at the surveyed loci in the putative hybrids occur in the parental taxa, suggesting that the hybrids are not a well differentiated separate lineage. In addition, three species-diagnostic microsatellites markers for S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis (sl-eSSR08, sl-eSSR12 and sl-eSSR17) were detected in all the putative hybrids (Table 1). Moreover, all putative hybrids had chloroplast psbA/trnH and atpB/rbcL sequences identical with S. asclepiadea, suggesting that S. asclepiadae has been the ovule parent when hybridization has occurred. Subsequent work should investigate other contact zones to determine whether the pattern of asymmetric hybridization is consistent.

Multiple prezygotic and post-zygotic reproductive barriers contribute to isolate potentially interfertile species (Grant 1949; Rieseberg and Willis 2007). Flowering asynchrony or pollinator isolation may act as pre-mating isolating mechanisms. S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis have partially overlapping flowering periods and share some pollinators, suggesting incomplete prezygotic isolation and a possibility of interspecific hybridization. Moreover, our artificial reciprocal crossings between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis confirmed that the two species were cross-compatible and pollen and ovule counts from putative hybrids indicated that hybrids were fertile, suggesting post-zygotic isolation is also incomplete. The present results indicate that the natural hybridization has occurred between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis.

Asymmetric hybridization between S. asclepiadea and S. Yunnanensis

The cpDNA type of 11 putative hybrids matched that of S. asclepiadea (H1 and H3) and the PCA analyses placed the hybrids in an intermediate position between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis, suggesting that S. asclepiadea was the female parent and the paternal parent was S. yunnanensis. If the trend continues, the direction of hybridization should be unidirectional. Asymmetric hybridization is relatively common in plants (Minder et al. 2007; Wu and Campbell 2005; Zha et al. 2010; Muranishi et al. 2013), which can be explained by a variety of causes, including unilateral incompatibility, as well as differences in phenology, pollinator preferences and local abundance of parental species in contact zones (Carney et al. 2000; Muranishi et al. 2013; Zha et al. 2010).

Asymmetric hybridization can be influenced by the local abundance of parental taxa (Burgess et al. 2005; Carney et al. 2000; Lepais et al. 2009), i.e. there is a tendency for locally rare species to provide the female parent in interspecific hybridization. However, the evidence for such an effect is often incomplete. Our field survey found both parental species had similar local abundances in the studied natural community. Thus, the uneven abundance of parental taxa can be ruled out as a cause for asymmetry in this case.

Temporal asynchronism of the flowering contributes to asymmetric hybridization. Both study species are protandrous and peak flowering of S. asclepiadae precedes that of S. yunnanensis by about ten days. Consequently, late in the flowering of S. asclepiadae, there are likely flowers lacking a conspecific pollen source but with male-phase S. yunnanensis in the vicinity. The flowering phenologies of putative hybrids and S. yunnanensis are strikingly similar. This similarity should allow for more opportunities for hybrids to backcross with S. yunnanensis, perhaps contributing to the greater genetic contributions of S. yunnanensis to the hybrids according to the microsatellite data; conversely, more backcrossing with S. yunnanensis may explain why the flower phenology of hybrids and S. yunnanensis are closely matched. Thus, this unilateral pre-zygotic barrier may be attributable to asymmetric hybridization.

Pollinator preference has been implicated as promoting asymmetrical hybridization between species. In animal-pollinated plant species, pollen movement depends on both pollinator behaviour and effectiveness. Thus, selection on floral traits by pollinators is expected to play a key role in the occurrence of asymmetric hybridization (Zha et al. 2010). Our results indicated butterflies were less common pollinators and only visited S. yunnanensis. Moreover, although bumblebees, solitary bees and hoverflies visit both parental species, the hoverflies and solitary bees are likely less effective pollinators. Based on our field investigation, we found that most visits to S. asclepiadea were bumblebees, which showed a stronger preference for S. asclepiadea (Fig. 4), meaning that the visitation pattern would result in conspecific pollen receipt as bumblebees had higher pollinator efficiency than that of hoverflies and solitary bees for most species. Furthermore, pollen grains of S. yunnanensis were observed on the stigmas of S. asclepiadea, but no pollen of S. asclepiadea was on the stigmas of S. yunnanensis for three consecutive years (Gao 2015). Pollinator preference or behaviour resulting in asymmetrical pollen flow has been also observed within the genera Mimulus (Schemske and Bradshaw 1999), Nicotinana (Ippolito et al. 2004), Iris (Matin et al. 2008) and Rhinanthus (Natalis and Wesselingh 2012). These results suggest that pollinator preference may partly explain the asymmetric hybridization between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis.

The maintenance of species boundaries

Silene asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis, two closely related species that coexist in southwest China, provide insight into the mechanisms underlying the maintenance of species boundaries in hybrid zone. Despite the potential for interspecific hybridization between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis, the present study shows that individuals with intermediate morphological phenotypes are rare and many microsatellite alleles were not shared between the two species. Thus, S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis have maintained their species boundaries in sympatry despite the potential for gene exchange via natural hybridization.

Ecological and floral isolation are two important factors in preventing hybridization in plant species. Goulson (2009) proposed the species boundary between Silene dioica and S. latifolia was probably maintained primarily by strong selective forces associated with habitat. There were not apparent differences in either light intensity or relative edaphic conditions between the microhabitats of parental species at the study site (Zhang et al. pers. obs.), but broader survey of the habitats occupied by the parental species would help to determine more definitively whether ecological differentiation contributes to the species boundary. Considering the significant differences in floral morphologies between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis, floral isolation may account for maintenance of their species boundary despite some hybridization occurring. Although some pollinator groups visited putative hybrids and both parental species, bumblebees, the highest visit rates of all pollinators in this study, showed clear preferences for S. asclepiadea and hybrid plants compared with S. yunnanensis, whereas the butterflies visited only S. yunnanensis. Pollinator preference resulting from selection on floral traits by pollinators may contribute to the maintenance of species boundaries in sympatry (Brothers and Atwell 2014). Our findings provide further empirical evidence that floral traits may contribute to maintenance of species boundaries.

Low fitness often occurs in hybrids as a consequence of genomic incompatibility between the parents or disruption of co-adapted complexes (Rieseberg et al. 2003). Relatively low fitness of hybrid progeny, suggesting a reduced competitive ability, may play a significant role in preventing introgression. In the present study, the quantity of viable pollen grains and the viable pollen ratio were significantly lower in putative hybrids than in parents. In addition, we found the seed set of putative hybrids was approximately one-third that of parental species, and the seed mass of putative hybrids was considerably less than that of parent species. Thus, putative hybrids had a lower average relative reproductive performance at early life stages than their parents. Reduced seed production could be due to low pollination success or reduced success in producing seeds. Given that the putative hybrids received high visit rates and that they produced less pollen, it seems more likely that reduced seed production relates to an inability to mature seeds rather than to inadequate pollen receipt. Our analyses do not allow determination of the ancestry of the putative hybrids (e.g. F1, F2, backcross etc.), and it is possible that reproductive output differs among these different generations. Other studies also indicated that hybrids had intermediate or inferior performance compared with parent species (Fritz et al. 2006; Ross et al. 2012). Reduced pollen and seed production observed in putative hybrids may contribute to maintenance of the species boundary of S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis.

Conclusions

Based on the molecular and morphological data, we confirmed that interspecific hybridization occurred between S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis. The direction of hybridization is asymmetric from S. yunnanensis to S. asclepiadea. Phenology, a unilateral pre-zygotic barrier, and pollinator preference may have been responsible for the asymmetric hybridization observed. However, our field investigation indicated S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis were common and the hybrids were rare in the community. Thus, S. asclepiadea and S. yunnanensis can maintain species boundaries despite ongoing hybridization. Floral isolation and low viable pollen and seed production of the putative hybrids contribute to maintenance of species integrity in sympatry. In the present study, our results only focused on early life stages. Future studies including collecting the data about the fitness at later life stages and enlarging sample sizes and studied sites are necessary to further evaluate the mechanisms of species boundaries in spite of inter-hybridization in sympatry.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by a postdoctoral research Foundation grant 2013M540600 to J.-J.Z., a Research Fellowship for International Young Scientists by NSF of China (grant no. 30910362) to B.M. and NSFC (grants no. 31030016, U1402267) to S.-Q.H.

Contributions by the Authors

J.-J.Z. and B.R.M. collected data from the field populations. J.-J.Z. and S.-Q.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed in experimental design, data analysis and commented the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Y.-Z. Xiong, J. Gao, X.-Y. Wang, X.-P. Wang, M. Yang and C.-Q. Liu for their helps in the field investigation and insect identification, and X. Yao providing critical comments on this first article. We thank Z.-D. Fang and staff from Shangri-La Alpine Botanical Garden for logistic support.

Literature Cited

- Armbruster WS. 2014. Floral specialization and angiosperm diversity: phenotypic divergence, fitness trade-offs and realized pollination accuracy. AoB Plants 6:plu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baack E, Melo MC, Rieseberg LH, Ortiz-Barientos D. 2015. The origins of reproductive isolation in plants. New Phytologist 207:968–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH, Hewitt GM. 1985. Analysis of hybrid zones. Annual Review of Ecology and Systmatics 16:113–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi G, Antonovics J, Biere A, Charlesworth D, Delph LF, Filatov D, Giraud T, Hood ME, Marais GAB, McCauley D, Pannell JR, Shykoff JA, Vyskot B, Wolfe LM, Widmer A. 2009. Silene as a model system in ecology and evolution. Heredity 103:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blavet N, Blavet H, Čegan R, Zemp N, Zdanska J, Janoušek B, Hobza R, Widmer A. 2012. Comparative analysis of a plant preudoautosomal region (PRA) in Silene latifolia with the corresponding S. vulgaris autosome. BMC Genomics 13:226.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker W, Hurka H. 2001. Introgressive hybridization in Rorippa (Brassicaceae): gene flow and its consequences in natural and anthropogenic habitats. Molecular Ecology 10:2013–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan AC, Barker D, Hiscock SJ, Abbott RJ. 2012. Molecular genetic and quantitative trait divergence associated with recent homoploid hybrid speciation: a study of Senecio squalidus (Asteraceae). Heredity 108:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers AN, Atwell JW. 2014. The role of pollinator–mediated selection in the divergence of floral traits between two closely related plant species. International Journal of Plant Science 175:287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KS, Morgan M, Deverno L, Husband BC. 2005. Asymmetrical introgression between two Morus species (M. alba, M. rubra) that differ in abundance. Molecular Ecology 14:3471–3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JM, Arnold ML. 2001. Genetics and the fitness of hybrids. Annual Review of Genetics 35:31–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney SE, Gardner KE, Rieseberg LH. 2000. Evolutionary changes over the fifty–year history of a hybrid population of sunflowers (Helianthus). Evolution 54:462–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang TY, Schaal BA, Peng CI. 1998. Universal primers for amplification and sequencing a non–coding spacer between the atpB and rbcL genes of chloroplast DNA. Botanical Bulletin of Academia Sinica 39:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Chung MY, Nason JD, Chung MG. 2005. Patterns of hybridization and population genetic structure in the terrestrial orchids Liparis kumokiri and Liparis makinoana (Orchidaceae) in sympatric populations. Molecular Ecology 14:4389–4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth JP, Wade MJ. 2005. On the theoretical and empirical framework for studying genetic interactions. The American Naturalist 165:524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth JP, Flanagan RJ, Delph LF. 2014. Genetic architecture of isolation between two species of Silene with sex chromosomes and Haldane’s rule. Evolution 68:332–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin 19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Earl DA, Vonholdt BM. 2012. STRUCTURE HARWESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservation Genetics Resources 4:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- eFloras. 2008. Published on the Internet http://www.efloras.org (29 March 2016) Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. 2005. Detecting the number of cluster of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Molecular Ecology 14:2611–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q, Huang S-Q. 2013. A directed network analysis of heterospecific pollen transfer in a biodiverse community. Ecology 94:1176–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field DL, Ayre DJ, Whelan RJ, Young AG. 2011. Patterns of hybridization and asymmetrical gene flow in hybrid zones of the rare Eucalyptus aggregata and common E. rubida. Heredity 106:841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz RS, Hochwender CG, Albrectson BR, Czesak ME. 2006. Fitness and genetic architecture of parent and hybrid willows in common gardens. Evolution 60:1215–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. 2015. On dynamics of heterospecific pollen transfer among sympatric plants in an alpine meadow. PhD thesis, Wuhan University, China.

- Goulson D. 2009. Evaluating the role of ecological isolation in maintaining the species boundary between Silene dioica and S. latifolia. Plant Ecology 205:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Goulson D, Jerrim K. 1997. Maintenance of the species boundary between Silene dioica and S. latifolia (red and white campion). Oikos 79:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Grant V. 1949. Pollination systems as isolating mechanisms in angiosperms. Evolution 7:51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant V. 1993. Effects of hybridization and selection on floral isolation. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science, United States of America 90:990–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greuter W. 1995. Silene (Caryophyllaceae) in Greece: a subgeneric and sectional classification. Taxon 44:543–581. [Google Scholar]

- Haselhorst MSH, Buerkle CA. 2013. Population genetic structure of Picea engelmannii, P.glauca and their previously unrecognized hybrids in the central Rocky Mountains. Tree Genetics and Genomes 9:669–681. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde SG, Nason JD, Clegg JM, Ellstrand NC. 2006. The evolution of California’s wild radish has resulted in the extinction of its progenitors. Evolution 60:1187–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton MB. 1999. Four primer pairs for the amplification of chloroplast intergenic regions with intraspecific variation. Molecular Ecology 8:521–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S-Q, Shi X-Q. 2013. Floral isolation in Pedicularis: how do congeners with shared pollinators minimize reproductive interference? New Phytologist 199:858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubisz MJ, Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. 2009. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Molecular Ecology Resources 9:1322–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito A, Fernandes GW, Holtsford TP. 2004. Pollinator preferences for Nicotinan alata, N. forgetiana and their F1 hybrids. Evolution 58:2634–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Keller SR. 2011. A phylogenetic comparative study of preadaptation for invasiveness in the genus Silene (Caryophyllaceae). Biology Invasions 13:1471–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Juillet N, Freymond H, Degen L, Goudet J. 2003. Isolation and characterization of higely polymorphic microsatellite loci in the bladder campion, Silene vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae). Molecular Ecology Notes 3:358–359. [Google Scholar]

- Karrenberg S, Favre A. 2008. Genetic and ecological differentiation in the hybridizing campions Silene diocia and S. latifolia. Evolution 62:763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kephart S, Reynolds RJ, Rutter MT, Fenster CB, Dudash MR. 2006. Pollination and seed predation by moths on Silene and allied Caryophyllaceae: evaluating a model system to study the evolution of mutualisms. New Phytologist 169:667–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruckeberg AR. 1955. Interspecific hybridizations of Silene. American Journal of Botany 42:373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen PH, Remington DL, Savolainen O. 2011. Local adaptation, phenotypic differentiation, and hybrid fitness in diverged natural populations of Arabidopsis lyrata. Evolution 65:90–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengerova MR, Moore C, Grant SR, Vyskot B. 2003. The sex chromosomes of Silene latifolia revisited and revised. Genetics 165:935–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepais O, Petit R, Guichoux E, Lavabre JE, Alberto F, Kremer A, Gerber S. 2009. Species relative abundance and direction of introgression in oaks. Molecular Ecology 18:2228–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YP, Xie WJ, Tian XL, Sun WB, Wu ZK, Milne R. 2014. Unidirectional hybridization and reproductive barriers between two heterostylous primrose species in northwest Yunnan, China. Annals of Botany 113:763–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen LS, Hauser TP. 2007. Hybrids between cultivated and wild carrots in natural populations in Denmark. Heredity 99:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet J. 2005. Hybridization as an invasion of the genome. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20:229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NH Sapir Y Arnold ML.. 2008. The genetic architecture of reproductive isolation in Louisinan irises: pollination syndromes and pollinator preferences. Evolution 62:740–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minder AM, Rothenbuehler C, Widmer A. 2007. Genetic structure of hybrid zones between Silene latifolia and Silene dioica (Caryophyllaceae): evidence for introgressive hybridization. Molecular Ecology 16:2504–2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RS, Uttal LJ. 1969. Natural hybridization in Virginia Silene (Caryopyllaceae). Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 96:544–549. [Google Scholar]

- Moccia MD, Oger–Desfeux C, Marais GAB, Widmer A. 2009. A white campion (Silene latifolia) expressed sequence tag (EST) library: annotation, EST–SSR characterization, transferability, and utility for comparative mapping. BMC Genomics 10:243.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BR, Soper DM, Delph LF. 2010. Asymmetrical conspecific seed-siring advantage between Silene latifolia and S. dioica. Annals of Botany 105:595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir G, Dixon CJ, Harper AL, Filatov DA. 2012. Dynamics of drift, gene flow, and selection during speciation in Silene. Evolution 66:1447–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranishi S, Tamaki I, Setsuko S, Tomaru N. 2013. Asymmetric introgression between Magnolia stellata and M. salicifolia at a site where the two species grow sympatrically. Tree Genetics & Genomes 9:1005–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Natalis LC, Wesselingh RA. 2012. Shared pollinators and pollen transfer dynamics in two hybridizing species, Rhinanthus minor and R. angustifolius. Oecologia 170:709–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R, Smouse PE. 2006. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology Notes 6:288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri A, Pfeil BE, Oxelman B. 2013. Introgressive hybridization between anciently diverged lineages of Silene (Caryophyllaceae). PLoS One 8:e67729.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice HC. 1978. Experimental taxonomy of Silene section Elisanth (Caryophyllaceae): crossing experiments. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 77:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmé J, Widmer A, Karrenberg S. 2009. Pollen competition as an asymmetric reproductive barrier between two closely related Silene species. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 22:1937–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Ellstrand NC. 1993. What can molecular and morphological markers tell us about plant hybridization? Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 12:213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Raymond O, Rosenthal DM, et al. 2003. Major ecological transitions in wild sunflowers facilitated by hybridization. Science 301:1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Willis JH. 2007. Plant speciation. Science 317:910–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RI, Agren JA, Pannell JR. 2012. Exogenous selection shapes germination behavior and seedling traits of populations at different altitudes in a Senecio hybrid zone. Annals of Botany 110:1439–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang T, Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF. 1997. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae). American Journal of Botany 84:1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemske DW, Bradshaw HD. 1999. Pollinator preference and the evolution of floral traits in monkeyflowers (Mimulus). Proceeding of the National Academy of Science United States of America 96:11910–11915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StatSoft I. 2012. STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 11. Website: http://www.statsoft.com.

- Taberlet P, Gielly L, Pautou G, Bouvet J. 1991. Universal primers for amplification of three non–coding regions of chloroplast DNA. Plant Molecular Biology 17:1105–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The CLUSTAL_ X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research 24:4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin P, Olson MS, Moyle LC. 2001. Asymmetrical crossing barriers in angiosperms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 268:861–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken NJ, Cozzolino S, Schiestl FP. 2010. Hybrid floral scent novelty drives pollinator shift in sexually deceptive orchids. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10:103.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CA, Campbell DR. 2005. Cytoplasmic and nuclear markers reveal contrasting patterns of spatial genetic structure in a natural Ipomopsis hybrid zone. Molecular Ecology 14:781–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha HG, Miline RI, Sun H. 2010. Asymmetric hybridization in Rhododendron agastum: a hybrid taxon comprising mainly F1s in Yunnan, China. Annals of Botany 105:89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Wu Z, Lidua M, Oxelman B. 2001. Silene. Flora of China 6:66–100. [Google Scholar]