Abstract

Background and purpose

Knee arthroscopy is commonly performed to treat degenerative knee disease symptoms and traumatic meniscal tears. We evaluated whether the recent high-quality randomized control trials not favoring arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee disease affected the procedure incidence and trends in Finland and Sweden.

Patients and methods

We conducted a bi-national registry-based study including all adult (aged ≥18 years) inpatient and outpatient arthroscopic surgeries performed for degenerative knee disease (osteoarthritis (OA) and degenerative meniscal tears) and traumatic meniscal tears in Finland between 1997 and 2012, and in Sweden between 2001 and 2012.

Results

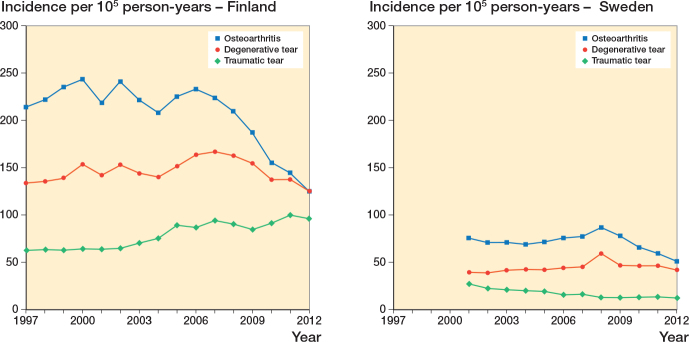

In Finland, the annual number of operations was 16,389 in 1997, reached 20,432 in 2007, and declined to 15,018 in 2012. In Sweden, the number of operations was 9,944 in 2001, reached 11,711 in 2008, and declined to 8,114 in 2012. The knee arthroscopy incidence for OA was 124 per 105 person-years in 2012 in Finland and it was 51 in Sweden. The incidence of knee arthroscopies for meniscal tears coded as traumatic steadily increased in Finland from 64 per 105 person-years in 1997 to 97 per 105 person-years in 2012, but not in Sweden.

Interpretation

The incidence of arthroscopies for degenerative knee disease declined after 2008 in both countries. Remarkably, the incidence of arthroscopy for degenerative knee disease and traumatic meniscal tears is 2 to 4 times higher in Finland than in Sweden. Efficient implementation of new high-quality evidence in clinical practice could reduce the number of ineffective surgeries.

Degenerative knee disease produces a variety of symptoms, clinical findings, and tissue abnormalities, eventually leading to knee osteoarthritis (OA). Nonoperative treatment of degenerative knee disease is recommended in guidelines, but arthroscopy is widely used (Kim et al. 2011, Nelson et al. 2014). Arthroscopic treatment includes debridement (lavage, smoothening, and removal of loose articular cartilage fragments), treatment of cartilage lesions, and resection of meniscal lesions (Felson 2010). Meniscal repair is preferred for acute traumatic tears of the meniscus (Sgaglione 2005). However, it is often difficult to distinguish between degenerative and traumatic meniscal tears. In older individuals and in patients with knee OA, meniscal tears are often degenerative and their prevalence increases with age (Curl et al. 1997, Metcalf and Barrett 2004, Englund et al. 2008). In younger patients, traumatic meniscal tears usually result from acute knee injury and are often associated with tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (Poehling et al. 1990).

The practice of knee arthroscopy is in turmoil. In 2002, a pivotal randomized and placebo- (surgery) controlled trial found that arthroscopic debridement or lavage is no better than a sham procedure for treating knee OA (Moseley et al. 2002). This finding was later corroborated by Kirkley et al. (2008). This evidence led to recommendations to avoid knee arthroscopy procedures for patients with a primary diagnosis of knee OA (Conaghan et al. 2008, Richmond et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2010). The recommendations, however, provided the option of knee arthroscopy in patients with signs and symptoms of a torn meniscus (Conaghan et al. 2008, Richmond et al. 2009) and for patients with low-grade OA (Zhang et al. 2010).

Previous reports regarding the trends in a number of knee arthroscopic procedures indicate a reduced incidence of arthroscopies for knee OA, and a steady increase in the number of arthroscopic meniscus surgeries (Hawker et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2011, Abrams et al. 2013). In the UK, the incidence of arthroscopic meniscal resections more than doubled from 2000 to 2012 in patients over 60 years of age (Lazic et al. 2014). Similarly, in Denmark the number of meniscal procedures in patients aged 35 years or more increased during the period 2000–2011 (Thorlund et al. 2014).

In this bi-national registry-based study involving the entire populations of Finland and Sweden, we assessed the numbers and incidence trends of arthroscopic knee procedures for degenerative knee disease and meniscal tears in Finland (between 1997 and 2012) and in Sweden (between 2001 and 2012).

Patients and methods

We used the Finnish and Swedish National Hospital Discharge Registers (NHDRs) to evaluate the incidence of and trends in arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee disease and meniscal tears. All patients 18 years of age or older in both NHDRs were included. In Finland, data were available from January 1, 1997 through December 31, 2012, and in Sweden, data were available from January 1, 2001 through December 31, 2012. The Finnish and Swedish NHDRs provide excellent databases for epidemiological studies, as they contain data on age, sex, and domicile of the subject; length of hospital stay; primary and secondary diagnoses; and operations performed during the hospital stay. The data collected by the NHDR are mandatory for all hospitals to provide—including private, public, and other institutions—for both inpatient and outpatient settings. Although coverage and accuracy of both NHDRs is good (Ludvigsson et al. 2011, Sund 2012, Huttunen et al. 2014), an internal validity control of the data revealed that 2 hospitals in Stockholm, Sweden had performed approximately 1,800 knee arthroscopies annually for degenerative knee disease or meniscal tears in recent years, whereas the number had doubled in 2012, raising suspicion of double-coding of procedures (Socialstyrelsen 2009, Socialstyrelsen 2014). Thus, due to the potential problems with internal validity, we excluded these 2 hospitals in Stockholm from the analysis with regard to the whole study period (2001—2012).

The main outcome variable was the number of knee arthroscopies performed for degenerative knee disease (including OA and degenerative meniscal tears) and traumatic meniscal tears (Table 1). For diagnoses, the ICD-10 coding system was used, and for procedural coding, we used the national NCSP procedural codes maintained by NOMESCO (Socialstyrelsen 2004, Lehtonen et al. THL 2013). These coding systems allow physicians to set multiple diagnoses. We categorized knee arthroscopies based on the diagnosis and procedural codes as follows: (a) Osteoarthritis, (b) Degenerative meniscal tear, (c) Traumatic meniscal tear undergoing debridement/resection, and (d) Traumatic meniscal tear undergoing repair (Table 1). The code M23* (meniscal derangement due to old tear or injury or other meniscal derangements) was used for degenerative meniscal tears, and the code S83.2 (acute meniscal tear) was used for traumatic tears. In cases of multiple knee diagnoses for the same surgical procedure (e.g. a first diagnosis of M23* and a second of M17*, or a first diagnosis of M23* and a second of S83.2), the procedure was categorized according to the more degenerative diagnosis (e.g. M17 and M23 was defined as M17, and M23 and S83 as M23).

Table 1.

ICD-10 diagnosis and NCSP procedural codes included in Finland and in Sweden

| ICD-10 diagnoses | Procedural codes in Finnish coding system (Lehtonen et al. THL 2013) | Procedural codes in Swedish coding system (Socialstyrelsen 2004) |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis | ||

| M17.0 Primary gonarthrosis, bilateral | NGA30 Arthroscopic exploration of knee joint | NGA11 Arthroscopic exploration of knee joint |

| M17.1 Gonarthrosis, bilateral | NGD05 Arthroscopic partial resection of menisci | NGD11 Arthroscopic partial resection of menisci |

| M17.3 Other post-traumatic gonarthrosis | NGF25 Arthroscopic debridement of knee joint | NGF31 Arthroscopic debridement of knee joint |

| M17.9 Gonarthrosis, unspecified | NGF35 Arthroscopic partial excision of joint cartilage of knee | NGF91 Partial excision of joint cartilage of knee |

| M22.4 Chondromalacia patellae | ||

| Degenerative meniscal tear | ||

| M23.2 Derangement of meniscus due to old tear or injury | NGA30 Arthroscopic exploration of knee joint | NGA11 Arthroscopic exploration of knee joint |

| M23.3 Other meniscal derangements | NGD05 Arthroscopic partial resection of menisci | NGD11 Arthroscopic partial resection of menisci |

| M23.4 Loose body in knee | NGF25 Arthroscopic debridement of knee joint | NGF31 Arthroscopic debridement of knee joint |

| M23.8 Other internal derangements of knee | NGF35 Arthroscopic partial excision of joint cartilage of knee | NGF91 Partial excision of joint cartilage of knee |

| M23.9 Internal derangement of knee, unspecified | ||

| Traumatic meniscal tear, debridement | ||

| S83.2 Tear of meniscus, current | NGA30 Arthroscopic exploration of knee joint | NGA11 Arthroscopic exploration of knee joint |

| NGD05 Arthroscopic partial resection of menisci | NGD11 Arthroscopic partial resection of menisci | |

| NGF25 Arthroscopic debridement of knee joint | NGF31 Arthroscopic debridement of knee joint | |

| NGF35 Arthroscopic partial excision of joint cartilage of knee | NGF91 Partial excision of joint cartilage of knee | |

| Traumatic meniscal tear, repair | ||

| S83.2 Tear of meniscus, current | NDG25 re-insertion of meniscus | NGD21 re-insertion of meniscus |

Statistics

To compute the incidence of knee arthroscopy, the age- and sex-specific annual mid-population was obtained from the Finnish and Swedish Official Statistics, which yield data from an electronic national population registry (Official Statistics of Finland 2015, Statistics Sweden 2015). The incidence of knee arthroscopy (per 105 person-years) was based on the results of the entire adult population (≥18 years) of Finland and Sweden rather than cohort- or sample-based estimates, and therefore confidence intervals were not calculated. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0.

Ethics

We obtained the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of Finland (entry no. THL 89/5.0500/2012) and Sweden (The Regional Ethics Committee of Stockholm, entry no. 2013/ 5:6).

Results

During the study period in Finland, from 1997 through 2012, a total of 287,225 knee arthroscopies to treat degenerative knee disease (n = 233,375) or traumatic meniscal tears (n = 53,850) were identified in the adult population (4.0–4.3 million). The total number of knee arthroscopies for degenerative knee disease or traumatic meniscal tears in 1997 was 16,389, and in 2007 the number peaked to 20,432. Thereafter, the number of arthroscopies declined and was 15,018 in 2012. The mean age of male and female patients was 47 and 52 years, and it did not change markedly during the study period. In Sweden with an adult population of 7.1–7.6 million, the total number of arthroscopies performed for degenerative knee disease or traumatic meniscal tears from 2001 through 2012 was 115,907 (100,469 and 15,438, respectively). The number of operations in 2001 was 9,944, and the highest number of arthroscopies (11,711) was performed in 2008. The number of arthroscopies then declined to 8,114 in 2012 (Figure, Tables 2 and 3). In general, the incidence rates of knee arthroscopy were markedly lower in Sweden than in Finland.

Incidence of knee arthroscopy for osteoarthritis, degenerative meniscal tears, and traumatic meniscal tears in Finland from 1997 to 2012 (left panel) and in Sweden from 2001 to 2012 (right panel), per 105 person-years. 2 hospitals in Sweden were excluded due to suspected double-coding.

Table 2.

Incidence of knee arthroscopy (per 105 person-years) and mean age of patients for osteoarthritis, degenerative meniscal tear, and traumatic meniscal tear (debridement and repair) in Finland from 1997 to 2012

| Year | Osteoarthritis |

Degenerative meniscus |

Traumatic meniscus (debridement) |

Traumatic meniscus (repair) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Mean age | Incidence | Mean age | Incidence | Mean age | Incidence | Mean age | |

| 1997 | 214 | 52 | 134 | 49 | 63 | 42 | 1.2 | 44 |

| 1998 | 222 | 53 | 136 | 50 | 64 | 42 | 1.4 | 40 |

| 1999 | 235 | 53 | 139 | 50 | 63 | 43 | 1.9 | 39 |

| 2000 | 244 | 53 | 154 | 51 | 65 | 43 | 2.0 | 43 |

| 2001 | 218 | 54 | 142 | 51 | 64 | 43 | 1.8 | 37 |

| 2002 | 240 | 54 | 153 | 51 | 65 | 43 | 1.9 | 38 |

| 2003 | 221 | 54 | 144 | 52 | 71 | 44 | 1.6 | 39 |

| 2004 | 208 | 54 | 140 | 52 | 76 | 44 | 1.7 | 41 |

| 2005 | 225 | 54 | 151 | 52 | 90 | 45 | 1.9 | 39 |

| 2006 | 233 | 55 | 164 | 53 | 87 | 45 | 2.0 | 39 |

| 2007 | 224 | 55 | 167 | 53 | 95 | 45 | 1.9 | 42 |

| 2008 | 210 | 55 | 163 | 53 | 91 | 45 | 1.3 | 38 |

| 2009 | 187 | 55 | 155 | 53 | 85 | 45 | 1.5 | 40 |

| 2010 | 155 | 54 | 138 | 52 | 92 | 46 | 1.7 | 38 |

| 2011 | 145 | 54 | 138 | 53 | 101 | 46 | 2.2 | 37 |

| 2012 | 124 | 54 | 125 | 52 | 97 | 46 | 2.1 | 40 |

Table 3.

Incidence of knee arthroscopy (per 105 person-years) and mean age of patients for osteoarthritis, degenerative meniscal tear, and traumatic meniscal tear (debridement and repair) in Sweden from 2001 to 2012

| Year | Osteoarthritis |

Degenerative meniscus |

Traumatic meniscus (debridement) |

Traumatic meniscus (repair) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Mean age | Incidence | Mean age | Incidence | Mean age | Incidence | Mean age | |

| 2001 | 76 | 52 | 40 | 46 | 27 | 39 | 0.4 | 28 |

| 2002 | 71 | 52 | 39 | 47 | 22 | 39 | 0.4 | 30 |

| 2003 | 71 | 51 | 41 | 46 | 21 | 38 | 0.4 | 31 |

| 2004 | 69 | 52 | 43 | 46 | 20 | 38 | 0.4 | 31 |

| 2005 | 72 | 52 | 42 | 46 | 20 | 38 | 0.8 | 28 |

| 2006 | 76 | 53 | 44 | 47 | 16 | 38 | 0.7 | 29 |

| 2007 | 77 | 53 | 45 | 47 | 16 | 38 | 0.5 | 31 |

| 2008 | 87 | 53 | 59 | 48 | 13 | 37 | 0.5 | 31 |

| 2009 | 78 | 53 | 47 | 47 | 13 | 36 | 0.7 | 30 |

| 2010 | 66 | 52 | 46 | 46 | 13 | 36 | 0.8 | 30 |

| 2011 | 59 | 52 | 46 | 46 | 14 | 35 | 0.8 | 29 |

| 2012 | 51 | 53 | 42 | 47 | 13 | 35 | 0.7 | 30 |

I Finland, the incidence of knee arthroscopy for OA increased to 240 per 105 person-years in 2002 and then decreased by 48% to 124 per 105 person-years in 2012. In Sweden, the incidence of knee arthroscopy for OA increased to 87 per 105 person-years in 2008, and then decreased by 41% to 51 per 105 person-years in 2012. The mean age of OA patients was 54 years in Finland and 52 years in Sweden.

The incidence of arthroscopy for degenerative meniscal tears in Finland increased slightly from 1997 to 2007 (incidence 167 per 105 person-years in 2007) and then declined to 125 per 105 person-years in 2012. The incidence of arthroscopic debridement for traumatic meniscal tears increased by 55% during the study period from 63 per 105 in 1997 to 97 per 105 in 2012. In both groups of meniscal tears in Finland, the mean age increased slightly during the study period from 49 years in 1997 to 52 years in 2012 for those with degenerative meniscal tears and from 42 years in 1997 to 46 years in 2012 for those with traumatic meniscal tears undergoing debridement.

In Sweden, the incidence of arthroscopy for degenerative meniscal tears remained practically unaltered (39 to 46 per 105 person-years) during the study period, except in 2008 when the incidence was 59 per 105 person-years. The mean age of these patients did not change either (46 years in 2001 and 47 years in 2012). The incidence of traumatic tears undergoing debridement decreased during the study period from 27 per 105 person-years in 2001 to 13 per 105 person-years in 2012. Unlike in Finland, the mean age of patients with traumatic tears undergoing debridement decreased in Sweden during the study period from 39 years in 2001 to 35 years in 2012.

The incidence of meniscal repair for traumatic meniscal tears remained low and unaltered during the study period in both countries, ranging from 2.2 to 1.3 per 105 person-years in Finland and from 0.4 to 0.8 per 105 person-years in Sweden. The mean age of patients undergoing meniscal repair remained the same during the study period—38 years in Finland and 30 years in Sweden.

Discussion

The 2 main findings of our bi-nationwide study conducted in Finland and Sweden were that the incidence of arthroscopy for knee OA has decreased in both countries (in Finland since 2006 and in Sweden since 2008), and that the overall incidence of knee arthroscopy due to degenerative knee disease and traumatic meniscal tears was almost 4 times higher in Finland than in Sweden. In Finland, the incidence of arthroscopy for degenerative meniscal tears has decreased since 2007, but there has been a simultaneous increase in debridement surgery for meniscal lesions coded as traumatic meniscal tears. Additionally, the mean age of these patients has increased. In Sweden, the incidence of debridement arthroscopy for both degenerative meniscal injuries and injuries coded as traumatic has been practically unchanged and in contrast to Finland, the mean age of patients with traumatic tear has decreased.

Previous studies have found similar changes in the incidence of knee arthroscopy. A 49% overall increase in knee arthroscopies in the USA between 1996 and 2006 has been reported (Kim et al. 2011); the incidence of arthroscopy for OA decreased while the incidence of meniscal tears increased. Potts et al. (2012) reported a decrease in arthroscopy for OA according to the American Board Exam when comparing the results in 1999 with those in 2009. A report from England and Ontario, Canada, showed that the number of knee arthroscopies for OA had decreased from 1993 to 2004, while the number of knee arthroscopies for meniscal tears had increased (Hawker et al. 2008). This change in practice was evident after the publication of highly cited articles demonstrating a lack of efficacy of knee arthroscopy in OA (Moseley et al. 2002, Kirkley et al. 2008). Accordingly, the current treatment guidelines stand against knee arthroscopy for the treatment of established OA (Zhang et al. 2010, Brown 2013). Scientific evidence demonstrating the lack of efficacy of arthroscopic treatment for knee OA may also be the main cause of the decline in surgery rates in Finland and Sweden.

Although the incidence of knee arthroscopy for OA has decreased worldwide, the incidence of arthroscopy for meniscal tears has increased. Most recently, Thorlund et al. (2014) from Denmark reported that the incidence of meniscus surgery had doubled from 2000 to 2011 (the annual incidence increased from 164 to 312 per 105 person-years). Furthermore, in their other study the increase in incidence was seen especially in the private sector (Hare et al. 2015). In addition, quite remarkably, the incidence increased 3-fold in patients over 55 years of age (Thorlund et al. 2014). These findings are consistent with ours, as the data were extracted from a National Patient Register in a Scandinavian country similar to those in the current bi-national study. Moreover, Lazic et al. (2014) reported a similar increase in meniscus surgery for patients over 65 years of age in the UK between 2000 and 2012. In the present study, the incidence of surgery for degenerative meniscal tears increased in Finland from 1997 to 2007, but not in Sweden. Although the incidence in Finland has declined since 2007, the incidence of knee arthroscopy for degenerative meniscal tears was still 3 times higher than that in Sweden in 2012 and the patients were markedly older in Finland than in Sweden.

There is no clear explanation for the difference in the incidence of knee arthroscopy between Finland and Sweden. It is not likely that the difference in these rather similar Scandinavian countries could be fully explained by a different incidence of knee degeneration or trauma. Cultural issues may also play a role. Geographical variations in surgical procedures result mainly from differences in physician beliefs about the indications for surgery, and the extent to which patient preferences are incorporated into treatment decisions, while a smaller degree of variation in regional surgery rates is due to differences in illness burden, diagnostic practices, and patient attitudes (Birkmeyer et al. 2013, Hare et al. 2015). Financial incentives also influence the practice patterns of physicians (Mitchell 2010, Hare et al. 2015). In addition, the number of knee MRIs and knee arthroscopies performed appears to be correlated (Hare et al. 2015). A recent Danish study revealed that the incidence of meniscus surgery in Denmark is twice as high as that in Finland, and 6 times higher than that in Sweden (Thorlund et al. 2014). The great differences in the numbers of arthroscopic debridement procedures performed in these Scandinavian countries can be compared to the variations in the incidence rates of knee arthroplasty. A recent study showed that the incidence of primary total knee replacements was 180 per 105 person-years in Finland, 110 per 105 person-years in Sweden, and 140 per 105 person-years in Denmark (Kurtz et al. 2011).

While the incidence of arthroscopy for degenerative meniscal tears began to decline in Finland in 2007, there was an increase in the incidence of arthroscopy for meniscal tears, coded as traumatic but undergoing debridement. It is noteworthy that 44% of all meniscal tears were coded as traumatic in Finland, as compared to 24% in Sweden. In addition to the above-mentioned reasons for the different incidences of procedures between these countries, there may be differences in coding. A change in coding for meniscal tears may have occurred in Finland, because the mean age of patients with meniscal tears coded as traumatic increased from 42 to 46 years. There was no change in either the incidence or the mean age, however, in Sweden. A change in coding was put forward to explain the increase in meniscus surgery in the USA between 1996 and 2006 (Kim et al. 2011). Since 2004, Medicare has not paid for knee arthroscopy performed to treat OA. Thus, for insurance authorization, many cases that would have had a diagnostic code for knee OA may have been coded more recently as meniscal tears because many knees with OA also show degenerative meniscal tears (Englund et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2011). In Finland, part of these procedures are financed by insurance companies, and treated in private hospitals, but only if the tear is coded as traumatic. This may cause orthopedic surgeons in Finland to more frequently code meniscal tears as traumatic rather than degenerative. Differentiating whether a tear is traumatic or non-traumatic (degenerative) is often clinically difficult, and there may be variations between surgeons and patients regarding interpretation of the etiology of the knee complaints. In addition, some patients with traumatic meniscal tears could still seek medical advice after a period of nonoperative treatment, leading to a tear being coded old (degenerative). Also, some patients with degenerative tears have an acute/sudden onset of symptoms with or without a clear knee injury, and these are therefore coded as traumatic (Drosos and Pozo 2004). Based on the current literature, only 5–15% of all treated meniscal tears are traumatic (Metcalf and Barrett 2004, Christoforakis et al. 2005, Camanho et al. 2006), and according to a report from the USA, 75% of patients undergoing meniscus repair are under 35 years of age (Abrams et al. 2013). The incidence of meniscus repairs in our study remained low and unchanged during the study period in both Finland and Sweden. These facts argue against a true change in the incidence of traumatic meniscal tears—and rather for a change in coding.

One strength of our study is that the results reflect actual treatment policies and practices of Finnish and Swedish orthopedic surgeons, and that we used true population-based bi-nationwide data. The coverage of the study can be considered to be excellent, as medical treatment is equally available to everyone in Finland and Sweden. The NHDRs used in Finland and Sweden have excellent coverage and accuracy (Mattila et al. 2008, Ludvigsson et al. 2011). Thus, we feel that the declining trend in the proportion of operative treatments for degenerative knee disease represent the real current opinion of Finnish and Swedish physicians treating these disorders.

A limitation of our study was that 2 large hospitals in Sweden had to be excluded from the analysis due to suspicion of double-coding of operations in 2012 in the SNHDR (Socialstyrelsen 2009, Socialstyrelsen 2014). We excluded these hospitals for the entire study period between 2001 and 2012, so our results may underestimate the real incidence of knee arthroscopy in Sweden by about 15%. In addition, although our decision to differentiate the incidence numbers as those with knee OA, those with degenerative meniscal tears, those with traumatic tears with debridement, and those with traumatic tears with repair is consistent with clinical practice; it may not reflect the reality behind the registry data, as it is not possible to have information on more detailed arthroscopic findings or individual patient history. Besides, it is often difficult to make a diagnosis; the coding may also be influenced by other factors. As discussed above, there are factors that are not dependent on the true nature of the disease—such as habits, cultural considerations, and insurance policies—that could affect diagnostic coding and the categorization used in this study. Indeed, our results suggest that there is a difference in coding between the 2 countries and that the coding may have changed, particularly for meniscus tears in Finland. However, the mean ages and the actual surgical procedure give us a reliable clue to the nature of the disease. In that vein, our results are more accurate than using the diagnosis code alone and suggest that the vast majority of patients undergoing meniscus surgery have degenerative—not traumatic—pathology of the knee.

In conclusion, the incidence of arthroscopy for knee OA declined similarly during the study period in Finland and Sweden. In Finland, but not in Sweden, the incidence of meniscus surgery increased during the same period. Furthermore, in Finland a substantial proportion of meniscal tears were coded as traumatic, a practice that is not supported by the mean age of the patients or the surgical procedures. We are currently witnessing a notable shift in the indications for knee arthroscopy. 7 high-quality randomized controlled trials assessing the benefit of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for patients with degenerative meniscal tears were recently published (Østerås et al. 2012, Herrlin et al. 2013, Katz et al. 2013, Sihvonen et al. 2013, Yim et al. 2013, Gauffin et al. 2014, Stensrud et al. 2015). Only 1 of these trials (Gauffin et al. 2014) provided any support for surgery of the degenerative knee. Implementation of evidence takes several years before it is detected in nationwide registry studies. As we have data regarding the incidence of knee arthroscopy until 2012, we could not detect possible changes in the number of arthroscopies performed for degenerative knee disease—namely degenerative meniscus—after the latest evidence was published. The national variations in the surgical trends in degenerative knee disease between Finland and Sweden are remarkable. Further investigation is needed to determine the reasons for these trends, such as differences in reimbursement.

Acknowledgments

VM and JP were responsible for acquisition of data, and for analysis and interpretation of data. VM, RS, and LT were responsible for the study design. VM and RS wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared. The study did not receive any external funding.

References

- Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States 2005–2011. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41(10): 2333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P, Carr AJ, Campbell WB, Wennberg JE. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet 2013; 382(9898): 1121–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013; 21(9): 577–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camanho GL, Hernandez AJ, Bitar AC, Demange MK, Camanho LF. Results of meniscectomy for treatment of isolated meniscal injuries: correlation between results and etiology of injury. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2006; 61(2): 133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoforakis J, Pradhan R, Sanchez-Ballester J, Hunt N, Strachan RK. Is there an association between articular cartilage changes and degenerative meniscus tears? Arthroscopy 2005; 21(11): 1366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaghan PG, Dickson J, Grant R L; Guideline Development Group. Care and management of osteoarthritis in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2008; 336(7642): 502–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl WW, Krome J, Gordon ES, Rushing J, Smith BP, Poehling GG. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy 1997; 13(4): 456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosos GI, Pozo JL. The causes and mechanisms of meniscal injuries in the sporting and non-sporting environment in an unselected population. Knee 2004; 11(2): 143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, Hunter DJ, Aliabadi P, Clancy M, Felson DT.. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(11): 1108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson DT. Arthroscopy as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010; 24(1): 47–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauffin H, Tagesson S, Meunier A, Magnusson H, Kvist J. Knee arthroscopic surgery is beneficial to middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms: a prospective, randomised, single-blinded study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22(11): 1808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare KB, Vinther JH, Lohmander LS, Thorlund JB. Large regional differences in incidence of arthroscopic meniscal procedures in the public and private sector in Denmark. BMJ Open 2015; 5(2): e006659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker G, Guan J, Judge A, Dieppe P. Knee arthroscopy in England and Ontario: patterns of use, changes over time, and relationship to total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90(11): 2337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrlin SV, Wange PO, Lapidus G, Hållander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21(2): 358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen TT, Kannus P, Pihlajamäki H, Mattila VM. Pertrochanteric fracture of the femur in the Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register: validity of procedural coding, external cause for injury and diagnosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, Donnell-Fink LA, Guermazi A, Haas AK, Jones MH, Levy BA, Mandl LA, Martin SD, Marx RG, Miniaci A, Matava MJ, Palmisano J, Reinke EK, Richardson BE, Rome BN, Safran-Norton CE, Skoniecki DJ, Solomon DH, Smith MV, Spindler KP, Stuart MJ, Wright J, Wright RW, Losina E. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(18): 1675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan JP, Jamali A, Marder R. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, Giffin JR, Willits KR, Wong CJ, Feagan BG, Donner A, Griffin SH, D’Ascanio LM, Pope JE, Fowler PJ. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(11): 1097–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Widmer M, Maravic M, Gómez-Barrena E, de Pina Mde F, Manno V, Torre M, Walter WL, de Steiger R, Geesink RG, Peltola M, Röder C. International survey of primary and revision total knee replacement. Int Orthop 2011; 35(12): 1783–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazic S, Boughton O, Hing C, Bernard J. Arthroscopic washout of the knee: a procedure in decline. Knee 2014; 21(2): 631–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen J, Lehtovirta J, et al. . THL-Toimenpideluokitus (in Finnish) THL, 2013.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, Olausson PO. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila VM, Sillanpää P, Iivonen T, Parkkari J, Kannus P, Pihlajamäki H. Coverage and accuracy of diagnosis of cruciate ligament injury in the Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register. Injury 2008; 39(12): 1373–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf MH, Barrett GR. Prospective evaluation of 1485 meniscal tear patterns in patients with stable knees. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32(3): 675–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM. Effect of physician ownership of specialty hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers on frequency of use of outpatient orthopedic surgery. Arch Surg 2010; 145(8): 732–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, Hollingsworth JC, Ashton CM, Wray NP. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002; 347(2): 81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The chronic osteoarthritis management initiative of the U.S. bone and joint initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 43(6): 701–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Official Statistics of Finland (OSF) Population structure [e-publication] 2015. from: http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/index_en.html

- Østerås H, Østerås B, Torstensen TA. Medical exercise therapy, and not arthroscopic surgery, resulted in decreased depression and anxiety in patients with degenerative meniscus injury. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2012; 16(4): 456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehling GG, Ruch DS, Chabon SJ. The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clin Sports Med 1990; 9(3): 539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts A, Harrast JJ, Harner CD, Miniaci A, Jones MH. Practice patterns for arthroscopy of osteoarthritis of the knee in the United States. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40(6): 1247–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J, Hunter D, Irrgang J, Jones MH, Levy B, Marx R, Snyder-Mackler L, Watters W C 3rd, Haralson RH 3rd, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Boyer KM, Anderson S, St Andre J, Sluka P, McGowan R. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee (nonarthroplasty). J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009; 17(9): 591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgaglione NA. Meniscus repair update: current concepts and new techniques. Orthopedics 2005; 28(3): 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Järvinen T L; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(26): 2515–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen Klassifikation av kirurgiska åtgärder 1997 2004. from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10244/2004-4-1_200441.pdf

- Socialstyrelsen. Öppna jämförelser av hälsooch sjukvårdens kvalitet och effektivitet: Jämförelser mellan landsting 2009. from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2009/2009-11-2

- Socialstyrelsen. Öppna jämförelser av hälso- och sjukvård 2014. from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/oppnajamforelser/halso-och-sjukvard

- Statistics Sweden Summary of Population Statistics 1960 - 2013. 2015. from: http://www.scb.se/

- Stensrud S, Risberg MA, Roos EM. Effect of exercise therapy compared with arthroscopic surgery on knee muscle strength and functional performance in middle-aged patients with degenerative meniscus tears: a 3-mo follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 94(6): 460–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40(6): 505–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlund JB, Hare KB, Lohmander LS. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from 2000 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(3): 287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim JH, Seon JK, Song EK, Choi JI, Kim MC, Lee KB, Seo HY. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41(7): 1565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt KD, Croft P, Doherty M, Dougados M, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kwoh K, Lohmander LS, Tugwell P. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010; 18(4): 476–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]