Abstract

Background and purpose

Currently, Propionibacterium is frequently recognized as a causative microorganism of prosthetic joint infection (PJI). We assessed treatment success at 1- and 2-year follow-up after treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI of the shoulder, hip, and knee. Furthermore, we attempted to determine whether postoperative treatment with rifampicin is favorable.

Patients and methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in which we included patients with a primary or revision joint arthroplasty of the shoulder, hip, or knee who were diagnosed with a Propionibacterium-associated PJI between November 2008 and February 2013 and who had been followed up for at least 1 year.

Results

We identified 60 patients with a Propionibacterium-associated PJI with a median duration of 21 (0.1–49) months until the occurrence of treatment failure. 39 patients received rifampicin combination therapy, with a success rate of 93% (95% CI: 83–97) after 1 year and 86% (CI: 71–93) after 2 years. The success rate was similar in patients who were treated with rifampicin and those who were not.

Interpretation

Propionibacterium-associated PJI treated with surgery in combination with long-term antibiotic administration had a successful outcome at 1- and 2-year follow-up irrespective of whether the patient was treated with rifampicin. Prospective studies are needed to determine whether the use of rifampicin is beneficial in the treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI.

A prosthetic joint infection (PJI) occurs in 1.5–3% of cases after primary joint arthroplasty (Ong et al. 2009, Kurtz et al. 2010, Singh et al. 2012), whereas the risk of PJI after revision arthroplasty is even higher (Phillips et al. 2003). Propionibacterium is involved in about 10% of cases, and is a more common causative organism of PJI in shoulder arthroplasty than in other joint arthroplasties (Levy et al. 2008, Corvec et al. 2012). In recent years, the number of Propionibacterium-associated PJIs has been increasing (Bjerke-Kroll et al. 2014), probably due to improved diagnostic modalities such as prolonged cultivation time of tissue cultures and the use of implant sonication (Achermann et al. 2014).

Propionibacterium is a gram-positive, relatively slow-growing microaerophilic rod that is known to be a major colonizer and inhabitant of the human skin, especially the sebaceous glands. It is recognized to be an important opportunistic pathogen causing implant-associated infection, including PJI, due to its ability to form biofilms (Ramage et al. 2003, Bayston et al. 2007a). Propionibacterium causes a delayed, low-grade infection that usually occurs 3–24 months or more after joint replacement surgery (Levy et al. 2008, Piper et al. 2009, Singh et al. 2012). Distinguishing PJI with Propionibacterium from aseptic failure can be difficult due to subtle clinical signs and symptoms, such as implant loosening or persistent pain (Zimmerli et al. 2004, Zappe et al. 2008).

In general, treatment of a PJI involves surgery involving debridement with retention of the prosthesis, 1- or 2-stage exchange arthroplasty, resection arthroplasty, arthrodesis, or amputation followed by prolonged antibiotic treatment (Zimmerli et al. 2004). For the treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI, the present clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend monotherapy with either penicillin G, ceftriaxone, clindamycin, or vancomycin (Osmon et al. 2013). Taking into account the established effectiveness of rifampicin in staphylococcal PJI (Zimmerli et al. 1998, Baldoni et al. 2009, John et al. 2009, El Helou et al. 2010) and the few clinical studies demonstrating positive outcomes of Propionibacterium-associated PJI treated with an antimicrobial regimen including rifampicin (Zeller et al. 2007, Levy et al. 2008), combination therapy with rifampicin may be favorable in treating Propionibacterium-associated PJI.

We assessed treatment success at 1- and 2-year follow-up after treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI of the shoulder, hip, and knee. We also attempted to determine whether postoperative antibiotic treatment with rifampicin is favorable in the treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI.

Patients and methods

Patients

All intraoperative tissue cultures that were positive for Propionibacterium, taken between November 2008 and April 2013 at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery in Sint Maartenskliniek, the Netherlands, were reviewed to retrospectively identify patients with a Propionibacterium-associated PJI after primary or revision joint arthroplasty of the shoulder, hip, or knee who had been treated with surgery and antibiotics. Patients were included if at least 2 intraoperative tissue cultures had been positive for the same Propionibacterium strain, antimicrobial treatment had been given, and there had been a minimal follow-up time of 1 year after final treatment. Demographic, clinical, laboratory, microbiological, and therapeutic data were collected from the patients’ medical records. Patients were excluded if the inclusion criteria were not met or if their medical records were not available.

Microbiological methods

Periprosthetic tissue samples (5–10 per patient) were cultured both aerobically and anaerobically for 10 days at 35°C on chocolate and MacConkey agar plates with 5% sheep blood, and in thioglycollate medium. On direct plates, Propionibacterium acnes grew within 3-4 days. Thioglycollate was incubated for at least 4 days before subcultures where done on the same primary plates. In general, a final positive result for Propionibacterium acnes was reported within a week. All microorganisms were routinely identified with MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltronics, Bremen, Germany).

Propionibacterium acnes was also tested for catalase, indole, and nitrate reductase. Antibacterial susceptibility testing of penicillin, clindamycin, and rifampicin was done with E test strips (bioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) using a MacFarland 1 inoculum, incubated anaerobically for 48–72 h and interpreted according to EUCAST for penicillin and clindamycin (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/). There are no breakpoints set for rifampicin.

Treatment

In all patients, treatment consisted of surgery and a 3-month postoperative antimicrobial regimen. The choice of surgical procedure was determined by the preoperative diagnosis, based on anamnesis, physical examination, radiological data, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), white blood cell (WBC) count, and in some cases a sterile arthrocentesis. 4 types of PJI were defined according to the classification by Tsukayama et al. (1996): an early postoperative infection (< 1 month after index surgery), a late chronic infection (≥ 1 month after index surgery), an acute hematogenous infection (antecedent bacteremia with acute onset of symptoms in affected joint with the prosthesis), and infection diagnosed from positive intraoperative cultures (≥ 2 positive cultures of the same specimen obtained at the time of revision operation).

An open debridement and prosthesis retention was performed if an early postoperative or acute hematogenous PJI was diagnosed. Those patients with a late chronic infection were managed with a 2-stage exchange arthroplasty. Patients who, preoperatively, were not suspected of having an infection, e.g. with aseptic loosening, polyethylene wear, instability, or prosthesis dysfunction, were treated with a 1-stage exchange arthroplasty. In these patients, a PJI was therefore diagnosed from positive intraoperative cultures. Antibiotic treatment with cefazoline (1,000 mg three times a day intravenously (i.v.)) was started intraoperatively after taking tissue cultures, and was continued for 5 days or until the results of the tissue cultures were available. A switch in antimicrobial treatment took place, guided by the positive cultures, and was continued in all patients orally (p.o.) or i.v. for a period of 3 months postoperatively. We identified 2 antimicrobial treatment groups, those with and without additional rifampicin. Whether a patient received additional rifampicin depended on the personal preference of the treating physician. Side effects of the antimicrobial treatment were extracted from the medical records.

Success of treatment

Failure of the retained and replaced prosthesis after finishing antimicrobial treatment was defined as a relapse, reinfection, and/or removal of the prosthesis for any reason. A relapse was defined as positive cultures yielding the same microorganism as the initial intraoperative samples. A reinfection was defined as a new infection with another pathogen.

Statistics

Differences in patient characteristics in the 2 treatment groups were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate for categorical data, and the independent t-test was used for continuous data. We checked for assumptions of continuous data and the homogeneity of variance was fulfilled (Levene’s test, p > 0.05). To determine the cumulative probability of treatment failure, we performed a Kaplan-Meier analysis with 95% confidence intervals. A relapse, reinfection, or removal of the prosthesis for any reason was defined as the endpoint. Patients who had their implant and no signs of infection at the end of the study period—or who had died during the study period—were censored. To compare treatment outcome in patients treated with and without rifampicin, log-rank analysis was used. All statistical analyses were done using IBM SPSS statistics version 20.0. Any p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

Approval of the local ethics committee was obtained on January 22, 2014 (registration number 608).

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 60 patients. The characteristics of the 2 antimicrobial treatment groups, those with and without rifampicin combination therapy, did not differ statistically significantly from each other (Table 1). The clinical presentation prior to the diagnosis of Propionibacterium-associated PJI consisted mainly of persistent joint pain (in 49 of the 60 patients) and joint stiffness (in 25 of the 60). About a quarter of patients had an elevated ESR and CRP. The median number of intraoperative tissue cultures obtained was 6 (5–10) per patient with a median of 3 (2–9) positive cultures. In 57 of the 60 patients, tissue cultures gave Propionibacterium acnes. The other 3 cases were caused by an unspecified Propionibacterium species. A monomicrobial infection was found in 47 patients. In 11 of 13 patients, tissue cultures showed a polymicrobial infection with Propionibacterium species and coagulase-negative staphylococci.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of 60 patients with Propionibacterium-associated PJI, presented according to their postoperative antimicrobial treatment

| Characteristic | Rifampicin (n = 39) |

No rifampicin (n = 21) |

Total group (n = 60) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of joint, n | 1.0 | |||

| Knee | 15 | 9 | 24 | |

| Hip | 12 | 6 | 18 | |

| Shoulder | 12 | 6 | 18 | |

| Type of arthroplasty, n | ||||

| Primary/revision | 31/8 | 15/6 | 46/14 | |

| Age at PJI diagnosisa | 69 (40–78) | 69 (47–80) | 69 (40–80) | 0.5 |

| Sex, female/male | 22/17 | 7/14 | 29/31 | 0.09 |

| BMI, kg/m2a | 28 (21–50) | 28 (22–35) | 28 (21–50) | 0.2 |

| Medical history of PJI, n | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.6 |

| Missing data | 6 | 0 | 6 | |

| Clinical presentation, n | ||||

| Missing data | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Joint pain | 31 | 18 | 49 | 1.0 |

| Stiffness | 15 | 10 | 25 | 0.5 |

| Tumor | 9 | 7 | 16 | 0.4 |

| Instability | 7 | 8 | 15 | 0.1 |

| Rubor | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.4 |

| Sinus tract | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.6 |

| Calor | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Fever | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Wound leakage | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Laboratory diagnostics | ||||

| ESR > 30 mm/h | 12 | 6 | 18 | 0.5 |

| Missing ESR data | 5 | 3 | 8 | |

| CRP > 10 mg/L | 10 | 6 | 16 | 0.6 |

| Missing CRP data | 8 | 7 | 15 | |

| Leucocytes, × 109/La | 7.9 (5.2–15) | 7.5 (4.9–13) | 7.7 (4.9–15) | 0.6 |

| Missing data, n | 13 | 10 | 23 | |

| Microbiological diagnostics | ||||

| No. of tissue culturesa | 7 (6–9) | 6 (5–10) | 6 (5–10) | 0.3 |

| No. of positive culturesa | 3 (2–9) | 3 (2–7) | 3 (2–9) | 0.8 |

| Mono/polymicrobial | 28/11 | 19/2 | 47/13 | 0.1 |

| PJI classificationb | 0.7 | |||

| Early postoperative | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Late chronic | 9 | 4 | 13 | |

| Acute hematogenous | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Positive intraoperative cultures | 25 | 16 | 41 |

PJI: periprosthetic joint infection; BMI: body mass index; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Values are median (range)

According to Tsukayama et al. (1996): early postoperative infection (< 1 month after index surgery), late chronic infection (> 1 month after index surgery), acute hematogenous infection (antecedent bacteremia with acute onset of symptoms in affected joint with the prosthesis), or infection diagnosed from positive intraoperative cultures (≥ 2 positive cultures of the same specimen obtained at the time of revision operation).

Preoperatively, a small proportion of patients were suspected of having an infection (19/60). 4 patients were diagnosed with an early postoperative infection after primary joint arthroplasty. They presented with symptoms of an acute infection consisting of redness, purulent drainage, or persistent wound leakage. The intraoperative cultures showed a polymicrobial infection in 3 patients (2 hips and 1 knee), and a monomicrobial infection in 1 patient with Propionibacterium acnes after primary shoulder arthroplasty. All 4 patients were treated with debridement and prosthesis retention, and with antibiotics for 3 months. 3 of them received additional rifampicin. A reinfection occurred in 1 patient who was not treated with rifampicin combination therapy.

Preoperatively, the remaining patients (a majority) were not suspected of having infection and were diagnosed with a Propionibacterium-associated PJI from positive intraoperative tissue cultures (41/60). Preoperatively, these patients mainly complained of having pain, joint stiffness, and instability. In all 41 patients, the intraoperative cultures showed a monomicrobial infection with Propionibacterium acnes. They were managed with a one-stage revision arthroplasty followed by an antibiotic regimen for 3 months. 25 of the 41 patients received rifampicin combination therapy. At last follow-up, 4 failures had occurred—2 relapse and 2 reinfections (3 in the group treated with rifampicin and 1 in the group treated without rifampicin).

Treatment

All patients were treated with a combination of surgery and a 3-month postoperative antimicrobial regimen (Table 2).

Table 2.

Surgical treatment and postoperative antimicrobial regimen in 60 patients with Propionibacterium-associated PJI, presented according to their postoperative antimicrobial treatment

| Characteristic | Rifampicin (n = 39) |

No rifampicin (n = 21) |

Total group (n = 60) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical treatment | 0.5 | |||

| Debridement and prosthesis retention | 5 | 1 | 6 | |

| 1-stage revision (partial revision) | 25 (5) | 16 (5) | 41 (10) | |

| 2-stage revision | 9 | 4 | 13 | |

| Antibiotic treatment (daily doses) | ||||

| Clindamycin 600 mg x 3 and rifampicin 450 mg x 2 | 33 | – | 33 | |

| Teicoplanin 400 mg x 1 i.v. and rifampicin 450 mg x 2 | 6 | – | 6 | |

| Clindamycin 600 mg x 3 | – | 16 | 16 | |

| Amoxicillin 500 mg x 4 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Ciprofloxacin 750 mg x 2 and clindamycin 600 mg x 3 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Doxycycline 200 mg x 1 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Linezolid 600 mg x 2 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Teicoplanin 400 mg x 1 i.v. | – | 1 | 1 |

i.v.: intravenously.

Surgical treatment

6 patients underwent debridement with prosthesis retention because of an early postoperative infection (4/6) or a hematogenous infection (2/6). 13 patients, suspected preoperatively of having a late chronic infection, underwent a two-stage exchange arthroplasty. 41 patients who were not suspected preoperatively of having an infection were diagnosed from positive intraoperative cultures and treated with a one-stage exchange arthroplasty, 10 of which had partial revision of the prosthesis, i.e. the femoral/humeral or acetabular/glenoid component.

Antimicrobial regimen

After antimicrobial treatment with cefazoline intravenously (1,000 mg 3 times a day), a switch in antimicrobial treatment took place, guided by the positive intraoperative cultures. In all the patients included, low MICs were observed for clindamycin, penicillin, and rifampicin in the Propionibacterium isolates tested (MIC < 0.5 mg/L). 39 patients received a combination of antibiotics including rifampicin. 33 of these 39 patients received a combination of clindamycin (600 mg 3 times a day) and rifampicin (450 mg twice a day). 21 patients received antimicrobial treatment without rifampicin. 16 of 21 patients received clindamycin only (600 mg 3 times a day). In 25 patients, side effects of the antimicrobial regimen were reported, 16 of them in the group treated with rifampicin. Most side effects (22/25) were gastrointestinal symptoms, and 1 patient with diarrhea was diagnosed with Clostridium difficile infection and treated with a course of metronidazole (500 mg 3 times a day). All patients could continue their antibiotic treatment; in 7 cases, the dose of the antibiotic administered had to be diminished. Few patients (3/25) developed an allergic skin reaction. In these cases, there was a switch of antibiotic regimen.

Outcome of treatment

60 patients were followed for at least 1 year, with a median duration of 21 (0.1–49) months until the occurrence of treatment failure. During the follow-up of 2 years, 7 failures occurred, 4 patients had a relapse infection with a Propionibacterium species, and 3 patients had a reinfection with another pathogen. These 7 patients underwent revision surgery in which the prosthesis was removed (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Number and types of failures in 60 patients with Propionibacterium-associated PJI, presented according to their postoperative antimicrobial treatment

| Characteristic | Rifampicin (n = 39) |

No rifampicin (n = 21) |

Total group (n = 60) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failures | ||||

| 1-year follow-up | 2/39 | 2/21 | 4/60 | 0.7 |

| 2-year follow-up | 4/23 | 3/13 | 7/36 | 0.6 |

| Survival, median (range), months | 19 (0.1–49) | 23 (0.2–47) | 21 (0.1–49) | 0.9 |

| Type of failure | ||||

| Relapsea | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.4 |

| Reinfectionb | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.5 |

Relapse: defined as positive cultures growing the same microorganism as the initial intraoperative samples.

Reinfection: defined as a new infection with a pathogen other than that in the initial intraoperative samples.

Table 4.

Overview of the patient characteristics of 7 failed cases treated for Propionibacterium-associated PJI

| Case | Age | Sex | Location of joint | Preoperative diagnosis | Micro-organism(s) | PJI classificationa | Antibiotic treatment | Change in antibiotic treatment | Surgery | Duration of survival (months) | Type of failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | M | Shoulder | Suspected infection | P. acnes | Late chronic | Clindamycin | No | 2-stage revision | 0.2 | Relapse |

| 2 | 72 | F | Shoulder | Dysfunction | P. acnes | PIOC | Clindamycin + rifampicin | No | 1-stage revision (total revision) |

19 | Reinfection |

| 3 | 56 | M | Knee | Dysfunction | P. acnes | PIOC | Clindamycin + rifampicin | No | 1-stage revision (total revision) |

0.1 | Reinfection |

| 4 | 40 | F | Hip | Aseptic loosening | P. acnes | PIOC | Clindamycin + rifampicin | No | 1-stage revision (partial revision) |

7 | Relapse |

| 5 | 78 | M | Shoulder | Suspected infection | P. acnes | Late chronic | Clindamycin + rifampicin | No | 2-stage revision | 14 | Relapse |

| 6 | 50 | M | Hip | Suspected infection | P. acnes + Morganelli morganii | Early postop. | Clindamycin + ciprofloxacin | Yesb | Debridement and prosthesis retention | 0.1 | Reinfection |

| 7 | 56 | M | Shoulder | Dysfunction | P. acnes | PIOC | Clindamycin | No | 1-stage revision (total revision) |

23 | Relapse |

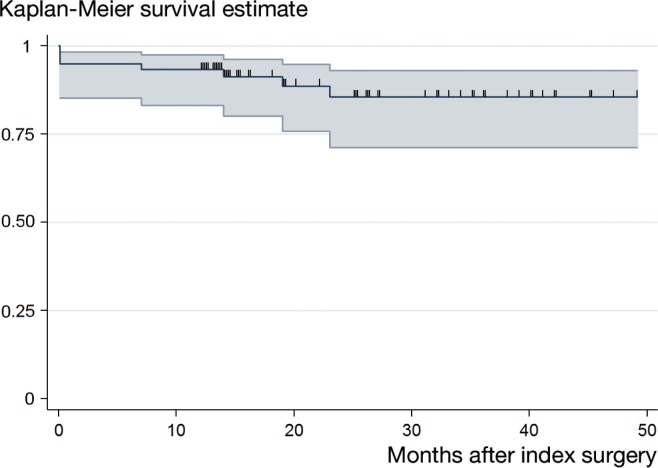

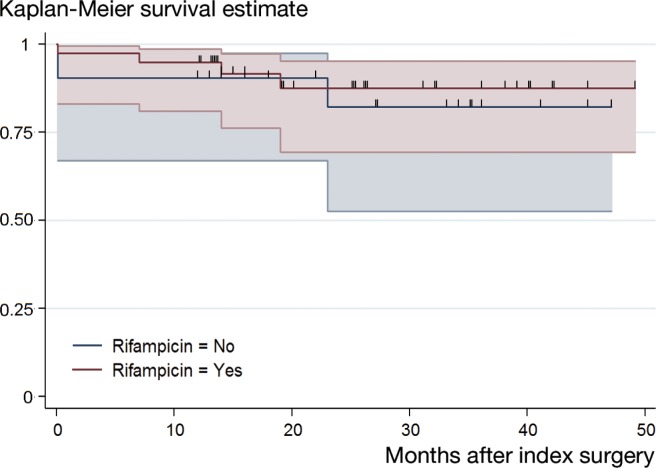

Using the Kaplan-Meier method, an overall cumulative success rate of 93% (95% CI: 83–97) after 1 year and 86% (CI: 71–93) after 2 years was found (Figure 1). Patients treated without rifampicin combination therapy had a cumulative success rate of 90% (CI: 67–98) after 1 year and 82% (CI: 53–94) after 2 years. A cumulative success rate of 95% (CI: 81–99) and 88% (CI: 69–95) was reached in patients treated with rifampicin combination therapy after 1 year and 2 years, respectively (Figure 2). Comparison of the overall cumulative success rate of patients treated with and without rifampicin revealed a p-value of 0.7 (log-rank test).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of 60 patients treated for Propionibacterium-associated PJI. The cumulative success rate was 93% (95% CI: 83–97) and 86% (95% CI: 71–93) after 1 year and 2 years, respectively. The small vertical spikes represent the censored data.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients treated for Propionibacterium-associated PJI with and without rifampicin combination therapy. A cumulative success rate of 90% (95% CI: 67–98) and 82% (95% CI: 53–94) was found in patients treated without rifampicin after 1 year and 2 years, respectively. A cumulative success rate of 95% (95% CI: 81–99) after 1 year and 88% (95% CI: 69–95) after 2 year was reached in patients treated with rifampicin. Overall comparison of the cumulative success rates revealed a p-value of 0.7 (log-rank test). The small vertical spikes represent the censored data.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study was conducted to determine the success rates after treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI of the shoulder, hip, and knee at 1- and 2-year follow-up. We also attempted to determine if there was a difference in treatment success in patients treated with or without rifampicin combination therapy. We found an overall cumulative success rate of 93% after 1-year follow-up and 86% after and 2-year follow-up. Similar treatment success was found in patients who were treated with or without rifampicin combination therapy.

The patient characteristics of our cohort are comparable to those in previous studies, and support the evidence that clinical findings before the diagnosis of Propionibacterium-associated PJI are subtle (Zappe et al. 2008, Dodson et al. 2010). Furthermore, the success rates we observed are in line with the few published data. Zeller et al. (2007) found a success rate after 2-year follow-up of 92% in 48 patients who were treated for Propionibacterium-associated PJI. All of these 48 patients underwent surgery and underwent long-term antibiotic treatment. Most of these patients received an antibiotic regimen of cefalosporines and rifampicin or clindamycin and rifampicin. A smaller study by Levy et al. (2008) found favorable results from combination therapy with amoxicillin and rifampicin.

Unexpectedly, we did not find a higher success rate in patients treated with rifampicin combination therapy, despite the established effectiveness of rifampicin in staphylococcal PJI (Zimmerli et al. 1998, Baldoni et al. 2009, John et al. 2009, El Helou et al. 2010) and the successful eradication of Propionibacterium biofilms with rifampicin in in-vitro studies (Bayston et al. 2007b, Furustrand Tafin et al. 2012) and in-vivo studies (Furustrand Tafin et al. 2012). Our study results can be explained in several ways. First of all, most of our patients underwent surgical treatment consisting of exchange arthroplasty in combination with long-term postoperative antimicrobial treatment with or without rifampicin. Studies researching the effect of additional rifampicin in the treatment of staphylococcal PJI were performed in patients undergoing debridement and retention of the prosthesis (Zimmerli et al. 1998, El Helou et al. 2010). Since rifampicin is known to be a biofilm-active antibiotic, the additional benefit when the infected prosthesis has already been removed is debatable. Secondly, most of our patients who received rifampicin were treated with a combination of clindamycin and rifampicin. Several authors have described a decrease in clindamycin plasma concentration, which is influenced by co-administration of rifampicin (Zeller et al. 2010, Bouazza et al. 2012, Join-Lambert et al. 2014, Curis et al. 2015), presumably because rifampicin is a potent inducer of hepatic cytochrome P-450 3A4 (Niemi et al. 2003), the main metabolic pathway of clindamycin (Wynalda et al. 2003). This could result in a less than optimal treatment. Still, it is uncertain whether this conflicting interaction between clindamycin and rifampicin is of clinical relevance, because several in-vitro, in-vivo, and clinical data show good effectiveness of clindamycin and rifampicin combination therapy against Staphylococcus-related osteoarticular infections (Arditi and Yogev 1989, O’Reilly et al. 1992, Zeller et al. 2010, Czekaj et al. 2011, Curis et al. 2015).

Our study had some limitations. First, the historical study design and the use of data not primarily intended for research resulted in bias from missing data. Patients were only included in the analyses if there was a minimum follow-up of 1 year, and notes were present in the patients’ medical records which may have contributed to selection bias and given an overestimation or underestimation of the success rates calculated. Another shortcoming, and contributory factor to selection bias, was the choice of antibiotic treatment with or without rifampicin, which was based on personal preference. No predefined criteria were used to substantiate the choice of whether or not a patient should receive rifampicin combination therapy. Furthermore, we included a small and heterogeneous group of patients with different types of PJIs of the knee, hip, and shoulder, which were treated with different types of surgery and antimicrobial treatment regimens. This would have contributed to a lack of power and increased the probability of type-2 error. A possible difference in success rates between the 2 treatment groups could be missed. It could also be that the null hypothesis was correct and that there was no difference in success rates between the 2 treatment groups.

In summary, to our knowledge this is the first clinical study to compare antibiotic treatment regimens in Propionibacterium-associated PJI. A combination of surgery and long-term antibiotic treatment postoperatively resulted in an overall success rate of 93% at 1-year follow-up and 86% at 2-year follow-up. No significant difference in treatment success was found between patients treated with rifampicin combination therapy and those treated without. Prospective studies are required to determine the benefit of adding rifampicin for the treatment of Propionibacterium-associated PJI.

AMEJ: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, administrative support, and drafting of the manuscript. MLH: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and revision of the manuscript. JFM and FV: acquisition of data and revision of the manuscript. JHMG: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared. The study was not supported by any company or any grants.

References

- Achermann Y, Goldstein E J, Coenye T, Shirtliff M E.. Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27 (3): 419-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditi M, Yogev R.. In vitro interaction between rifampin and clindamycin against pathogenic coagulase-negative staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989; 33 (2): 245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A.. Linezolid alone or combined with rifampin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in experimental foreign-body infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53 (3): 1142-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayston R, Ashraf W, Barker-Davies R, Tucker E, Clement R, Clayton J, Freeman B J, Nuradeen B.. Biofilm formation by Propionibacterium acnes on biomaterials in vitro and in vivo: impact on diagnosis and treatment. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007a; 81 (3): 705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayston R, Nuradeen B, Ashraf W, Freeman B J.. Antibiotics for the eradication of Propionibacterium acnes biofilms in surgical infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007b; 60 (6): 1298-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerke-Kroll B T, Christ A B, McLawhorn A S, Sculco P K, Jules-Elysee K M, Sculco T P.. Periprosthetic joint infections treated with two-stage revision over 14 years: an evolving microbiology profile. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (5): 877-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouazza N, Pestre V, Jullien V, Curis E, Urien S, Salmon D, Treluyer J M.. Population pharmacokinetics of clindamycin orally and intravenously administered in patients with osteomyelitis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 74 (6): 971-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvec S, Portillo M E, Pasticci B M, Borens O, Trampuz A.. Epidemiology and new developments in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Int J Artif Organs 2012; 35 (10): 923-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curis E, Pestre V, Jullien V, Eyrolle L, Archambeau D, Morand P, Gatin L, Karoubi M, Pinar N, Dumaine V, Van J C, Babinet A, Anract P, Salmon D.. Pharmacokinetic variability of clindamycin and influence of rifampicin on clindamycin concentration in patients with bone and joint infections. Infection 2015; 43 (4): 473-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekaj J, Dinh A, Moldovan A, Vaudaux P, Gras G, Hoffmeyer P, Lew D, Bernard L, Uckay I.. Efficacy of a combined oral clindamycin-rifampicin regimen for therapy of staphylococcal osteoarticular infections. Scand J Infect Dis 2011; 43 (11-12): 962-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson C C, Craig E V, Cordasco F A, Dines D M, Dines J S, Dicarlo E, Brause B D, Warren RF .. Propionibacterium acnes infection after shoulder arthroplasty: a diagnostic challenge. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 19 (2): 303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Helou O C, Berbari E F, Lahr B D, Eckel-Passow J E, Razonable R R, Sia I G, Virk A, Walker R C, Steckelberg J M, Wilson W R, Hanssen A D, Osmon D R.. Efficacy and safety of rifampin containing regimen for staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and retention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 29 (8): 961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furustrand Tafin U, Corvec S, Betrisey B, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A.. Role of rifampin against Propionibacterium acnes biofilm in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56 (4): 1885-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John A K, Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rentsch K, Schaerli P, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A.. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53 (7): 2719-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Join-Lambert O, Ribadeau-Dumas F, Jullien V, Kitzis M D, Jais J P, Coignard-Biehler H, Guet-Revillet H, Consigny P H, Delage M, Nassif X, Lortholary O, Nassif A.. Dramatic reduction of clindamycin plasma concentration in hidradenitis suppurativa patients treated with the rifampin-clindamycin combination. Eur J Dermatol 2014; 24 (1): 94-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S M, Ong K L, Lau E, Bozic K J, Berry D, Parvizi J.. Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (1): 52-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy P Y, Fenollar F, Stein A, Borrione F, Cohen E, Lebail B, Raoult D.. Propionibacterium acnes postoperative shoulder arthritis: an emerging clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46 (12): 1884-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemi M, Backman J T, Fromm M F, Neuvonen P J, Kivisto K T.. Pharmacokinetic interactions with rifampicin: clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42 (9): 819-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly T, Kunz S, Sande E, Zak O, Sande M A, Tauber M G.. Relationship between antibiotic concentration in bone and efficacy of treatment of staphylococcal osteomyelitis in rats: azithromycin compared with clindamycin and rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992; 36 (12): 2693-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong K L, Kurtz S M, Lau E, Bozic K J, Berry D J, Parvizi J.. Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24 (6 Suppl): 105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmon D R, Berbari E F, Berendt A R, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg J M, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson W R, Infectious Diseases Society of A . Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56 (1): e1-e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips C B, Barrett J A, Losina E, Mahomed N N, Lingard E A, Guadagnoli E, Baron J A, Harris W H, Poss R, Katz J N.. Incidence rates of dislocation, pulmonary embolism, and deep infection during the first six months after elective total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A (1): 20-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper K E, Jacobson M J, Cofield R H, Sperling J W, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Osmon D R, McDowell A, Patrick S, Steckelberg J M, Mandrekar J N, Fernandez Sampedro M, Patel R.. Microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic shoulder infection by use of implant sonication. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47 (6): 1878-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage G, Tunney M M, Patrick S, Gorman S P, Nixon J R.. Formation of Propionibacterium acnes biofilms on orthopaedic biomaterials and their susceptibility to antimicrobials. Biomaterials 2003; 24 (19): 3221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J A, Sperling J W, Schleck C, Harmsen W S, Cofield R H.. Periprosthetic infections after total shoulder arthroplasty: a 33-year perspective. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21 (11): 1534-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukayama D T, Estrada R, Gustilo R B.. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. A study of the treatment of one hundred and six infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78 (4): 512-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynalda M A, Hutzler J M, Koets M D, Podoll T, Wienkers L C.. In vitro metabolism of clindamycin in human liver and intestinal microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos 2003; 31 (7): 878-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappe B, Graf S, Ochsner P E, Zimmerli W, Sendi P.. Propionibacterium spp. in prosthetic joint infections: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008; 128 (10): 1039-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller V, Ghorbani A, Strady C, Leonard P, Mamoudy P, Desplaces N.. Propionibacterium acnes: an agent of prosthetic joint infection and colonization. J Infect 2007; 55 (2): 119-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller V, Dzeing-Ella A, Kitzis M D, Ziza J M, Mamoudy P, Desplaces N.. Continuous clindamycin infusion, an innovative approach to treating bone and joint infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54 (1): 88-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Widmer A F, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner P E.. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA 1998; 279 (19): 1537-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE.. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (16): 1645-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]