Abstract

Objectives. To determine whether state medical marijuana laws “send the wrong message,” that is, have a local influence on the views of young people about the risks of using marijuana.

Methods. We performed multilevel, serial, cross-sectional analyses on 10 annual waves of the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2004–2013) nationally and for states with marijuana laws using individual- and state-level controls.

Results. Living in medical marijuana states was associated with more permissive views regarding marijuana across 5 different measures. However, these associations became non–statistically significant after we adjusted for state-level differences. By contrast, there was a consistent and significant national time trend toward more permissive attitudes, which was less pronounced among children of middle school age than it was among their older counterparts.

Conclusions. Passing medical marijuana laws does not seem to directly affect the views of young people in medical marijuana states. However, there is a national trend toward young people taking more permissive views about marijuana independent of any effects within states.

Since the earliest debates over medical marijuana in the 1960s, detractors have warned that relaxing marijuana control policies could “send the wrong message” to young people about the risks of using drugs.1 In the United States today, there is an accelerating trend toward the relaxation of state marijuana controls—which is demonstrated by new laws legalizing marijuana use for medicinal use in 24 states and the District of Columbia and for recreational use in 4 states and the District of Columbia. Attitudes and beliefs about addictive substances are forged during late adolescence and young adulthood.2,3 They are the strongest single predictor of drug consumption, even when compared with the combined effects of all other lifestyle determinants.4,5

A small but growing literature seeks to understand if and how changing state marijuana policies are affecting young people’s attitudes about drugs. So far, the evidence is mixed and inconclusive. Some surveys of high school seniors suggest that state decriminalization and legalization diminish perceptions of risk and disapproval, whereas others report no such effects.6–8 The first study of medical marijuana laws surveyed adolescents before and after passage of California’s 1996 statute, finding that youths reported fewer concerns about the risks of using cannabis after the law.9 A subsequent before–after comparison in Colorado strengthened the approach by adding a control group and found similar results.10

As more states have legalized medical marijuana, the literature has evolved into more comprehensive national studies. Wall et al.11 found that between 2002 and 2008, those aged 12 to 17 years living in states with medical marijuana laws perceived the drug as less risky than did those dwelling in other states. A key challenge in interpreting these results is disentangling cause from effect. These findings could indicate that medical marijuana laws promote more permissive attitudes among youths. They could also indicate that young people in medical marijuana states are influenced by the more liberal political zeitgeist that leads these states to legalize medical marijuana. A subsequent replication of Wall et al.’s study using fixed effects modeling to control for state-level confounding suggested that the latter interpretation cannot be ruled out.12

Although the literature is growing and providing a stronger basis for causal inference, there remain significant limitations. Studies have been confined to state-level data, thus failing to control for critical individual-level factors that shape attitudes about drugs, such as parental and peer group influences, school engagement, and religiosity.5,13–15 Researchers have also struggled to keep up with the fast pace of changing state drug policies. Few studies include critical years after 2010—a period of rapid acceleration in successful movements to legalize marijuana for medical and recreational use. And, uniformly, researchers have ignored age-related variation by pooling children from aged 12 to 17, or even to 24, years or studying a single age group in isolation.

We performed multilevel, serial, cross-sectional analyses on 10 annual waves of the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), including controls at both the individual and state levels as well as fixed effects to address time trends and state-level variation. We also stratified the analysis by theoretically relevant age groups. We hypothesized that middle school–aged children would be the least affected because they are less exposed to drug policy debates and developmentally are less prone to question adult prohibitions on drugs.16 High school–aged youths should be more influenced by changing state policies because, developmentally, they are more prone to social messaging on drugs.17,18 Finally, young adults are likely to be the most affected: being of voting age, they are more attuned to state policy debates and are in the peak years of engagement with marijuana across the lifespan.2,19

METHODS

Our primary data source was 10 annual waves of the NSDUH, from 2004 to 2013. Following a data use agreement with the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, our team obtained access to the de-identified individual-level data that included the state of residence for each respondent. Each wave of the NSDUH represents the US population in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. During the period we studied, no major changes in sampling, data collection, or instruments were made; thus comparability across survey years was preserved. Full details of the data collection protocols are available in US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration methodology reports.20 The total sample, pooled over 10 years, includes approximately 450 300 individuals. (Note that reported sample sizes must be rounded in accordance with US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration confidentiality requirements.) We stratified young people into 3 discrete age groups: middle school–aged youths (aged 12–14 years, rounded n = 111 100), high school–aged youths (aged 5–17 years, rounded n = 114 000), and young adults (aged 18–25 years, rounded n = 225 200).

Measures

All measures we used in the analysis were annually updated for each of the 10 survey years. Key outcome variables, drawn from the NSDUH and measured at the individual level, reflected attitudes about marijuana’s riskiness, accessibility, and social acceptability. All study participants were asked for their opinions on whether the use of marijuana weekly (i.e., 1–2 times a week) is “a great risk,” whether monthly marijuana use is “a great risk,” and whether marijuana is easy to obtain. Participants younger than 18 years were asked about their views on whether their parents would disapprove if they tried marijuana and whether their friends would disapprove. We dichotomized these 5 outcome variables, with a value of 1 indicating a more permissive view.

Additional individual-level variables were age-appropriate predictors that could confound the relationship between dwelling in states with medical marijuana laws and drug-related attitudes. For all age groups, these included gender, race/ethnicity, family income, and religiosity. For middle and high school–aged youths, we included additional age-appropriate controls on parental monitoring (i.e., whether parents enforce rules governing screen time or impose a curfew), living in a single-parent home, participation in group fights, and disliking school. For young adults, additional controls included employment, college attendance, parental status, and marital status. These factors, associated with “maturing out” of drug involvement, are strong predictors of less permissive attitudes on drugs in young adults.21

We augmented the NSDUH data with annually updated state-level data on medical marijuana laws as well as other relevant variables. For state-level controls, we drew on publicly available sources such as US Current Population Survey and Polidata,22 including unemployment rates, percentage employed in the manufacturing job sector, percentage immigrants, and Republican (vs Democrat) control of the state’s house and senate.

We started our systematic data collection on state medical marijuana laws by gathering all state statutes and subsequent regulations. We coded state laws on 17 dimensions measuring variation in their permissiveness, such as the amounts allowed for possession and cultivation, medical conditions covered, and number of dispensaries in each state.23 We validated our assessments with external sources, including those of legal researchers at ProCon, and we resolved any discrepancies through telephone interviews with state drug control officials. We conducted monthly updates to monitor changes in the regulations and amendments to state laws. We focused on a dichotomous measure: whether a state did or did not have a medical marijuana law during any particular year. This is because analyses of more nuanced measures, such as the duration and permissiveness of state laws, failed to produce statistically different results from the dichotomous measure.

Statistical Analysis

We concatenated 10 annual waves of the NSDUH and all state-level indicators into a single file. We conducted all analyses using Stata version 13.24 For each survey year, we used weights to adjust for sampling design effects and nonresponse.25 We used initial descriptive analyses to document secular trends at the national level. We performed causal modeling using logistic regression to predict the 5 binary outcomes separately for middle and high school–aged youths and young adults. Following Williams and others,26–29 we accounted for shared variance among participants within states by calculating SEs clustered at the state level annually.

In our initial set of logistic regression analyses, we incorporated all individual- and state-level controls as well as annual fixed effects (i.e., dummy variables to indicate each year of data). Our objective was to assess whether living in a state with a medical marijuana law predicted more permissive drug-related attitudes and whether those effects differed across age groups. In a second set of regressions, we introduced state-level fixed effects into the regressions (i.e., dummy variables indicating each state). The coefficients for each state controlled for any state-specific confounding not already captured by variables in the models. This allowed us to rule out the possibility that unobserved state-level confounders (e.g., more liberal social norms on drug use in medical marijuana states) could account for any associations found between state medical marijuana laws and young peoples’ attitudes.

RESULTS

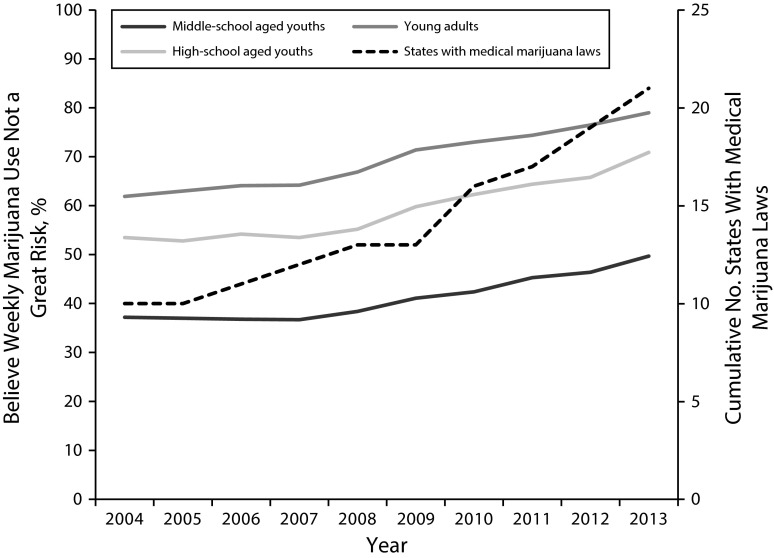

At the outset, in 2004, 10 states in the United States had enacted medical marijuana laws. By the study’s end, in 2013, 21 states plus the District of Columbia had done so (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). As Figure 1 illustrates, during this period, young people in all age groups grew less concerned about the riskiness of using marijuana on a weekly basis. The most pronounced change occurred among those of high school age: in 2004, 53% viewed the weekly use of marijuana as “not a great risk,” whereas by 2013, 71% did. We observed this trend for most other indicators of more permissive views on marijuana (Table B available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Figure 1 also demonstrates an age gradient in attitudes about marijuana, with those in older age groups holding more permissive views.

FIGURE 1—

Trends in Young People’s Attitudes About Marijuana and Medical Marijuana Laws: US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2004–2013

Note. Within each year, age group differences are statistically significant at P < .001; 2004–2013 differences are also significant at P < .01 for each age group.

There were pronounced demographic differences in the populations of young people living in states with medical marijuana laws compared with those who were not. These demographic differences—especially those associated with drug-related attitudes—underscored the importance of applying individual-level controls. In 2013, those living in medical marijuana states were disproportionately White and Hispanic (Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Young people in medical marijuana states were also less likely to report a high degree of religiosity along with an age-based gradient whereby religiosity dropped off in older age groups. Among young adults, those living in medical marijuana states were comparatively less likely to be married and to have children.

We used multivariate analyses to test the hypothesis that, controlling for confounders at the individual and state levels, young people dwelling in states with medical marijuana laws hold more permissive views about marijuana. Table 1 presents a full set of logistic regression models predicting the belief that using marijuana on a weekly basis is “not a great risk.” Across all age groups, there is a time trend toward more permissive views. In 2013 compared with 2004, young adults in medical marijuana states had double the odds of reporting that the weekly use of marijuana is not a great risk (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.95, 2.26; P < .001).

TABLE 1—

Adjusted Odds Ratios Predicting the Belief That Weekly Marijuana Use Is Not a Great Risk: US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2004–2013

| Variable | Middle School–Aged Youths, AOR (95% CI) | High School–Aged Youths, AOR (95% CI) | Young Adults, AOR (95% CI) |

| Lives in a medical marijuana state | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.29) | 1.31 (1.22, 1.40) |

| Survey year fixed effectsa | |||

| 2004 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2005 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) |

| 2006 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.12) |

| 2007 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 1.08 (1.02, 1.15) |

| 2008 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) | 1.15 (1.08, 1.22) |

| 2009 | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19) | 1.16 (1.05, 1.28) | 1.32 (1.20, 1.46) |

| 2010 | 1.20 (1.11, 1.30) | 1.30 (1.16, 1.44) | 1.50 (1.35, 1.67) |

| 2011 | 1.38 (1.27, 1.50) | 1.40 (1.28, 1.52) | 1.59 (1.44, 1.75) |

| 2012 | 1.17 (1.08, 1.27) | 1.37 (1.25, 1.50) | 1.78 (1.64, 1.92) |

| 2013 | 1.31 (1.21, 1.42) | 1.77 (1.61, 1.96) | 2.10 (1.95, 2.26) |

| Individual-level predictors | |||

| Female | 0.87 (0.85, 0.89) | 0.68 (0.67, 0.70) | 0.59 (0.58, 0.61) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| African American/Black | 1.68 (1.61, 1.75) | 1.34 (1.25, 1.44) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.41 (1.33, 1.51) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.21) | 0.56 (0.51, 0.60) |

| Other or multiple races | 1.20 (1.12, 1.29) | 0.94 (0.85, 1.04) | 0.69 (0.61, 0.78) |

| Income, $ | |||

| < 20 000 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 20 000–49 999 | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) |

| 50 000–74 999 | 0.73 (0.69, 0.78) | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) | 0.92 (0.88, 0.96) |

| 75 000–99 999 | 0.71 (0.66, 0.76) | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) | 0.90 (0.85, 0.94) |

| ≥ 100 000 | 0.63 (0.60, 0.66) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Religiosity | 0.65 (0.62, 0.68) | 0.52 (0.50, 0.54) | 0.50 (0.47, 0.52) |

| Has ≥ 1 children | NA | NA | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) |

| Ever been married | NA | NA | 0.63 (0.60, 0.66) |

| Parents monitor screen time or enforce curfew | 0.78 (0.75, 0.81) | 0.81 (0.79, 0.84) | NA |

| Single- or no-parent home vs 2 parents | 1.24 (1.20, 1.28) | 1.35 (1.31, 1.40) | NA |

| Was in a group fight | 1.61 (1.53, 1.70) | 1.72 (1.66, 1.78) | NA |

| Dislikes or hates school | 1.45 (1.40, 1.51) | 1.67 (1.63, 1.71) | |

| Not in school, did not work last week | NA | NA | 1.09 (1.06, 1.11) |

| State-level predictors | |||

| Republican-controlled state legislature | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.02) |

| Unemployment, % | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) |

| Manufacturing jobs, % | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) |

| Adult immigrant, % | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NA = not available. SEs are clustered at the state level.

Dummy variables to indicate each year of data.

Across all age groups, those more likely to report permissive views were males of lower incomes with less religiosity. For younger age groups, a reported lack of parental monitoring, disliking school, and participating in group fights predicted more permissive attitudes, and for young adults being unmarried did the same. Aspects of the state demographic and political environment played roles, albeit unevenly across models. The effects of living in a medical marijuana state appeared to be greater for young adults than for the 2 younger age groups (AOR = 1.31; CI = 1.22, 1.40 for young adults vs AOR = 1.21; CI = 1.15, 1.27 and 1.13, 1.29 for middle school and high school–aged youths, respectively).

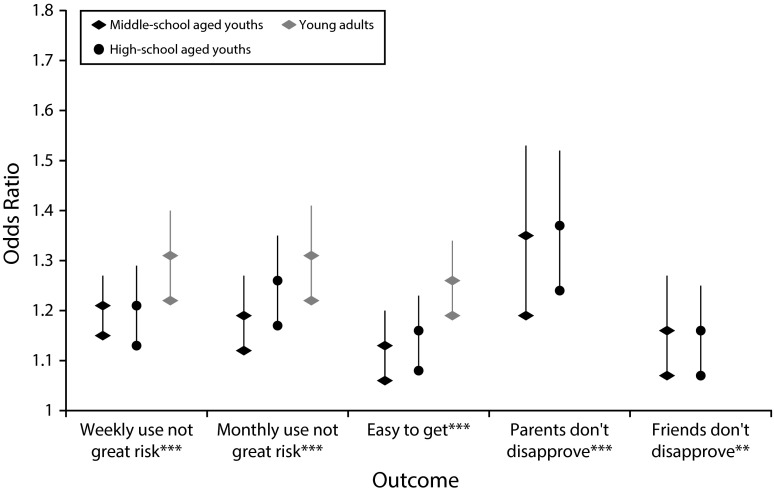

We used the same independent variables to evaluate 4 other drug-related attitudes. Figure 2 provides AORs and 95% CIs for all the outcomes studied. Across all 3 age groups, living in a medical marijuana state significantly increased the odds of reporting more permissive views, including the beliefs that weekly and monthly use are not great risks, that marijuana is easy to obtain, and that parents and peers would not disapprove if one tried marijuana. (Complete results are available in Tables D–P as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.) In most cases, the ORs followed a positive stepped age gradient.

FIGURE 2—

Odds ratios Associated With Living in a Medical Marijuana State, by Age Group and Outcome: US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2004–2013

Note. OR = odds ratio.

**All ORs significant at P < .01; ***All ORs significant at P < .001.

In a final stage of the analysis, we controlled for state-level fixed effects. We used the medical marijuana indicator to measure within-state changes in attitudes; we controlled for cross-state differences with the state-level fixed effects. The addition of these fixed effects made it possible to rule out the possibility that unobserved state-level, time-constant confounders (e.g., more liberal social norms on drug use in medical marijuana states) account for the associations between living in a medical marijuana state and holding more permissive attitudes toward the drug.

Table 2 provides an excerpt of the results, which were similar across all age groups and outcomes (complete results available in Tables Q–CC as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Across all age groups, a time trend toward more permissive views became statistically significant in 2009, and for each subsequent year, the effect size grew larger. Although the time trend toward more permissive attitudes regarding marijuana remained present and statistically significant, the effects of living in a medical marijuana state were no longer statistically significant once we controlled for state-level fixed effects.

TABLE 2—

Excerpted Adjusted Odds Ratios Predicting Belief That Weekly Marijuana Use Is Not a Great Risk, Including Fixed Effects for State of Residence: US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2004–2013

| Variable | Middle School–Aged Youths, AOR (95% CI) | High School–Aged Youths, AOR (95% CI) | Young Adults, AOR (95% CI) |

| Medical marijuana state fixed effectsa | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.07) |

| Survey year fixed effectsb | |||

| 2004 (Ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2005 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) |

| 2006 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) |

| 2007 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | 1.12 (1.05, 1.19) |

| 2008 | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 1.05 (0.98, 1.13) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.29) |

| 2009 | 1.19 (1.08, 1.30) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.36) | 1.45 (1.36, 1.55) |

| 2010 | 1.31 (1.20, 1.44) | 1.41 (1.28, 1.56) | 1.66 (1.55, 1.79) |

| 2011 | 1.50 (1.36, 1.65) | 1.50 (1.39, 1.61) | 1.77 (1.66, 1.90) |

| 2012 | 1.25 (1.14, 1.37) | 1.46 (1.33, 1.60) | 2.00 (1.90, 2.10) |

| 2013 | 1.39 (1.29, 1.50) | 1.89 (1.70, 2.10) | 2.40 (2.25, 2.56) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. SEs are clustered at the state level. Results control for age-relevant controls at the individual level, controls at the state level, and fixed effects for the state of residence.

Dummy variables to indicate each year of data.

Dummy variables to indicate each state.

DISCUSSION

The United States is experiencing a wave of change leading to the relaxation of marijuana control policies—starting at the state level. Detractors raise concerns that, in passing medical marijuana laws, state policymakers could be sending “the wrong message” to young people—a message that minimizes the risks of using marijuana. We found that state medical marijuana laws are associated with more liberal attitudes among young people dwelling in medical marijuana states. This association was robust across 5 different measures of drug-related attitudes and 3 developmentally distinct age groups. Living in a medical marijuana state was associated with believing that monthly and weekly use of the drug is not a great risk, that cannabis is easy to obtain, and that parents and peers would not disapprove of its use.

Although we found robust evidence of an association between medical marijuana laws and more permissive views, our analysis failed to provide evidence of a causal relationship. When we controlled for state-level fixed effects, all associations between living in a medical marijuana state and holding permissive views on marijuana were nullified. This is consistent with the argument that the reason young people in medical marijuana states hold more permissive attitudes is not attributable to medical marijuana laws but rather reflects a more liberal orientation in states that pass medical marijuana laws. Our findings, therefore, do not support the conclusion that, in passing medical marijuana statutes, state policymakers are directly affecting the views of young people dwelling in their states.

Our analysis revealed strong evidence of a national trend toward more permissive attitudes about marijuana among young people. After controlling for state-level confounding variables, we found that young adults in 2013 had 2.4 times higher odds (CI = 2.25, 2.56) of reporting that the weekly use of marijuana is “not a great risk” than did young adults in 2004. Trends for high school–aged children (AOR = 1.89; CI = 1.70, 2.10) and middle school–aged children (AOR = 1.39; CI = 1.29, 1.50) were less pronounced but still statistically significant and meaningful from a public health standpoint. Notably, the national trend toward more permissive attitudes accelerated after 2009, coinciding with the rapid acceleration in successful movements to legalize marijuana for medical and recreational use. Young people today access most information through digital and social media, making it likely that drug policy discussions in 1 state will spill over into others. Therefore, although the enactment of state medical marijuana laws may not directly affect the views of young people living in those states, the symbolic influences accumulating across many states may add up to produce a national trend that is shifting norms among young people at the societal level.

As we hypothesized, the associations between medical marijuana laws and drug-related attitudes were more pronounced in older age groups. This underscores the importance of considering age-related variation in future studies of this kind. From a public health standpoint, different age groups pose different concerns for prevention. We found that children of middle school age uniformly held the least permissive views on marijuana and showed the weakest associations between attitudes and living in a medical marijuana state. This finding may indicate that drug prevention efforts targeting youths of high school age and young adults should be prioritized. The age at first use of illicit drugs is still among the strongest predictors of drug problems later in life,30 suggesting that younger age groups remain an important target population.

Limitations

We were not able to rule out the possibility that, over longer windows of time, state medical marijuana laws will exert causal impacts on the attitudes of young people dwelling in these states. We tested models using variables representing the length of time that each state’s medical marijuana law has been in place but found no statistically significant effects.31,32

There is also likely to be underreporting of permissive views on drugs because of social acceptability concerns and respondents’ fears of disclosure.33,34 The NSDUH used computer-assisted interviewing to increase the validity of self-reports consistently throughout the 10-year observation period. It is unlikely that underreporting varied across survey years, which was our focus.

It is also possible that our findings of age group differences were attributable to cohort effects. Age–period–cohort analyses have identified cohort differences in drug-related attitudes for Americans born before and after 1945.35 However, this would not explain the finer gradations of age group differentiations we found.

Conclusions

We did not find evidence that in passing medical marijuana laws state policymakers are directly affecting the views of young people living within their states. We did observe a national trend toward young people adopting more permissive views about marijuana that is occurring independently of any effects within states. This raises the possibility that the progressive liberalization of marijuana control policies at the state level has culminated in a national debate that is influencing all young Americans regardless of the states they dwell in. Our analysis also suggests that more permissive attitudes may be drivers in the liberalization of state marijuana control policies. As societal attitudes toward marijuana grow more permissive, this could add momentum to the further liberalization of marijuana control policies.

Throughout our analysis, we observed a consistent age gradient in shifting attitudes on marijuana, suggesting that children of middle school age may be more insulated from changing norms than are those of high school age and young adults. This was consistent with our hypothesis that older groups are more attuned and susceptible to the public policy discourse on liberalizing drug controls. Future studies should seek to better understand how state-level debates on relaxing marijuana control policies are reverberating at the national level and thus potentially reshaping the views of young people across the developmental spectrum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01 DA034091).

We would like to thank our colleagues who assisted in the data collection for and preparation of this article, including Timothy Bates, Krista Chan, Susan Chapman, Juliana Fung, Zachary Levin, and Jessica Lin. We would also like to acknowledge staff at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration and the University of Michigan for their assistance in data acquisition and management.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This project received approval from the University of California, San Francisco’s Committee on Human Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Senate Judiciary Committee. Prescription for Addiction? The Arizona and California Medical Drug Use Initiatives. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1996. CIS No. 97-S521-84. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, Drinking, and Drug Use in Young Adulthood: The Impacts of New Freedoms and New Responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Psychology Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandel D. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190(4217):912–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Explaining recent increases in students’ marijuana use: impacts of perceived risks and disapproval, 1976 through 1996. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):887–892. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Humphrey RH. Explaining the recent decline in marijuana use: differentiating the effects of perceived risks, disapproval, and general lifestyle factors. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29(1):92–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miech RA, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J, Patrick ME. Trends in use of and attitudes toward marijuana among youth before and after decriminalization: the case of California 2007–2013. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(4):336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palamar JJ, Ompad DC, Petkova E. Correlates of intentions to use cannabis among US high school seniors in the case of cannabis legalization. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Marijuana Decriminalization: The Impact on Youth 1975–1980. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khatapoush S, Hallfors D. “Sending the wrong message”: did medical marijuana legalization in California change attitudes about and use of marijuana? J Drug Issues. 2004;34(4):751–770. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuermeyer J, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Price RK et al. Temporal trends in marijuana attitudes, availability and use in Colorado compared to non-medical marijuana states: 2003–11. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;140:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(9):714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper S, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS. Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? Replication study and extension. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lac A, Crano WD. Monitoring matters meta-analytic review reveals the reliable linkage of parental monitoring with adolescent marijuana use. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2009;4(6):578–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandel D. Adolescent marihuana use: role of parents and peers. Science. 1973;181(4104):1067–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4104.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finney JW, Humphreys K, Harris AH. What ecologic analyses cannot tell us about medical marijuana legalization and opioid pain medication mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):655–656. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joffe A, Yancy WS American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Legalization of marijuana: potential impact on youth. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e632–e638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kandel DB. Drug and drinking behavior among youth. Annu Rev Sociol. 1980;6:235–285. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2011: Summary of National Findings. Ann Arbor, MI: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robins LN. The natural history of adolescent drug use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(7):656–657. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.POLIDATA. Demographic & political guides: political data analysis. Available at: http://www.polidata.org. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- 23.Chapman SA, Spetz J, Lin J, Schmidt LA, Chan K. Capturing heterogeneity in medical marijuana policies: a taxonomy of regulatory regimes across the United States. Subst Use Misuse. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2016.1160932. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stata Statistical Software, Release 14 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Person-Level Sampling Weight Calibration. Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers WH. Quantile regression standard errors. Stata Tech Bull 9. 1992;2:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wooldridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Froot KA. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with cross-sectional dependence and heteroskedasticity in financial data. J Financ Quant Anal. 1989;24(3):333–355. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Room R. Starting on the fringe: studying alcohol in a wet generation. In: Edwards G, editor. Addictions: Personal Influences and Scientific Movements. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1991. pp. 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore M, Gerstein D, editors. National Research Council. Alcohol and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow of Prohibition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babor TF, Brown J, Del Boca FK. Validity of self-reports in applied research on addictive behaviors: fact or fiction? Behav Assess. 1990;12:5–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Midanik L. The validity of self-reported alcohol consumption and alcohol problems: a literature review. Br J Addict. 1982;77(4):357–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1982.tb02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age–period–cohort influences on trends in past year marijuana use in the US from the 1984, 1990, 1995 and 2000 National Alcohol Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(2–3):132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]