Abstract

Objectives. To compare access to care and perceived health care quality by insurance type among low-income adults in 3 southern US states, before Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

Methods. We conducted a telephone survey in 2013 of 2765 low-income US citizens, aged 19 to 64 years, in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas. We compared 11 measures of access and quality of care for respondents with Medicaid, private insurance, Medicare, and no insurance with adjustment for sociodemographics and health status.

Results. Low-income adults with Medicaid, private insurance, and Medicare reported significantly better health care access and quality than uninsured individuals. Medicaid beneficiaries reported greater difficulty accessing specialists but less risk of high out-of-pocket spending than those with private insurance. For other outcomes, Medicaid and private coverage performed similarly.

Conclusions. Low-income adults with insurance report significantly greater access and quality of care than uninsured adults, regardless of whether they have private or public insurance. Access to specialty care in Medicaid may require policy attention.

Public Health Implications. Many states are still considering whether to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and whether to pursue alternative models for coverage expansion. Our results suggest that access to quality health care will improve under the Affordable Care Act's coverage expansions, regardless of the type of coverage.

Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) aimed to increase the availability of health insurance for low-income Americans through expansion of Medicaid eligibility up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL),1 the US Supreme Court ruled that Medicaid expansion was optional for states.2 This left many states debating whether and how to expand insurance coverage for low-income residents. As of January 2016, 31 states have expanded Medicaid, whereas the remaining 19 states have not adopted Medicaid expansion.1 The implications of these decisions are particularly dramatic in the South, where only 6 of the 17 states (plus the District of Columbia) in the southern census region have expanded. Combined with high poverty and uninsured rates in the region, 80% of the more than 4 million uninsured adults excluded from the Medicaid expansion reside in the South.3

Previous research indicates that Medicaid expansion can improve access to care, self-reported health, and survival,4 but some contend that the program is substantially inferior to private insurance.5 In part because of this concern, several states—Arkansas, Iowa, and New Hampshire—have received approval for the so-called “private option,” using federal funds to purchase private health insurance for low-income adults,6–8 and other states are considering this approach in lieu of Medicaid expansion. In this context, a key question is how Medicaid and private coverage compare in their ability to provide access to care for low-income beneficiaries. Previous research that used national survey data offers some insights,9 but less attention has been paid to these issues within southern states, where the public health implications of the Medicaid expansion debate are largest.

Our study objective was to compare access to care and perceived health care quality for low-income adults with Medicaid versus other types of insurance coverage before the ACA’s coverage expansion in 3 southern states.

METHODS

Our study data come from a random-digit-dial telephone survey of US citizens aged 19 to 64 years living in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas, with family incomes below 138% of the FPL, corresponding to the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility guidelines. Interviews were completed in November and December 2013, before the ACA’s coverage expansions took effect. Respondents were contacted on landlines and cellular phones. Interviews were available in English or Spanish. The overall response rate was 26%, and all responses were weighted to state estimates for citizens aged 19 to 64 years with household incomes below 138% of FPL, from the 2012 American Community Survey. Further details on the survey methods have been published previously.10

Survey

We developed a 38-item survey that included questions about health care coverage, utilization, economic circumstances, health status, preventive care indicators, and perceptions of quality of care. We drew the wording of our survey items from previously validated surveys: the National Health Interview Survey, the American Community Survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. We also collected data on demographic and health characteristics. We assessed health insurance coverage by using state-specific names for Medicaid programs to assist respondents in recognizing their coverage: Medicaid in Arkansas, Kentucky Health or KenPAC in Kentucky, and STAR, STAR+PLUS, or STAR Health in Texas.

To create mutually exclusive coverage categories, we assigned each respondent a primary type of coverage by using the following hierarchy: private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and uninsured. In our primary model, we categorized dual-eligible respondents—those who receive coverage from both Medicare and Medicaid—as having Medicare because this is the primary payer for outpatient services; we also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which these respondents were treated as having Medicaid as their primary coverage (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We excluded individuals who reported only having a type of coverage besides private insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare from the sample because of the small number of respondents in that category (3%).

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Our study outcomes were not having a personal doctor, difficulty accessing primary care appointments, difficulty accessing specialist appointments, using the emergency department (ED) as a usual source of care, using the ED because of difficulty in getting a doctor’s appointment when needed, cost-related delays in seeking care, spending more than $500 out of pocket for medical care in the past year, spending more than $1000 out of pocket for medical care in the past year, having to borrow money or skip paying bills because of medical costs, and perceived overall health care quality.

We compared sample demographic and health characteristics across insurance coverage types with the χ2 test. Then we used logistic regression to compare outcomes for respondents with private insurance to those with Medicaid, Medicare, and no health insurance. We present both unadjusted and adjusted regression results. The multivariate model adjusted for sociodemographic and health status covariates that previous literature has suggested influence access to care, health service utilization, and perceptions of health care quality: age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, income, political affiliation, self-reported health status (fair or poor vs good, very good, or excellent), cell phone use, having any of the 9 chronic conditions assessed in the survey (Table 1), and state of residence. Using the MARGINS command in Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), we then converted these adjusted odds ratios (AORs) into predicted probabilities for each outcome, using the observed values for all covariates, to better convey the magnitude of differences across these coverage types after we accounted for other covariates. On average, Medicaid and Medicare respondents reported 2.02 and 2.34 diagnosed chronic conditions, respectively, compared with 0.94 among the privately insured and 1.09 among the uninsured.

TABLE 1—

Demographic and Health Status Characteristics of Survey Respondents in 2013 in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas

| Characteristic | Private Health Insurance (n = 792), % | Medicaid (n = 396), % | Medicare (n = 594), % | Uninsured (n = 983), % | Pa |

| Family income | < .001 | ||||

| < 50% of poverty | 19 | 48 | 32 | 35 | |

| 50%−100% of poverty | 33 | 35 | 41 | 39 | |

| 100%–138% of poverty | 42 | 11 | 20 | 19 | |

| Don’t know or refused | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |

| Female | 54 | 77 | 57 | 54 | < .001 |

| Age, y | < .001 | ||||

| 19–34 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 35–44 | 64 | 56 | 39 | 65 | |

| 45–54 | 17 | 23 | 13 | 20 | |

| 55–64 | 17 | 21 | 48 | 14 | |

| Race/ethnicity | .01 | ||||

| Non-Latino White | 60 | 62 | 62 | 63 | |

| Latino | 16 | 16 | 10 | 18 | |

| Non-Latino Black | 18 | 20 | 25 | 16 | |

| Other Non-Latino | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Education | < .001 | ||||

| < high school | 11 | 36 | 31 | 25 | |

| High-school graduate | 41 | 44 | 47 | 43 | |

| Some college or college graduate | 48 | 20 | 22 | 32 | |

| Marital status | < .001 | ||||

| Married or living with a partner | 53 | 31 | 29 | 39 | |

| Single | 34 | 32 | 38 | 39 | |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 13 | 37 | 33 | 22 | |

| State | .01 | ||||

| Arkansas | 25 | 14 | 17 | 44 | |

| Kentucky | 28 | 13 | 17 | 42 | |

| Texas | 36 | 12 | 12 | 40 | |

| Rural status | 36 | 44 | 43 | 42 | .1 |

| Presence of ≥ 1 diagnosed condition (out of 9)b | 54 | 81 | 84 | 57 | < .001 |

| Self-reported fair or poor health | 25 | 50 | 54 | 36 | < .001 |

Note. The sample size was n = 2765.

P values reflect χ2 test for differences in each characteristic, based on coverage type.

Conditions assessed were high blood pressure; a heart attack, coronary artery disease, or heart failure; a stroke; asthma, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or emphysema; chronic kidney disease or dialysis; diabetes; depression or anxiety; cancer, except for skin cancer; and alcoholism or drug addiction.

RESULTS

Our sample size was 2765, divided evenly across the 3 states. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and health characteristics of respondents, stratified by primary coverage type. In our weighted sample, 13% reported Medicaid coverage, 30% private coverage, 16% Medicare, and 41% were uninsured. Women represented just over half of the sample overall, but made up 77% of those with Medicaid. A total of 16% of the overall sample was Latino and 19% was Black. Health status characteristics differed significantly across different insurance types. Of privately insured respondents, 25% reported fair or poor health status, compared with 50% of Medicaid respondents and 54% of Medicare respondents. More than 80% of Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries reported at least 1 chronic condition, compared with 54% to 57% among privately insured or uninsured respondents.

Table 2 shows unadjusted analyses assessing the association between coverage type and access to outpatient care, ED use, affordability of care, and perceived quality of care. Uninsured respondents consistently reported worse outcomes. In the unadjusted models, Medicaid beneficiaries had more difficulty accessing primary and specialty care, and were more likely to use the ED because a doctor was unavailable, compared with their privately insured peers. Medicaid beneficiaries were significantly less likely to have high out-of-pocket medical costs than privately insured adults. This was consistent at both levels of spending we assessed: spending greater than $500 per year (16.6% vs 37.7%; odds ratio [OR] = 0.33; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.21, 0.51; P < .01) and spending greater than $1000 per year (9.7% vs 24.5%; OR = 0.33; 95% CI = 0.19, 0.57; P < .01). A slightly larger share of respondents with Medicaid rated care as fair or poor than did those with private insurance, although this finding was not statistically significant (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 0.99, 2.05; P < .10).

TABLE 2—

Unadjusted Association of Access to Care and Quality of Care by Insurance Type in 2013 in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas

| Private (Ref) |

Medicaid |

Medicare |

Uninsured |

|||||

| Outcome | OR | Mean, % | OR (95% CI) | Mean, % | OR (95% CI) | Mean, % | OR (95% CI) | Mean, % |

| Access to outpatient care | ||||||||

| No personal doctor | 1 | 36.9 | 0.68 (0.45, 1.01) | 28.4 | 0.51 (0.35, 0.75) | 23.2 | 2.89 (2.19, 3.82) | 62.8 |

| Difficulty accessing primary care appointment | 1 | 11.1 | 1.92 (1.16, 3.19) | 19.5 | 0.79 (0.47, 1.35) | 9.1 | 2.46 (1.67, 3.61) | 23.6 |

| Difficulty accessing specialist appointment | 1 | 9.7 | 2.54 (1.54, 4.19) | 21.5 | 1.50 (0.91, 2.49) | 13.9 | 2.14 (1.43, 3.23) | 18.7 |

| ED use | ||||||||

| ED as usual location of care | 1 | 4.1 | 0.50 (0.19, 1.34) | 2.1 | 1.16 (0.47, 2.88) | 4.7 | 4.97 (2.60, 9.53) | 17.4 |

| Use of ED when doctor not available | 1 | 8.0 | 2.37 (1.37, 4.11) | 17.2 | 1.48 (0.87, 2.52) | 11.5 | 2.56 (1.62, 4.03) | 18.3 |

| Affordability and cost of care | ||||||||

| Delayed care because of cost | 1 | 25.0 | 1.32 (0.89, 1.97) | 30.6 | 0.90 (0.63, 1.29) | 23.1 | 3.49 (2.60, 4.69) | 53.8 |

| Delayed medication because of cost | 1 | 26.7 | 1.56 (1.08, 2.27) | 36.3 | 1.10 (0.79, 1.53) | 28.6 | 2.26 (1.69, 3.00) | 45.2 |

| > $500 out-of-pocket spending in past year | 1 | 37.7 | 0.33 (0.21, 0.51) | 16.6 | 0.57 (0.41, 0.79) | 25.6 | 0.79 (0.59, 1.05) | 32.2 |

| > $1000 out-of-pocket spending in past year | 1 | 24.5 | 0.33 (0.19, 0.57) | 9.7 | 0.61 (0.42, 0.88) | 16.5 | 0.97 (0.71, 1.32) | 23.9 |

| Delayed paying bills because of medical costs | 1 | 31.3 | 1.33 (0.92, 1.93) | 37.7 | 1.21 (0.88, 1.68) | 35.6 | 1.99 (1.51, 2.64) | 47.6 |

| Self-reported fair or poor quality of care | 1 | 38.1 | 1.43 (0.99, 2.05) | 46.8 | 0.82 (0.59, 1.14) | 33.5 | 2.57 (1.92, 3.43) | 61.3 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; ED = emergency department; OR = odds ratios from multivariate logistical regression (private insurance was the reference group for all ORs). The sample size was n = 2765.

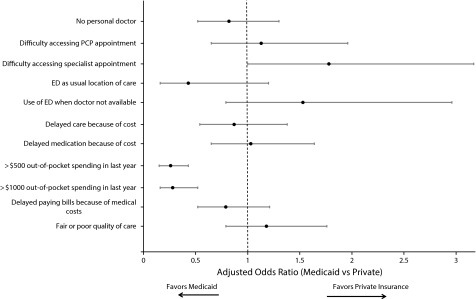

Table 3 shows the results of multivariate analyses. We have summarized the adjusted results in Figure 1, which illustrates ORs and 95% CIs when we specifically compared our outcomes of interest for Medicaid beneficiaries and the privately insured. After we adjusted for sociodemographics and health status, uninsured individuals were at significantly higher risk of not having a personal doctor and to report difficulty accessing primary care and specialty care. When we compared predicted probabilities from the adjusted model, similar rates of those covered by private insurance (35.5%), Medicaid (31.8%), and Medicare (31.7%) reported not having a personal doctor; this was markedly higher for uninsured respondents (59.0%), a difference of more than 20 percentage points (AOR = 3.07; 95% CI = 2.24, 4.19; P < .01). Overall, Medicaid and private insurance performed similarly for most measures of access to outpatient care, although individuals with Medicaid had higher rates of difficulty accessing specialist appointments relative to their privately insured peers—17.3% versus 11.1% after adjustment (AOR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.00, 3.17; P < .05).

TABLE 3—

Adjusted Association of Access to Care and Quality of Care by Insurance Type in 2013 in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas

| Private (Ref) |

Medicaid |

Medicare |

Uninsured |

|||||

| Outcome | AOR | PP, % | AOR (95% CI) | PP, % | AOR (95% CI) | PP, % | AOR (95% CI) | PP, % |

| Access to outpatient care | ||||||||

| No personal doctor | 1 | 35.5 | 0.82 (0.52, 1.30) | 31.8 | 0.82 (0.55, 1.24) | 31.7 | 3.07 (2.24, 4.19) | 59.0 |

| Difficulty accessing primary care appointment | 1 | 13.4 | 1.13 (0.65, 1.96) | 14.7 | 0.64 (0.36, 1.16) | 9.3 | 2.11 (1.41, 3.15) | 23.3 |

| Difficulty accessing specialist appointment | 1 | 11.1 | 1.78 (1.00, 3.17) | 17.3 | 1.26 (0.71, 2.24) | 13.3 | 2.01 (1.30, 3.10) | 18.9 |

| ED use | ||||||||

| ED as usual location of care | 1 | 4.4 | 0.43 (0.16, 1.20) | 2.0 | 1.40 (0.57, 3.45) | 5.9 | 4.54 (2.46, 8.40) | 15.9 |

| Use of ED when doctor not available | 1 | 9.4 | 1.53 (0.79, 2.96) | 13.4 | 1.21 (0.67, 2.16) | 11.0 | 2.32 (1.41, 3.81) | 18.4 |

| Affordability and cost of care | ||||||||

| Delayed care because of cost | 1 | 27.7 | 0.87 (0.54, 1.38) | 25.2 | 0.69 (0.45, 1.06) | 21.6 | 3.79 (2.72, 5.28) | 54.9 |

| Delayed medication because of cost | 1 | 30.1 | 1.03 (0.65, 1.64) | 30.7 | 0.73 (0.49, 1.10) | 25.0 | 2.45 (1.76, 3.40) | 46.8 |

| > $500 out-of-pocket spending in past year | 1 | 38.3 | 0.26 (0.16, 0.43) | 15.7 | 0.41 (0.28, 0.60) | 22.1 | 0.81 (0.59, 1.12) | 34.2 |

| > $1000 out-of-pocket spending in past year | 1 | 24.7 | 0.28 (0.16, 0.52) | 9.2 | 0.48 (0.32, 0.73) | 14.3 | 1.04 (0.74, 1.47) | 25.3 |

| Delayed paying bills because of medical costs | 1 | 35.4 | 0.79 (0.52, 1.22) | 31.0 | 0.87 (0.60, 1.26) | 32.7 | 1.90 (1.39, 2.58) | 48.4 |

| Self-reported fair or poor quality of care | 1 | 40.7 | 1.18 (0.79, 1.76) | 44.5 | 0.75 (0.51, 1.10) | 34.5 | 2.28 (1.67, 3.12) | 59.7 |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratios from multivariate logistical regression (private insurance was the reference group for all AORs); CI = confidence interval; ED = emergency department; PP = predicted probability, calculated from the logistic regression estimates by using Stata’s MARGINS command with default settings, which holds all covariates at their actual values. The sample size was n = 2765. Models controlled for insurance type, age, gender, marital status, education level, race/ethnicity, income, rural versus urban residence, cell phone use, political affiliation, self-reported fair or poor health, presence of chronic conditions, and state of residence.

FIGURE 1—

Association of Access to Care and Quality of Care Variables and Having Medicaid vs Private Insurance in 2013 in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Texas

Note. ED = emergency department; PCP = primary care physician. The sample size was n = 2765. Adjusted odds ratios for Medicaid from multivariate logistical regression. Private insurance was the reference group for all odds ratios. Models controlled for insurance type, age, gender, marital status, education level, race/ethnicity, income, rural versus urban residence, cell phone use, political affiliation, self-reported fair or poor health, presence of chronic conditions, and state of residence.

For measures of ED use, uninsured respondents were significantly more likely than insured respondents to use the ED as a usual location of care or visit the ED because of an inability to see a doctor for an office visit to address needed care. There were no significant differences between Medicaid and private insurance for these measures.

When we assessed affordability and cost of care, uninsured individuals were significantly more likely to report delaying care because of cost in the past 12 months, skipping medication doses because of cost, and borrowing money or skipping paying bills as a result of high medical costs compared with those with insurance. Meanwhile, there were no significant differences for any of these outcomes between Medicaid beneficiaries and privately insured persons. Medicaid beneficiaries were significantly less likely to have spent more than $1000 in out-of-pocket costs for medical care in the past year than individuals with private insurance—9.2% versus 24.7%, respectively (AOR = 0.28; 95% CI = 0.16, 0.52; P < .01). Results were similar when we compared out-of-pocket costs greater than $500 for Medicaid beneficiaries and privately insured individuals (15.7% vs 38.3%; AOR = 0.26; 95% CI = 0.16, 0.43; P < .01). Medicare recipients also were less likely to report high out-of-pocket costs than those with private insurance (14.3% vs 24.7%; AOR = 0.48; 95% CI = 0.32, 0.73; P < .01).

In terms of overall quality of care, uninsured adults were the most likely to rate their care as fair or poor. Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in the proportion reporting fair or poor quality of care among individuals with private coverage and Medicaid (AOR = 1.18; 95% CI = 0.79, 1.76; P = .41). Those with Medicare reported the highest quality of care, with only 34.5% reporting fair or poor quality of care.

DISCUSSION

In this survey of nearly 3000 low-income US citizens in 3 southern states, we found that, before the ACA’s coverage expansions, measures of access to care, affordability, and self-rated health care quality were generally similar for Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance, after we adjusted for demographic characteristics and health status. Consistent with previous research, all 3 coverage types performed far better than being uninsured for all outcomes we analyzed.11,12 In contrast, there were few significant differences among the 3 types of insurance covered. These results build off a previous study in these states, which focused on perceptions of Medicaid coverage compared with the private option among low-income adults in general (including among those with neither type of insurance). That study showed that low-income adults generally perceive private coverage and Medicaid as similar in overall quality.10 In our study, in contrast, we assessed the actual experiences obtaining care among low-income adults with different types of coverage, and we found that, in these states, public and private insurance perform similarly.

In unadjusted analyses, there were notable differences in health care–related outcomes for Medicaid beneficiaries versus privately insured individuals. However, these results in isolation can lead to the spurious conclusion that Medicaid provides inferior access to care than private coverage, when our multivariate analysis demonstrates that most of these differences are attributable to underlying demographic and health status differences. More specifically, the typical Medicaid beneficiary (or nonelderly Medicare beneficiary) is often in much worse health on average than those with private insurance or no insurance, which is not surprising given that disability and poverty are 2 of the primary pathways for nonelderly adults to become eligible for public insurance in the first place.

However, we did find 2 areas with significant differences between Medicaid and private coverage, even after multivariate adjustment: (1) Access to specialty care for individuals in Medicaid was worse than for those with private insurance, and (2) Medicaid provided better financial protection to low-income adults than private insurance.

The finding regarding specialty care access mirrors the results of a recent national analysis of Medicaid, which indicated similar access to primary care services for low-income adults with private insurance and Medicaid, but worse specialty-care access for those with Medicaid.13

The ACA prioritized improving access to primary care, mandating that states increase Medicaid primary care payments to Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014 to increase provider ability and willingness to accept new Medicaid patients.14–16 However, we did not find that Medicaid beneficiaries in these states had more difficulty obtaining primary care appointments or a usual source of care. Instead, we found worse access to specialty care for Medicaid beneficiaries compared with the privately insured. This could be attributable to a low number of specialists participating in Medicaid, specialist shortages in certain regions, or primary care physicians having limited referral networks for specialists.17 Surveys of providers indicate that the predominant deterrent for specialist participation in Medicaid is low payment rates, although patient complexity also plays a role.17–19

Although many Medicaid patients rely on safety net providers such as community health centers for primary care, there is often no comparable option for specialty care, particularly for specialty mental health or substance abuse services.20 This is an area worthy of ongoing evaluation and monitoring by policymakers. There were significant differences in specialty access between private and Medicaid recipients in our study, but it is worth noting that the vast majority of Medicaid recipients did not experience any difficulties in this area, with only 17% reporting this barrier in adjusted models.

Meanwhile, we found that Medicaid provided better financial protection to low-income adults than private insurance, consistent with previous research on the topic of underinsurance among poor adults.21 Medicaid beneficiaries were far less likely to spend more than $1000 out of pocket for medical costs than those with private coverage—and alternative analyses using different cutoff points for spending showed a similar pattern. More states, particularly those with Section 1115 waivers, are beginning to require higher levels of cost sharing for Medicaid beneficiaries, which may have an impact on the affordability of care for these low-income Americans.22,23 Previous studies have indicated that low-income Americans enrolled in public insurance tend to fare significantly better on affordability-related measures than those with private coverage as a result of higher premiums, deductibles, and cost sharing in private insurance plans—and recent trends suggest that this divergence in coverage generosity is continuing to grow over time.24

For the remaining outcomes we examined, we found no significant differences between Medicaid and private insurance. Although previous studies, including the randomized Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, indicate that gaining Medicaid coverage can increase ED use,25,26 our survey results indicate that Medicaid beneficiaries are using ED services in patterns fairly similar to low-income adults with private insurance.

Overall self-reported quality of health care received was also comparable for those enrolled in Medicaid and private insurance. The research literature has had little evidence to date on how quality of care for Medicaid beneficiaries compares with that of the privately insured from the patient’s perspective. A recent Gallup poll indicated that 75% of Medicaid beneficiaries are satisfied with the US health system, which was 6 percentage points higher than those with employer-sponsored coverage (69%) and 10 points higher than those with private coverage purchased directly from an insurer (65%), belying the argument from some critics of Medicaid that it is low-quality and undesirable coverage.27

Our study contains several limitations in design, response rate, and generalizability. To more closely parallel eligibility criteria for Medicaid and other public programs (including the ACA’s 2014 Marketplaces), we excluded from our sample noncitizen immigrants, who are represent a sizable minority of low-income uninsured adults in several southern states, including Texas. Although noncitizens with permanent residency status can qualify for Medicaid after a 5-year waiting period, there are challenges to reliably assessing noncitizens’ legal status in a telephone survey, so we did not attempt to include this group in our sample.

The majority of those reporting private coverage had employer-sponsored insurance. There is substantial heterogeneity in insurance plan design across employer-sponsored insurance plans and non–employer-based plans, including benefits and cost-sharing. Nonetheless, it seems reasonable to assume that employer-sponsored coverage is generally closer in design to “private option” plans than Medicaid—and in some states, private option proposals are explicitly using premium support for employer-based coverage.28

Data for this study were self-reported, which can result in some degree of misreporting error, particularly for items related to health status or clinical conditions. Previous research indicates that some degree of misreporting error in self-reporting insurance coverage status is common, especially for Medicaid.29,30 Our use of state-specific names for Medicaid programs may have reduced this problem to some degree.

In addition, although our response rates compare favorably to other random-digit-dial surveys, such as the Gallup Healthways Well-Being Index or the Health Reform Monitoring Survey, they were still much lower than federal government surveys.31,32 To address this limitation, we weighted our results to Census demographic benchmarks, which has been shown to mitigate nonresponse bias, although this does not necessarily eliminate all potential bias.33 It is unclear what impact—if any—nonresponse bias may have had on our results.

Our study also relies on multivariate regression to adjust for substantial differences across the populations in each type of coverage. This creates 2 potential concerns. The first is that the groups in different coverage categories may differ on unobservable features for which we were unable to adjust and thus may still confound our results. For instance, people with private insurance are more likely to be working, and we did not have data on employment status. Nonetheless, previous research indicates that most Medicaid beneficiaries have at least 1 working family member, suggesting that employment alone is not a primary distinguishing factor between these 2 coverage groups.34

A second concern is that adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics—including race/ethnicity, education, or socioeconomic status—overlooks underlying public health problems, and can render important differences in access to care and quality of care on the basis of those characteristics as either acceptable or undetectable. In a sensitivity analysis, we adjusted only for clinical factors: age, gender, self-reported health status, and presence of chronic conditions. The patterns for Medicaid versus private insurance in this analysis (presented in Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) were very similar as in our fully adjusted model. This suggests that the gaps between Medicaid beneficiaries and those with private insurance in our unadjusted analyses were primarily related to health status and disease burden, rather than sociodemographic features.

Lastly, our study was limited to 3 states, potentially reducing generalizability at the national level. However, these 3 states contain a diverse population of low-income adults in the Southern census region, a region of significant policy relevance for the ACA. In light of the disproportionate presence of millions of uninsured low-income adults in southern states and the ongoing policy debate about whether and how to expand coverage under the ACA, we feel that these states provide valuable new information on the experiences of low-income adults with difference types of health insurance.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

For most measures of access, adults enrolled in Medicaid fared similarly to their privately insured peers, after we accounted for differences in demographics and baseline health status. As many southern states continue to evaluate if and how to provide health insurance for low-income adults, policymakers are considering increasing their states’ reliance on private coverage. Meanwhile, officials in some states that have already expanded Medicaid are now proposing to repeal or significantly modify the expansion, further raising the stakes for understanding the impact of these different types of coverage for low-income adults.35 Our results suggest that, although some tradeoffs in specialty access and affordability may exist between Medicaid and private insurance, coverage expansions to low-income adults will likely lead to substantial gains in overall access to quality health care, regardless of whether that coverage is private or public insurance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by a research grant from The Commonwealth Fund and a career development grant (K02HS021291) from the Agency on Healthcare Research and Quality.

Note. B. D. Sommers currently serves part time as an advisor in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the US Department of Health and Human Services. The views presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Health and Human Services, Agency on Healthcare Research and Quality, or The Commonwealth Fund.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The investigators only had access to de-identified data processed by the survey vendor after survey administration was complete, and the study protocol was exempted as non–human participant research by the Harvard institutional review board.

Footnotes

See also Galea and Vaughan, p. 1354.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid expansion, health coverage, and spending: an update for the 21 states that have not expanded eligibility. 2015. Available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-medicaid-expansion-health-coverage-and-spending-an-update-for-the-21-states-that-have-not-expanded-eligibility. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 3.Stephens J, Artiga S, Lyons B, Jankiewicz, Rousseau D. Understanding the effect of Medicaid expansion decisions in the South. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2471. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb S. Medicaid is worse than no coverage at all. Wall Street Journal. March 10, 2011. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704758904576188280858303612.html. Accessed March 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford M, McMahon SM. Alternative Medicaid Expansion Models: Exploring State Options. Trenton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser Family Foundation. An overview of actions taken by state lawmakers regarding the Medicaid expansion. 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/an-overview-of-actions-taken-by-state-lawmakers-regarding-the-medicaid-expansion. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Special terms and conditions, New Hampshire Health Protection Program Premium Assistance, Number 11-W-00298/1. 2015. Available at http://www.dhhs.state.nh.us/pap-1115-waiver/documents/pa_termsandconditions.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 9.Long SK, Stockley K, Grimm E, Coyer C. National findings on access to health care and service use for non-elderly adults enrolled in Medicaid. Washington, DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; 2012. MACPAC contractor report no. 2.

- 10.Epstein AM, Sommers BD, Kuznetsov Y, Blendon RJ. Low-income residents in three states view Medicaid as equal to or better than private coverage, support expansion. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(11):2041–2047. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christopher AS, McCormick D, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Bor DH, Wilper AP. Access to care and chronic disease outcomes among Medicaid-insured persons versus the uninsured. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):63–69. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommers BD, Gordon S, Somers S, Ingram C, Epstein AM. Medicaid on the eve of expansion: a survey of state Medicaid officials on the Affordable Care Act. Am J Law Med. 2014;40(2-3):253–279. doi: 10.1177/009885881404000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ku L, Jones K, Shin P, Bruen B, Hayes K. The states’ next challenge—securing primary care for expanded Medicaid populations. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):493–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long SK. Physicians may need more than higher reimbursements to expand Medicaid participation: findings from Washington State. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(9):1560–1567. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decker SL. The effect of physician reimbursement levels on the primary care of Medicaid patients. Rev Econ Househ. 207;5(1):95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommers AS, Paradise J, Miller C. Physician willingness and resources to serve more Medicaid patients: perspectives from primary care physicians. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2011;1(2):e1–e18. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.001.02.a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum S. Medicaid payments and access to care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(25):2345–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1412488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes KV, Bisgaier J, Lawson CC, Soglin D, Krug S, Van Haitsma M. “Patients who can’t get an appointment go to the ER”: access to specialty care for publicly insured children. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(4):394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(5):1459–1468. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magge H, Cabral HJ, Kazis LE, Sommers BD. Prevalence and predictors of underinsurance among low-income adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1136–1142. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2354-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMorrow S, Kenney GM, Anderson N et al. Trade-offs between public and private coverage for low-income children have implications for future policy debates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1367–1374. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saloner B, Sabik L, Sommers BD. Pinching the poor? Medicaid cost sharing under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1177–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1316370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N et al. Health benefits in 2015: stable trends in the employer market. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(10):1779–1788. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, Baicker K, Finkelstein AN. Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon’s Health Insurance Experiment. Science. 2014;343(6168):263–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1246183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung PT, Wiler JL, Lowe RA, Ginde AA. National study of barriers to timely primary care and emergency department utilization among Medicaid beneficiaries. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):4–10.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rifkin R. Americans with government health plans most satisfied. Gallup. November 6, 2015. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/186527/americans-government-health-plans-satisfied.aspx. Accessed November 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georgetown University, Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families. Medicaid Premium Assistance Programs: what information is available about benefit and cost-sharing wrap-around coverage? 2015. Available at: http://ccf.georgetown.edu/ccf-resources/medicaid-premium-assistance-programs-information-available-benefit-cost-sharing-wrap-around-coverage. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 29.Call KT, Davidson G, Davern M, Nyman R. Medicaid undercount and bias to estimates of uninsurance: new estimates and existing evidence. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(3):901–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davern M, Klerman JA, Baugh DK, Call KT, Greenberg GD. An examination of the Medicaid undercount in the Current Population Survey: preliminary results from record linking. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(3):965–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skopec L, Musco T, Sommers BD. A potential new data source for assessing the impacts of health reform: evaluating the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. Healthc (Amst) 2014;2(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Long SK, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S et al. The Health Reform Monitoring Survey: addressing data gaps to provide timely insights into the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(1):161–167. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. 2012. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/Assessing%20the%20Representativeness%20of%20Public%20Opinion%20Surveys.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 34.Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of the nonelderly with Medicaid by family work status. 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/distribution-by-employment-status-4. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- 35.Gerth J. Beshear slaps Bevin, defends Medicaid expansion. The Courier-Journal. September 22, 2015. Available at: http://www.courier-journal.com/story/politics-blog/2015/09/22/beshear-slaps-bevin/72612544. Accessed November 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]