Follow-up on: Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Hatzenbuehler ML, Newcomb ME. Envisioning an America without sexual orientation inequities in adolescent health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):218–225.

Fifteen years ago, I wrote an AJPH editorial titled “Why LGBT public health?” where I tried to explain the importance of addressing lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) health and health disparities related to sexual orientation and gender minority status.1 I was the Guest Editor for AJPH’s first issue dedicated to LGBT health in the Journal’s then 91-year-history. Back then, the public health audience was uninformed and often reluctant to engage with LGBT health issues other than AIDS. A lot has changed since then. AJPH has become a leader in advancing LGBT health research by regularly publishing innovative research and providing important knowledge to public health researchers and policymakers.

In that editorial (and elsewhere), I proposed, based on social and psychological theories on prejudice, stigma, and the role of the social environment and stress on health, that prejudice and stigma against LGBT people can lead to adverse health outcomes. I, and others, have noted that social disadvantages predispose LGBT people to minority stress, which, in turn, causes adverse health outcomes and health disparities.2,3 This proposal has since been studied and supported by numerous researchers.4

The LGBT community is diverse with regard to almost every characteristic other than sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression. Although we sometimes talk about an LGBT community, we should be more concerned about LGBT communities. Intersections of sexual orientation and gender identity by race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, geographic region, religiosity, among others, are the types of social contexts that impact LGBT lives and health.5 Still, I noted then, there is one characteristic that is shared across LGBT communities and it is what makes LGBT individuals a population of interest for public health research and intervention.

LGBT people share remarkably similar experiences related to stigma, discrimination, rejection, and violence across cultures and locales. In the United States, gay men and lesbians are subject to legal discrimination in housing, employment, and basic civil rights. Sodomy laws, which brand gays and lesbians as criminals in 16 states, are often the basis for harassment and discrimination. Transgender individuals are stigmatized, discriminated against, and ridiculed in encounters with even those entrusted with their care. LGBT people fare better in some areas (e.g., parts of the European Community) than in others, but they are still subject to persecution and discrimination in many regions of the world.1(p856)

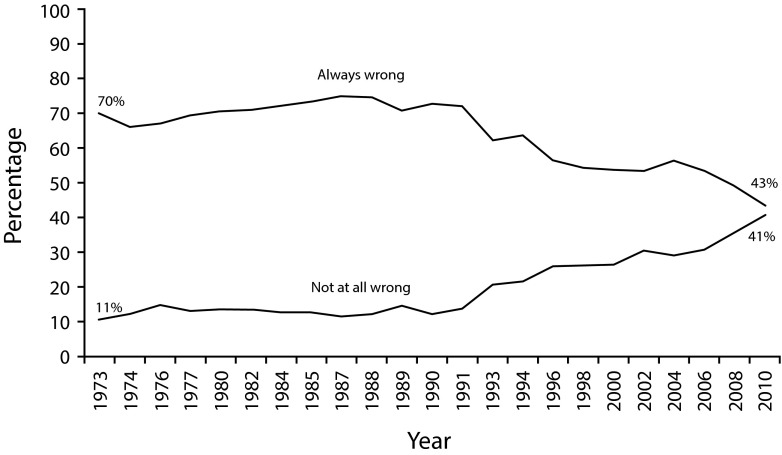

As we review these statements today, it is hard to not be impressed by the progress that we have witnessed in the United States in the 15 years since that publication: public opinion about homosexuality has shifted significantly over the past few decades, with more Americans than ever before saying that “sexual relations between two adults of the same sex” is “not at all wrong” (Figure 1); sodomy laws have been ruled unconstitutional in the United States; a Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy, which excluded sexual minorities from military service, has been repealed; and, perhaps most strikingly, same-sex couples are now recognized as equal to different-sex couples in marriage. In general, nationally, and globally, LGBT people are making headway toward gaining equal rights. (Although not the topic of this essay, it is important to be reminded here that LGBT people are subject to discrimination, persecution, and violence in many regions of the world.)

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of Americans Saying Sexual Relations Between 2 Adults of the Same Sex Are “Always Wrong” and “Not at All Wrong”: General Social Survey, United States, 1973–2010

Note. Chart by the author. Data source: Smith, T.W. (2011). Public Attitudes toward Homosexuality. Unpublished manuscript. NORC/University of Chicago.

These, along with other developments have led some researchers to suggest that the significance of anti-lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB)—and to a lesser extent antitransgender—stigma has declined.6 Consistent with minority stress and other social ecology theories, researchers predict that improvements in the social environment—a reduction in stigma and prejudice toward LGBT people—would lead to improved health outcomes and a reduction or even the elimination of health disparities.7

Indeed, evidence suggests that improvement in the social environment, especially for LGB people, has been followed by a related reduction in health disparities in areas of the United States where changes have been most pronounced. For example, Hatzenbuehler and colleagues have found that sexual minorities living in communities with better social environments (e.g., lower antigay prejudice, better legal protections for LGB people) have improved outcomes related to psychiatric disorders, suicide attempts, and all-cause mortality.7 Positive changes in the social environment are likely to make an impact on different generations of LGBT people across the life span, but it is especially significant for young people who, because they are socialized in a more positive social environment, can see a life trajectory that is more promising, especially in the area of intimacy and family life, than previous generations of LGBT people imagined.8

Despite this promise, however, we are yet to see the elimination of health disparities by sexual orientation (population research on gender minorities is still at its infancy). For example, research on millennial youths, the generation that has witnessed the most dramatic improvement in the social acceptance of sexual minorities, shows they have higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempt9—a finding that has persisted since researchers began to assess disparities in suicide in the 1980s.

LGBT advocates have focused on legal battles and legal victories—most notably, marriage equality. However, there are signs that suggest stigma and prejudice against LGBT people persist and sometimes evolve in different ways. For example, despite legal protections in marriage, LGBT people can be fired with impunity: while 21 states provide legal protections against employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, 29 states do not provide such protections. These 29 states cluster geographically in the Midwest, South, and Mountain states, leaving most LGBT citizens with limited legal options to address experiences of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in the workplace.5 Also, part of the response to the opening of marriage to same-sex couples has been increased rhetoric about “religious protections,” which the American Civil Liberties Union described as “using religion to discriminate against LGBT people.”10 This rhetoric has been followed by legislative and litigation attempts to allow, under the guise of religious freedoms, discrimination against LGBT people in employment, health, and provision of services such as lodging, purchasing wedding dresses, and photography.10

Moreover, it is important to remember that social equality is not synonymous with equality under the law. Minority stress—a cause of health disparities—is a theory about the impact of prejudice and stigma. Laws are a necessary foundation to achieve equality but, as we witness regarding race relations in the United States, protections under the law are not sufficient to eliminate prejudice. We have seen, for example, that racist ideologies persist even if racist acts become less socially acceptable and therefore somewhat less overt. As Figure 1 shows, tremendous progress has been made in acceptance of same-sex relationships in the United States, but still in 2010, only 41% of Americans said that such relationships are not at all wrong. It remains to be seen if general prejudice and stigma related to sexual and gender minority status declines in concert with changes in attitudes toward specific issues, like marriage, or whether homophobia and transphobia get transformed into more palatable anti-LGBT attitudes such as is evident by the move toward supporting “religious freedoms.”

We live in an exciting time as we witness progress toward greater equality for sexual and gender minorities. But the changes we have witnessed are too limited and too recent to determine their impact on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. Public health research needs to continue to assess changes in stigma, prejudice, and attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities, as well as the impact of such changes—should they persist—on health and health disparities.

In a 2014 AJPH editorial titled, “Envisioning an America without sexual orientation inequities in adolescent health,” Mustanski et al. described their vision of social equality leading to the elimination of health disparities.7 To date, we have made some strong headway, but the vision laid out by the authors remains elusive.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work of the author was supported, in part, by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number R01HD078526).

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyer IH. Why lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender public health? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):856–859. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2012;43(5):460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 4.IOM (Institute of Medicine) The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasenbush A, Flores AR, Kastanis A, Sears B, Gates GJ. The LGBT divide: a data portrait of LGBT people in the Midwestern, Mountain & Southern states. 2014. Available at: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-divide-Dec-2014.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2016.

- 6.McCormack M. The Declining Significance of Homophobia: How Teenage Boys are Redefining Masculinity and Heterosexuality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Hatzenbuehler ML, Newcomb ME. Envisioning an America without sexual orientation inequities in adolescent health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):218–225. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost DM, Meyer IH, Hammack PL. Health and well-being in emerging adults’ same-sex relationships: critical questions and directions for research in developmental science. Emerg Adulthood. 2014;3(1):3–13. doi: 10.1177/2167696814535915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bostwick WB, Meyer I, Aranda F et al. Mental health and suicidality among racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youths. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Civil Rights Union. Using religion to discriminate. Available at: https://www.aclu.org/feature/using-religion-discriminate. Accessed March 14, 2016.