To the editor:

Since early April 2009, the world has been responding to a pandemic of a novel H1N1 influenza A virus (pH1N1). Data on transmission and severity of pH1N1, especially from the Southern Hemisphere will help plan for the upcoming Northern Hemisphere influenza season. In mid‐June 2009, the Naval Medical Research Center Detachment in Peru, the CDC and the Peruvian Ministry of Health implemented a prospective cohort population‐based study of influenza in Peru. We report the first 6 weeks of this population‐based data, specifically describing the evolution and clinical data of pH1N1. 343 households from San Juan de Miraflores District, Lima and their household members were randomly selected from a previous census list using a computer‐based, randomly generated numbers table and invited to participate in the study. Subsequently, field workers performed screening visits to households three times per week to identify influenza‐like illness (ILI) cases. The ILI case definition for individuals ≥5 years of age included sudden onset of fever >38°C, with cough and/or sore throat and for children <5 years old, we utilized the WHO‐ILI case 1 definition with the addition of rhinorrhea and/or nasal congestion. Once an ILI case was identified, both nasal and oropharyngeal swabs were collected, combined and placed into viral transport media, transported at 4°C to the laboratory and stored at −80°C. For each identified ILI case, multiple follow‐up site visits were conducted over a 15‐day period to determine clinical symptoms duration. Identification of pH1N1 was conducted using the CDC 2009 pH1N1 real‐time PCR (rRT‐PCR) assay, 2 while seasonal influenza A viruses were identified using standard rRT‐PCR procedures. Attack rates (AR) and incidence rates (IR) were estimated by age group for ILI and pH1N1 confirmed cases.

A total of 1747 individuals, living in 343 households, were enrolled in the study from May to June, 2009. Screening visits were initiated on June 25, 2009 and, as of August 1, 191 ILI cases had been identified.

Of the 191 ILI cases, 134 were positive (70·1%) for pH1N1 – only one seasonal H3N2 isolate was identified from samples negative for pH1N1. The percentage of ILI due to pH1N1 was highest in the age group of 5–17 years (86·2%) compared with other age groups (Table 1). The most common symptoms at illness onset among pH1N1 cases of all ages were cough (92·5%), rhinorrhea (77·6%), malaise (69·4%), sore throat (67·9%) followed by headache (64·9%), red eyes (47·8%), vomiting (25·4%), and diarrhea (9·7%). Median symptom duration among all pH1N1 cases that completed 15 days of follow‐up was cough 8 days (range 0–15 days), rhinorrhea 5 days (range 0–15 days), sore throat 2 days (range 0–12 days), fever 1 day (range 1–8 days), and headache 1 day (range 0–15 days). As of August 1 2009, the cumulative attack rate for confirmed pH1N1 infection among all ages was 7·7%. Age adjusted IRs of pH1N1 were slightly higher among young adults and children (Table 1) and were equivalent with respect to gender (data not shown), although few confirmed cases were identified among adults >50 years of age. Weekly incidence rates of pH1N1 ranged from 11·7 to 27·8 cases/1000 person‐weeks. We have begun to observe a reduction of pH1N1 IRs and ARs, as well as a reduction in ILI ARs over time (Table 1). By extrapolating from our population‐based data for pH1N1 (AR = 7·7%), we estimate that 3800 pH1N1 cases may have occurred among individuals in the study population and >300 000 cases among the population of Lima.

Table 1.

Influenza‐like illness (ILIs) and pandemic H1N1 influenza (pH1N1) attack rates and incidence rates between June 14th and August 1st, 2009

| Dates | Epi weeks | ILIs total (N = 191) | pH1N1 (N = 134) | Other etiologies (N = 57)† | No of pH1N1/ ILIs (%) | pH1N1 cumulative attack rate (%) | Other etiologies cumulative attack rate (%) | Weekly pH1N1 incidence rate × 1000 | Age specific weekly pH1N1 incidence rate × 1000 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5 (n = 196) | 5–9 (n = 160) | 10–17 (n = 315) | 18–29 (n = 478) | 30–49 (n = 402) | 50–59 (n = 133) | >=60 (n = 63) | |||||||||

| Jun 14–20 | Week 24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·06 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| Jun 21–27 | Week 25 | 29 | 20 | 9 | 68·97 | 1·15 | 0·57 | 11·45 | 5·10 | 50 | 28·57 | 2·09 | 0·00 | 7·52 | 0·00 |

| Jun 28–Jul 4 | Week 26 | 60 | 47 | 13 | 78·33 | 3·84 | 1·32 | 27·23 | 51·28 | 85·53 | 49·02 | 12·58 | 7·46 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| Jul 5–11 | Week 27 | 54 | 39 | 15 | 72·22 | 6·07 | 2·18 | 23·23 | 48·65 | 71·94 | 27·49 | 23·35 | 2·51 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| Jul 12–18* | Week 28 | 29 | 19 | 10 | 65·52 | 7·16 | 2·75 | 11·59 | 22·73 | 46·51 | 10·60 | 8·70 | 5·03 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

| Jul 19–25 | Week 29 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 50·00 | 7·50 | 3·09 | 3·70 | 5·81 | 8·13 | 7·14 | 2·19 | 0·00 | 7·58 | 0·00 |

| Jul 26–Aug 1 | Week 30 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 50·00 | 7·67 | 3·26 | 1·86 | 5·85 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 4·40 | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00 |

*School closing from July 15th to August 9th

†All tested for influenza A and B, one H3N2 identified

These data provide the first unbiased description of the epidemiology of pH1N1 from a developing country as compared with national surveillance data, as they are gathered from an active population‐based surveillance system. Incidence rates within the Lima population cohort clearly demonstrate that the epidemic of pH1N1 was well established in the greater population of Lima at the time of the study screening. Cumulative ARs of pH1N1 (7·7%) have been very similar to those reported from southern hemisphere countries, such as New Zealand (7·5%). 3 Furthermore, as with other countries, the ARs initially increased over time; however, these rates (both ILI and pH1N1) began to plateau during epidemiological weeks 29 and 30 (Table 1). As with other countries, pH1N1 IRs and ARs were highest in children <18 years old. This may suggest that children are either more susceptible to infection with pH1N1, as compared with adults, or perhaps that their social network and/or behavior contributed to a higher risk of infection. As others have speculated, perhaps older populations, including those of Lima, have a partial protection to this novel strain. 4 Follow‐up serological surveys may help clarify these findings. Our data demonstrate that the clinical symptoms and duration for pH1N1 infection are similar to what has been described for normal seasonal influenza illness. 5 In slight contrast to the findings of Dawood et al, 6 we identified a lower proportion of diarrhea among pH1N1 confirmed cases (9·7% vs. 25%).

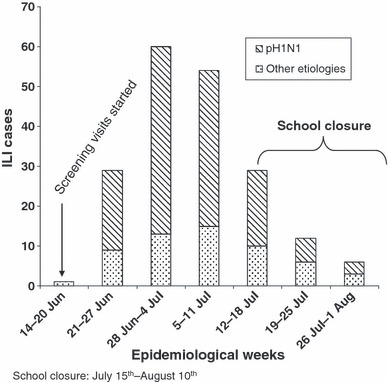

Mitigation strategies, such as educational campaigns and airport screening of incoming foreign passengers, and discouraging mass gatherings, were implemented in mid‐April in Lima. Although these sorts of efforts have been shown to be useful in minimizing dissemination of influenza in other countries, and likely did so in Peru, these initial strategies did not prevent the spread of pH1N1 among the general population of Lima. Conversely, school closures may have helped to reduce the IRs and ARs of pH1N1 and ILI, respectively, among school aged children; however, it is also possible that school closures may have been implemented after most children had been ill, as rates in this population were already beginning to decline (Figure 1 and Table 1, [link]). Additional weeks of surveillance and further studies (i.e., serological surveys) will help to address these questions. Alternatively, our results may reflect the early phase of this pandemic in Peru, with rapid transmission among children and young adults related to school contact and social behavior, with delayed spread among older adults. 7

Figure 1.

pH1N1 Epidemiological curve between June 14th and August 1st 2009 in Lima, Peru.

Many investigators have suggested that 11–35% of outpatient ILI cases, globally, are due to seasonal influenza A and B viruses. 8 , 9 , 10 As a result, one important question that arises is whether or not pH1N1 will displace seasonal influenza viral strains. Although our data are limited by short time period, most ILI cases had laboratory‐confirmed pH1N1 during the typical winter influenza season in Lima, 70·1% in total, with very little seasonal influenza virus circulation within this population. As mentioned previously, individuals <18 years of age in our population had the highest proportion of pH1N1 as an etiologic agent of ILI (86·2%), opposed to what is normally observed in a prepandemic influenza season, whereby in this age group influenza virus is not the most common cause of respiratory illness. 11 , 12 These data may suggest a trend in displacement of seasonal influenza by pH1N1 as has been observed in other countries, including those in the Southern Hemisphere, 13 , 14 during this same period of time. 15 Additional weeks of surveillance will help to clarify this finding.

Epidemiologic data on the impact of pandemic influenza from the Southern Hemisphere winter may help inform planning for the upcoming Northern Hemisphere influenza season. Data generated by this population‐based study has allowed calculation of measures of disease impact for a larger population. Such data may help inform pH1N1 mitigation strategies, surveillance strategies, and vaccine policy.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the US Government.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health – Fogarty International Center and the US DoD Global Emerging Infections Systems grant number I0082_09_LI. The Naval Medical Research Center participation was under Protocol NMRCD.2009.0005 in compliance with all applicable Federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects.

Disclosure

None of the authors has a financial or personal conflict of interest related to this study. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit this publication.

Copyright statement

Joel M. Montgomery, Tadeusz J. Kochel and Tim Uyeki are U.S. military and public health service members; Marc‐Alain Widdowson and V. Alberto Laguna‐Torres are employees of the US Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. § 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government’. Title 17 U.S.C. § 101.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank numerous contributors to this study including the influenza staff from the Lima‐Peru influenza cohort site and Lilia Cabrera; Merly Sovero, Josefina Garcia and Gloria Chauca of the US NMRCD Virology Department; and finally the community members of San Juan de Miraflores District.

Peru Influenza Working Group: V. Gonzaga, H.H. Garcia, A.E. Gonzalez, M.J. Sklar, B. Ghersi, J. Neyra, D. Vera, R. Hora, C. Romero, A. Estela, P. Breña, M. Morales.

References

- 1. WHO . WHO Recommended Surveillance Standards, 2nd edn 1999. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/surveillance/WHO_CDS_CSR_ISR_99_2_EN/en/ (Accessed 9 October 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . CDC Protocol of Realtime RTPCR for Influenza A(H1N1). 2009. Available at http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/CDCRealtimeRTPCR_SwineH1Assay‐2009_20090430.pdf (Accessed 27 July 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker MG, et al. Pandemic influenza A(H1N1)v in New Zealand: the experience from April to August 2009. Euro Surveill 2009; 14:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. CDC . Serum cross‐reactive antibody response to a novel influenza A(H1N1) virus after vaccination with seasonal influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58:521–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. CDC . Influenza: The Disease. 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/index.htm (Accessed 30 October 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dawood FS, et al. Emergence of a novel swine‐origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2605–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glezen WP, et al. Mortality and influenza. J Infect Dis 1982; 146:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monto AS, Sullivan KM. Acute respiratory illness in the community. Frequency of illness and the agents involved. Epidemiol Infect 1993; 110:145–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simmerman JM, Uyeki TM. The burden of influenza in East and South East Asia: a review of the English language literature. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2008; 2:81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laguna‐Torres VA, et al. Influenza‐like illness sentinel surveillance in Peru. PLoS ONE 2009; 4:e6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fabbiani M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical study of viral respiratory tract infections in children from Italy. J Med Virol 2009; 81:750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Arruda E, et al. Acute respiratory viral infections in ambulatory children of urban northeast Brazil. J Infect Dis 1991; 164:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CDC . Surveillance for the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus and seasonal influenza viruses‐New Zealand, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58:918–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelly H, Grant K. Interim analysis of pandemic influenza (H1N1) 2009 in Australia: surveillance trends, age of infection and effectiveness of seasonal vaccination. Euro Surveill 2009; 14:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. WHO . Preparing for the Second Wave: Lessons from Current Outbreaks. Global Alert and Response (GAR). 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_second_wave_20090828/en/index.html (Accessed 28 August 2009). [Google Scholar]