Abstract

We examined the relationship between collective self-esteem (i.e., the value one places on being part of a collective group), acculturation, and alcohol-related consequences in a sample of 442 Asian American young adults. We found that membership self-esteem and public collective self-esteem interacted with acculturation such that low levels of both predicted greater rates of consequences. Participants with lower acculturation and greater private collective self-esteem experienced more alcohol consequences. This study suggests that differential aspects of collective self-esteem may serve as protective or risk factors for Asian American young adults depending on degree of acculturation.

Keywords: Asian American, young adults, alcohol, consequences, acculturation, collective self-esteem

Alcohol use and related consequences are increasing concerns in the Asian American community. Although recent epidemiological data suggest Asian American young adults have lower current alcohol use relative to other ethnic groups (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008), rates of alcohol use among Asian American young adults and adolescents appear to be increasing and comparable with those of the adult population (Grant et al., 2004; So & Wong, 2006; Wechsler, Dowdall, Maenner, Gledhill-Hoyt, & Lee, 1998). In addition, the rate of alcohol abuse among 18 to 29 year old Asian women increased significantly between 1991–1992 and 2001–2002, with alcohol dependence among Asian men of the same age also increasing significantly over the 10-year period (Grant et al., 2004). These results underscore the need to understand risk and protective factors for problematic alcohol use among Asian American youth and young adults.

Several risk and protective factors for alcohol use among Asian American youth have been examined, including community (e.g., availability of drugs), family (e.g., family conflicts), school (e.g., lack of commitment to school), and peer (e.g., friends who engage in problem behavior) variables (Harachi, Catalano, Kim, & Choi, 2001). Individual-level variables such as religious affiliation (Luczak, Corbett, Oh, Carr, & Wall, 2003), genotype deficiency (Doran, Myers, Luczak, Carr, & Wall, 2007; Wall, Shea, Chan, & Carr, 2001), masculine norms (Liu & Iwamoto, 2007), and Asian values and acculturation (Hahm, Lahiff, & Guterman, 2003, 2004; Hendershot, Dillworth, Neighbors, & George, 2008; Hendershot, MacPherson, Myers, Carr, & Wall, 2005) have also been examined. Less explored in the literature on Asian American youth are the individual level variables associated with outcomes of negative health behaviors (e.g., consequences resulting from consuming alcohol). Because young adults represent a population particularly sensitive to peer influence and social comparison, as well as a group developing a self-identity while exploring risky behaviors such as drug use and sexual activity (Arnett, 2004), identification with the ethnic group one belongs to may have a relationship with alcohol-related consequences. Thus, within a college population in particular, identification with an ethnic group (and one’s perceptions about how others view this ethnic group) may have an effect on one’s drinking-related behaviors. This identification has been conceptualized as collective self-esteem (Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992).

COLLECTIVE SELF-ESTEEM AND DRINKING AMONG ASIAN AMERICAN YOUTH AND YOUNG ADULTS

Based on social-identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), part of one’s self-concept is construed by the membership one has in social groups and the connection one has to those groups. Within the model of ethnicity, Luhtanen and Crocker (1992) suggested that collective self-esteem contained four facets: membership self-esteem (i.e., judgment of one’s worth as a member of their ethnicity), private collective self-esteem (i.e., evaluation of the worth of one’s own ethnicity), public collective self-esteem (i.e., evaluation of how others view the worth of one’s ethnicity), and importance to identity (i.e., how important being a member of one’s ethnicity is to one’s self-concept). In general, the available research with Asian American samples suggests that collective self-esteem relates to greater well-being, whereas lower collective self-esteem relates to negative health outcomes. For example, with the exception of importance to identity, the other three collective self-esteem facets positively and significantly correlated with measures of life satisfaction and general self-efficacy, and negatively and significantly correlated with measures of depression and hopelessness among samples of Asian American college students (Crocker, Luhtanen, Blaine, & Broadnax, 1994; Kim & Omizo, 2005).

Among similar samples of Asian American young adult college students, aspects of collective self-esteem have been found to be negatively related to career selection and decision making difficulties, interpersonal consequences (e.g. difficulty relating to others), and self-esteem difficulties (e.g., feeling void of talents and strengths) (Liang & Fassinger, 2008). Lower levels of public collective self-esteem (i.e., belief others view one’s Asian ethnicity poorly) are associated with greater acculturative stress (Kim & Omizo, 2005), which has been found to be a major predictor of negative health outcomes (Hwang & Ting, 2008; Thomas & Choi, 2006). Although prior research with Asian American young adults has evaluated the relationship between well-being and facets of collective self-esteem (Crocker et al., 1994; Kim & Omizo, 2005), we are not aware of any published research examining the relationship between collective self-esteem and drinking outcomes. Perhaps closest to the concept of well-being, consequences resulting from alcohol use may be an important outcome to examine in this population.

ACCULTURATION AND DRINKING

Because measures of collective self-esteem deal with one’s identity as a collective social being, it may be important when examining these facets among collectivist cultures (e.g., individuals with Asian ethnic identification) to include measures of acculturation. Higher adherence to Asian values (e.g., collectivism, conformity to norms) is significantly associated with facets of collective self-esteem (i.e., membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, importance to identity) among Asian American college students (Kim & Omizo, 2005). The relationship between acculturation, defined as the adaption of the worldviews and living patterns of a new culture (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001), and alcohol use among Asian American youth and young adults is a complicated phenomenon. Theoretical models have frequently regarded acculturation as a cause of stress and impaired mental and behavioral health among ethnic minorities (O’Nell & Mitchell, 1996; Organista, Organista, & Kurasaki, 2002; Wolsko, Mohatt, Lardon, & Burket, 2009). Consistent with these models, several studies indicated that acculturation was positively associated with alcohol consumption (Hahm et al., 2003, 2004; Nakashima & Wong, 2000; Sue, Zane, & Ito, 1979; Zane, Park, & Aoki, 1999). For example, higher acculturation to American culture was significantly associated with higher alcohol consumption among a sample of Chinese and Filipino youth aged 12 to 18 years (Zane et al., 1999). However, one recent study found that lower acculturation among Korean college students was associated with greater drinks on peak occasion and greater number of hours spent drinking on a typical weekend evening (Hendershot et al., 2008).

These findings indicate that one’s degree of acculturation would likely affect the relationship between facets of collective self-esteem and alcohol-related consequences. It is possible that an individual who views his or her group negatively (or feels left out of the group) and displays a low level of acculturation (e.g., struggles connecting with the American culture) would experience alcohol-related consequences. This marginalization (i.e., feeling of not fitting into either culture) has been linked to mental health problems among Asian American young adults and adolescents (Furnham & Li, 1993; Giang & Wittig, 2006; Ying, 1995).

THE CURRENT STUDY

The current study addressed gaps in the research literature by examining the relationship between collective self-esteem factors (i.e., membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, public collective self-esteem, importance to identity), acculturation, and alcohol-related consequences among a large sample of Asian American young adults. Consequences resulting from alcohol use was chosen as the outcome most related to well-being. We drew from the literature on collective self-esteem and well-being for hypotheses because we are not aware of any available research to generate confident empirical hypotheses for collective self-esteem facets and this outcome. First, it was hypothesized that greater levels of collective self-esteem would predict fewer alcohol-related consequences among Asian American students. In addition, because acculturation is an important concept in both alcohol and self-esteem research among Asian Americans, we explored acculturation as a moderator between facets of collective self-esteem and alcohol-related consequences. It was hypothesized that lower levels of acculturation would interact with lower collective self-esteem to yield the greatest number of consequences.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were part of a larger alcohol intervention study, and data for the current manuscript were obtained from the screening and baseline surveys prior to the intervention (Larimer et al., 2011). Participants were from two West Coast universities: one large public and one small mid-sized private university. Screening criteria for inclusion in the longitudinal trial, which includes the baseline survey, included self-reporting as either Asian or Caucasian ethnicity and drinking at least four drinks of alcohol for women or five or more drinks for men (N = 1,948) on one occasion during the past month. The current study involves secondary data analyses of the Asian participants in this larger study who completed both screening and baseline surveys (n = 442). Mean age of these participants was 20.06 years (SD = 1.40 years), and 54% were women (n = 239). The majority of participants were enrolled in college full-time (97%) and were spread across four class years: 15% freshmen, 24% sophomores, 24% juniors, 37% seniors. Specific Asian ethnicity of the sample included 30% identifying with Chinese ethnicity, 25% Korean, 12% Vietnamese, 10% Filipino, 8% Japanese, 5% Taiwanese, 3% Asian Indian, and 7% other Asian ethnicities.

Design and Procedure

All measures and procedures were approved by the human subject review committee at each university. All invited participants received e-mail and mailed invitations to complete a Web-based screening survey. Prior to beginning the screening survey, participants read an informed consent statement and electronically provided consent. Those who completed the screening survey and met inclusion criteria were invited to the baseline survey. In the baseline survey, participants completed questions regarding demographics, typical weekly drinking, acculturation, and collective self-esteem. Participants were instructed to use random PIN codes for confidential survey completion.

Measures

Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences

Typical weekly drinking in the past month was assessed with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Participants indicated how many drinks they typically consumed on each night of a typical week in the past month. A typical drinks per week variable was computed by summing the typical amount consumed during each day of the week in the past month. Alcohol-related consequences were assessed with the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) (White & Labouvie, 1989). Participants were asked to indicate the frequency with which they experienced each of 25 alcohol related consequences in the past month. Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (more than 10 times). Two questions were added to the original 23-item RAPI assessing driving after drinking either two or more drinks or four or more drinks. A problems in the past month variable was created by summing the responses to the 25 items. Reliability of the scale was adequate, α = .92.

Acculturation

Acculturation level was assessed using the Suinn-Lew Asian Self Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA) (Suinn, Ahuna, & Khoo, 1992), which contains 21 items with response options from 1 (greater identification with Asian culture) to 5 (greater identification with Western culture). A higher composite mean score reflects greater Western identification (i.e., high acculturation), whereas a lower composite score reflects greater identification with Asian culture (low acculturation). Reliability of the scale was adequate (α = .91).

Collective self-esteem

The Collective Self-esteem Scale (Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992) was used to assess the value participants placed on being a member of their ethnic group. The measure contains four subscales: membership self-esteem (e.g., “I am a worthy member of my race/ethnic group”), private collective self-esteem (e.g., “I feel good about the race/ethnicity I belong to”), public collective self-esteem (e.g., “Overall, my racial/ethnic group is considered good by others”), and importance to identity (e.g., “The racial/ethnic group I belong to is an important reflection of who I am”). Participants were asked to consider their own race/ethnicity when rating 16 items from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Each subscale contains four items, and the mean of these four items yields a score for that subscale. The Collective Self-esteem Scale has demonstrated adequate construct validity in both predominantly White samples (Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992) and diverse samples with African American/Black and Asian American samples (Crocker et al., 1994). Reliability estimates for the four subscales (membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, public collective self-esteem, importance to identity) in the current sample were α = .78, .85, .78, and .79, respectively.

RESULTS

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were structured around predicting scores on the alcohol-related consequences scale from acculturation and the collective self-esteem facets (membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, public collective self-esteem, and importance to identity) after controlling for level of alcohol consumption (i.e., typical drinks per week in the past month) and sex. Variance in body weight, sex, and genetic reactions to alcohol among Asian American students makes alcohol use an important factor to control for in analyses. Regression analyses were completed based on a Poisson distribution as the dependent variable was positively skewed (Klein, 1998). The method used is considered preferable over data transformations in regression analyses (Atkins & Gallop, 2007). Poisson regression provides log-based parameter estimates, which can be otherwise interpreted similarly to traditional parameter estimates. Alcohol-related consequences were specified as the dependent variable. Predictors included sex (coded men = 0, women = 1), typical drinks per week in the past month, acculturation, and the four collective self-esteem facets, as well as the four product terms representing interactions between acculturation and each of the four collective self-esteem subscales. Typical drinks per week in the past month, acculturation, and the collective self-esteem subscales were all mean centered to facilitate interpretation of interactions and to reduce non-essential multicollinearity (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2002). Parameter estimates can be interpreted as the percentage change in expected counts (Atkins & Gallop, 2007). For example, for each unit increase in acculturation we would predict 1% fewer consequences. Similarly, for each unit increase in membership self-esteem, we would predict 8% fewer consequences. Positive coefficients represent percentage increases; for example, each unit increase in drinking predicted a 3% increase in the rate of consequences. Coefficients for interaction terms are similar to traditional regression analyses in that they represent predicted changes in one coefficient based on the other but again for percentage change in expected counts.

Descriptive analyses

Table 1 displays means and standard deviations for the dependent variable (RAPI score) and independent variables (collective self-esteem facets, acculturation, and typical drinks per week in the past month). A correlation matrix for all variables is also contained in Table 1. Mean scores for each of the collective self-esteem subscales corresponded to an agree response. Participants were also slightly more oriented toward Asian culture according to the SL-ASIA, with a score of 3 indicating the mid-point between Asian and Western (1) cultural orientation. Drinking significantly and positively correlated with alcohol-related consequences and acculturation, such that a higher orientation toward Western culture associated with greater drinking levels.

TABLE 1.

Means and Standard Deviations in a Correlation Matrix for Collective Self-Esteem, Alcohol Use and Consequences, and Acculturation

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Typical drinks per weeka |

– | ||||||

| 2. Consequences past monthb |

0.34** | – | |||||

| 3. Membership self-esteem |

0.06 | −0.12* | – | ||||

| 4. Private collective self-esteem |

0.08 | −0.12* | 0.66** | – | |||

| 5. Public collective self-esteem |

0.08 | −0.08 | 0.51** | 0.56** | – | ||

| 6. Importance to identity |

0.06 | −0.02 | 0.51** | 0.53** | 0.28** | – | |

| 7. Acculturationc | 0.14** | −0.01 | −0.32** | −0.13** | 0.02 | 0.31** | – |

| Mean | 8.57 | 4.09 | 5.14 | 5.60 | 5.31 | 4.84 | 3.18 |

| Standard Deviation | 8.13 | 7.00 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.95 | 1.23 | 0.58 |

Daily Drinking Questionnaire.

Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index score.

Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Predicting alcohol-related consequences

The overall model predicting alcohol-related consequences was significant (log-likelihood Chi-square [df = 11] = 528.09, p < .001). Regression coefficients from analyses can be found in Table 2. As would be expected, results revealed a strong effect for typical drinks per week on consequences. There was no difference in alcohol-related consequences between men and women after accounting for typical drinks per week in the past month, collective self-esteem, and acculturation. A main effect of acculturation revealed that, on average, increased acculturation was associated with fewer consequences when controlling for drinking and collective self-esteem. Main effects for three of four collective self-esteem subscales (membership self-esteem, private collective self-esteem, public collective self-esteem) were significant. Whereas membership self-esteem and public collective self-esteem were each negative predictors of consequences, greater reported private collective self-esteem predicted consequences. Importance to identity was not significantly associated with alcohol-related consequences.

TABLE 2.

Poisson Regression Results Evaluating Alcohol-Related Consequences in the Past Month as a Function of Collective Self-Esteem and Acculturation, Controlling for Drinking and Sex

| Parameter | B | Self-esteem B | EXP B | Wald Chi-Square (df = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical drinks per weeka | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 273.73*** |

| Sex (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.92 | 2.36 |

| Membership self-esteem | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 100.93*** |

| Private collective self-esteem | 0.08 | 0.01 | 1.08 | 38.14*** |

| Public collective self-esteem | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 8.79** |

| Importance to identity | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.78 |

| Acculturationb | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 13.70*** |

| Acculturation X membership self-esteem |

0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 63.31*** |

| Acculturation X private collective self-esteem |

−0.01 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 61.41*** |

| Acculturation X public collective self-esteem |

0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 11.68** |

| Acculturation X importance to identity |

0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.09 |

Typical drinks per week (in the past month) computed from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire.

Acculturation computed from the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Scale.

p < .01,

p < .001.

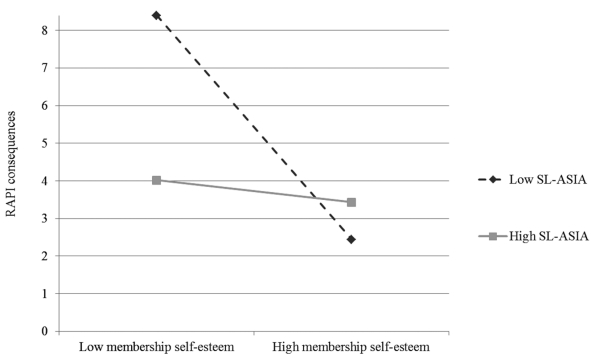

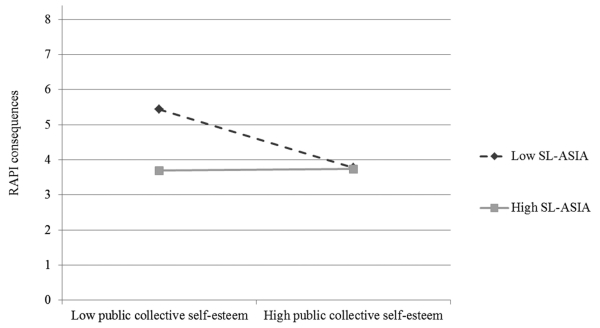

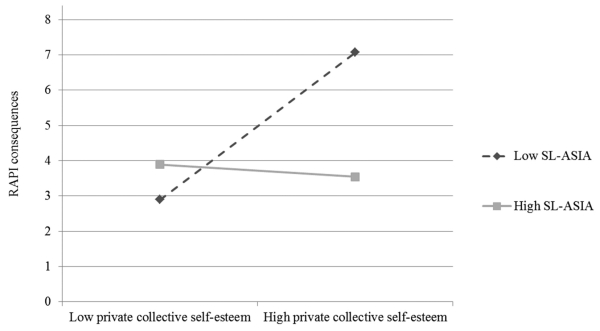

Main effects of collective self-esteem were qualified by interactions with acculturation for membership, public collective, and private collective self-esteem. Each of the main effects was most evident among those who were lower in acculturation. Figure 1 presents predicted scores for consequences, derived from the Poisson regression equation, at high and low values of membership self-esteem, which were specified as one standard deviation above and below the mean respectively (Cohen et al., 2002). Figure 1 indicates that acculturation moderated the relationship between membership self-esteem and consequences such that those lower in both acculturation and membership self-esteem experienced the greatest level of alcohol-related consequences. A similar pattern was evident for the interaction between acculturation and public collective self-esteem (Figure 2). Conversely, acculturation moderated the relationship between private collective self-esteem and consequences such that those lower in acculturation but higher in private collective self-esteem experienced the greatest level of alcohol-related consequences (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Interaction between acculturation and membership self-esteem predicting alcohol-related consequences.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction between acculturation and public collective self-esteem predicting alcohol-related consequences.

FIGURE 3.

Interaction between acculturation and private collective self-esteem predicting alcohol-related consequences.

DISCUSSION

The current study built on limited prior research related to alcohol use and consequences among Asian American college students, showing that acculturation and collective self-esteem are important constructs related to alcohol-related consequences. Findings from this study revealed that membership self-esteem, private collective, and public collective self-esteem significantly predicted alcohol-related consequences among a large sample of Asian American young adult students. Although membership self-esteem and public collective self-esteem were negatively predictive of consequences, private collective self-esteem was positively predictive of consequences. Participants who did not feel like a worthy member of their ethnicity (low membership self-esteem), believed that others viewed their ethnic group less favorably (low public collective self-esteem), and believed that their ethnic group was good (high private collective self-esteem) reported greater alcohol-related consequences. Importance to identity was not significantly associated with consequences. This is not a surprising finding given that this subscale did not have a strong relation with other mental health outcomes (e.g., depression) in prior research, where Crocker et al. (1994) suggested that well-being may be more related to evaluations of the group and the role one plays in them rather than how important the group is to one’s identity. A similar effect may exist for the alcohol-related consequences.

The relationships between domains of collective self-esteem and alcohol-related consequences were moderated by how acculturated young adults felt. Membership self-esteem was most negatively predictive of alcohol-related consequences for those with lower acculturation. That is, participants who identified less with the Western culture and who also felt as if they were not a worthy member of their ethnic group reported greater rates of alcohol consequences. A similar pattern was exhibited for the interaction between acculturation and public collective self-esteem in this sample of Asian American young adults. Identifying less with the worldview and living styles of the Western culture, coupled with lower evaluation of how others view the Asian ethnicity, predicted greater alcohol-related consequences. When ethnic minorities believe themselves to be unworthy members of their culture of origin (i.e., low membership self-esteem) and believe that the dominant society negatively evaluates the worth of their ethnicity (i.e., low public collective self-esteem), they may experience marginalization, or a sense of isolation from both their culture of origin and the dominant society (Berry, 1998, 2003). Marginalization has been associated with negative mental health outcomes (Furnham & Li, 1993; Ying, 1995) and predicted lower levels of public self-esteem among a diverse sample of high school students (Giang & Wittig, 2006). Consistent with these findings, Asian American young adults with lower levels of acculturation and lower membership self-esteem or public collective self-esteem may have used drinking as a negative coping strategy to deal with feelings of exclusion from both cultures. Drinking to cope has been linked to greater levels of alcohol-related consequences among college students (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Hasking, 2006; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005).

In addition to marginalization, racial discrimination may influence public collective self-esteem among the Asian Americans in the current study. Liang and Fassinger (2008) found that public collective self-esteem had a negative relationship with a measure of Asian American racism-related stress. The negative health impact of racial discrimination has been established among Asian Americans (Chae et al., 2008; Gee, Spencer, Chen, Yip, & Takeuchi, 2007). Thus, future research should examine the relationships between racial discrimination, public collective self-esteem, and alcohol-related consequences in the Asian American young adult population. This line of research may have implications for promoting equality and reducing alcohol-related consequences for Asian American and other ethnic minority young adults on college campuses.

The non-hypothesized relationship between private collective self-esteem and acculturation with alcohol consequences differed from membership self-esteem and public collective self-esteem. Specifically, the positive association between private collective self-esteem and alcohol-related consequences was most evident among those with lower acculturation. This finding suggests that young adult drinkers who have high regard for Asian ethnicity and are less adapted to the U.S. culture reported more alcohol-related consequences. It is possible that individuals who have a high regard for their Asian ethnicity but continue to drink heavily experience some distress due to deviating from Asian-appropriate drinking norms. That is, if one cares about their culture but continues to behave in inconsistent ways regarding that culture (i.e., drinking heavily), more consequences may be experienced than some-one who is following the flow of the mainstream cultural norms. In addition, although participants were asked to consider their ethnicity when asked about collective self-esteem items, it is possible that some participants may have also factored in their identity with an ethnic-specific heavy drinking group (e.g., Asian fraternity or sorority organizations). This may explain why those higher in private collective self-esteem (e.g., my Asian fraternity or sorority group is good) and lower acculturation (e.g., spending most of the time with heavy-drinking Asian peers) reported the most consequences. Unfortunately, this cannot be evaluated with the data available. Analyses with Greek and other subgroups could be considered in further research studies examining collective self-esteem, alcohol use, and peer groups.

Findings in this study offer several clinical implications. Asian American young adult drinkers with lower levels of acculturation (i.e., greater home cultural orientation) and greater private collective self-esteem (i.e., believed that Asian culture is positive) reported greater rates of alcohol-related consequences. These individuals may benefit from some form of substance abuse counseling but may be reluctant to seek such services due to stigma related to mental health counseling (Kim & Omizo, 2003). In general, Asian Americans are underrepresented in alcohol treatment centers and in-patient hospitalizations for alcohol or other drug use (Zane & Kim, 1994). Findings from the current study can help mental health professionals better understand how cultural factors can influence facets of negative well-being and potential reluctance to seek services to target these concerns. In addition, the current study found that Asian American young adults with lower levels of acculturation (i.e., greater home cultural orientation) and lower membership self-esteem (i.e., did not believe that they are a worthy member of the race/ethnic group) reported higher rates of alcohol-related consequences. Thus, it may be important for mental health professionals to encourage these individuals to get involved in local organizations serving Asian Americans (e.g., community center). For some Asian American young adults, these activities may enhance membership self-esteem, which in turn may reduce drinking-related consequences.

Limitations

The current study must be viewed in light of several limitations. First, the sample consisted of self-reported Asian American college students from two West Coast universities, both of which have relatively large proportions of Asian American students (approximately 25% and 33%, respectively). Thus, results may not generalize to other universities, particularly where Asian American students may be more in the minority on campus. Second, participants were all screened as heavy drinkers in the prior month with specific criteria. Further research should investigate the effect of acculturation and collective self-esteem in the initiation of and maintenance of alcohol use. Because the project was advertised as an alcohol study, it may have attracted young adults who were concerned about their alcohol use. Thus, findings may not generalize to those who were not concerned about their drinking. Finally, data were cross-sectional, and although theory and prior research suggest acculturation and collective self-esteem relate prospectively to indices of well-being it is possible that greater involvement in heavy drinking or greater experience of alcohol-related consequences may affect participants’ reports of collective self-esteem or acculturation. Additional longitudinal research is needed to address this question.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite limitations, the current research is a preliminary step toward understanding the potential role of acculturation and collective self-esteem in alcohol-related consequences of Asian American college students. Given the increasing diversity of U.S. demographics with growing representation of Asian-identified individuals (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004), as well as increasing risks for heavy and problem drinking among Asian youth and young adults in the United States (Grant et al., 2004; So & Wong, 2006), research evaluating risk and protective factors for alcohol consequences in this population has important implications for public health. Current results suggest the importance of considering both acculturation and specific aspects of collective self-esteem in understanding how interactions with the majority culture may influence the expression of alcohol consequences among Asian American youth and young adults.

Contributor Information

ERIC R. PEDERSEN, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

SHARON HSIN HSU, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

CLAYTON NEIGHBORS, University of Houston, Houston, Texas.

CHRISTINE M. LEE, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

MARY E. LARIMER, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

REFERENCES

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Re-thinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:725–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturative stress. In: Organista PB, Chun KM, Marin G, editors. Readings in ethnic psychology. Routledge; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Takeuchi DT, Barbeau EM, Bennett GG, Lindsey JC, Stoddard AM, et al. Alcohol disorders among Asian Americans: Associations with unfair treatment, racial/ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identification (the national Latino and Asian Americans study, 2002-2003) Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62(11):973–979. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression: Correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen R, Blaine B, Broadnax S. Collective self-esteem and psychological well-being among White, Black, and Asian college students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Myers MG, Luczak SE, Carr LG, Wall TL. Stability of heavy episodic drinking in Chinese- and Korean-American college students: Effects of ALDH2 gene status and behavioral undercontrol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:789–797. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Li YH. The psychological adjustment of the Chinese community in Britain: A study of two generations. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162:109–113. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer M, Chen J, Yip T, Takeuchi DT. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang MT, Wittig MA. Implications of adolescents’ acculturation strategies for personal and collective self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;62:725–739. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Guterman NB. Acculturation and parental attachment in Asian American adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Guterman NB. Asian American adolescents’ acculturation, binge drinking, and alcohol- and tobacco-using peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32:295. [Google Scholar]

- Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Kim S, Choi Y. Etiology and prevention of substance use among Asian American youth. Prevention Science. 2001;2(1):57–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1010039012978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasking PA. Reinforcement sensitivity, coping, disordered eating and drinking behaviour in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:677–688. [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Dillworth TM, Neighbors C, George WH. Differential effects of acculturation on drinking behavior in Chinese- and Korean-American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:121–128. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, MacPherson L, Myers MG, Carr LG, Wall TL. Psychosocial, cultural and genetic influences on alcohol use in Asian American youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:185–195. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W, Ting J. Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(2):147–154. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Omizo MM. Asian cultural values, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, and willingness to see a counselor. The Counseling Psychologist. 2003;31:343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Omizo M. Asian and European American cultural values, collective self-esteem, acculturative stress, cognitive flexibility, and general self-efficacy among Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Atkins AC, Lewis MA, et al. Descriptive drinking norms: For whom does reference group matter? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:833–843. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Fassinger R. The role of collective self-esteem for Asian Americans experiencing racism-related stress: A test of moderator and mediator hypotheses. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(1):19–28. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Iwamoto DK. Conformity to masculine norms, Asian values, coping strategies, peer group influences and substance use among Asian American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2007;8:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen R, Crocker J. A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Corbett K, Oh C, Carr LG, Wall TL. Religious influences on heavy episodic drinking in Chinese-American and Korean-American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:467–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima J, Wong MM. Characteristics of alcohol consumption, correlates of alcohol misuse among Korean American adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2000;30:343–359. doi: 10.2190/XV42-MW3U-VGY9-7M0X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nell TD, Mitchell CM. Alcohol use among American Indian adolescents: The role of culture in pathological drinking. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42:565–578. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista PB, Organista KC, Kurasaki K. The relationship between acculturation and ethnic minority mental health. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- So DW, Wong FY. Alcohol, drugs, and substance use among Asian American college students. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38:35–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Substance use among Asian youth. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k2/AsianYouthAlc/AsianYouthAlc.htm.

- Sue S, Zane N, Ito J. Alcohol drinking patterns among Asian and Caucasian Americans. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 1979;10:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Ahuna C, Khoo G. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale: Concurrent and factorial validation. Educational & Psychological Measurement. 1992;52:1041–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin W, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Brooks/Cole; Pacific Grive, CA: 1979. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Choi JB. Acculturative stress and social support among Korean and Indian immigrant adolescents in the United States. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 2006;23:123–143. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity—a supplement to mental health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau The American community-Asian: 2004. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/acs-05.pdf.

- Wall TL, Shea SH, Chan KK, Carr LG. A genetic association with the development of alcohol and other substance use behavior in Asian Americans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:173–178. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;47:57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie E. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolsko C, Mohatt GV, Lardon C, Burket R. Smoking, chewing, and cultural identity: Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use among the Yup’ik: The Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) Study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:165–172. doi: 10.1037/a0015323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y-W. Cultural orientation and psychological well-being in Chinese Americans. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:893–911. doi: 10.1007/BF02507020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane NW, Kim JC. Substance use and abuse. In: Zane NW, Takeuchi DT, Young KNJ, editors. Confronting critical health issues of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. pp. 316–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Park S, Aoki B. The development of culturally valid measures for assessing prevention impact in Asian American communities. In: Yee BWK, Mokuan N, Kim S, editors. The development of culturally valid measures for assessing prevention impact in Asian American communities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 61–89. DHHS Publication No. SMA 98-3193. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Berry JW. Psychological adaptation of Chinese sojourners in Canada. International Journal of Psychology. 1991;26:451–470. [Google Scholar]