Abstract

Efforts to ensure effective participation of patients in healthcare are called by many names—patient centredness, patient engagement, patient experience. Improvement initiatives in this domain often resemble the efforts of manufacturers to engage consumers in designing and marketing products. Services, however, are fundamentally different than products; unlike goods, services are always ‘coproduced’. Failure to recognise this unique character of a service and its implications may limit our success in partnering with patients to improve health care. We trace a partial history of the coproduction concept, present a model of healthcare service coproduction and explore its application as a design principle in three healthcare service delivery innovations. We use the principle to examine the roles, relationships and aims of this interdependent work. We explore the principle's implications and challenges for health professional development, for service delivery system design and for understanding and measuring benefit in healthcare services.

Keywords: Healthcare quality improvement, Health professions education, Patient-centred care, Social sciences, Health services research

“The physician,” wrote Hippocrates, “must not only be prepared to do what is right [himself,] but also make the patient…cooperate.”1 For centuries, traditional medical culture has recognised that some sort of patient partnership is essential. Recently, this partnership has received increasing attention. The Institute of Medicine named patient-centred care one of the six fundamental aims of the US healthcare system.2 Empirical evidence suggests that informed, activated patients may be effective in facilitating good health outcomes at lower cost.3 Payers seek healthcare consumer evaluation of patient experience in their endeavour to measure and pay for value.4 The US Center for Medicare Services identifies patient and family engagement as a pillar in its efforts to improve healthcare.5

Contemporary dialogue about patient-centred care, however, seems compromised by an implicit paradigm, which suggests that healthcare service is a product manufactured by healthcare systems for use by healthcare consumers. This product paradigm may confound efforts to put patients and professionals in right relationship. Healthcare service is better conceived as a service. Services, unlike manufactured goods, are always coproduced by service professionals and service users.

Even in the most traditional model of medical practice—patient comes to clinician for help, clinician listens to and examines the patient, clinician formulates a plan and instructs the patient, patient follows (or does not follow) suggestions—health outcomes (good and bad) are coproduced. Good outcomes, most recognise, are more likely if the patient can and does seek and receive help in a timely way, if the clinician and patient communicate effectively, develop a shared understanding of the problem and generate a mutually acceptable evaluation and management plan. The degree to which patients and professionals each hold agency for these coproduced outcomes varies widely, but the observation that health outcomes are a consequence of the dispositions, capacities and behaviours of both parties seems self-evident. Deceptively obvious, the concept has profound implications for improving healthcare quality, safety and value.

The theory of coproduced services in economics, political science and business

Victor Fuchs noted in 1968 that the new service economy (eg, retail, banking, education, healthcare) was distinct from the old industrial economy (manufacturing, agriculture); services entail a different relationship between producer and consumer. Measuring productivity in the service economy, he noted, was challenging because consumers and providers of services always work together to create value.6

Over the next decade, political scientists and sociologists explored public service coproduction in police and fire protection, sanitation and education.7–10 Citizens, they observed, coproduce public good by locking doors, installing security systems and fire alarms, reporting suspicious activity, sorting garbage and hauling it to the curb and participating in parent–teacher associations. Recognising this coproduction of public good, they noted, had implications for defining roles and responsibilities of citizens and public officials. Ostrom expanded the concept to groups of consumers and chains of suppliers and producers and recognised that civil servants and citizens have many (sometimes complex and conflicting) motivations to coproduce public services.11

In 1980, Alvin Toffler described a new generation of increasingly sophisticated and technologically enabled consumers as ‘prosumers’ capable of linking previously separated functions of production and consumption in ways that maximise consumer convenience and minimise producer cost.12 Familiar examples include at-home pregnancy tests, cake mixes, self-service gas stations and automated bank tellers. The ongoing digital revolution in the decades since Toffler wrote continues to blur the boundary between producer and consumer in almost relentless innovation.

Richard Normann further developed service coproduction.13 The word consume, he noted, has two Latin roots—‘to destroy or use up’ and ‘to complete or perfect’. Using the second meaning, consumers are consummators that can and do create value at every stage in business during research and development, design, production and delivery, monitoring and evaluating quality. He described a “service logic” that replaces the “oversimplified view that producers satisfy needs and desires of customers” with the “more complex view that they together form a value-creating system” (Norman,13 p. 98). Business offerings, using this logic, are not outputs of the business, but rather inputs for consumers’ processes of value creation. He distinguished a ‘relieving’ service logic and an ‘enabling’ service logic. In ‘relieving’ work, a professional creates value by doing something for the consumer that the professional is better equipped to do. In ‘enabling’ work, a professional creates value by expanding the scope of what a consumer can do.

The theory of coproduced services in public services administration

During the last two decades, scholars from multiple disciplines have explored the implications of ‘coproduction’. Voices from the fields of history,14 restorative justice,15 ergonomics,16 higher education,17 social policy and governance,18 19 environmental management,20 land use and animal farming21 and urban planning22 have joined the conversation and expanded our understanding of the idea. In this article, we invite particular attention to the possible utility of the idea for healthcare service and healthcare service improvement. As such, the conceptual development of the idea from the domain of public services administration and management is particularly relevant.23–27

Building on the distinctions between the production of goods and the production of services articulated above, Vargo and Lusch describe the differences between a ‘goods-dominant logic’ in public administration management theory and a ‘service-dominant logic’.28 Osborne summarises three key distinguishing features of services that inform this need for a service-dominant logic in management theory: (1) a product is invariably concrete, while a service is an intangible process; (2) unlike goods, services are produced and consumed simultaneously and (3) in services, users are obligate coproducers of service outcomes.29 Radnor et al17 note that public management theory, despite its service core, consistently draws upon generic management theory derived from the goods-dominant logic of manufacturing. We believe her insight applies to healthcare services and healthcare service improvement as well, where improvement methodologies and frameworks (such as Lean and Six Sigma) developed in manufacturing often dominate.

Though a comprehensive review is beyond the scope of this paper, governments have increasingly called for more explicit attention to facilitating partnership between professionals and beneficiaries in coproducing public services.17–19 23–25 Loeffler et al30 note several motives for this movement. More effective partnership in these coproduced services, they posit, might improve public services by (1) employing the expertise of service users and their networks; (2) enabling more differentiated services and more choice for service users; (3) increasing responsiveness to dynamic user need and (4) reducing waste and cost. We suspect that we might further the same aims by advancing a more explicit commitment to facilitating effective coproduction in healthcare services.

Coproducing healthcare services

Several have previously suggested bridges between healthcare service and the construct of coproduction.31–35 In describing the Scottish commitment to advancing effective coproduction in social and healthcare service, Loeffler et al30 note that the construct is far-reaching and includes potential partnership between health professionals and patients (or people seeking help to maximise their health and wellbeing) at many levels: (1) co-commissioning of services, which includes coplanning of health and social policy, coprioritisation of services and cofinancing of services; (2) codesign of services; (3) codelivery of services, which includes comanaging and coperforming services and (4) coassessment, which includes comonitoring and coevaluation of services. They describe the Scottish Co-production Network that provides a forum for shared learning about the practice of coproduction in social and healthcare services.

The Loeffler frame has direct relevance to the design and delivery of public health services and healthcare services for populations. To the extent that healthcare service also includes the intimacy of interactions at the bedside or in the examination room, however, the construct of coproduction in healthcare service is even more complex. Indeed, many have called for improved partnership between patients and clinicians using different nomenclature—shared decision making,36 patient engagement,37 patient activation,38 relationship-centred care.39 Bates and Robert have articulated a framework they call experience-based codesign that invites focused attention to the lived experiences of patients, families and health professionals and encourages collaborative work on healthcare system redesign.40 Increasing attention to the importance of self-care and self-management in healthcare services also contributes to our understanding of the dynamics of effective partnership for coproducing good outcomes.41 42 Some have already expressed concern about the implications of the coproduction construct for healthcare service and pointed to the way in which poor health compromises one's ability to engage in true partnership, and to the complex ways in which payers and regulatory bodies shape and constrain coproductive interactions between health professionals and patients.43 44

A conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction

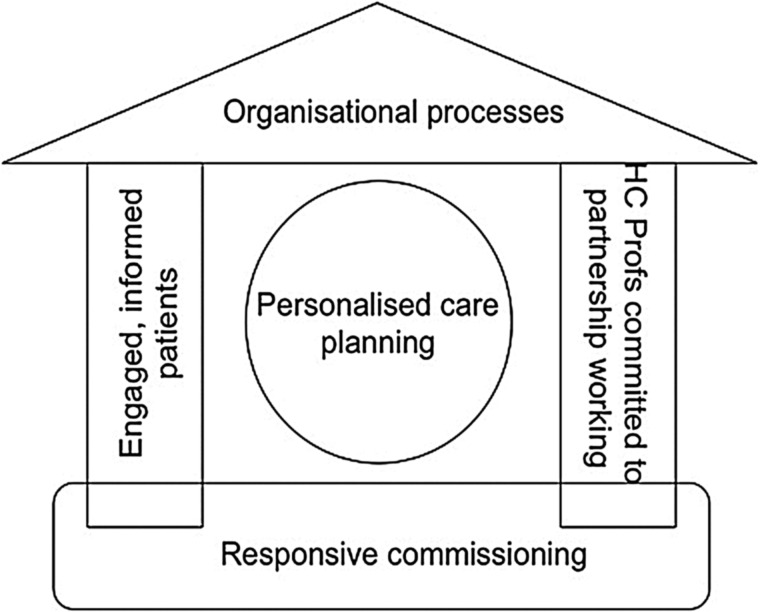

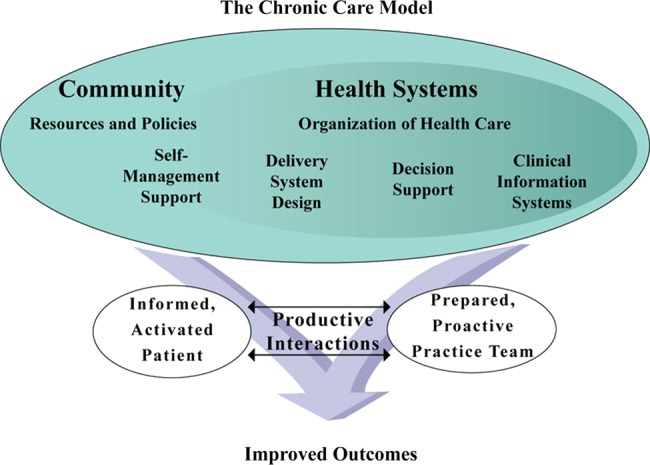

Within the context of this theoretical background, we offer a conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction. Two well-known conceptual models shape our own thinking. Coulter and colleagues45 have diagrammed a House of Care to describe an approach to the collaborative management of chronic health conditions. At the core of this House of Care is personalised care planning, which is supported by responsive policy and governance, organisational processes and workflows and the capacities, dispositions and behaviours of individual health professionals and patients. Wagner46 proposed a model for the delivery of chronic care, which invites attention to the importance of activated patients working with prepared professionals to create functional and clinical outcomes. The model also explicitly recognises the important support of both community and health system resources.

Figure 1.

House of Care. Reproduced with permission of The King's Fund. Source: Coulter A, Roberts S, Dixon A (2013). Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions: building the house of care. London: The King's Fund. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/delivering-better-services-people-long-term-conditions

Figure 2.

Chronic Care Model, developed by The MacColl Institute, © ACP-ASIM Journals and Books, reprinted with permission from ACP-ASIM Journals and Books. First published in: Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:2–4.

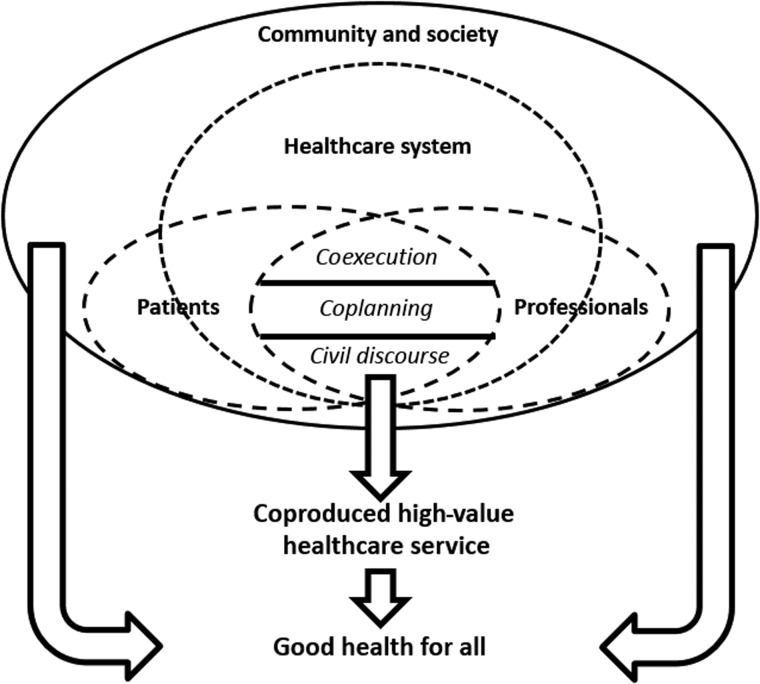

Building explicitly on these models, we propose a model for coproduced healthcare service in which patients and professionals interact as participants within a healthcare system in society.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction.

The concentric circles around the interactions between patients and professionals suggest that these partnerships are supported and constrained by the structure and function of the healthcare system and by the large-scale social forces and other social services at work in the wider community. As participants within the healthcare system and the community, the public (noted in the diagram as patients) and healthcare professionals also have agency to shape the system. Patients and professionals are not contained within the healthcare system, suggesting the myriad ways in which people may interact with individuals and organisations outside of the healthcare system to affect both health and healthcare service outcomes. The arrows illustrate that coproduced healthcare service contributes to the broader aim of good health for all, which is a consequence of many social forces and sources of caring.

We use the plural form of both ‘patients’ and ‘professionals’ to signal the importance of relationships within and between groups of patients and professionals. The dashed lines suggest that this coproductive lens blurs roles for patients and professionals and blurs the boundaries of the healthcare system within the larger community. Within the space of interaction between patients and professionals, the model explicitly recognises different levels of cocreative relationship. At the most basic level, good service coproduction requires civil discourse with respectful interaction and effective communication. Shared planning invites a deeper understanding of one another's expertise and values. Shared execution demands deeper trust, more cultivation of shared goals and more mutuality in responsibility and accountability for performance. Each level of shared work requires specific subject matter knowledge, know-how, dispositions and behaviours.

Understanding coproduction through examplar healthcare service innovations

Three cases drawn from the authors’ own personal experiences—a National Health Service (NHS) campaign, a clinic's experience with shared medical appointments and a facilitated network of patients with chronic disease—illustrate key features of the model's implications and limitations. Our central tenet is that healthcare services are always coproduced by patients and professionals in systems that support and constrain effective partnership. We do not improve healthcare services by adding coproduction. Rather, as we come to recognise this essential coproductive character of healthcare services, we see new opportunities for innovation and improvement.

NHS self-care

Our first case example is an educational initiative intended to help patients and health professionals develop the necessary competencies and dispositions for effective partnership. The Health Foundation's Co-Creating Health Initiative promoted self-management in the NHS.47 Patients and professionals in England and Scotland were trained to facilitate patient self-management of chronic pain, diabetes, depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The programme sought to move healthcare services from ‘relieving’ patients’ problems to ‘enabling’ patients to address their own concerns. Building on Lorig et al,41 the health professional who does to and for patients becomes a coach collaborating with patients, as they find their own best way to wellbeing. Clinical conversations shift from an illness model focused on patient problems to an asset model focused on patient strengths.

More than 600 patients and 900 professionals participated at one Scottish site in two workshops, Moving on Together for patients and Working in Partnership for professionals. Both workshops were codelivered by a patient and a health professional. The curriculum included communication skills, strategies for negotiating visit agendas and for articulating goals and monitoring progress, collaborative problem solving and action planning. An e-learning module complemented the clinician workshop.48

Participant reflections illustrate training-inspired changes:

Before…I thought it was more of me, imposing my ideas on the patient, but [after the training], it's more allowing the patient[s] to tell me what they want or what they expect, what they are hoping to achieve, if they are concerned with a problem… [Now it is] how can I support them or help them. It changed the way I approach consultations. (Nurse)48

Some participants have a very negative approach to professionals. Some feelings are based on bad experiences and [some are] linked to being unwell. Many are wary of professionals, but when lay tutors and clinicians can be seen working together, they can see this is something different—and [that] they also can have a different relationship with their own health professional (Lay tutor as cited in ref. 47)

Shared medical appointments

Our second case example illustrates a healthcare system design innovation that has the potential to support effective partnership between patients and health professionals. Shared medical appointments (‘group visits’) have been employed to expand access, decrease utilisation, improve outcomes, increase patient satisfaction and grow patient capacity for self-care.50–52 Designs vary, but group visits typically engage 8–15 patients for 90–120 min in a group educational session and a brief, billed individual provider visit. At a Cambridge Health Alliance affiliated clinic in Massachusetts, three groups of patients with diabetes (averaging about 10 patients per group) were convened. Groups met for 2 h monthly with an interprofessional healthcare team. The appointment included a meal (supported by an external grant), one-on-one clinical encounters with a medical resident and a group session with learning and conversation. Trainees and patients were invited as design partners; regular participant feedback and evaluation led to ongoing improvement.

In traditional 15-min individual clinic visits, providers often dominate visit agenda-setting. Increased use of guidelines and standardised measurement of performance often narrow the visit's focus and make it even more difficult for clinicians to respond to patient priorities. In group visits, however, a 10-member patient community shifts the power dynamic and actively shapes visit agenda-setting. The conversation often opens new territory. People share feelings that relate to their illness and complicate their ability to care for themselves. One clinician reflected:

The group has shown…diabetes from a patient perspective. As providers, we see…lab values, dietary plans, medication regimens, etc. [as] commonplace and… don't think twice about them. For patients, some of these things carry an enormous stigma…Hearing their perspective and fears has made me more aware. (Medical Resident)

Through group conversation, the paradigm shifts from the narrower (more deficit-focused) aim of meeting patient needs to the broader (more asset-focused) aim of working to achieve patient goals. In groups, people cocreate strategies to meet their needs with their peers and their professional team. Professional clinical expertise matters, but is repositioned:

The shared experience of illness is powerful. Advice from another patient carries a greater weight than advice from a professional, because patients can speak directly from their own experience. (Physician)

[The group visit] is an empowering setting where patients are mentors and students. [Patients] have the support to try new things (diet or medications) and realize that they are not alone. It's not an appointment—it's a dinner party patients look forward to! (Physician)

It opens your mind,…because you're starting to hear [others’] stories… We heal each other, we're healthy for each other. (Patient participant)

Cocreating health in a learning network

Our third case example illustrates a more disruptive healthcare system innovation in which patients and health professionals engage more fully as coproductive partners in healthcare service and create new structures for shared activity that reach beyond the boundaries of the clinic. ImproveCareNow is a network of patients, families, clinicians, and researchers for improving the health, care, service and costs experienced by children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The 71-site network serves more than one-third of US children and adolescents with IBD and has increased the clinical remission rate for patients from 60% to 79%. With the Collaborative Chronic Care Network, ImproveCareNow has developed the social, scientific, and technological infrastructure to alter how patients, parents, clinicians and researchers engage the healthcare system. A formal design process identified changes that shifted a hierarchical, provider-driven network to one in which all stakeholders work as partners in improving individual health, clinic healthcare service and network operations.

Three core elements enable this coproduced learning network: (1) clear and consistently articulated shared purpose (to improve disease remission rates) and values (to promote all network members as equal partners), (2) readily available resources to make participation easier for all and (3) processes and technology to support collaboration and knowledge sharing. Participating centres share outcome data transparently; the network showcases healthcare centre and stakeholder successes and provides a variety of technologies and venues for sharing personal narratives. Patients, families and professionals have worked together to develop tools that enable coexecution of good healthcare service: electronic previsit planning templates and population management algorithms; self-management support handbooks and shared decision-making tools; parent disease management binders; adolescent transition materials; handbooks for newly diagnosed families and a mobile app to track symptoms, plan a visit or test ideas about how to improve symptoms. Organised, representative leadership of patients, families and multidisciplinary healthcare professionals govern the network.

Resource and information cocreation strengthens the model. Patients, parents and research teams routinely collaborate. As a young adult patient and former chair of the ImproveCareNow Patient Advisory Council describes:

We are doing research…in a way that allows patients to actually participate not just in the data collection, but in [determining] the questions that are asked of the data, and even producing the results.

Parents and providers plan and coteach modules at network-wide learning sessions. The following email exchange between a network physician and parent while planning a plenary address illustrates the fundamental shift towards shared work.

Physician: What do you guys [parents] want me to do here? Or should I wait to comment when you guys [parents] all have a chance to solidify your take home message? Please tell me how to be helpful to you.

Parent: I’m struck by how fantastic it is that you even asked the question and framed it like you did! Serious kudos! This has to be a perfect example to the network of coproduction between physicians and parents.

A network quality improvement coach reflects on the shared value-creating system:

I used to believe…[patients and families] were partners, but also customers and [ImproveCareNow staff] had to make it all work well for them. I now realize it's all about working with them so they can help us get things right.

Today these patient and parent partners email me just as any of my other coworkers. They do so despite having busy full-time jobs inside or outside of their homes and despite the extra time they already devote to caring for children with a chronic illness. They share their ideas, ask for my input, worry about pushing us too fast, … worry about not pushing us fast enough, and ask how my kids are doing. Most of all, they are helping us walk together into a new model for running this Network, understanding we won't get it right every time, caring about the impact on others who are new to this level of partnership too, and above all, making sure we all stay connected to what this work is really about.

As a culture of cocreation and generosity grows, productive relationships form more naturally, and individuals—clinicians, parents and patients alike—seem to gain energy to do even more meaningful work together.

Coproducing good healthcare service: challenges and limitations

The same three cases illustrate limits and challenges to the application of this framework.

Diversity among patients

Not all patients have the desire or capacity to be active participants in coproducing their healthcare service. Sometimes patients are sick, and need a health professional to relieve a burden rather than enable self-care. In the emergency department, the operating room and the intensive care unit, professionals and patients necessarily employ Normann's relieving logic in greater measure. The character of the partnership between professionals and patients is dynamic and degrees of agency shift across time and setting and circumstance. People from every background and social location become patients with widely disparate coproduction dispositions and capacities.

At the Scottish site described above, not all patients elect to participate in training. Even after completing training, patients are differently willing and able to embrace a more active partnership with their clinicians. Patients who accept the invitation to engage in group visits and prioritise ongoing attendance are a small subset of the Cambridge clinic's patient population. Many ImproveCareNow participants remain unaware of how the Network drives improvements in their own care and do not recognise (or take) the opportunity to become involved. Clinicians and care teams do not always recognise families ready to take a more active role. Scheduling meetings and right-sizing commitments of time and energy for patients and families remain challenging.

Power and responsibility

While many might welcome the opportunity to engage as interlocutors with their healthcare service professionals at the level of civil discourse, the idea of mutual accountability for outcomes is controversial.43 It is neither possible nor desirable to share power and responsibility equitably between patients and professionals in all situations. The burden of responsibility for medical and surgical error, for example, must fall disproportionately on healthcare professionals. When patients make unhealthy choices, health professionals must continue to engage and the healthcare service system must continue to function as a safety net. The healthcare system cannot abandon patients who do not have the resources or expertise to partner effectively in coproducing good health outcomes for themselves.

Letting the pendulum swing too far

The model may appear to diminish the value of professional expertise by transferring care responsibility to patients and families. Sorting helpful from available information is complex; requiring too much patient autonomy can result in bad health outcomes.53 Clinician partners in the ImproveCareNow network sometimes articulate this fear. As professionals share agenda setting in interactive group visits in the Cambridge clinic, the conversations sometimes seem (to health professionals) to be steering ‘off course’. Shared navigation is not always easy.

Contextualising standardisation

Coproducing healthcare service challenges standardisation. Reducing unnecessary, unintended variation in healthcare service has improved quality and safety in many meaningful ways. The coproduction lens invites increasing attention to necessary adaptation and asks healthcare professionals to let patient and family priorities dominate in driving ‘intended’ variation in healthcare service. Easing the isolation of living with diabetes may be more important this year to one group participant's wellbeing than completing a timely eye examination. Publicly reported performance on quality metrics may not immediately reflect group visit work. Shared values and alignment of patients and professionals allow all ImproveCareNow network members to join in the shared aim of increasing IBD remission rates, even as individuals pursue different paths towards the goal. Noticing the cocreative dynamics of healthcare service invites a pause in what sometimes seems an inexorable march towards standardisation of healthcare professional work. Greater discernment between necessary and unnecessary variation will be key.

A resistant healthcare culture

Engaging professionals and patients as coproductive partners is difficult and time consuming. Years after introducing the construct of shared decision making, principles are rarely employed in patient–clinician encounters.54 Even after training, many patients and professionals in Scotland inconsistently apply new-found skills and orientation. Conversations revert easily to professional-centric priorities and professionals slip into providing healthcare service as a product—a quantum of advice, a package of evaluation and management. When productivity pressures increase, professionals migrate towards ‘what's-the-matter-with-you medicine’ and away from ‘what-matters-to-you medicine.’55 It is difficult for the NHS to calculate the long-term return on investment in evaluating these paradigm-shifting trainings.

Implications, next steps and questions for change agents

In our efforts to improve healthcare service, we have often inadvertently approached the work as though healthcare was a ‘good’ produced by healthcare professionals. Recognising that healthcare service is a ‘service’ coproduced by patients and health professionals invites four clusters of opportunity for action.

-

Education of professionals and the public

Cocreating healthcare service well requires new skills, new knowledge and new dispositions for health professionals and for patients. The NHS-sponsored workshops highlight one model for learning. What other models for health professional formation and public education will be effective in recalibrating expectations and developing and sustaining new habits?

-

Healthcare system redesign

The design of the healthcare delivery system—at the level of the clinical microsystem and beyond—has the power to help or hinder effective coproductive relationships. Shared medical appointments highlight one delivery system innovation. In what other ways might the healthcare delivery system evolve to facilitate cocreative relationships between patients and healthcare professionals? How might efforts to invite better partnership between patients and professionals harness the energy of new information technologies? What will encourage effective codesign? How will newly designed systems be held accountable? What changes will be necessary in healthcare regulation and finance to support these models?

-

Redesign outside and at the edges of the healthcare system

Current healthcare service system boundaries are limited by a professional-knows-best mindset, which can be blind to the powerful actions and forces that shape health outside of the boundaries of the healthcare system. Transcending those limits unleashes new resources, as evidenced by ImproveCareNow. Other disruptive models will emerge. What new partnerships will emerge? Will coproduction help decrease total medical expense? How will cost savings be distributed? What values will drive these new systems of service?56 How will the hazards of new options be recognised, prevented?

-

Measurement of good healthcare service

Though the science of patient-centred outcomes is growing, health professionals and payers have historically defined their own metrics for success.57–62 Evidence-based guidelines have sometimes been applied as product specifications and adherence to these specifications has been measured to reward and punish healthcare professionals as producers. Measures that accurately reflect coproduced service and its results will need to supplant product paradigm metrics. Which measures will help us understand coproductive processes? What outcome measures will accurately reflect the diversity of ‘what matters to you’ when you are the patient? How will we know that change is an improvement?

Conclusion

Healthcare is not a product manufactured by the healthcare system, but rather a service, which is cocreated by healthcare professionals in relationship with one another and with people seeking help to restore or maintain health for themselves and their families. This coproductive partnership is facilitated or hindered by many forces operating at the level of the healthcare system and the wider community. This frame has implications for understanding the aim of healthcare service and the potential roles and responsibilities of all participants. Improving healthcare service using this construct invites us to consider new ways of preparing health professionals and socialising patients, new organisational forms and structures for healthcare service delivery, and new metrics for measuring success. Like any paradigm, the construct of coproduced healthcare service is imperfect and contains its own pragmatic challenges and moral hazards, but these limitations do not negate its utility. Marcel Proust suggested that the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.63 Perhaps this lens of coproduction will help us see healthcare service with new eyes.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Peter Margolis at @PeterAMargolis

Contributors: The seven-member writing group convened approximately 12 times to develop the intellectual content of the article. The group responded collectively to several written drafts of the paper and radically revised the substance of the article through conversation. The intellectual genesis of the article was provided by PB, who convened the writing group. Most of the text of the article was written principally by MB, who is identified as the first author. MS, PM and LO-A are leaders in the Cincinnati Children's Hospital and Medical Center-based ImproveCareNow network and prepared the text that describes their experience with that initiative. Hans Hartung has been an active participant in the Health Foundation's Co-Creating Health Initiative and prepared the text that describes his experience with that initiative. GA was an integral member of the writing group who provided a critical nursing perspective on the construct of health coproduction.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (NIH NIDDK R01DK085719), Health Foundation, Arnold P Gold Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This is not an empirical study, but rather a conceptual paper of grounded theory that engages three case studies as exemplars. Additional data regarding the Co-Creating Health Initiative sponsored by the Health Foundation is available from the Health Foundation. Additional data regarding the ImproveCareNow network is available through Cincinnati Children's Hospital and Medical Center.

References

- 1.Hippocrates. The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. Trans. Francis Adams Vol 2 London, UK: Sydenham Society, 1849:697. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. . Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies E, Shaller D, Edgman-Levitan S, et al. . Evaluating the use of a modified CAHPS survey to support improvements in patient-centered care: lessons from a quality improvement collaborative. Health Expect 2007;11:160–76. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00483.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCannon J, Berwick DM. A new frontier in patient safety. JAMA 2011;305:2221–2. 10.1001/jama.2011.742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs V. The service economy. New York, NY: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bovaird T. Beyond engagement and participation: user and community coproduction of public services. Public Adm Rev 2007;67:846–60. 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks RB, Baker PC, Kiser L, et al. . Consumers as coproducers of public services: some economic and institutional considerations. Policy Stud J 1981;9:1001–11. 10.1111/j.1541-0072.1981.tb01208.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garn HA, Flax MJ, Springer M, et al. . Models for indicator development: a framework for policy analysis. Washington DC: Urban Institute, 1976:1206–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alford J. The multiple facets of co-production: building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Pub Manag Rev 2014;16:299–316. 10.1080/14719037.2013.806578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostrom E. Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev 1996;24:1073–87. 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toffler A. The third wave: the classic study of tomorrow. New York, NY: Bantam, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Normann R. Reframing business: when the map changes the landscape. Chichester, UK: Wiley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pente E, Ward P, Brown M, et al. . The co-production of historical knowledge: implications for the history of identities. Identity pap J Br Ir Stud 2015;1:32–53. 10.5920/idp.2015.1132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuurnas S, Stenvall J, Rannisto P-H. The impact of co-production on frontline accountability: the case of the conciliation service. Int Rev Adm Sci 2015. [epub ahead of print Jul 2015]. doi:0020852314566010 10.1177/0020852314566010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. . SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669–86. 10.1080/00140139.2013.838643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radnor Z, Osborne SP, Kinder T, et al. . Operationalizing co-production in public services delivery the contribution of service blueprinting. Pub Manag Rev 2014;16:402–23. 10.1080/14719037.2013.848923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alford J, Yates S. Co-production of public services in Australia: the roles of government organisations and co-producers. Aust J Pub Adm 2015:1–17. 10.1111/1467-8500.12157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pestoff V. Towards a paradigm of democratic participation: citizen participation and co-production of personal social services in Sweden. Ann Pub Cooperative Econ 2009;80:197–224. 10.1111/j.1467-8292.2009.00384.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armitage D, Berkes F, Dale A, et al. . Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada's Arctic. Global Environ Change 2011;21:995–1004. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandström P. A toolbox for co-production of knowledge and improved land use dialogues: the perspective of reindeer husbandry [PhD Thesis]. Umeå, Sweden: Department of Forest Resource Management, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 2015:20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flood S. Enhancing adaptive capacity through co-production of knowledge in New Zealand. Proceedings of the Resilient Cities 2014 congress; 5th Global Forum on Urban Resilience and Adaptation; Bonn, Germany, 29–31 May, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osborne SP, Radnor Z, Kinder T, et al. . The SERVICE Framework: a public-service-dominant approach to sustainable public services. Br J Manag 2015;26:424–38. 10.1111/1467-8551.12094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bovaird T, Stoker G, Jones T, et al. . Activating collective co-production of public services: influencing citizens to participate in complex governance mechanisms in the UK. Int Rev Adm Sci 2015. [epub ahead of print 5 Jun 2015]. doi:0020852314566009 10.1177/0020852314566009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pestoff V, Osborne SP, Brandsen T. Patterns of co-production in public services: some concluding thoughts. Pub Manag Rev 2006;8:591–5. 10.1080/14719030601022999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alford J. Engaging public sector clients: from service-delivery to co-production. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grönroos C. In search of a new logic for marketing: foundations of contemporary theory. West Sussex, UK: Wiley, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargo SL, Lusch RF. From goods to service(s): Divergences and convergences of logics. Ind Mark Manag 2008;37:254–9. 10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osborne SP, Radnor Z, Nasi G. A new theory for public service management? Toward a (public) service-dominant approach. Am Rev Pub Adm 2012;43:135–58. 10.1177/0275074012466935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loeffler E, Power G, Bovaird T, Hine-Hughes F, eds. Co-production of health and wellbeing in Scotland. Birmingham, UK: Governance International, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunston R, Lee A, Boud D, et al. . Co-production and health system reform—from re-imagining to re-making. Aust J Pub Adm 2009;68:39–52. 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2008.00608.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iedema R, Sorensen R, Jorm C, et al. . Co-producing care. In: Sorensen R, Iedema R, eds. Managing clinical processes in health services. Sydney: Mosby, 2008:105–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabadosa KA, Batalden PB. The interdependent roles of patients, families and professionals in cystic fibrosis: a system for the coproduction of healthcare and its improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:i90–4. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amery J. Co-creating in health practice. London, UK: Radcliffe, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butler C, Greenhalgh T. What is already known about involving users in service transformation. In: Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Woodard F, eds. User involvement in health care. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011: chapter 2:10–27. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braddock CH. The emerging importance and relevance of shared decision making to clinical practice. Med Decis Making 2010;30(Suppl 1):5S–7S. 10.1177/0272989X10381344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carman K, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. . Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. . Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach MC, Inui T. the Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. Relationship-centered care: a constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(Suppl 1): S3–8. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bate P, Robert G. Bringing user experience to health care improvement: the concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. . Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care 1999;37:5–14. 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, et al. . A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS—Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 2.53.), 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ewert B, Evers A. An Ambiguous concept: on the meanings of co-production for health care users and user organizations? Voluntas 2014;25:425–42. 10.1007/s11266-012-9345-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vennik FD, van de Bovenkamp HM, Putters K, et al. . Co-production in healthcare: rhetoric and practice. Int Rev Adm Sci 2015. [epub ahead of print 29 Jun 2015]. doi:0020852315570553 10.1177/0020852315570553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coulter A, Roberts S, Dixon A. Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions: building the house of care. London, UK: Kings Fund, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newbronner L, Chamberlain L, Borthwick R, et al. . Sustaining and spreading self-management support. Lessons from co-creating health phase 2. London, UK: Health Foundation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.http://personcentredcare.health.org.uk/resources/development-of-e-learning-module-clinicians/ (accessed 11 Dec 2014).

- 49.Wallace LM, Turner A, Kosmala-Anderson J, et al. . Co-creating Health: evaluation of first phase. London, UK: Health Foundation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Housden L, Wong S, Dawes M. Effectiveness of group medical visits for improving diabetes care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2013;185:E635–44. 10.1503/cmaj.130053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trento M, Passera P, Borgo E, et al. . A 5 year randomized controlled study of learning, problem solving ability and quality of life modifications in people with type 2 diabetes managed by group care. Diab Care 2004;27:670–5. 10.2337/diacare.27.3.670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edelman D, McDuffie J, Oddone E, et al. . Shared medical appointments for chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Evidence-based synthesis program. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, et al. . A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:673–83. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Epstein R, Alper B, Quill T. Communicating evidence for participatory decision making. JAMA 2004;291:2359–66. 10.1001/jama.291.19.2359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 2012;366:780–1. 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidoff F. Systems of service: reflections on the moral foundations of improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20(Suppl 1):i5ei10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R. The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med 2005;60:833–43. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marshall S, Haywood K, Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract 2006;12:559–68. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00650.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, et al. . Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BMJ 2015;350:g7818 10.1136/bmj.g7818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. . Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Eng J Med 2007;356:486–96. 10.1056/NEJMsa064964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, et al. . Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med 2009;361:368–78. 10.1056/NEJMsa0807651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jha AK, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, et al. . The long-term effect of premier pay for performance on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1606–15. 10.1056/NEJMsa1112351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marcel Proust. BrainyQuote.com, Xplore Inc, 2015. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/m/marcelprou107111.html (accessed 26 Jul 2015).