Abstract

Objectives

To quantify age, sex, sport and training type-specific effects of resistance training on physical performance, and to characterise dose–response relationships of resistance training parameters that could maximise gains in physical performance in youth athletes.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies.

Data sources

Studies were identified by systematic literature search in the databases PubMed and Web of Science (1985–2015). Weighted mean standardised mean differences (SMDwm) were calculated using random-effects models.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Only studies with an active control group were included if these investigated the effects of resistance training in youth athletes (6–18 years) and tested at least one physical performance measure.

Results

43 studies met the inclusion criteria. Our analyses revealed moderate effects of resistance training on muscle strength and vertical jump performance (SMDwm 0.8–1.09), and small effects on linear sprint, agility and sport-specific performance (SMDwm 0.58–0.75). Effects were moderated by sex and resistance training type. Independently computed dose–response relationships for resistance training parameters revealed that a training period of >23 weeks, 5 sets/exercise, 6–8 repetitions/set, a training intensity of 80–89% of 1 repetition maximum (RM), and 3–4 min rest between sets were most effective to improve muscle strength (SMDwm 2.09–3.40).

Summary/conclusions

Resistance training is an effective method to enhance muscle strength and jump performance in youth athletes, moderated by sex and resistance training type. Dose–response relationships for key training parameters indicate that youth coaches should primarily implement resistance training programmes with fewer repetitions and higher intensities to improve physical performance measures of youth athletes.

Keywords: Strength, Weight lifting, Children, Adolescent, Physical fitness

Introduction

Resistance training (RT) is a safe and effective way to improve proxies of physical performance in healthy children and adolescents when appropriately prescribed and supervised.1–4 Several meta-analyses have shown that RT has the potential to improve muscle strength and motor skills (eg, jump performance) in children and adolescents.1 5–7 However, youth athletes have different training capacities, adherence, physical demands of activities, physical conditions and injury risks compared with their non-athlete peers; so the generalisability of previous research on youth athletes is uncertain.8–10

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one meta-analysis available that examined the effects of RT on one specific proxy of physical performance (ie, jump performance) and in one age group (ie, youth aged 13–18 years).11 It is reasonable to hypothesise that factors such as age, sex and sport may influence the effects of RT. Therefore, a systematic review with meta-analysis is needed to aggregate findings from the literature in terms of age, sex and sport-specific effects of RT on additional physical performance measures (eg, muscle strength, linear sprint performance, agility, sport-specific performance) in youth athletes.

There is also little evidence-based information available regarding how to appropriately prescribe exercise to optimise training effects and avoid overprescription or underprescription of RT in youth athletes.12 The available guidelines for RT prescription are primarily based on expert opinion, and usually transfer study findings from the general population (ie, healthy untrained children and adolescents) to youth athletes. This is important because the optimal dose to elicit a desired effect is likely to be different for trained and untrained youth.13

Therefore, the objectives of this systematic literature review and meta-analysis were (1) to analyse the effectiveness of RT on proxies of physical performance in youth athletes by considering potential moderator variables, including age, sex, sport and the type of RT, and (2) to characterise dose–response relationships of RT parameters (eg, training period, training frequency) by quantitative analyses of intervention studies in youth athletes. We hypothesised that (1) RT would have a positive effect on proxies of physical performance in youth athletes, and (2) the effects would be moderated by age, sex, sport and RT type.

Methods

Our meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).14

Literature search

We performed a computerised systematic literature search in the databases PubMed and Web of Science.

The following Boolean search syntax was used: (‘strength training’ OR ‘resistance training’ OR ‘weight training’ OR ‘power training’ OR ‘plyometric training’ OR ‘complex training’ OR ‘weight-bearing exercise’) AND (athlete OR elite OR trained OR sport) AND (children OR adolescent OR youth OR puberty OR kids OR teens OR girls OR boys). The search was limited to: full-text availability, publication dates: 01/01/1975 to 07/31/2015, ages: 6–13; 13–18 years, and languages: English, German. The reference list of each included study and relevant review article1 4–6 11 15–19 was screened for title to identify any additional suitable studies for inclusion in our review.

Selection criteria

Based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (table 1), two independent reviewers (ML and OP) screened potentially relevant articles by analysing titles, abstracts and full texts of the respective articles to elucidate their eligibility. In case ML and OP did not reach an agreement concerning inclusion of an article, UG was contacted.

Table 1.

Selection criteria

| Category | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Healthy young athletes (mean age of 6–18 years) | Children/adolescents without an athletic background (ie, organised athletic training) |

| Intervention | Resistance training (RT; specific conditioning method, which involves the use of a wide range of resistive loads and a variety of training types designed to enhance proxies of health, fitness and sports performance) | Fewer than 6 RT sessions |

| Comparator | Active control (ie, age-matched; conducting the same regular training as the intervention group) in order to avoid bias due to growth and maturation-related performance enhancements16 | Only a passive control (ie, no regular training) and/or an alternative training group as control only (eg, stable vs unstable RT) |

| Outcome | At least one measure of muscle strength, vertical jump performance, linear sprint performance, agility and/or sport-specific performance | Effects of nutritional supplements; report no means and SDs/SE for the intervention and control groups post test in the results and did not reply to our inquiries sent by email |

| Study design | Controlled study | No controlled study |

Coding of studies

Each study was coded for certain variables listed in table 2. Our analyses focused on different outcome categories. If studies reported multiple variables within one of these outcome categories, only one representative outcome variable was included in the analyses. The variable with the highest priority for each outcome is mentioned in table 2.

Table 2.

Study coding

| Sex |

|

| Chronological age |

|

| Biological age |

|

| Sport |

|

| Type of resistance training |

|

| Outcome categories |

|

If a study solely used other tests, we included those tests in our quantitative analyses that were most similar with regard to the ones described above in terms of their temporal/ spatial structure.

Further, we coded RT according to the following training parameters: training period, training frequency, and training volume (ie, number of sets per exercise, number of repetitions per set), training intensity, temporal distribution of muscle action modes per repetition, and rest (ie, rest between sets and repetitions). Training parameters were categorised according to common classifications of RT protocols.21 If a study reported exercise progression over the training period, the mean number of sets per exercise, repetitions per sets, rest between sets and training intensity were computed.

To obtain sufficient statistical power to calculate dose–response relationships, we summarised RT types as conventional RT (ie, machine based, free weights, combined machine based and free weights, functional training) and plyometric training (ie, jumping). As it is not possible to classify complex training as either conventional RT nor plyometric training,22 we excluded these studies23–27 from dose–response analyses. Our dose–response analyses were computed independent of age, sex and sport.

Assessment of risk of bias

The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale was used to quantify the risk of bias in eligible studies and to provide information on the general methodological quality of studies. The PEDro scale rates internal study validity and the presence of statistical replicable information on a scale from 0 (high risk of bias) to 10 (low risk of bias) with ≥6 representing a cut-off score for studies with low risk of bias.28

Statistical analyses

To determine the effectiveness of RT on proxies of physical performance and to establish dose–response relationships of RT in youth athletes, we computed between-subject standardised mean differences (SMD=(mean postvalue intervention group−mean postvalue control group)/pooled standard deviation). We adjusted the SMD for the respective sample size by using the term (1−(3/(4N-9))).29 Our meta-analysis on categoric variables was computed using Review Manager V.5.3.4 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008). Included studies were weighted according to the magnitude of the respective SE using a random-effects model.

At least two RT intervention groups had to be included to calculate weighted mean SMDs, hereafter refered to as SMDwm, for each performance category.30 We used Review Manager for subgroup analyses: computing a weight for each subgroup, aggregating SMDwm values of specific subgroups, comparing subgroup effect sizes with respect to differences in intervention effects across subgroups.31 To improve readability, we reported positive SMDs if superiority of RT compared with active control was found. Heterogeneity was assessed using I² and χ2 statistics.

Owing to a low number of studies in each physical performance outcome category that completely reported information on the applied RT parameters, metaregression was precluded.30 According to a scale for determining the magnitude of effect sizes in strength training research for individuals who have been consistently training for 1–5 years,32 we interpreted SMDwm as: trivial (<0.35); small (0.35–0.79); moderate (0.80–1.50); large (≥1.50). The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Study characteristics

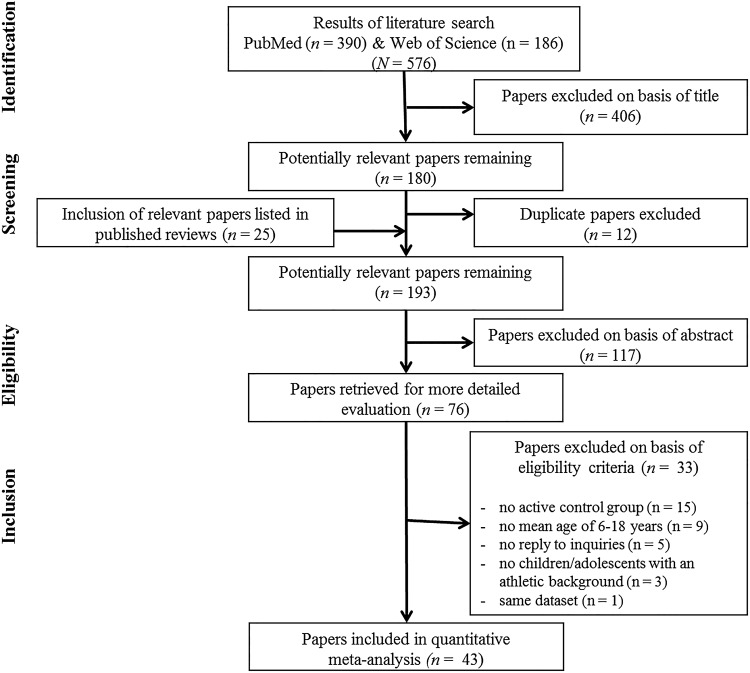

A total of 576 potentially relevant studies were identified in the electronic database search (figure 1). Finally, 43 studies remained for the quantitative analyses. A total of 1558 youth athletes participated, and of these, 891 received RT in 62 RT intervention groups. The sample size of the RT intervention groups ranged from 5 to 54 participants (table 3).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the different phases of the search and study selection.

Table 3.

Included studies examining the effects of resistance training in youth athletes

| Author, year | N Exp | N Con | Biological age | Chronological age | Sex | Sport | RT exercise | TP | TF | TI | Sets | Reps | Rest | PEDro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alves 201027* | EG I: 9 EG II: 8 |

6 | NA | 17.4±0.6 | M | Soccer | EG I (1/week): CT (eg, squats and skippings; leg extension and jumps) | 6 | 1 | 85 | 1 | 6 | NA | 4 |

| EG II (2/week): CT (eg, squats and skippings; leg extension and jumps) | 6 | 2 | 85 | 1 | 6 | NA | ||||||||

| Athanasiou 200433 | 10 | 10 | NA | 13–15 | M | Basketball | MB and FW (eg, incline press, leg extension, leg curl) | 8 | 2 | NA | 3 | 14 | NA | 2 |

| Behringer 201334 | EG I: 13 EG II: 10 |

10 | (post-) pubertal | EG I: 15.1±1.8; EG II: 15.5±0.9; CG: 14.6±1.8 | M | Tennis | EG I: MB (eg, low pulley, dead lift, leg press, lateral pull down) | 8 | 2 | 75 | 2 | 15 | 60 | 5 |

| EG II: PT (lower and upper body: eg, skipping, lateral barrier hop, push-ups) | 8 | 2 | NA | 4 | 13 | 20 | ||||||||

| Bishop 200935 | 11 | 11 | NA | EG: 13.1±1.4; CG: 12.6±1.9 | ND | Swimming | PT (lower body: eg, hurdle jumps, DJ, jump to box) | 8 | 2 | NA | 3 | 5 | 60–90 | 6 |

| Brown 198636 | 13 | 13 | NA | 15.0±0.7 | M | Basketball | PT (lower body: DJ (dropping height: 45 cm) | 12 | 3 | NA | 3 | 10 | 30–45 | 4 |

| Cavaco 201423* | EG I: 5 EG II: 5 |

6 | NA | EG I: 13.8±0.5 EG II: 14.2±0.5 CG: 14.2±0.8 |

M | Soccer | EG I (1/ week): CT (eg, squats and linear/non-linear sprints) | 6 | 1 | 85 | 3 | 6 | 180 | 5 |

| EG II (2/week): CT (eg, squats and linear/non-linear sprints) | 6 | 2 | 85 | 3 | 6 | 180 | ||||||||

| Chelly 200937 | 11 | 11 | NA | EG: 17±0.3; CG: 17±0.5 | M | Soccer | FW (squats) | 8 | 2 | 80 | 4 | 4 | NA | 4 |

| Chelly 201438 | 12 | 11 | NA | 17.4±0.5 | M | Handball | PT (upper and lower body: eg, hurdle jumps, DJ, push-ups) | 8 | 2 | NA | 4 | 10 | NA | 6 |

| Chelly 201539 | 14 | 13 | Prepubertal | 11.9±1.0 | M | Track and field | PT (lower body: ie, hurdle jumps, DJ) | 10 | 3 | NA | 5 | 10 | NA | 5 |

| Christou 200640 | 9 | 9 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 13.8±0.4; CG:13.5±0.9 | M | Soccer | MB and FW (eg, leg press, bench press, leg extension, pec-dec) | 16 | 2 | 68 | 3 | 12 | 150 | 4 |

| DeRenne 199641 | EG I: 7 EG II: 8 |

6 | NA | 13.3±1.3 | M | Baseball | EG I (1/week): MB and FW (eg, bench press, leg extension, leg curl) | 12 | 1 | 88 | 1 | 10 | NA | 3 |

| EG II (2/week): MB and FW (eg, bench press, leg extension, leg curl) | 12 | 2 | 88 | 1 | 10 | NA | ||||||||

| Escamilla 201042 | 17 | 17 | NA | 12.9±1.7; CG: 12.5±1.5 | M | Baseball | FT (upper body; elastic tubes) | 4 | 2 | NA | 1 | 23 | NA | 4 |

| Fernandez-Fernandez 201343 | 15 | 15 | NA | EG: 13.2±1.6; CG: 13.2±0.5 | M | Tennis | FT (core training; own body weight) | 6 | 3 | NA | 2 | 17 | 58 | 5 |

| Ferrete 201424* | 11 | 13 | NA | EG: 9.3±0.3 CG: 8.3±0.3 |

M | Soccer | CT (eg, squats and CMJ) | 26 | 2 | NA | 3 | 7 | NA | 6 |

| Gorostiaga 199944 | 9 | 9 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 15.1±0.7; CG: 15.1±0.5 | M | Handball | MB (eg, leg press, leg curl, bench press) | 6 | 2 | 65 | 4 | 8 | 90 | 4 |

| Gorostiaga 200445 | 8 | 11 | NA | EG: 17.3±0.5; CG: 17.2±0.7 | M | Soccer | FW (eg, squats, power clean) and PT (eg, hurdle jumps, box jumps) | 11 | 2 | NA | 3 | 4 | 120 | 5 |

| Granacher 201146 | 14 | 14 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 16.7±0.6; CG: 16.8±0.7 | M and F | eg, soccer | MB (eg, squats, leg press, calf raise) | 8 | 2 | 35 | 5 | 10 | 150 | 6 |

| Hetzler 199747 | EG I: 10 EG II: 10 |

10 | (post-) pubertal | EG I: 13.2±0.9; EG II: 13.8±0.6; CG: 13.9±1.1 | M | Baseball | EG I (novice): MB and FW (eg, bench press, leg curl, leg press, biceps curls) | 12 | 3 | 56 | 3 | 10 | 180 | 4 |

| EG II (experienced): MB and FW (eg, bench press, leg press, biceps curls) | 12 | 3 | 56 | 3 | 10 | 180 | ||||||||

| Keiner 201448 | EG I: 14 EG II: 30 EG III: 18 |

CG I: 12 CG II: 21 CG III: 17 |

NA | EG and CG I: U17 EG and CG II: U15 EG and CG III: U13 |

NA | Soccer | EG I: FW (eg, squats, bench press) (U17) | 80 | 2 | 83 | 5 | 7 | 220 | 3 |

| EG II: FW (eg, squats, bench press) (U15) | 80 | 2 | 83 | 5 | 7 | 220 | ||||||||

| EG III: FW (eg, squats, bench press) (U13) | 80 | 2 | 83 | 5 | 7 | 220 | ||||||||

| Klusemann 201249 | EG I: 13 EG II: 11 |

12 | NA | M: 14±1; F: 15±1 | M and F | Basketball | EG I: FT (body weight RT; supervised) | 6 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 |

| EG II: FT (body weight RT; video-based) | 6 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Kotzamanidis 200550 | 11 | 11 | NA | EG: 17.1±1.1; CG: 17.8±0.3 | M | Soccer | NA (conventional RT) | 13 | 3 | 87 | 4 | NA | 180 | 3 |

| Martel 200551 | 10 | 9 | NA | 15±1 | F | Volleyball | PT (lower body: eg, power skips, single leg bounding; aquatic) | 6 | 2 | NA | 4 | NA | 30 | 5 |

| Matavulj 200152 | EG I: 11 EG II: 11 |

11 | NA | 15–16 | M | Basketball | EG I: PT (lower body: DJ; dropping height: 50 cm) | 6 | 3 | NA | 3 | 10 | 30 | 4 |

| EG II: PT (lower body: DJ; dropping height: 100 cm) | 6 | 3 | NA | 3 | 10 | 30 | ||||||||

| Meylan 200953 | 14 | 11 | NA | EG: 13.3±0.6; CG: 13.1±0.6 | M | Soccer | PT (lower body: eg, hurdle jumps, lateral bounding, skipping) | 8 | 2 | NA | 3 | 9 | 90 | 4 |

| Potdevin 201154 | 12 | 11 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 14.3±0.2; CG: 14.1±0.2 | M and F | Swimming | PT (lower body: eg, DJ, hurdle jumps) | 6 | 2 | NA | 3 | 10 | NA | 5 |

| Ramirez-Campillo 2014a55 | EG I: 10 EG II: 10 EG III: 10 |

10 | NA | EG I: 11.6±1.4; EG II: 11.4±1.9; EG III: 11.2±2.3; CG: 11.4±2.4 | M | Soccer | EG I: PT (lower body; vertical PT) EG II: PT (lower body; horizontal PT) EG III: PT (lower body; combined vertical and horizontal PT) |

6 | 2 | NA | 3 | 8 | 60 | 5 |

| 6 | 2 | NA | 3 | 8 | 60 | |||||||||

| 6 | 2 | NA | 2 | 8 | 60 | |||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo 2014b56 | EG I: 8 EG II: 8 |

8 | NA | 13.0±2.3 | M | Soccer | EG I: PT (lower body: vertical and horizontal jumps) | 6 | 2 | NA | 2 | 5 | 60 | 5 |

| EG II: PT (lower body: vertical and horizontal jumps; progressive PT) | 6 | 2 | NA | 2 | 8 | 60 | ||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo 2014c57 | 38 | 38 | (post-) pubertal | 13.2±1.8 | M | Soccer | PT (lower body: DJ) | 7 | NA | NA | 2 | 10 | 90 | 5 |

| Ramirez-Campillo 2014d58 | EG I: 13 EG II: 13 EG III: 11 |

14 | Prepubertal | 10.4±2.3 | M | Soccer | EG I: PT (lower body: DJ; 30 s interest rest) | 7 | 2 | NA | 2 | 10 | 30 | 5 |

| EGII: PT (lower body: DJ; 60 s interest rest) | 7 | 2 | NA | 2 | 10 | 60 | ||||||||

| EG III: PT (lower body: DJ; 90 s interest rest) | 7 | 2 | NA | 2 | 10 | 120 | ||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo 2015a59 | EG I: 54 EG II: 48 |

55 | (post-) pubertal | EG I: 14.2±2.2; EG II: 14.1±2.2; CG: 14.0±2.3 | M | Soccer | EG I: PT (lower body: vertical and horizontal jumps; 24 h recovery between sessions) | 6 | 2 | NA | 2 | 8 | 120 | 5 |

| EG II: PT (lower body: vertical and horizontal jumps; 48 h recovery between sessions) | 6 | 2 | NA | 2 | 8 | 120 | ||||||||

| Ramirez-Campillo 2015b60 | EG I: 12 EG II: 16 EG III: 12 |

14 | NA | 11.4±2.2 | M | Soccer | EG I: PT (lower body: bipedal jumps) | 6 | 2 | NA | 6 | 8 | NA | 5 |

| EG II: PT (lower body: monopedal jumps) | 6 | 2 | NA | 3 | 8 | NA | ||||||||

| EG III: PT (lower body: monopedal and bipedal jumps | 6 | 2 | NA | 2 | 8 | NA | ||||||||

| Rubley 201161 | 10 | 6 | NA | 13.4±0.5 | F | Soccer | PT (lower body: eg, hurdle jumps, DJ) | 14 | 1 | NA | 2 | 10 | NA | 4 |

| Saeterbakken 201162 | 14 | 10 | NA | EG: 16.6±0.3 | F | Handball | FT (sling-training) | 6 | 2 | 87 | 4 | 5 | 90 | 4 |

| Sander 201363 | EG I: 13 EG II: 30 EG III: 18 |

CG I: 15 CG II: 25 CG III: 33 |

NA | EG and CG I: U17 EG and CG II: U15 EG and CG III: U13 |

NA | Soccer | EG I: FW (eg, squats, bench press) (U17) | 80 | 2 | 83 | 5 | 7 | 220 | 2 |

| EG II: FW (eg, squats, bench press) (U15) | 80 | 2 | 83 | 5 | 7 | 220 | ||||||||

| EG III: FW (eg, squats, bench press) (U13) | 80 | 2 | 83 | 5 | 7 | 220 | ||||||||

| Santos 200826 | 15 | 10 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 14.7±0.5 CG: 14.2±0.4 |

M | Basketball | CT (eg, pull over, decline press, depth jump, cone hops) | 16 | 2 | 70 | 3 | 11 | 150 | 4 |

| Santos 201164 | 14 | 10 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 15.0±0.5; CG: 14.5±0.4 | M | Basketball | PT (lower and upper body: eg, hurdle jumps, box jumps) | 10 | 2 | NA | 3 | 10 | 120 | 5 |

| Santos 201265 | 15 | 10 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 14.5±0.6; CG: 14.2±0.4 | M | Basketball | MB (eg, leg press, lat pull down, leg extension, pullover) | 10 | 2 | 75 | 3 | 11 | NA | 3 |

| Siegler 200366† | 17 | 17 | NA | 16.5±0.9; CG: 16.3±1.4 | F | Soccer | FW (eg, squat, leg extensions, calf raises, leg curls) + PT (eg, box jumps, bouncing, skipping) | 10 | 2 | NA | 3 | NA | NA | 3 |

| Söhnlein 201467 | 12 | 10 | NA | EG: 13.0±0.9; CG: 12.3±0.8 | NA | Soccer | PT (lower body: vertical, horizontal and lateral jumps) | 16 | 2 | NA | 3 | 11 | NA | 2 |

| Tsimachidis 201025* | 13 | 13 | (post-) pubertal | EG: 18.0±1.2; CG:18.0±0.7 | NA | Basketball | CT (eg, squats and sprints) | 10 | 2 | 84 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Weston 201568 | 10 | 10 | NA | EG: 15.7±1.2; CG: 16.7±0.9 | M and F | Swimming | FT (core training: bridge, straight-leg raise; own body weight) | 12 | 3 | NA | 3 | NA | 60 | 2 |

| Wong 201069 | 28 | 23 | NA | EG: 13.5±0.7; CG: 13.2±0.6 | M | Soccer | FW (eg, forward lunge, back half squat, biceps curls) | 12 | 2 | NA | 3 | 9 | 85 | 2 |

| Zribi 201470 | 25 | 26 | prepubertal | EG: 12.1±0.6; CG: 12.2±0.4 | M | Basketball | PT (lower body: DJ, hurdle jumps) | 9 | 2 | NA | 8 | 5 | 180 | 4 |

*Complex training study, reported training parameters referring only to strength-based exercises.

†Seperate training of free weights RT and plyometric training.

CG, control group; CMJ, counter movement jump; CT, complex training; DJ, drop jump; EG, experimental group; F, female; FT, functional training; FW, free weights; M, male; MB, machine based; N Con, number of participants in the control group; N Exp, number of participants in the experimental group; NA, not applicable; PT, plyometric training; Reps, number of repetition per set; Rest, time of rest between sets (seconds); RT, resistance training; Sets, number of sets per exercise; TF, training frequency (times per week); TI, training intensity (% of 1 repetition maximum); TP, training periods (weeks).

There were 13 studies (21 RT intervention groups) that included children, and 29 studies (36 RT intervention groups) that included adolescents. In terms of biological maturation, only 15 studies reported Tanner stages. Three (5 RT intervention groups) of those studies examined prepubertal and 12 (15 RT intervention groups) postpubertal/pubertal youth athletes. Thirty studies (44 RT intervention groups) included boys only, whereas 4 studies (4 RT intervention groups) included girls only.

Youth athletes were recruited from team sports (soccer (20 studies; 34 RT intervention groups), basketball (9 studies; 11 RT intervention groups), baseball (3 studies; 5 RT intervention groups), handball (3 studies; 3 RT intervention groups), tennis (2 studies; 3 RT intervention groups), volleyball (1 study; 1 RT intervention group)), and strength-dominated sports (swimming (3 studies; 3 RT intervention groups), track and field (1 study, 1 RT intervention group)). No included study investigated youth athletes recruited from martial arts or technical/acrobatic sports.

Regarding the type of RT, 4 studies performed RT using machines, 4 studies using free weights, 4 studies using both machines and free weights, 5 studies performed functional RT, 5 studies performed complex training, and 19 studies applied plyometric training. Classification of studies was not always feasible due to missing information or group heterogeneity.

The RT interventions lasted between 4 and 80 weeks, with training frequencies ranging from 1 to 3 sessions per week, 1–8 sets per exercise, 4–15 repetitions per set, and 20–220 s of rest between sets. Training intensity ranged from 35% to 88% of the 1 repetition maximum (RM). Training parameters (eg, temporal distribution of muscle action modes per repetition, and rest in-between repetitions) which have gained attention in the literature71 were not quantified due to insufficient data.

A median PEDro score of 4 (95% CI 4 to 5) was detected and only 4 out of 43 studies reached the predetermined cut-off value of ≥6, which can be interpreted as an overall high risk of bias of the included studies (table 3).

Effectiveness of RT

Table 4 shows the overall as well as age, sex, sport and training type-specific effects of RT on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility and sport-specific performance.

Table 4.

Overall as well as age, sex, sport and training type-specific effects of resistance training in youth athletes

| Muscle strength | Vertical jump performance | Linear sprint performance | Agility | Sport-specific performance | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMDwm | S (I) | N | SMDwm | S (I) | N | SMDwm | S (I) | N | SMDwm | S (I) | N | SMDwm | S (I) | N | |

| All | 1.09 | 16 (23) | 278 | 0.80 | 33 (47) | 702 | 0.58 | 22 (34) | 527 | 0.68 | 14 (25) | 410 | 0.75 | 20 (27) | 345 |

| Maturity | p=NA | p=0.60 | p=0.58 | p=0.99 | p=0.17 | ||||||||||

| Prepubertal (Tanner Stage I and II) | oEG | 0.91 | 3 (5) | 76 | 0.65 | 3 (5) | 76 | 0.58 | 1 (3) | 37 | 0.27 | 1 (3) | 37 | ||

| (Post-) pubertal (tanner stage III–V) | 0.61 | 6 (8) | 90 | 1.15 | 11 (13) | 261 | 0.51 | 4 (6) | 169 | 0.57 | 3 (4) | 149 | 0.72 | 8 (9) | 135 |

| Chronological age | p=0.43 | p=0.74 | p=0.92 | p=0.39 | p=0.05 | ||||||||||

| Children (boys ≤13 years, girls≤11 years) | 1.35 | 3 (4) | 39 | 0.78 | 10 (17) | 235 | 0.55 | 9 (14) | 195 | 0.52 | 6 (11) | 146 | 0.50 | 6 (11) | 153 |

| Adolescence (boys 14–18 years, girls 12–18 years) | 0.91 | 13 (17) | 211 | 0.85 | 22 (28) | 439 | 0.57 | 13 (18) | 302 | 0.71 | 7 (12) | 234 | 1.03 | 13 (15) | 181 |

| Sex | p=0.92 | p=0.54 | p=NA | p=NA | p=0.04 | ||||||||||

| Boys | 1.21 | 12 (18) | 220 | 0.85 | 27 (40) | 615 | 0.63 | 19 (30) | 474 | 0.74 | 12 (22) | 374 | 0.72 | 15 (22) | 288 |

| Girls | oEG | 0.61 | 3 (3) | 37 | oEG | – | 1.81 | 2 (2) | 24 | ||||||

| Sport | p=0.15 | p=0.20 | p=NA | p=NA | p=0.35 | ||||||||||

| Team sports | 1.15 | 13 (20) | 240 | 0.79 | 30 (44) | 662 | 0.58 | 21 (33) | 513 | 0.68 | 14 (25) | 410 | 0.80 | 17 (24) | 312 |

| Martial arts | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Strength-dominant sports | 0.58 | 2 (2) | 24 | 1.22 | 2 (2) | 26 | oEG | – | 0.34 | 3 (3) | 33 | ||||

| Technical/acrobatic sports | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

| Training type | p<0.001 | p=0.41 | p=0.12 | p=0.03 | p=0.02 | ||||||||||

| Machine based | 0.36 | 3 (3) | 36 | 1.45 | 3 (3) | 38 | – | – | 0.30 | 3 (3) | 37 | ||||

| Free weights | 2.97 | 2 (4) | 72 | 0.90 | 3 (5) | 80 | 0.61 | 3 (5) | 80 | 1.31 | 1 (3) | 62 | – | ||

| Machine based and free weights | 1.16 | 4 (6) | 54 | 0.77 | 3 (4) | 39 | 0.18 | 2 (3) | 29 | oEG | oEG | ||||

| Functional training | 0.62 | 2 (3) | 34 | 0.39 | 2 (3) | 52 | 0.19 | 2 (3) | 52 | 0.38 | 2 (3) | 52 | 0.79 | 5 (5) | 84 |

| Complex training | oEG | 1.66 | 4 (5) | 56 | 1.11 | 3 (5) | 38 | 0.66 | 2 (3) | 38 | 1.85 | 2 (3) | 25 | ||

| Plyometric training | 0.39 | 4 (5) | 56 | 0.81 | 16 (25) | 406 | 0.64 | 10 (16) | 300 | 0.62 | 7 (13) | 249 | 0.74 | 10 (15) | 190 |

N, total number of participants in the included experimental groups; NA, not applicable; oEG, only one experimental group; S (I), number of included studies (number of included experimental groups); SMDwm, weighted mean standardised mean difference; y, years.

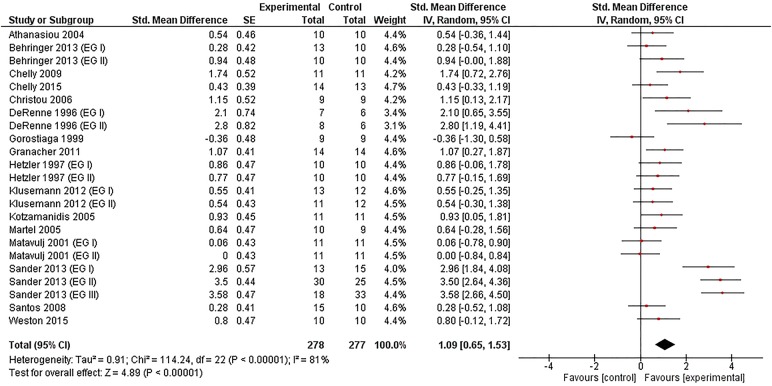

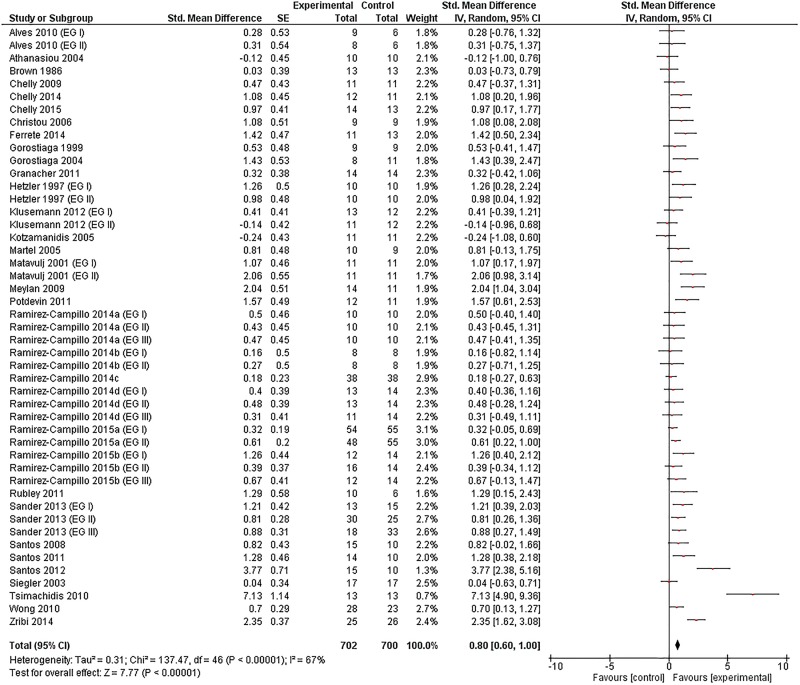

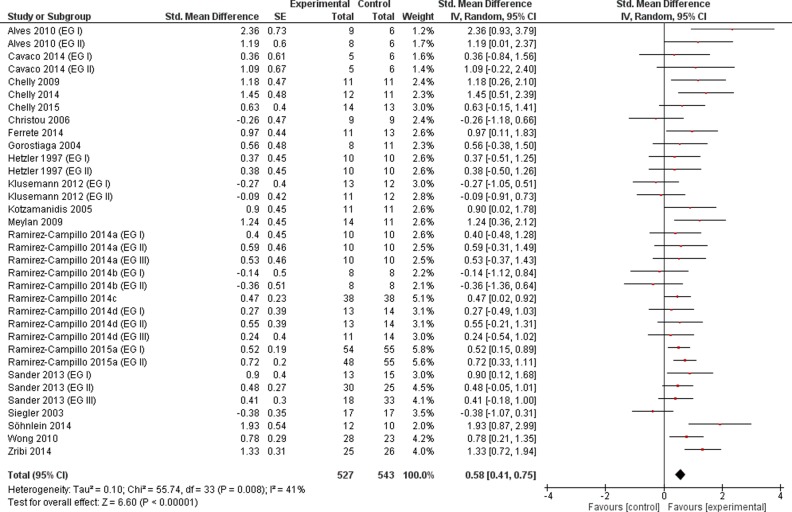

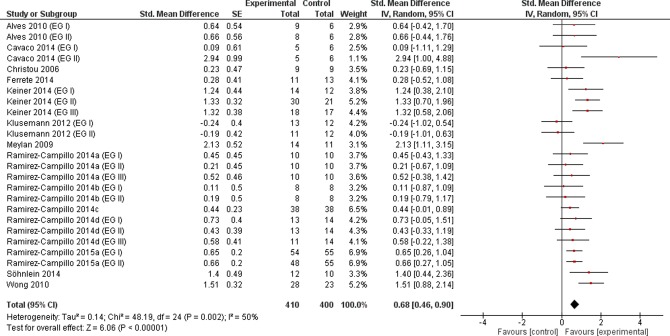

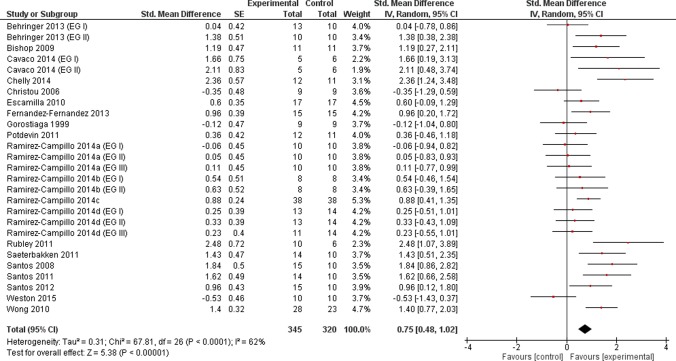

There were moderate effects of RT on measures of muscle strength (SMDwm=1.09; I²=81%; χ2=114.24; df=22; p<0.001; figure 2) and vertical jump performance (SMDwm=0.80; I²=67%; χ2=137.47; df=46; p<0.001; figure 3), while there were small effects for linear sprint performance (SMDwm=0.58; I²=41%; χ2=55.74; df=33; p<0.01; figure 4), agility (SMDwm=0.68; I²=50%; χ2=48.19; df=24; p<0.01; figure 5) and sport-specific performance (SMDwm=0.75; I²=62%; χ2=67.81; df=26; p<0.001; figure 6). By considering only the four studies with high quality (ie, low risk of bias), RT had moderate effects on measures of muscle strength (SMD=1.07; 1 study), vertical jump (SMDwm=0.89; 3 studies) and linear sprint performance (SMDwm=1.19; 2 studies); small effects on agility (SMD=0.28; 1 study); and large effects on sport-specific performance (SMDwm=1.73; 2 studies).

Figure 2.

Effects of resistance training (experimental) versus active control on measures of muscle strength (IV, inverse variance).

Figure 3.

Effects of resistance training (experimental) versus active control on measures of vertical jump performance (IV, inverse variance).

Figure 4.

Effects of resistance training (experimental) versus active control on measures of linear sprint performance (IV, inverse variance).

Figure 5.

Effects of resistance training (experimental) versus active control on agility (IV, inverse variance).

Figure 6.

Effects of resistance training (experimental) versus active control on proxies of sport-specific performance (IV, inverse variance).

There was no statistically significant effect of chronological and/or biological age on any proxy of physical performance. However, a tendency (p=0.05) towards larger RT effects were found for proxies of sport-specific performance in adolescents (SMDwm=1.03) compared with children (SMDwm=0.50; table 4). Subgroup analyses indicated that RT produced significantly larger effects (p<0.05) on proxies of sport-specific performance in girls (SMDwm=1.81) compared with boys (SMDwm=0.72; table 4). Given that most included studies (n=38) examined participants competing in team sports, our subgroup analyses regarding the moderator variable ‘sport’ is limited and did not show any significant subgroup differences (table 4). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that different training types of RT produced significantly different gains in muscle strength (p<0.001), agility (p<0.05) and sport-specific performance (p<0.05). Free weight RT showed the largest effects on muscle strength and agility, while for sport-specific performance, complex training produced the largest effects (table 4).

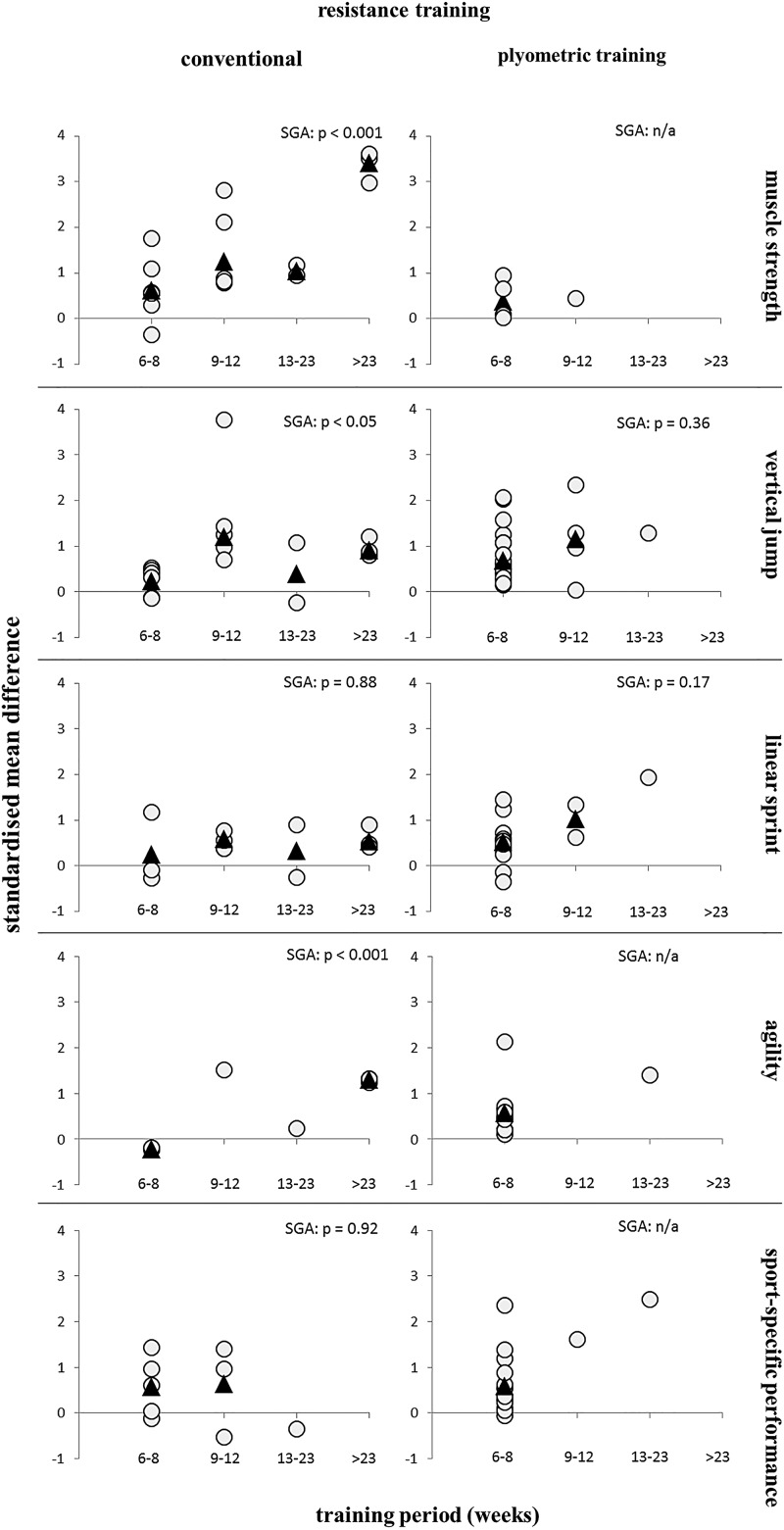

Dose–response relationships of RT

Training period

There was a significant difference for the effects of conventional RT on measures of muscle strength (p<0.001), vertical jump height (p<0.05) and agility (p<0.001; figure 7). The dose–response curves indicated that long lasting conventional RT (>23 training weeks) resulted in more pronounced improvements in measures of muscle strength (SMDwm=3.40) and agility (SMDwm=1.31), as compared with shorter training periods (<23 weeks). In terms of vertical jump height, a training period of 9–12 weeks appeared to be the most effective (SMDwm=1.20).

Figure 7.

Dose–response relationships of the parameter ‘training period’ on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility, and sport-specific performance. Each filled grey circle illustrates between-subject SMD per single study with active control. Filled black triangles represent weighted mean SMD of all studies. NA, not applicable; SGA, subgroup analyses; SMD, standardised mean difference.

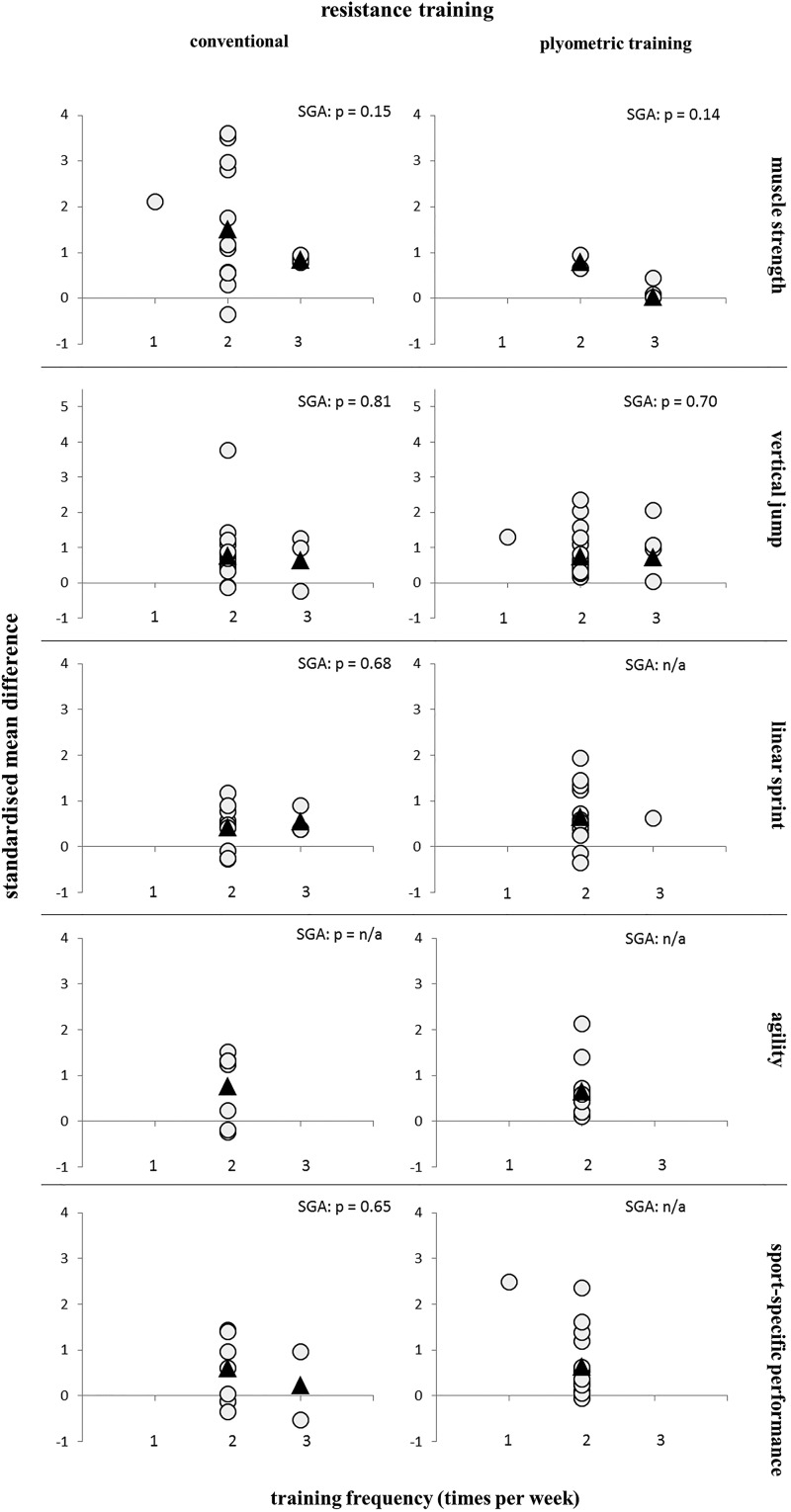

Training frequency

There were no significant differences between the observed training frequencies (ie, 1, 2, 3 times per week) for RT as well as plyometric training (figure 8).

Figure 8.

Dose–response relationships of the parameter ‘training frequency’ on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility, and sport-specific performance. Each filled grey circle illustrates between-subject SMD per single study with active control. Filled black triangles represent weighted mean SMD of all studies. NA, not applicable; SGA, subgroup analyses; SMD, standardised mean difference.

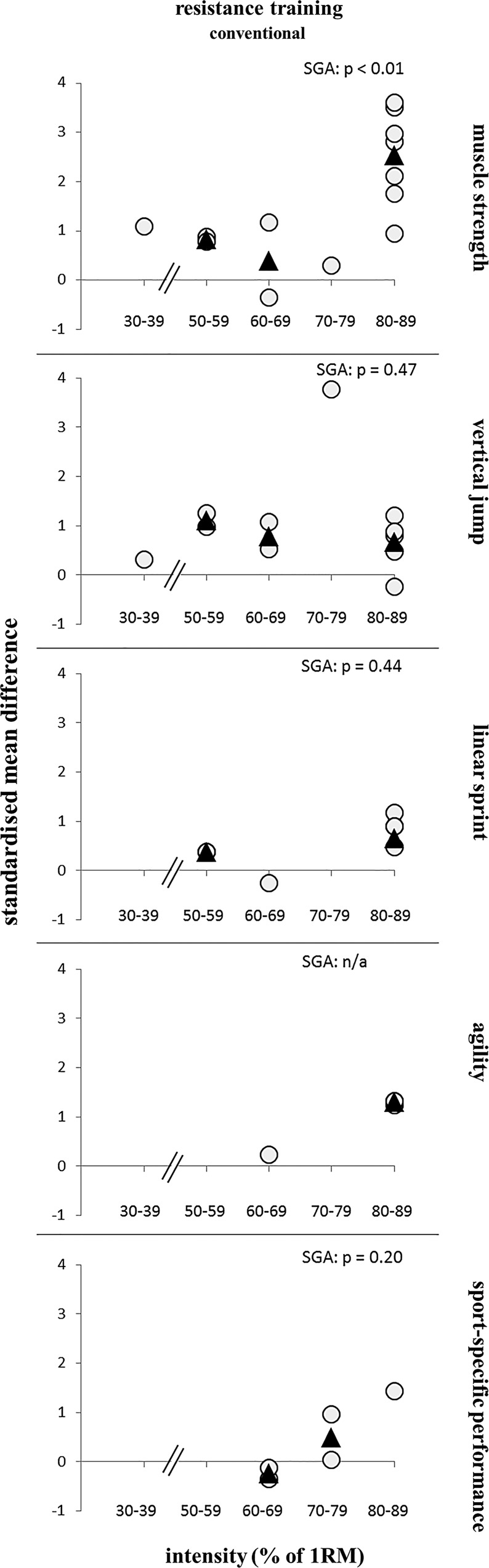

Training intensity

There was a significant difference with regard to the effects of conventional RT on measures of muscle strength (p<0.01; figure 9). High-intensity conventional RT (ie, 80–89% of 1 RM) resulted in more pronounced improvements in muscle strength (SMDwm=2.52) compared with lower training intensities (ie, 30–39%, 40–49%, 50–59%, 60–69%, 70–79% of the 1 RM).

Figure 9.

Dose–response relationships of the parameter ‘training intensity’ on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility, and sport-specific performance. Each filled grey circle illustrates between-subject SMD per single study with active control. Filled black triangles represent weighted mean SMD of all studies. NA, not applicable; SGA, subgroup analyses; SMD, standardised mean difference; RM, repetition maximum.

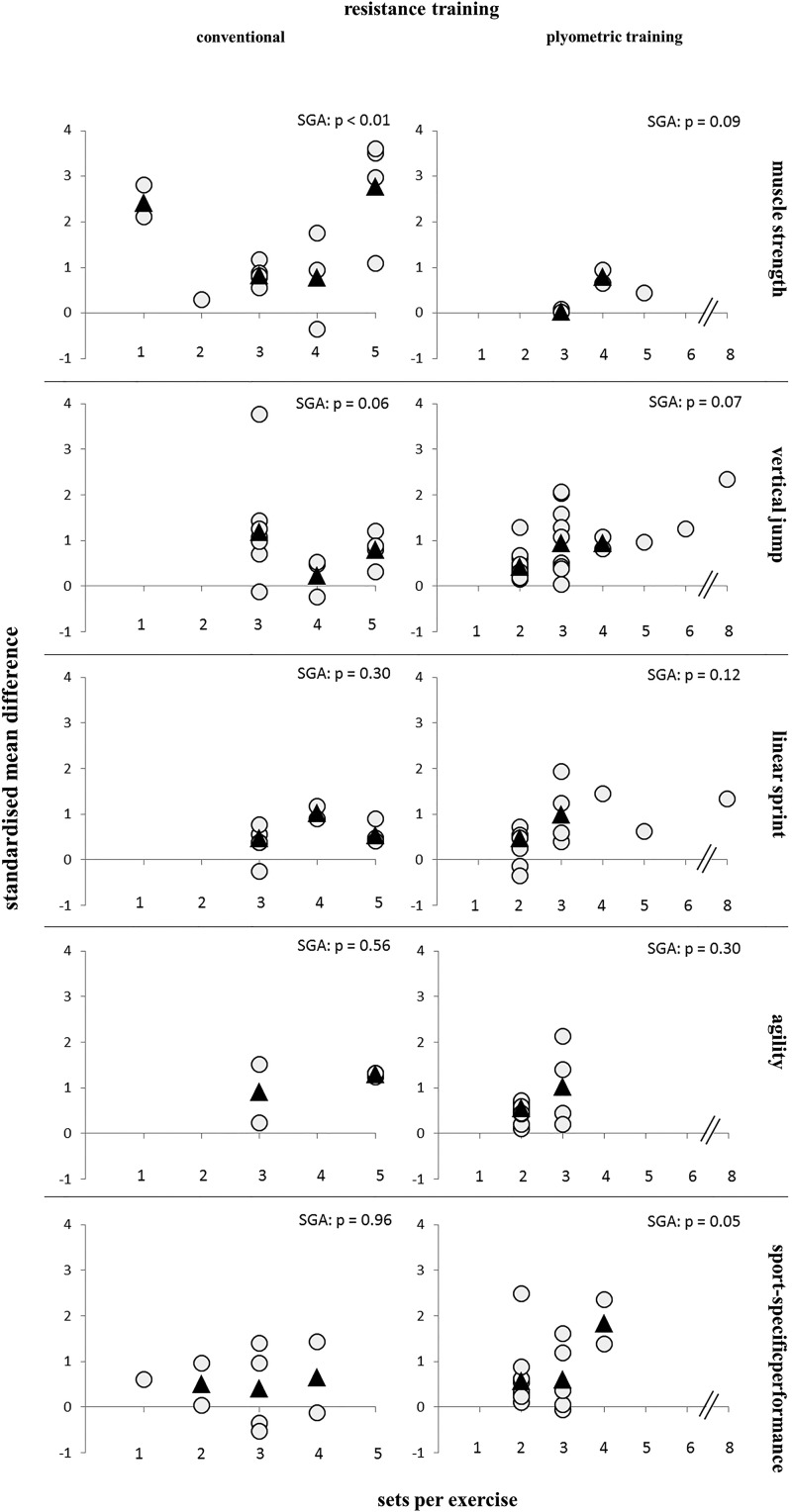

Training volume (number of sets per exercise)

There was a significant difference with regard to the effects of conventional RT on muscle strength (p<0.01), and a tendency towards significance for measures of vertical jump performance (p=0.06; figure 10). Five sets per exercise resulted in more pronounced improvements in muscle strength (SMDwm=2.76) compared with fewer sets. Three sets per exercise tended to be more effective in improving vertical jump performance (SMDwm=1.19), as compared with four or five sets per exercise.

Figure 10.

Dose–response relationships of the parameter ‘sets per exercise’ on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility, and sport-specific performance. Each filled grey circle illustrates between-subject SMD per single study with active control. Filled black triangles represent weighted mean SMD of all studies. NA, not applicable; SGA, subgroup analyses; SMD, standardised mean difference.

For plyometric training, there was a tendency towards larger training-related effects on measures of muscle strength (p=0.09), linear sprint performance (p=0.07), as well as sport-specific performance (p=0.05) depending on the number of sets per exercise. Four sets per exercise revealed the largest effects for measures of muscle strength (SMDwm=0.79) and sport-specific performance (SMDwm=1.84), while three or four sets appear to be most effective for improving linear sprint performance (SMDwm=0.95).

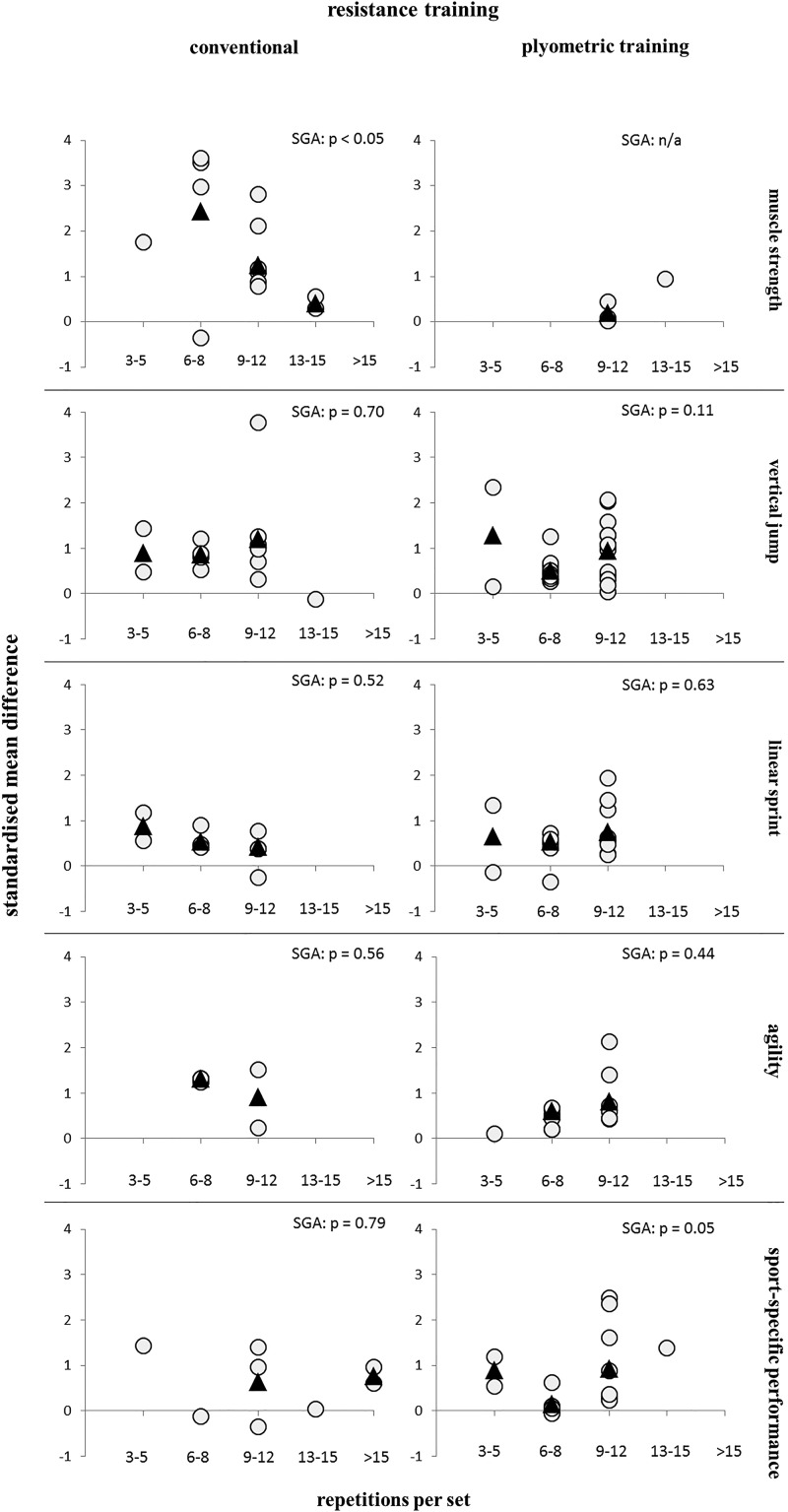

Training volume (number of repetitions per set)

There was a significant difference in terms of the effects of conventional RT on measures of muscle strength (p<0.05; figure 11). Six to eight repetitions per set produced the largest effects on muscle strength (SMDwm=2.42). For plyometric training, there was a tendency towards significance for proxies of sport-specific performance (p=0.05). Six to 8 repetitions per set were less effective (SMDwm=0.15), while 3–5 and 9–12 repetitions per set produced similar effects (SMDwm=0.89 and 0.93).

Figure 11.

Dose–response relationships of the parameter ‘repetitions per set’ on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility, and sport-specific performance. Each filled grey circle illustrates between-subject SMD per single study with active control. Filled black triangles represent weighted mean SMD of all studies. NA, not applicable; SGA, subgroup analyses; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Rest between sets

There was a significant difference for the effects of conventional RT on measures of muscle strength (p<0.05; figure 12). Three to 4 min of rest between sets resulted in more pronounced improvements in measures of muscle strength (SMDwm=2.09), as compared with shorter durations of rest.

Figure 12.

Dose–response relationships of the parameter ‘rest between sets’ on measures of muscle strength, vertical jump and linear sprint performance, agility, and sport-specific performance. Each filled grey circle illustrates between-subject SMD per single study with active control. Filled black triangles represent weighted mean SMD of all studies. NA, not applicable; SGA, subgroup analyses; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Discussion

This systematic review with meta-analysis examined the general effects as well as the age, sex, sport and training type-specific impact of RT on proxies of physical performance in healthy young athletes. In addition, dose–response relationships of RT parameters were independently computed. The main findings were: (1) RT has moderate effects on muscle strength as well as on vertical jump performance, and small effects on linear sprint, agility and sport-specific performance in young athletes, (2) the effects of RT were moderated by the variables sex and RT type, (3) most effective conventional RT programmes to improve measures of muscle strength in healthy young athletes comprised training periods of more than 23 weeks, 5 sets per exercise, 6–8 repetition per set, a training intensity of 80–89% of the 1 RM, and 3–4 min of rest between sets.

Effects of RT on physical performance in youth athletes

In general, RT is an effective way to improve proxies of physical performance in youth athletes, and our findings support recently published literature.4 17 72 73 We found that the main effects of RT on measures of muscle strength and vertical jump performance were moderate in magnitude, with small effects for secondary outcomes, including linear sprint performance, agility and sport-specific performance (eg, throwing velocity). The lower RT effects on secondary outcomes might be explained by the complex nature of these qualities, with various determinants contributing to the performance level. For instance, agility depends on perceptual factors and decision-making as well as on changes in direction of speed, which is again influenced by movement technique, leg muscle quality and straight sprinting speed.74 Thus, muscle strength appears to be only one of several factors contributing to agility.

We recommend the incorporation of RT as an important part of youth athletes’ regular training routine to enhance muscle strength and jump performance.

How age, sex, sport and training type moderate RT effects

Age-specific effects of RT in youth athletes

Biological maturity is related to chronological age, and has a major impact on physical performance in youth athletes.75 However, unlike age, growth and maturation are not linear factors.76 77 There is often a discrepancy between chronological age and biological maturity among youth athletes.4 16 78

We found no significant differences in effect sizes for any proxy of physical performance between prepubertal and postpubertal athletes. Similarly, we did not find significant differences for the effects of RT on any physical performance measure with respect to the moderator variable ‘chronological age’ (table 4). Merely, a tendency (p=0.05) towards higher sport-specific performance gains following RT in adolescents, compared with children, was identified.

Although a minimum age has been defined at which children are mentally and physically ready to comply with coaching instructions,4 our subgroup analyses regarding biological and chronological age suggest that youth athletes may benefit to the same extent from RT, irrespective of age. However, it is important to note that most studies did not report the biological maturity status of the participants. Therefore, more research is needed to elucidate biological age-specific RT effects on physical performance in youth athletes and to verify our preliminary findings.

Sex-specific effects of RT in youth athletes

Previous research on the effects of RT on proxies of physical performance in youth athletes has primarily focused on boys. However, findings from male youth athletes can only partially be transferred to female youth athletes because the physiology of boys and girls (eg, hormonal status during puberty) varies. We found that male and female youth athletes show similar RT-related gains in muscle strength and vertical jump performance, but girls had significantly larger training-induced improvements in sport-specific performance (SMDwm=1.81) compared with boys (SMDwm=0.72). This suggests preliminary evidence that the RT trainability of female adolescent athletes may be at least similar or even higher compared with males. Given that girls’ and boys’ physiology changes differently with age and maturation,76 77 sex-specific effects of RT in youth athletes should be investigated with respect to biological maturity. Owing to an insufficient number of studies that examined female youth athletes and reported their biological maturity status, we were not able to include ‘biological maturity’ as a moderator variable in our subgroup analyses. We consider our sex-specific findings preliminary because these are based on five studies only investigating female youth athletes. More research is needed to elucidate sex-specific RT effects on physical performance in youth athletes and to verify our preliminary findings.

Sport-specific effects of RT in youth athletes

The effects of RT in elite adult athletes may be specifically moderated by the respective athlete profile of the sport performed.79 80 Whether this is also the case in youth athletes remains unresolved. Given that most included studies (n=38) investigated young athletes competing in team sports, our analyses with regard to the moderator variable ‘sport’ was limited and did not reveal any significant differences between sports disciplines (table 4). Therefore, further research has to be conducted to examine if youth athletes respond differently to RT programmes as per the sport practiced.

Training type-specific effects of RT in youth athletes

Various types of RT have been reported (eg, machine-based RT, free weight RT and functional RT). Each of these types has specific benefits and limitations.20 73 Machine-based RT may represent a safe environment for young athletes when supervision cannot be ensured, whereas supervised RT using free weights allows full range of motion that better mimics sports-specific movements.20 73 We found that RT programmes using free weights were most effective to enhance muscular strength and agility. In addition, complex training produced the largest effect sizes if the goal was to improve sport-specific performance. Therefore, the choice of RT types should be variable and based on the exercise goal (eg, enhancing muscle strength or sport-specific performance).

Dose–response relationships of RT in youth athletes

Planning and designing RT programmes is a complex process that requires sophisticated manipulation of different training parameters. Owing to a lack of evidence-based information on dose–response relationships following RT in youth athletes, it is quite common for established and effective RT protocols for healthy untrained children and adolescents to be transferred to youth athletes. However, this may hinder to fully recruit the adaptative potential of young athletes because the optimal dose to elicit the desired effect appears to be different in trained compared with untrained youth.13 Owing to the observed limitations regarding female youth athletes and biological maturation status in the present meta-analysis, the dose–response relationships of RT in youth athletes were determined irrespective of sex and maturity.

In general, the specific configuration of RT parameters determines the underlying training stimulus and thus, the desired physiological adaptations. However, significant effects were predominantly identified for conventional RT parameters for measures of muscle strength. Therefore, it appears that gains in muscular strength may be more sensitive to the applied training parameters of the conventional RT programmes, as compared with the secondary performance outcomes (eg, linear sprint performance, agility, sport-specific performance).

Training period

The effects of short-term (<24 weeks) RT peaked almost consistently with training periods of 9–12 weeks for both conventional RT and plyometric training. However, our subgroup analyses indicated significant differences only for conventional RT for measures of muscle strength and vertical jump performance. Nevertheless, with regard to strength gains, long-term (≥24 weeks) conventional RT was more effective in youth athletes (SMDwm=3.40), as compared with short-term conventional RT (SMDwm=0.61–1.24). Thus, it can be postulated that conventional RT programmes should be incorporated on a regular basis in long-term athlete development.66 Given that continuous performance improvements are difficult to achieve particularly over long time periods, properly varying RT programmes may avert training plateaus, maximise performance gains and reduce the likelihood of overtraining.

Regular basketball practice during a detraining/reduced training period was sufficient to maintain previously achieved muscular power gains due to its predominantly power-type training drills.81 Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesise that regular training can maintain RT-based gains in muscular strength for several weeks if similar physical demands are addressed during regular training. Coaches may reduce the time spent on RT for several weeks without impairing previously achieved strength gains during competition periods when the training must emphasise motor skills and competition demands.

Training frequency

The phase of periodisation, projected exercise loads and the dose of additional physical training (ie, overall amount of physical stress) may influence training frequency.21 In order to avoid overtraining and achieve maximal benefits of RT, it is important to allow the body sufficient time to recover from each RT session. However, if the rest between RT sessions is too long, adaptive processes from previous RT sessions may get lost.

Most studies performed RT two or three times per week (figure 8), and there was no significant difference between the observed training frequencies. To our knowledge, there is no study available that directly compared the effects of two RT sessions per week as opposed to three sessions for youth athletes. Although a reduced RT frequency of one session per week may be sufficient to maintain muscle strength gains following RT for several weeks,41 82 training twice per week might be preferred to achieve further gains in muscle strength in youth athletes.

Training volume and training intensity

Both volume and intensity have to be considered when prescribing RT to maximise physiological adaptations and minimise injury risk.4 Different configurations of training volume and intensity result in different forms of physiological stress, which in turn induce different neural and muscular adaptations.71

Owing to the large methodological variety in dealing with training intensity during plyometric training, we were not able to consistently quantify the dose–response relationship for training intensity with regard to plyometric training.

Conventional RT programmes using average training intensities of 80–89% of the 1 RM were most beneficial in terms of improving muscle strength in youth athletes. These findings are in accordance with the position stand of the American College of Sports Medicine for strength training in adults.83 The largest effect sizes for muscle strength gains in adults, trained individuals and athletes were achieved at 80–85% of the 1 RM.8 12 However, it should be noted that the individual percentage of 1 RM is a stress rather than a strain factor. Several studies have indicated that a given number of repetitions cannot be associated with a specific percentage rate of the 1 RM.78 84 Thus, to individualise RT, future studies should focus on finding a valid strain-based method to quantify RT intensity effectively.

In terms of the number of sets per conventional RT exercise, our data show similar effect size magnitudes when comparing single-set (SMDwm=2.41) versus multiple-set conventional RT programmes (5 sets: SMDwm=2.76). The primary benefit of a single-set conventional RT is time efficiency. Nevertheless, since our results for single-set conventional RT are based on two intervention groups from one study, this finding has to be interpreted with caution. Although there was no study that directly compared the effects of single-set versus multiple-set conventional RT in youth athletes, there is evidence from adult athletes that single-set conventional RT may be appropriate during the initial phase of RT,85 whereas multiple-set conventional RT programmes should be used to promote further gains in muscle strength, especially in athletes.86 Therefore, multiple-set conventional RT may be necessary to elicit sufficient training stimuli during long-term youth athlete development.

Regarding the applied plyometric training, 3 (for vertical jump) or 4 sets per exercise (for muscle strength, sport-specific performance) as well as 3–5 or 9–12 repetitions per set (for vertical jump, sport-specific performance) might be beneficial for youth athletes’ physical performance. However, the movement quality of plyometric exercises is more important than the total session volume.87 Therefore, we recommend the use of thresholds for performance variables, such as ground contact time or performance indices, to determine individualised training volume.87

Rest between sets

The duration of rest between sets and repetitions depends on parameters like training intensity and volume. The rest interval significantly affects the biochemical responses following RT.71 Owing to an insufficient number of studies that reported the duration of rest between repetitions, we focused on dose–response relationships for rest between sets. Long rest periods (ie, 3–4 min of rest between sets) were most effective for improving muscle strength following conventional RT in youth athletes. This is most likely because long rest periods allow athletes to withstand higher volumes and intensities during training.

Limitations of this meta-analysis

A major limitation is that we could not provide insights into the interactions between the reported training parameters. Our analyses are based on a variety of studies using different combinations of training parameters magnitudes (eg, training frequency, number of sets, intensity). It remains unclear if performance gains would still be maximal if, according to the present dose–response relationships, the optimum of each parameter was implemented in RT programmes.81 Thus, further research is necessary to find an analytical method to provide insights into the interactions between the investigated training parameters. The modelling of training variables might help to address this limitation. Holding a set of RT variables constant while changing the effects of one specific variable could determine the unique effects of each training variable.

Further limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis are the high risk of bias of the included studies (only 4 out of 43 studies reached a PEDro score of ≥6), the considerable heterogeneity between studies (ie, I²=41–81%), and the uneven distribution of SMDs calculated for the respective training parameters. In addition, the scale for determining the magnitude of effect sizes32 is not specific for RT research in children and adolescents. Another limitation is that almost all studies failed to report RT parameters which had got recent research attention (eg, temporal distribution of muscle action modes per repetition).71 Further, studies used traditional stress-based (ie, RM) instead of recent strain-based (eg, OMNI resistance exercise scale of perceived exertion88) methods to quantify RT intensity.89 We were not able to aggregate the effects of moderator variables, such as sex and maturation, for the dose–response relationships due to an insufficient number of studies that specifically addressed these issues.

Summary

RT was effective for improving proxies of physical performance in youth athletes. The magnitudes of RT effects were moderate in terms of measures of muscle strength and vertical jump performance, and small with regard to measures of linear sprint, agility and sports-specific performance in youth athletes. Sex and RT type appeared to moderate these effects. However, most studies were at high risk of bias and therefore, the results should be interpreted cautiously.

A training period of more than 23 weeks, 5 sets per exercise, 6–8 repetitions per set, a training intensity of 80–89% of 1 RM, and 3–4 min rest between sets were most effective for conventional RT programmes to improve muscle strength in youth athletes. However, these evidence-based findings should be adapted individually by considering individual abilities, skills and goals. Specifically, youth coaches should not use high RT intensities before the youth athlete developed technical skills to adequately perform the RT exercises.

What is already known on this topic?

Resistance training is safe for children and adolescents if appropriately prescribed and supervised.

Several meta-analyses have already shown that resistance training has the potential to improve muscle strength and motor skills (eg, jump performance) in healthy, untrained children and adolescents.

What this study adds.

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to examine age, sex, sport and training type-specific effects of resistance training on physical performance measures in youth athletes.

The effect of resistance training was moderated by sex and resistance training type. Girls had greater training-related sport-specific performance gains compared with boys, and resistance training programmes with free weights were most effective for increasing muscle strength.

Dose–response relationships for key training parameters indicate that youth coaches should aim for resistance training programmes with fewer repetitions and higher intensities to improve physical performance measures.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Andrea Horn for her support during the course of the research project.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML, OP and UG performed systematic literature search and wrote the paper. ML and OP analysed the data.

Funding: This study is part of the research project ‘Resistance Training in Youth Athletes’ that was funded by the German Federal Institute of Sport Science (ZMVI1-081901 14-18).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Behringer M, Vom Heede A, Matthews M, et al. Effects of strength training on motor performance skills in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2011;23:186–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Resistance training among young athletes: safety, efficacy and injury prevention effects. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:56–63. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.068098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faigenbaum AD. Resistance training for children and adolescents: are there health outcomes? Am J Lifestyle Med 2007;1:190–200. 10.1177/1559827606296814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd RS, Faigenbaum AD, Stone MH, et al. Position statement on youth resistance training: the 2014 international consensus. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:498–505. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behringer M, Vom Heede A, Yue Z, et al. Effects of resistance training in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2010;126:e1199–210. 10.1542/peds.2010-0445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falk B, Tenenbaum G. The effectiveness of resistance training in children. A meta-analysis. Sports Med 1996;22:176–86. 10.2165/00007256-199622030-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payne VG, Morrow JR, Johnson L, et al. Resistance training in children and youth: a meta-analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport 1997;68:80–8. 10.1080/02701367.1997.10608869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson MD, Rhea MR, Alvar BA. Maximizing strength development in athletes: a meta-analysis to determine the dose-response relationship. J Strength Cond Res 2004;18:377–82. 10.1519/R-12842.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergeron MF, Mountjoy M, Armstrong N, et al. International olympic committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:843–51. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson MD, Rhea MR, Alvar BA. Applications of the dose-response for muscular strength development: a review of meta-analytic efficacy and reliability for designing training prescription. J Strength Cond Res 2005;19:950–8. 10.1519/R-16874.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harries SK, Lubans DR, Callister R. Resistance training to improve power and sports performance in adolescent athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport 2012;15:532–40. 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhea MR, Alvar BA, Burkett LN, et al. A meta-analysis to determine the dose response for strength development. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:456–64. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000053727.63505.D4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faigenbaum AD, Lloyd RS, Myer GD. Youth resistance training: past practices, new perspectives, and future directions. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2013;25:591–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaughn JM, Micheli L. Strength training recommendations for the young athlete. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2008;19:235–45. 10.1016/j.pmr.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behm DG, Faigenbaum AD, Falk B, et al. Canadian society for exercise physiology position paper: resistance training in children and adolescents. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2008;33:547–61. 10.1139/H08-020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faigenbaum AD, Lloyd RS, MacDonald J, et al. Citius, Altius, Fortius: beneficial effects of resistance training for young athletes: narrative review. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:3–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faigenbaum AD, Kraemer WJ, Blimkie CJ, et al. Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the national strength and conditioning association. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:S60–79. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31819df407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matos N, Winsley RJ. Trainability of young athletes and overtraining. J Sports Sci Med 2007;6:353–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faigenbaum A, Westcott WL. Youth strength training. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baechle TR, Earle RW. Essentials of strength training and conditioning- National strength & conditioning association. 3rd edn Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesinski M, Muehlbauer T, Busch D, et al. [Effects of complex training on strength and speed performance in athletes: a systematic review]. Sportverletz Sportschaden 2014;28:85–107. 10.1055/s-0034-1366145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavaco B, Sousa N, Dos Reis VM, et al. Short-term effects of complex training on agility with the ball, speed, efficiency of crossing and shooting in youth soccer players. J Hum Kinet 2014;43:105–12. 10.2478/hukin-2014-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrete C, Requena B, Suarez-Arrones L, et al. Effect of strength and high-intensity training on jumping, sprinting, and intermittent endurance performance in prepubertal soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:413–22. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31829b2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsimahidis K, Galazoulas C, Skoufas D, et al. The effect of sprinting after each set of heavy resistance training on the running speed and jumping performance of young basketball players. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:2102–8. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e2e1ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos EJ, Janeira MA. Effects of complex training on explosive strength in adolescent male basketball players. J Strength Cond Res 2008;22:903–9. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31816a59f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maio Alves JM, Rebelo AN, Abrantes C, et al. Short-term effects of complex and contrast training in soccer players’ vertical jump, sprint, and agility abilities. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:936–41. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c7c5fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, et al. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2003;83:713–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgings JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic review of interventions version 5.1.0. Collaboration SMGoTC, 2010:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deeks JJ, Higgings JPT. Statistical algorithms in Review Manager 5. 2010.

- 32.Rhea MR. Determining the magnitude of treatment effects in strength training research through the use of the effect size. J Strength Cond Res 2004;18:918–20. 10.1519/14403.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Athanasiou N, Tsamourtzis E, Salonikidis K. Entwicklung und Trainierbarkeit der Kraft bei Basketballspielern im vorpubertären Alter. Leistungssport 2006;1:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behringer M, Neuerburg S, Matthews M, et al. Effects of two different resistance-training programs on mean tennis-serve velocity in adolescents. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2013;25:370–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bishop DC, Smith RJ, Smith MF, et al. Effect of plyometric training on swimming block start performance in adolescents. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:2137–43. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b866d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown ME, Mayhew JL, Boleach LW. Effect of plyometric training on vertical jump performance in high school basketball players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1986;26:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chelly MS, Fathloun M, Cherif N, et al. Effects of a back squat training program on leg power, jump, and sprint performances in junior soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:2241–9. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b86c40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chelly MS, Hermassi S, Aouadi R, et al. Effects of 8-week in-season plyometric training on upper and lower limb performance of elite adolescent handball players. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:1401–10. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chelly MS, Hermassi S, Shephard RJ. Effects of in-season short-term plyometric training program on sprint and jump performance of young male track athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:2128–36. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christou M, Smilios I, Sotiropoulos K, et al. Effects of resistance training on the physical capacities of adolescent soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2006;20:783–91. 10.1519/R-17254.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeRenne C, Hetzler RK, Buxton BP, et al. Effects of training frequency on strength maintenance in pubescent baseball players. J Strength Cond Res 1996;10:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Yamashiro K, et al. Effects of a 4-week youth baseball conditioning program on throwing velocity. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:3247–54. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181db9f59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandez-Fernandez J, Ellenbecker T, Sanz R, et al. Effects of a 6-week junior tennis conditioning program on service velocity. J Sports Sci Med 2013;12:232–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorostiaga EM, Izquierdo M, Iturralde P, et al. Effects of heavy resistance training on maximal and explosive force production, endurance and serum hormones in adolescent handball players. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1999;80:485–93. 10.1007/s004210050622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorostiaga EM, Izquierdo M, Ruesta M, et al. Strength training effects on physical performance and serum hormones in young soccer players. Eur J Appl Physiol 2004;91:698–707. 10.1007/s00421-003-1032-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Granacher U, Muehlbauer T, Doerflinger B, et al. Promoting strength and balance in adolescents during physical education: effects of a short-term resistance training. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:940–9. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c7bb1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hetzler RK, DeRenne C, Buxton BP, et al. Effects of 12 weeks of strength training on anaerobic power in prepubescent male athletes. J Strength Cond Res 1997;11:174–81. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keiner M, Sander A, Wirth K, et al. Long-term strength training effects on change-of-direction sprint performance. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:223–31. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318295644b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klusemann MJ, Pyne DB, Fay TS, et al. Online video-based resistance training improves the physical capacity of junior basketball athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2012;26:2677–84. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318241b021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kotzamanidis C, Chatzopoulos D, Michailidis C, et al. The effect of a combined high-intensity strength and speed training program on the running and jumping ability of soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2005;19:369–75. 10.1519/R-14944.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martel GF, Harmer ML, Logan JM, et al. Aquatic plyometric training increases vertical jump in female volleyball players. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37:1814–19. 10.1249/01.mss.0000184289.87574.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matavulj D, Kukolj M, Ugarkovic D, et al. Effects of plyometric training on jumping performance in junior basketball players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2001;41:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meylan C, Malatesta D. Effects of in-season plyometric training within soccer practice on explosive actions of young players. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:2605–13. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b1f330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Potdevin FJ, Alberty ME, Chevutschi A, et al. Effects of a 6-week plyometric training program on performances in pubescent swimmers. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:80–6. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181fef720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramirez-Campillo R, Gallardo F, Henriquez-Olguin C, et al. Effect of vertical, horizontal, and combined plyometric training on explosive, balance, and endurance performance of young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:1784–95. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramirez-Campillo R, Henriquez-Olguin C, Burgos C, et al. Effect of progressive volume-based overload during plyometric training on explosive and endurance performance in Young Soccer Players. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:1884–93. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramirez-Campillo R, Meylan C, Alvarez C, et al. Effects of in-season low-volume high-intensity plyometric training on explosive actions and endurance of young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:1335–42. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramirez-Campillo R, Andrade DC, Álvarez C, et al. The effects of interset rest on adaptation to 7 weeks of explosive training in young soccer players. J Sports Sci Med 2014;13:287–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramirez-Campillo R, Meylan CM, Alvarez-Lepin C, et al. The effects of interday rest on adaptation to 6 weeks of plyometric training in young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:972–9. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramirez-Campillo R, Burgos CH, Henriquez-Olguin C, et al. Effect of unilateral, bilateral, and combined plyometric training on explosive and endurance performance of young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2015;29:1317–28. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rubley MD, Haase AC, Holcomb WR, et al. The effect of plyometric training on power and kicking distance in female adolescent soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:129–34. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b94a3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saeterbakken AH, van den Tillaar R, Seiler S. Effect of core stability training on throwing velocity in female handball players. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25: 712–18. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181cc227e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sander A, Keiner M, Wirth K, et al. Influence of a 2-year strength training programme on power performance in elite youth soccer players. Eur J Sport Sci 2013;13:445–51. 10.1080/17461391.2012.742572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santos EJ, Janeira MA. The effects of plyometric training followed by detraining and reduced training periods on explosive strength in adolescent male basketball players. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:441–52. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b62be3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santos EJ, Janeira MA. The effects of resistance training on explosive strength indicators in adolescent basketball players. J Strength Cond Res 2012;26:2641–7. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823f8dd4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siegler J, Gaskill S, Ruby B. Changes evaluated in soccer-specific power endurance either with or without a 10-week, in-season, intermittent, high-intensity training protocol. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Söhnlein Q, Muller E, Stoggl TL. The effect of 16-week plyometric training on explosive actions in early to mid-puberty elite soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:2105–14. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weston M, Hibbs AE, Thompson KG, et al. Isolated core training improves sprint performance in national-level junior swimmers. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015;10:204–10. 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong PL, Chamari K, Wisloff U. Effects of 12-week on-field combined strength and power training on physical performance among U-14 young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:644–52. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ad3349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zribi A, Zouch M, Chaari H, et al. Short-term lower-body plyometric training improves whole-body BMC, bone metabolic markers, and physical fitness in early pubertal male basketball players. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2014;26:22–32. 10.1123/pes.2013-0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toigo M, Boutellier U. New fundamental resistance exercise determinants of molecular and cellular muscle adaptations. Eur J Appl Physiol 2006;97:643–63. 10.1007/s00421-006-0238-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mountjoy M, Armstrong N, Bizzini L, et al. IOC consensus statement: “training the elite child athlete”. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:163–4. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Myer D, Wall E. Resistance training in the young athlete. Op Tech Sports Med 2006;14:218–30. 10.1053/j.otsm.2006.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Young WB, James R, Montgomery I. Is muscle power related to running speed with changes of direction? J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2002;42:282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Engebretsen L, Steffen K, Bahr R, et al. The International Olympic Committee consensus statement on age determination in high-level young athletes. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:476–84. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.073122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Armstrong N, McManus AM. Physiology of elite young male athletes. Med Sport Sci 2011;56:1–22. 10.1159/000320618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McManus AM, Armstrong N. Physiology of elite young female athletes. Med Sport Sci 2011;56:23–46. 10.1159/000320626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buskies W, Boeckh-Behrens W-U. Probleme bei der Steuerung der Trainingsintensität im Krafttraining auf der Basis von Maximalkrafttests. Leistungssport 1999;3:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilson JM, Loenneke JP, Jo E, et al. The effects of endurance, strength, and power training on muscle fiber type shifting. J Strength Cond Res 2012;26:1724–9. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318234eb6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Karp JR. Muscle fibre types and training. Track Coach 2001;155:4943–6. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arandjelovic O. A mathematical model of neuromuscular adaptation to resistance training and its application in a computer simulation of accommodating loads. Eur J Appl Physiol 2010;110:523–38. 10.1007/s00421-010-1526-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Santos EJ, Janeira MA. Effects of reduced training and detraining on upper and lower body explosive strength in adolescent male basketball players. J Strength Cond Res 2009;23:1737–44. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b3dc9d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:687–708. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marschall F, Fröhlich M. Überprüfung des Zusammenhangs von Maximalkraft und maximaler Wiederholungszahl bei deduzierten submaximalen Intensitäten. Deutsche Zeit Sportmed 1999;50:311–15. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wolfe BL, LeMura LM, Cole PJ. Quantitative analysis of single- vs. multiple-set programs in resistance training. J Strength Cond Res 2004;18:35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:674–88. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000121945.36635.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lloyd RS, Meyers RW, Oliver JL. The natural development and trainability of plyometric ability during childhood. Strength Cond J 2011;33:23–32. 10.1519/SSC.0b013e3182093a27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robertson RJ, Goss FL, Rutkowski J, et al. Concurrent validation of the OMNI perceived exertion scale for resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:333–41. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048831.15016.2A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marschall F, Buesch D. Positionspapier für eine beanspruchungsorientierte Trainingsgestaltung im Krafttraining. Schweiz Z Sportmed Sporttraumatol 2014;62:24–31. [Google Scholar]