Abstract

Background

The influence of social relationships on morbidity is widely accepted, but the size of the risk to cardiovascular health is unclear.

Objective

We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the association between loneliness or social isolation and incident coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke.

Methods

Sixteen electronic databases were systematically searched for longitudinal studies set in high-income countries and published up until May 2015. Two independent reviewers screened studies for inclusion and extracted data. We assessed quality using a component approach and pooled data for analysis using random effects models.

Results

Of the 35 925 records retrieved, 23 papers met inclusion criteria for the narrative review. They reported data from 16 longitudinal datasets, for a total of 4628 CHD and 3002 stroke events recorded over follow-up periods ranging from 3 to 21 years. Reports of 11 CHD studies and 8 stroke studies provided data suitable for meta-analysis. Poor social relationships were associated with a 29% increase in risk of incident CHD (pooled relative risk: 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.59) and a 32% increase in risk of stroke (pooled relative risk: 1.32, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.68). Subgroup analyses did not identify any differences by gender.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that deficiencies in social relationships are associated with an increased risk of developing CHD and stroke. Future studies are needed to investigate whether interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation can help to prevent two of the leading causes of death and disability in high-income countries.

Study registration number

CRD42014010225.

Introduction

Adults who have few social contacts (ie, who are socially isolated) or feel unhappy about their social relationships (ie, who are lonely) are at increased risk of premature mortality.1 The influence of social relationships on mortality is comparable with well-established risk factors, including physical activity and obesity.2 Yet, compared with our understanding of these risk factors, we know much less about the implications of loneliness and social isolation for disease aetiology.

Researchers have identified three main pathways through which social relationships may affect health: behavioural, psychological and physiological mechanisms.3 4 Health-risk behaviours associated with loneliness and social isolation include physical inactivity and smoking.5 Loneliness is linked to lower self-esteem and limited use of active coping methods,6 while social isolation predicts decline in self-efficacy.7 Feeling lonely or being socially isolated is associated with defective immune functioning and higher blood pressure.8 9 This evidence suggests that loneliness and social isolation may be important risk factors for developing disease, and that addressing them would benefit public health and well-being.

The aim of this study was to investigate the size of the association between deficiencies in social relationships and incident coronary heart disease (CHD) or stroke, the two greatest causes of burden of disease in high-income countries.10 We conducted a systematic review to answer the following primary question: are deficiencies in social relationships associated with developing CHD and stroke in high-income countries? Our secondary objectives included investigating whether loneliness or social isolation was differentially associated with incident heart disease and stroke, and whether the association between social relationships and disease incidence varied according to age, gender, marital status, socioeconomic position, ethnicity and health.

Methods

This study followed the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination's Guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare.11 A protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42014010225).12

Study eligibility criteria

To meet inclusion criteria, studies had to investigate new CHD and/or stroke diagnosis at the individual level as a function of loneliness and/or social isolation. We defined CHD as encompassing the diagnoses listed under codes l20–l25 of the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), and stroke as ICD-10 codes I60–69. We excluded studies where CHD or stroke diagnosis was not the first instance of diagnosis among participants, except where analyses controlled for previous events. We applied no other exclusion criteria regarding study population. Measures of social relationships met inclusion criteria for loneliness if they were consistent with its definition as a subjective negative feeling associated with someone's perception that their relationships with others are deficient.13 Measures of social isolation had to be consistent with its definition as a more objective measure of the absence of relationships, ties or contact with others.14 We focused on longitudinal studies in order to investigate the temporal relationships between loneliness or isolation and subsequent disease. Our purpose was to clarify the public health challenge posed by deficiencies in social relationships in high-income countries,15 so we excluded all other settings. We applied no language, publication type or date restrictions to inclusion.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched 16 electronic databases for published and grey literature published up until May 2015: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, ASSIA, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Social Policy and Practice, National Database of Ageing Research, Open Grey, HMIC, ETHOS, NDLTD, NHS Evidence, SCIE and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Thesaurus and free text terms (eg, loneliness, social isolation, social relationships, social support, social network) were combined with filters for observational study designs and tailored to each database. The search strategy included no health terms, as it aimed to capture all disease outcomes, rather than focus on CHD and stroke. For the full electronic strategy used to search MEDLINE, see online supplementary appendix 1.

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix1.pdf (99.3KB, pdf)

To complement the electronic search, we screened reference lists, searched for citations in Scopus (the largest database of abstracts and citations) and contacted topic experts identified through the UK Campaign to End Loneliness’ Research Hub.

After removing duplicates, two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts before assessing full records using a standardised screening sheet. Additional information was sought from authors when necessary (3 (60%) responded). When authors did not reply, we searched for information from related publications to inform our decision.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted into a standardised form by one researcher, and checked by a second. Study authors were contacted to obtain missing data.

Based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality framework and taxonomy of threats to validity and precision,16 we selected the following domains as relevant for assessing studies: sampling bias, non-response bias, missing data, differential loss to follow-up, information error with regard to exposure and outcome measure, detection bias, confounding and study size. We identified age, gender and socioeconomic status as potential confounders (ie, factors correlated with exposure, predictive of outcome and not on the causal pathway).17 18 No studies were excluded due to quality; instead, subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed, to test the stability of findings according to internal validity.

Quantitative synthesis

We hypothesised that social relationships were associated with disease incidence, and that this association may differ according to the dimension of relationships measured, and individual-level and contextual-level factors. A preliminary synthesis was developed by grouping study characteristics and results according to their measure of relationships. The majority of papers reported relative hazards of new diagnosis, comparing people with higher versus lower levels of loneliness or social isolation. Since incidence of disease was low (<10%) in the three studies reporting ORs, these estimates were approximated to relative risks.19 Where the lonely or isolated group was used as the reference, results were transformed to allow comparison across studies.

Patterns identified in the preliminary synthesis were formally investigated. Only papers for which an effect estimate and SE or CI were available (reported in the paper or provided by contacted authors), or could be calculated, contributed to this stage of the analysis. Where several papers reported results from the same cohort, we privileged the findings with the longest follow-up time. If a study included multiple measures of exposure and/or outcome, we selected the result relating to the most comprehensive measure. Where a study used statistical controls to calculate an effect size, we extracted data from the most complex model to minimise risk of confounding. All effect sizes were transformed to the natural log for analyses. Using Revman V.5.3 (Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.3 [program]. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, 2014), CHD and stroke effect estimates were plotted in separate forest plots, and heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic.

Potential sources of variation were explored with prespecified subgroup analyses. Since heterogeneity could not be explained and removed based on these analyses, but we deemed studies sufficiently similar to warrant aggregation, we combined results using random effects models. This approach allows for between-study variation, and is consistent with our assumption that the effects estimated in the different studies were not identical, since they investigated different dimensions of social relationships and derived from different populations.

Finally, sensitivity analyses were performed to test whether our overall results were affected by internal study validity and small-study effects. Contour-enhanced funnel plots for asymmetry were drawn using STATA V.12 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 [program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2011). The limited number and the heterogeneity of studies did not support the use of tests for funnel plot asymmetry.20

Results

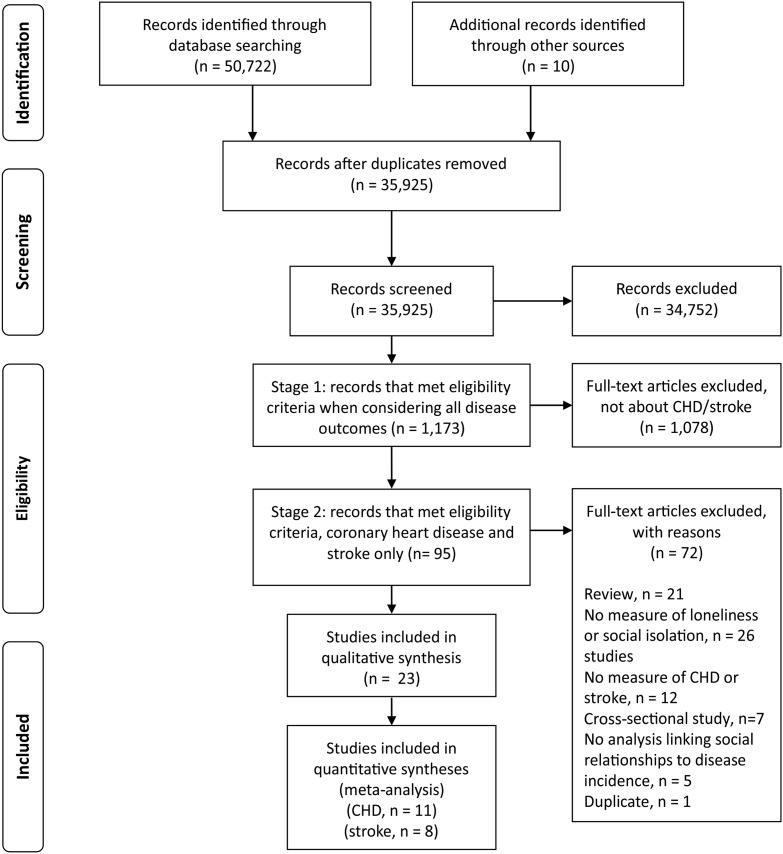

A total of 23 studies based on 16 cohorts were identified for inclusion in the review, after a two-stage process. See figure 1 for a flow diagram of the study selection process. Eleven studies on CHD and eight studies on stroke met inclusion criteria for the quantitative syntheses (ie, studies based on independent samples reporting data from which the natural log of the estimate and its SE could derived).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. CHD, coronary heart disease.

Table 1 summarises the descriptive characteristics of the evidence included in our review (see online supplementary appendix 2 for individual study characteristics).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included evidence

| Population characteristics across included studies | |

| Total number of participants | 181 006 |

| Age of participants | 18 and over |

| Breakdown of the population according to world region |

|

| Study characteristics | |

| Baseline data collection years, range | 1965–1996 |

| Length of follow-up, range | 3–21 years |

| Size, range | Between 98 and 47 713 subjects |

| Gender | |

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix2.pdf (136.3KB, pdf)

Assessment of loneliness and social isolation

Prevalence of loneliness or social isolation ranged from 2.8%40 to 77.2%.31 Three papers measured loneliness,21 30 42 18 measured social isolation22–43 and two papers used a measure combining both dimensions.34 35 The three papers on loneliness used different tools: a direct question asking about loneliness feelings during the day,30 a question on feelings of loneliness in the past week42 and a 13-item tool encompassing the perceived availability, adequacy or accessibility of social relationships.21 Across the 18 studies on social isolation, 11 tools were used: six studies used the Berkman–Syme Social Network Index,44 two studies used the 10-item Lubben Social Network Scale45 and the remainder used nine different tools on the availability and/or frequency of contacts. One cohort study used a measure combining social isolation and loneliness, the 11-item Duke Social Support Index, which asks about frequency of interaction and satisfaction with relationships.46

Loneliness and social isolation were predominantly treated as a categorical variable; two studies analysed them as continuous variables.29 42 Only one study reported results based on measuring social relationships more than once.42

Ascertainment of CHD and stroke

A total of 4628 CHD and 3002 stroke events were recorded across the 23 papers. Eighteen studies measured incident CHD and 10 measured stroke (five studies reported on both outcomes). Diagnosis was ascertained from medical records, death certificates or national registers in all but four studies. Others used self-report,34 35 or telephone interviews with a nurse or physician.33 Two studies verified self-reported events against medical records.29 36 38 The majority of studies with a measure of CHD focused on myocardial infarction and/or CHD death (11/18). Four studies included angina pectoris within their measure of CHD and two presented results for angina separately. The remit of the CHD measure was unclear in one study.43

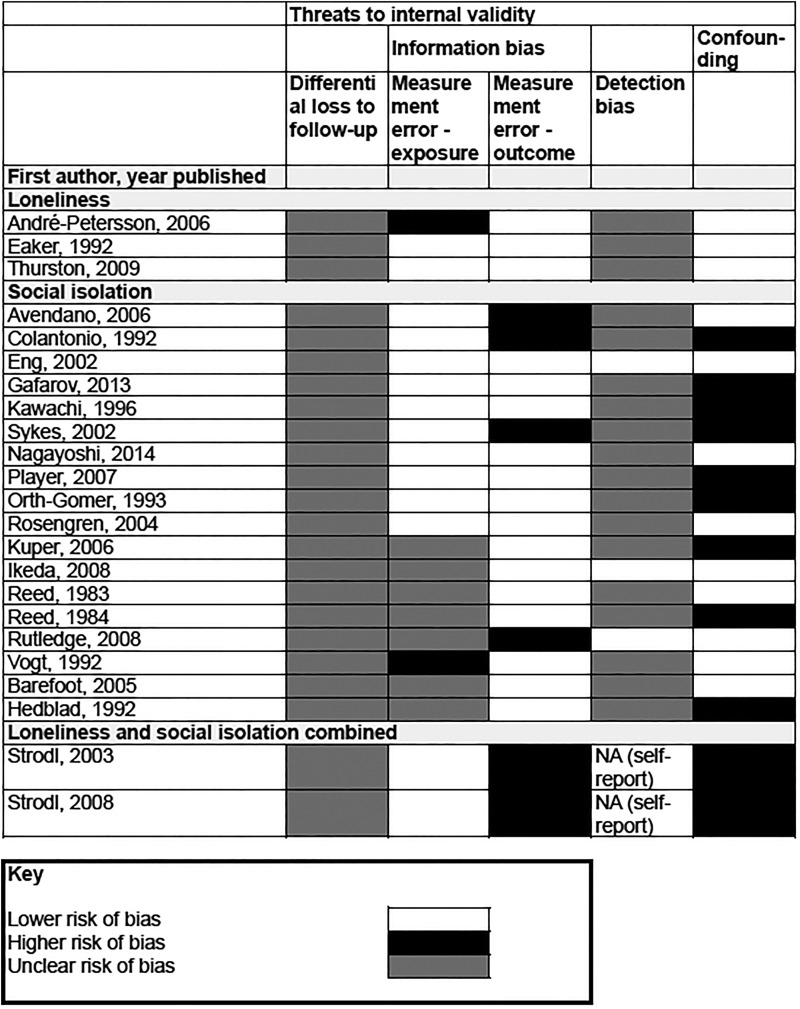

Study validity

Figure 2 summarises risk of bias across the studies included in our review (see online supplementary appendix 3 for details of criteria). For many of the instruments assessing social relationships, information on reliability and validity was limited (online supplementary appendix 4 displays detailed information on the validity and reliability of tools). Four cohorts (six articles) relied on subjects reporting new diagnosis for all or part of the outcomes measured, and were judged to be at greater risk of misclassification (see online supplementary appendix 2 for details of outcome assessment). Limited information on attrition and blinding of outcome assessment meant that susceptibility to differential loss to follow-up and detection bias was unclear. We note that the multiplicity of risk factors investigated and the differential length of follow-up suggest that outcome assessment is unlikely to have been influenced by knowledge of baseline information on social relationships.

Figure 2.

Internal validity. NA, not applicable.

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix3.pdf (9.5KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix4.pdf (146.2KB, pdf)

The results reported in 12 papers were at lower risk of confounding, that is, analyses controlled or accounted for age, gender and socioeconomic status.21 22 27 28 30 33 36 37 39 40 42 43 Four studies presented results from univariate analyses,31 34 35 41 with a further study adjusting for age only.26 The remaining eight reports did not control for socioeconomic status, although in the case of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study the relative socioeconomic homogeneity of the sample may limit the impact of this omission.22 24

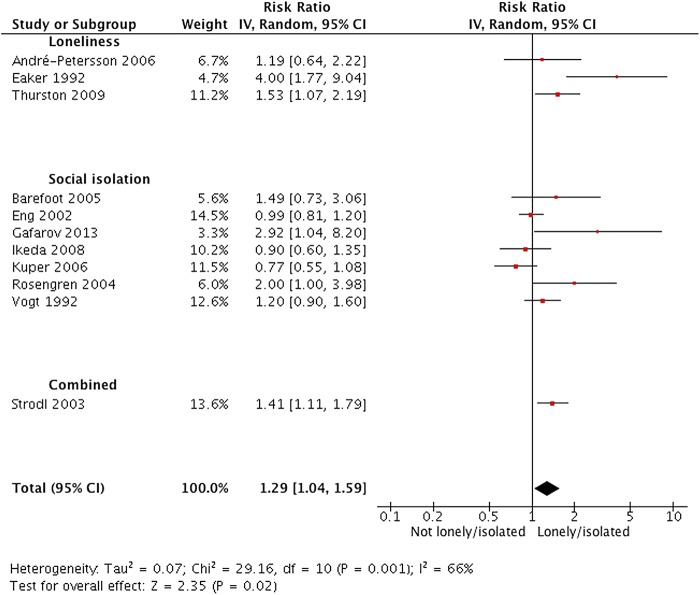

Loneliness, social isolation and CHD

Across 11 studies (3794 events; one study did not report numbers) based on independent samples, the average relative risk of new CHD when comparing high versus low loneliness or social isolation was 1.29 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.59; see figure 3). We found evidence of heterogeneity within this comparison (I2=66%, χ2=29.16, df=10, p=0.001) and explored whether this could be explained by social relationship domain (loneliness vs social isolation), gender, risk of confounding and higher risk of bias due to exposure measurement error. We found no evidence that effects differed according to each subgroup (see online supplementary appendix 5). We were not able to explore other potential sources of heterogeneity due to limited information and study numbers.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of studies investigating incident CHD. CHD, coronary heart disease.

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix5.pdf (131.3KB, pdf)

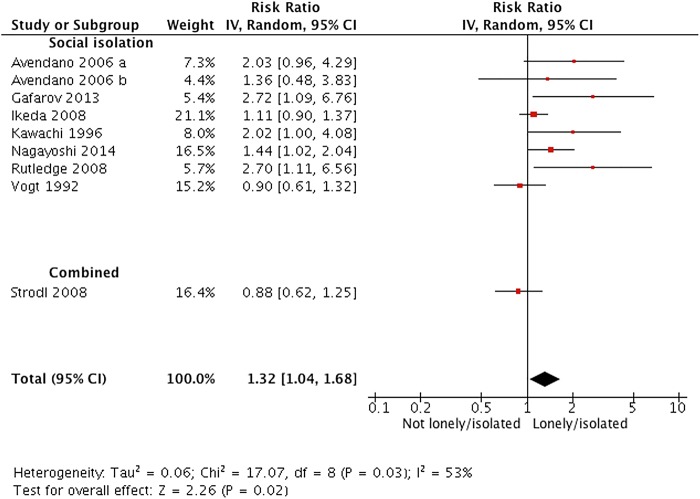

Social isolation and stroke

Across nine independent study samples (2577 events; one study did not report numbers), the average relative risk of stroke incidence was 1.32 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.68; see figure 4). Following confirmation of heterogeneity (I2=53%, χ2=17.07, df=8, P=0.03) we performed subgroup analyses according to risk of confounding and risk of bias due to outcome measurement error (there were too few studies to perform any other analyses). There was no evidence of effects differing according to subgroup (see online supplementary appendix 6); we had insufficient information to explore other potential sources of heterogeneity.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of studies investigating incident stroke.

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix6.pdf (88.1KB, pdf)

Risk of bias across studies

To test whether our findings were sensitive to internal study validity, we compared results with and without studies at greater risk of bias. We found no evidence of a difference in the ratio of the relative risks for CHD and stroke according to study validity (see table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity analyses

| Pooled estimate of the relative risk, based on all studies (95% CI) (number of effect estimates) | Without studies at greater risk of information bias (exposure) | Without studies at greater risk of information bias (outcome) | Without studies at greater risk of confounding | Without studies at greater risk of bias in at least one domain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary heart disease | 1.29 (1.04 to 1.59) (n=11) | 1.34 (1.03 to 1.74) (n=9) | 1.28 (1.01 to 1.63) (n=10) | 1.34 (1.03 to 1.76) (n=7) | 1.42 (1.00 to 2.01) (n=7) |

| Stroke | 1.32 (1.04 to 1.68) (n=8) | 1.42 (1.09 to 1.85) (n=7) | 1.30 (0.98 to 1.71) (n=4) | 1.34 (1.05 to 1.73) (n=6) | 1.30 (0.98 to 1.71) (n=4) |

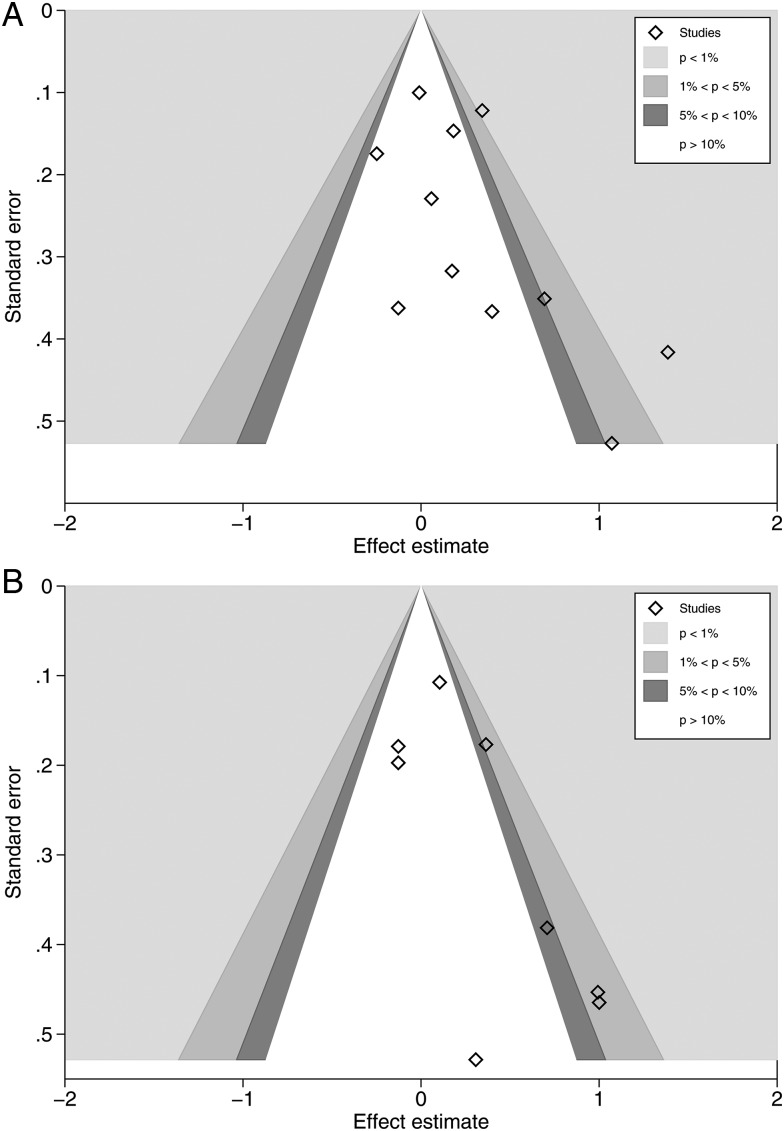

Visual assessment of contour-enhanced funnel plots suggested that studies might be missing in areas of statistical significance (see figure 5A, B). Comparing fixed-effects and random-effects estimates, we found the random-effects estimate to be more beneficial (CHD: relative risk (RR) random-effects: 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.59, compared with RR fixed-effects: 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.31; stroke: RR, random-effects: 1.32, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.68, compared with RR fixed-effects: 1.19, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.36). This suggests the presence of small-study effects, which could be due to reporting bias. Although we found no evidence that study quality and true heterogeneity explained small-study effects in our review, these, along with chance, remain possible explanations.

Figure 5.

(A) Contour-enhanced funnel plot, coronary heart disease studies. (B) Contour-enhanced funnel plot, stroke studies.

Additional studies

Seven papers with a measure of social isolation were excluded from quantitative synthesis since they either did not report data in a format suitable for pooling and/or shared data with other studies.23 25–27 29 38 41 Of the four papers that did not duplicate data from other studies, two reported results based on the Honolulu Heart Program: social isolation appeared to predict CHD but not stroke, in analyses adjusted for age, though the association disappeared in multivariate analysis.26 27 In a univariate analysis of data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (USA) the Lubben Social Network score was not significantly associated with incident CHD among people with prehypertension.41 A further study found no evidence of an association between social isolation and CHD among men in France and Northern Ireland,29 although we note that this study controlled for depression, one of the possible pathways through which social isolation might lead to disease.

Discussion

Summary of findings and comparison with other work

Our review found that poor social relationships were associated with a 29% increase in risk of incident CHD and a 32% increase in risk of stroke. This is the first systematic review to focus on the prospective association between loneliness or social isolation and first occurrence of CHD or stroke.

Earlier reviews reported that cardiovascular disease (CVD) prognosis is worse among people with poorer social relationships.1 2 Narrative reviews on social support and CHD have described an association with prognosis as well as incidence, but the strength of evidence was low.47 48 A recent review of seven papers linked loneliness and social isolation to occurrence of CHD,49 but the effect on prognosis and incidence could not be disentangled.

We found an association between poor social relationships and incident CVD comparable in size to other recognised psychosocial risk factors, such as anxiety50 and job strain.51 Our findings indicate that efforts to reduce the risk of CHD and stroke could benefit from taking both loneliness and social isolation into account, as we found no evidence to suggest that one was more strongly related to disease incidence than the other. This is in line with other research linking subjective and objective isolation to hypertension, a risk factor for both stroke and CHD.8 9

Strengths and limitations

Our focus on longitudinal studies allowed us to comment on the direction of the relationship between social relationships and health, and avoid the problem of reverse causation. Pooling results from studies of CHD that measured loneliness and isolation allowed us to answer the broader question of whether deficiencies in social relationships are associated with disease incidence. We anticipated and explored heterogeneity where possible but found no statistical evidence that components of internal validity were associated with effect estimates.

Subgroup analyses specified a priori showed no difference between the association of loneliness or social isolation with CHD incidence, and we found no evidence across studies of differences between men and women. We found insufficient data to explore the relative effects of the quantity and quality of relationships, or study effect modifiers in depth. Seven of the estimates included in our meta-analyses (five CHD, two stroke) were extracted from studies where participants were of higher socioeconomic status and in better health than the target population. The role of deficiencies in social relationships may be greater among individuals under stress,52 and our results may underestimate the health-damaging implications of loneliness and social isolation among disadvantaged groups. Our review included some data collected from 1965; more recent strategies for CHD prevention may have modified the influence of loneliness and social isolation on disease incidence.

In common with other reviews of observational studies, we cannot infer causality from our findings, nor can we exclude confounding by unmeasured common causes, or reverse causation if deficiencies in social relationships are the result of subclinical disease. Publication bias is a concern in every review, and may lead us to overestimate the ‘true’ effect of poor social relationships. Conversely, our pooled effects could be a conservative estimate: most of the studies in this review statistically adjusted for factors that are likely to be on the causal pathway, such as depression or health-related behaviour.

Implications

The main finding of our review, that isolated individuals are at increased risk of developing CHD and stroke, supports public health concerns over the implications of social relationships for health and well-being. Our work suggests that addressing loneliness and social isolation may have an important role in the prevention of two of the leading causes of morbidity in high-income countries.

A variety of interventions directed at loneliness and social isolation have been developed, ranging from group initiatives such as educational programmes and social activities, to one-to-one approaches including befriending and cognitive-behavioural therapy. These have primarily focused on secondary prevention, targeting people identified as isolated or lonely, but their effectiveness is unclear. Evaluative research is needed to investigate their impact on a range of health outcomes. Addressing health-damaging behaviours is also likely to be important, with lonely and isolated people more likely to smoke and be physically inactive, for example5 primary prevention strategies, such as promoting social networks or developing resilience, have received limited attention to date. Risk factors for loneliness and social isolation such as gender, socioeconomic position, bereavement and health status are well established14 18 and hold the key to identifying people who may benefit from intervention.

Our findings suggest that tackling loneliness and isolation may be a valuable addition to CHD and stroke prevention strategies. Health practitioners have an important role to play in acknowledging the importance of social relations to their patients.53 54

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

People with poorer social relationships are at increased risk of premature death. The implications of social relationships for disease onset are unclear.

What might this study add?

This systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies found that deficiencies in social relationships are associated with an increased risk of developing coronary heart disease and stroke of around 30%. This association is comparable in size to other recognised psychosocial risk factors, such as anxiety and job strain.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Efforts to reduce cardiovascular disease incidence need to consider loneliness and social isolation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rocio Rodriguez-Lopez and Melissa Harden for carrying out the electronic literature searches, and Martin Bland and Dan Pope for their advice on meta-analysis software and data analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: NKV and BH developed the idea for the article. NKV developed a protocol under the supervision of SG, BH and MK. SR assisted with data acquisition and extraction. NKV wrote the first draft, with all authors contributing to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. NKV is the guarantor.

Funding: Department of Health, National Institute for Health Research, Research Trainees Coordinating Centre (DRF-2013-06-074).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10:227–37. 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkman LF, Glass TA. Social network epidemiology. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014:234–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:218–27. 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, et al. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol 2011;30:377–85. 10.1037/a0022826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, et al. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004;29:593–611. 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAvay GJ, Seeman TE, Rodin J. A longitudinal study of change in domain-specific self-efficacy among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1996;51:P243–53. 10.1093/geronb/51B.5.P243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant N, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Social isolation and stress-related cardiovascular, lipid, and cortisol responses. Ann Behav Med 2009;37:29–37. 10.1007/s12160-009-9081-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Masi CM, et al. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol Aging 2010;25:132–41. 10.1037/a0017805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Global health estimates summary tables: DALYs by cause, age and sex, by World Bank income group. 2013. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/ (accessed 26 June 2015).

- 11.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York, UK: University of York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.PROSPERO. Loneliness and social isolation as determinants of health: a systematic review of longitudinal observational studies set in high-income countries. 2014. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ (accessed 22Jul 2015).

- 13.Perlman D, Peplau AL. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In: Duck S, Gilmour R. Personal relationships in disorder. London: Academic Press, 1981:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg TG, Dykstra PA. Loneliness and social isolation. In: Vangelisti A, Perlman D. Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006:485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Bank. World Bank list of economies. 2014. siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/CLASS.XLS (accessed 29 May 2015).

- 16.Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, et al. Assessing risk of bias and confounding in observational studies of interventions or exposures: further development of the RTI item bank. Rockville MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stringhini S, Berkman L, Dugravot A, et al. Socioeconomic status, structural and functional measures of social support, and mortality: the British Whitehall II Cohort Study, 1985–2009. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175:1275–83. 10.1093/aje/kwr461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinquart M, Sörensen S, Shohov S. Risk factors for loneliness in adulthood and old age: a meta-analysis. Adv Psych Res 2003;19:111–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1690–1. 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 21.André-Petersson L, Hedblad B, Janzon L, et al. Social support and behavior in a stressful situation in relation to myocardial infarction and mortality: who is at risk? Results from prospective cohort study “Men born in 1914,” Malmo, Sweden. Int J Behav Med 2006;13:340–7. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1304_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eng PM, Rimm EB, Fitzmaurice G, et al. Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:700–9. 10.1093/aje/155.8.700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedblad B, Ostergren PO, Hanson BS, et al. Influence of social support on cardiac event rate in men with ischaemic type ST segment depression during ambulatory 24-h long-term ECG recording. Eur Heart J 1992;13:433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996;50:245–51. 10.1136/jech.50.3.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orth-Gomér K, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosom Med 1993;55:37–43. 10.1097/00006842-199301000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed D, McGee D, Yano K. Psychosocial processes and general susceptibility to chronic disease. Am J Epidemiol 1984;119:356–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed D, McGee D, Yano K, et al. Social networks and coronary heart disease among Japanese men in Hawaii. Am J Epidemiol 1983;117:384–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L, Orth-Gomér K. Coronary disease in relation to social support and social class in Swedish men. A 15 year follow-up in the study of men born in 1933. Eur Heart J 2004;25:56–63. 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sykes D, Arveiler D, Salters CP, et al. Psychosocial risk factors for heart disease in France and Northern Ireland: the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME). Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1227–34. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eaker ED, Pinsky J, Castelli WP. Myocardial infarction and coronary death among women: psychosocial predictors from a 20-year follow-up of women in the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:854–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gafarov VV, Panov DO, Gromova EA, et al. The influence of social support on risk of acute cardiovascular diseases in female population aged 25–64 in Russia. Int J Circumpolar Health 2013;72 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuper H, Adami HO, Theorell T, et al. Psychosocial determinants of coronary heart disease in middle-aged women: a prospective study in Sweden. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:349–57. 10.1093/aje/kwj212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutledge T, Linke SE, Olson MB, et al. Social networks and incident stroke among women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Psychosom Med 2008;70:282–7. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181656e09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strodl E, Kenardy J. The 5-item mental health index predicts the initial diagnosis of nonfatal stroke in older women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:979–86. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strodl E, Kenardy J, Aroney C. Perceived stress as a predictor of the self-reported new diagnosis of symptomatic CHD in older women. Int J Behav Med 2003;10:205–20. 10.1207/S15327558IJBM1003_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avendano M, Kawachi I, Van Lenthe F, et al. Socioeconomic status and stroke incidence in the US elderly: the role of risk factors in the EPESE study. Stroke 2006;37:1368–73. 10.1161/01.STR.0000221702.75002.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barefoot JC, Grønbaek M, Jensen G, et al. Social network diversity and risks of ischemic heart disease and total mortality: findings from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:960–7. 10.1093/aje/kwi128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colantonio A, Kasi SV, Ostfeld AM. Depressive symptoms and other psychosocial factors as predictors of stroke in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136: 884–94. 10.1093/aje/136.7.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikeda A, Iso H, Kawachi I, et al. Social support and stroke and coronary heart disease: the JPHC study cohorts II. Stroke 2008;39:768–75. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagayoshi M, Everson-Rose SA, Iso H, et al. Social network, social support, and the risk of incident stroke: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation 2014;129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Player MS, King DE, Mainous AG III, et al. Psychosocial factors and progression from prehypertension to hypertension or coronary heart disease. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:403–11. 10.1370/afm.738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 2009;71:836–42. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogt TM, Mullooly JP, Ernst D, et al. Social networks as predictors of ischemic heart disease, cancer, stroke and hypertension: incidence, survival and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:659–66. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90138-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berkman L, Breslow L. Health and ways of living: the alameda county study. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lubben J. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Community Health 1988;11:42–52. 10.1097/00003727-198811000-00008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodger B, Byles JE, Higganbotham N. Assessment of a short scale to measure social support among older people. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23: 260–5. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuper H, Marmot M, Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med 2002;2:267–314. 10.1055/s-2002-35401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2010;72:229–38. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update on current knowledge. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:337–54. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, et al. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:38–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fransson EI, Nyberg ST, Heikkilä K, et al. Job strain and the risk of stroke: an individual-participant data meta-analysis. Stroke 2015;46:557–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen S, Gottlieb B, Underwood L. Social relationships and health. In: Cohen S, Underwood L, Gottlieb B. Measuring and Intervening in Social Support. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000:3–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix1.pdf (99.3KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix2.pdf (136.3KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix3.pdf (9.5KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix4.pdf (146.2KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix5.pdf (131.3KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2015-308790supp_appendix6.pdf (88.1KB, pdf)