Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of etanercept (ETN) after 48 weeks in patients with early active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA).

Methods

Patients meeting Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification criteria for axSpA, but not modified New York radiographic criteria, received double-blind ETN 50 mg/week or placebo (PBO) for 12 weeks, then open-label ETN (ETN/ETN or PBO/ETN). Clinical, health, productivity, MRI and safety outcomes were assessed and the 48-week data are presented here.

Results

208/225 patients (92%) entered the open-label phase at week 12 (ETN, n=102; PBO, n=106). The percentage of patients achieving ASAS40 increased from 33% to 52% between weeks 12 and 48 for ETN/ETN and from 15% to 53% for PBO/ETN (within-group p value <0.001 for both). For ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN, the EuroQol 5 Dimensions utility score improved by 0.14 and 0.08, respectively, between baseline and week 12 and by 0.23 and 0.22 between baseline and week 48. Between weeks 12 and 48, MRI Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada sacroiliac joint (SIJ) scores decreased by −1.1 for ETN/ETN and by −3.0 for PBO/ETN, p<0.001 for both. Decreases in MRI SIJ inflammation and C-reactive protein correlated with several clinical outcomes at weeks 12 and 48.

Conclusions

Patients with early active nr-axSpA demonstrated improvement from week 12 in clinical, health, productivity and MRI outcomes that was sustained to 48 weeks.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Spondyloarthritis, Anti-TNF

Introduction

MRI to detect inflammation before the development of X-ray changes is an important tool for diagnosing spondyloarthritis (SpA).1–5 The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) have created a classification system for axial SpA (axSpA) based on whether patients meet clinical criteria or imaging criteria.6 7 Patients meeting ASAS criteria for axSpA without sacroiliitis on X-ray examination are classified as having non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA). In several recent studies, anti-tumour necrosis factor agents, including etanercept (ETN), demonstrated efficacy in patients with nr-axSpA.8–15 However, additional long-term data are needed.

In the first period of an ongoing, randomised, placebo-controlled study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01258738), patients with early nr-axSpA unresponsive to two or more non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) experienced significant improvement in clinical signs and symptoms and MRI-measured inflammation after 12 weeks of double-blind treatment with ETN; clinical improvement continued for the next 12 weeks of the open-label period.14 This report provides clinical, health, productivity, MRI and safety data to week 48 and evaluates whether (1) treatment response improves between 12 and 24 weeks; (2) treatment response is sustained over 48 weeks; (3) decreases in MRI scores continue between weeks 12 and 48; (4) a correlation exists between MRI changes and conventional efficacy outcomes.

Patients and methods

Patients

Details of the study design were published previously.14 Patients were aged 18–49 years; met ASAS axSpA criteria; had symptom duration >3 months and <5 years and a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score >4; and treatment with two or more NSAIDs had failed. Patients were excluded if they met the modified New York criteria for radiographic axSpA confirmed by central reading.16 MRI was obtained during screening to look for sacroiliac joint (SIJ) inflammation; all patients met the ASAS imaging criteria (sacroiliitis on imaging and one or more SpA features) or clinical criteria (human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 positive and two or more other SpA features). Patients were stratified by positive or negative sacroiliitis and geographical region.

Study design

This ongoing phase IIIb, 104-week clinical study consists of a 12-week randomised, double-blind period in which patients received 50 mg ETN subcutaneously once a week or placebo (PBO), then a 92-week open-label phase in which all patients received 50 mg ETN weekly. All patients continued background NSAID treatment. Clinical assessments at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 40 and 48 included: ASAS20, ASAS40,17 ASAS5/6, ASAS partial remission, BASDAI50 and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score inactive disease (ASDAS<1.3).7 Assessments were added for continuous ASDAS based on C-reactive protein (CRP), BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) and total back pain.7 CRP measurements were performed centrally using a high-sensitivity assay. Patients were also assessed using MRI of the SIJ and spine. Scoring methods included Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC)18 19 SIJ and spine 6-discovertebral units; and Ankylosing Spondylitis spine MRI-activity (ASspiMRI-a)20 at baseline, weeks 12 and 48. Additionally, patient-reported health-related quality-of-life assessments were administered, including the EuroQol 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)21 and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) physical and mental components.22 SF-36 was assessed at baseline and weeks 4, 12, 24 and 48; EQ-5D additionally at weeks 8, 16 and 40.

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire was also collected.23 This questionnaire concerns the effect of the specified health problem on work absence and productivity and regular activities. It includes several subscale scores; overall work impairment is presented. Scores range from 0 to 100; higher numbers indicate greater impairment and less productivity. WPAI was collected at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 40 and 48.

MRI

All study MRIs were performed locally, collected and then read centrally. The first MRI was performed during screening, after the SIJ X-ray report from the central reader had been reviewed by the investigator. The X-ray result was required to be negative for radiological sacroiliitis grades 3–4 unilaterally or grade ≥2 bilaterally, defined by the modified New York criteria for radiographic axSpA. The screening MRI was assessed by a central reader to determine whether it was positive for sacroiliitis according to ASAS criteria. This MRI was also included with MRI scans obtained at 12 and 48 weeks in reading exercises by central readers who scored the scans for the degree of SIJ and spinal inflammation.

Two independent readers scored the screening, 12- and 48-week MRI scans, which were assessed simultaneously, blinded to time point, treatment and patient characteristics. A third reader assessed MRI scans with discrepant scores according to prespecified adjudication rules. Results requiring adjudication were identified after the two independent reviews were completed. Adjudication was required for those cases in which one reader considered the MRI results to be unreadable, or if the scores moved in different directions (one positive, one negative) and differed by >5 points for ASspiMRI-a or SPARCC spinal and by >3 points for SPARCC SIJ.

In a post hoc completer analysis, structural lesions at baseline and week 48 were scored using the SPARCC MRI SIJ structural score (SSS), assessing fat metaplasia, erosion, backfill and ankylosis on T1-weighted spin echo MRI and assigning a yes/no score according to the presence/absence of lesions in SIJ quadrants (fat metaplasia, erosion) or SIJ halves (backfill, ankylosis).24 Five consecutive semicoronal slices were assessed by scrolling anteriorly from the transitional slice, the first cartilaginous slice that visualises the ligamentous joint when viewed anteriorly to posteriorly. Fat and erosion were each assigned a 0–8 score per slice for five slices, for a scoring range of 0–40. Backfill and ankylosis were each assigned a 0–4 score per slice for five slices, for a scoring range of 0–20.

Statistical methods

Analyses of clinical and imaging efficacy used the open-label modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population, consisting of all patients in the double-blind mITT population who took one or more doses of the study drug and had one or more visits during the open-label period. Clinical efficacy and MRI analyses used the mITT, last observation carried forward population, and the health and productivity outcomes analyses used the mITT, observed case (OC) population. Between-group p values at 12 weeks for clinical, health and productivity outcomes were determined using analysis of covariance models. Paired t tests were used to compare within-group differences between baseline and 48 weeks and other time points for the clinical, health outcomes and MRI scores. Within-group differences between weeks 12 and 48 and weeks 24 and 48 for the ETN/ETN group, OC population, were examined using paired t tests for ASDAS, BASDAI, BASMI, BASFI, CRP and total back pain post hoc and were determined using McNemar's test for ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS inactive disease and BASDAI50 post hoc. Two 48-week efficacy endpoints were added that were not in the study protocol: ASDAS clinically important improvement and ASDAS major improvement.25

Spearman correlations (R) were used to evaluate the correlation between change from baseline for SPARCC MRI SIJ score as well as CRP and change from baseline for ASDAS, BASDAI, BASMI, BASFI and total back pain (OC population) and fat metaplasia, erosion, backfill and ankylosis (48-week completers), post hoc.

The open-label safety population included all patients who completed the double-blind period and took one or more doses of the study drug during the open-label period.

Results

Patients

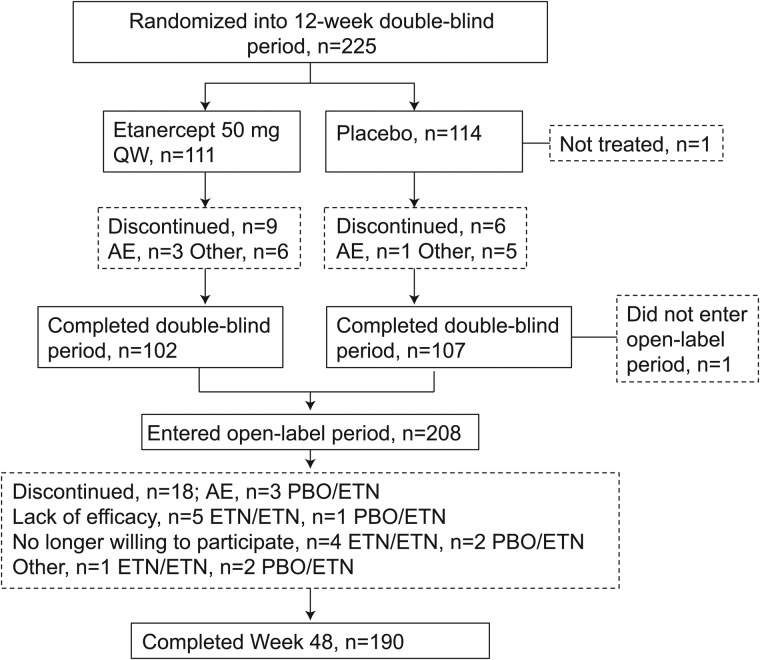

Of the 215 patients comprising the double-blind mITT population, 208 patients entered the open-label period (ETN/ETN, n=102; PBO/ETN, n=106) and 190 patients completed 48 weeks (ETN/ETN, n=92; PBO/ETN, n=98; figure 1). The mITT population for the open-label period included 205 patients (ETN/ETN, n=100; PBO/ETN, n=105). For the open-label safety population, baseline mean (SD) age was 32 (7.8) years, 61% were male, 74% were white and mean duration of disease symptoms was 2.5 (1.9) years (table 1). Mean CRP was 6.7 (10.7) and 148/208 (71.2%) patients were HLA-B27 positive. BASDAI was 6.0 (1.8), indicating that patients had moderate to severe disease. Most patients (169/208, 81%) met ASAS imaging criteria; 39/208 (19%) patients did not meet imaging criteria but met ASAS clinical criteria and 54% of patients met both.6

Figure 1.

Patient disposition, full analysis population. AE, adverse event; ETN, etanercept; PBO, placebo; QW, once weekly.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients entering the open-label period

| ETN/ETN (n=102) | PBO/ETN (n=106) | Combined (n=208) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 31.6 (7.8) | 32.1 (7.7) | 31.9 (7.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 65 (63.7) | 61 (57.5) | 126 (60.6) |

| White, n (%) | 77 (75.5) | 77 (72.6) | 154 (74.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.6 (5.0) | 24.6 (4.1) | 25.1 (4.6) |

| Duration of disease symptoms, years | 2.4 (2.0) | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.9) |

| HLA-B27 positive, n (%) | 68 (66.7) | 80 (75.5) | 148 (71.2) |

| CRP, mg/L | 7.0 (10.7) | 6.4 (10.6) | 6.7 (10.7) |

| Elevated CRP (>3 mg/L), n (%) | 48 (47.1) | 42 (39.6) | 90 (43.3) |

| BASDAI, 0–10 cm VAS | 6.0 (1.8) | 6.0 (1.9) | 6.0 (1.8) |

| BASFI, 0–10 cm VAS | 4.2 (2.4) | 3.8 (2.5) | 4.0 (2.4) |

| BASMI, 0–10 cm VAS | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.3) |

| Total back pain, 0–10 cm VAS | 5.5 (2.4) | 5.4 (2.4) | 5.5 (2.4) |

| PGA, 0–10 cm VAS | 5.7 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.9) | 5.4 (1.9) |

| PtGA, 0–10 cm VAS | 5.8 (2.2) | 5.8 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.2) |

| ASDAS-CRP | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.0) |

| EQ-5D utility score, range 0–1 | 0.52 (0.33) | 0.59 (0.28) | 0.56 (0.31) |

| SF-36 MCS, range 0–100 | 42.3 (11.9) | 43.5 (11.1) | 42.9 (11.5) |

| SF-36 PCS, range 0–100 | 37.7 (8.6) | 37.4 (8.3) | 37.5 (8.4) |

| WPAI overall, range 0–100* | 45.0 (26.2) | 43.9 (27.8) | 44.5 (26.9) |

| MRI sacroiliitis positive by ASAS criteria, n (%) | 84 (82.4) | 85 (80.2) | 169 (81.3) |

| SPARCC MRI SIJ score, range 0–72 | 7.9 (10.9) | 7.0 (11.0) | 7.4 (10.9) |

| SPARCC MRI 6-DVU spinal score, range 0–108 | 7.6 (11.4) | 6.9 (9.2) | 7.2 (10.3) |

| ASspiMRI-a score, range 0–138 | 1.6 (2.5) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.5 (2.1) |

*ETN/ETN, n=58; PBO/ETN, n=58.

Open-label safety population, except BASMI, SF-36 MCS, WPAI overall, SPARCC MRI SIJ, SPARCC MRI spinal, ASspiMRI-a, which are mITT from the double-blind period (ETN/ETN, n=106; PBO/ETN, n=109).

Values are shown as mean (SD) unless stated otherwise.

ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASDAS-CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein; ASspiMRI-a, Ankylosing Spondylitis spine MRI-activity; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DVU, discovertebral units; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 Dimensions; ETN, etanercept; HLA-B27, human leucocyte antigen B27; MCS, mental component summary; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; PBO, placebo; PCS, physical component summary; PGA, physician global assessment; PtGA, patient global assessment; SF-36, 36-item Short Form Health Survey; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; SPARCC, Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada; VAS, visual analogue scale; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire.

Clinical efficacy

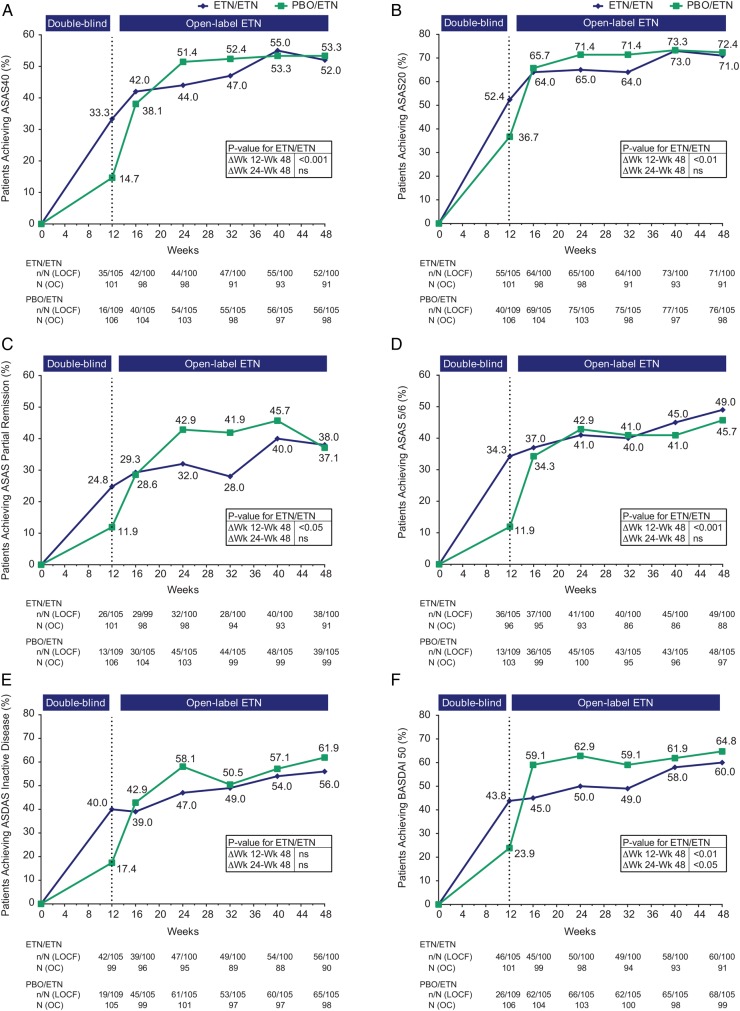

By week 48, 108/205 (53%) patients achieved ASAS40, 52% and 53% in the ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN groups, respectively (figure 2A). Between weeks 12 and 48, the percentage of patients achieving ASAS20, ASAS 5/6, ASDAS inactive disease and BASDAI50 increased for the two treatment groups and both groups achieved similar results at week 48 (figures 2B–F). Improvement in ASDAS and BASDAI continued between weeks 12 and 48 for both groups (table 2). Mean (SD) values are provided in online supplementary table S1. At 48 weeks, ASDAS clinically important improvement was achieved by 64/100 (64%) and 68/105 (65%) patients receiving ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN, respectively; ASDAS major improvement was achieved by 37/100 (37%) and 35/105 (33%) patients. For ETN/ETN, function, measured by BASFI, improved significantly between weeks 12 and 48, p<0.001; change in mobility measured by BASMI was not statistically significant (table 2). CRP decreased between weeks 12 and 48, from a mean (SEM) of 3.0 (0.6) to 2.2 (0.5) for ETN/ETN, p=NS; and from 6.0 (1.0) to 1.7 (0.2) for PBO/ETN, p<0.001.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients achieving (A) ASAS40 response, (B) ASAS20 response, (C) ASAS partial remission, (D) ASAS 5/6, (E) ASDAS inactive disease and (F) BASDAI50. Population is modified intention-to-treat (mITT), last observation carried forward (LOCF). The actual number of patients, observed case (OC), is also shown. p Values for differences in results between weeks 12 and 48 and between weeks 24 and week 48 for the ETN/ETN group are from McNemar’s test, OC data. ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; ETN, etanercept; ns, non-significant; PBO, placebo; Δ, change.

Table 2.

Mean (SEM) change from baseline for clinical efficacy and patient-reported outcomes

| Double-blind phase | Open-label phase | p Values† | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 | Week 12 p Value* |

Week 16 | Week 24 | Week 32 | Week 40 | Week 48 | Week 12– week 48 | Week 24– week 48 | ||

| N=Pts in study | ETN/ETN | N=101 | N=99 | N=98 | N=94 | N=93 | N=91 | |||

| PBO/ETN | N=106 | N=104 | N=103 | N=100 | N=99 | N=99 | ||||

| ASDAS-CRP | ETN/ETN | −1.1 (0.1) | <0.001 | −1.4 (0.1) | −1.5 (0.1) | −1.4 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| PBO/ETN | −0.5 (0.1) | −1.4 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −1.5 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | −1.6 (0.1) | ||||

| BASDAI | ETN/ETN | −2.0 (0.3) | <0.05 | −2.7 (0.2) | −2.9 (0.2) | −2.7 (0.2) | −3.2 (0.2) | −3.2 (0.2) | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| PBO/ETN | −1.3 (0.3) | −3.0 (0.2) | −3.3 (0.2) | −3.2 (0.2) | −3.4 (0.2) | −3.5 (0.2) | ||||

| BASFI | ETN/ETN | −1.4 (0.2) | <0.05 | −1.8 (0.2) | −1.9 (0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) | −2.2 (0.2) | −2.2 (0.2) | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| PBO/ETN | −0.8 (0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) | −1.9 (0.2) | −2.0 (0.2) | −2.1 (0.2) | −2.1 (0.2) | ||||

| BASMI | ETN/ETN | −0.3 (0.2) | NS | −0.4 (0.1) | −0.5 (0.1) | −0.6 (0.1) | −0.5 (0.1) | −0.5 (0.1) | NS | NS |

| PBO/ETN | −0.3 (0.1) | −0.4 (0.1) | −0.3 (0.1) | −0.5 (0.1) | −0.5 (0.1) | −0.4 (0.1) | ||||

| Total back pain | ETN/ETN | −2.0 (0.3) | <0.01 | −2.7 (0.3) | −2.8 (0.3) | −2.6 (0.3) | −3.3 (0.3) | −3.1 (0.3) | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| PBO/ETN | −1.1 (0.3) | −2.6 (0.3) | −2.9 (0.2) | −2.9 (0.3) | −3.2 (0.2) | −3.2 (0.3) | ||||

| SF-36 PCS | ETN/ETN | 6.2 (1.0) | <0.05 | NA | 6.7 (0.9) | NA | NA | 8.0 (1.0) | <0.05 | NS |

| PBO/ETN | 3.8 (0.9) | NA | 7.3 (0.8) | NA | NA | 8.5 (0.9) | ||||

| SF-36 MCS | ETN/ETN | 2.4 (1.3) | NS | NA | 3.5 (1.3) | NA | NA | 3.5 (1.2) | NS | NS |

| PBO/ETN | 1.6 (1.2) | NA | 4.4 (1.0) | NA | NA | 3.5 (1.1) | ||||

| EQ-5D utility score | ETN/ETN | 0.14 (0.04) | NS | 0.19 (0.04) | 0.21 (0.03) | NA | 0.24 (0.04) | 0.23 (0.03) | NS | NS |

| PBO/ETN | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.20 (0.03) | NA | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.22 (0.03) | ||||

| N=Pts with work data | ETN/ETN | N=48 | N=49 | N=45 | N=46 | N=45 | N=45 | |||

| PBO/ETN | N=50 | N=46 | N=43 | N=43 | N=47 | N=45 | ||||

| WPAI overall | ETN/ETN | −20.8 (4.9) | NS | −16.3 (3.8) | −14.9 (4.5) | −17.6 (3.8) | −23.7 (4.2) | −23.0 (3.6) | <0.05 | NS |

| PBO/ETN | −12.1 (4.9) | −16.4 (2.9) | −18.6 (3.7) | −16.5 (3.3) | −20.5 (3.0) | −17.5 (3.9) | ||||

*Analysis of covariance model used for between-group p values.

†Paired t test used for within-group response difference for ETN/ETN.

Analyses performed on mITT, LOCF population for ASDAS-CRP, BASDAI, BASFI, BASMI, total back pain; mITT, observed case population for SF-36 PCS, SF-36 MCS, EQ-5D utility score, WPAI overall.

ASDAS-CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 Dimensions; ETN, etanercept; LOCF, last observation carried forward; MCS, mental component summary; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; NA, not available, NS, non-significant; PCS, physical component summary; PBO, placebo; Pts, patients; SEM, SE of the mean; SF-36, 36-item Short Form Health Survey; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire.

In a post hoc analysis, within-group improvement between weeks 12 and 48 for ETN/ETN was significant for ASDAS, BASDAI and BASFI (p<0.001 for all) and total back pain (p<0.01); BASMI was not significant (table 2). Between weeks 24 and 48, within-group improvement was significant at p<0.01 for BASFI, p<0.05 for ASDAS, BASDAI and total back pain; BASMI was not significant.

For the ETN/ETN group, a significantly greater proportion of patients at 48 weeks than 12 weeks achieved ASAS40 and ASAS 5/6 (p<0.001), ASAS20 and BASDAI50 (p<0.01) and ASAS partial remission (p<0.05); ASDAS inactive disease was not significant (figure 2A–F). Between weeks 24 and 48, within-group improvement was significant only for BASDAI50 (p<0.05). Thus, for efficacy outcomes, the greatest clinical improvement for ETN/ETN was between weeks 12 and 24.

Patient-reported outcomes

Between baseline and 12 weeks, there was significantly greater improvement with ETN than PBO in the SF-36 physical component score (PCS), p<0.05; differences in the EQ-5D utility score, SF-36 mental component score (MCS) and WPAI overall were not statistically significant (table 2). Between weeks 12 and 48, the EQ-5D utility score, SF-36 PCS and MCS and WPAI overall continued to improve for both treatment groups (table 2).

Within-group response difference for ETN/ETN between weeks 12 and 48 was significant at p<0.05 for SF-36 PCS and WPAI overall; SF-36 MCS and EQ-5D utility score were not significant (table 2). Between weeks 24 and 48, within-group response difference was not significant for any patient-reported outcomes. Overall, for patient-reported outcomes, improvement continued between weeks 12 and 48, but was not statistically significant between weeks 24 and 48.

MRI results

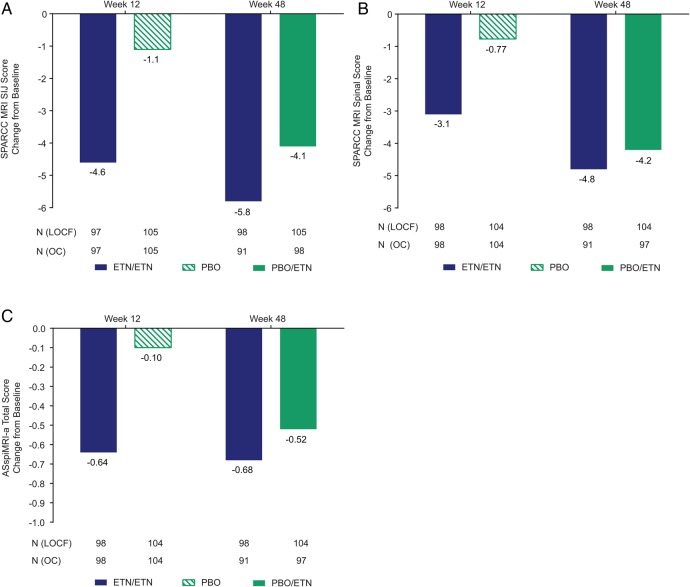

Between baseline and 12 weeks, the decrease in MRI scores differed significantly between ETN and PBO.14 SPARCC SIJ and spinal MRI scores continued improving to week 48 for the ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN groups (figure 3A, B). Mean (SD) changes in SPARCC SIJ MRI scores between baseline and week 48 were −5.8 (10.3) and −4.1 (8.3) for ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN, respectively and were −1.1 (2.9) and −3.0 (7.5) between weeks 12 and 48. Mean (SD) changes in SPARCC spinal MRI scores were −4.8 (11.3) and −4.2 (7.6) for ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN, respectively, between baseline and week 48. The within-group p value for change from baseline to week 48 and week 12 to week 48 was <0.001 for all.

Figure 3.

Mean change from baseline for (A) SPARCC MRI SIJ score, (B) SPARCC MRI spinal score and (C) ASspiMRI-a total score. Population is mITT, LOCF within each study period. The actual number of patients, observed case (OC), is also shown. Mean (SD) baseline values: (A) 7.9 (10.9) for ETN/ETN and 7.0 (11.0) for PBO/ETN; (B) 7.6 (11.4) for ETN/ETN and 6.9 (9.2) for PBO/ETN; (C) 1.6 (2.5) for ETN/ETN and 1.4 (1.7) for PBO/ETN. Changes in score between weeks 12 and 48: (A) −1.1 (2.9) for ETN/ETN and −3.0 (7.5) for PBO/ETN; (B) −1.9 (4.7) for ETN/ETN and −3.6 (5.9) for PBO/ETN; (C) −0.06 (0.68) for ETN/ETN and −0.46 (1.15) for PBO/ETN. Within-group p value between baseline and week 48 from paired t test: <0.001 for all, except ASspiMRI-a total score for ETN/ETN: p<0.01. Within-group p value between week 12 and week 48 from paired t test: <0.001 for all, except ASspiMRI-a total score for ETN/ETN which was non-significant. ASspiMRI-a, Ankylosing Spondylitis spine MRI-activity; ETN, etanercept; LOCF, last observation carried forward; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; PBO, placebo; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; SPARCC, Spondylitis Research Consortium of Canada.

Mean (SD) changes in ASspiMRI-a scores were −0.68 (2.25) and −0.52 (1.38) for ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN, respectively, between baseline and week 48 (figure 3C). Within-group p values for change were <0.01 for ETN/ETN and <0.001 for PBO/ETN between baseline and 48 weeks; change between weeks 12 and 48 was non-significant for ETN/ETN and was significant for PBO/ETN (p<0.001). Online supplementary figure S1 provides mean SPARCC SIJ and spinal MRI scores and ASspiMRI-a scores.

Between baseline and 48 weeks, SSS scores for fat metaplasia, backfill and ankylosis increased by a mean (95% CI) of 0.46 (0.15 to 0.77), 0.89 (0.59 to 1.19) and 0.04 (0 to 0.09), respectively and erosion score decreased by −1.29 (−1.65 to −0.92) for the combined ETN/ETN and PBO/ETN group (see online supplementary figure S2).

Analysis of correlation between MRI and clinical outcomes

Decreases in SPARCC SIJ score from baseline correlated with changes in several clinical measurements and structural lesions in the ETN/ETN group (table 3). At week 12, the score decrease correlated weakly with improvement in ASDAS, BASDAI, total back pain, CRP and ASAS40 (R ranged from 0.27 to 0.35). By week 48, correlations with improvement in ASDAS, BASDAI and total back pain were moderate (R ranged from 0.42 to 0.58, p<0.001) and a weak correlation with BASFI emerged. From baseline to week 48, reduction in SPARCC SIJ inflammation score correlated significantly with development of new fat metaplasia and backfill (R=−0.28, p<0.01 and R=−0.61, p<0.001, respectively). Reduction in SPARCC SIJ inflammation score also correlated significantly with reduction in erosion score (R=0.57, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Correlation between change from baseline in SPARCC SIJ score or CRP and change in clinical and SPARCC SSS measures, ETN/ETN group

| Δ SPARCC SIJ | Δ CRP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | R | N | R | ||

| ASDAS | Week 12 Δ | 94 | 0.35† | 98 | 0.61† |

| Week 48 Δ | 88 | 0.58† | 89 | 0.58† | |

| BASDAI | Week 12 Δ | 97 | 0.27* | 100 | 0.22‡ |

| Week 48 Δ | 90 | 0.42† | 90 | 0.30* | |

| BASMI | Week 12 Δ | 94 | 0.07 | 97 | 0.34† |

| Week 48 Δ | 88 | 0.14 | 88 | 0.28* | |

| BASFI | Week 12 Δ | 97 | 0.17 | 100 | 0.20‡ |

| Week 48 Δ | 90 | 0.35† | 90 | 0.20 | |

| Total back pain | Week 12 Δ | 97 | 0.28* | 100 | 0.20‡ |

| Week 48 Δ | 90 | 0.45† | 90 | 0.20 | |

| CRP | Week 12 Δ | 96 | 0.31* | ||

| Week 48 Δ | 89 | 0.37† | |||

| ASAS40 | Week 12 Δ | 97 | −0.30* | 100 | −0.19 |

| Week 48 Δ | 90 | −0.39† | 90 | −0.16 | |

| SSS Fat metaplasia | Week 48 Δ | 88 | −0.28* | 87 | −0.07 |

| SSS Erosion | Week 48 Δ | 88 | 0.57† | 87 | 0.25‡ |

| SSS Ankylosis | Week 48 Δ | 88 | 0.11 | 87 | −0.08 |

| SSS Backfill | Week 48 Δ | 88 | −0.61† | 87 | −0.20 |

*p<0.01, †p<0.001, ‡p<0.05.

Clinical measures used observed case population. SSS scores include baseline and week 48; no values from an early termination visit were included.

For change from baseline to week 12 in the PBO/ETN group, the significant correlations were R=0.37 for CRP/ASDAS and R=0.22 for SPARCC SIJ/CRP. For change from baseline to week 48 in the PBO/ETN group, the significant correlations were: R=0.24 for SPARCC SIJ/ASDAS; R=0.32 for SPARCC SIJ/CRP; R=−0.46 for SPARCC SIJ/fat metaplasia; R=0.55 for SPARCC SIJ/erosion; R=−0.43 for SPARCC SIJ/backfill; R=0.62 for CRP/ASDAS; R=0.31 for CRP/BASDAI; and R=0.30 for CRP/BASFI.

ASAS40, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ETN, etanercept; PBO, placebo; R, Spearman correlation; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; SPARCC, Spondylitis Research Consortium of Canada; SSS, SPARCC MRI SIJ structural score.

For PBO/ETN, there was only a weak correlation between reduction in SPARCC SIJ inflammation and improvement in CRP (R=0.22) at 12 weeks, but upon switching to open-label ETN, significant correlations with ASDAS and CRP (R=0.24, p<0.05 and R=0.32, p<0.01) emerged at 48 weeks. The decrease in SPARCC SIJ inflammation score from baseline to week 48 correlated significantly with development of new fat metaplasia and backfill (R=−0.46, p<0.001 and R=−0.43, p<0.001) and with reduction in erosion score (R=0.55, p<0.001). There was no pattern of correlation between clinical outcomes and SPARCC spinal MRI score (see online supplementary table S2).

A decrease from baseline in CRP correlated with clinical changes in the ETN/ETN group (table 3). At week 12, CRP change correlated strongly with ASDAS improvement (R=0.61) and weakly with BASDAI, BASMI, BASFI and total back pain improvement (R ranged from 0.20 to 0.34). At week 48, these clinical correlations were preserved at approximately the 12-week levels and lower CRP correlated with a decrease in erosion score (R=0.25, p<0.05). For PBO/ETN, there was only a weak correlation (R=0.37) with improved ASDAS at 12 weeks, but after switching to open-label ETN, additional significant clinical correlations emerged at 48 weeks. There were no significant correlations with structural lesion changes.

Safety

Between weeks 12 and 48, 133/208 (64%) patients had an adverse event (AE) owing to treatment. The most common AEs (occurring in >5% of patients) were nasopharyngitis (15%) and upper respiratory tract infection (6%). Investigator-identified infections were reported in 21% of patients; none of the infections were serious. Four patients (2%) experienced serious AEs; one serious AE (fever) was considered to be related to the study drug. Two patients discontinued the study owing to the treatment-emergent AEs of bronchitis and fever. There were no reports of demyelinating disorder, active tuberculosis, malignancies or deaths. One case of herpes zoster was seen, which was not considered serious; ETN was discontinued and the AE resolved.

Discussion

Limited data are available on the 48-week efficacy, safety, MRI, health and productivity outcomes of using tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in nr-axSpA. In this analysis, clinical efficacy, patient-reported health-related quality-of-life, productivity and MRI outcomes improved between weeks 12 and 48 with ETN treatment; improvement of clinical and health outcomes was greater between weeks 12 and 24 than between weeks 24 and 48. After week 24 there was not an increase in the number of patients who responded, but those who did showed a greater response. This improvement is probably genuine, since there were few dropouts and clinical results correlated weakly by week 12 and then moderately by week 48 with objective improvement in SIJ MRI scores.

We compared 12- and 48-week clinical and SIJ MRI responses and observed significant improvement and correlation in certain outcomes. Although the natural history of axSpA and its relationship to SIJ inflammation is incompletely understood, these data suggest that ETN may mediate back pain relief and improve clinical indices in axSpA by decreasing inflammation in the SIJ, the site of disease symptoms.

In contrast to the clinical correlation with SIJ MRI, there was minimal correlation with spinal MRI SPARCC score changes, probably owing to the low level of spinal inflammation in patients with disease duration of <5 years. Notably, there was no significant spinal MRI improvement between weeks 12 and 48 using ASspiMRI-a scoring. The lack of consistent decreases in spinal MRI inflammation may be due to scoring differences between SPARCC and ASspiMRI-a, or a low spinal disease burden in this population with a short symptom duration.

Previous analyses of a correlation between MRI and clinical outcomes in patients with nr-axSpA yielded mixed results.10 15 There are several possible explanations for the discrepancy between previously published results and those presented here. Patients in this study had a relatively short symptom duration (<5 years) and not all patients in the other studies met ASAS criteria for nr-axSpA. Patients were chosen and images were interpreted by a central reader, thereby decreasing entry bias and minimising the possibility of admitting patients with radiographic evidence of AS.

One study limitation was an open-label design beyond 12 weeks and unblinding to the study drug. However, the low dropout rate and continued improvement in MRI reduce the likelihood that the clinical outcomes to 48 weeks resulted from a placebo effect. Additionally, efficacy results during the 48 weeks were imputed using the last observation carried forward and therefore do not represent the actual number of patients in the study at each time point. As expected, the OC population was smaller (figures 2 and 3), but the difference is slight, owing to the low dropout rate. As reported previously, clinical improvement occurred between 12 and 24 weeks, but no MRI was performed at week 24. Therefore, we cannot pinpoint precisely the timing of the correlation of clinical and MRI improvement seen between weeks 12 and 48 and it is possible that imaging improvement lagged behind clinical improvement.

Safety outcomes at 48 weeks were similar to those at 12 and 24 weeks and similar to those in the clinical trials that evaluated ETN for ankylosing spondylitis.26–29

In summary, these results demonstrate the long-term efficacy of ETN in treating patients with early nr-axSpA unresponsive to NSAIDs. Improvement in clinical, health, productivity and imaging outcomes was sustained to 48 weeks. These results were supported by correlations between decreased inflammation, as measured by MRI and CRP, and clinical outcomes. There were no new safety signals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients who participated in this study, as well as the investigators and medical staff at all of the participating centres.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study conception or design: WPM, MD, DvdH, JS, JB, GC, FVdB, IL, JW, RB, RP, BV, JFB. Acquisition of data: WPM, MD, DvdH, JS, JB, GC, FVdB, JW, RB, BV, JFB. Analysis or interpretation of data: WPM, MD, DvdH, JS, JB, GC, FVdB, IL, JW, HJ, LM, RB, RP, BV, SK, JFB. All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and all authors approved the final version to be published. Medical writing support was provided by Jennica Lewis of Engage Scientific Solutions.

Funding: This study was funded by Pfizer.

Competing interests: WPM has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Synarc and UCB and is the chief medical officer of CaRE Arthritis Ltd. MD has received consulting fees from Pfizer, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi-Aventis. DvdH has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB and Vertex and is the director of Imaging Rheumatology BV. JS has received consulting fees from Böhringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer and UCB. JB has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Celltrion, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. GC has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer and Roche and research grants from Pfizer. FVdB has received consulting and/or speaker fees from Abbvie, Celgene, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. IL, JW, HJ, LM, RB, RP, BV, SK and JFB are employees of Pfizer.

Ethics approval: The final protocol, any protocol amendments and informed consent form for this study were reviewed and approved for use by each study centre by a duly constituted institutional review board or independent ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bennett AN, McGonagle D, O'Connor P, et al. Severity of baseline magnetic resonance imaging–evident sacroiliitis and HLA–B27 status in early inflammatory back pain predict radiographically evident ankylosing spondylitis at eight years. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3413–18. 10.1002/art.24024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun J, Bollow M, Eggens U, et al. Use of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging with fast imaging in the detection of early and advanced sacroiliitis in spondylarthropathy patients. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:1039–45. 10.1002/art.1780370709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heuft-Dorenbosch L, Landewé R, Weijers R, et al. Combining information obtained from magnetic resonance imaging and conventional radiographs to detect sacroiliitis in patients with recent onset inflammatory back pain. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:804–8. 10.1136/ard.2005.044206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oostveen J, Prevo R, den Boer J, et al. Early detection of sacroiliitis on magnetic resonance imaging and subsequent development of sacroiliitis on plain radiography. A prospective, longitudinal study. J Rheumatol 1999;26:1953–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Maksymowych WP, et al. Spinal inflammation in the absence of sacroiliac joint inflammation on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with active nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:667–73. 10.1002/art.38283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83. 10.1136/ard.2009.108233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–44. 10.1136/ard.2008.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callhoff J, Sieper J, Weiß A, et al. Efficacy of TNFα blockers in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1241–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landewé R, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:39–47. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:815–22. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song IH, Weiß A, Hermann KGA, et al. Similar response rates in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis after 1 year of treatment with etanercept: results from the ESTHER trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:823–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barkham N, Keen HI, Coates LC, et al. Clinical and imaging efficacy of infliximab in HLA-B27-positive patients with magnetic resonance imaging-determined early sacroiliitis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:946–54. 10.1002/art.24408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, et al. Efficacy of adalimumab in the treatment of axial spondylarthritis without radiographically defined sacroiliitis: results of a twelve-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial followed by an open-label extension up to week fifty-two. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:1981–91. 10.1002/art.23606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, et al. Symptomatic efficacy of etanercept and its effects on objective signs of inflammation in early nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2091–102. 10.1002/art.38721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moltó A, Paternotte S, Claudepierre P, et al. Effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor α blockers in early axial spondyloarthritis: data from the DESIR cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:1734–44. 10.1002/art.38613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8. 10.1002/art.1780270401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. 2009. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003424.pdf

- 18.Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, et al. Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of spinal inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 53:502–9. 10.1002/art.21337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, et al. Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of sacroiliac joint inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:703–9. 10.1002/art.21445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Golder W, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging examinations of the spine in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, before and after successful therapy with infliximab: evaluation of a new scoring system. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1126–36. 10.1002/art.10883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. How do the EQ-5D, SF-6D and the well-being rating scale compare in patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:771–7. 10.1136/ard.2006.060384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Gasparini S, et al. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:25 10.1186/1477-7525-7-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:812–19. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maksymowych WP, Wichuk S, Chiowchanwisawakit P, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the spondyloarthritis research consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging sacroiliac joint structural score. J Rheumatol 2015;42:79–86. 10.3899/jrheum.140519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:47–53. 10.1136/ard.2010.138594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt J, Khariouzov A, Listing J, et al. Six-month results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of etanercept treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1667–75. 10.1002/art.11017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun J, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Huang F, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of etanercept versus sulfasalazine in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1543–51. 10.1002/art.30223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis JC, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3230–6. 10.1002/art.11325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis JC, van der Heijde DM, Braun J, et al. Efficacy and safety of up to 192 weeks of etanercept therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:346–52. 10.1136/ard.2007.078139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.