Abstract

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of tocilizumab (TCZ) with and without synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (sDMARDs) in a large observational study.

Methods

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with TCZ who had a baseline visit and information on concomitant sDMARDs were included. According to baseline data, patients were considered as taking TCZ as monotherapy or combination with sDMARDs. Main study outcomes were the change of Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and TCZ retention. The prescription of TCZ as monotherapy was analysed using logistic regression. CDAI change was analysed with a mixed-effects model for longitudinal data. TCZ retention was analysed with a stratified extended Cox model.

Results

Multiple-adjusted analysis suggests that prescription of TCZ as monotherapy varied according to age, corticosteroid use, country of the registry and year of treatment initiation. The change of disease activity assessed by CDAI as well as the likelihood to be in remission were not significantly different whether TCZ was used as monotherapy or in combination with sDMARDs in a covariate-adjusted analysis. Estimates for unadjusted median TCZ retention were 2.3 years (95% CI 1.8 to 2.7) for monotherapy and 3.7 years (lower 95% CI limit 3.1, upper limit not estimable) for combination therapies. In a covariate-adjusted analysis, TCZ retention was also reduced when used as monotherapy, with an increasing difference between mono and combination therapy over time after 1.5 years (p=0.002).

Conclusions

TCZ with or without concomitant sDMARDs resulted in comparable clinical response as assessed by CDAI change, but TCZ retention was shorter under monotherapy of TCZ.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Treatment, DMARDs (biologic), DMARDs (synthetic)

Introduction

Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) have markedly changed the management and outcome of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Tocilizumab (TCZ), a monoclonal anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, has proven to be efficacious in patients who did not respond to methotrexate (MTX) or other synthetic DMARDs (sDMARDs), as well as after failure to respond to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists, and to prevent the progression of structural damage.1–3 These findings have led to the inclusion of TCZ in the algorithm of RA management as a first-line bDMARD after MTX failure similar to TNF antagonists or abatacept.4

Most international guidelines recommend the use of bDMARDs in combination with MTX or other sDMARDs in case MTX is not tolerated or contraindicated.4 These recommendations are primarily based on the observation that MTX enhances the efficacy of TNF antagonists in both clinical trials and observational studies.5–7 In two randomised clinical trials including adult patients with RA with inadequate response to MTX, patients were randomised to receive either intravenous TCZ as monotherapy or in combination with MTX. The results of these studies showed that, when considering some endpoints, the combination with MTX offered some advantage over TCZ as monotherapy. However, both strategies were associated with meaningful clinical and radiographic responses.8–11 To date, however, data from large, observational, multinational studies on TCZ effectiveness are lacking.

The objective of this study, based on data from several European registries, was to analyse the characteristics of patients who were treated with TCZ as monotherapy and the effectiveness of TCZ, with particular attention to its use as monotherapy or in combination with MTX or different sDMARDs.

Methods

Patient population

The TOcilizumab Collaboration of European Registries in RA is an investigator-led, industry-supported initiative with the aim to evaluate clinical aspects of TCZ use in patients with RA. Each registry obtained ethical approval for the use of anonymised data for research separately. The data-contributing registries were ATTRA (http://www.attra.registry.cz), Czech Republic (CS); DANBIO (http://www.danbio-online.dk), Denmark (DK); ROB-FIN (http://www.reumatologinenyhdistys.fi), Finland (FI); DREAM-RA (http://www.dreamregistry.nl), the Netherlands (NL); NOR-DMARD, Norway (NO); Reuma.pt (http://www.reuma.pt), Portugal (PT); ARBITER, Russia (RU); BioRx.si, Slovenia (SI); SRQ (Swedish Rheumatology Quality Register, http://www.srq.nu), Sweden (SE); SCQM (Swiss Clinical Quality Management in Rheumatic Diseases, http://www.scqm.ch), Switzerland (CH). All patients included in the different registries who had started treatment with TCZ by the end of 2013/beginning of 2014 were considered eligible for the present study if (1) the patient had a diagnosis of RA established by a rheumatologist, (2) the patient had initiated TCZ treatment after the end of 2008 at an age of 18 years or older, (3) a baseline visit within 90 days prior to start of TCZ was available and (4) baseline information on the use of sDMARD co-therapy were available. In the rare case of patients who have experienced several treatment courses (TCs) with TCZ (identified by a difference of at least 60 days between stop and restart of TCZ treatment) after 2008 for which the above-stated inclusion criteria were met, the earliest one was selected. Any follow-up visit for which the available information allowed to conclude, unambiguously, that it had occurred after the start of TCZ and before 60 days after stop of TCZ treatment was considered valid and included.

Exposure of interest

TCZ treatments were classified as either monotherapy (‘TCZ’) or as one of three types of combination therapy with sDMARDs such as (1) with MTX only (‘TCZ+MTX’), (2) with MTX and at least one other sDMARD (‘TCZ+MTXplus’) or (3) with at least one other sDMARD (‘TCZ+other’), depending on the presence of concomitant sDMARDs at baseline.

Study outcomes

Our main focus was on investigating the change of disease activity following initiation of TCZ therapy in terms of Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and TCZ retention in relation to the type of TCZ therapy. TCZ retention was defined as the time from the start date of TCZ treatment until the TCZ discontinuation date. If TCZ had not been discontinued, TCZ retention was censored at the date of the last reported follow-up visit. For TCZ retention, only patients who had not been lost to follow-up immediately after start of TCZ and who were not from Russia where regular treatment with TCZ had been discontinued for administrative reasons in a number of patients were regarded eligible. We also used the disease activity score (DAS) 28 as a secondary outcome measure. The DAS28 calculation for a given patient was based on either the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) three*item formula (28 joint counts for tender and swollen joints and the ESR in mm/h) or the C reactive protein (CRP) three-item formula (with CRP in mg/L), depending on the amount of available and valid information for ESR and CRP, with a preference for the ESR-based formula. For 60% of patients, the ESR-based formula was used.

Covariates

The baseline covariates considered were sex, age, disease duration, number of previously used biologics, seropositivity (presence of rheumatoid factor (RF) or anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP)), corticosteroid use, functional disability (Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)), DAS28, year of TCZ treatment start and country of registry. Details on covariates are described in the online supplementary material.

Statistical methods

The prescription of TCZ as monotherapy versus in combination with sDMARDs in relation to patient characteristics at baseline was analysed using logistic regression analyses. CDAI and DAS28 change over time was visualised by means of smoothing using a local quadratic regression approach and analysed with mixed-effects models for longitudinal data. TCZ retention was analysed using Kaplan–Meier and Cox models, with the addition of time-varying covariate effects (extended Cox models). The frequency of disease remission (CDAI <2.8 or DAS28 <2.6) under treatment was assessed at various times post-TCZ start. For 16–34% of patients, depending on the analysis, information for at least one covariate was missing. We reanalysed our main analyses (prescription of monotherapy, TCZ retention and CDAI/DAS28 change) based on multiple imputation of missing covariate data. Detailed information on statistical methods, models and software is available from the online supplementary material.

Results

A total of 2057 patients fulfilling all the inclusion criteria and providing a total of 13 131 follow-up visits were retrieved from the different registries. Of the 1498 patients with available information, all but 52 started TCZ treatment with a dose of ≥6 mg/kg. A flow chart of the patients considered eligible and included in the different analyses is shown in online supplementary figure S1.

Baseline patient characteristics associated with TCZ prescription

TCZ was most frequently initiated in combination with MTX (1011 TCs), followed by TCZ as monotherapy (577 TCs), TCZ with sDMARDs other than MTX (285 TCs) and, lastly, by TCZ in combination with MTX and other sDMARD(s) (184 TCs). For the majority of patients (89% for TCZ, 68% for TCZ+MTX, 61% for TCZ+MTXplus and 73% for TCZ+other), sDMARD co-therapy did not change over time. A description of patient characteristics by type of TCZ treatment is provided in online supplementary table S1.

The results from a multiple-adjusted analysis of the probability of prescribing TCZ as monotherapy suggest that (1) countries differ in their prescription attitude with respect to TCZ as monotherapy, (2) TCZ as monotherapy has become more frequent over the years, (3) it is more frequently prescribed to older patients with RA and (4) it is more frequently prescribed to patients without concomitant corticosteroid therapy (table 1). Due to their effect on the prescription of monotherapy, these four covariates must be regarded as potential confounding variables with respect to TCZ treatment.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline covariates and their relation to prescription of tocilizumab (TCZ) as monotherapy

| Prescription of TCZ as monotherapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Summary (n=2057) | Proportion of mono (%) | OR (95% CI) for mono (n=1359) | |

| Age (years) | 55 (13.1) 56 (46–64) |

1.38 (1.11 to 1.71) per 20 years more | ||

| Sex (%) (n=2056) | Male | 21 | 24 | Reference |

| Female | 79 | 29 | 1.30 (0.92 to 1.83) | |

| Disease duration (years) (n=1900) | 11.4 (9.5) 9.1 (4.1–16.1) |

1.11 (0.96 to 1.27) per 10 years more | ||

| Seropositivity (%) (n=1891) | No | 18 | 27 | Reference |

| Yes | 82 | 28 | 1.08 (0.75 to 1.54) | |

| Number of prior biologics (%) (n=2056) |

0 | 19 | 29 | Reference |

| 1 | 26 | 26 | 0.82 (0.54 to 1.25) | |

| ≥2 | 55 | 28 | 0.76 (0.51to 1.13) | |

| Corticosteroids (%) (n=2011) | No | 51 | 33 | Reference |

| Yes | 49 | 22 | 0.74 (0.56 to 0.99) | |

| DAS28 (n=1914) | 5.0 (1.4) 5.1 (4.1–6.0) |

1.14 (0.89 to 1.45) per 2 units more | ||

| HAQ (n=1673) | 1.4 (0.7) 1.5 (1.0–2.0) |

0.95 (0.77 to 1.19) per 1 unit more | ||

| Year of TCZ initiation (%) | 2009 | 15 | 19 | Reference |

| 2010 | 23 | 22 | 1.23 (0.78 to 1.96) | |

| 2011 | 20 | 24 | 1.40 (0.87 to 2.25) | |

| 2012 | 22 | 35 | 2.07 (1.30 to 3.28) | |

| 2013 | 20 | 38 | 2.58 (1.62 to 4.10) | |

| Country (%) | Czech Republic | 12.9 | 23 | 0.66 (0.39 to 1.12) |

| Denmark | 35.5 | 31 | 0.92 (0.60 to 1.39) | |

| Finland | 2.3 | 11 | 0.36 (0.10 to 1.27) | |

| The Netherlands | 2.4 | 28 | – | |

| Norway | 3.8 | 52 | – | |

| Portugal | 8.4 | 15 | 0.46 (0.24 to 0.87) | |

| Russia | 4.1 | 11 | 0.30 (0.12 to 0.79) | |

| Slovenia | 9.5 | 21 | 0.28 (0.14to 0.55) | |

| Sweden | 6.4 | 38 | 1.41 (0.82 to 2.44) | |

| Switzerland | 14.7 | 34 | Reference | |

Sample sizes (n) equal the number of eligible patients presented in the header of column ‘Summary’ unless indicated otherwise. The column named ‘Summary’ provides a description of covariates in terms of mean (SD) and median (IQR) for discrete or continuous covariates and percentages for categorical covariates. The column named ‘Proportion of mono’ provides the frequency of monotherapy-initiated TCZ treatment for each category of a categorical covariate. The last column presents estimated ORs and 95% Wald CIs for prescribing TCZ as monotherapy (as compared to any type of combination therapy) based on multiple logistic regression. ORs for discrete or continuous covariates are presented for a difference corresponding approximately to the IQR. For categorical covariates, ORs with respect to the chosen reference category are shown. p Values from likelihood ratio tests for categorical covariates with more than two categories were 0.41 for number of prior biologics, <0.0001 for year of TCZ initiation and <0.0001 for country. The multiple logistic regression is based on all TCs with complete covariate information. The Netherlands (patchy data) and Norway (no HAQ recorded) lack TCs with complete covariate information.

DAS, disease activity score; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; TC, treatment courses.

The results from an analysis based on multiple imputation of missing covariates were comparable to those from the reported complete-case analysis (data not shown).

Change of disease activity

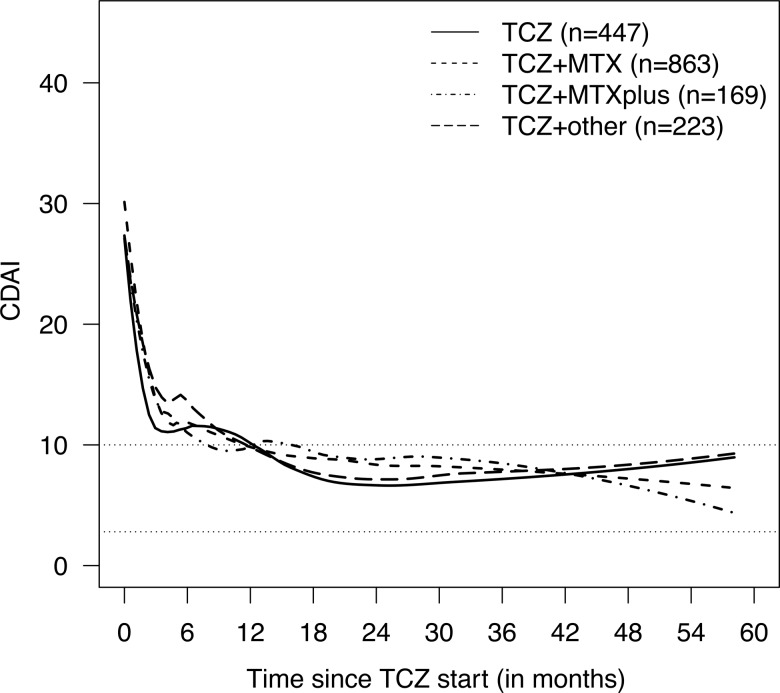

The CDAI at baseline of TCZ initiation was influenced by country of registry, year of TCZ treatment initiation, the number of prior biologics and sex (online supplementary table S2). The CDAI decreased rapidly after the start of TCZ, regardless of whether TCZ was used as monotherapy or in combination with sDMARDs (figure 1). A virtually identical result was observed when disease activity was assessed using DAS28 (online supplementary figure S2). A covariate-adjusted longitudinal analysis of both CDAI and DAS28 provided similar results with respect to the effect of TCZ treatment as monotherapy or in combination with sDMARDs. The estimated differences in CDAI between the four treatment groups at various times based on the longitudinal model are shown in table 2. Some covariates had significant effects on CDAI change, such as country of registry, year of TCZ treatment initiation and number of previously used biologics (online supplementary table S2). Similar results were obtained for DAS28 (see online supplementary material). An analysis based on multiple imputation of missing covariates provided results comparable to those from the complete-case analysis, especially with respect to the effect of type of TCZ treatment (data not shown). Combining the different combination therapy groups into one group resulted in the same conclusions for CDAI and DAS28 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Smoothed time courses of Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) by tocilizumab (TCZ) treatment. The data represent all 1702 eligible patients with at least one CDAI value totalling 9943 observations. Data were smoothed separately for each TCZ treatment using local quadratic regression. Treatment groups ‘TCZ’, ‘TCZ+ methotrexate (MTX)’, ‘TCZ+MTXplus’, and ‘TCZ+other’ represent TCZ as monotherapy and in combination with MTX, MTX+other synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (sDMARD(s)), and at least one sDMARD other than MTX, respectively. Numbers of patients providing CDAI information beyond 12, 24, 36 and 48 months were 162, 76, 32 and 7 for ‘TCZ’, 427, 262, 133 and 41 for ‘TCZ+MTX’, 80, 41, 21 and 11 for ‘TCZ+MTXplus’, and 90, 55, 27 and 11 for ‘TCZ+other’, respectively. Of note, all Swedish patients were excluded due to lack of a global physician's assessment of disease in this registry.

Table 2.

Estimated differences in Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) between type of tocilizumab (TCZ) treatments at various times

| Time (months) | TCZ+MTX vs TCZ Estimate (95% CI) |

TCZ+MTXplus vs TCZ Estimate (95% CI) |

TCZ+other vs TCZ Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.44 (−0.94 to 1.81) | 1.54 (−0.49 to 3.57) | 1.90 (−0.01 to 3.80) |

| 6 | 0.30 (−0.97 to 1.57) | 1.38 (−0.51 to 3.27) | 1.62 (−0.14 to 3.38) |

| 12 | 0.10 (−1.10 to 1.30) | 1.15 (−0.64 to 2.93) | 1.22 (−0.44 to 2.87) |

| 18 | −0.10 (−1.35 to 1.14) | 0.91 (−0.92 to 2.74) | 0.81 (−0.87 to 2.51) |

| 24 | −0.31 (−1.70 to 1.08) | 0.68 (−1.34 to 2.69) | 0.41 (−1.47 to 2.29) |

Estimated differences and 95% Wald-type CIs for each combination treatment versus monotherapy based on a covariate-adjusted longitudinal mixed effects analysis are shown. A positive difference means that CDAI under monotherapy is estimated lower than under the respective combination treatment at this time point. The p values (from F-tests) for an effect of type of TCZ treatment were 0.16 for the initial linear decrease over 2 months and 0.46 for the subsequent linear phase. All 1428 eligible patients with information on CDAI and complete covariate information were included. The distribution of patients between the four TCZ treatments was comparable to the whole population. Overall, 281 patients lacked a baseline CDAI and 242 provided only one CDAI value (for 176 of these this was the baseline value). Of note, all Swedish patients were excluded due to lack of a global physician's assessment of disease in this registry. All patients from the Netherlands were excluded due to incomplete data.

MTX, methotrexate.

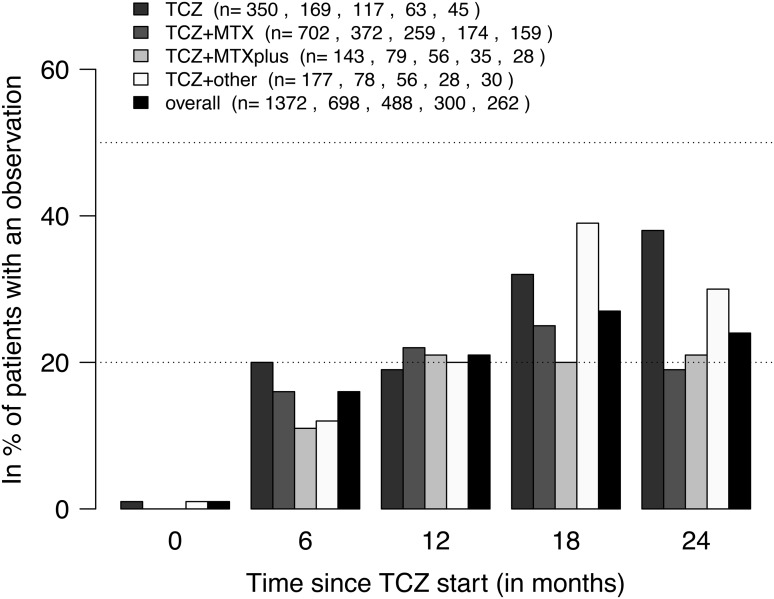

The frequency of disease remission in terms of CDAI (CDAI<2.8), as assessed at various times after TCZ initiation, was about 20% overall (figure 2). At 6 months, the covariate-adjusted OR for CDAI remission in patients treated with TCZ in combination with MTX versus TCZ as monotherapy was 1.03 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.40). The respective OR at 12 months was 1.06 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.42). For ‘TCZ+MTXplus’ and ‘TCZ+other’ versus ‘TCZ’, the ORs were 0.79 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.27) and 0.77 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.16) at 6 months and 0.81 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.28) and 0.81 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.21) at 12 months. Comparable data were observed for DAS28 remission (see online supplementary material), with the exception of an overall higher frequency of DAS28 remission in all treatment groups.

Figure 2.

Frequency of Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) remission (CDAI <2.8) by tocilizumab (TCZ) treatment. The numbers (n) shown in the legend indicate the number of ongoing treatment courses for which a CDAI value was available within ±30 days of a certain post-baseline time point. At none of the time points was there a significant difference between TCZ treatment types (Fisher's exact tests at 5% level). Treatment groups ‘TCZ’, ‘TCZ+ methotrexate (MTX)’, ‘TCZ+MTXplus’ and ‘TCZ+other’ represent TCZ as monotherapy and in combination with MTX, MTX+other synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (sDMARD(s)) and at least one sDMARD other than MTX, respectively.

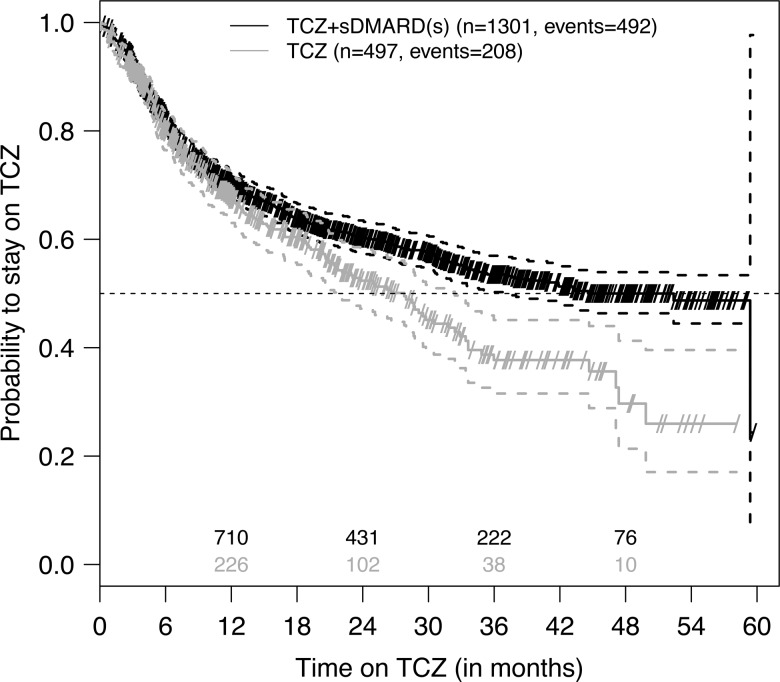

TCZ retention

Discontinuation of TCZ therapy was observed in 700 (39%) of the 1798 eligible patients. Main causes for discontinuation were lack of effectiveness (mentioned for 50% of discontinued patients for monotherapy and 52% for combination therapies) and safety issues (mentioned for 32% of discontinued patients for monotherapy and 28% for combination therapies). In 23 patients (5 from monotherapy and 18 from combination therapies), TCZ was discontinued due to disease remission.

Unadjusted estimates of TCZ retention curves suggest that, at later times, TCZ is more often discontinued when initiated as monotherapy, as compared to when initiated in combination therapy (all three types of combination therapy combined) (figure 3). Respective estimates for unadjusted median retention were 2.3 years (95% CI 1.8 to 2.7) for monotherapy and 3.7 years (lower 95% CI limit: 3.1, upper limit not estimable; see figure 3) for combination therapies. This conjecture was supported by the finding of a time-dependent effect of TCZ treatment on the hazard for TCZ discontinuation in both an unadjusted and covariate-adjusted analysis. In both cases, we observed an increasing difference with time after 1.5 years (table 3). Of all other covariates, only seropositivity and HAQ were found to significantly affect the hazard for TCZ discontinuation (online supplementary table S4). There were also major differences in TCZ retention curves between countries (online supplementary figure S4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of tocilizumab (TCZ) retention by TCZ treatment. These unadjusted data represent all 1798 eligible patients. Small diagonal lines indicate censored retention times (at date of last follow-up visit), dashed lines 95% CIs for the survival curves and numbers above the x-axis denote the numbers of patients known to be still at risk for TCZ discontinuation (ie, still on TCZ and not yet lost to follow-up). Treatment groups ‘TCZ’ and ‘TCZ+ synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (sDMARD(s))’ represent TCZ as monotherapy and in combination with sDMARDs, respectively. For ‘TCZ+sDMARD(s)’ the upper 95% CI line does not cross the 50% line for the probability to stay on TCZ resulting in an unestimable upper 95% CI limit for the median retention time.

Table 3.

Effect of tocilizumab (TCZ) monotherapy on hazard for TCZ discontinuation over time

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCZ vs TCZ+sDMARD(s) | |||

| In first 1.5 years | 1.10 | 0.87 to 1.39 | 0.41* |

| At 2 years | 1.54 | 1.19 to 1.99 | 0.003† |

| At 3 years | 3.00 | 1.62 to 5.56 | |

| At 4 years | 5.86 | 2.07 to 16.57 | |

Shown are estimated HRs, 95% Wald CIs and associated p values at various times based on a country-stratified, covariate-adjusted extended Cox proportional hazards analysis of TCZ retention.

*p Value for the effect of TCZ treatment (monotherapy vs combination therapy) in the first 1.5 years,

†p Value for the change in the effect of TCZ treatment with time after 1.5 years. All 1198 eligible patients who had not been lost to follow-up immediately, were not from Russia and had complete covariate information were included (number of events=464). The distribution of patients and events between TCZ treatments was comparable to the case with all 1798 eligible patients. Of note, all patients from Norway and the Netherlands were excluded due to lack of complete covariate information.

sDMARD, synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

The results from the analysis based on multiple imputation of missing covariates were comparable to those from the reported complete-case analysis, particularly with respect to the effect of type of TCZ treatment (data not shown).

Discussion

This study included a large number of patients with RA from different European countries treated with TCZ in either monotherapy or in combination with MTX or different combinations of sDMARDs. Prescription of TCZ as monotherapy varied according to some intrinsic patient characteristics (age and use of corticosteroids), as well as the extrinsic factors, country of the registry and year of treatment initiation. The change of disease activity assessed by CDAI and DAS28, as well as the likelihood to be in remission, was not significantly different whether TCZ was used as monotherapy or in combination with sDMARDs. However, TCZ retention was more prolonged when TCZ was prescribed in combination with sDMARDs.

Despite current recommendations to use bDMARDs with MTX or other sDMARDs, several reports from different countries show that in routine practice approximately 30% of patients with RA receive bDMARDs as monotherapy. In this study, we observed that older patients were more likely to be treated with TCZ as monotherapy. This result is consistent with two other observational studies that have shown that monotherapy with bDMARDs is more often prescribed to older patients with also longer disease duration, a higher number of previous DMARDs and more comorbidities.7 12 Thus, it is likely that patients treated in TCZ monotherapy represent a subgroup of patients who are more difficult to manage and exhibit intolerance to MTX and other sDMARDs. Unfortunately, comorbidities were not captured by most registries, thus limiting our analysis on the influence of other medical conditions on the use of TCZ as monotherapy. However, it is plausible that older multimorbid patients could have been preferentially treated with TCZ alone rather than in combination with MTX or other sDMARDs.

Taking advantage of the inclusion of registries representing different European countries, we have observed significant differences regarding the prescription of TCZ. Variations regarding local treatment recommendations, as well as TCZ licensing (in combination with MTX or sDMARDs), most likely explain these variations. The significant increase in the prescription of TCZ as monotherapy over the years, and particularly after 2012, is likely explained by the results of studies demonstrating that TCZ as monotherapy is a reasonable treatment option.8 10 Furthermore, TCZ as monotherapy was significantly more efficacious than adalimumab as monotherapy in patients with RA with inadequate response to MTX.13

The efficacy of TCZ as monotherapy in comparison to its use in combination with MTX or other sDMARDs in patients with RA with inadequate response to MTX has been examined in clinical trials. The ACT-RAY study examined the efficacy and safety of switching to TCZ monotherapy or adding TCZ to MTX in patients with active disease despite MTX therapy. The results after 24 weeks did not show any advantage of the combination over TCZ as monotherapy.8 After 52 weeks, patients treated with TCZ in combination with MTX had a significantly higher percentage of DAS28 remission, a lower erosion score and a higher percentage of patients without radiographic progression. Of note, all other clinical endpoints did not differ between the two treatment groups.9 After 104 weeks, the two treatment groups were also significantly different regarding changes in total radiographic and erosion scores but not for clinical endpoints.10 Using a similar study design, other investigators showed that ACR response rates and the percentage of patients who achieved DAS28 remission after 52 weeks were not significantly different in the monotherapy group compared with the combination group (70.3% vs 72.2%).14 Taken together, the results of these clinical trials suggest that concomitant use of MTX provides a slight advantage for some endpoints. A 24-week large open-labelled study comparing the efficacy and safety of TCZ used as monotherapy or in combination with sDMARDs in 1681 patients with RA with inadequate response to sDMARDs or TNF inhibitors found that TCZ had comparable efficacy and safety when used as monotherapy or in combination with sDMARDs.15 In an observational registry study from Japan, the odds to achieve DAS28 remission were not different in patients treated with TCZ alone or in combination with MTX. However, there was an increased probability for achieving remission for TCZ in combination compared with TCZ alone in a subset of patients with high baseline DAS28 >5.1.16

We observed that TCZ retention was shorter in patients treated with TCZ as monotherapy compared with the groups treated in combination with sDMARDs. Drug retention can be influenced by many factors, including effectiveness, tolerance, remission, costs and patients’ or physicians’ preferences. We could not easily explain this finding by differences in effectiveness or safety. The marked variations of treatment retention observed between registries could be reflective of differences in local licensing, treatment recommendations, economic situation or available treatment options. Of note, the difference in TCZ retention between mono and combination therapy of TCZ seemed irrelevant for the first 1.5 years and then increased over time. It is thus possible that after an initial improvement in disease activity patients under TCZ monotherapy start to flare sooner than patients under TCZ in combination with sDMARDs, leading to an increased hazard for TCZ discontinuation at later times. However, our data analysis did not show such a behaviour (data not shown). Of note, after a 104-week follow-up, the proportion of patients in the monotherapy group who withdrew because of lack of efficacy was numerically larger than in the combination treatment group in ACT-RAY.10

Our study included a relatively large group of patients followed longitudinally for several years, representative of different practices in Europe. It may, however, suffer from potential limitations inherent to the analysis of observational data. Confounding by indication may result in biased estimates for the effect of type of TCZ treatment. We counteracted this in our covariate-adjusted analyses, but we cannot exclude the presence of residual confounding by other unmeasured confounders. For example, apart from the number of biologics received prior to TCZ treatment, we have not considered any other information relating to previous treatments. Another possible confounder missing from our investigations is the presence of comorbidities. Missing data is another potential concern. We have rerun some of our analyses based on multiple imputation of missing covariates and obtained comparable results to our complete-case analysis, particularly for the type of TCZ treatment. We prefer the complete-case analysis over the multiple imputation approach for several reasons. A complete-case analysis is unbeatable in its simplicity and non-error-prone implementation. Furthermore, after careful consideration of the likely missingness mechanisms at work, we concluded that a complete-case analysis is more likely to give unbiased results than an analysis based on multiple imputation.17–19 Our international collaboration was useful to increase the number of patients treated with TCZ for our analyses. However, we observed important heterogeneity between countries with a clear impact on treatment habits, the prescription of TCZ, as well as in drug retention that may lead to difficulty in interpreting the data.

In conclusion, we have found that age, corticosteroid use, country of residence and year of treatment initiation influenced prescription of TCZ as monotherapy. TCZ with or without concomitant sDMARDs resulted in comparable clinical response, but TCZ retention was reduced under TCZ monotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The spelling of the 8th author's surname has been corrected.

Twitter: Follow M. Victoria Hernández at @MD27409

Contributors: All the authors have provided substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition of the data and the interpretation of data. MR performed the statistical analysis. CG and MR made the first draft. All the other authors participated in the final drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the final approval of the version published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The TOCERRA collaboration is funded by Roche.

Competing interests: CG has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, BMS, Roche, Pfizer, Celgene, MSD, Janssen Cilag, Amgen, UCB, and received research funding from Roche, AbbVie, MSD and Pfizer. The SCQM Foundation is funded by the Swiss Society of Rheumatology, and by Abbvie, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, UCB and Janssen. In addition, SCQM has received project-based financial supports from various institutions and companies (eg, Arco Foundation, Switzerland, or Schweizerischer Verein Balgrist, Switzerland). MR is employed by SCQM. MLH has received fees for consulting and/or research grant from BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Abbott, UCB and Roche. DANBIO is funded by hospital authorities in Denmark and has received unrestricted grants from AbbVie, BMS, Hospira, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. E-MH has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from MSD and AbbVie; and received research funding to Aarhus University Hospital from AbbVie and Roche. KP has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Roche, Amgen, MSD, BMS, UCB and Egis. ATTRA was partially supported by the project from the Czech Ministry of Health for conceptual development of research organisation 023728 (Institute of Rheumatology). MT has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from Abbvie, Roche, MSD, and Pfizer paid to Revmatic d.o.o. BioRx.si has received funding for clinical research paid to Društvo za razvoj revmatologije from AbbVie, Roche, Medis, MSD and Pfizer. HC has received fees for consulting from Roche and Pfizer. Reuma.pt is supported by unrestricted grants from Abbvie, MSD, Roche and Pfizer. GL has received fees for consulting from BMS, Roche, MSD, AbbVie and Pfizer. The ARBITER registry is supported by a non-commercial partnership with ‘Equalrights to life’. DCN has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from Abbvie, BMS, MSD, Roche, UCB and Pfizer. ROB-FIN is funded by AbbVie, Hospira, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. EL has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Hospira, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. IA has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from MSD, AbbVie, Roche, Pfizer, BMS and UCB. PLMCvR has received consulting fees and research grants from AbbVie, Pfizer, Roche, Eli Lilly, BMS and UCB. DREAM-RA is funded by AbbVie, Roche, Pfizer, UCB and BMS. RvV has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Biotest, BMS, Crescendo, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, UCB and Vertex; and research grants from AbbVie, BMS, GSK, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. TKK has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Hospira, Merck-Serono, MSD, Orion Pharma, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz and UCB and received research funding to Diakonhjemmet Hospital from AbbVie, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. NOR-DMARD was previously supported with research funding to Diakonhjemmet Hospital from AbbVie, BMS, MSD/Schering-Plough, Pfizer/Wyeth, Roche and UCB.

Ethics approval: EC from different institutes for the collection of clinical data in registries.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the data are presented in the main manuscript and in the online supplementary material.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. . Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:987–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, et al. . IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1516–23. 10.1136/ard.2008.092932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischmann RM, Halland AM, Brzosko M, et al. . Tocilizumab inhibits structural joint damage and improves physical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to methotrexate: LITHE study 2-year results. J Rheumatol 2013;40:113–26. 10.3899/jrheum.120447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Breedveld FC, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73: 492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. . The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, et al. . Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:675–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soliman MM, Ashcroft DM, Watson KD, et al. . Impact of concomitant use of DMARDs on the persistence with anti-TNF therapies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:583–9. 10.1136/ard.2010.139774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougados M, Kissel K, Sheeran T, et al. . Adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in methotrexate inadequate responders: 24-week symptomatic and structural results of a 2-year randomised controlled strategy trial in rheumatoid arthritis (ACT-RAY). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:43–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dougados M, Kissel K, Conaghan PG, et al. . Clinical, radiographic and immunogenic effects after 1 year of tocilizumab-based treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis: the ACT-RAY study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:803–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huizinga TW, Conaghan PG, Martin-Mola E, et al. . Clinical and radiographic outcomes at 2 years and the effect of tocilizumab discontinuation following sustained remission in the second and third year of the ACT-RAY study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:35–43. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi T, Kaneko Y, Atsumi T, et al. . Adding Tocilizumab or switching to Tocilizumab monotherapy in RA patients with inadequate response to Methotrexate: 24-week results from a randomized controled study (surprise study). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(Suppl 3):62 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabay C, Riek M, Scherer A, et al. . Effectiveness of biological DMARDs in monotherapy versus in combination with synthetic DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis—data from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) Published Online First: 27 Apr 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, et al. . Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet 2013;381:1541–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi T, Kaneko Y, Atsumi T, et al. . Clinical and radiographic effects after 52-week of adding Tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab in RA patients with inadequate response to methotrexate: results from a prospective randomized controlled study (SURPRISE study). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(Suppl 2):686 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-eular.2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bykerk V, Östör AJK, Alvaro-Gracia J, et al. . Comparison of tocilizumab as monotherapy or with add-on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to previous treatments: an open-label study close to clinical practice. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:563–71. 10.1007/s10067-014-2857-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kojima T, Yabe Y, Kaneko A, et al. . Importance of methotrexate therapy concomitant with tocilizumab treatment in achieving better clinical outcomes for rheumatoid arthritis patients with high disease activity: an observational cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:113–20. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White IR, Carlin JB. Bias and efficiency of multiple imputation compared with complete-case analysis for missing covariate values. Stat Med 2010;29:2920–31. 10.1002/sim.3944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allison PD. Multiple imputation for missing data: a cautionary tale. Sociol Method Res 2000;28:301–9. 10.1177/0049124100028003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd edn, Oxford: Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.