Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the structural and functional maturation of the choriocapillaris (CC). We sought to determine when fenestrations formed, pericytes invest the capillaries and endothelial cells became functional.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry was performed on cryopreserved sections of embryonic/fetal human eyes from 7 to 22 weeks gestation (WG) using antibodies against PAL-E, PV-1 (fenestrations), carbonic anhydrase IV (CA IV), eNOS, and alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and NG2 (two pericyte markers) and endothelial cell (EC) markers (CD34, CD31). Alkaline phosphatase (APase) enzymatic activity was demonstrated by enzyme histochemistry. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on 11, 14, 16 and 22 WG eyes. Adult human eyes were used as positive controls.

Results

All EC markers were present in CC by 7 WG. PAL-E, CA IV and eNOS immunoreactivities and APase activity were present in CC by 7–9 WG. TEM analysis demonstrated how structurally immature this vasculature was even at 11 WG: no basement membrane, absence of pericytes, and poorly formed lumens that were filled with filopodia. The few fenestrations that were observed were often present within the luminal space in the filopodia. Contiguous fenestrations and significant PV-1 were not observed until 21–22 WG. αSMA was prominent at 22 WG and the maturation of pericytes was confirmed by TEM.

Conclusions

It appears that EC and their precursors have several mature functional characteristics well before they are structurally mature. Although EC make tight junctions early in development, contiguous fenestrations and mature pericytes occur much later in development.

Keywords: choriocapillaris, fenestrations, fetal, immunohistochemistry, pericytes, ultrastructure

INTRODUCTION

Human choroid is a thin, highly vascularized and pigmented tissue that forms the posterior portion of the uveal tract (the iris, ciliary body, and choroid). The inner boundary of the choroid is Bruch’s membrane, upon which the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) monolayer is present. The vascular system of the choroid consists of three layers in the posterior pole. The anterior layer is the choriocapillaris (CC), composed of broad, flat capillaries with 20 to 50 µm lumens. The capillaries are arranged in a honeycomb-like pattern that appears lobular, especially in the posterior pole. The middle layer of intermediate sized arterioles and venules is called Sattler’s layer. Haller’s layer, the outermost layer of choroidal vasculature, is composed of large arteries measuring 40 to 90 µm and large veins measuring 20 to 100 µm. This distinct three layer choroidal vasculature tapers to a single layer in the periphery that has ladder-like vascular pattern.1

The CC and RPE are closely associated not only anatomically but also functionally. The highly metabolically active photoreceptors are dependant on the CC for nutrients and oxygen and removal of the end products after photoreceptor shedding and RPE digestion. This material transport is done through the fenestrations of the CC. Most studies suggest that these unique structures exist only on the side of CC towards the RPE. VEGF secreted from the basal side of the RPE is thought to be necessary in maintaining the CC fenestrations.2

We have recently demonstrated that the initial human embryonic and early fetal CC develops by hemo-vasculogenesis: differentiation of endothelial, hematopoietic and erythropoietic cells from a common precursor, the hemangioblast.3 At 6–7 WG, erythroblasts [nucleated erythrocytes expressing epsilon hemoglobin (Hbε)] were observed within the islands of precursor cells (blood-island-like formations) in the CC layer and scattered within the forming choroidal stroma. Often the Hbε+ cells co-expressed endothelial cell (CD31, CD39), hematopoietic (CD34), and angioblast markers (CD39, VEGFR-2) suggesting a common precursor. By 8–12 WG, most of the erythroblasts had disappeared and vascular lumen became apparent. At 14–23 WG, some endothelial cells were proliferating on the scleral side of CC in association with forming deeper vessels suggesting that angiogenesis was involved in anastomosis of the CC with large choroidal blood vessels. The current study investigates the functional and morphological maturity of embryonic and fetal CC using enzyme and immunohistochemistry (endothelial cell markers like CD314 and 345 and pericyte markers like alpha smooth muscle actin6, 7 and NG2)8–10 (Table 1) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Table 1.

Antibodies Used to Detect Protein Markers

| protein | function | marker for | antibody, manufacturer, (titer) |

references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD31 | adhesion molecule | hematopoietic cells and endothelial cells |

mouse anti-CD31, Dako, Carpenteria, CA (1:500) |

4 |

| CD34 | glycoprotein | hematopoietic cells and endothelial cells |

mouse anti-CD34, Covance Research Products, Berkeley, CA (1:800) |

5 |

| PAL-E | NRP-1 antagonist | fenestrated and leaky vessels |

mouse anti-PAL-E, Abcam, Cambridge, MA (1:200) |

13–16, 43–45 |

| PV-1 | membrane glycoprotein of fenestrate and stomatal diaphragm of caveolae |

fenestrated vessels | rabbit anti-PV-1, Atlas Antibodies, Stockholm, Sweden (1:500) |

11–12 |

| aSMA | actin isoform | SM cells and pericytes |

mouse anti-SMA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO (1:16000) |

17–18 |

| NG2 | transmembrane glycoprotein | pericytes and new blood vessels |

rabbit anti-NG2, Chemicon, Temecula, CA (1:2000) |

8–10 |

| CA IV | membrane enzyme: carbonic anhydrase, pH modulation |

endothelial cells | rabbit anti-CA IV .Kang Zhang, (1:10000) |

17–18, 49 |

| APase | enzyme: hydrolysis | endothelial cells | 19–23 | |

| eNOS | enzyme: NO synthese | endothelial cells | rabbit anti-eNOS, Assay Design Inc., Ann Arbor, MI (1:500) |

24 |

NO=Nitric Oxide; NRP-1=Neuropilin-1; SM=Smooth Muscle

A unique property of mature CC is the presence of fenestrations predominantly on the retinal side of the capillary lumen. Fenestrations had been visualized only at the ultrastructural level but their structure has recently been partially elaborated. PV-1, or PLVAP (plasmalemmal vesicle associated protein), is a glycoprotein in the diaphragms of fenestrae and stomatal diaphragms of caveolae and transendothelial channels in the endothelia of several vascular beds.11, 12 An antibody against PAL-E, the Pathologische Anatomie Leiden-Endothelium, was first reported to recognize fenestrated and leaky blood vessels in diabetic subjects.13–15 Recently, this PAL-E antibody was reported to recognize the antigen neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) in human endothelial cells, a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor.16

The major function of the CC is the transport of nutrients to the RPE and photoreceptors as well as removal of waste from these cells. In general, it maintains the homeostasis in the choroid/RPE/photoreceptor complex. To accomplish this, the endothelial cells of the CC express unique enzymes. CA IV is one of fourteen carbonic anhydrase (CA) isozymes to have been identified in mammals. CA IV is a membrane enzyme that catalyzes the reversible reaction in which CO2 + H2O are converted to HCO3− and H+. When coupled to the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate co-transporter (NBC1), the complex will control local pH.17 Immunohistochemically, CA IV is associated with endothelial cells of adult CC18, however, the expression of this enzyme during development is unknown.

Alkaline phosphatase (APase) is prominently expressed in the choroidal vasculature.19 This enzyme is only expressed in viable choroidal blood vessels and neovascularization has been shown to have most intense APase activity.20, 21 APase hydrolyzes a variety of substrates which generates inorganic phosphate anions and is responsible for vascular calcification and osteogenic differentiation.22, 23 APase activity was demonstrated by enzyme histochemistry in the current study. Another enzyme in CC is endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which is a key to normal circulation in the choroidal vasculature.24 Production of NO by this enzyme, assures proper vasodilation.

One of the final events in maturation of a blood vessel is the investment of a blood vessel by adventitial cells: pericytes around capillaries and venules and smooth muscle cells (SMC) in the walls of arterioles and arteries. Again, little is known regarding the differentiation and appearance of contractile cells associated with the choroidal vasculature during embryonic and fetal development. Alpha SM actin (αSMA) is one of six actin isoforms and is the predominant actin isoform found in SM cells and pericytes.6 Nerve/glial antigen 2, NG2, is a transmembrane proteoglycan that is present in pericytes of new blood vessels during pre- and postnatal development, as well as in tumors, in granulation tissue and in pathological corneal and retinal angiogenesis.8, 9 However, it has also been reported in brain endothelia cells as well.10

The purpose of this study was to investigate the morphological and functional maturation of human fetal CC. Although Ida Mann documented the development of human CC by light microscopy25, our goal was to combine immunohistochemical, enzyme histochemical, and ultrastructural analyses to better understand the structural and functional maturation of this vasculature. Our results suggest that fenestrations were present in substantial numbers only after 21 WG and pericytes were recognizable by 22 WG. Many of the other functional characteristics studied were present very early in embryonic and fetal CC development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Age determination and preparation of human fetal tissue

Fetal human eyes from 7 to 22 WG were included in this study. Tissues were provided by Advanced Bioscience Resources Inc. (Alameda, CA) after aspiration abortions in accordance with the guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval by the Joint Commission for Clinical Research at the Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine. The age of each fetus was determined using last menstruation date and/or ultrasonography and fetal foot length as a reliable indicator of gestation age.26 The eyes were fixed within an hour of harvest in 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, with 5% sucrose at room temperature. The eyes then were washed in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer with 5% sucrose and were shipped overnight at 4°C in the same buffer. For older cryopreserved eyes (≥12 WG), the anterior segments were removed and eye cups were washed in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer with increasing concentration of sucrose: a 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2 mixture of 5% sucrose: 20% sucrose.27 The eyecups were kept at room temperature for 2 hrs in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer with 20% sucrose and then dissected into four blocks, each containing an arcade of retinal blood vessels in 16 WG and older eyes or the two vascular arcades (superotemporal and inferotemporal) and two avascular areas in 12–14 WG eyes (superonasal and inferonasal). The optic nerve head was included in the superotemoral blocks. For younger eyes (≤9 WG), the whole eye were cryopreserved and frozen by the same method. The tissue was infiltrated for 30 min at room temperature and embedded in a solution consisting of a 2:1 mixture of 20% sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate buffer:OCT compound (TissueTek, Baxter Scientific Columbia, MD). The tissues were then frozen in isopentane cooled with dry ice and stored at −80°C. Cross sections 8 µm thick were cut on Microm HM500M cryostat (Global Medical Instrumentation, Ramsey, MI) at −25°C. Cryopreserved tissue from a 73 year-old Caucasian female with no known history of ocular diease (cause of death: colon cancer) was used as a positive control for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry on cryopreserved tissue

Streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (APase) immunohistochemistry was performed on sections of cryopreserved tissue using a nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) system described previously.28 In brief, 8-µm-thick cryopreserved sections were permeablized with absolute methanol and blocked with 2% normal goat serum in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.4) with 1% BSA and then an avidin-biotin complex (ABC) blocking kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). After washing in TBS, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the primary antibodies listed in Table 1 at the stated titer. After washing in TBS, sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies diluted 1:500 (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Finally, sections were incubated with streptavidin APase (1:500, KPL, Gaithersburg, MD), and APase activity was developed with a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl phosphate (BCIP)-NBT kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.), yielding a blue immuno-reaction product.

For assessment of reaction product in choroid and RPE, the melanin pigment was bleached by a technique developed by Bhutto et al28 after streptavidin APase immunohistochemistry. Once bleaching was completed, coverslips were applied with Kaiser’s glycerogel mounting medium without counterstaining.

PAS-Alkaline phosphatase (APase) staining

A previously published PAS/APase staining method was used to identify viable choroidal capillaries (APase activity) and basement membranes.29 The sections were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in APase medium, which included 2 mg napthol AS-MX phosphate and 10 mg fast blue RR salt in 20 ml of a 0.1 M TRIS buffer, pH 9.2, as previously reported19, followed by washing in several changes of distilled water. The sections were then placed into freshly prepared 0.5% periodic acid for 5 min, followed by a brief wash in distilled water. The sections were then treated in Schiff’s reagent for 10 min and developed in several changes of tap water until the water appeared clear. The sections were not bleached, so the RPE melanin is apparent in sections. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Transmission Electronic Microscopy (TEM)

Eyes from 11, 14, 16, and 22 WG fetuses were processed for TEM. Tissue from a 58 year-old Caucasian male with no known history of ocular disease (cause of death: multiple myeloma) was used to demonstrate the ultrastructure of the adult human. Fetal tissue was fixed within one hour of harvest while the adult tissue was fixed at 23 hours postmortem. After primary fixation overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% paraformaldehyde in cacodylate buffer, the tissue was washed in 0.1M phosphate buffer and postfixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.05 M cacodylate buffer for 90 min. After washing in 0.05 M cacodylate buffer, it was dehydrated in 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100% ethanol (ETOH) and then stained with 1% uranyl acetate in 100% ETOH. The tissue was placed in propylene oxide twice for 15 min each time, and then was kept overnight in 1:1 propylene oxide to resin mixture. The tissue was then infiltrated in 100% LX112 resin (Ladd Research Industry, Burlington, VT) for 4–6 hours under vacuum and finally embedded in a final change of 100% LX112 resin and polymerized at 60°C for 36–48 hours. Ultrathin sections were cut with a Leica Ultramicrotome UCT (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and analyzed with a H7600 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

After treating cryosections in absolute methanol for 5 min at −20°C and allowing them to air dry, sections were stained with Harris’ hematoxylin for 20 seconds. After washing in distilled water, the sections were blued in lithium carbonate, rinsed in distilled water, and then stained in 0.5% alcohol Eosin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). After dehydration to xylene, the sections were coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ).

RESULTS

1. Structural maturation

Fenestrations

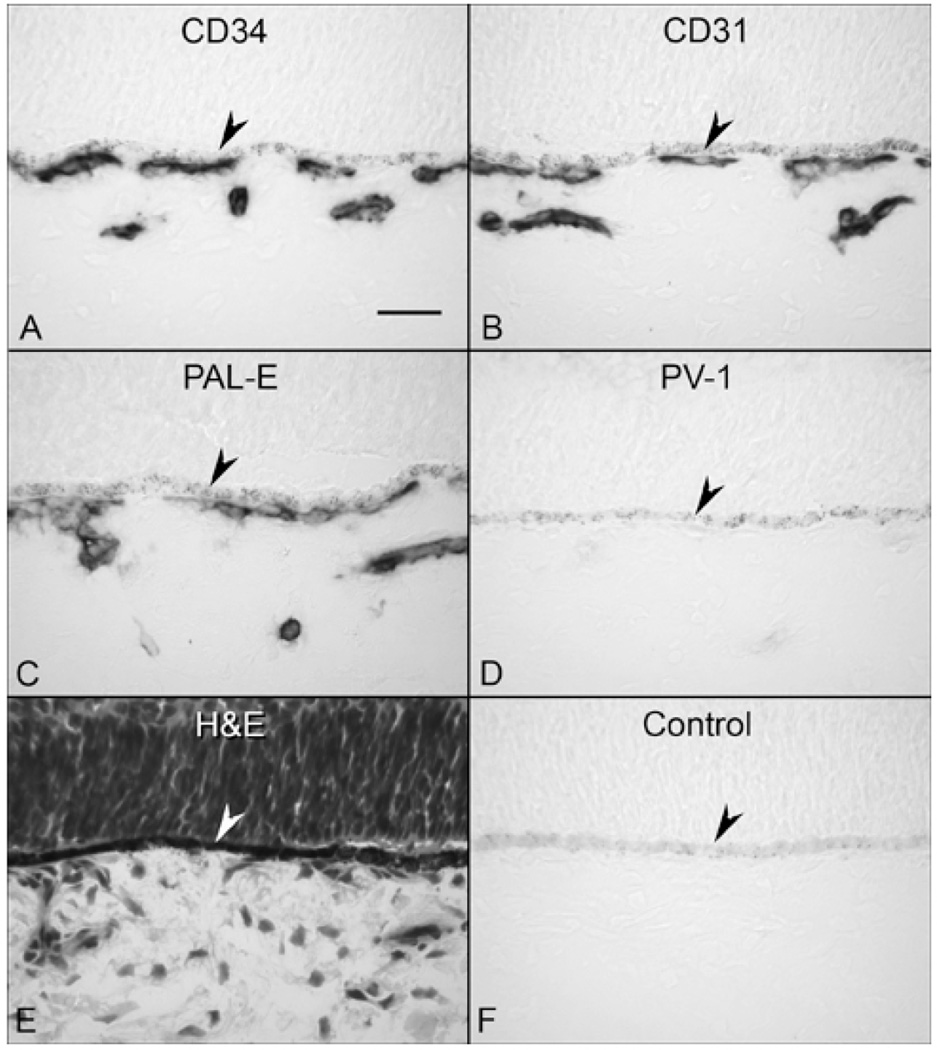

At 7 and 9 WG, one layer of choroidal vasculature was observed demonstrating that the CC, which had prominent CD31, CD34 and PAL-E immunoreactivities (Table 2), develops before any intermediate or large blood vessels have formed, as reported previously.3 PV-1 staining was not observed suggesting that there were no functional fenestrations at this age (results not shown but similar to Figure 1).

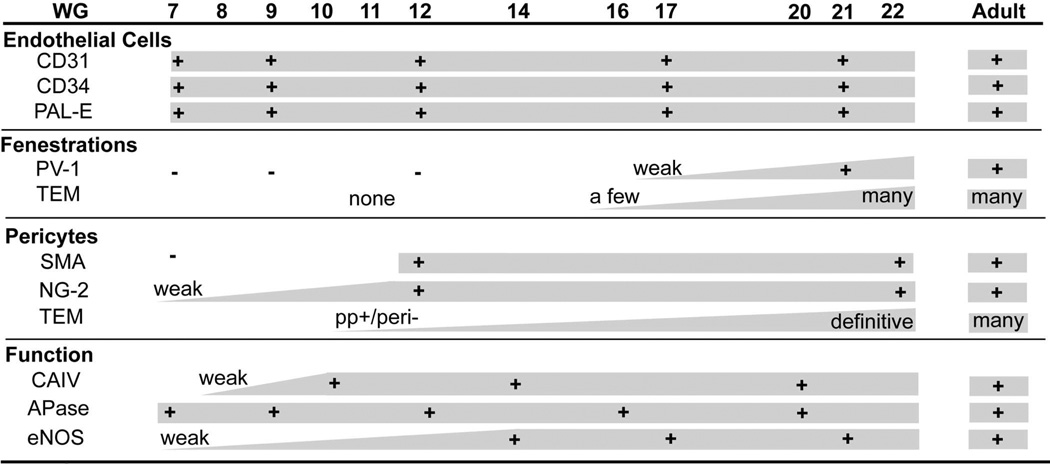

Table 2.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical localization of endothelial cell markers (A–C) and PV-1 (D) in 12 WG choroid. Endothelial cell markers label the choriocapillaris (CC) and developing deeper vessels while no PV-1 immunolabeling is seen. The structure of the choroid is shown with H&E (E) and a nonimmune IgG control for PV-1 is shown in “F”. (arrowhead, RPE; scale bar 30µm; A–D & F, APase immunoreactivity)

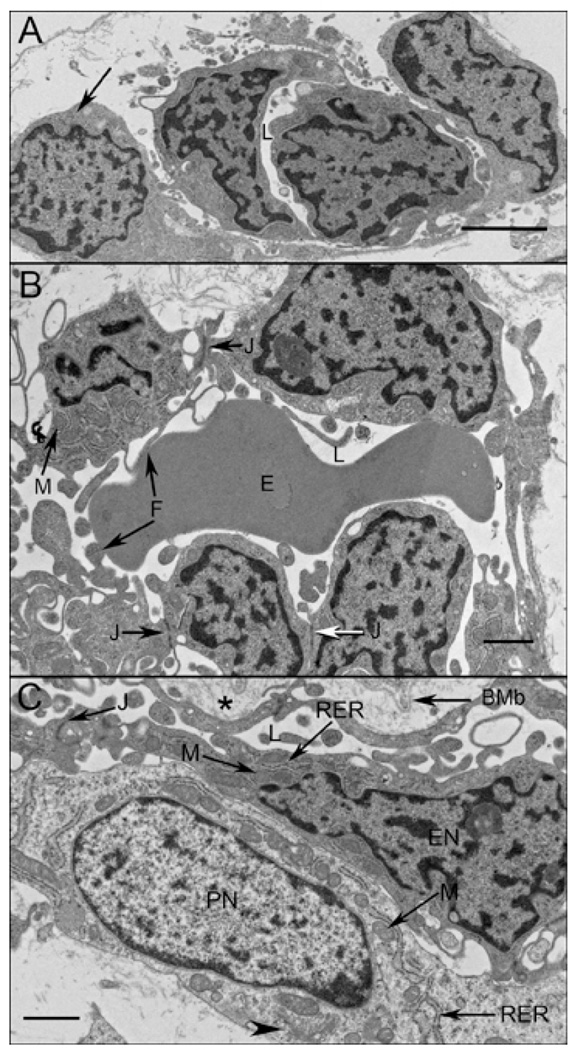

At 11–12 WG, deeper choroidal vessels were observed. Vascular development was more advanced in the posterior pole than in equatorial choroid based on the presence of intermediate size blood vessels. These vessels were positive for the endothelial cell markers including PAL-E but were negative for PV-1 (Figure 1). TEM of the peripheral CC at this age demonstrated primitive aggregates of undifferentiated vascular precursors with irregularly shaped nuclei and dense nuclear chromatin, which formed only slit-like lumens (Figure 2A). It was often difficult to differentiate between the endothelial cells and pericytes in periphery (area from equator to ora serrata) at this age because of their similar ultrastructural features, although some cells appeared to assume a pericyte-like position on the primitive vascular wall (Figure 2A). More definitive pericyte-like cells were found adjacent to more developed vessels in central choroid (area from disc to equator)(Figure 2C). In the more mature central blood vessels, the pericytes had a nucleus that appeared more differentiated and had distinct organelles (golgi, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria), while the endothelial cells still had condensed chromatin and dense cytoplasm (Figure 2C). In both cell types, RER was intimately interwoven between mitochondria in a perinuclear position. Apparent tight junctions were present between the cells. There were some immature red blood cells within the primordial CC lumens (Figure 2B). Within the primitive lumens that had formed, complex membranous infoldings that resembled filopodia projected into the scant luminal space (Figure 2B). In some lumens at the equator that were more open (Figure 2B), the filopodia appeared to touch erythrocytes in the lumen and the plasma membranes of the two cells appeared to be fused. The filopodial projections were also noted outside the lumens. An occasional fenestrae was associated with the filopodia-like structures both in and around the lumen. Basal lamina was not observed around these developing vessels.

Figure 2.

Ultrastructure of CC at 11 WG in periphery (A), equator (B), and posterior pole (C). In peripheral choroid, undifferentiated angioblasts (pericyte and endothelial cell precursors) had dense chromatin and formed loosely arranged aggregates with slit-like lumens (L). One angioblast appears to have assumed the posxition of a pericyte (arrow). Immature endothelial cells at the equator (B) had numerous mitochondria (M) with some tight junctions present (J). Complex membranous infoldings resembling filopodia (arrow F) extended into the developing lumen (F) and when immature erythrocytes (E) were present, their membranes appeared to fuse. In posterior pole (C), pericyte-like cells were observed and appeared more differentiated, with dispersed chromatin in their nuclei (PN) and numerous mitochondria (M) in close proximity with rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and some Golgi (arrowhead). Endothelial cells had condensed chromatin in their nuclei (EN), made tight junctions with one another and displayed some mitochondria (M). Bruch’s membrane (asterisk) was starting to form in the central choroid, posterior to the RPE basement membrane (BMb). (Scale bar in A&B 2 µm and C 1 µm)

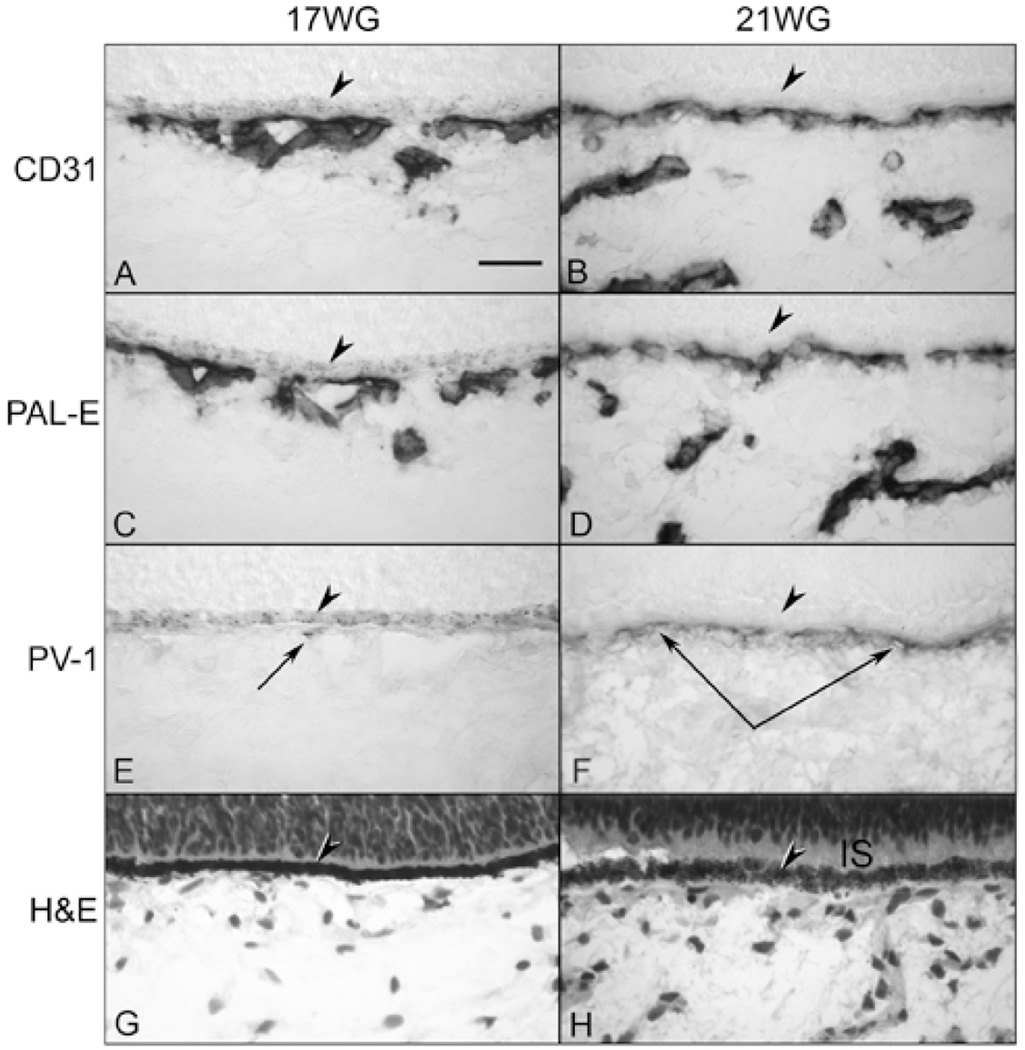

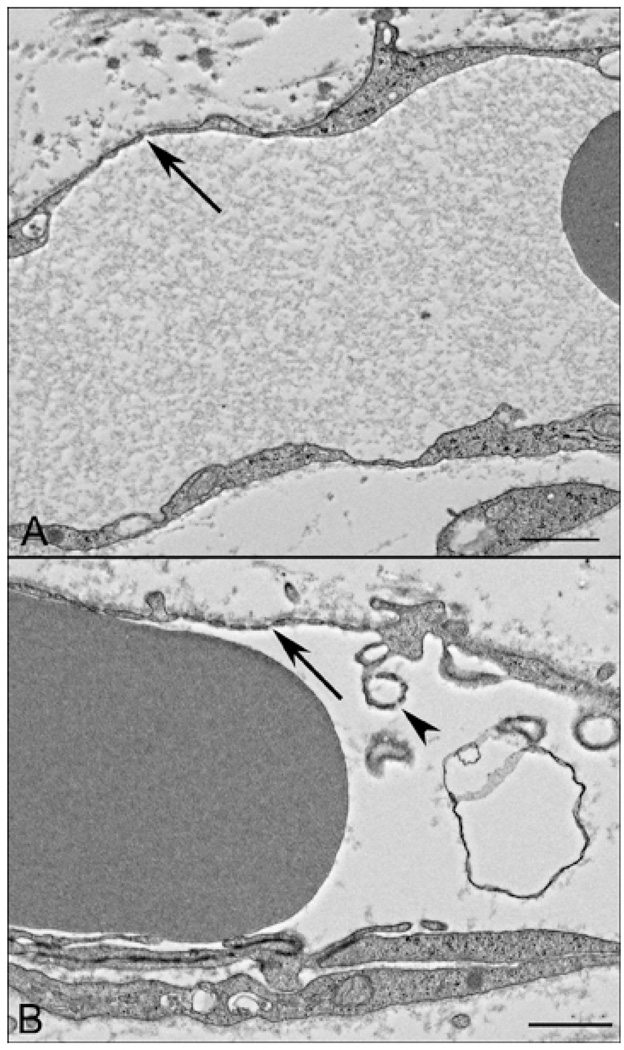

At 16–17 WG, the CC and large choroidal vessels had more intense labeling of endothelial cell markers (Figure 3), especially PAL-E, than in the younger ages. Some areas of CC were weakly positive with PV-1 antibody suggesting the presence of some fenestrations (Figure 3E). TEM confirmed that there were a few fenestrations in the CC at this age but they were scarce and not continuous (Figure 4). The number of fenestrations was greatest in the posterior pole where the CC was most mature morphologically (Figure 4B). Fenestrations in these areas were primarily found on the filopodia within the lumen and occasionally in the wall of more developed vessels. The number of filopodia in these broader lumens appeared greatly increased compared to 11 WG. The endothelial cell nuclei were more oval and uniform in shape with less dense chromatin. The rough endoplasmic reticulum appeared less dispersed. The endothelial junctions were slightly more pronounced and Bruch’s membrane appeared more organized. Basal lamina was present but was more apparent on the retinal side of the blood vessel.

Figure 3.

Comparison of endothelial cell marker localization and PV-1 immunolabeling in 17 WG (A, C, E, G) and 21 WG fetal choroids (B, D, F, H). CD31 (A&B) and PAL-E (C&D) show labeling of both the CC and deeper vessels. Patchy weak PV-1 staining is seen in the 17 WG CC (arrow in “E”) while the reaction product is more intense and uniform in the 21 WG CC (paired arrows in “F”). H&E staining shows the structure of the choroid and RPE (arrowheads in all) with rudimentary inner segments (IS) are present at 21 WG (H). (scale bar = 30µm; A–F, APase immunoreactivity)

Figure 4.

16 WG fetal choroid TEM showing an occasional scattered fenestration (arrow) in the CC endothelium in periphery and more numerous fenestrations in posterior pole (arrow in B). Very few filopodia (arrowhead) are present in the lumen (L) at this age.(scale bar = 1 µm)

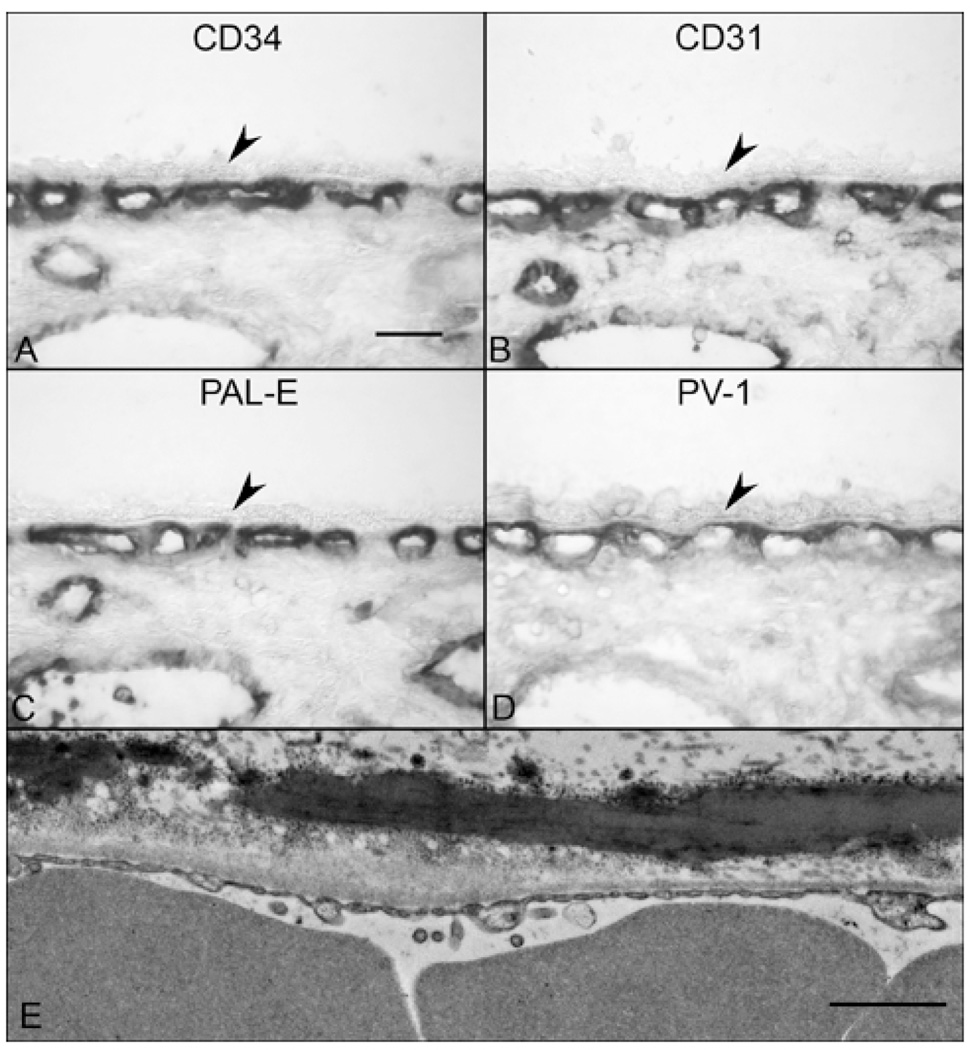

At 21 WG, three layers of blood vessels were apparent within the posterior pole region as demonstrated with endothelial cell markers (Figure 3B,D). This is the first time point at which there is morphological evidence of photoreceptor differentiation. Short rudimentary inner segments were present posterior to the neuroblastic layer (Figure 3H). PV-1 immunoreactivity was present in most of the CC (Figure 3F) but again it was more intense in the posterior pole than in periphery. TEM at 22 WG demonstrated that the CC was now thin-walled, flat blood vessels with open lumens and contiguous areas of fenestrations (Figure 5). Well-formed tight junctions with defined zonulae were present. There were still a few membranous infoldings present in the lumens and the basement membrane of the endothelial cells was more prominent and continuous but very thin compared to the adult human CC (compare Figure 5 and 6). In the adult human eye used as a positive control, the PV-1 was uniformly intense and more apparent on the retinal side of the CC lumens, while the other endothelial cell markers (CD31, CD34, and PAL-E) were uniform around the CC lumens (Figure 6). Although the literature suggests fenestrations are only on the retinal side of the CC, we observed some fenestrations in the adult choroid on the scleral side, but the number was greatly reduced compared to the retinal side, which is also suggested by the PV-1 localization in the adult (Figure 6D).

Figure 5.

TEM of a 22 WG fetal choroid showing scattered fenestrations (arrow) in the CC endothelium in periphery (arrow in A) and more numerous fenestrations in posterior pole (arrow in B). Membranous infoldings were fewer and sometimes had fenestration-like structures (arrowhead). (scale bar = 1 µm)

Figure 6.

Comparison of endothelial cell marker staining and PV-1 immunolabeling in 73-yr-old. CD34 (A), CD31 (B) and PAL-E (C) show labeling of both the CC and larger vessels while PV-1 is restricted to the CC and most intense on the retinal side of CC (D).(arrowheads = RPE, scale bar = 30 µm) (E) TEM from a 58 yr-old shows contiguous fenestrations in the inner CC wall. (Scale bar = 1 µm)

Investment of Blood Vessels with Pericytes and Smooth Muscle Cells

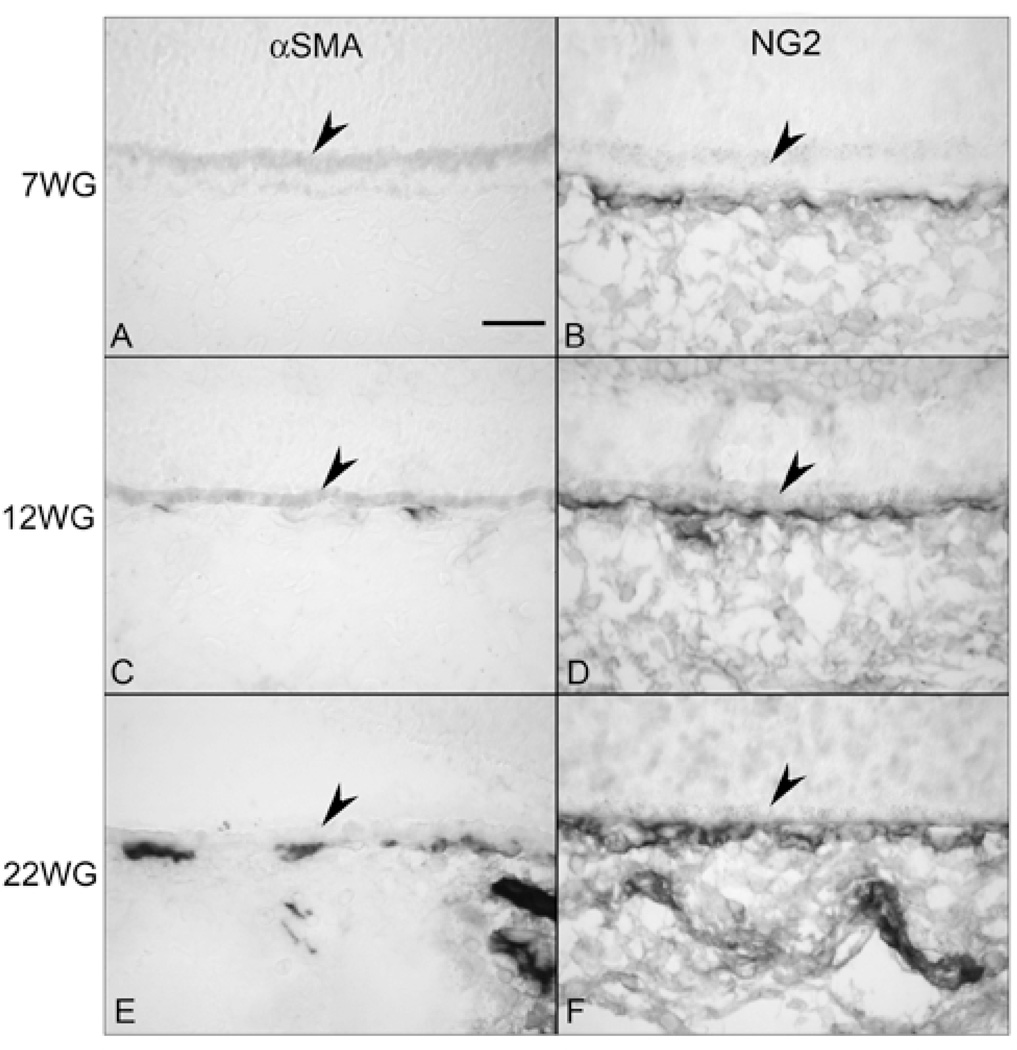

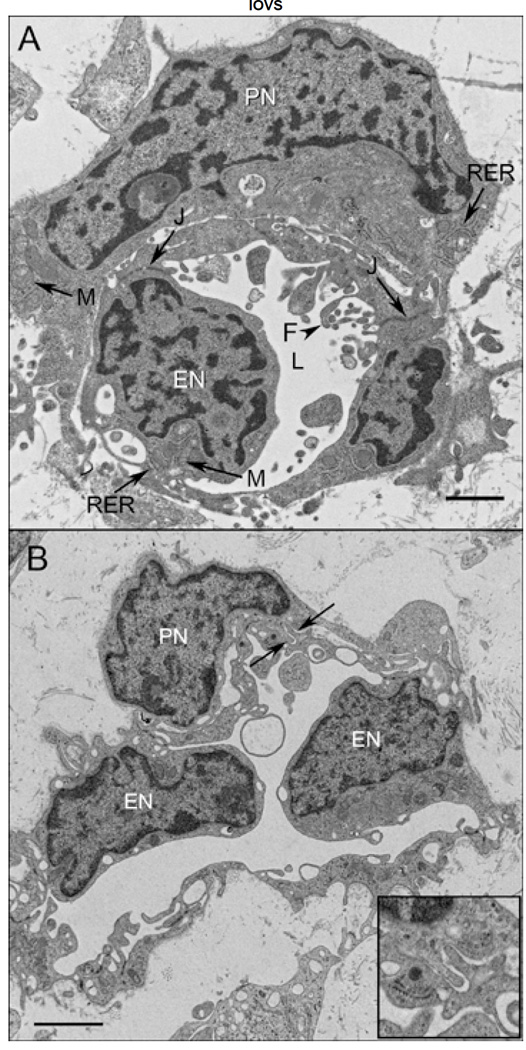

At 7 WG, there were no αSMA positive cells in choroid (Figure 7A). At 12 WG, some areas of CC were positive for αSMA (Figure 7C). These areas may coincide with the very immature cells observed by TEM, that appeared to occupy a pericyte-like position on the abluminal face of the blood vessel wall (Figure 8A). At 14 WG in peripheral CC, cells in the abluminal position of a pericyte formed peg-in-socket like contacts with endothelial cells lining the lumen (Figure 8B). Both cell types still appeared undifferentiated in that their nuclei were bulky with condensed chromatin, the cytoplasm was filled with vesicles, and mitochondria were surrounded by rough ER. Alpha SMA immunoreactivity increased continuously with age until 22 WG when αSMA+ cells were present throughout the CC and also around intermediate and large choroidal blood vessels (Figure 7E). TEM demonstrated that definitive pericytes were present around CC at this age (Figure 9). Their nuclei were oval and had homogenous chromatin, while their cytoplasmic processes were thin and alligned with the endothelial cell processes (Figure 9). NG2 is said to be a pericyte marker as well. However, the developing CC at 7 WG had some NG2 immunoreactivity (Figure 7B) even though no definitive pericytes were present by TEM until 22 WG (Figure 8A) (Table 2). NG2 immuno reaction product was very prominent at 12 and 22 WG when pericytes were more apparent by TEM.

Figure 7.

Smooth muscle actin (αSMA) (A, C &E) and NG2 immunostaining (B, D &F) in choroid at 7 (A,B), 12 (C,D) and 22 WG (E,F). At 7 WG, no immunoreactivity for αSMA (A) was observed but NG2 (B) labeled cells were associated with the CC. At 12 WG, some scattered αSMA positive cells (C) were associated with CC and NG2 staining (D) was more intense. By 22 WG, αSMA immunoreactivity (E) was associated with CC, medium and large choroidal vessels. NG2 also intensely immunolabeled all vessels but the pattern was more uniform and similar to the pattern observed with endothelial cell markers (Figure 3B).(Scale bar = 30 µm)

Figure 8.

Maturation of pericytes in CC. At 11 WG (A), poorly differentiated pericytes (PN) were associated with immature endothelial cells in peripheral choroid. The nuclei were irregularly shaped and had condensed chromatin. The cell cytoplasm contained rough endoplasmic reticulae (RER) and mitochrondria (M). Junctions (J) were present between endothelial cells (EN) and the developing lumen contained numerous endothelial cell projections. No basement membrane was apparent around the pericyte or endothelial cells. (B) A capillary from peripheral choroid at 14 WG. The pericyte was more compact and its processes form peg-in-socket formations with endothelial cell processes (double arrow in “B” shown at higher magnification in inset). There are many vesicles present in the endothelial cell processes. Both the pericyte and endothelial cell nuclei (EN) have condensed chromatin but this forming vessel had a more open lumen than at 11 WG. (Scale bar 2 mm)

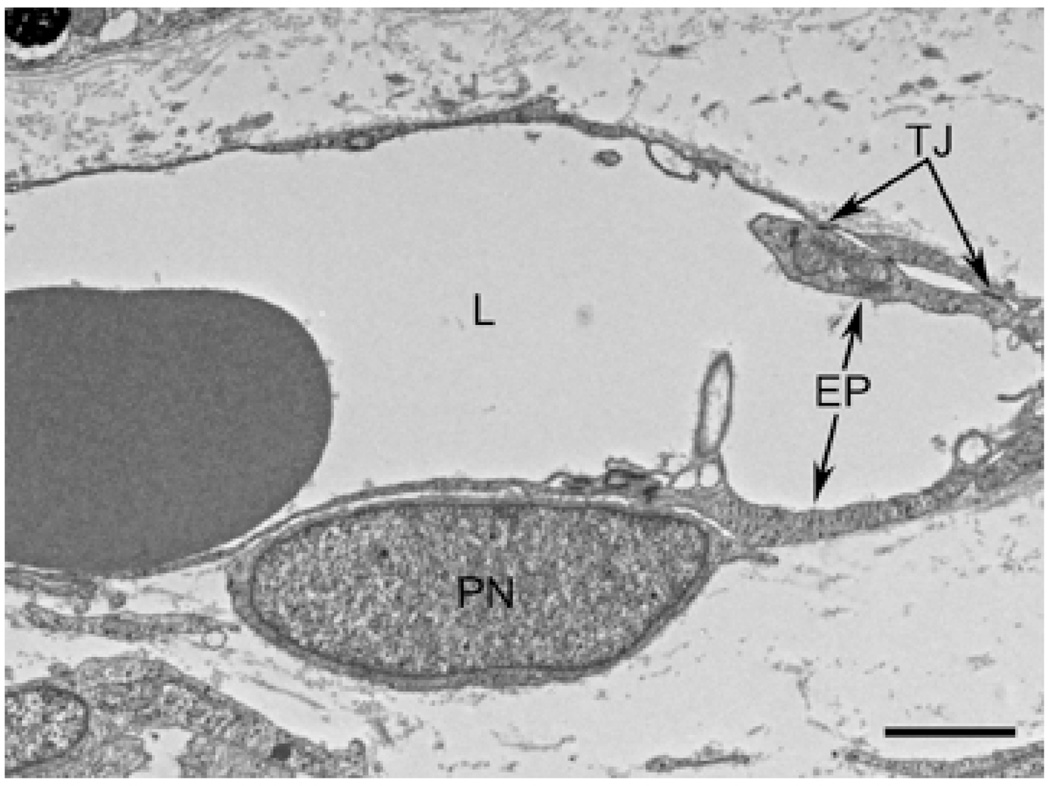

Figure 9.

At 22 WG, capillary walls were much thinner, tight junctions (TJ) were obvious, and basement membrane was being formed but still was limited. A pericyte was well developed (PN) and clearly abluminal but in close contact with endothelial cell processes (EP). (Scale bar in A 1 µm and B 2 µm)

2. Functional maturation

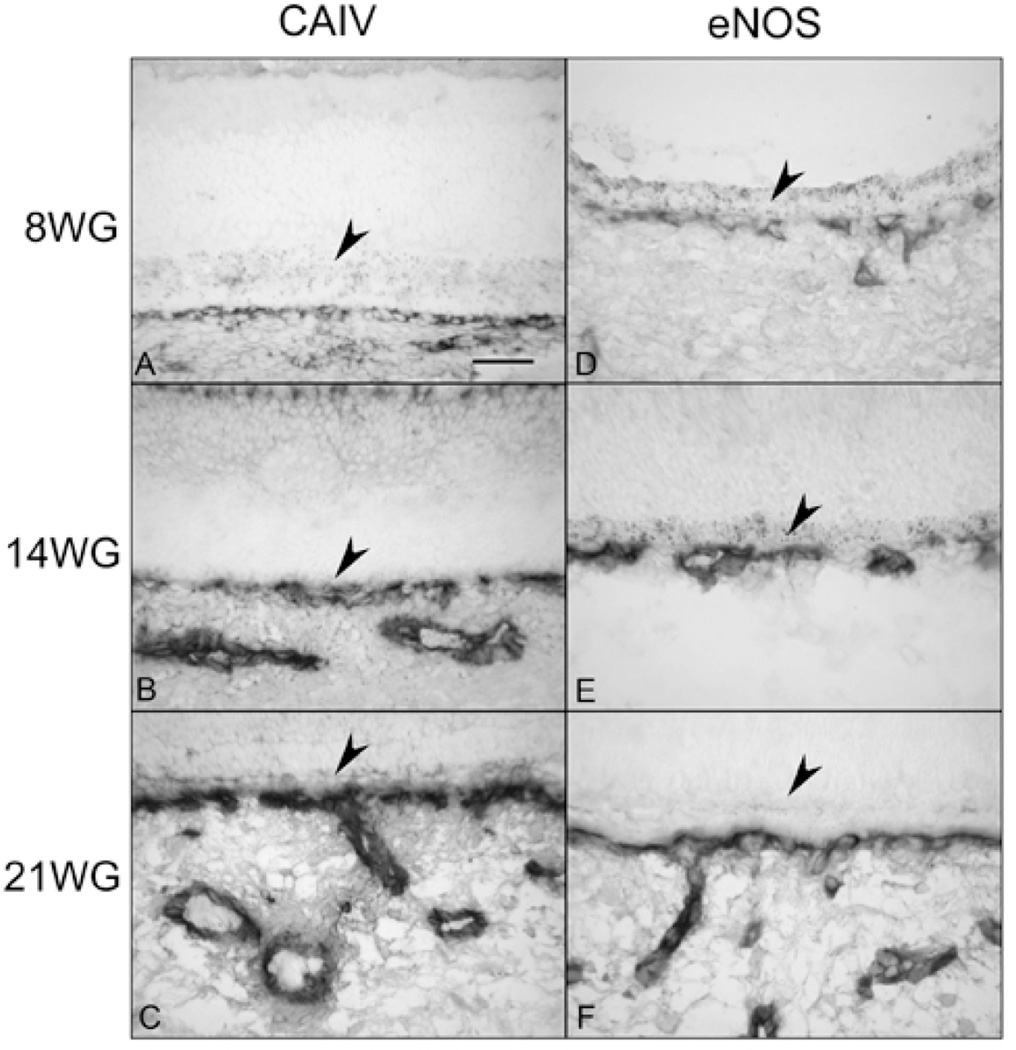

It has been reported that carbonic anhydrase IV (CA IV) is specific for the CC. As early as 8 WG, very weak CA IV reaction was observed in CC even though it was just forming by hemo-vasculogenesis (Figure 10A). At 14 WG, large choroidal vessels and CC had prominent CA IV immunoreactivity (Figure 10B) and at 21 WG, all three layers of choroidal vasculature had CA IV immunoreactivity (Figure 10C). Of particular interest was that CA IV was present in retinal blood vessels in the developing fetal eye (data not shown). This was not the case in the adult eye.

Figure 10.

Carbonic anhydrase IV (CA IV)(A, B, C) and eNOS (D, E, F) immunolocalization in 8 (A, D), 14 (B, E) and 21 WG choroid (C, F). Forming CC shows weak staining for CA IV and eNOS at 8 WG that increases with age with all choroidal vessels showing prominent immunoreactivity at 21 WG. (arrowhead, RPE). (Scale bar 50 µm; APase immunohistochemical reaction product in all)

During hemo-vasculogenesis (7–9 WG), eNOS was expressed at low levels in developing blood vessels (Figure 10D). By 14 WG, when lumens were apparent, intense eNOS immunoreactivity was observed in the CC (Figure 10E) and this high level was present in all choroidal vessels at 21 WG (Figure 10F).

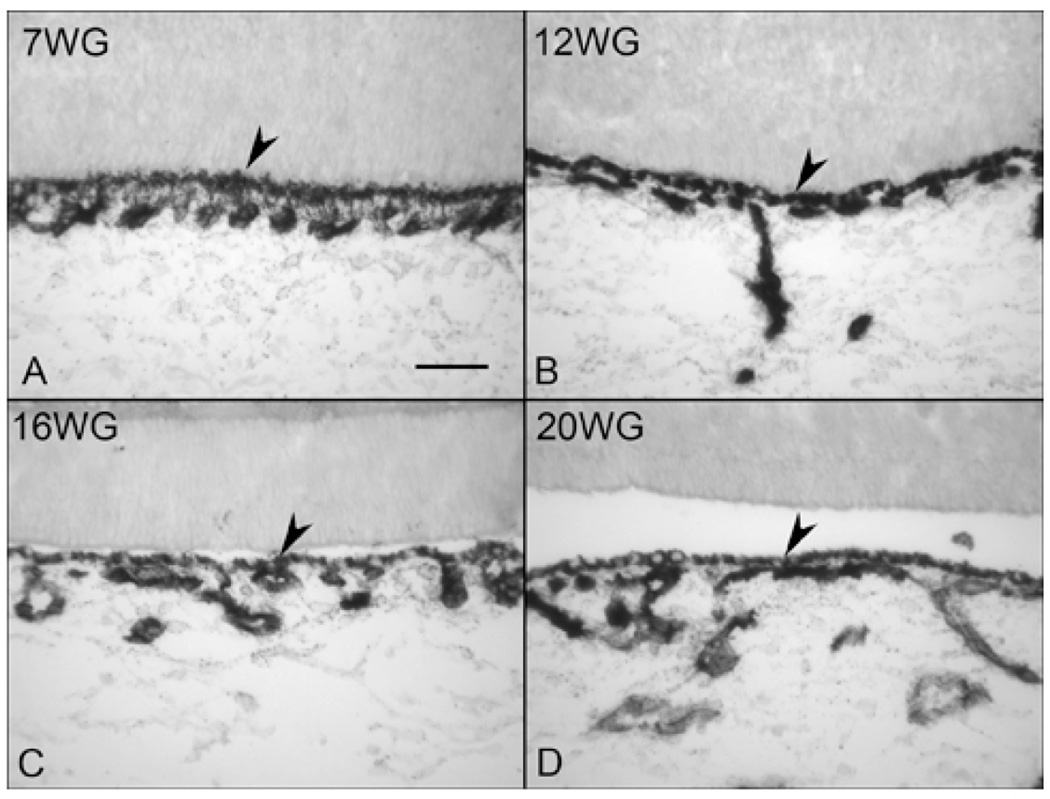

We have used alkaline phosphatase enzyme histochemistry (APase) extensively as a marker for CC. In the adult, all choroidal vessels express APase but arteries have the least intense reaction product.19 At 7 WG, forming CC already had APase activity even though the primitive endothelial cells were just starting to differentiate from hemangioblasts (Figure 11A).3 The APase+ vascular structures were not cord-like but rather like islands or aggregates of cells, as would be expected during hemo-vasculogenesis. At 12 (Figure 11B) and 16 WG (Figure 11C), the CC and intermediate blood vessels had APase activity. At 20 WG, all three layers of choroidal vasculature expressed APase. The limited PAS staining suggests that neither Bruch’s membrane nor capillary basement membranes were completely formed as confirmed by TEM.

Figure 11.

Enzyme histochemistry for alkaline phosphatase (APase) and counterstaining with PAS. At 7 WG, forming CC already had APase activity (A). At 12 WG, the CC and intermediate connecting vessel had APase activity (B). At 16 WG, two layers of choroidal vessels showed APase activity (C). At 20 WG, all three layers of choroidal vasculature had APase activity (D). The limited PAS staining suggests that neither Bruch’s membrane nor capillary basement membranes were completely formed. (arrowhead, unbleached RPE).(Scale bar 50 µm)

Discussion

The CC is responsible for supplying nutrients and oxygen to the photoreceptors. The photoreceptors consume more oxygen per gram of tissue than any other cell type in the body. Therefore, the photoreceptors require their own and somewhat unique vasculature, the choriocapillaris. The development of this vasculature has only recently been elaborated by our lab.3 From 6 through 8 WG, a process recently called hemo-vasculogenesis occurs, which involves the differentiation of blood vessels and blood cells from a common precursor, the hemangioblast.3 In the current study, we documented the functional and structural maturation of this unique, lobular capillary network from the primitive vessels that formed by hemo-vasculogenesis to the large flat, thin-walled, fenestrated vessels that service the photoreceptors in adult life (summarized in Table 2).

One striking feature of choroidal hemo-vasculogenesis was that the islands of precursors expressed CD31, CD34, CD39, VEGFR-2, vWf, as well as Hbε as early as 6 WG.3 The earliest time point examined in the current study was 7–8 WG when all of the above markers were still present but fenestrations (PV-1) have not yet formed. Even at 11 WG, TEM demonstrated that both luminal and perivascular cells had similar ultrastructural characteristics including condensed chromatin in large round nuclei, reminiscent of mesenchymal precursors. This suggests that both cell types differentiate from common precursors, which has been demonstrated to occur in vitro with vascular precursors by our lab and others.30, 31 At 11 WG, very little αSMA was expressed, which is a marker for mature pericytes, so the often-seen adventitial cells probably were not completely differentiated into pericytes. It is interesting that NG2, another pericyte marker, was actually present at low levels at the completion of hemo-vasculogenesis (9 WG). This is not surprising though because we find NG2 present on some endothelial cells in retinal and choroidal neovascularization so, in our experience, it is not exclusively a pericyte marker (D.S. McLeod and G.A. Lutty, unpublished data 2005). Levine and Nishiyama found NG2 associated with glial precursors, chondroblasts, brain endothelial cells, skeletal myoblasts and human melanoma cells.32 Another possibility is that NG2 is made very early in pericyte differentiation, i.e. before they have the ultrastructural characteristics of pericytes (Figure 2). The expression of αSMA seems to represent maturation of these cells because TEM at 22 WG confirms that morphologically some mature pericytes were present: they no longer had condensed chromatin, they were ensheathing the blood vessels, and had a more traditional flattened, oval profile in central choroid.

Lumen formation is a key event in blood vessel maturation. As just mentioned, the initial luminal spaces were slit-like clefts and the cells lining them appeared as rotund mesenchymal precursors. Sellheyer observed the slit-like lumens as early as 6.5 weeks gestation33 when we have demonstrated that hemo-vasculogenesis is occurring.3 Even at this stage, the cells made recognizable tight junctions that are necessary for a mature vasculature. This also suggests that these luminal cells are committed to being endothelial cells. There are currently thought to be two steps in capillary formation: formation of solid cords and then lumen formation34, which have been documented in developing human retina.35, 36 However, the more mature open lumens at 11 WG (Figure 8) are more reminiscent of the open central cavity that is observed in the embryoid bodies as they attempt to make lumens, and in yolk sac when the initial vessels form. This seems logical because the CC has formed without blood flow by hemo-vasculogenesis, which occurs in yolk sac in vivo and embryoid bodies in vitro. It is not until 22 WG that the lumens are broad and flat as observed in the mature CC. At this time point, the endothelial cells are fusiform, the wall of the blood vessel is thin and pericytes have assumed a flatter profile and ensheath the blood vessels with their processes. This is also the time when photoreceptors develop inner segments (Figure 3)37 and their metabolism is increased.

Another striking characteristic of the immature lumens at 11 WG, are the extensive, membranous processes that were present within the luminal space. These processes resembled filopodia, which are present on tip cells, cells leading the vanguard of a forming blood vessel in retinal vascular development. They sense the milieu and are critical in determining the direction that a vessel will take and in motility of endothelial cells.38 In the CC, however, they extended into the lumens. What they are sensing in the lumen or whether they are sensing is unclear, because this vasculature does not appear to have directional growth and migration into lumen is unlikely. The new vessels appear to be present where the island of precursors were and emanate from the initial island to make a lobule.3 Roy and associates observed cytoplasmic extensions from developing endothelial cells in chick brain and called them microvilli.39 In their study as well as ours, the number of cytoplasmic extensions decreased as the lumens became broader. Luminal cytoplasmic extensions have also been observed recently by Maina in chick lung blood vessel development.40 Maina called them filopodia and suggested that endothelial cells and angioblasts used these processes to touch and interlock with each other. They observed that the filopodia from angioblasts interacted with erythroblasts, which we also observed, and the cytoplasmic membrane of the two cells appeared to merge and disappear (Figure 2B).

The choroidal vasculature is one of the few fenestrated capillary beds in the body. Fenestrations are unique pore-like structures that have a diaphragm. They allow passive transit of some fluids and macromolecules, which is critical in their providing outer retina, including retinal pigment epithelium, with nutrients, ions, and oxygen as well as transport of the waste from the RPE out of the eye. They were first observed by electron microscopy41 but recently an integral membrane glycoprotein of ~ 50kD (PV-1) from fenestrations has been purified, cloned, and antibodies made against it.11 The PV-1 antibody recognizes specifically the diaphragms of the fenestrae and stomatal diaphragms of caveolae and transendothelial channels of vascular beds.12 This is the first report of PV-1 antibody in human CC where we observed it clearly in fenestrations of CC. We found no PV-1 immunoreactivity at 9 and 12 WG and observed very few fenestrations at 11 WG by electron microscopy. The few fenestration-like structures observed were mostly present in filopodia within lumens, not a position to serve as a pore between luminal and extraluminal spaces. Sellheyer and Spitznas observed these atypical fenestrations occasionally at 6.5 WG, calling them luminal flaps.42 There was weak immuno reactivity for PV-1 at 17 WG and, in the ultrastructural study, fenestrations were sparse at 16 WG and were observed on both retinal and scleral sides of the lumen (Table 2). They were even observed in the few filopodia that still were present within the lumens, suggesting that these filopodia were simply cytoplasmic membrane extensions without any functional significance. At 21 WG, the PV-1 immunoreactivity was greatly increased in CC and TEM at 22 WG showed continuous fenestrations in some areas. It is noteworthy that the lumens at 22 WG were broad, the walls of the vessels were very thin, and it was in the thinnest areas facing the RPE where the greatest number of fenestrations were present. This is the same scenario as in the adult CC where most fenestrations and the greatest PV-1 immunoreactivity were observed towards the RPE side. Structurally, the endothelial cell lining must be thin since the fenestration pore is only 60–70 nm long.41

Finally, PAL-E was included in this study because it was reported to be present only in fenestrated and leaky blood vessels.14 Later, in diabetic subjects, PAL-E antibody was used as a marker for leaking vessels.13, 43–45 In those studies, retinal microvessels with an intact blood-retinal barrier had no PAL-E staining. On the other hand, advanced diabetic eyes had PAL-E positive retinal vessels and they speculated that this correlated with plasma protein leakage. In our study, not only CC but all other vessels at all fetal ages studied including the adult control subject had strong PAL-E immunoreactivity. The antibody PAL-E is not a fenestrated or leaking vessel marker in our experience.

The current study also investigated the functionality of developing CC. We included three enzymes that are present in adult CC, which are responsible for the diverse activities that the CC performs. APase was present at all time points, so even progenitors appear to express this enzyme. Why calcium transport and processing, the presumed roles of APase, are necessary at this early stage in endothelial cell differentiation is not known. APase is considered a marker for osteoblasts and their precursors46 but has also been observed in pluripotent stem cells47, 48, so its expression early in CC seems logical. CA IV immunoreactivity was present in CC at low levels at 8 WG but was prominent at 10 WG and thereafter (Figure 10). CA IV in CC is coupled with the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate co-transporter 1 (NBC1) to make the bicarbonate transport metabolon which participates in the transport of HCO3− between the CC and RPE, a function thought to be critical for pH modulation in the RPE/photoreceptor complex.18, 49 Photoreceptor metabolism generates acid, so loss of function in CA IV results in an acidic environment and photoreceptor degeneration.49 Since the photoreceptors have not formed inner segments as yet where most mitochondria are present, the importance of the enzyme at this time must concern the relationship between CC and RPE cells. This reactivity of CA IV seemed to represent functional maturity of fetal CC. eNOS is the third enzyme that we studied and its expression was also related to maturity. eNOS expression was not substantial until 14 WG. Its expression may be related to the expansion of the CC lumen to their broad flat final disposition during maturation. Thus, in fetal eyes, functional maturity occurred in advance of structural maturity (Table 2) and this might correlate with the contributions of CC in formation and maturation of the intermediate and large deeper choroidal vasculature.

The initial development of the CC by hemo-vasculogenesis probably bestows certain unique developmental characteristics. Morphologically, it appears that the progenitors differentiate into either endothelial cells or pericytes, although this needs to be further demonstrated with immunohistochemistry for cell markers. Formation of capillaries from islands of progenitors may contribute to formation of the lobular pattern of CC. The final mature CC is very similar to the capillaries of kidney glomeruli: large flat, fenestrated capillaries that are lobular in pattern.50 Like kidney, the capillaries form before development of large and intermediate blood vessels. Lumen maturation from slit-like to broad flat lumens may cause stretching of the vascular segments into a thin wall with single endothelial cell processes. This is most pronounced on the retinal side and is the site where continuous fenestrations will form. On the other hand, the pericyte somas were found on the scleral side. It is interesting that the three enzymes chosen to represent characteristics of a functional CC appear to precede the structural maturation (Table 2). The structural maturation almost coincides with connection to the intermediate and deep vessels, i.e, when blood flow and serum proteins are present. Fenestrations form late in maturation (21–22 WG), which nicely anticipates the differentiation of photoreceptors that Hendrickson and co-workers have shown begins around 24–26 WG when inner segments form.37 After this time, the CC will be sided, fenestrated mostly on the RPE side, which is critical for its adult function in supporting the viability of photoreceptors and RPE cells.

During hemo-vasculogenesis (6–9 weeks gestation, WG), when human choriocapillaris endothelial cell precursors still express markers like epsilon hemoglobin, they appear to assume a luminal position in forming the choriocapillaris wall and make tight junctions. However, formation of continuous fenestrations on the retinal side of the choriocapillaris and broad open lumens do not occur until 21 WG. Likewise, pericyte precursors assume an abluminal position on the wall early in development but do not appear structurally mature (TEM and alpha smooth muscle actin expression) until 21 WG. Overall, the functional maturation assessed occurs well in advance of structural maturation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH-EY-016151 (G.L.), EY-01765 (Wilmer), the Altsheler-Durell Foundation, and a gift from the Himmelfarb Family Foundation. Takayuki Baba was a Bausch and Lomb Japan Vitreoretinal Research Fellow, and an Uehara Memorial Foundation Research Fellow. The authors thank Kang Zang, M.D., Ph.D. for providing the CA IV antibody.

References

- 1.Bhutto IA, Lutty GA. The vasculature of choroid. In: Shepro D, D’Amore P, editors. Encyclopedia of Microvasculatures. New York: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaauwgeers HG, Holtkamp GM, Rutten H, et al. Polarized vascular endothelial growth factor secretion by human retinal pigment epithelium and localization of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors on the inner choriocapillaris. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;155:421–428. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65138-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa T, McLeod DS, Bhutto IA, et al. The embryonic human choriocapillaris develops by hemo-vasculogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2089–2100. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Down-regulation of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 results in thrombospondin-1 expression and concerted regulation of endothelial cell phenotype. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:701–713. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Civin CI, Strauss LC, Brovall C, Fackler MJ, Schwartz JF, Shaper JH. Antigenic analysis of hematopoiesis. III. A hematopoietic progenitor cell surface antigen defined by a monoclonal antibody raised against KG-1a cells. J Immunol. 1984;133:157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herman IM. Actin isoforms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(05)80007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomasek JJ, Haaksma CJ, Schwartz RJ, et al. Deletion of smooth muscle alpha-actin alters blood-retina barrier permeability and retinal function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2693–2700. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozerdem U, Grako KA, Dahlin-Huppe K, Monosov E, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan is expressed exclusively by mural cells during vascular morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:218–227. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozerdem U, Monosov E, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan expression by pericytes in pathological microvasculature. Microvasc Res. 2002;63:129–134. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandrine P, Alexandre P, Manon B, Andre O, Jack A. NG2 immunoreactivity on human brain endothelial cells. Acta Neuropathologica. 2001;102:313–320. doi: 10.1007/s004010000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stan RV, Ghitescu L, Jacobson BS, Palade GE. Isolation, cloning, and localization of rat PV-1, a novel endothelial caveolar protein. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1189–1198. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stan RV, Kubitza M, Palade GE. PV-1 is a component of the fenestral and stomatal diaphragms in fenestrated endothelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13203–13207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes JM, Brink A, Witmer AN, Hanraads-de Riemer M, Klaassen I, Schlingemann RO. Vascular leucocyte adhesion molecules unaltered in the human retina in diabetes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:566–572. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlingemann RO, Dingjan GM, Emeis JJ, Blok J, Warnaar SO, Ruiter DJ. Monoclonal antibody PAL-E specific for endothelium. Lab Invest. 1985;52:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlingemann RO, Hofman P, Anderson L, Troost D, van der Gaag R. Vascular expression of endothelial antigen PAL-E indicates absence of blood-ocular barriers in the normal eye. Ophthalmic Res. 1997;29:130–138. doi: 10.1159/000268007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaalouk DE, Ozawa MG, Sun J, et al. The original Pathologische Anatomie Leiden-Endothelium monoclonal antibody recognizes a vascular endothelial growth factor binding site within neuropilin-1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9623–9629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srere PA. Complexes of sequential metabolic enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:89–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hageman GS, Zhu XL, Waheed A, Sly WS. Localization of carbonic anhydrase IV in a specific capillary bed of the human eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2716–2720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeod DS, Lutty GA. High-resolution histologic analysis of the human choroidal vasculature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3799–3811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukushima I, McLeod DS, Lutty GA. Intrachoroidal microvascular abnormality: a previously unrecognized form of choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:473–487. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLeod DS, Taomoto M, Otsuji T, Green WR, Sunness JS, Lutty GA. Quantifying changes in RPE and choroidal vasculature in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1986–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Q, Kang Q, Si W, et al. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is regulated by Wnt and bone morphogenetic proteins signaling in osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55958–55968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McComb R, Bowers G, Jr, Posen S. Alkaline Phospatase. New York: Plenum Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toda N, Nakanishi-Toda M. Nitric oxide: ocular blood flow, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:205–238. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann IC. The Development of the Human Eye. Cambridge: University Press; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mhaskar R, Agarwal N, Takkar D, Buckshee K, Anandalakshmi, Deorari A. Fetal foot length--a new parameter for assessment of gestational age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1989;29:35–38. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(89)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutty GA, Merges C, Threlkeld AB, Crone S, McLeod DS. Heterogeneity in localization of isoforms of TGF-beta in human retina, vitreous, and choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:477–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhutto IA, Kim SY, McLeod DS, et al. Localization of collagen XVIII and the endostatin portion of collagen XVIII in aged human control eyes and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1544–1552. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao J, McLeod S, Merges CA, Lutty GA. Choriocapillaris degeneration and related pathologic changes in human diabetic eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:589–597. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutty GA, Merges C, Grebe R, McLeod D. Canine retinal angioblasts are multipotent. Exp. Eye Res. 2005;83:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamashita J, Itoh H, Hirashima M, et al. Flk1-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells serve as vascular progenitors. Nature. 2000;408:92–96. doi: 10.1038/35040568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine JM, Nishiyama A. The NG2 chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan: a multifunctional proteoglycan associated with immature cells. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1996;3:245–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sellheyer K. Development of the choroid and related structures. Eye. 1990;4:255–261. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker LH, Schmidt M, Jin SW, et al. The endothelial-cell-derived secreted factor Egfl7 regulates vascular tube formation. Nature. 2004;428:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nature02416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan-Ling T, McLeod DS, Hughes S, et al. Astrocyte-endothelial cell relationships during human retinal vascular development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2020–2032. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasegawa T, McLeod DS, Prow T, Merges C, Grebe R, Lutty GA. Vascular precursors in developing human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2178–2192. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hendrickson AE, Yuodelis C. The morphological development of the human fovea. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:603–612. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerhardt H, Ruhrberg C, Abramsson A, Fujisawa H, Shima D, Betsholtz C. Neuropilin-1 is required for endothelial tip cell guidance in the developing central nervous system. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:503–509. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy S, Hirano A, Kochen JA, Zimmerman HM. The fine structure of cerebral blood vessels in chick embryo. Acta Neuropathol. 1974;30:277–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00697010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maina JN. Systematic analysis of hematopietic, vasculogenic, and angiogenic phases in the developing embryonic avian lung, Gallus gallus variant domesticus. Tissue and cell. 2004;36:307–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhodin JA. Ultrastructure of mammalian venous capillaries, venules, and small collecting veins. J Ultrastruct Res. 1968;25:452–500. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(68)80098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sellheyer K, Spitznas M. The fine structure of the developing human choriocapillaris during the first trimester. Graefe Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988;226:65–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02172721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuiper EJ, Witmer AN, Klaassen I, Oliver N, Goldschmeding R, Schlingemann RO. Differential expression of connective tissue growth factor in microglia and pericytes in the human diabetic retina. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1082–1087. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.032045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlingemann RO, Hofman P, Vrensen GF, Blaauwgeers HG. Increased expression of endothelial antigen PAL-E in human diabetic retinopathy correlates with microvascular leakage. Diabetologia. 1999;42:596–602. doi: 10.1007/s001250051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witmer AN, van den Born J, Vrensen GF, Schlingemann RO. Vascular localization of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in retinas of patients with diabetes mellitus and in VEGF-induced retinopathy using domain-specific antibodies. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:190–197. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.3.190.5519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penolazzi L, Lambertini E, Tavanti E, et al. Evaluation of chemokine and cytokine profiles in osteoblast progenitors from umbilical cord blood stem cells by BIO-PLEX technology. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito S, Liu B, Yokoyama K. Animal embryonic stem (ES) cells: self-renewal, pluripotency, transgenesis and nuclear transfer. Hum Cell. 2004;17:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2004.tb00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito S, Yokoyama K, Tamagawa T, Ishiwata I. Derivation and induction of the differentiation of animal ES cells as well as human pluripotent stem cells derived from fetal membrane. Hum Cell. 2005;18:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2005.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z, Alvarez BV, Chakarova C, et al. Mutant carbonic anhydrase 4 impairs pH regulation and causes retinal photoreceptor degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:255–265. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ballermann BJ. Glomerular endothelial cell differentiation. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1668–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]