Significance

Voltage-sensing phosphatase (VSP) dephosphorylates phosphoinositides in a voltage-dependent manner. The molecular mechanisms by which the voltage-sensor domain of VSP activates the catalytic activity of the cytoplasmic region still remain unknown. Using a method of incorporation of a fluorescent unnatural amino acid, 3-(6-acetylnaphthalen-2-ylamino)-2-aminopropanoic acid (Anap), in the catalytic region, we revealed that some loops in the catalytic region move on membrane depolarization and that the catalytic region is located beneath the plasma membrane irrespective of the membrane potential. Furthermore, fluorescence change of Anap in the C2 domain showed multiple voltage-dependent activated states and protein conformation, which is sensitive to substrate availability in the active center. These findings provide novel insights into the mechanisms of voltage-dependent catalytic activity of VSP.

Keywords: VSP, unnatural amino acid, phosphatase

Abstract

The cytoplasmic region of voltage-sensing phosphatase (VSP) derives the voltage dependence of its catalytic activity from coupling to a voltage sensor homologous to that of voltage-gated ion channels. To assess the conformational changes in the cytoplasmic region upon activation of the voltage sensor, we genetically incorporated a fluorescent unnatural amino acid, 3-(6-acetylnaphthalen-2-ylamino)-2-aminopropanoic acid (Anap), into the catalytic region of Ciona intestinalis VSP (Ci-VSP). Measurements of Anap fluorescence under voltage clamp in Xenopus oocytes revealed that the catalytic region assumes distinct conformations dependent on the degree of voltage-sensor activation. FRET analysis showed that the catalytic region remains situated beneath the plasma membrane, irrespective of the voltage level. Moreover, Anap fluorescence from a membrane-facing loop in the C2 domain showed a pattern reflecting substrate turnover. These results indicate that the voltage sensor regulates Ci-VSP catalytic activity by causing conformational changes in the entire catalytic region, without changing their distance from the plasma membrane.

Voltage-sensor domains confer the voltage dependency to pore domains of voltage-gated ion channels and voltage-sensing phosphatase (VSP). In some proteins, the voltage-sensor domain also provides an ion permeation pathway (1–3). The VSP is a voltage-dependent phosphoinositide phosphatase (4–8), which is composed of two regions: a voltage-sensor domain homologous to that of voltage-gated ion channels and a cytoplasmic catalytic region (4). The catalytic region shows a high degree of similarity to the phosphatase tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), which is known as a tumor suppressor. PTEN and the catalytic region of VSP are both composed of a phosphatase domain, which contains the phosphatase active center, and a C2 domain, which is reportedly responsible for membrane binding (9–12). In addition, a linker region called the phosphoinositide binding motif (PBM) is situated between the voltage sensor and the catalytic region of VSP (13–16).

Molecular mechanisms of coupling between the voltage-sensor domain and the catalytic region in VSP still remain unclear. In the recently reported crystal structures of the catalytic region of VSP, the PBM interacts with a loop structure in the phosphatase domain (17, 18), named the “gating loop.” This structure suggests two distinct conformations (18) and raises the possibility that movement of the voltage sensor induces conformational changes in the gating loop by altering the conformation of the PBM. Our previous study using a mutant with a voltage sensor trapped into an intermediate state has suggested that enzymatic activity is graded, dependent on the state of the voltage-sensor domain (19). A recent study with rapid detection of change of catalytic products (PI(3,4)P2, PI(4,5)P2, and PI4P) as readout of phosphatase activity provided evidence that distinct states of the voltage sensor are coupled to multiple states of the catalytic region probably with distinct preference for phosphoinositide species (PIP3 versus PIP2s) (20). However, little information is available for the motion of the catalytic region of VSP driven by the operation of the voltage-sensor domain. To address these issues, we used a method of genetic incorporation of an environment-sensitive fluorescent amino acid analog, 3-(6-acetylnaphthalen-2-ylamino)-2-aminopropanoic acid (Anap), for site-specific labeling of the catalytic region of Ciona intestinalis VSP (Ci-VSP) (21–24). Because Anap is comparable in size to other amino acids, its incorporation causes a minimal perturbation of the protein’s structure. Results show that the voltage sensor regulates Ci-VSP catalytic activity by inducing conformational changes in both the phosphatase and C2 domains, not accompanied by a significant change of a distance from the plasma membrane. We also report that fluorescence change of Anap is consistent with the presence of multiple voltage-dependent states and with protein conformation, which is sensitive to substrate availability in the active center.

Results

Voltage-Dependent Fluorescence Change of Anap Introduced into the Cytoplasmic Region of Ci-VSP.

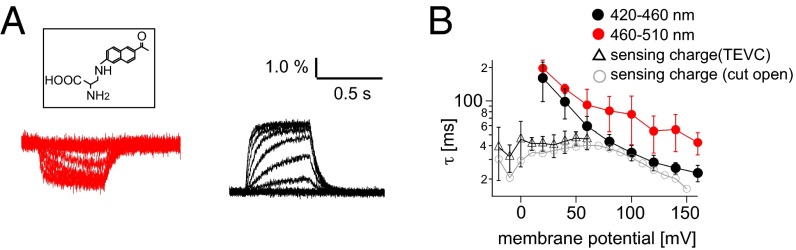

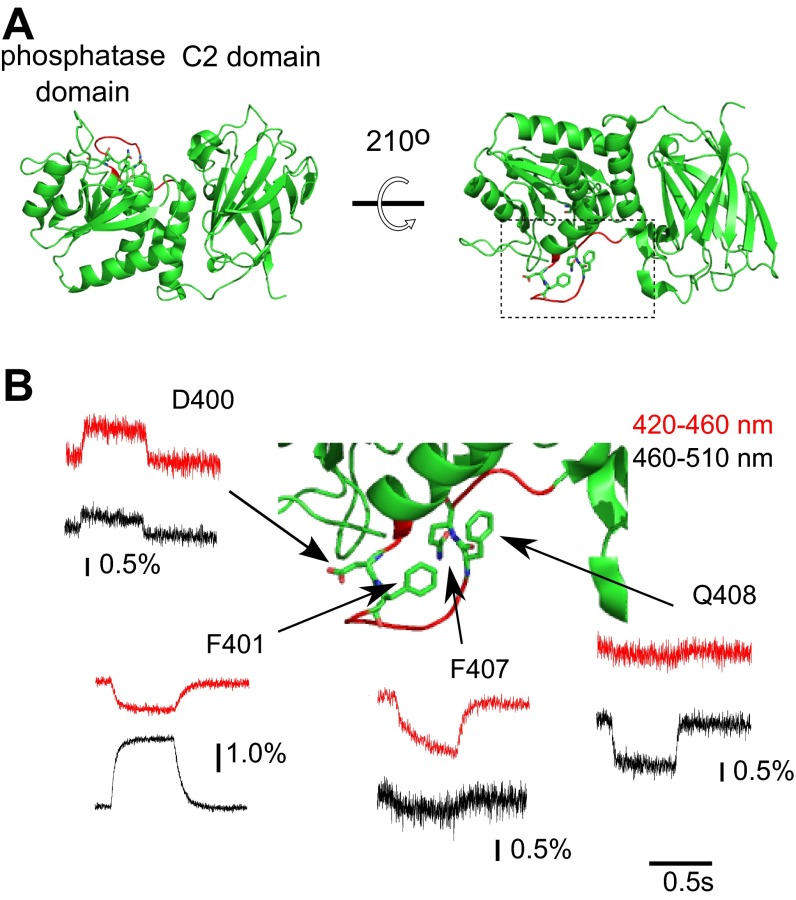

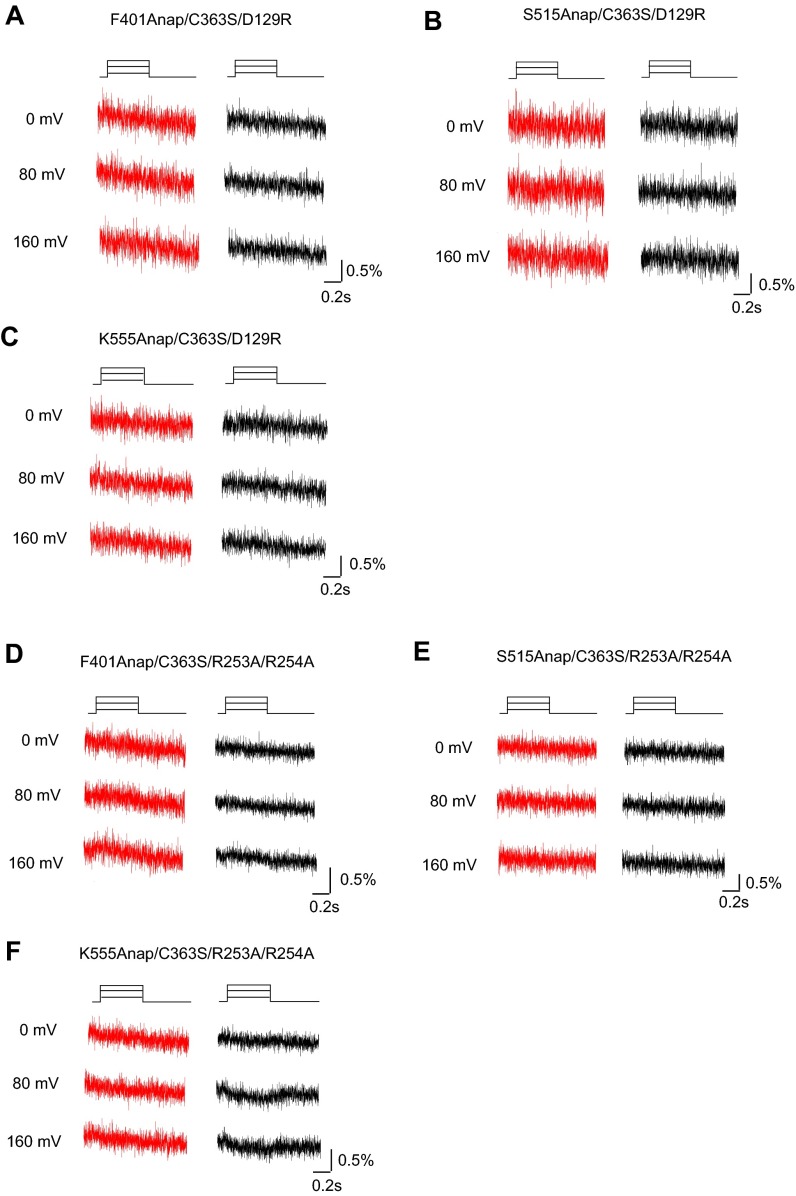

Earlier crystallographic studies of the catalytic region of Ci-VSP suggest operation of the gating loop in the phosphatase domain regulates the opening and closing of the active center, and this movement is controlled by the voltage sensor (18). To determine whether voltage-sensor movement induces gating loop motion, we incorporated Anap at four sites within the gating loop (D400, F401, F407, and Q408) of Ci-VSP containing an enzyme-inactive mutation (C363S) and expressed the protein in Xenopus oocytes. We used two band-pass emission filters, 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm, to detect Anap fluorescence (Fig. S1). We found that the fluorescence intensity changed in a voltage-dependent manner in all four sites (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). Kinetics of the fluorescence change of Anap-incorporated F401 were faster than that of the charge movement of the voltage sensor of WT Ci-VSP in lower voltages than 50 mV but exhibit similar kinetics to those of the charge movement at higher voltages (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, no fluorescence changes were detected when another mutation (D129R) was introduced that immobilized the voltage sensor (25) (Fig. S3). Furthermore, we introduced a mutation into the PBM motif (R253A/R254A) that reportedly causes an uncoupling between the voltage-sensor movement and the catalytic activity (13, 14). No voltage-dependent fluorescence changes were detected when Anap was incorporated at F401 with the R253A/R254A mutations of the PBM motif (Fig. S3).

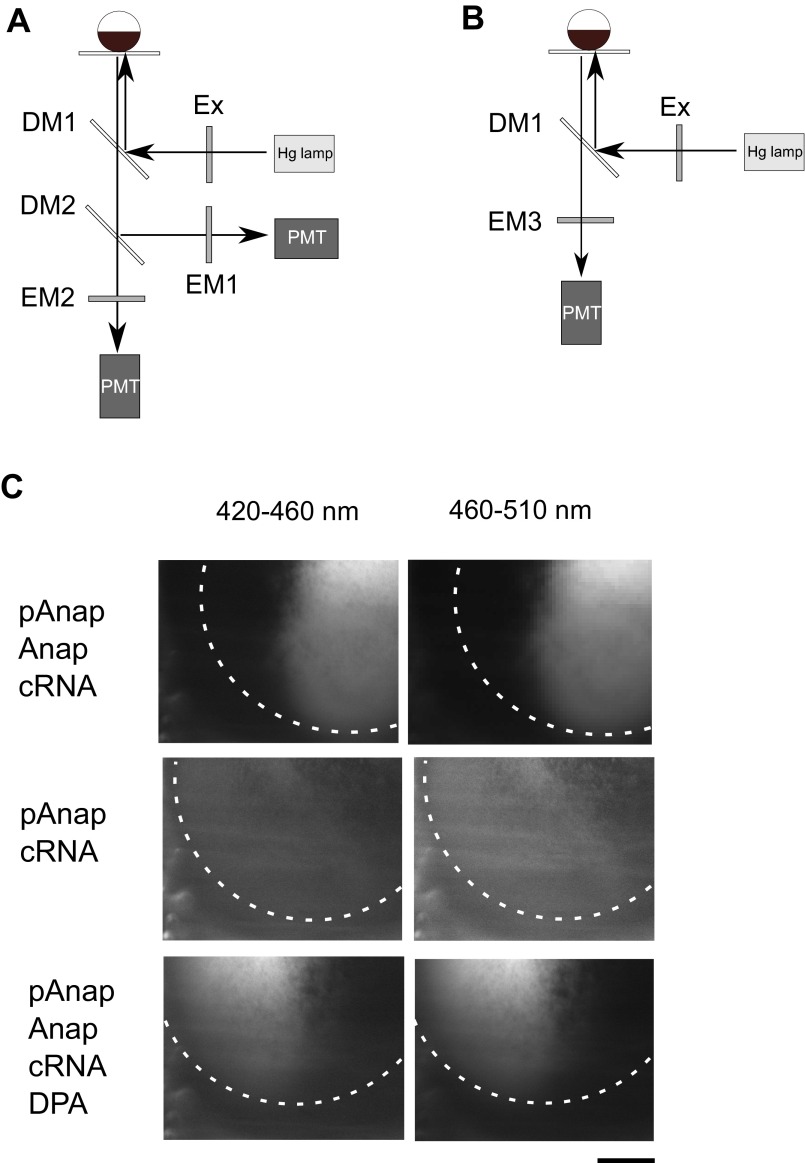

Fig. S1.

Optical setups used to measure Anap fluorescence and images of oocytes. (A) Optical setup used for all but the FRET experiments. (B) Optical setup used for FRET experiments. Ex (excitation filter): 330–385 nm (Olympus), DM (dichroic mirror) 1: 400 nm (Olympus), DM2: 458 nm (Olympus), EM (emission filter) 1: 420–460 nm (Olympus), EM2: 460–510 nm (Olympus), EM3: 420–520 nm (Semrock). PMT, photomultiplier tube. (C) Images of oocytes. (Left and Right) Images observed using the 420–460 nm and the 460–510 nm, respectively. (Top) Oocyte injected with pAnap, Anap, cRNA encoding Anap-incorporating Ci-VSP. (Middle) Oocyte injected with pAnap and cRNA but not Anap. (Bottom) Oocyte injected with pAnap, Anap, and cRNA encoding Anap-incorporating Ci-VSP followed by staining with DPA. (Scale bar, 500 μm.)

Fig. 1.

Voltage-dependent changes of Anap fluorescence. (A) Representative changes in fluorescence from Anap incorporated at F401. Red and black are the fluorescences detected using 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm band-pass emission filters, respectively. Voltage steps were applied from −60 mV to 160 mV in 20-mV increments. (Inset) Structure of Anap. (B) Time constant of the fluorescence change of Anap incorporated into F401 and the charge movement of WT Ci-VSP. The moved charges were estimated by the integration of on-sensing currents. The fluorescence elicited by the step pulses and the integrated currents were fit by the single exponential equation. The data of sensing charge measured from the cut-open oocyte was derived from a previous paper (the same dataset used for figure 1 C and D of ref. 4) (gray circle). Data are shown as the mean ± SD [n = 5, 5, and 5 for the 420–460 nm, the 460–510 nm filter, and on-sensing charge with TEVC (triangle), respectively].

Fig. S2.

Voltage-dependent change of Anap fluorescence in the gating loop. (A) Overview of the structure of the Ci-VSP catalytic region (PDB ID, 3V0H). The gating loop is shown in red. (B) Enlarged view of the region enclosed by the dotted lines in A. Traces show the voltage-dependent changes in the fluorescence of Anap incorporated into the gating loop elicited by the test pulses to 160 mV. Red and black traces indicate the fluorescence changes detected using 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm emission filters, respectively.

Fig. S3.

Anap fluorescence from voltage-sensor immobile mutant and PBM mutant. (A–C) Anap fluorescence did not change in the Ci-VSP voltage-sensor immobile mutants. Shown is fluorescence from D129R/C363S/F401Anap (A), D129R/C363S/S515Anap (B), and D129R/C363S/K555Anap (C). Red and black traces indicate the fluorescence measured using the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm emission filter, respectively. (D–F) Changes of Anap fluorescence were severely diminished in the PBM mutant that is known to be critical for coupling between voltage sensor and phosphatase in Ci-VSPs (13, 14). Shown is the fluorescence from R253A/R254A/C363S/F401Anap (D), R253A/R254A/C363S/S515Anap (E), and R253A/R254A/C363S/K555Anap (F). The color code is the same and in A–C.

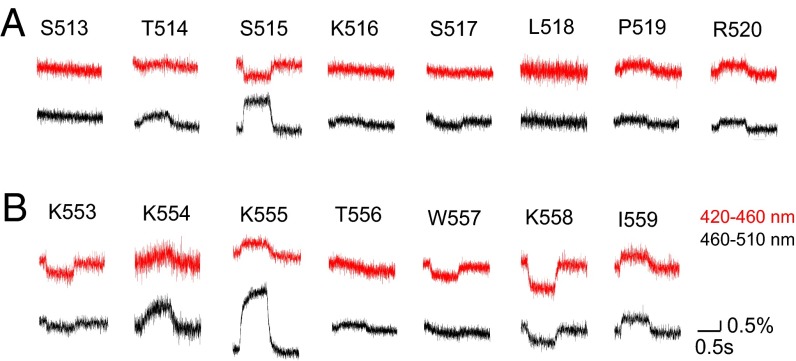

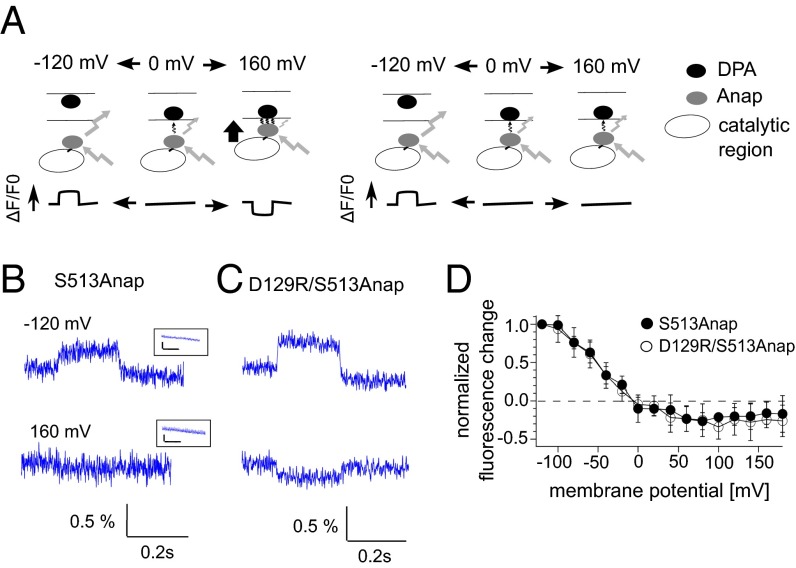

We also examined whether the C2 domain, which is not directly connected to the voltage-sensor domain, moves upon voltage-sensor activation. Anap was incorporated into the 515 loop (from S513 to R520) and Cα2 loop in the C2 domain (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4). Voltage-dependent fluorescence changes were observed at six of the eight labeled sites within the 515 loop, but not at S513 or L518 (Fig. 2A), whereas fluorescence changes were observed at all of the labeled sites in the Cα2 loop (Fig. 2B). When Anap was incorporated in the background of a voltage-sensor immobile mutation (D129R) or PBM mutation, the voltage-dependent changes in fluorescent signal from both S515Anap and K555Anap, which otherwise showed the largest fluorescence change in the 515 and Cα2 loops, respectively, were lost (Fig. S3). We found the fluorescence changed in both same and opposite directions between the 420–460 nm and the 460–510 nm filters. The direction of fluorescence change may include the information of how the conformation changed. However, we analyzed the only magnitude of the fluorescence without paying much attention to the direction of change in this study because detailed mechanisms of change of Anap fluorescence are not known so far.

Fig. 2.

Voltage-dependent changes in fluorescence from Anap incorporated into the 515 and Cα2 loops in the C2 domain.Changes in the fluorescence of Anap in the 515 loop (A) and the Cα2 loop (B) evoked by 160-mV test pulses, respectively.

Fig. S4.

Voltage-dependent changes of fluorescence from Anap incorporated into the 515 and Cα2 loops of the C2 domain. (A) Amino acid alignment of the C2 domains of Ci-VSP and PTEN. The 515 loop and the Cα2 loop are indicated by the black bars. (B) Overview of the Ci-VSP catalytic region (PDB ID, 3V0H). The 515 loop is shown in red. (C) Enlarged view of the structure enclosed by dotted lines in B. Traces show changes in the fluorescence of Anap in the 515 loop evoked by 160-mV test pulses. (D) Overview of the catalytic region (PDB ID, 3V0H). The Cα2 loop is shown in red. (E) Enlarged view of the structure enclosed by dotted lines in D. Traces show changes in the fluorescence of Anap in the Cα2 loop evoked by 160-mV test pulses.

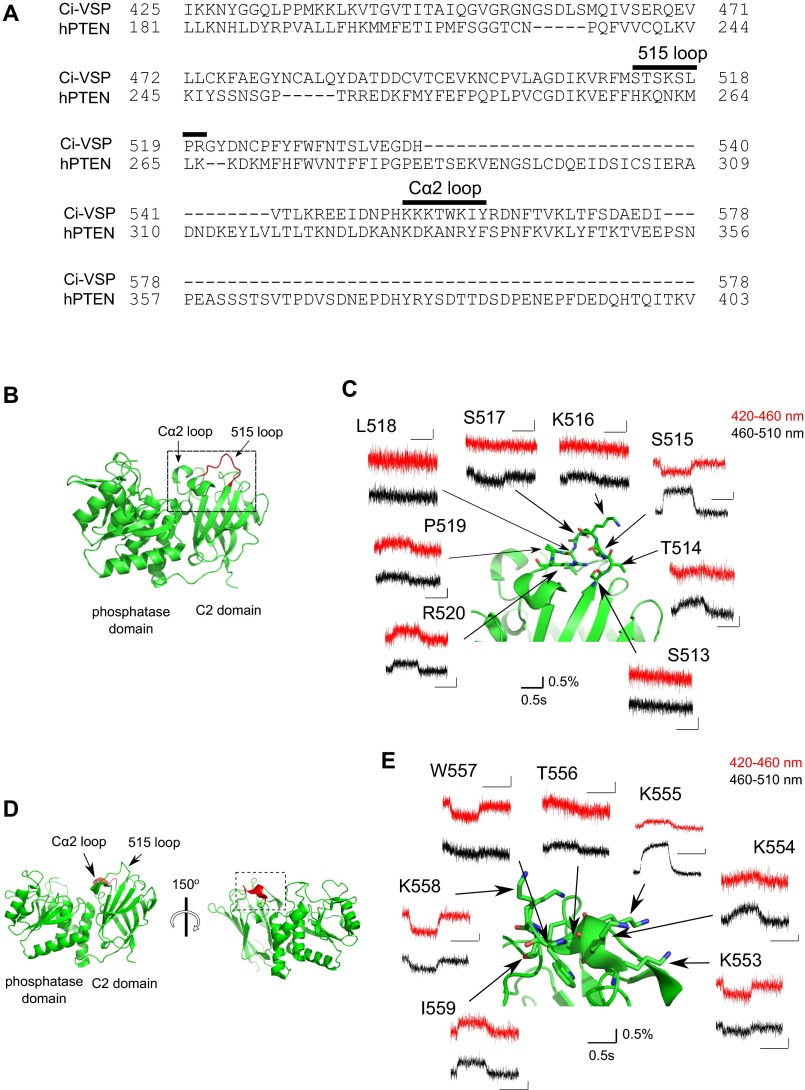

We next determined how fast the phosphatase and C2 domains move upon membrane depolarization (Fig. 3 and Fig. S5). The rising phases of the normalized fluorescence changes at F401Anap, S515Anap, and K555Anap, which showed the largest fluorescence changes in each loop, were fitted by single exponential equation. Estimated delays in the fluorescences through both the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm emission filters upon the depolarizing step to 160 mV were from 2 ms to 4 ms, on average, in all three constructs, and did not differ significantly (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Estimation of the delay to onset of the fluorescence changes elicited by depolarization. (A) Magnified views of the changes in fluorescence from F401Anap/C363S. (Left and Right) Fluorescence changes detected using 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm emission filters, respectively. (Insets) Overviews of the fluorescence data. Black lines above the fluorescence data are actual membrane potentials, and the median time of the voltage change from −60 mV to 160 mV was defined as the time of depolarization, which is indicated by an arrow. The fluorescence changes were fitted by the single exponential equation (the blue curve). The dotted line indicates the initial level, which was defined as the average of the fluorescence intensity from 0 ms to 30 ms after the beginning of the protocol, during which the voltage was clamped at −60 mV. The intersection of the exponential curve (blue) and the dotted line was defined as the onset of the fluorescence change. Trace was shown from the middle of the first 30 ms. (B) Quantitative comparison of the delay to onset of the fluorescence change after depolarization. Red and black bars indicate the delay estimated from the data obtained using 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm filters, respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 4, 4, and 6 for F401Anap/C363S, S515Anap/C363S, and K555Anap/C363S, respectively).

Fig. S5.

Estimation of the delay to onset of the fluorescence changes elicited by depolarization. (A and B) Magnified views of the changes of fluorescence from S515Anap/C363S (A) and K555Anap/C363S (B) Ci-VSP mutants. (Left and Right) Fluorescence changes detected using the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm emission filters, respectively. (Insets) Overviews of the fluorescence data. See the legend of Fig. 3 for the meaning of black and dotted lines, the blue curve, and arrows.

FRET Between Anap and Dipicrylamine Embedded in the Plasma Membrane Does Not Detect a Large Change in Distance Between the Catalytic Region of Ci-VSP and the Membrane.

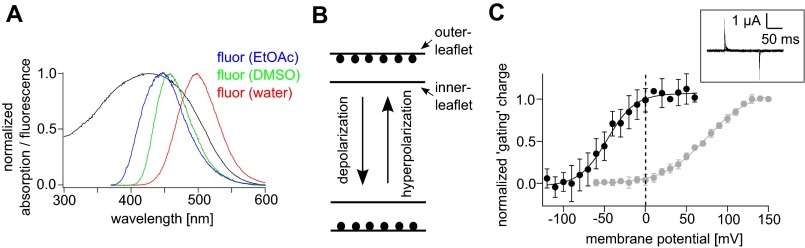

The results so far show that voltage-sensor movement regulates the conformation of the catalytic region. However, because Ci-VSP substrates are membrane phosphoinositides, it is also possible that the voltage sensor regulates phosphatase activity, changing the distance between the catalytic region and the plasma membrane, thereby modulating the availability of substrate close to the active site of the enzyme. To test this possibility, we measured FRET between the Ci-VSP catalytic region and the plasma membrane. The catalytic region was labeled with Anap at S513, as the site where Anap fluorescence was unchanged by membrane depolarization (Fig. 2A), and the plasma membrane was stained with dipicrylamine (DPA) as FRET acceptor (Figs. S1C and S6A) (26–28). We measured Anap fluorescence to evaluate the FRET efficiency because DPA is not a fluorescent molecule. It is known that DPA translocates between the outer and inner leaflets of the plasma membrane in a voltage-dependent manner (26, 27) (Fig. S6 B and C). To detect voltage-dependent movement of the catalytic region using FRET, membrane potential was held at 0 mV, a level at which the voltage sensor of Ci-VSP is in a nearly resting state and the majority of DPA is on the inner leaflet (Fig. 4A). When the membrane potential is hyperpolarized from 0 mV to −120 mV, the intensity of the Anap fluorescence should increase because of the decrease in FRET efficiency due to the transition of DPA toward the outer leaflet. When the membrane is depolarized from 0 mV to 160 mV, the Anap fluorescence should decrease due to the increase in FRET efficiency as the catalytic region is pulled toward the plasma membrane (Fig. 4A, Left). On the other hand, Anap fluorescence should not be changed if the catalytic region does not move toward the membrane, even when the membrane is depolarized to 160 mV (Fig. 4A, Right). We measured Anap fluorescence in a wider bandwidth for emission (the 420–520 nm emission filter) to increase the fluorescence intensity detected by the photomultiplier tube (PMT) (Fig. S1A). An increase in Anap fluorescence was observed in the presence of DPA when the membrane was hyperpolarized to −120 mV in oocytes expressing Ci-VSP (S513Anap/C363S) (Fig. 4B, Upper). Next, we changed the membrane potential from 0 mV to 160 mV and found that the fluorescence slightly decreased (Fig. 4B, Lower).

Fig. S6.

FRET between DPA and Anap. (A) DPA absorption spectrum (black) and Anap fluorescence spectra. (B) Diagram illustrating DPA displacement between the inner and outer membrane leaflets in response to the voltage changes. (C) Voltage dependence of DPA movement in Xenopus oocyte. (Inset) Transient current derived from translocation of DPA in membrane of oocyte, which was incubated with 20 μM DPA in a bath solution. Voltage steps were evoked from −120 mV to 60 mV in 10-mV increments. The holding potential was −100 mV. Black circles indicate the charges integrated from the off-current based on DPA translocation plotted against the membrane potential. Gray circles indicate the normalized gating or sensing charge of WT Ci-VSP. Data are shown in the mean ± SD (n = 7 and 5 for DPA and Ci-VSP, respectively).

Fig. 4.

FRET between Anap and DPA embedded in the plasma membrane. (A) Strategy for examining the voltage-dependent movement of the catalytic region toward the plasma membrane. Text provides details. (B and C) Changes in the fluorescence of Anap incorporated at S513 within active (B) and immobilized (C) forms of the voltage sensor in the presence of DPA. (Upper and Lower) Anap fluorescence evoked by the test pulses to −120 mV and +160 mV, respectively. (Insets) Anap fluorescence in the absence of DPA at −120 mV. Vertical and horizontal bars in the Insets indicate 0.25% and 0.2 s, respectively. (D) Voltage dependency of Anap fluorescence in the presence of DPA. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 7 for both S513Anap/C363S and D129R/S513Anap/C363S).

To examine whether this decrease resulted from movement of the catalytic region, we also tested a Ci-VSP mutant (D129R/S513Anap/C363S) in which the voltage sensor was immobilized (29). We found that the decrease in fluorescence persisted in the voltage-sensor immobile form (Fig. 4C). Plots of the normalized fluorescence changes in S513Anap/C363S and D129R/S513Anap/C363S against the membrane voltage showed no significant difference (Fig. 4D). The voltage dependencies of the FRET efficiency (Fig. 4D) were more like that of DPA movement than the charge–voltage (Q–V) relationship of Ci-VSP (Fig. S6C), suggesting no voltage-dependent change in the distance between the catalytic region and the plasma membrane. The Q–V relationship for DPA was not completely saturated around 0 mV (Fig. S6C), consistent with an earlier study (27). This finding indicates that DPA is not situated entirely within the inner leaflet at 0 mV, but translocates to the inner leaflet at 160 mV, which would explain why we observed a decrease of the fluorescence at 160 mV in the voltage-sensor immobile mutant. Thus, FRET experiments revealed no voltage-dependent change in the distance between the catalytic region and the plasma membrane.

Distinct Fluorescence–Voltage Relationships Between the Enzyme-Active and -Inactive Forms of Ci-VSP.

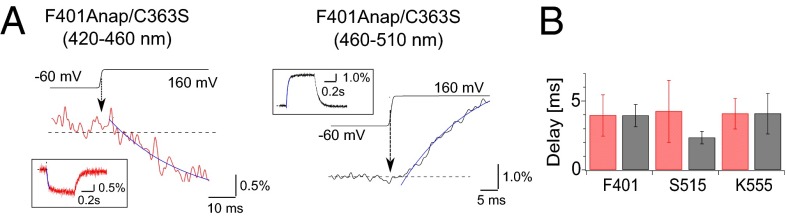

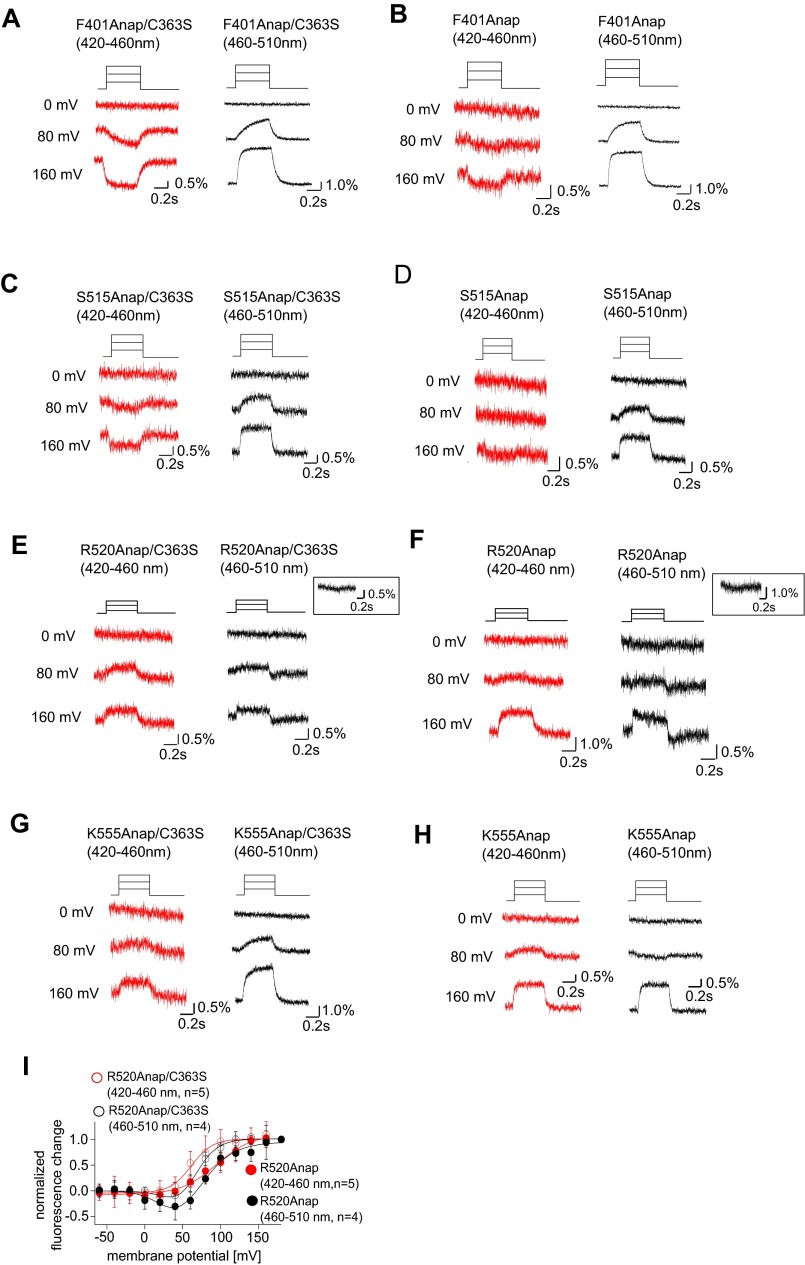

We next compared changes in Anap fluorescence in enzymatically active and inactive forms (C363S) of Ci-VSP and systematically analyzed their voltage dependency. One site in the gating loop of the phosphatase domain (F401) and three sites in the C2 domain (S515, R520, and K555) were analyzed. The kinetics of the fluorescence changes at F401Anap did not differ significantly between the active and inactive forms of the enzyme (Fig. 5A and Fig. S7). The fluorescence–voltage (F–V) relationship for fluorescence measured using the 420–460 nm filter was identical to that measured using the 460–510 nm filter both in the active and inactive forms (Fig. 5B). With the active form, the F–V relationships for the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm signals were shifted toward higher voltages compared with the inactive form (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

F–V relationship of the enzyme-active and -inactive forms of Ci-VSP. (A, C, and E) Representative fluorescence changes of Anap incorporated into F401 (A), S515 (C), and K555 (E) in the enzyme-active or -inactive forms. (B, D, and F) F–V relationship for F401Anap (B), S515Anap (D), and K555Anap (F). Red and black are the fluorescences detected using 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm band-pass emission filters, respectively. Open and filled circles indicate data from the inactive and active enzymes, respectively.

Fig. S7.

Voltage-dependent fluorescence change of Anap in the enzyme-active and -inactive forms of Ci-VSP. (A–H) Representative fluorescence changes of Anap incorporated into F401 (A and B), S515 (C and D), R520 (E and F), and K555 (G and H) in both the enzyme-active and -inactive forms (C363S) of Ci-VSP. The color code is the same as in Fig. S2. (Top) Pulse protocol. (Insets in E and F) Fluorescence changes at 40 mV. (I) F–V relationship of R520Anap in both the enzyme-active and -inactive forms.

The F–V relationship at S515Anap (in the 515 loop of the C2 domain) showed a slight rightward shift in the 460–510 nm fluorescence from the active enzyme compared with the inactive form (Fig. 5 C and D). For the active enzyme, the 420–460 nm signal was too small to analyze its voltage dependence (Fig. S7). The F–V relationship for R520Anap, which is also located in the 515 loop, had two components (Fig. S7I). The fluorescence in the bandwidth of 460–510 nm from both the inactive and active forms of the enzyme decreased at around 50 mV and then increased at higher membrane voltages.

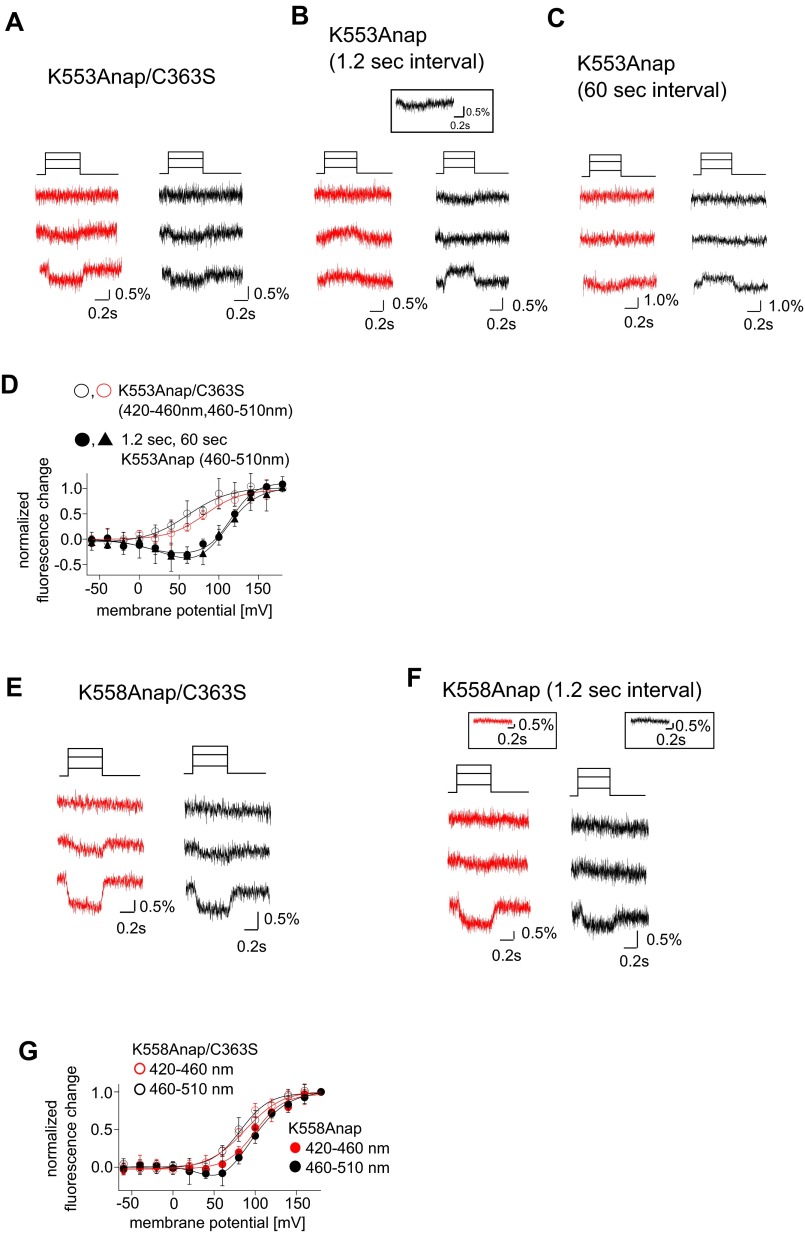

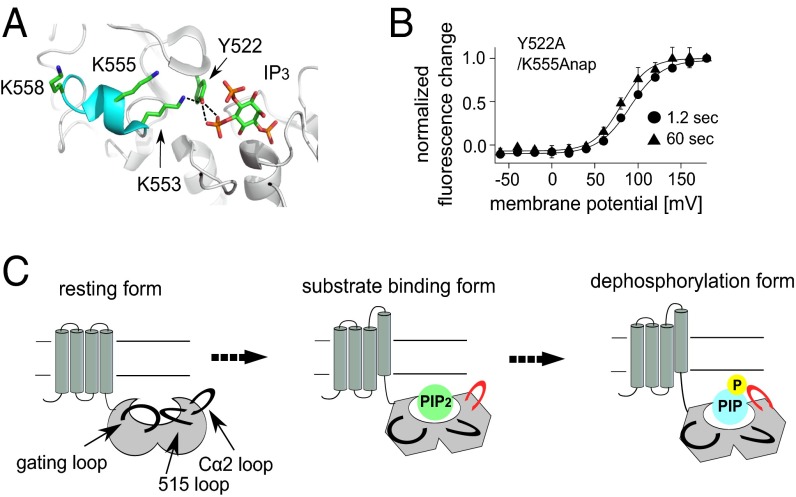

The F–V relationship for the 460–510 nm signal from K555Anap (Cα2 loop of the C2 domain) had one component in the inactive enzyme, but two components in the active form (Fig. 5 E and F). The F–V relationship for the active enzyme was shifted slightly toward higher voltages compared with the inactive form (Fig. 5F), as was the case with the 420–460 nm signals from F401Anap and S515Anap. The F–V relationships of K553Anap and K558Anap, other sites in Cα2 loop, were also examined (Fig. S8). Both K553Anap and K558Anap exhibited two components of fluorescence change in the active enzyme, but only one in the inactive mutant as in the case of K555Anap (Fig. S8). We verified that Ci-VSP mutants into which Anap was incorporated in the above sites all retained the voltage-dependent catalytic activity using the Kir3.2 channel (Fig. S9).

Fig. S8.

Changes in the fluorescence from K553Anap and K558Anap. (A and B) Representative changes of fluorescence from K553Anap incorporated into the inactive (A) and active (B) forms of Ci-VSP. Fluorescence was measured using a 1.2-s test pulse interval. The color code is the same as in Fig. S2. (Top) Pulse protocol. (Inset in B) Representative fluorescence change at 40 mV. (C) Changes in the fluorescence measured using a 60-s test pulse interval with the active form of the enzyme. The color code and voltages for each dataset are the same as in A and B. In A–C, the second, third, and fourth panels from the top depict the fluorescence changes at 0 mV, 80 mV, and 160 mV, respectively. (D) F–V relationship for K553Anap. Open and filled circles, respectively, depict K553Anap fluorescence in the inactive and active forms of Ci-VSP measured using 1.2-s test pulse intervals. Triangles depict the normalized fluorescence in the active enzyme measured using 60-s test pulse intervals. Red and black indicate the fluorescence data detected using the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm emission filters, respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 4 and 4 for 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm fluorescence from the inactive enzyme; n = 4 and 3 for the fluorescence measured using 1.2-s and 60-s test pulse intervals with the active enzyme). (E and F) Representative changes of fluorescence from K558Anap incorporated into the inactive (E) and active (F) forms of Ci-VSP. Fluorescence was measured using a 1.2-s test pulse interval. The second, third, and fourth panels from the Top depict the fluorescence changes at 0 mV, 80 mV, and 160 mV, respectively. (Inset in F) Representative fluorescence change at 60 mV. (G) F–V relationship for K558Anap. Open and filled circles, respectively, depict the inactive and active forms of the enzyme. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 5 and 5 for data from the inactive form of the enzyme collected through the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm filters, respectively; n = 8 and 8 for data from the active form of the enzyme collected through the 420–460 nm and 460–510 nm filters, respectively).

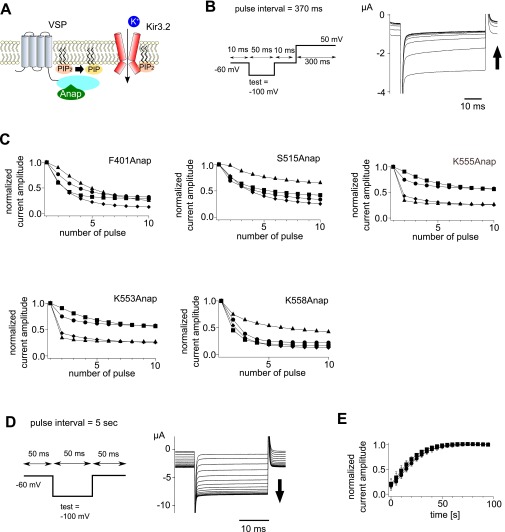

Fig. S9.

Measurements of the catalytic activity of Ci-VSP incorporating Anap. (A) Scheme used to measure the catalytic activity of Ci-VSP. The decrease in the Kir current associated with the PI(4,5)P2 level in the membrane. (B, Left) Pulse protocol. (Right) Superimposition of Kir currents elicited by repeated test pulses in oocytes expressing Ci-VSP (F401Anap). Current amplitude declined as the protocol was repeated (arrow). (C) Time course of decrease in Kir currents in oocytes expressing Ci-VSP with Anap incorporated at the respective sites of F401, S515, K555, K553, and K558. Different symbols depict data from different oocytes. (D) Recovery of the Kir current. (Left) Pulse protocol. (Right) Superimposition of Kir currents elicited through repetition of the protocol (Left) every 5 s. The current was measured after phosphoinositide depletion. The holding potential was −60 mV, at which Ci-VSP is in a resting state. (E) Time course of recovery of Kir current after depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by voltage-evoked enzyme activities of Anap-incorporating Ci-VSP. Circles, squares, and triangles depict results of F401Anap, S515Anap, and K555Anap, respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 5, 4, and 5 for F401Anap, S515Anap, and K555Anap, respectively).

The Voltage-Dependent Movement of the Cα2 Loop Is Sensitive to Substrate Availability.

Our analyses revealed that the F–V relationships were shifted between the enzyme-active and -inactive forms in all sites we examined, including F401, S515, and K555. The F–V relationship for F401Anap, S515Anap showed only one component in both the enzyme-inactive and -active forms, whereas the F–V relationship for the 460–510 nm fluorescence from K555Anap in the Cα2 loop showed one and two components in the enzyme-inactive and -active forms of Ci-VSP, respectively (Fig. 5F). In the pulse protocol with a 1.2-s pulse interval, phosphoinositide substrates were depleted after activation of phosphatase of the Anap-incorporated enzyme-active form of Ci-VSP and there was little available substrate in the plasma membrane due to the incomplete recovery of phosphoinositides (Fig. S9 D and E) mediated by endogenous kinases (30, 31). Therefore, one possible explanation for the difference in the F–V relationships between the active and inactive forms is that the observed fluorescence was affected by the level of substrates in the plasma membrane.

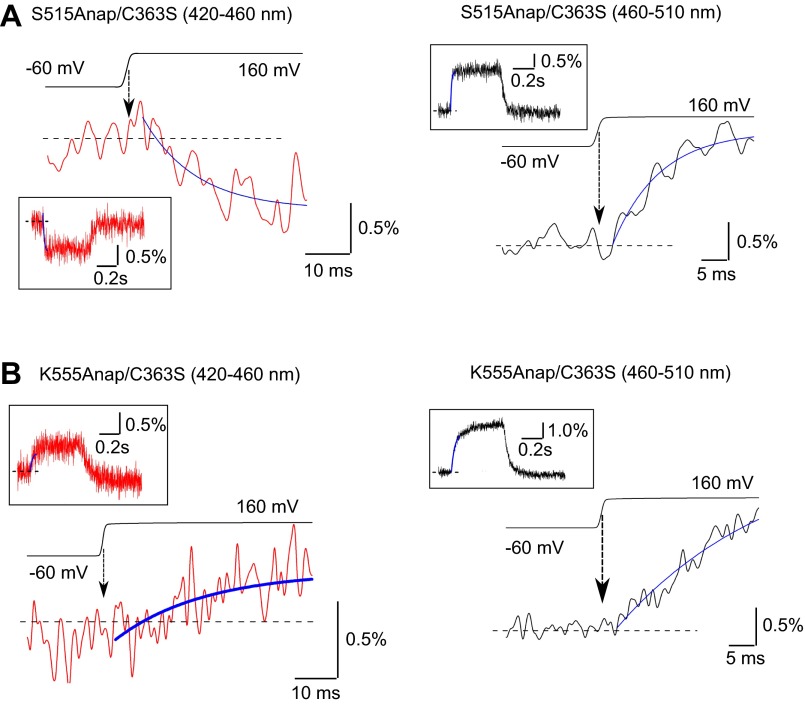

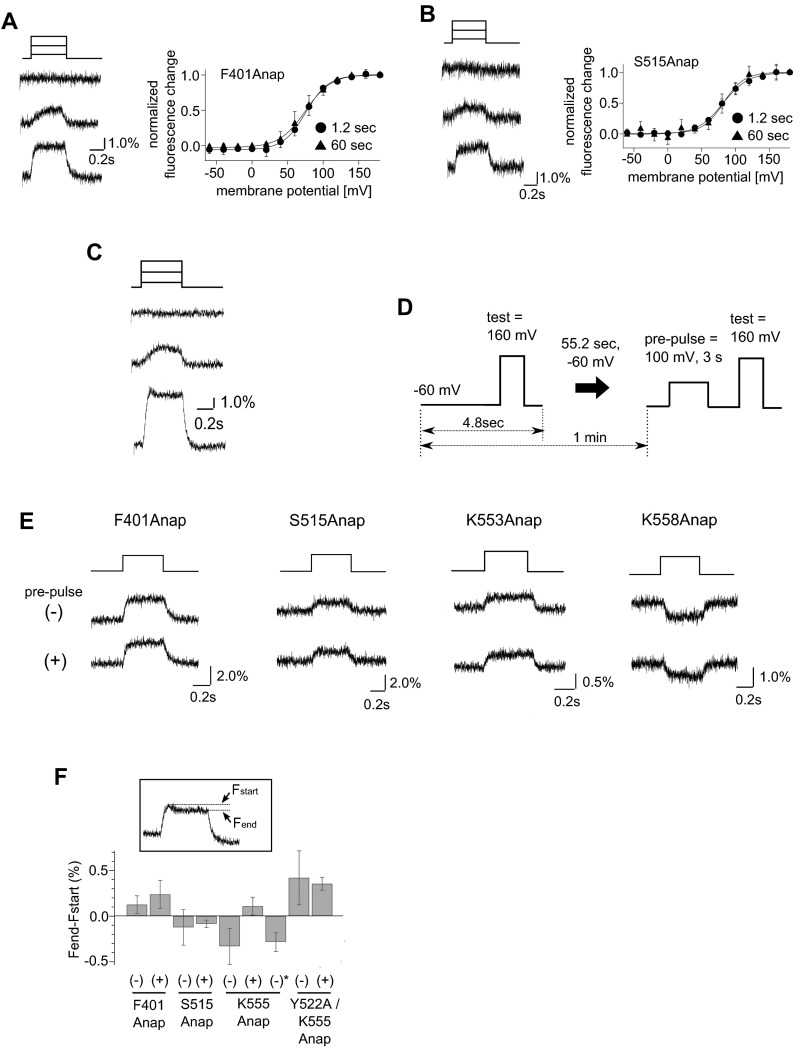

To determine how the level of available substrate affects Anap fluorescence, we measured the signal using longer pulse intervals (60 s). We reasoned that with this pulse protocol with a long interval the level of phosphoinositides recovers until the next episode of the test pulse, because the Kir current could be restored within around 50 s to its original amplitude by clamping the membrane voltage at −60 mV, a voltage at which Ci-VSP is silent (Fig. S9 D and E). The F–V relationships for both F401Anap and S515Anap appeared to be unaffected by the different pulse intervals (Fig. S10 A and B). By contrast, the F–V relationship for K555Anap showed one component when fluorescence was measured with a 60-s pulse interval, but two components when fluorescence was measured with a 1.2-s interval (Fig. 6A). In addition to the change in the F–V relationship, we found that the kinetics of the fluorescence change also differed between the 1.2-s and 60-s intervals in active Ci-VSP. The fluorescence from K555Anap measured at 60-s intervals showed a transient decrease just after the large increase evoked by the depolarizing test pulse to 160 mV (Fig. S10C, Bottom). This transient decrease was not observed when the fluorescence was measured at 1.2-s intervals (Fig. 5E).

Fig. S10.

Effect of the substrate availability on the fluorescence change of Anap. (A and B) Voltage dependence of the changes of fluorescence from F401Anap (A) and S515Anap (B) in the active form Ci-VSP. (Top) Pulse protocol. The fluorescence change at 0 mV (second from the Top), 80 mV (third from the Top), and 160 mV (Bottom) were recorded from the same oocyte. (Right) F–V relationships measured using 1.2-s test pulse intervals (circles) or 60-s test pulse intervals (triangles). (C) Voltage dependence of the changes of fluorescence from K555Anap in the enzyme-active form of Ci-VSP measured using 60-s test pulse interval. (Top) Pulse protocol, and the fluorescence change at 0 mV (second from the Top), 80 mV (third from the Top), and 160 mV (Bottom). (D) Pulse protocol used to assess the changes in the kinetics of Anap fluorescence elicited by changes of the availability of substrates in the plasma membrane. Depolarizing prepulse is for depleting phosphoinositides by activating phosphatase activities of Anap-incorporating Ci-VSP. (E) Effect of depletion of phosphoinositides by depolarizing prepulses on fluorescence for F401Anap, S515Anap, K553Anap, and K558Anap. (Top) Timing of the depolarization. (Middle and Bottom) Fluorescence changes at 160 mV in the absence and presence of a prepulse, respectively. (F) Quantitative comparison of the kinetics indicated by the arrow in the second panel from the Top in Fig. 6B. (Inset) Definition of Fstart and Fend, which were estimated as 50-ms averages of the normalized fluorescence at 70 ms and 420 ms after the onset of the test pulse, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Effect of phosphoinositide availability on the motion of the cytoplasmic region of Ci-VSP probed by Anap at K555. (A) F–V relationships measured using 1.2-s test pulse intervals (circles) or 60-s test pulse intervals (triangles). Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 4 and 9 for the fluorescence measured using 1.2-s and 60-s test pulse intervals, respectively). (B) Changes in the kinetics with altered phosphoinositides level induced by Ci-VSP activities in the same oocyte (Left, K555Anap; Right, Y522A/K555Anap). (Top) Timing of the depolarization. Arrows indicate decay in fluorescence that depends on a depolarizing prepulse. (Left Bottom) Fluorescence change in the absence of the prepulse, recorded 1 min after the measurement in the presence of the prepulse, which is shown in the second panel from the Bottom. Data are taken from the same oocytes.

To confirm whether the transient decrease in fluorescence was dependent on the level of substrate in the plasma membrane, we measured the fluorescence change in the absence and presence of a depolarizing prepulse in the same oocytes (Fig. 6B and Fig. S10D). We found the fluorescence decrease was not seen in the protocol with a prepulse (Fig. 6B) but was seen in the absence of a prepulse. Moreover, the hump could be restored by clamping the membrane voltage for 1 min at −60 mV, a voltage at which Ci-VSP is in a resting state (Fig. 6B). The prepulse-dependent change in fluorescence kinetics was not observed at F401Anap or S515Anap (Fig. S10E). These results show that substrate availability did not affect the F–V relationship or the kinetics of the fluorescence change at F401Anap or S515Anap, but did affect fluorescence from K555Anap, which suggests that movement of only the Cα2 loop is affected by substrate availability.

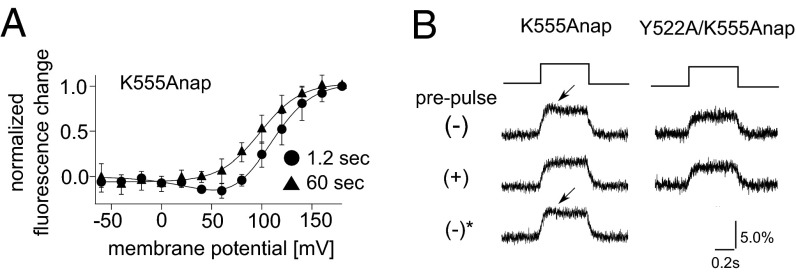

Crystal structures showed that the Cα2 loop is indirectly bound to the substrate by several hydrogen bonds mediated by Tyr522 (18) (Fig. 7A). To confirm that these hydrogen bonds are responsible for the Cα2 loop movement associated with the substrate metabolism, Tyr522 was mutated to alanine and the fluorescence change of Y522A/K555Anap was measured. The hump was not found by the depolarization test pulse to 160 mV in the absence of prepulse with a 60-s interval in the Y522A mutant (Fig. 6B), and the F–V relationship of Y522A/K555Anap measured with a 60-s interval did not have two components and was similar to that measured with a 1.2-s interval (Fig. 7B). Because the Y522A mutant was reported to retain the phosphatase activity to a level similar to that of WT protein but with the positive shift of voltage dependence (18), substrates should be depleted from the binding pocket on the 60-s membrane depolarization. These findings suggest that interactions between the Cα2 loop and the substrate via Tyr522 are involved in the substrate-dependent change of the fluorescence of K555Anap. The F–V relationships of three sites labeled in the Cα2 loop, K553, K555, and K558, were composed of one or two components dependent on the catalytic activity, whereas those in F401 (gating loop) and S515 (515 loop) were one component irrespective of the catalytic activity. These findings suggest that the catalytic activity of Ci-VSP is accompanied by movement of the Cα2 loop within the C2 domain.

Fig. 7.

Structure of the Cα2 loop and a model of the conformational change in the catalytic region of Ci-VSP. (A) Structure around the active center and Cα2 loop. The Cα2 loop is shown in cyan. IP3 is located at the active center (PDB ID code 3V0H) (18). (B) Voltage dependence of the changes in fluorescence from Y522A/K555Anap. Circles and triangles denote the normalized fluorescence measured using 1.2-s and 60-s test pulse intervals, respectively. Data are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 4 for both fluorescence detected using 1.2-s and 60-s test pulse intervals). (C) Proposed model of the conformation change in the catalytic region. Voltage-sensor activation induces conformational changes in the catalytic region such that the 515 and Cα2 loops as well as the gating loop all move, and the substrate is able to bind to the active center (“substrate binding form”). Once the substrate is bound, it is dephosphorylated (“dephosphorylation form”), which may be accompanied by a conformational change in the Cα2 loop (shown in red).

Discussion

To detect the voltage-dependent motion of the cytoplasmic catalytic region of Ci-VSP, we incorporated a fluorescent unnatural amino acid, Anap, into the protein using a genetic method with a Xenopus oocyte expression system. Our approach brought the following findings. First, three loops in the catalytic region move in a voltage-dependent manner (Figs. 1 and 2) with similar timing (Fig. 3). Second, changes in the voltage dependency of the fluorescence introduced into some sites revealed two components (Fig. 5F and Figs. S7I and S8 D and G), suggesting distinct conformational changes in the catalytic region depending on the degree of voltage-sensor activation. Third, the FRET experiment provided no evidence of a change in the distance between the catalytic region and plasma membrane upon voltage-sensor activation (Fig. 4). Fourth, Anap on a single site, K555, of the Cα2 loop showed fluorescence change sensitive to the availability of substrates in the enzyme active center (Fig. 6), reflecting conformational changes associated with catalysis and/or substrate turnover (Fig. 7C).

A Fluorescent Unnatural Amino Acid Suggests Distinct Voltage-Dependent States of the Catalytic Region of Ci-VSP.

An earlier X-ray crystallographic study suggested a model in which the operation of the gating loop is associated with voltage-sensor movement (18). We now provide direct evidence that upon the voltage-sensor activation, the gating loop moves (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2) along with the 515 and Cα2 loops in the C2 domain (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the fluorescence of K553Anap and K555Anap decreased when the membrane was depolarized to around 50 mV, whereas those increased at higher voltages, and the fluorescence of K558Anap increased at around 50 mV and decreased at higher voltages (Fig. 5F and Fig. S8 D and G). In addition, these two components of the F–V relationships were also observed in both the active and inactive forms of the enzyme with incorporated R520Anap (Fig. S7I). These observations indicate that the catalytic region does not have only two states corresponding to the resting and activated state of the voltage sensor but could have an intermediate state, which depends on the degree of activation of the voltage sensor. We have previously conducted an experiment of trapping the intermediate state of the voltage sensor (19) to show that the catalytic activity is graded. Experiments of monitoring the levels of phosphoinositides using GFP-fused pleckstrin homology domains suggests that the substrate specificity could be altered in a voltage-dependent manner (18, 32, 33). A recent study of several voltage-sensor mutants showing altered state transitions among three distinct states of voltage sensor combined with rapid detection of phosphoinositide change, as the readout of enzyme activity suggested that a distinct state of voltage sensor induces a distinct enzyme state with biased preference toward phosphoinositide species (PI(3,4,5)P3 versus PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2) (20). It will be interesting in the future to address whether bidirectional changes of Anap fluorescence dependent on membrane voltage in our study reflect multiple states of the catalytic region with distinct enzyme properties.

Little or No Change in Distance Between the Ci-VSP Catalytic Region and the Plasma Membrane upon the Voltage-Sensor Activation.

We analyzed FRET between the Ci-VSP catalytic region and the plasma membrane to determine whether the distance between them changes during enzyme activation (Fig. 4). Before testing for this effect, the membrane was hyperpolarized to −120 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. We noted an increase in Anap fluorescence at −120 mV, which was caused by the displacement of DPA from the inner to the outer leaflet of the membrane (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6). This finding means that when the voltage sensor is in a resting state, the catalytic region remains close enough to the membrane for FRET to occur, and that Anap and DPA can serve as a FRET pair. In addition, there was no significant difference in the voltage-dependent change in the fluorescence between the voltage-sensor active and immobile mutants (Fig. 4D), which implies that activation of the voltage sensor does not lead to a change in the distance between the catalytic region and the membrane. However, we do not completely exclude the possibility that the catalytic region moves toward the membrane upon voltage-sensor activation within the detection limit of the FRET system. We thus conclude that our FRET experiment showed that the catalytic region remains beneath the plasma membrane while the voltage sensor is in the resting state and that any possible change in the distance between the catalytic region and the membrane upon voltage-sensor activation is smaller than the detection limit of our system.

The Substrate Availability Is Associated with the Movement of the Cα2 Loop in the C2 Domain.

We found that, in three sites in the Cα2 loop, the F–V relationships of the active enzyme contained two components, whereas those of the inactive enzyme had only one component (Fig. 5F and Fig. S8 D and G). The influence of the substrate availability on K555Anap fluorescence was lost by the mutation of Y522, which mediates an indirect binding between the Cα2 loop and the substrate (18) (Figs. 6B and 7B). Furthermore, it has been reported that the neutralization of positive charges, K553, K554, K555, and K558 affected the substrate selectivity of the enzyme (32). These findings suggest that the concerted movement of the Cα2 loop is accompanied by the conformational change of the phosphatase domain for the catalytic activity of Ci-VSP. We also examined the effect of substrate availability on the fluorescence change of other sites of the Cα2 loop, K553Anap and K558Anap. The F–V relationships were distinct between the enzyme-active and -inactive forms, like K555Anap. However, the F–V relationships of both the enzyme-active and -inactive K553Anap had two components irrespective of whether the interval duration was 1.2 s or 60 s (Fig. S8D), and the depolarizing prepulse did not affect the kinetics of the fluorescence (Fig. S10E). The incorporation of Anap into K553 or K558 does not impair the catalytic activity as shown by measurements of the catalytic activities (Fig. S9C). One possible reason that only K555Anap among several sites in the Cα2 loop showed the substrate availability is that the side chain of Anap incorporated at K555 is located at a position exposed to an environment that is altered by the motion of the Cα2 loop, whereas the K553 and K558 side chains are not.

Based on a crystallographic study of the catalytic region of Ci-VSP, it was proposed that movement of the voltage sensor changes the gating loop conformation, which in turn opens a substrate-binding pocket near the active center, enabling substrate phosphoinositides to bind (18). We found that the fluorescent signal from Anap introduced into the gating loop changed in a voltage-dependent manner (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2), which supports the idea that voltage-sensor activation leads to movement of the gating loop. However, voltage-dependent movement was also seen in the 515 and Cα2 loops. The similar onsets of fluorescence changes in the three is consistent with the idea that the phosphatase and C2 domains move as a single unit (Fig. 3). We also found that movement of the Cα2 loop differed between the active and inactive enzymes (Fig. 5F and Fig. S8 D and G), and that a hump in the fluorescence change at K555Anap in the Cα2 loop was seen when phosphoinositides are not depleted (Fig. 6B). The kinetics of the change in K555Anap fluorescence when phosphoinositides are not depleted exhibited two phases: In the earlier phase, the fluorescence increased just after the onset of depolarization, whereas in the later phase, the fluorescence declined (Fig. 6B, arrow). It may be that the increase in fluorescence was associated with the binding of substrate to the active center, which involves voltage-sensor activation and movement of the gating, 515 and Cα2 loops, whereas the decrease in fluorescence may be associated with a conformation change to catalyze dephosphorylation of phosphoinositides, which is a process occurring just after substrate binding (Fig. 7C). An operation of the Cα2 loop may correspond to each step of a catalytic cycle of the phosphatase, such as an opening of the active center and a removal of the phosphate from the substrate. Future studies of analyzing correlation between detection of local structural change and substrate turnover will be necessary to test this idea. Detailed analyses using the fluorescent unnatural amino acid in Ci-VSP will also lead to understanding conserved molecular mechanisms shared by other phosphatases, such as PTEN, which has a high similarity to the catalytic region of Ci-VSP.

Methods

cDNAs.

The cDNA Ci-VSP was identical to that used in our earlier work (4–6). A Kir3.2d cDNA was a gift from Yoshihisa Kurachi (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). G protein β- and γ-plasmids were provided by Toshihide Nukada (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan). pAnap, a plasmid that encodes tRNA and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, was kindly provided by Peter G. Schultz (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Electrophysiology.

Electrophysiology and fluorescence measurements were performed with a two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) as we did previously (5, 6). ND 96 solution (5 mM Hepes, 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) was used as the bath solution for measurements of fluorescence and sensing currents. For measurement of the sensing current, leak currents and the current for charging the cell capacitance were cancelled using the P/−10 or P/−5 protocol, in which a step pulse for subtraction was applied from the holding potential. The sensing charge was calculated by the integration of on- or off-sensing current. The holding potential was −60 mV unless otherwise noted.

Incorporation and Measurement of Anap Fluorescence.

All experiments were performed in compliance with the Animal Research Committees of the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University. Xenopus oocytes were prepared as described previously (4–6). For Anap (FutureChem) incorporation into Ci-VSP, 20 nL of pAnap solution (10 ng/μL) was injected into the nucleus of the oocytes. One day later, 1 mM Anap and cRNA encoding Ci-VSP in which the target site was mutated to a TAG codon were mixed 1:1, and the 20 nL of the mixture was injected into the oocytes. The oocytes were then incubated for 2 d in the dark. Oocytes were imaged using an IX71 inverted microscope (Olympus) equipped with a 10× 0.3 N.A. objective lens and a mercury lamp under TEVC. Fluorescence was detected using one or two PMTs (H10722-20; Hamamatsu Photonics). The output of the PMTs was digitized using the AD/DA converter (Digidata1440A) shared with the TEVC setup. Fluorescence changes were elicited by a set of test pulses of 20-mV increments except for the prepulse experiment. The set of fluorescence data was averaged from 4 to 16 times. There was no time interval between the set of test pulses. The fluorescence data of the experiment with preconditioning pulse (the protocol shown in Fig. S10D) were also averaged by repeating from 4 to 16 times. All fluorescence data were digitally filtered at 300 Hz. DPA was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry for use in the FRET experiments.

Note Added in Proof.

After the paper was accepted, a paper characterizing voltage dependence of phosphatase activity of VSP shared among four subreactions toward distinct phosphoinositides was published (34).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter G. Schultz (The Scripps Research Institute) for giving us the pAnap plasmid; Dr. Yoshihisa Kurachi (Osaka University) for providing the Kir3.2d plasmid; Dr. Mari Sasaki for providing original data of the sensing current of wild-type Ci-VSP measured by the cut-open oocyte method; Dr. Masafumi Minoshima (Osaka University) for giving us advice for the Anap experiment; Dr. Fumihito Ono (Osaka Medical College) for encouragement and critical reading of the manuscript; and Dr. Yasushi Sako (RIKEN) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (to S.S. and Y.O.) and Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology from the Japan Science Technology Agency (Y.O).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604218113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sasaki M, Takagi M, Okamura Y. A voltage sensor-domain protein is a voltage-gated proton channel. Science. 2006;312(5773):589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1122352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsey IS, Moran MM, Chong JA, Clapham DE. A voltage-gated proton-selective channel lacking the pore domain. Nature. 2006;440(7088):1213–1216. doi: 10.1038/nature04700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tombola F, Pathak MM, Isacoff EY. Voltage-sensing arginines in a potassium channel permeate and occlude cation-selective pores. Neuron. 2005;45(3):379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murata Y, Iwasaki H, Sasaki M, Inaba K, Okamura Y. Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature. 2005;435(7046):1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature03650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murata Y, Okamura Y. Depolarization activates the phosphoinositide phosphatase Ci-VSP, as detected in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing sensors of PIP2. J Physiol. 2007;583(Pt 3):875–889. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakata S, Hossain MI, Okamura Y. Coupling of the phosphatase activity of Ci-VSP to its voltage sensor activity over the entire range of voltage sensitivity. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 11):2687–2705. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.208165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutua J, et al. Functional diversity of voltage-sensing phosphatases in two urodele amphibians. Physiol Rep. 2014;2(7):e12061. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okamura Y, Murata Y, Iwasaki H. Voltage-sensing phosphatase: Actions and potentials. J Physiol. 2009;587(3):513–520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JO, et al. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: Implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell. 1999;99(3):323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgescu MM, et al. Stabilization and productive positioning roles of the C2 domain of PTEN tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):7033–7038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalli AC, Devaney I, Sansom MS. Interactions of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) proteins with phosphatidylinositol phosphates: Insights from molecular dynamics simulations of PTEN and voltage sensitive phosphatase. Biochemistry. 2014;53(11):1724–1732. doi: 10.1021/bi5000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamura Y, Dixon JE. Voltage-sensing phosphatase: Its molecular relationship with PTEN. Physiology (Bethesda) 2011;26(1):6–13. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00035.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villalba-Galea CA, Miceli F, Taglialatela M, Bezanilla F. Coupling between the voltage-sensing and phosphatase domains of Ci-VSP. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134(1):5–14. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohout SC, et al. Electrochemical coupling in the voltage-dependent phosphatase Ci-VSP. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(5):369–375. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobiger K, Utesch T, Mroginski MA, Friedrich T. Coupling of Ci-VSP modules requires a combination of structure and electrostatics within the linker. Biophys J. 2012;102(6):1313–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobiger K, Utesch T, Mroginski MA, Seebohm G, Friedrich T. The linker pivot in Ci-VSP: the key to unlock catalysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuda M, et al. Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-like region of Ciona intestinalis voltage-sensing phosphatase provides insight into substrate specificity and redox regulation of the phosphoinositide phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(26):23368–23377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, et al. A glutamate switch controls voltage-sensitive phosphatase function. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(6):633–641. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakata S, Okamura Y. Phosphatase activity of the voltage-sensing phosphatase, VSP, shows graded dependence on the extent of activation of the voltage sensor. J Physiol. 2014;592(5):899–914. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.263640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimm SS, Isacoff EY. Allosteric substrate switching in a voltage-sensing lipid phosphatase. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(4):261–267. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatterjee A, Guo J, Lee HS, Schultz PG. A genetically encoded fluorescent probe in mammalian cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(34):12540–12543. doi: 10.1021/ja4059553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HS, Guo J, Lemke EA, Dimla RD, Schultz PG. Genetic incorporation of a small, environmentally sensitive, fluorescent probe into proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(36):12921–12923. doi: 10.1021/ja904896s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summerer D, et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent amino acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(26):9785–9789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Xie J, Schultz PG. A genetically encoded fluorescent amino acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(27):8738–8739. doi: 10.1021/ja062666k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsutsui H, et al. Improved detection of electrical activity with a voltage probe based on a voltage-sensing phosphatase. J Physiol. 2013;591(18):4427–4437. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chanda B, et al. A hybrid approach to measuring electrical activity in genetically specified neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1619–1626. doi: 10.1038/nn1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chanda B, Asamoah OK, Blunck R, Roux B, Bezanilla F. Gating charge displacement in voltage-gated ion channels involves limited transmembrane movement. Nature. 2005;436(7052):852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature03888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taraska JW, Zagotta WN. Structural dynamics in the gating ring of cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(9):854–860. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsutsui H, Jinno Y, Tomita A, Okamura Y. Optically detected structural change in the N-terminal region of the voltage-sensor domain. Biophys J. 2013;105(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falkenburger BH, Dickson EJ, Hille B. Quantitative properties and receptor reserve of the DAG and PKC branch of G(q)-coupled receptor signaling. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141(5):537–555. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suh BC, Leal K, Hille B. Modulation of high-voltage activated Ca(2+) channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Neuron. 2010;67(2):224–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castle PM, Zolman KD, Kohout SC. Voltage-sensing phosphatase modulation by a C2 domain. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:63. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurokawa T, et al. 3′ Phosphatase activity toward phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate [PI(3,4)P2] by voltage-sensing phosphatase (VSP) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(25):10089–10094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203799109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keum D, Kruse M, Kim D-I, Hille B, Suh B-C. Phosphoinositide 5- and 3-phosphatase activities of a voltage-sensing phosphatase in living cells show identical voltage dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. May 24, 2016;113(26):E3686–E3695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606472113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]