Significance

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infects hepatocytes via an intricate series of interactions with the host cell machinery. Recently, we identified E-cadherin as a host dependency factor mediating HCV entry through integrative functional genomics studies. E-cadherin silencing restricted HCV entry and infection in hepatocytes. Mechanistic studies demonstrated that E-cadherin is a prerequisite for the cell-surface localization of claudin-1 and OCLN, two major HCV coreceptors. Moreover, HCV-induced loss of E-cadherin is associated with cancer-related cellular changes. Our study suggests that a dynamic interplay among E-cadherin, tight junction coreceptors, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition exists and plays an important role in regulating HCV entry. E-cadherin thereby represents a missing host factor in the comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms and cellular regulatory events underlying HCV entry and pathogenesis.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, viral entry, E-cadherin, tight junction, epithelial–mesenchymal transition

Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) enters the host cell through interactions with a cascade of cellular factors. Although significant progress has been made in understanding HCV entry, the precise mechanisms by which HCV exploits the receptor complex and host machinery to enter the cell remain unclear. This intricate process of viral entry likely depends on additional yet-to-be-defined cellular molecules. Recently, by applying integrative functional genomics approaches, we identified and interrogated distinct sets of host dependencies in the complete HCV life cycle. Viral entry assays using HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpps) of various genotypes uncovered multiple previously unappreciated host factors, including E-cadherin, that mediate HCV entry. E-cadherin silencing significantly inhibited HCV infection in Huh7.5.1 cells, HepG2/miR122/CD81 cells, and primary human hepatocytes at a postbinding entry step. Knockdown of E-cadherin, however, had no effect on HCV RNA replication or internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-mediated translation. In addition, an E-cadherin monoclonal antibody effectively blocked HCV entry and infection in hepatocytes. Mechanistic studies demonstrated that E-cadherin is closely associated with claudin-1 (CLDN1) and occludin (OCLN) on the cell membrane. Depletion of E-cadherin drastically diminished the cell-surface distribution of these two tight junction proteins in various hepatic cell lines, indicating that E-cadherin plays an important regulatory role in CLDN1/OCLN localization on the cell surface. Furthermore, loss of E-cadherin expression in hepatocytes is associated with HCV-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), providing an important link between HCV infection and liver cancer. Our data indicate that a dynamic interplay among E-cadherin, tight junctions, and EMT exists and mediates an important function in HCV entry.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV), a member of the Hepacivirus genus in the Flaviviridae family, is an enveloped, single-stranded and positive-sense RNA virus that infects humans and other higher primates, with a selective tropism to the liver. The virus is estimated to infect 2.8% of the world’s population (1), and has evolved into a major causative agent of end-stage liver diseases, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2). Chronic hepatitis C is also the leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States (3). To date, a protective vaccine is not available. Current therapeutic regimens applying direct-acting antivirals with or without ribavirin have made it possible to cure the majority of patients with HCV (4).

HCV infection gains chronicity in ∼75–85% of patients, facilitated by various viral mechanisms to evade host immune responses and exploit the cellular machinery (5). The replication cycle of HCV in the host cell consists of multiple sequential steps, beginning with the lipo-viro-particle binding and entry, followed by viral RNA translation and replication, packaging and assembly of the virion, and finally secretion from host cells (6, 7). Each of these steps relies on extensive interactions with cellular factors and molecular pathways (8, 9). Identification and characterization of these HCV host dependencies may provide not only critical insights into mechanisms of HCV-induced disease, but also potential intervention and prophylactic targets.

HCV entry plays a central role in cell tropism and species specificity. The highly coordinated entry process involves a variety of cellular molecules—termed HCV entry factors—including the tetraspanin CD81 (10), scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) (11), the tight junction proteins claudin-1 (CLDN1) and occludin (OCLN) (12, 13), the receptor tyrosine kinases EGFR and ephrin receptor A2 (14), the cholesterol transporter Niemann–Pick C1-like 1 (15), and the iron-uptake receptor transferrin receptor 1 (16). These cell-surface molecules have been shown to interact with viral proteins or particles to facilitate HCV entry.

Although great advances have been achieved in elucidating the HCV entry pathway, the precise mechanisms by which HCV exploits the aforementioned cellular signals and gains entry to the host cell remain unclear. Moreover, the highly complex and dynamic entry process most likely requires additional yet-to-be-defined molecules, interacting simultaneously or in sequence, to bind, endocytose, and internalize the virus. Recently, to interrogate global HCV–host interactions in the entire viral life cycle, we conducted an unbiased, genome-wide siRNA screen, followed by targeted screens applying integrative functional genomics and systems virology approaches (8, 17). Five previously unappreciated HCV host dependencies were identified as putative viral entry factors, and these include CDH1 (E-cadherin), a major adherens junction protein. In this study, we investigated the precise role and mechanism of action of E-cadherin in modulating HCV infection. We demonstrated that E-cadherin expression is specifically required for HCV entry. Loss of E-cadherin in hepatocytes resulted in aberrant cell surface distribution of the tight junction proteins CLDN1 and OCLN—two well-characterized HCV entry factors. Loss of E-cadherin is also a hallmark of HCV-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a cellular mechanism that presumably restricts HCV entry to inhibit viral superinfection and mediates the progression of HCV-induced liver diseases.

Results

E-Cadherin Is Required for HCV Infection.

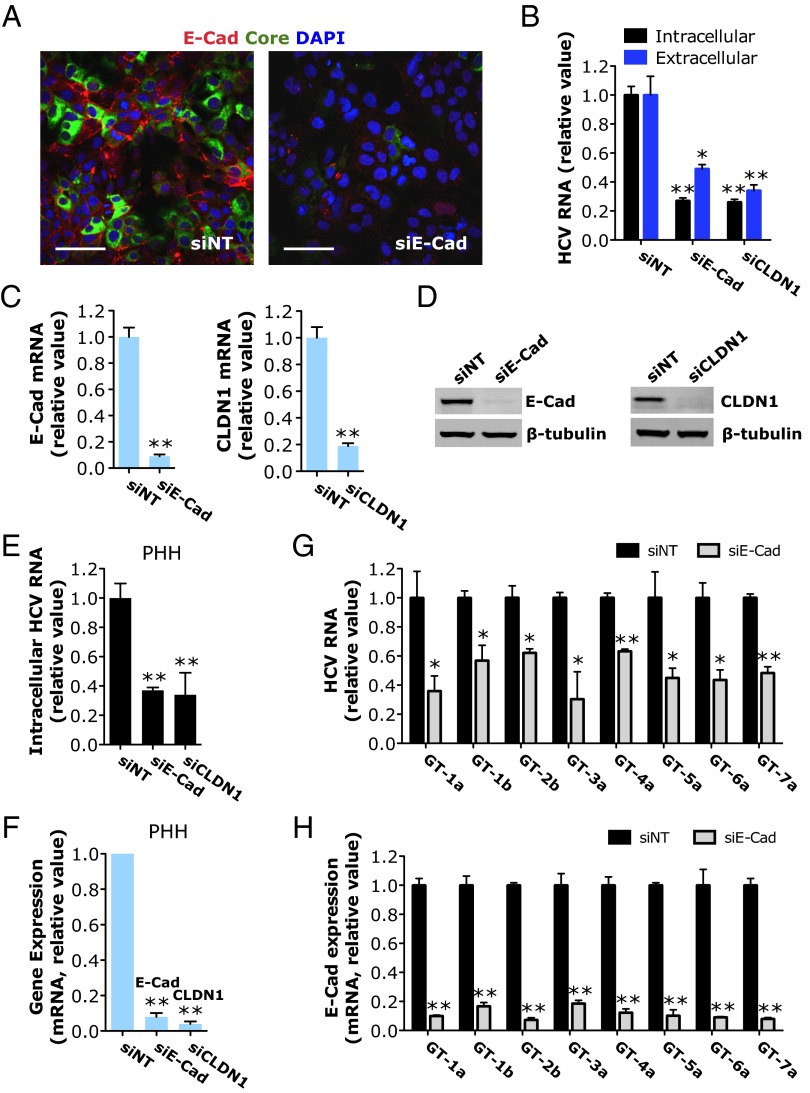

To validate the function of E-cadherin in modulating HCV infection, we performed various virologic assays. Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with E-cadherin siRNA before infection with HCV. Depletion of E-cadherin expression by siRNA drastically inhibited HCV core protein production (Fig. 1A). E-cadherin silencing, like silencing of CLDN1, a previously known HCV entry factor (12), significantly reduced HCV RNA levels in cells and in the medium (Fig. 1B). E-cadherin or CLDN1 mRNA and protein levels were substantially repressed by SMARTpool siRNA treatment without inducing apparent cytotoxicity (Fig. 1 C and D and Fig. S1A). The phenotype-specific role of E-cadherin in HCV infection was confirmed by testing four individual siRNAs targeting various regions of the E-cadherin sequence. All four E-cadherin siRNAs inhibited HCV infection to varying extents, which correlated with the knockdown efficiencies at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. S1 B–D). As expected, treatment of cells with four CLDN1 individual siRNAs of the SMARTpool blocked HCV infection in proportion to their silencing potencies (Fig. S1 E–G). In primary human hepatocytes (PHHs), E-cadherin or CLDN1 knockdown resulted in marked inhibition of HCV infection (Fig. 1 E and F). The proviral effect of E-cadherin is pan-genotypic. In Huh7.5.1 cells, depletion of E-cadherin significantly inhibited the infection of all HCV major genotypes (Fig. 1 G and H).

Fig. 1.

HCV infection is dependent on E-cadherin (E-Cad) expression. (A) Confocal microscopic imaging of CDH1 (red) and HCV core (green) expression in the nontargeting control siRNA (siNT)- or siE-cadherin–treated Huh7.5.1 cells 48 h after HCV infection. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) (B) Effects of siRNA-mediated E-cadherin or CLDN1 silencing on HCV RNA levels in Huh7.5.1 cells or the culture supernatant. (C and D) Knockdown efficiency of E-cadherin or CLDN1 siRNA. E-cadherin and CLDN1 mRNA (C) or protein (D) levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR) or Western blot, respectively. β-Tubulin served as a loading control for Western blot. (E and F) Efficacy of E-cadherin or CLDN1 siRNA in restricting HCV infection (E) or silencing target gene (F) in PHHs. (G and H) E-cadherin knockdown inhibits HCV infection of different genotypes. (G) Quantification of intracellular HCV RNA levels in siNT- or siE-cadherin–treated Huh7.5.1 cells infected with HCV of various genotypes. (H) Knockdown efficiency of E-cadherin siRNA in the aforementioned cells. (B–H) All values were normalized to siNT (as 1) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

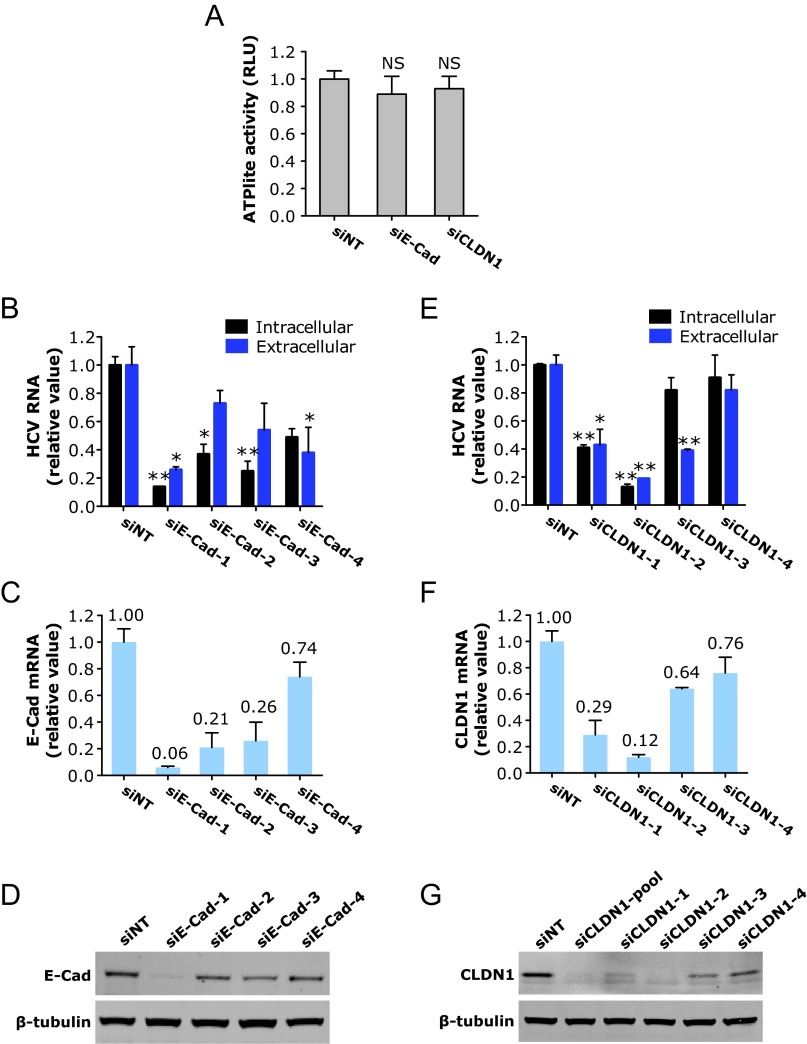

Fig. S1.

Phenotype-specific role of E-cadherin (E-Cad) or CLDN1 knockdown in HCV infection. (A) Viability of cells treated with E-cadherin or CLDN1 siRNA. Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with each indicated siRNAs at a 50 nM final concentration for 72 h, and ATPlite assays that examine cytotoxicity of the siRNAs were subsequently conducted. (B and C) Quantification of intracellular and extracellular HCV RNA levels from Huh7.5.1 cells treated with various individual E-cadherin (B) or CLDN1 (C) siRNAs. (D–G) Knockdown efficiencies of individual E-cadherin or CLDN1 siRNAs. E-cadherin and CLDN1 mRNA (D and E) or protein (F and G) levels were measured by Q-PCR or Western blot, respectively. β-Tubulin served as a loading control for Western blot. (A–E) All values were normalized to siNT (as 1) and represent the mean ± SD [n = 5 (A) or n = 3 (B–E)]. (A) NS, not statistically significant. (B and C) Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). (D and E) Relative mRNA levels (comparing with siNT, as 1) of E-cadherin (D) or CLDN1 (E) upon various siRNA treatments are labeled on the top of each bar.

E-Cadherin Specifically Modulates HCV Entry at a Postbinding Step.

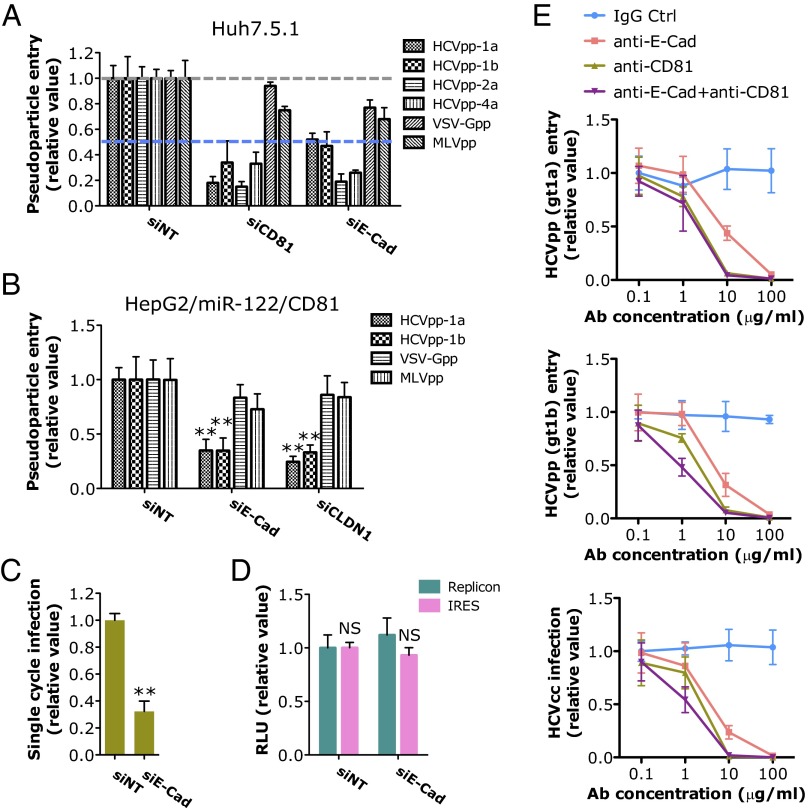

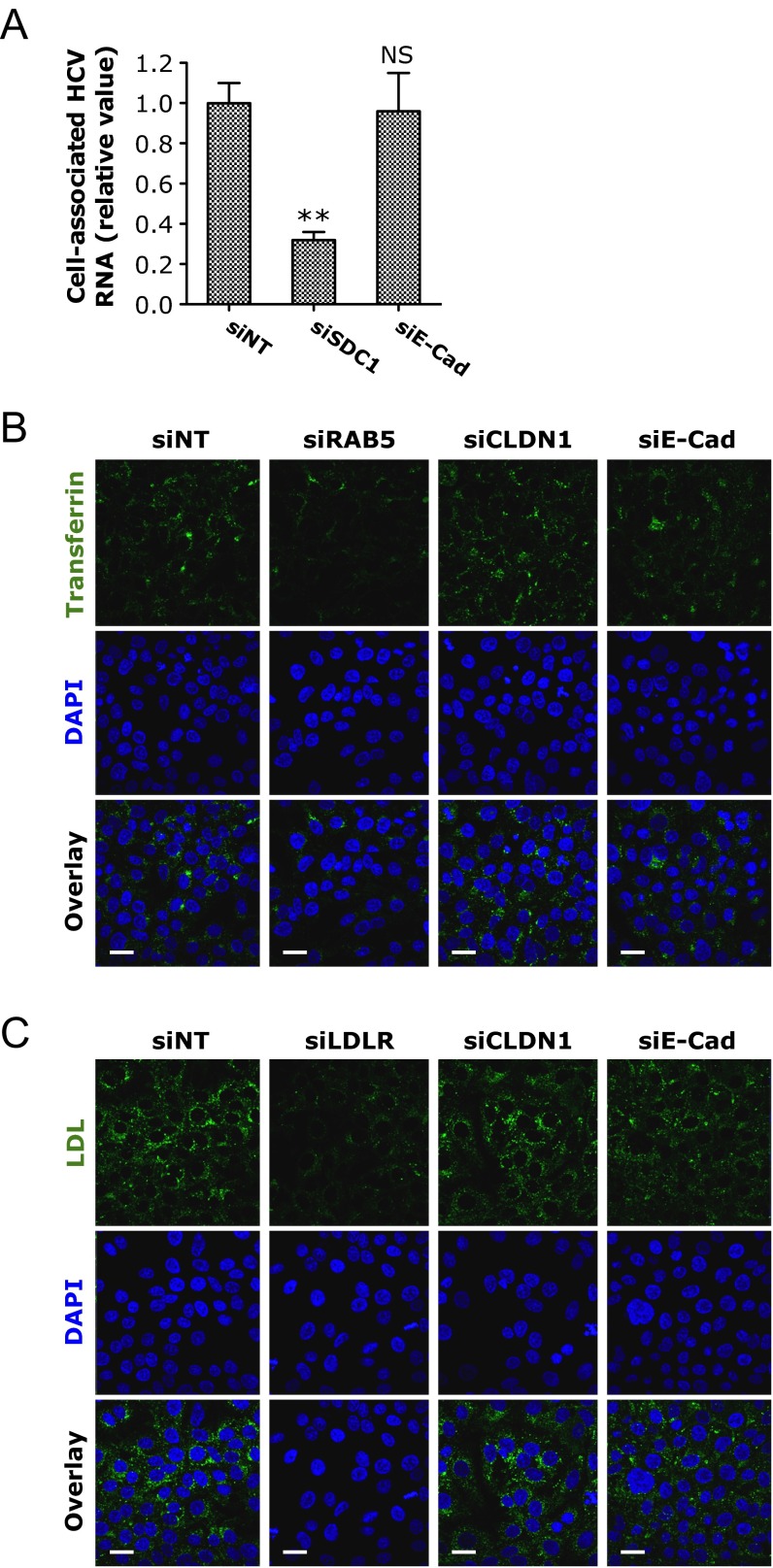

We next examined the steps of the HCV life cycle that are affected by E-cadherin expression. Viral entry assays were conducted by using HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpps) of various genotypes and other pseudoviruses including VSV-Gpp, a pseudotyped virus bearing the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein, and the MLV pseudoparticle (MLVpp) in Huh7.5.1 cells. Silencing of E-cadherin by siRNA considerably blocked the entry of HCVpps but not that of VSV-Gpps or MLVpps (Fig. 2A), suggesting that E-cadherin expression is uniquely required for HCV entry. Similarly, in HepG2/miR122/CD81 cells (18), E-cadherin depletion significantly inhibited HCVpp infection, but did not exert noticeable effects on VSV-Gpp or MLVpp infection (Fig. 2B), confirming the specificity of E-cadherin in modulating HCV entry. To examine whether E-cadherin is involved in the initial attachment or downstream steps in the viral entry process, we conducted an HCV infectious cell culture system (HCVcc) binding assay. SiRNA-mediated knockdown of E-cadherin had no effect on HCVcc binding at 4 °C (Fig. S2A). In contrast, silencing of SDC1, a previously reported host-dependency factor that mediates HCV attachment (19), significantly inhibited HCV binding (Fig. S2A). These data indicate that E-cadherin acts on a postbinding step during HCV entry. Next, we performed transferrin and LDL-uptake assays and demonstrated that E-cadherin is not involved in the much later-stage clathrin-mediated endocytosis of HCV (Fig. S2 B and C). E-cadherin knockdown by siRNA nevertheless decreased the infection of single-round infectious HCV (HCVsc) in the single cycle infection assay that represents a single-round packaged replicon transduction assay (20, 21), reinforcing the importance of this gene at an early step of the HCV life cycle (Fig. 2C). Silencing of E-cadherin, however, had no effect on HCV RNA replication or internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-mediated translation, as shown by HCV replicon or IRES assays (Fig. 2D). In addition, the anti–E-cadherin mAb blocked the infection of HCVpp and HCVcc in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

E-cadherin (E-Cad) is specifically required for HCV entry. (A and B) The effects of siRNA-mediated gene silencing on infection of firefly luciferase-encoded pseudotyped viruses bearing HCV of various genotypes, VSV or MLV envelopes in Huh7.5.1 cells (A) or HepG2/miR-122/CD81 cells (B). The previously known HCV entry factors CD81 (A) and CLDN1 (B) were used as positive controls. (C) Effect of E-cadherin knockdown on HCVsc infection. (D) HCV replicon and IRES assays of Huh7.5.1 cells transfected with nontargeting control or E-cadherin siRNA. (A–D) All values, based on luciferase readings, were normalized to siNT (as 1) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (**P < 0.01); NS, not significant. (E) Effects of anti–E-cadherin blocking antibody on HCV infection. Huh7.5.1 cells were preincubated with increasing concentrations of anti–E-cadherin, anti-CD81, or isotype IgG control (Ctrl) mAbs for 2 h at 37 °C before infection with HCVpp-1a (Upper), HCVpp-1b (Middle), or HCVcc (HCV P7-Luc; Lower). After 48 h, viral infection was determined by measuring the luciferase activities. Results are shown as relative values compared with IgG control administered at 0.1 µg/mL (as 1) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5).

Fig. S2.

E-cadherin (E-Cad) is not involved in HCV attachment or endocytosis. (A) HCV binding assay. Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with each indicated siRNA for 72 h and subsequently incubated with HCV at 4 °C for 2 h. Cells were then washed with cold PBS solution to remove the unbound virus. Intracellular HCV RNA levels were determined by Q-PCR. siRNA targeting SDC1, a previously reported host dependency factor that mediates HCV attachment (19), was used as a positive control. Values were normalized to siNT (as 1) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). (B and C) Confocal microscopic analyses of transferrin endocytosis (B) and LDL uptake (C) in Huh7.5.1 cells depleted of various indicated HCV entry factors by siRNA treatment. Transferrin (B) and LDL (C) are labeled in green. (Scale bars: 20 μm.) SiRNAs against RAB5, a host-dependency factor involved in HCV clathrin-mediated endocytosis (52), was used as a positive control for transferrin endocytosis assay. LDL receptor siRNA (siLDLR) was used as a positive control for LDL-uptake assay.

E-Cadherin Regulates CLDN1 and OCLN Cell Surface Distribution.

To explore the mechanism of E-cadherin–mediated HCV entry, we first showed that E-cadherin depletion in Huh7.5.1 cells did not alter the mRNA or protein levels of four major HCV entry factors—CLDN1, OCLN, CD81, and SR-BI (Fig. S3 A and B)—suggesting that the function of E-cadherin in modulating HCV entry is not directly related to affecting the expression levels of these known entry factors. By confocal microscopy, E-cadherin appeared to be closely associated with CLDN1 and OCLN on the cell membrane (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, silencing of E-cadherin in these cells drastically reduced distribution of CLDN1 and OCLN on the cell surface (Fig. 3A). In contrast, localization of zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1)—another tight junction protein—and CD81 and SR-BI remained unchanged upon E-cadherin siRNA treatment (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4A). This effect on CLDN1 localization appeared to be E-cadherin–specific, as knocking down other known (CD81) or recently defined entry factors (CHKA, CYBA, SMAD6, and RAC1) (8) did not decrease CLDN1 cell membrane expression (Fig. S4B). Similar E-cadherin–dependent CLDN1/OCLN cell membrane distribution was observed in HepG2/miR122/CD81 cells (Fig. 3B), further confirming that E-cadherin plays an important regulatory role in CLDN1/OCLN localization on the cell surface.

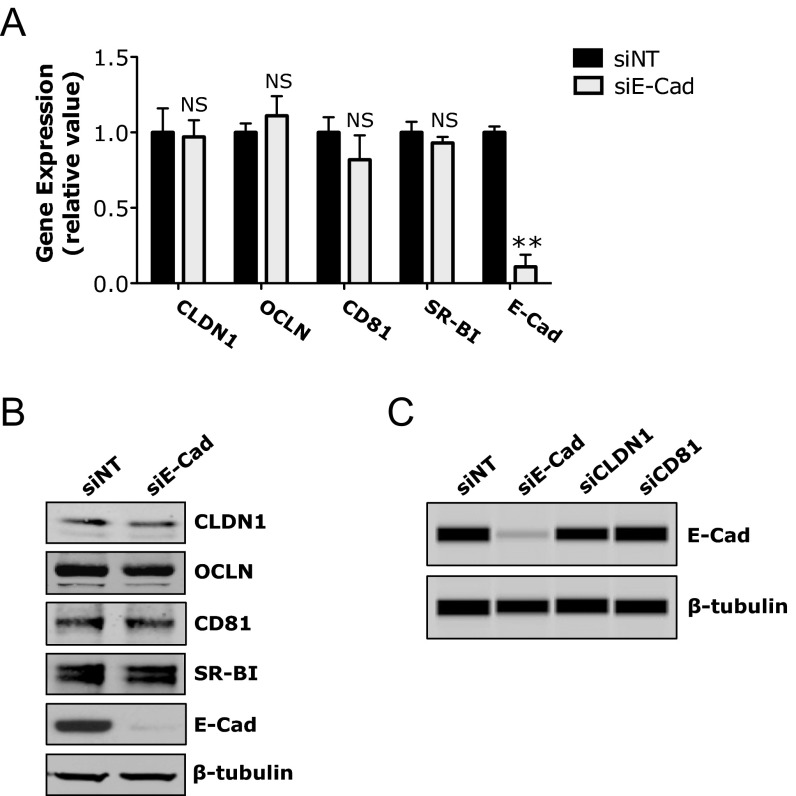

Fig. S3.

Effects of silencing HCV entry factors on the expression of other viral entry factors. (A and B) Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with siNT or E-cadherin (E-Cad) siRNA for 72 h, and mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels of the indicated HCV entry factors were determined by Q-PCR or Western blot, respectively. (C) Cells were transfected with various indicated siRNAs for 72 h and then examined for E-cadherin expression by Western blot. (A) All values were normalized to siNT (as 1) and represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). NS, not statistically significant. (B and C) β-Tubulin was used as a loading control.

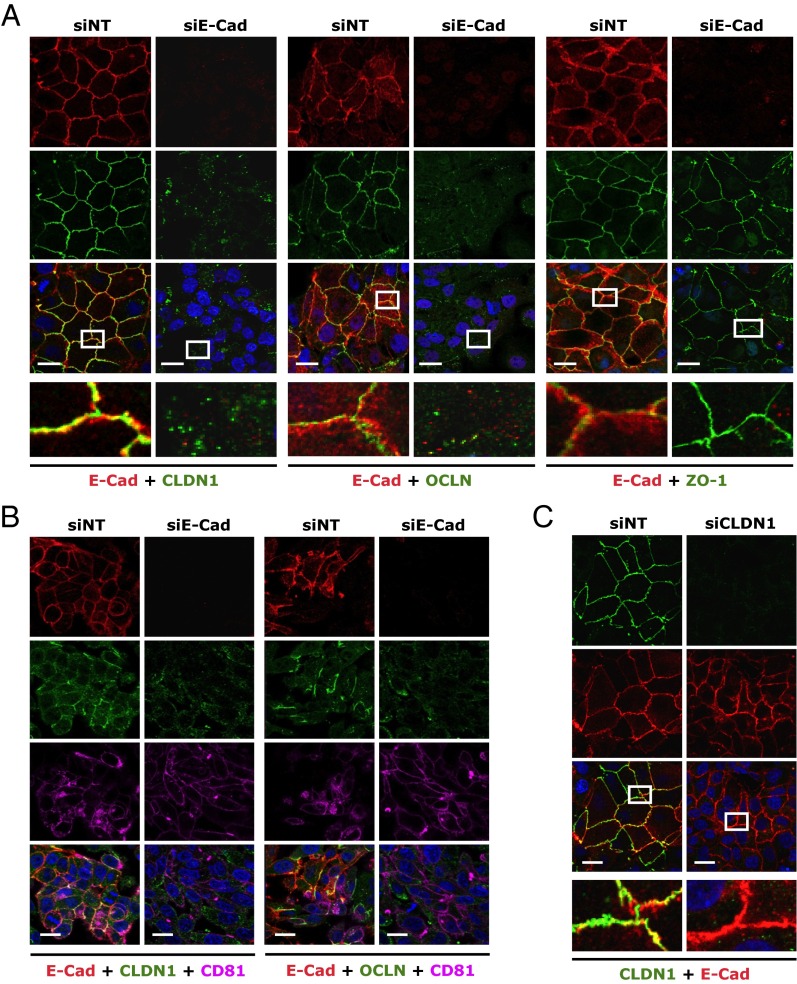

Fig. 3.

E-cadherin (E-Cad) is required for proper CLDN1 and OCLN cell-surface localization. (A) Colocalization analyses of E-cadherin (red) with CLDN1, OCLN, or ZO-1 (green) in Huh7.5.1 cells transfected with siNT or E-cadherin siRNA. Immunostaining and subsequent confocal microscopic imaging were performed at 72 h after siRNA treatment. (B) Effect of E-cadherin silencing on cell membrane distribution of CLDN1 and OCLN in HepG2/miR-122/CD81 cells. Red, E-cadherin; green, CLDN1 or OCLN; magenta, CD81. (C) Effect of CLDN1 silencing on E-cadherin expression and subcellular localization. Green, CLDN1; red, E-cadherin. (A and C) Magnified view (white box) of each merged image is shown at the bottom. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

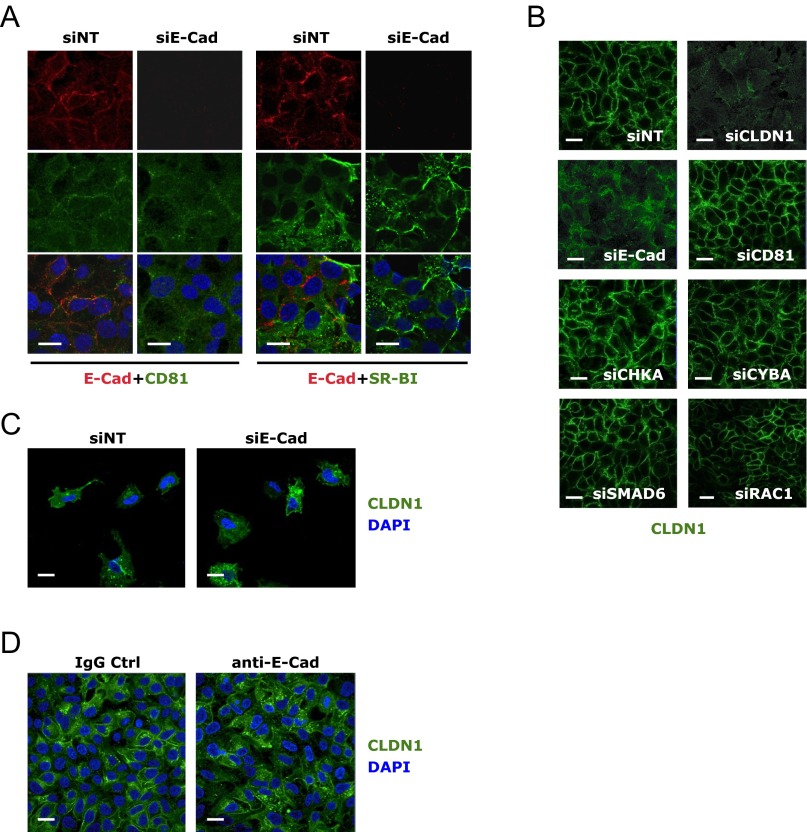

Fig. S4.

Subcellular localization of E-cadherin (E-Cad) and HCV coreceptors. (A) Confocal microscopic imaging of E-cadherin (red) and CD81 or SR-BI (green) localization in Huh7.5.1 cells treated with siNT or E-cadherin siRNA. (B) Effect of siRNA targeting various HCV entry factors on CLDN1 (green) cell membrane localization. (C) CLDN1 (green) and E-cadherin (red) expression and localization in sparsely seeded Huh7.5.1 cells. (D) Effect of anti–E-cadherin mAb treatment on CLDN1 expression. Huh7.5.1 cells were incubated with anti–E-cadherin or isotype IgG control (Ctrl) mAb at the concentration of 100 μg/mL for 24 h at 37 °C and subsequently examined for CLDN1 expression by immunofluorescence/confocal microscopy. A rabbit polyclonal antibody was used for detection of CLDN1 expression. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

The requirement of E-cadherin expression for CLDN1 cell surface distribution occurs only in the context of cell-to-cell contact, as the subcellular localization of CLDN1 is not affected by E-cadherin silencing in sparsely grown cells (Fig. S4C). In addition, treating Huh7.5.1 cells with anti–E-cadherin monoclonal antibody did not cause any apparent reduction in CLDN1 cell membrane distribution (Fig. S4D), implying that the anti–E-cadherin antibody interferes with the subsequent function of the CDH1–CLDN1–OCLN complex in HCV entry.

CLDN1 and OCLN are involved in the postbinding step of HCV entry, although the mechanism governing this process remains elusive (12, 13, 22). As expected, silencing of CLDN1 by siRNA significantly inhibited HCV infection in Huh7.5.1 cells and PHHs (Fig. 1 B–F and Fig. S1 E–G). Whereas silencing of E-cadherin disrupted the localization of CLDN1, silencing of CLDN1, on the contrary, had no effect on the subcellular localization or overall expression level of E-cadherin (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3C).

HCV Infection Represses E-Cadherin Expression and Induces EMT.

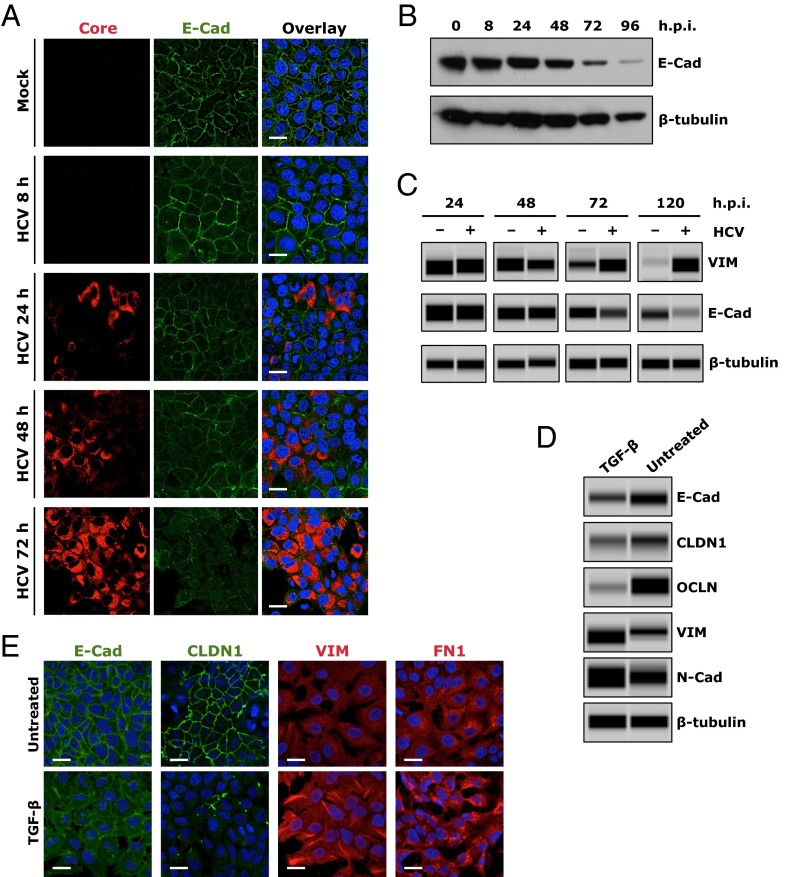

Aberrant expression of E-cadherin is considered to be a fundamental event in EMT, a process by which epithelial cells lose their cell polarity and adhesions junctions, thereby acquiring more migratory and invasive mesenchymal properties (23). EMT constitutes an important mechanism in wound healing, organ fibrosis, and the initiation of cancer metastasis. To study the effect of HCV infection on E-cadherin expression and EMT, we showed that, in HCV-infected cells positive for core or NS5A, the expression and cell-surface distribution of E-cadherin were considerably diminished (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5). As shown by Western blot, E-cadherin expression was also noticeably reduced as the HCV infection progressed (Fig. 4B). We then investigated whether the down-regulation of E-cadherin by HCV is indeed associated with EMT in Huh7.5.1 cells. We showed that the expression level of vimentin (VIM), a major mesenchymal marker, was markedly induced after HCV infection, whereas E-cadherin, the epithelial marker, was down-regulated in HCV-infected cells (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Induction of EMT by HCV infection or TGF-β treatment. (A and B) Effect of HCV infection on E-cadherin (E-cad) expression in Huh7.5.1 cells at various time points postinfection, examined by immunofluorescence/confocal microscopy (A) or Western blot (B). (A) Levels of HCV infection were determined by core staining (red). (C) Effect of HCV infection on expression of VIM, a cellular EMT marker. Cells were mock-infected or infected with HCV, and harvested at various indicated time points, before being examined for E-cadherin or VIM expression by Western blot. (D and E) TGF-β treatment induces EMT in Huh7.5.1 cells. Cells were incubated in the absence (untreated) or presence of TGF-β (0.1 ng/mL) for 24 h, and expression levels of E-cadherin, CLDN1, OCLN, and multiple EMT markers were determined by Western blot (E). E-cadherin, CLDN1, VIM, and FN1 expression levels were also determined by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (E). β-Tubulin was used as a loading control in B–D. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

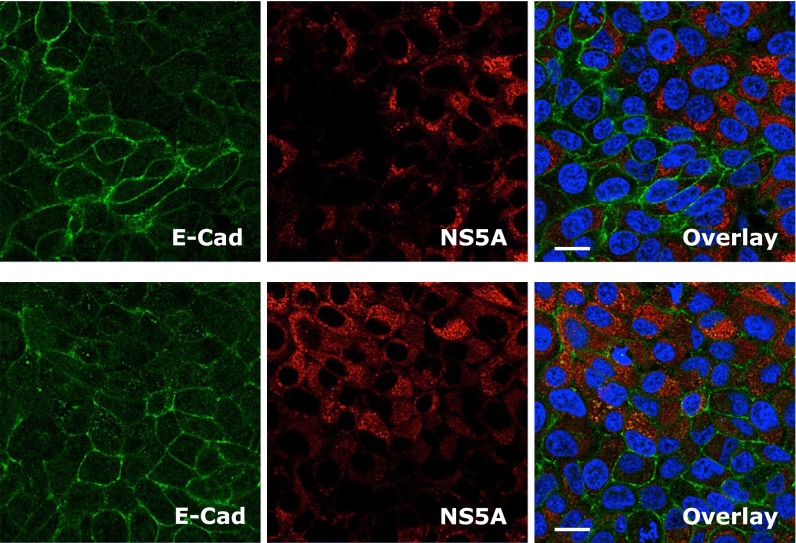

Fig. S5.

Effect of HCV infection on E-cadherin (E-Cad) expression. Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with HCV for 48 h, and subsequently examined by immunofluorescence/confocal microscopy for NS5A (red) or E-cadherin (green) expression. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

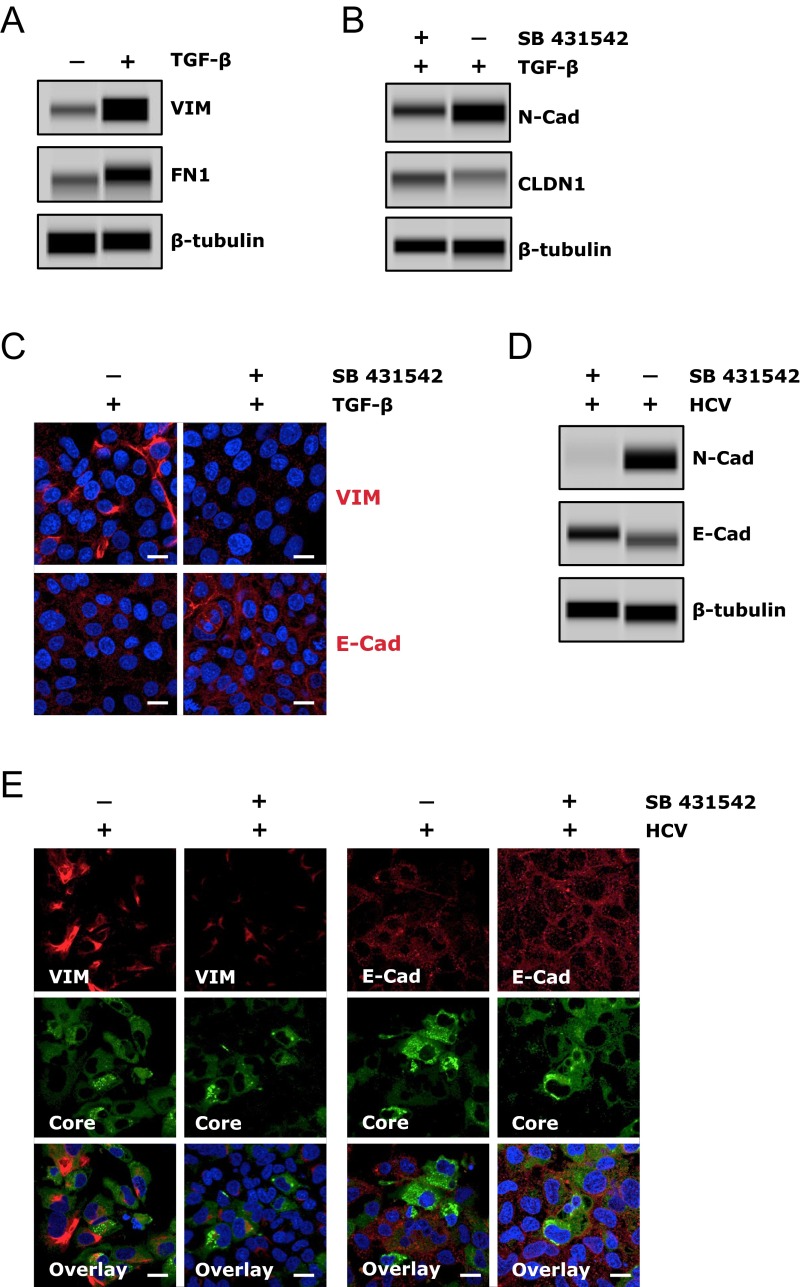

TGF-β signaling is an important and well-recognized cellular inducer of EMT. Interestingly, HCV core and envelope proteins have been shown to trigger EMT via activation of TGF-β (24). We demonstrated that TGF-β treatment of Huh7.5.1 cells resulted in the loss of E-Cad, CLDN1, and OCLN and subsequent induction of EMT, as evidenced by elevated expression of the mesenchymal markers VIM, fibronectin (FN1), and N-cadherin in these cells (Fig. 4 D and E and Fig. S6A). These effects of TGF-β can be efficiently blocked by adding SB 431542, a bona fide TGF-β inhibitor (Fig. S6 B and C). Interestingly, when cells were treated with SB 431542, HCV-triggered loss of E-cadherin and induction of EMT was considerably abrogated (Fig. S6 D and E), suggesting that the function of HCV in regulating E-cadherin expression and inducing EMT relies, at least partially, on TGF-β activation. The induction of TGF-β by HCV has been previously reported (25). In addition, treatment of cells with E-cadherin blocking antibody had no effect on VIM and FN1 expression (Fig. S7), indicating that the inhibitory effect of the anti–E-cadherin mAb on HCV entry is mediated by another mechanism distinct from EMT induction.

Fig. S6.

HCV-mediated E-cadherin (E-Cad) down-regulation and EMT induction depends on TGF-β activation. (A) TGF-β treatment induces EMT in Huh7.5.1 cells. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of TGF-β (0.1 ng/mL) for 24 h, and protein levels of EMT markers VIM and FN1 were determined by Western blot. (B and C) TGF-β inhibitor treatment diminishes the effects of TGF-β on EMT and E-cadherin/CLDN1 expression. Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with the TGF-β inhibitor SB 431542 at a concentration of 10 μM for 3 h, and then treated with TGF-β at 0.1 ng/mL. Cells were harvested 24 h after TGF-β treatment and subjected to Western blot (B) or immunofluorescence/confocal microscopy (C). (D and E) TGF-β inhibitor SB 431542 abrogates HCV-mediated induction of EMT and suppression of E-cadherin expression. Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with SB 431542 (10 μM) for 3 h and then infected with HCV. After 4 d, cells were harvested and subject to Western blot (D) or immunostaining and confocal microscopy (E). (A, B, and D) β-Tubulin served as a loading control for Western blot. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

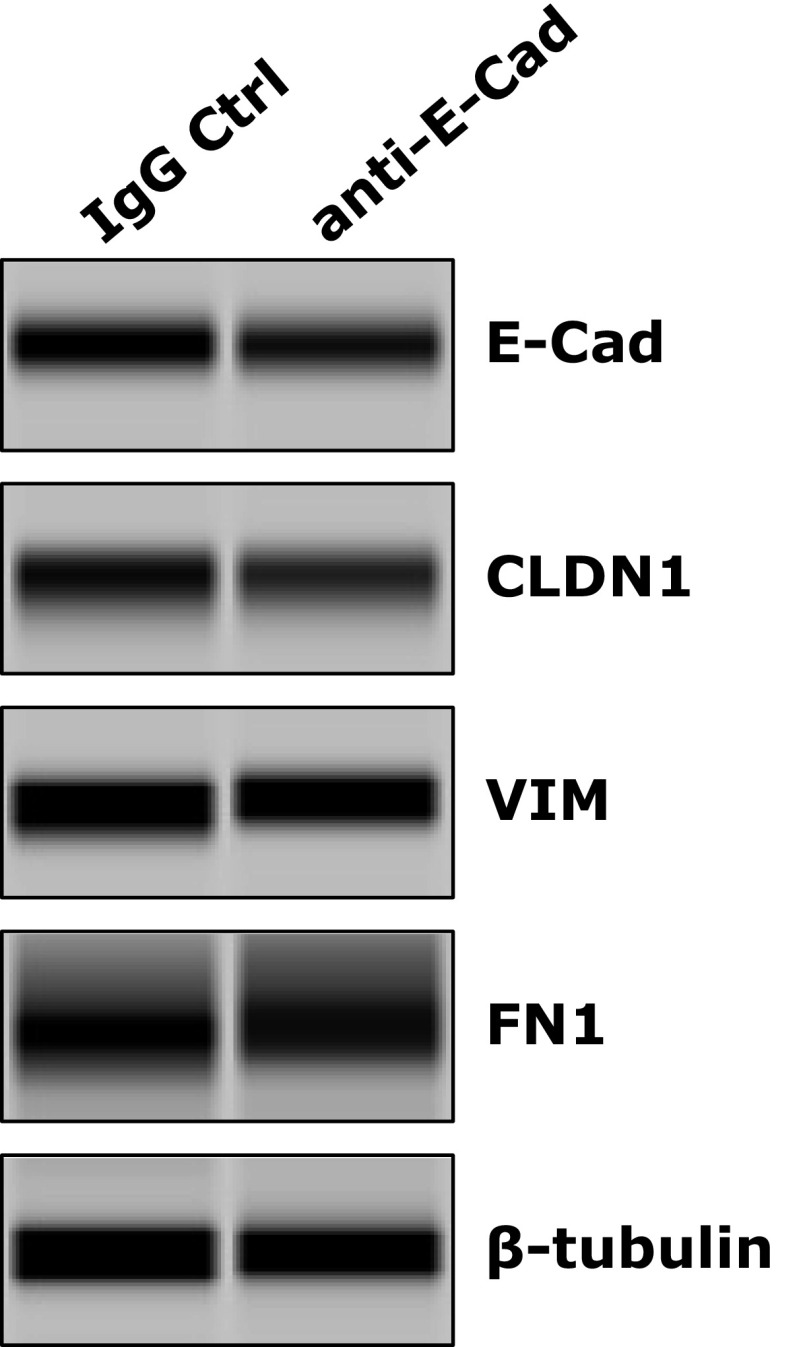

Fig. S7.

Anti–E-cadherin (E-Cad) mAb treatment does not induce EMT in Huh7.5.1 cells. Cells were incubated with anti–E-cadherin or IgG control (Ctrl) mAb at the concentration of 100 μg/mL for 24 h and then harvested for Western blot to determine the protein expression levels of CLDN1 and EMT markers VIM and FN1. Various rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used for detection of gene expression. β-Tubulin served as a loading control for Western blot.

Discussion

HCV infects hepatocytes through a highly orchestrated cascade of cellular events that engage multiple cellular cofactors: the viral entry factors. Our recent effort in pursuing novel HCV host dependencies by using functional genomics and systems biology approaches identified E-cadherin as a previously unappreciated host factor for HCV. Subsequent confirmatory assays demonstrated that E-cadherin is specifically required for the entry of HCV and targets a postbinding step of the viral entry process. The dependence of HCV infection on E-cadherin expression was observed in multiple hepatic cell lines, including Huh7.5.1, HepG2, and PHHs, cells either lacking or presenting polarity. Therefore, it is unlikely that changes in polarity would influence the mode of action of E-cadherin. Mechanistic studies suggested that E-cadherin expression regulates the cell-surface distribution of two main tight junction proteins and HCV coreceptors, CLDN1 and OCLN. In addition, HCV infection is able to down-regulate the expression of E-cadherin and induce EMT. This study represents an important step forward in understanding the molecular mechanisms and cellular regulatory events in the process of HCV entry.

E-cadherin, a type I cadherin and a calcium-dependent cell–cell adhesion glycoprotein expressed in the epithelium, constitutes the core component of adherens junctions that are localized at the basolateral surfaces of polarized epithelia to establish cell polarity, enhance intercellular adhesion, and consequently confer and maintain tissue integrity (26). E-cadherin is composed of an extracellular domain that mediates pathogen adhesion to host cells, a transmembrane domain, and a highly conserved cytoplasmic domain that interacts with catenin to form cadherin–catenin complexes that engage actin, microtubules, and endocytic machinery for pathogen internalization (27). Loss of E-cadherin function or its aberrant expression has been shown to disrupt cell adhesion, resulting in enhanced cellular motility and EMT, thus contributing to the metastatic potential of cancerous cells (27). A large number of pathogens, from viruses (herpes simplex viruses) to bacteria (Listeria monocytogenes), have developed numerous strategies to specifically target cell adhesion molecules for binding and invading host cells or disrupting epithelial integrity for dissemination (28).

We show here that E-cadherin is crucial for HCV entry, although the mechanism is unrelated to virus binding. Silencing of E-cadherin in hepatocytes disrupts the cell surface distribution of CLDN1 and OCLN, two constituent elements of the tight junctions that are essential for HCV entry (12, 13), without affecting the distribution of another tight junction protein, ZO-1. Cellular defenses can target invading viruses in the tight junction region. In hepatocytes, the tight junction protein IFITM1 interacts with CD81 and OCLN and impedes HCV entry (29). Pathogens, like HCV, preferentially take advantage of tight junctions to invade host cells and spread (12). Here we show that localization of CLDN1 and OCLN to the cell surface is dependent on E-cadherin expression. Interestingly, in E-cadherin–KO mice, tight junctions in the neonatal uterus were disrupted, leading to the loss of epithelial cell–cell interaction (30). We therefore propose that E-cadherin exerts a regulatory role in CLDN1 and OCLN localization, as well as tight junction integrity, in hepatocytes to modulate HCV entry.

HCV-infected cells have been shown to exhibit loss of E-cadherin and induction of EMT (31–33). The mechanisms behind these HCV-triggered effects are not fully known. It has been shown that HCV core up-regulates DNMT1 and 3b expression and thus induces hypermethylation of the E-cadherin gene, leading to its repression (34, 35). Many other transcription factors such as Snail1, Slug, ZEB1, and Twist may also suppress E-cadherin directly or indirectly (36). It is worth exploring whether HCV exploits these EMT-related transcription factors to down-regulate E-cadherin expression and induce EMT in hepatocytes. In light of the inhibitory effect of E-cadherin depletion on HCV entry, the induction of EMT by HCV may be a mechanism used by the virus to limit the deleterious effect of superinfection of already infected cells (37, 38).

Chronic HCV infection is an important risk factor for the development of HCC (39). However, the mechanisms underlying HCV-induced hepatocarcinogenesis have yet to be defined. Loss or aberrant expression of E-cadherin has been implicated in a number of human malignancies, including HCC (40). Evidence has also suggested that EMT is an important mechanism for HCC metastasis (41). HCV may use distinct mechanisms for induction of EMT and subsequent hepatic carcinogenesis. The identification of cellular or viral factors that initiate, modulate, or sustain EMT signatures in HCV-triggered liver malignancies may provide valuable targets and strategies to prevent or treat HCV-associated HCC.

Materials and Methods

HCV life-cycle assays were conducted applying various viral pseudoparticles (for entry), subgenomic replicons (for IRES-mediated translation and RNA replication), HCVsc (for single-cycle infection), and HCVcc (for multiple stages) in Huh7.5.1 cells. siRNA treatment (at 50 nM final concentration) was typically allowed for 72 h to achieve maximum knockdown. Blocking antibodies at various concentrations were applied for 2 h before infection with HCVpp or HCVcc, and were present continuously during the infection. Additional information regarding study materials and methods is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Discussion

We found that an anti–E-cadherin mAb efficiently blocked HCV entry in Huh7.5.1 cells. In contrast to E-cadherin silencing by siRNA treatment, the blocking antibody does not diminish the cell membrane localization of CLDN1 and OCLN or disrupt tight-junction integrity. The blocking antibody probably affects the subsequent function of the complex between E-cadherin, CLDN1, and OCLN in HCV entry. Various mAbs targeting the HCV receptor complex have been identified that prevent HCV infection in vitro and in vivo. CLDN1-targeting mAb clears persistent HCV infection in a humanized mouse model without inducing detectable toxicity (42). Anti-CD81 mAbs can block serum-derived or cultured HCV infection in PHHs and other liver cell lines (43, 44). Prophylactic treatment of human liver-urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)-SCID mice with anti-CD81 mAbs completely protected the animals from infection with HCV of various genotypes (45). In addition, antibodies against SR-BI have been shown to prevent HCV infection in human hepatocytes (46). These blocking antibodies are very useful to further unravel the mechanistic roles of these host dependencies in the HCV entry process. Furthermore, the mAbs may be of interest for the development of novel antivirals for prevention and treatment of HCV infection. Indeed, the activity of E-cadherin mAb in restricting HCV entry suggests that E-cadherin may represent an attractive preventive and therapeutic target for HCV entry inhibitors. Further in vivo studies are needed to address the efficacy and safety of E-cadherin inhibition in chronic HCV infection.

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

Human hepatoma cell line Huh7.5.1 (47), provided by Frank Chisari, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, was cultured in complete growth medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Gibco). HepG2-derived HepG2/miR-122/CD81 cell line was provided by Matthew Evans, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and was maintained in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) FBS containing 5 μg/mL of Blasticidin (Invitrogen) (18). PHHs were obtained from Steve Strom, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh (NIH funded Liver Tissue Procurement and Cell Distribution System), and were maintained in Williams E medium containing cell maintenance supplement reagents (Invitrogen).

Viral Propagation, Titration, and Infection.

HCV JFH-1 strain (genotype 2a) was propagated, and viral infectivity was titrated as previously described (47–49). HCV cDNA clones of multiple genotypes and subtypes, provided by Jens Bukh, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, were JFH-1–based recombinants containing the structural proteins (core, E1, and E2), p7, and NS2 of genotypes 1a (H77C), 1b (HC-J4), 2b (HC-J8), 3a (S52), 4a (ED43), 5a (SA13), 6a (HK6a), and 7a (QC69), respectively. Various viral stocks were prepared and titrated as described previously (50). HCV infection was performed at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5, and assays were typically conducted at 48 h postinfection unless otherwise indicated.

Antibodies and Reagents.

Anti-HCV core monoclonal antibody was produced from the α-core 6G7 hybridoma cells provided by Harry Greenberg and Xiaosong He, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Anti-NS5A monoclonal antibody (9E10) was a gift of Charles Rice, The Rockefeller University, New York. The following antibodies were obtained commercially: E-cadherin (24E10) rabbit monoclonal antibody (no. 3195; Cell Signaling Technology), E-cadherin (32A8) mouse monoclonal antibody (no. 5296; Cell Signaling Technology), CLDN1 (XX7) monoclonal antibody (sc-81796; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CLDN1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab15098; Abcam), OCLN (369.7) monoclonal antibody (sc-81812; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ZO-1 mouse monoclonal antibody (ZO1-1A12; Invitrogen), mouse monoclonal SR-BI antibody (25/CLA-1; BD Transduction Laboratories), CD81 (5A6) monoclonal antibody (sc-23962; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Purified mouse anti-human CD81 (no. 555675; BD Pharmingen), anti-VIM rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab45939; Abcam), anti-FN1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab2413; Abcam), N-cadherin (D4R1H) XP Rabbit mAb (no. 13116; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse (G3A1) monoclonal antibody IgG1 isotype control (no. 5415; Cell Signaling Technology), monoclonal α-β-tubulin (TUB 2.1; Sigma), Alexa Fluor 488 goat α-mouse IgG (A11001; Life Technologies), Alexa Fluor 488 goat α-rabbit IgG (A11008; Life Technologies), Alexa Fluor 568 goat α-mouse IgG (A11004; Life Technologies), Alexa Fluor 568 goat α-rabbit IgG (A11011; Life Technologies), Alexa Fluor 568 goat α-rat IgG (A11077; Life Technologies), and Alexa Fluor 647 goat α-mouse IgG (A21235; Life Technologies). Recombinant human TGF-β1 and TGF-β inhibitor SB 431542 were purchased from R&D Systems.

siRNA Transfection.

ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool or individual siRNAs (Dharmacon) were transfected into Huh7.5.1 or HepG2/miR-122/CD81 cells at a 50-nM final concentration by using a reverse-transfection protocol applying Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) as previously described (17). For PHHs, cells were seeded onto 12-well plates at 500,000 cells per well and transfected with siRNA reagents at a final concentration of 50 nM using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). Unless otherwise indicated, further treatments or assays were typically performed 72 h after siRNA transfection, when gene silencing reaches the highest efficiency.

Viral Entry Assay.

HCVpps, VSV-Gpps, and MLVpps were generated as previously described (8, 51). Huh7.5.1 or HepG2/miR-122/CD81 cells were transfected with various siRNAs by using a reverse-transfection protocol and seeded at the density of 4,500 cells per well in 96-well white microplates (Greiner Bio-one). After 72 h of siRNA treatment, cells were infected with HCVpps of various genotypes, VSV-Gpps, or MLVpps. At 48 h postinfection, cells were lysed in 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and subsequently measured for firefly luciferase (Promega) activity by using a POLARstar Omega multidetection microplate reader (BMG Labtech).

HCV Single-Cycle Infection Assay.

HCVsc was generated from a replicon transpackaging system as previously described (8, 20, 21). The core assembly-defective HCVsc can efficiently enter and replicate viral RNA in cells but is unable to produce progeny virus, thereby allowing separation of the early stages of the HCV life cycle (entry through genome replication) and late stages (virion assembly and secretion) as two distinct steps (8, 20, 21). In the assay, Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with various siRNAs for 72 h before infection with HCVsc. At 48 h postinfection, cells were harvested and measured for firefly luciferase activity.

HCV Subgenomic Replicon Assay.

Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with various siRNAs for 72 h and then transfected with JFH1-RLuc subgenomic replicon RNA. Cell lysates were collected at 48 h posttransfection and measured for Renilla luciferase activity by using the Renilla Luciferase Assay System (Promega).

HCV IRES-Mediated Translation Assay.

Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with various siRNAs and incubated for 72 h, and then transiently transfected with pHCV-CLX-CMV RNA that harbors a firefly luciferase reporter gene. After 24 h, cell lysates were collected and measured for firefly luciferase activity by using the Firefly Luciferase Assay System (Promega).

HCV Attachment Assay.

Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with various siRNAs for 72 h and subsequently incubated with JFH1 HCVcc at 4 °C for 2 h. Cells were then extensively washed with cold PBS solution to remove the unbound virus. Virus binding to cells was determined by measuring intracellular HCV RNA levels by quantitative PCR.

Transferrin Endocytosis Assay.

Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with various siRNAs. After 72 h, cells were incubated with Transferrin from Human Serum, Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate (Life Technologies) at 37 °C. Two hours later, cells were fixed, and transferrin internalization (in green) was observed under the confocal microscope. siRNA targeting RAB5, a host-dependency factor for the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of HCV (52), was applied as a positive control.

LDL-Uptake Assay.

Huh7.5.1 cells were treated with nontargeting control, LDL receptor, CLDN1, or E-cadherin siRNA for 72 h, and subsequently incubated with 12.5 μg/mL of LDL from Human Plasma, BODIPY Conjugate (Life Technologies) at 37 °C for 12 h. Cells were then fixed with 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), and the nuclei were stained by Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Immunofluorescence images were acquired by using ZEN 2010 software under a Zeiss confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

HCV RNA Isolation and Quantification.

Intracellular RNA was extracted from whole-cell lysates by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Viral RNA from supernatants (extracellular HCV RNA) was isolated by using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Copy numbers of intracellular and extracellular HCV RNA were determined by Q-PCR with previously described probe, primers, and parameters (17). The relative amount of HCV RNA was normalized to the housekeeping control gene human 18S rRNA (Applied Biosystems).

In Vitro Transcription of HCV RNA and Transfection.

HCV full-length or subgenomic RNAs were linearized with Xba I and purified by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction. In vitro transcription was performed by using the MEGAscript T7 kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and quantity of RNA were evaluated by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). RNA transfection was performed by using DMRIE-C Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene-Expression Assay.

Total cellular RNA was extracted by using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). The mRNA levels of target genes were quantified by Q-PCR using gene-specific primers and probes (IDT) and TaqMan Gene Express Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA levels were calculated with the ΔΔCT method, using 18S rRNA as the internal control for normalization.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy.

Huh7.5.1 or HepG2/miR-122/CD81 cells grown on Lab-Tek II borosilicate four-well chamber coverslips (Nunc) were fixed with 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated with blocking solution in PBS solution containing 3% (wt/vol) BSA fraction V (BSA; MP Biomedicals) and 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Cells were then labeled with appropriate primary antibodies diluted in PBS solution with 1% BSA, and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 488, 568, or 647 secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) in PBS solution with 1% BSA. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) at 1:5,000 in PBS solution. Each step was followed by three washes with PBS solution. Confocal laser scanning microscopic analysis was performed with an Axio Observer.Z1 microscope equipped with a Zeiss LSM 5 Live DuoScan System under an oil-immersion 1.4 N.A. 63× objective lens (Carl Zeiss). Images were acquired by using ZEN 2010 software (Carl Zeiss). Dual- or triple-color images were acquired by consecutive scanning with only one laser line active per scan to avoid cross-excitation.

Western Blot.

Whole-cell lysates were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and proteins were then separated in a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies) in NuPAGE Mes or Mops SDS running buffer (Life Technologies). Gels were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Life Technologies) in NuPAGE transfer buffer (Life Technologies). Membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with appropriate primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer [2% blocking agent (GE Healthcare) in 0.05% TBS-Tween] and subsequently washed five times for 5 min with 0.05% TBS-Tween. Membranes were then incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibody (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. After five washing steps with 0.05% TBS-Tween and an additional washing step in TBS, immunoreactive proteins were detected by using ECL Advance reagent (GE Healthcare). For Fig. 4 C and D and Figs. S3C, S6 A, B, and D, and S7, cells were harvested by using RIPA Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) with cOmplete protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). Western blots were performed by using Wes Split Buffer Master Kit (ProteinSimple) on the “Wes” automated Western blot instrument (ProteinSimple) per the manufacturer's instructions.

Blocking Antibody Treatment.

Huh7.5.1 cells were seeded onto 96-well white plates and then preincubated with increasing concentrations of anti–E-cadherin, anti-CD81, or isotype IgG control monoclonal antibodies for 2 h at 37 °C before infection with HCVpps or HCV P7-Luc. After 48 h, viral infection was determined by measuring the luciferase activities.

ATPlite Assay.

In 96-well white assay plates (Greiner Bio-One), Huh7.5.1 cells (10,000 cells per well) were transfected with various siRNAs at a final concentration of 50 nM each. After 72 h of siRNA treatment, cells were harvested and lysed with 50 mL of mammalian cell lysis solution (PerkinElmer). Five minutes later, 50 mL of ATPlite substrate solution (PerkinElmer) was applied, and the luminescence ATPlite activity in each well was measured by using a POLARstar Omega multidetection microplate reader.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SD. The two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. The level of significance is denoted in each figure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ching-Sheng Hsu and Véronique Pène for technical assistance; Francis Chisari, Charles Rice, Takaji Wakita, François-Loïc Cosset, Michael Niepmann, Jens Bukh, Tetsuro Suzuki, and Takanobu Kato for their generosity in providing reagents; and all members of the Liver Diseases Branch for discussion and support. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 7298.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1602701113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333–1342. doi: 10.1002/hep.26141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen HR. Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2429–2438. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verna EC, Brown RS., Jr Hepatitis C virus and liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10(4):919–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1907–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1213651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisari FV. Unscrambling hepatitis C virus-host interactions. Nature. 2005;436(7053):930–932. doi: 10.1038/nature04076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartenschlager R, Cosset FL, Lohmann V. Hepatitis C virus replication cycle. J Hepatol. 2010;53(3):583–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheel TK, Rice CM. Understanding the hepatitis C virus life cycle paves the way for highly effective therapies. Nat Med. 2013;19(7):837–849. doi: 10.1038/nm.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, et al. Integrative functional genomics of hepatitis C virus infection identifies host dependencies in complete viral replication cycle. PLoSPathog. 2014;10(5):e1004163. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Virology and cell biology of the hepatitis C virus life cycle: An update. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1) suppl:S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pileri P, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282(5390):938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarselli E, et al. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 2002;21(19):5017–5025. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans MJ, et al. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature. 2007;446(7137):801–805. doi: 10.1038/nature05654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ploss A, et al. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature. 2009;457(7231):882–886. doi: 10.1038/nature07684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lupberger J, et al. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17(5):589–595. doi: 10.1038/nm.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sainz B, Jr, et al. Identification of the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor as a new hepatitis C virus entry factor. Nat Med. 2012;18(2):281–285. doi: 10.1038/nm.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin DN, Uprichard SL. Identification of transferrin receptor 1 as a hepatitis C virus entry factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(26):10777–10782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301764110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, et al. A genome-wide genetic screen for host factors required for hepatitis C virus propagation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(38):16410–16415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narbus CM, et al. HepG2 cells expressing microRNA miR-122 support the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle. J Virol. 2011;85(22):12087–12092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05843-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Q, Jiang J, Luo G. Syndecan-1 serves as the major receptor for attachment of hepatitis C virus to the surfaces of hepatocytes. J Virol. 2013;87(12):6866–6875. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03475-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinmann E, Brohm C, Kallis S, Bartenschlager R, Pietschmann T. Efficient trans-encapsidation of hepatitis C virus RNAs into infectious virus-like particles. J Virol. 2008;82(14):7034–7046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00118-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masaki T, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus by using RNA polymerase I-mediated transcription. J Virol. 2010;84(11):5824–5835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02397-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ploss A, Evans MJ. Hepatitis C virus host cell entry. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(3):178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson GK, et al. A dual role for hypoxia inducible factor-1α in the hepatitis C virus lifecycle and hepatoma migration. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):803–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin W, et al. Hepatitis C virus regulates transforming growth factor beta1 production through the generation of reactive oxygen species in a nuclear factor kappaB-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2509–2518. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris TJ, Tepass U. Adherens junctions: From molecules to morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(7):502–514. doi: 10.1038/nrm2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryant DM, Stow JL. The ins and outs of E-cadherin trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14(8):427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonazzi M, Cossart P. Impenetrable barriers or entry portals? The role of cell-cell adhesion during infection. J Cell Biol. 2011;195(3):349–358. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkins C, et al. IFITM1 is a tight junction protein that inhibits hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology. 2013;57(2):461–469. doi: 10.1002/hep.26066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reardon SN, et al. CDH1 is essential for endometrial differentiation, gland development, and adult function in the mouse uterus. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(5):141,1-110. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.098871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akkari L, et al. Hepatitis C viral protein NS5A induces EMT and participates in oncogenic transformation of primary hepatocyte precursors. J Hepatol. 2012;57(5):1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bose SK, Meyer K, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB, Ray R. Hepatitis C virus induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in primary human hepatocytes. J Virol. 2012;86(24):13621–13628. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02016-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park J, Jang KL. Hepatitis C virus represses E-cadherin expression via DNA methylation to induce epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446(2):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ripoli M, et al. Hypermethylated levels of E-cadherin promoter in Huh-7 cells expressing the HCV core protein. Virus Res. 2011;160(1-2):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arora P, Kim EO, Jung JK, Jang KL. Hepatitis C virus core protein downregulates E-cadherin expression via activation of DNA methyltransferase 1 and 3b. Cancer Lett. 2008;261(2):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: An alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(6):415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaller T, et al. Analysis of hepatitis C virus superinfection exclusion by using novel fluorochrome gene-tagged viral genomes. J Virol. 2007;81(9):4591–4603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02144-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tscherne DM, et al. Superinfection exclusion in cells infected with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2007;81(8):3693–3703. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01748-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shlomai A, de Jong YP, Rice CM. Virus associated malignancies: The role of viral hepatitis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;26:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang B, Guo M, Herman JG, Clark DP. Aberrant promoter methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(3):1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63469-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mailly L, et al. Clearance of persistent hepatitis C virus infection in humanized mice using a claudin-1-targeting monoclonal antibody. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):549–554. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molina S, et al. Serum-derived hepatitis C virus infection of primary human hepatocytes is tetraspanin CD81 dependent. J Virol. 2008;82(1):569–574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01443-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fofana I, et al. A novel monoclonal anti-CD81 antibody produced by genetic immunization efficiently inhibits Hepatitis C virus cell-cell transmission. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meuleman P, et al. Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology. 2008;48(6):1761–1768. doi: 10.1002/hep.22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catanese MT, et al. High-avidity monoclonal antibodies against the human scavenger class B type I receptor efficiently block hepatitis C virus infection in the presence of high-density lipoprotein. J Virol. 2007;81(15):8063–8071. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00193-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong J, et al. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(26):9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wakita T, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med. 2005;11(7):791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindenbach BD, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309(5734):623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gottwein JM, et al. Development and characterization of hepatitis C virus genotype 1-7 cell culture systems: Role of CD81 and scavenger receptor class B type I and effect of antiviral drugs. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):364–377. doi: 10.1002/hep.22673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lavillette D, et al. Characterization of host-range and cell entry properties of the major genotypes and subtypes of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2005;41(2):265–274. doi: 10.1002/hep.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coller KE, et al. RNA interference and single particle tracking analysis of hepatitis C virus endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(12):e1000702. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]