Abstract

Detailed structural analyses of the mushroom body which plays critical roles in olfactory learning and memory revealed that it is directly connected with multiple primary sensory centers in Drosophila. Connectivity patterns between the mushroom body and primary sensory centers suggest that each mushroom body lobe processes information on different combinations of multiple sensory modalities. This finding provides a novel focus of research by Drosophila genetics for perception of the external world by integrating multisensory signals.

The mushroom body (MB) is one of the prominent neuropils in the insect brain. Genetic manipulations of the MB intrinsic neurons called Kenyon cells in Drosophila have proved that the MB is an important site for olfactory learning and memory1,2,3. In contrast, the contribution of the Drosophila MB to general learning and memory is under debate. For example, flies in which postembryonic Kenyon cells were ablated by hydroxyurea showed normal visual, spatial, tactile, and motor learning, but were defective in olfactory learning4. Instead of the MB, the central complex is suggested to be the site of the memory trace of visual patterns5,6. Conversely, recent works based on the observation of flies in which neural transmission of Kenyon cells were blocked have shown that the MB is required for visual and gustatory learning7,8,9. To resolve these discrepancies, which probably reflect the different fly backgrounds and behavioral paradigms tested, accumulation of anatomical knowledge is indispensable. In Drosophila, it has been reported that only the olfactory antennal lobe (AL)10,11 and visual optic lobe (OL)8 are directly connected with the MB calyx where Kenyon cells receive sensory inputs. On the other hand, the MB calyx in other insects such as the honeybee is connected with not only the OL and AL, but also the gustatory subesophageal zone (SEZ)12,13. We thus analyzed the connectivity patterns between the primary sensory centers and MB calyx by dye injections and genetic labeling methods in Drosophila.

Results

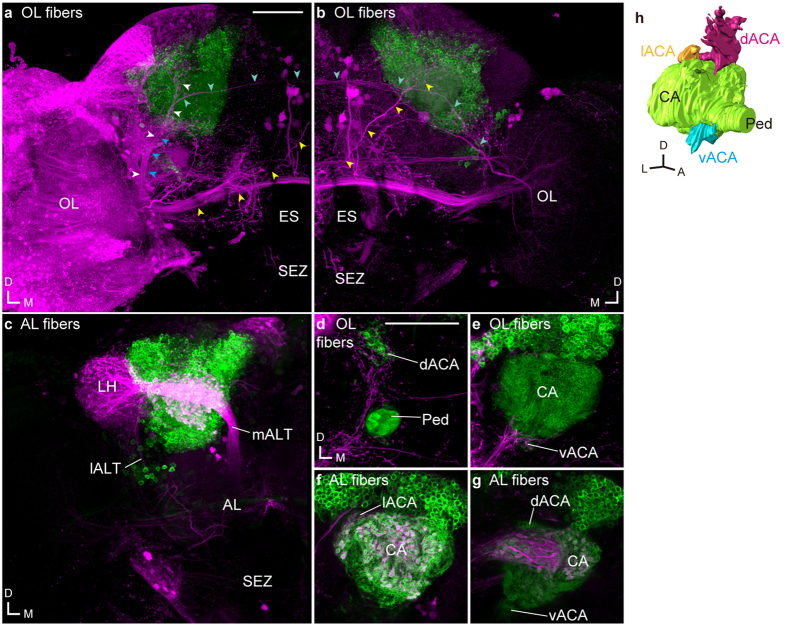

We performed injections of dextran conjugated with fluorescent dye into the primary sensory centers to investigate whether the MB calyx in Drosophila is also connected with multiple primary sensory centers. The MB calyx can be divided into four parts: the main calyx (CA), dorsal, lateral, and ventral accessory calyces (d-, l-, and vACA)8,14,15,16,17,18,19 (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Movie S1). The dye injections revealed that the MB calyx is connected with not only the AL and OL, but also SEZ via three major antennal lobe tracts (ALTs), three OL-calycal tracts (OLCTs), and one subesophageal-calycal tract (SCT) (Fig. 1a–g). The neurons running through the OLCTs are also called visual projection neuron (VPN)-MBs8. The terminals of ALTs were observed not only in the CA10,11, but also in the dACA and lACA. The OLCTs terminated in both dACA and vACA, whereas the SCT in dACA.

Figure 1. Sensory pathways visualized by dextran injection into the primary sensory center in Drosophila.

Dextran conjugated with tetramethylrhodamine and biotin (magenta) was injected into the optic lobe (OL, (a,b)) or antennal lobe (AL, (c)) in flies expressing GFP (green) in Kenyon cells with OK107-GAL4. White, blue, and yellow arrowheads indicate the OLCT1, OLCT2, and OLCT5, respectively. Some OLCT2 neurons also innervate the contralateral hemisphere (cyan arrowheads). (d–g) The accessory calyces innervated by the labeled cells from the OL (d,e) and AL (f,g). (h) The oblique view of the mushroom body calyx labeled with OK107-GAL4. Green, magenta, yellow, and cyan represent the main calyx and pedunculus, dorsal, lateral, and ventral accessory calyx, respectively. The position of the lateral ACA was determined with the anti-SYNAPSIN signals. Scale bars = 50 μm. A, anterior; AL, antennal lobe; CA, main calyx; D, dorsal; dACA, dorsal accessory calyx; ES, esophagus; L, lateral; lACA, lateral accessory calyx; lALT, lateral antennal lobe tract; LH, lateral horn; M, medial; mALT, medial antennal lobe tract; OL, optic lobe; Ped, pedunculus; SEZ, subesophageal zone; vACA, ventral accessory calyx.

We then screened for the Janelia Farm GAL4 strains14 which visualize neurons running through these tracts and innervating the MB calyx except for the conventional ALT neurons which are known to supply branches into the main calyx10,11,20, subsequently identifying eleven strains, which labeled five OLCTs, two ALTs, and one SCT which send projections into the ACAs of the MB (Table 1). The dACA is innervated by two OLCTs, the medial ALT (mALT), and SCT. The lACA is innervated by one OLCT and the mediolateral ALT (mlALT) and the vACA by four OLCTs, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Dye injection and labeling with the GAL4 lines showed that the terminal areas of OLCT and ALT neurons are overlapping in the lACA and posterior area of the dACA, however, are distributed to the vACA and CA, respectively, in a segregated manner (Fig. 1d–g).

Table 1. Neurons that connect primary sensory centers and the mushroom body accessory calyx revealed by single cell analyses.

| Cell type | Strain number | mushroom body calyx | primary sensory center | projections outside MB calyx | cell body |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLCT1 | 40712 | dACA#, vACA | OL(LO6*) | ICL, PLP, SLP, SCL | near AME |

| OLCT2 | 48048 | vACA | OL(ME7) | PLP | near AME |

| OLCT2 | 38695 | vACA | OL(AME, ME7**) | PLP, SPS | near AME |

| OLCT2 | 38866 | vACA | OL(AME, ME7) | PLP | near AME |

| OLCT2 | 49421 | vACA | OL(AME,ME1-5**, ME6-7***) | PLP, ICL | near AME |

| OLCT3 | 39199 | lACA | OL(AME) | PLP, SLP | SLP |

| OLCT4 | 40712 | vACA | OL(AME, LO6, ME7) | ICL, PLP, WED | near AME |

| OLCT5 | 40596 | dACA, vACA | OL(AME, ME7*) | ATL, ICL, PLP, SCL, SLP, SMP | SPS |

| mALT | 39316 | dACA##, CA | AL(VP1) | LH | GNG |

| mlALT | 48816 | lACA | AL(VP3) | GNG | |

| SCT1 | 49862 | dACA## | GNG | SLP, SMP, LH | posterior to PB |

| SCT1 | 49910 | dACA## | FLA | SLP, SMP, LH | posterior to PB |

Numbers following the ME and LO represent the layer numbers in which the neurons arborize. # and ## show that the neuron arborizes only in the anterior (#) and posterior (##) part of the dACA, respectively. Asterisks represent that the neurons which innervate only in the dorsal three-quarters (*), ventralmost (**), or ventral half (***) of the lobula or medulla were observed. AL, antennal lobe; AME, accessory medulla; ATL, antler; CA, main calyx; AVLP, anterior ventrolateral protocerebrum; dACA, dorsal accessory calyx; FLA, flange; GNG, gnathal ganglia; ICL, inferior clamp; lACA, lateral accessory calyx; LH, lateral horn; LO, lobula; mALT, medial antennal lobe tract; ME, medulla; mlALT, mediolateral antennal lobe tract; OL, optic lobe; OLCT, optic lobe calycal tract; PB, protocerebral bridge; PLP, posterior lateral protocerebrum; PRW, prow; SCL, superior clamp; SCT, subesophageal calycal tract; SLP, superior lateral protocerebrum; SMP, superior medial protocerebrum; SPS, superior posterior slope; vACA, ventral accessory calyx; WED, wedge.

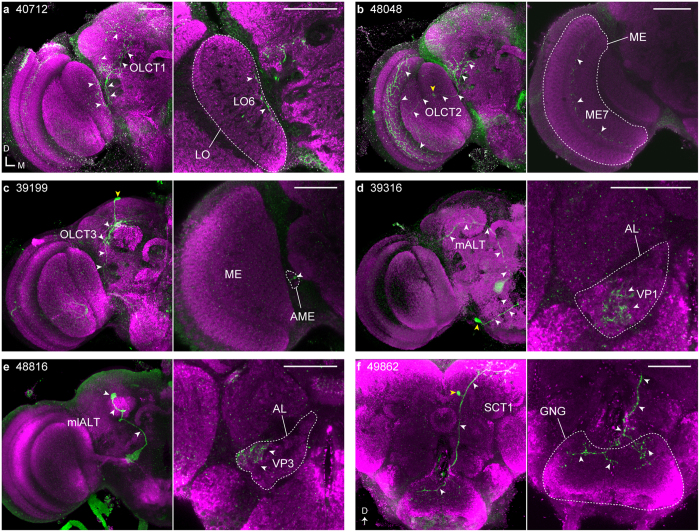

We further visualized the morphologies of single cells of these tracts by performing the FLP-out experiments21 using the GAL4 strains (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S2, and Table 1). Most of the OLCTs emanated from the seventh layer of the medulla (ME7, serpentine layer), sixth layer of the lobula (LO6), or accessory medulla (AME). The ME7 and LO6 are the target layers of the chromatic Tm neurons22,23, suggesting that these layers are related to color processing. Only a few neurons innervate the layer entirely, however, most OLCT neurons have specific arborization areas in the OL. For example, one OLCT1 neuron innervates the dorsal three-quarters of the LO6 (Fig. 2a), whereas the innervation of one OLCT2 neuron is restricted to the ventralmost ME7 (Table 1). This result suggests that these neurons transfer information of specific visual fields. It should be noted that none of the OLCT neurons have the same morphologies with recently reported VPNs (VPN-MB1 and VPN-MB2) terminating in the vACA8. For the ALTs, we found two ALT neurons terminating in the ACA. One neuron, which innervates the VP1 glomerulus that receives chemosensory, hygrosensory, or thermosensory inputs from the sensory neurons in the sacculus of the antenna19,24, projects into the dACA through the mALT (Fig. 2d). The other, mlALT neuron, originating from the VP3 glomerulus which receives input from cold-sensing neurons19,25, runs through the mediolateral ALT and then pedunculus, and forms a cloud of terminals in the lACA, the structure of which is quite similar with the terminals of the tritocerebral tract in the orthopteran insects26 (Fig. 2e). The morphology of this mlALT neuron appears quite similar with that of the t5ALT neuron14,19, though the neuron we found runs through the mlALT. The SCT neuron originating from the gnathal ganglia (GNG) or flange (FLA) joins the mALT and sends branches into the dACA (Fig. 2f).

Figure 2. Single cell morphologies of the neurons which connect between the primary sensory centers and MB accessory calyx revealed by FLP-out experiments.

Strain number of the Janelia Farm GAL4 line is shown top left in the left panel. Magenta shows the anti-SYNAPSIN antibody signals. Left panel: Single neuron (green) labeled with the GAL4 strain by the FLP-out experiment. The cell body and trajectory of the neural fiber from the primary sensory center to the calyx are indicated by yellow and white arrowheads, respectively. Right panel: Arborizations in the primary sensory center shown by arrowheads. (a,b,d and e) are single confocal images. AME, accessory medulla; GNG, gnathal ganglia; LO, lobula; ME, medulla; mlALT, mediolateral antennal lobe tract; OLCT, optic lobe calycal tract; SCT, subesophageal calycal tract. Genotype: Hs-flp;UAS > CD2, y+ >CD8::GFP;GAL4. Scale bars = 50 μm.

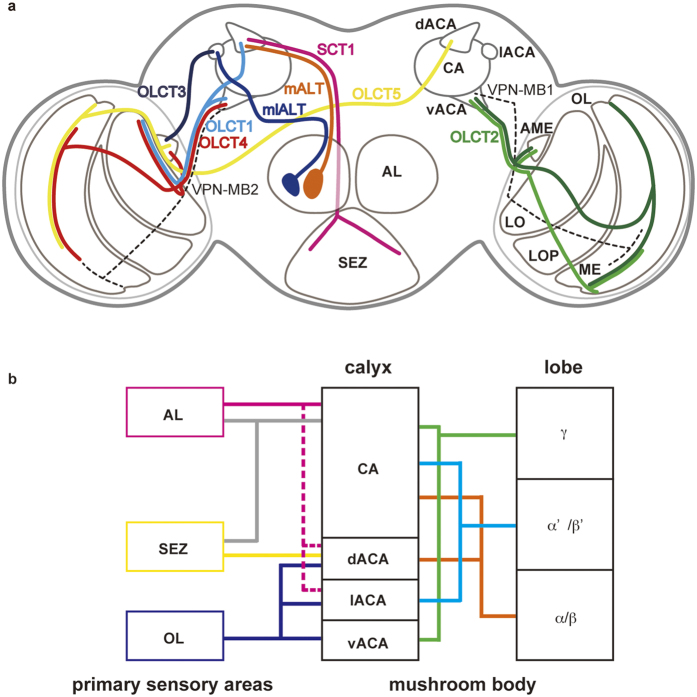

Taken together, the dACA is connected with the LO6, ME7, AME, VP1 glomerulus, FLA, and GNG. On the other hand, the vACA is linked with the LO6, ME1-7, and AME, whereas the lACA is linked with the AME and VP3 glomerulus. This indicates that each calycal part receives sensory inputs of different combinations of modalities and that the MB in Drosophila may play a role in general learning and memory.

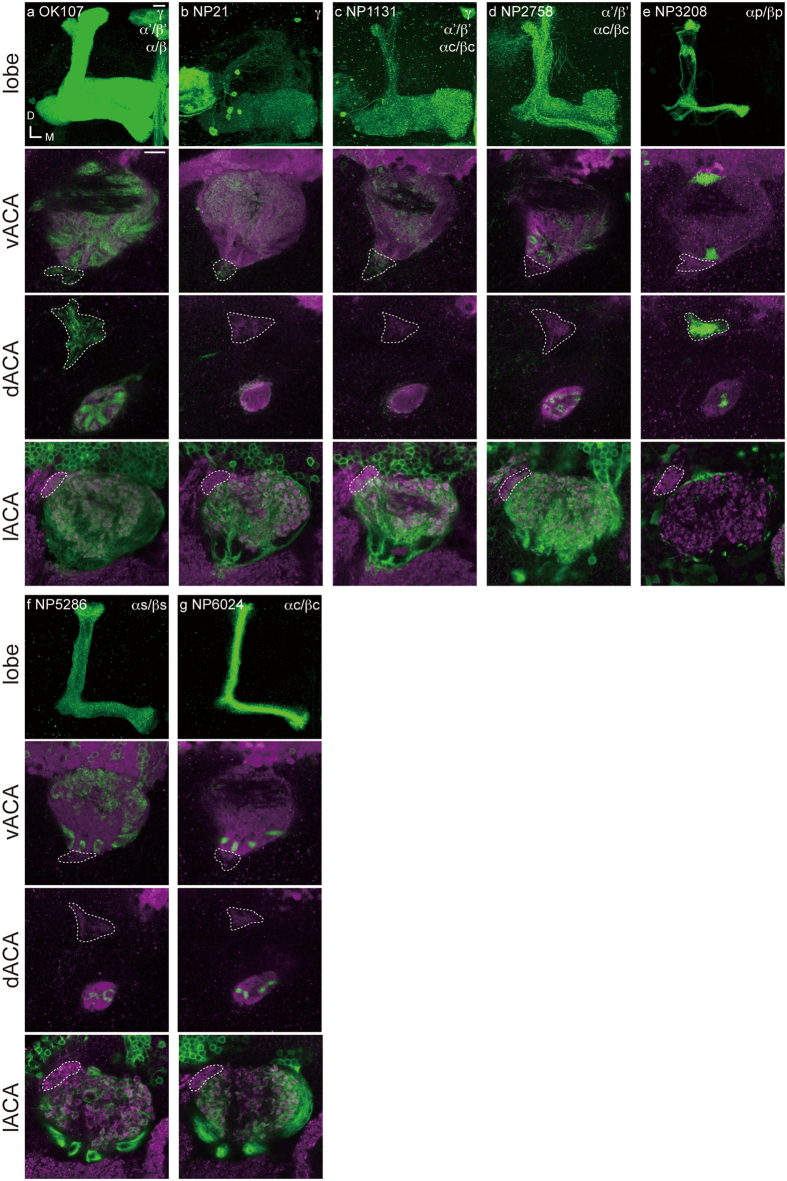

We furthermore investigated how each calycal part is governed by different classes of Kenyon cells. Kenyon cells are classified according to the lobes they terminate in: γ, α/β, or α’/β’ lobe neurons15,16,17,27,28. We analyzed the dendritic patterns of these neurons by using the GAL4 enhancer-trap strains we previously reported28. Since there were no available strains for labeling α’/β’ lobe neurons specifically, we compared staining patterns among the strains labeling Kenyon cells of multiple lobes to estimate the probable innervation areas of α’/β’ lobe neurons. Each population of γ, α/β, or α’/β’ lobe neurons arborizes in the CA, whereas the ACAs are innervated by specific populations (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The dACA is innervated by a subpopulation of α/β lobe (αp/βp) Kenyon cells28, whereas the vACA is innervated by γ lobe neurons8,15,16,17. However, the innervation into the lACA was not observed in those strains that specifically label γ or α/β lobe neurons, but strains which visualize α’/β’ lobe neurons, suggesting that the lACA is innervated by α’/β’ lobe neurons. Since each ACA is connected with different primary sensory centers, these anatomical findings suggest that each lobe may have different functions in multimodal sensory processing (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. The connectivity patterns between the mushroom body accessory calyces and lobes by Kenyon cells.

Top: The mushroom body lobes (green) labeled with the GAL4 enhancer-trap strain. Strain number and labeled Kenyon cell subpopulations are shown top left and top right, respectively. Bottom three panels: The mushroom body calyces innervated by Kenyon cell subpopulation shown in green. Magenta signals represent the entire calyx visualized with MB247-DsRed (vACA and dACA panels) and anti-SYNAPSIN antibody signals (lACA panels). The lACA is identified with the strong anti-SYNAPSIN antibody signals. The vACA (top), dACA (middle), and lACA (bottom) are indicated by dashed lines. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Table 2. GAL4 enhancer-trap strains that label Kenyon cells.

| strain number | γ | α′/β′ | α/β | CA | dACA | lACA | vACA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OK107 | entire | entire | entire | + | + | + | + |

| NP21 | entire | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| NP1131 | entire | entire | core | + | − | + | + |

| NP2758 | − | entire | core | + | − | + | − |

| NP3208 | − | − | posterior | − | + | − | − |

| NP5286 | − | − | surface | + | − | − | − |

| NP6024 | − | − | core | + | − | − | − |

It should be noted that more lobes were labeled with NP1131 and NP2758 than those in our previous work28, possibly because the GFP expression is enhanced by the repeats of UAS in this work.

Figure 4. The connectivity pattern between the primary sensory centers and mushroom body.

(a) Schema of sensory pathways to the MB ACA revealed by single cell analyses. It should be noted that branches outside of the primary sensory centers and MB calyx are not drawn in this schema. To reduce the complexity, the OLCT pathways as shown are divided betweeen the two hemispheres. The VPN-MB1 and VPN-MB2 which innervate the ME8 and ME7 respectively and terminate in the vACA8 are shown in dashed black lines. (b) Diagram of connectivity patterns of calycal parts with primary sensory centers and MB lobes. The antenno-subesophageal tract reported previously11 are shown in gray lines. Magenta dashed lines represent the thermosensory pathways19. LOP, lobula plate.

Discussion

This study reveals multimodal sensory pathways into the MB calyx in Drosophila as has been reported in such insects as the honeybee, ant, butterfly and cockroach12,13,29,30. Recent work has also revealed that two other OLCT neurons, VPN-MB1 and MB2 are required for visual memories of color and brightness in Drosophila8. In the bumblebee and honeybee, the neurons of the anterior inferior optic tract and the lobula tract which arborize in the serpentine layer of the medulla and in LO5 or LO6 respectively and project to the MB calyx respond to color and motion stimuli31. Due to morphological similarities of the OLCT neurons found in this study to these neurons and VPN-MBs8, the Drosophila MB may also receive similar visual information and combine it with odor, gustatory, and temperature information in each lobe. Recent physiological works support this idea: the γ lobe neurons innervating the vACA respond to visual stimuli8, the ALT neuron terminating in the lACA shows calcium responses to temperature shifts19, and taste activity has been observed in the dACA9. Further physiological works revealing the sensory information transferred from the primary sensory centers to the MB calyx by the neurons found in this study need as yet to be determined.

Previous works have shown that each MB lobe contributes to a different temporal phase of memory1,2. This study suggests that each lobe functions in integrating a different combination of multiple sensory modalities. In the cockroach, the MB extrinsic neurons which innervate the MB lobe respond to multimodal sensory inputs in a context-specific manner32. Readily available Drosophila genetics17,18,28 can provide opportunities to reveal novel neural mechanisms by which a rich variety of sensory cues are combined to represent coherent perception of the external world.

Methods

Drosophila strains

To visualize the MB, OK10733, six GAL4 enhancer-trap strains28 (obtained from Kyoto Drosophila Genetic Resource Center), and MB247-DsRed line34 (gifted from Thomas Riemensperger and Andre Fiala) were used. To label the neurons which connect the primary sensory center and the MB calyx, we screened for about 6000 Janelia Farm GAL4 strains14,35 from the expression data of Bloomington Drosophila stock center (BDSC) website (http://flystocks.bio.indiana.edu/Browse/gal4/gal4_Janelia.php) and identified eleven strains. These strains were crossed with a strain carrying UAS-GFP, UAS-mCD8::GFP36 gifted from Aki Ejima, or 20xUAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP37 (#32194, BDSC). To reveal the morphologies of single neurons (see below), the Janelia Farm GAL4 strains were crossed with flies carrying Hs-flp and UAS > CD2, y+ >CD8::GFP21 kindly provided by Gary Struhl. Except for the FLP-out experiments, flies were raised at 25 degrees Celsius with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. We analyzed female flies between 2 and 8 days after eclosion.

Dextran injection into the primary sensory centers

Flies were anesthetized in a vial on ice for less than a minute and were fixed to plastic chambers with wax and epoxy. The compound eye, top of the head, or proboscis was opened with forceps in Drosophila saline (in mM: NaCl 103, KCl 3, MgCl2 4, CaCl2 1.5, NaHCO3 26, TES 5, trehalose 10, glucose 10, sucrose 7, NaH2PO4 1, adjusted to pH 7.25 with HCl). After fat, air sacs, and sheathes around the OL, AL, or SEZ were gently removed with forceps, dextran conjugated with tetramethylrhodamine and biotin (3 kDa, D-3308, Life Technologies) was injected into one of the OL, AL and SEZ with forceps20. Within 20 minutes after dextran injection, the brains were dissected out and fixed with 4% formaldehyde or 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 50 minutes at room temperature. The brains were then washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). When the GFP and tetramethylrhodamine signals needed to be enhanced, the brains were further incubated in the rabbit anti-GFP antibody and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated streptavidin (S-11226, Life Technologies; 1 mg/l diluted in 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS (PBST)), respectively, followed by the antibody staining procedures (see below). The brains were finally mounted in 50 or 80% glycerol/PBS.

Antibody staining

Brains were dissected out in PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 50 minutes. After washing with PBS for 5 minutes three times, the brains were then shaken in the blocking solution: 10% goat serum in PBST for an hour. They were incubated in the blocking solution containing primary antibodies overnight at room temperature with shaking. After washing with PBST, the brains were then incubated in the blocking solution containing secondary antibodies overnight at room temperature with shaking. Finally, the brains were washed with PBS and mounted in 50 or 80% glycerol/PBS.

For primary antibodies, we used rabbit anti-GFP antibody (A11122, Life Technologies; diluted at 1:200 except for the FLP-out experiments, see below), mouse anti-GFP antibody (12A6, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa; diluted at 1:200), or mouse anti-SYNAPSIN antibody38 (3C11, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa; diluted at 1:10). For secondary antibodies, we used goat anti-rabbit/mouse antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 (A11001, A11004, A11034, and A11036, Life Technologies; diluted at 1:200), except for the FLP-out experiments (see below).

Labeling single neurons with GFP

Janelia Farm GAL4 strains labeled multiple neurons including our targets, which prevented us from analyzing the morphology of single cells. To reduce the number of neurons labeled, we used the FLP-out system21. In this system, we crossed each GAL4 strain with the flies carrying Hs-flp and UAS > CD2, y+ >CD8::GFP and incubated one-day old adult offspring at 37 degrees Celcius for 1 hour to express the flippase gene to induce somatic recombination randomly, which resulted in GFP expression in a fewer numbers of neurons. We then maintained the flies for 6–8 days at 25 degrees Celcius before dissecting the brains out. The brains were then fixed with 4% PFA, and immunostained with the rabbit anti-GFP antibody (diluted at 1:1000) and the mouse anti-SYNAPSIN antibody (diluted at 1:20). For secondary antibodies, we used goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa Flour 488 (diluted at 1:1000) and goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with Alexa Flour 568 (diluted at 1:200). The brains were washed with PBS and finally mounted in 80% glycerol/PBS. The brains expressing CD8::GFP in a single neuron of interest were imaged.

Confocal imaging and three-dimensional reconstructions of optical sections

Confocal serial optical images of the whole-mount brain were taken at 0.7–1 μm z-intervals with a Carl Zeiss confocal microscope LSM 700 equipped with water-immersion C-Apochromat 40×. Three-dimensional reconstruction and surface rendering were performed with Zeiss ZEN 2012 and Avizo 5.1, respectively. The brightness, color, and contrast of images were adjusted with Photoshop CS 5.1. For the left panels of Fig. 2d–f, the antibody signal levels of the fibers we analyzed were adjusted to increase the signal/noise ratio by changing the levels manually in Photoshop before the reconstructions. For the right panels of Fig. 2f, antibody signals except for the SCT1, such as the noise backgrounds on the surface of the brain were manually removed to visualize the GAL4 positive neuron more clearly.

Terminology

The spatial definition and nomenclature of each lobe and axonal tract is based on ref. 39. The layer divisions in the medulla and lobula are referred to ref. 40.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yagi, R. et al. Convergence of multimodal sensory pathways to the mushroom body calyx in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 6, 29481; doi: 10.1038/srep29481 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyoto Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, A. Ejima, T. Riemensperger, A. Fiala, and G. Struhl for kindly providing fly strains, and Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa for antibodies. We are deeply indebted to S. Takemura, M. Koizumi, Y. Hamanaka, and M. Mizunami’s lab members for helpful discussion and to M. Murakami and N. Onoda for maintaining fly stocks. This work was supported by PRESTO, Japan Science and Technology Agency, by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Grant number: 22770068, 24120509, and 26830026), and by Budget to Promote Executive Office Projects of Hokkaido University to N.K.T.

Footnotes

Author Contributions R.Y. and N.K.T. designed the project. R.Y., Y.M. and N.K.T. performed the experiments. R.Y., Y.M., M.M. and N.K.T. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Heisenberg M. Mushroom body memoir: from maps to models. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 266–275 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven-Ozkan T. & Davis R. L. Functional neuroanatomy of Drosophila olfactory memory formation. Learn. Mem. 21, 519–526 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopfer M. Central processing in the mushroom bodies. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 6, 99–103 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf R. et al. Drosophila mushroom bodies are dispensable for visual, tactile, and motor learning. Learn. Mem. 5, 166–178 (1998). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. et al. Distinct memory traces for two visual features in the Drosophila brain. Nature 439, 551–556 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y. et al. Differential roles of the fan-shaped body and the ellipsoid body in Drosophila visual pattern memory. Learn. Mem. 16, 289–295 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt K. et al. Shared mushroom body circuits underlie visual and olfactory memories in Drosophila. Elife 3, e02395 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt K. et al. Direct neural pathways convey distinct visual information to Drosophila mushroom bodies. Elife 5, e14009 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkhart C. & Scott K. Gustatory learning and processing in the Drosophila mushroom bodies. J. Neurosci. 35, 5950–5958 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R. F., Lienhard M. C., Borst A. & Fischbach K. F. Neuronal architecture of the antennal lobe in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res. 262, 9–34 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N. K., Endo K. & Ito K. Organization of antennal lobe-associated neurons in adult Drosophila melanogaster brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 520, 4067–4130 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronenberg W. Subdivisions of hymenopteran mushroom body calyces by their afferent supply. J. Comp. Neurol. 435, 474–489 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröter U. & Menzel R. A new ascending sensory tract to the calyces of the honeybee mushroom body, the subesophageal-calycal tract. J. Comp. Neurol. 465, 168–178 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A. et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2, 991–1001 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher N. J., Friedrich A. B., Lu Z., Tanimoto H. & Meinertzhagen I. A. Different classes of input and output neurons reveal new features in microglomeruli of the adult Drosophila mushroom body calyx. J. Comp. Neurol. 520, 2185–2201 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y. et al. The mushroom body of adult Drosophila characterized by GAL4 drivers. J. Neurogenet. 23, 156–172 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y. et al. The neuronal architecture of the mushroom body provides a logic for associative learning. Elife 3, e04577 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y. et al. Mushroom body output neurons encode valence and guide memory-based action selection in Drosophila. Elife 3, e04580 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D. D., Jouandet G. C., Kearney P. J., Macpherson L. J. & Gallio M. Temperature representation in the Drosophila brain. Nature 519, 358–361 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N. K., Suzuki E., Ejima A. & Stopfer M. Dye fills reveal additional olfactory tracts in the protocerebrum of wild-type Drosophila. J. Comp. Neurol. 520, 4131–4140 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A. M., Wang J. W. & Axel R. Spatial representation of the glomerular map in the Drosophila protocerebrum. Cell 109, 229–241 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. et al. The neural substrate of spectral preference in Drosophila. Neuron 60, 328–342 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. Y. et al. Mapping chromatic pathways in the Drosophila visual system. J. Comp. Neurol. 524, 213–227 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbering A. F. et al. Complementary function and integrated wiring of the evolutionarily distinct Drosophila olfactory subsystems. J. Neurosci. 31, 13357–13375 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallio M., Ofstad T. A., Macpherson L. J., Wang J. W. & Zuker C. S. The coding of temperature in the Drosophila brain. Cell 144, 614–624 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris S. M. Tritocerebral tract input to the insect mushroom bodies. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 37, 492–503 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden J. R., Skoulakis E. M., Han K. A., Kalderon D. & Davis R. L. Tripartite mushroom body architecture revealed by antigenic markers. Learn. Mem. 5, 38–51 (1998). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N. K., Tanimoto H. & Ito K. Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. J. Comp. Neurol. 508, 711–755 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino H. et al. Visual and olfactory input segregation in the mushroom body calyces in a basal neopteran, the American cockroach. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 41, 3–16 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M., Shimohigashi M., Tominaga Y., Arikawa K. & Homberg U. Topographically distinct visual and olfactory inputs to the mushroom body in the Swallowtail butterfly, Papilio xuthus. J. Comp. Neurol. 523, 162–182 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulk A. C. & Gronenberg W. Higher order visual input to the mushroom bodies in the bee, Bombus impatiens. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 37, 443–458 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. & Strausfeld N. J. Multimodal efferent and recurrent neurons in the medial lobes of cockroach mushroom bodies. J. Comp. Neurol. 409, 647–663 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J. B. et al. Associative learning disrupted by impaired Gs signaling in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Science 274, 2104–2107 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemensperger T., Völler T., Stock P., Buchner E. & Fiala A. Punishment prediction by dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 15, 1953–1960 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer B. D. et al. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9715–9720 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. & Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron 22, 451–461 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer B. D. et al. Refinement of tools for targeted gene expression in Drosophila. Genetics 186, 735–755 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klagges B. R. et al. Invertebrate synapsins: a single gene codes for several isoforms in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 16, 3154–3165 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K. et al. A systematic nomenclature for the insect brain. Neuron 81, 755–765 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach K. F. & Dittrich A. P. M. The optic lobe of Drosophila melanogaster. I. A Golgi analysis of wild-type structure. Cell Tissue Res. 258, 441–475 (1989). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.