Abstract

Phyllody is a flower abnormality in which leaf-like structures replace flower organs in all whorls. Here, we investigated the origin and the molecular mechanism of phyllody phenotype in Rosa chinensis cv. Viridiflora, an ancient naturally occurring Chinese mutant cultivar. Reciprocal grafting experiments and microscopy analyses, demonstrated that the phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is not associated with phytoplasmas infection. Transcriptome comparisons by the mean of RNA-Seq identified 672 up-regulated and 666 down-regulated genes in Viridiflora compared to its closely related genotype R. chinensis cv. Old Blush. A fraction of these genes are putative homologs of genes known to be involved in flower initiation and development. We show that in flower whorl 2 of Viridiflora, a down-regulation of the floral organ identity genes RcPISTILLATA (RcPI), RcAPETALA3 (RcAP3) and RcSEPALLATA3 (RcSEP3), together with an up-regulation of the putative homolog of the gene SUPPRESSOR of OVEREXPRESSION of CONSTANS1 (RcSOC1) are likely at the origin of the loss of petal identity and leaf-like structures formation. In whorl 3 of Viridiflora, ectopic expression of RcAPETALA2 (RcAP2) along with the down regulation of RcPI, RcAP3, and RcSEP3 is associated with loss of stamens identity and leaf-like structures formation. In whorl 4, the ectopic expression of RcAP2 associated with a down-regulation of RcSEP3 and of the C-class gene RcAGAMOUS correlate with loss of pistil identity. The latter also suggested the antagonist effect between the A and C class genes in the rose. Together, these data suggest that modified expression of the ABCE flower organ identity genes is associated with the phyllody phenotype in the rose Viridiflora and that these genes are important for normal flower organs development.

Keywords: rose, Viridiflora, phyllody, transcriptome analysis, ABC flower organ’s identity genes, RcSOC1

Introduction

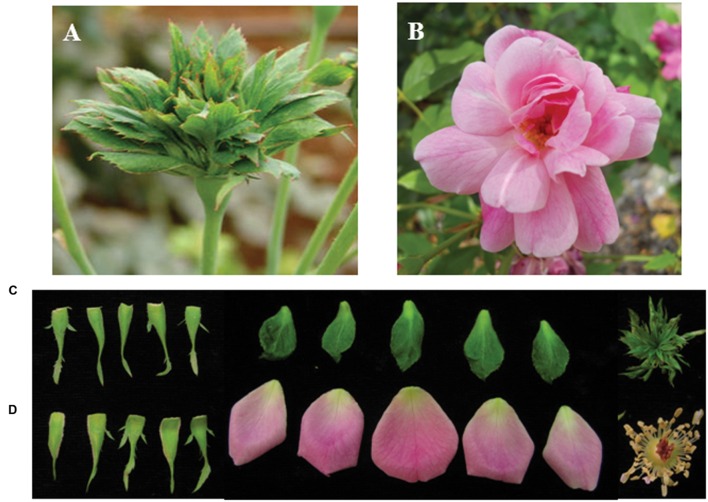

Roses have been cultivated by humans since antiquity, as early as 3 000 B.C. in China. Today there exist more than 35 000 rose cultivars. These modern rose cultivars were established from less than 10 rose species, including Chinese species (Wylie, 1954; Liu, 1964). Chinese old roses have high ornamental, cultural, economic values, and represent an important rose germplasms resource (Zhang and Zhu, 2006; Yan et al., 2014). Among old Chinese rose species, the recurrent blooming Rosa chinensis was used in many breeding programs to select for the most advantageous traits such as recurrent blooming, scent and resistance to pathogens (Martin et al., 2001; Ku and Robertson, 2003; Bendahmane et al., 2013). R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora (hereafter Viridiflora) is a rose cultivar, commonly known as the ‘green rose’ (Chmelmitsky et al., 2002), in which petals, stamens and pistils are converted into leaf-like organs (Figures 1A,C). This phenomenon is also known as phyllody, a phenotype that has been described in many plant species (Meyer, 1966; Mor and Zieslin, 1992). Viridiflora is a spontaneous mutant of R. chinensis Jaquin (Krussman, 1981). This stable mutant has been maintained for over 200 years in China, Europe and America, and is widely used for ornamental horticulture.

FIGURE 1.

Flower phenotype of Rosa chinensis cv. Viridiflora (A,C) and Old Blush (B,D). (C,D) Dissected flower organs of Viridiflora and Old Blush, respectively.

The prevailing ABCE genetic model of floral organ identity determination, with the combinatorial activity of four classes of homeotic genes (A, B, C, and E), has been widely characterized in many flowering species. Most of the ABCE genes encode MADS-box transcription factors (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Smaczniak et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, the class A-class genes APETALA1 (AP1) and APETALA2 (AP2) specify sepal organ identity and development; A-class genes and the B-class genes APETALA3 (AP3) and PISTILLATA (PI) together determine petal organ identity and development; B-class genes together with the C-class gene AGAMOUS (AG) are required for stamen formation and the C-class gene AG is required for carpel formation (Weigel and Meyerowitz, 1994). The E-class genes SEPALLATA (SEP1, SEP2, SEP3, SEP4) interact with A, B, and C class genes and are involved in specifying floral organs in all flower whorls. The ABCE model is relatively conserved in the flowering plants with few variations (Heijmans et al., 2012; Smaczniak et al., 2012; Wellmer et al., 2014).

In Rosa sp., homologs of A-class (RhAP1, RhAP2), B-class (RhAP3, RhPI), C-class (RhAG) and E-class genes have been reported (Dubois et al., 2012; Bendahmane et al., 2013). Expression analysis and overexpression experiments of these rose MADS-encoding cDNAs in Arabidopsis suggested their role in flower organ identity determination in the rose (Kitahara and Matsumoto, 2000; Kitahara et al., 2004; Hibino et al., 2006; Dubois et al., 2010, 2011, 2012; Ma et al., 2015).

In Arabidopsis, loss of function of A, B, or C genes lead to homeotic conversion of floral organs and floral aberrations that are different from the phyllody-like phenotype (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991). In the rose it was demonstrated that misexpression or down-regulation of the RhAG in whorl 3 was associated with homeotic conversion of stamens to petals and double flower formation (Dubois et al., 2010). In Arabidopsis, the triple SEP1/2/3 mutant produces flowers in which all organs develop as sepals (Pelaz et al., 2000). It was also reported in many plants that, infection by phytoplasmas was also reported to lead to phyllody (McCoy et al., 1989; Szyndel, 2003; Hogenhout et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis, it was recently shown that the phytoplasma-secreted protein PHYL1 is involved in the targeted protein degradation of the organ identity proteins SEP3 and AP1, which in turn lead to the transformation of flower organs into leaf-like structures (Maejima et al., 2014, 2015).

In this study, we addressed the cause of phyllody phenotype in the rose Viridiflora. We show that phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is not caused by Mycoplasma like organism (MLO) infection. To identify the molecular basis of the malformed flowers in Viridiflora, we used a transcriptomic approach to compare gene expression in flowers of R. chinensis cv. Old Blush (hereafter Old Blush) and Viridiflora. Our study identified that the green flower phenotype (phyllody) in R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora is associated with misexpression of the putative homologs of the flowering integrator RcSOC1 and of ABCE flower organ identity genes RcAP1, RcAP2, RcPI, RcAG, and RcSEP3.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Grafting Experiment

Rosa chinensis cv. Old Blush (Figures 1B,D) and its variant R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora, in which petals, stamens, and pistils are converted to leaf-like organs (Figures 1A,C), were field-grown in Flower Research Institute of Yunnan, Academy of Agricultural Science. A part from the phyllody phenotype, no other phenotypic differences were observed between Old Blush and Viridiflora (Figures 1A,C). Flower buds at stage 8–10 mm were collected and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until RNA extraction.

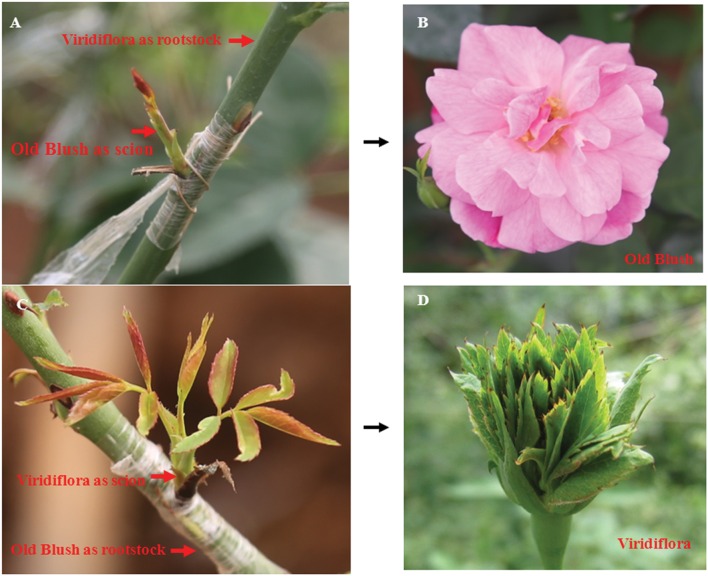

Grafting experiments were performed as previously described (Ohkawa, 1980). Old Blush young shoots, used as scion, were grafted on Viridiflora plants used as rootstock. As control Viridiflora young shoots, used as scion, were grafted on Old Blush plants used as rootstock (Figures 2A,C). Twenty shoot grafting experiments were performed for each.

FIGURE 2.

Grafting does not lead to modified floral phenotype of Viridiflora and Old Blush. (A,B) Shoots of Old Blush were grafted on Viridiflora used as rootstock. Mature flower of Old Blush with Viridiflora as rootstock show wild-type Old Blush flower phenotype (B); (C,D) Shoots of Viridiflora were grafted on Old Blush used as rootstock. Mature flower of Viridiflora with Old Blush as rootstock show phyllody phenotype (D).

Microscopy and PCR Experiment to Detect Mycoplasma

To detect mycoplasma, samples of about 2 mm2 were cut from young flower buds, then crude sap extracts were prepared from these tissues in 0.01 M potassium phosphate pH 7.0 buffer and then applied to 4% Formvar-coated, carbon-stabilized copper grids (300 mesh). Grids were then stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 10 s, rinsed with 0.01 M potassium phosphate pH 7.0 buffer and water (Yin et al., 2014). Grids were dried and examined on a JEM-100CX II transmission electron microscope (JOEL, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Total DNA was extracted from young flower buds using Plant DNA Isolation Reagent (TakaRa, China) and then used to PCR amplify MLO DNA using the MLO specific primers R16mF/R16mR (Lee et al., 1993; Supplementary Table S1). A construct harboring MLO DNA was used as positive control.

Library Construction and RNA-Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and contaminating DNA was then removed by treatment with RNase-free DNase. NanoDrop and Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer were used to quantify the total RNA before RNA-Seq library construction.

Transcriptome libraries of Viridiflora and Old Blush were constructed using Illumina TruSeq RNA sample preparation Kit V2 following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, total RNA was purified using Magnetic Oligo (dT) beads. Then, purified RNA was sheared to approximately 330 nucleotides fragments and primed for cDNA synthesis using random primers. Subsequently, the fragments were ligated to sequencing adapters. Using agarose gel electrophoresis, the suitable fragments with 400–500 nt sizes were selected as templates for PCR amplification and the final PCR products were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2500 system as 125 nt, paired-end Illumina reads.

Transcriptome Assembly and Annotation

High-quality transcript sequences were obtained by de novo transcriptome assembly of the RNA-seq reads, using Trinity software (version: r20140413p1; Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) with default parameters. Open reading frame (ORF) identification was identified using Transdecoder (Grabherr et al., 2011) with default parameters. Homology sequences search was performed against the UniProt databases by ncbi-blast-2.2.27+ with an E-value of 10-6. The GO terms were assigned to each assembled sequences based on the UniProt databases. The all information of transcriptome data is available in the database1

Gene Expression Analysis and DEG Identification

The read counts for each transcript were calculated after aligning the RNA-Seq reads on the assembled transcriptome using Bowtie2 2.1.0 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). To accurately measure gene expression level, we only retained pairs of reads having both ends matching on the same transcript. The expression level of each transcript was normalized as the fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM), which is analogous to single-read RPKM for single reads (Mortazavi et al., 2008). The P-value were calculated according to the statistical R package DEGseq (Wang et al., 2010) using MA-plot-based method with random sampling model. Then, the differentially expressed genes were identified using fold-change >3 and a P < 0.001 as the threshold.

Validation of Differential Expressed Genes

The sequences of the genes used for qRT-PCR validation were provided (details listed in Supplementary Data Sheet S1). Gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) were designed using Primer32 Total RNAs were extracted from leaves and from sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils at 8–10 mm flower buds development stage using TRIzol RNA purification kit (TaKaRa, China). One microgram of total RNA was used in reverse transcription in a total reaction volume of 20 μL in the presence of 6-mer random primers and an oligo primer according to the protocol provided by manufacturer TaKaRa (Yan et al., 2011). The standard curve for each gene was obtained by real-time PCR with five dilutions of cDNA. The reactions were performed in 20 μL volumes each containing 10 μL 2× SYBR Green Mastermix (TaKaRa), 300 nM of each primer and 2 μL of 10-fold diluted cDNA template (Yan et al., 2014). The PCR reactions were run in a Bio-Rad Sequence Detection System. Three biological replicates were performed for each analysis. RhGAPDH (AB370120) was used as control. Quantification of gene relative expression in different organs was performed using the delta-delta Ct method as described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001). All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) after normalization.

Results

Phyllody Phenotype of R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora Is Not Associated with Phytoplasma

Viridiflora refers to a floral aberration in which petals, stamens, and pistils are converted to leaf-like organs (Figures 1A,C) a phenotype that resembles phytoplasmas infection-induced phyllody phenotype. Phytoplasmas are non-cultivable microorganisms transmitted by contact with infected plants. The grafting mechanical contact between the rootstock and the scion enables the spread of this disease and this approach is used generally to detect phytoplasmas (Golino et al., 1989; Aldaghi et al., 2007; Goldschmidt, 2014). To address if Viridiflora was associated with mycoplasma infection, we used grafting approach in which Viridiflora was used as rootstock and healthy Old Blush was used as scion (Figure 2A) and vice versa, used as control (Figure 2C). Twenty bud grafting experiments were performed for each. These data showed that all Old Blush buds with Viridiflora as rootstock bloomed normally and flower organs phenotype was identical to non-grafted Old Blush control plants (Figure 2B). At the same time, all Viridiflora flowers with Old Blush as rootstock exhibited phyllody phenotype similar to the none grafted Viridiflora control plants (Figure 2D). It should be noted that flowers of Old Bush used as rootstock, showed no phyllody phenotype. These data suggest that phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is not a result of phytoplasma infection. In agreement with these data, transmission electron microscopy or PCR experiments identified no trace of phytoplasma or phytoplasma DNA respectively, in young buds of Viridiflora and Old Blush (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). Taken together these data strongly suggest that the flower mutant phenotype of Viridiflora was not caused by phytoplasma infection.

Flower Buds Transcriptome Comparison in Viridiflora and Old Blush

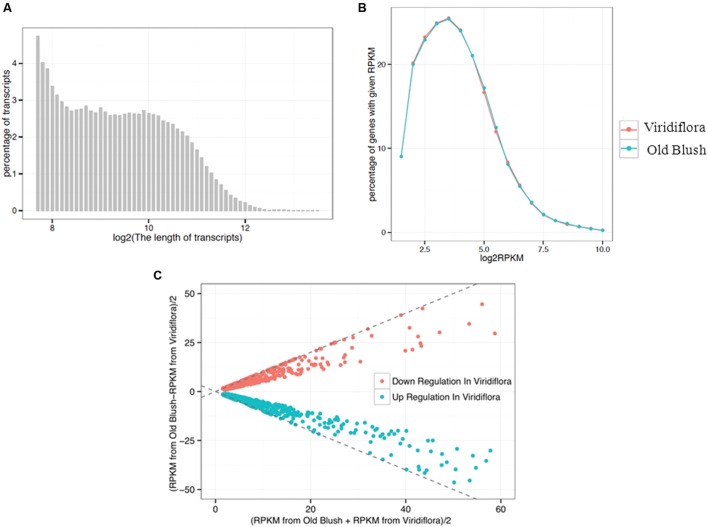

To investigate further the molecular basis of the phyllody phenotype, we compared the transcriptome in flowers of Viridiflora and Old Blush. Total RNA was prepared from flower buds at 8–10 mm development stage and then used to build two libraries for high-throughput sequencing. A total of 40 and 44 million reads were generated from Viridiflora and Old Blush samples, respectively. The transcriptome assembly sequences of R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora has been deposited at the Database of Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession GETJ00000000. The transcriptome data are available in the database1. In total, five gigabase for each library were produced. Paired-end reads were assembled into transcript sequences and yielded 68,565 unisequences with an average length of 887 bp (Figure 3A). Approximately 91% of the reads from Viridiflora and Old Blush could be successfully aligned to the assembled transcripts, used as reference sequences (Table 1). In total, over 32,224,620 and 34,200,388 reads were mapped back in pairs with the unique location for Viridiflora and Old Blush libraries, respectively (Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Sequence length distribution of assembled transcripts (A), plotting distribution of log-transformed FPKM (Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) values (B) and MA-plot for differential expressed genes (C). (A) Displays the distribution of transcripts length range. (B) Shows the percentage of genes with a given FPKM value. (C) Shows the differential expressed genes. The X-axis indicates the value of [FPKM from Old Blush + FPKM from Viridiflora]/2, and the Y-axis indicates the value of [FPKM from Old Blush – FPKM from Viridiflora]/2.

Table 1.

Summary of Illumina sequencing and assembly for two RNA-Seq libraries.

| Sample | Reads (PE) | Length | Total bases | GC% | Mapping (ratio) | Unique (ratio) | FPKM > 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viridiflora | 20,640,280 × 2 | 125,125 | 5,160,070,000 | 46,46 | 37,697,457(91%) | 16,112,310 × 2(78%) | 20,017 |

| Old Blush | 22,052,225 × 2 | 125,125 | 5,513,056,250 | 46,46 | 39,996,389(91%) | 17,100,194 × 2(78%) | 20,859 |

PE, paired-end reads; FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped.

Pairs of reads with a unique location were then used to estimate genes expression levels. Read counts were normalized as FPKM (Mortazavi et al., 2008) and genes with a minimum expression threshold corresponding to FPKM > 3 were kept. In total, 20,017 and 20,859 genes were considered as expressed in the libraries of Viridiflora and Old Blush, respectively (Table 1). The average FPKMs for Viridiflora and Old Blush were 33.18 and 32.57, respectively (Figure 3B).

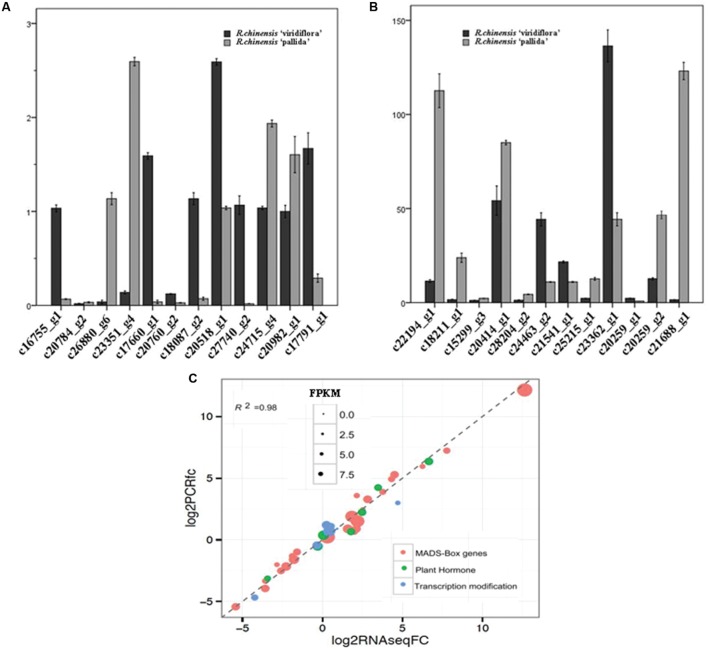

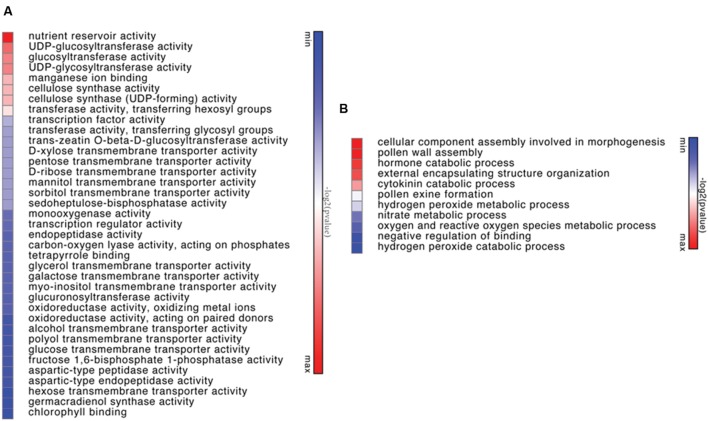

Genes differentially expressed between of Viridiflora and Old Blush were investigated using the MA-plot-based method with the random sampling model (Wang et al., 2010). 672 unisequences were up-regulated and 666 were down-regulated (Figure 3C) in Viridiflora compared to Old Blush, with a fold change of at least 3 and a P-value < 0.001 (Table 1). Flower development genes that exhibited significant expression difference between Old Blush and Viridiflora were for RT-qPCR validation. Expression of 24 genes among the differentially expressed genes was analyzed using RT-qPCR (Figures 4A,B). A good correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.98) between RT-qPCR data and the RNA-Seq data was observed for the 24 analyzed genes, suggesting that our transcriptomics data are accurate in the different tissues and experimental conditions (Figure 4C). GO enrichment analysis showed that transcription factors were enriched in the up-regulated genes fraction, while GO terms associated with ‘pollen wall assembly,’ ‘pollen exine formation,’ and ‘hormone catabolic process’ were enriched in the down-regulated genes fraction (Figures 5A,B).

FIGURE 4.

Expression analyses of selected genes. (A,B) Real time quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) expression analyses of transcripts selected in silico. (C) Correlation of qPCR (Y axis) and RNA-Seq (X axis) data for selected genes (involved in flowering and flower organs initiation and development) that exhibited differential expression between in R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora with Old Blush.

FIGURE 5.

Heapmat representation of significant functional groups of up-regulated genes in Viridiflora (P-value < 0.05) by molecular function (A) or by biological function (B). Colors show the value of log2 (P-value), with green representing low P-value and red representing high P-value.

The expressions of the rose homologs of the flower development genes PI (c20259_g2), AG (c18211_g1), AGL9 (c26880_g6), AGL15 (c24715_g4; Table 2), Pollen-specific protein SF3 (Baltz et al., 1992; c15299_g3) and Gibberellin 20 oxidase 1 (c25215_g1; Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1991; Goto and Pharris, 1999) were significantly repressed in Viridiflora compared to Old Blush (Table 2). Genes expressions of putative homologs of other flower development transcription factors, such as AP1 (c16755_g1), AP2 (c27740_g2), SOC1 (c24463_g2), AGL6 (c17791_g1), AGL8 (c17660_g1; Table 2) were in contrast up-regulated in Viridiflora flowers compared to Old Blush flowers. In addition, the bHLH transcription factor UNE10 (Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003; c18395_g2) and homeotic gene BEL1 (c20518_g1) were also significantly up-regulated (Table 2). BEL1 is known to act as negative regulator of AG and has a major role in ovule patterning and in determination of integument identity via its interaction with MADS-box factors (Ray et al., 1994; Mizumoto et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2014). Taken together these data show that the phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is mainly associated with modified expression of flowering and flower development related genes.

Table 2.

Genes known to be involved in flower initiation and development, showing either up- or down-regulated expression levels in R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora.

| Gene ID no. | Description | FPKM fold change | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | |||

| c24463_g2 | MADS-box protein SOC1 | 7.26 | 1.89e-11 |

| c17716_g1 | Auxin-responsive protein IAA26 | 10.81 | 9.79e-33 |

| c18087_g2 | MADS-box protein SOC1 | 11.71 | 2.97e-21 |

| c16755_g1 | Floral homeotic protein APETALA 1 | 11.91 | 7.32e-104 |

| c20554_g1 | Cytochrome P450 | 18.81 | 1.76e-68 |

| c20760_g2 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF105 | 4.81 | 3.06e-104 |

| c18395_g2 | Transcription factor UNE10 | 19.88 | 2.17e-42 |

| c27740_g2 | Floral homeotic protein APETALA2 | 3.43 | 3.67e-28 |

| c17660_g1 | Agamous-like MADS-box protein AGL8 | 42.98 | 5.07e-118 |

| c20518_g1 | Homeobox protein BEL1 | 3.68 | 1.65e-12 |

| c18389_g2 | Auxin-binding protein ABP19 | 83.77 | 0 |

| c17791_g1 | Agamous-like MADS-box protein AGL6 | 6.03 | 4.61e-33 |

| Down-regulated | |||

| c18211_g1 | Floral homeotic protein AGAMOUS | 13.63 | 1.20e-43 |

| c19619_g1 | Transcription repressor MYB4 | 218.60 | 2.55e-49 |

| c26880_g6 | Agamous-like MADS-box protein AGL9 | 20.10 | 1.59e-28 |

| c24715_g4 | ABC transporter G family member 15 | 3.01 | 5.94e-130 |

| c20259_g2 | Floral homeotic protein PI/GLO | 3.59 | 0 |

| c15299_g3 | Pollen-specific protein SF3 | 4.36 | 8.21e-25 |

| c21688_g1 | Gibberellin 20 oxidase 1 | 100.50 | 3.24e-144 |

| c22194_g2 | Floral homeotic protein AGAMOUS | 7.10 | 4.99e-38 |

| c20259_g1 | Floral homeotic protein FBP1 | 4.59 | 0 |

| c19919_g1 | Transcription factor MYB44 | 76.32 | 7.49e-20 |

| c28204_g2 | Agamous-like MADS-box protein AGL15 | 3.60 | 3.86e-15 |

| c20414_g1 | Auxin response factor 8 | 4.0 | 4.03e-05 |

| c20982_g1 | IAA-amino acid hydrolase ILR1 | 3.43 | 4.51e-48 |

| c25215_g2 | Transcriptional corepressor LEUNIG | 17.27 | 6.95e-13 |

| c18107_g1 | Stamen-specific protein FIL1 | 6421.30 | 0 |

| c22194_g1 | Floral homeotic protein AGAMOUS | 7.11 | 3.86e-54 |

Expression Profiles of MADS-Box Transcription Factor Coding Genes

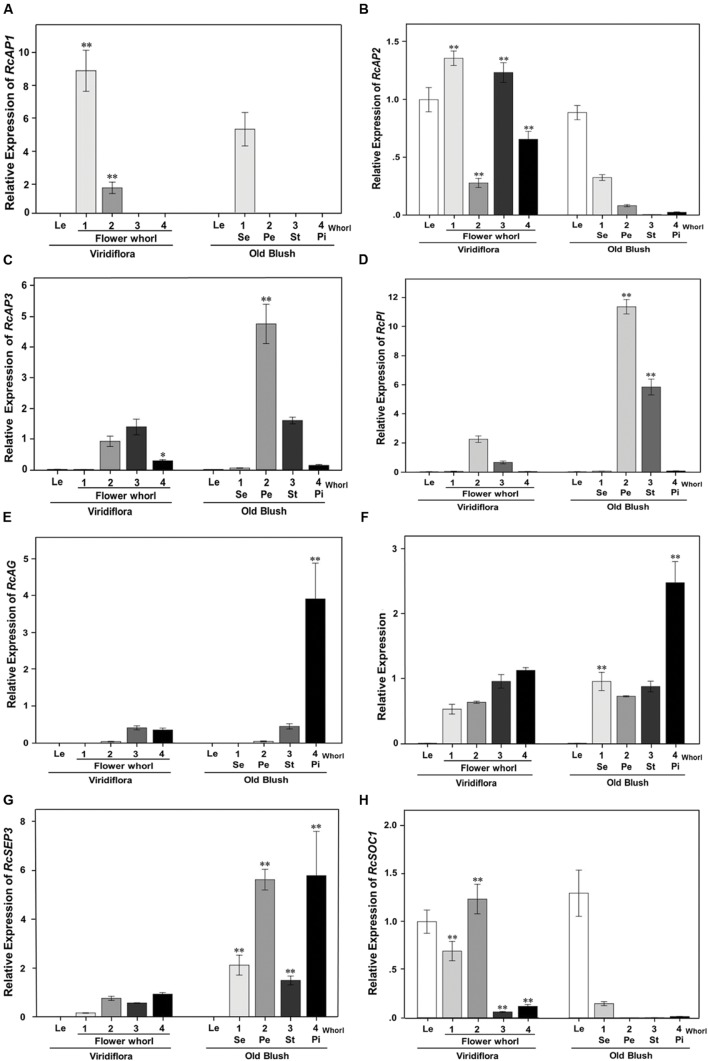

To further investigate the origin of the phyllody phenotype, the expression of MADS-box flower organ identity genes RcAP1 (c16755_g1), RcAP2 (c27740_g2), RcPI (c20259_g2), RcAP3 (RC000216; Dubois et al., 2012), RcAG (c18211_g1), RcSEP1 (RC001958; Dubois et al., 2012), and RcSEP3 (RC000799; Dubois et al., 2012) and flowering RcSOC1 (c24463_g2) were analyzed using RT-qPCR in leaves and in sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils whorls of developing flowers of Viridiflora and Old Blush.

In wild-type flowers of Old Blush, the A-class genes RcAP1 mRNA (c16755_g1) accumulated to high levels in whorl 1 (sepals) and showed very low or no expression in whorls 2 (petals), 3 (stamens), and 4 (pistils; Figure 6A), thus in agreement with previously published data in Arabidopsis (Gustafson-Brown et al., 1994). mRNA of the A-class RcAP2 was expressed in whorls 1 and 2 of Old Blush (sepal and petal, respectively; Figure 6B) and showed relative low expression level in the fourth whorls (pistil; Figure 6B), thus similar to previously reported data in Arabidopsis (Jofuku et al., 1994). The B-class genes RcPI and RcAP3 were expressed in second and third whorls (petals and stamens respectively) of Old Blush (Figure 6C), thus similar pattern as their Arabidopsis counterparts, PI and AP3 (Krizek and Meyerowitz, 1996). As expected, the C-class gene RcAG (c18211_g1) was expressed in stamens (whorl 3) and in pistils (whorl 4) of Old Blush. The organ identity RcSEP1 and RcSEP3 were expressed in all floral whorls (Figures 6F,G). In Arabidopsis, SEP1 is expressed in all whorls while SEP3 is expressed in whorls 2, 3, and 4. These data together suggest that the ABCE genetic model of floral organ identity determination is likely conserved in the rose.

FIGURE 6.

Quantitative RT-PCR expression analyses of genes involved in flowering and in flower organ identity determination and development. Expression of RcAP1(c16755_g1; A), RcAP2 (c27740_g2; B), RcAP3 (RC000216; C), RcPI (c20259_g2; D), RcAG (c18211_g1; E), RcSEP1(RC001958; F), RcSEP3 (RC000799; G), and RcSOC1(c24463_g2; H) was analyzed in developing flower buds, at stage 8–10 mm, of Viridiflora and Old Blush. Le, leaves; 1–4, Flower whorls; Se, sepals; Pe, petal; St, stamens; Pi, pistils. Values are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences calculated using Tukey’s test (∗∗P < 0.01; ∗P < 0.05).

In Viridiflora flowers, the expression of RcAP1 was significantly increased in the sepal and petal whorls (Figure 6A). RcAP1 expression was about 1.7 times induced in whorl 1 and strikingly 20-fold induced in whorls 2 compared to that in Old Blush. The expression of RcAP2 was up-regulated in all whorls of Viridiflora flowers. Interestingly, the expression of RcAP2 was significantly up-regulated in stamens and pistils whorls of Viridiflora (Figure 6B) and conversely the expression of the C-class gene RcAG was significantly down-regulated in whorl 4 compared to that in Old Blush (Figure 6E). It should be noted that RcAG was about eightfold over-expressed in the pistils compared to stamens (Figure 6E). These data are also in agreement with the antagonist effect between A and C functions, known as crucial in floral patterning (Gustafson-Brown et al., 1994). Furthermore, RcSEP3 mRNA was about sixfold under-expressed in all flower whorls of Viridiflora compared to Old Blush (Figure 6G). However, the expression of RcSEP1 was not strikingly different between the two roses, except for a relative low expression level in whorl 4 (pistils) of Viridiflora compared to Old Blush (Figure 6F). The phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora was also associated with significant down-regulation of the B class genes RcP1 and RcAP3 in the petals and stamens whorls (2 and 3, respectively) compared to Old Blush (5- and 6-fold, respectively; Figures 6C,D).

Interestingly, in Viridiflora, the expression of the flowering time integrator MADS-box RcSOC1 gene was induced in petals, stamens and pistils whorls, with the strongest expression in sepals and in petals whorls (Figure 6H). In Old Blush, the expression of RcSOC1 was confined to leaves and although at lower levels to sepals as well, thus a similar pattern as in Arabidopsis (Samach et al., 2000).

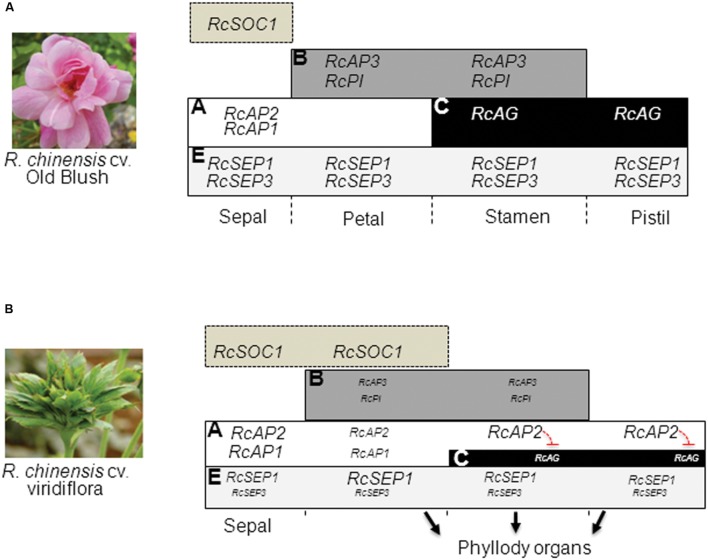

To summarize, these data show that in whorl 2, the loss of petal identity is consistent with the down-regulation of the B (RcPI and RcAP3) and E-class (RcSEP3) organ identity genes. The loss of petal organ identity combined with the strong up-regulation of RcSOC1 is likely associated with the conversion of petals into leaf-like structures in whorl 2. In whorls 3 and 4, the ectopic expression of the A-class RcAP2 and the down-regulation of the E-class RcSEP3 in combination with the down regulation of B-class genes RcPI and RcAP3 in whorl 3 and of the C-class RcAG in whorl 4 is consistent with the observed loss of stamens and pistils identity, respectively, and their conversion into leaf-like structures.

Discussion

Phyllody is a flower abnormality in which leaf-like structures replace flower organs. Two types of phyllody were described in the genus Rosa. The first type of phyllody (R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora) is a stable mutation known as the ‘green rose’ characterized by the transformation of all flower organs to leaf-like structures (Krussman, 1981). For the second type, described in R. x hybrida cv. Motrea, phyllody is restricted to reproductive organs (third and fourth whorls; Mor and Zieslin, 1992). It was suggested that Viridiflora phenotype might be caused by phytoplasma infection (McCoy et al., 1989; Szyndel, 2003; Zhang and Zhu, 2006). Here we used grafting, transmission electron microscopy and PCR experiments, to demonstrate that phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is not associated with phytoplasma infection (Figure 2).

Gene expression analysis in flowers early during development, showed that the phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is associated with ectopic expression of the flowering time gene RcSOC1 and with misexpression of the ABCE flower organ identity genes leading to loss of petal, stamen and pistil organ identity (Figure 7). These data indicate that in Viridiflora a shift of the expression of the A-class gene RcAP2 toward the third and fourth whorls together with significantly reduced expression of B, C, and E gene classes are associated with the observed phyllody phenotype. These data also highlights the antagonist effect of the A and C class gene.

FIGURE 7.

Model for Viridiflora phenotype formation. (A) wild-type ABCE model and expression of flower organ identity genes. (B) In Viridiflora the conversion of petals into leaf-like structures in whorl two is associated with the down-regulation of petal organ identity genes RcAP3, RcPI, and RcSEP3 combined with up-regulation of RcSOC1. In the third and fourth whorls the conversion of stamens and pistils to leaf-like structures is associated with a shift of A-class gene RcAP2 expression domain together with down-regulation of E class gene RcSEP3 and down-regulation of B (RcAP3 and RcPI), and C (RcAG). The down-regulation of gene expression is indicated with text of smaller size.

The A-class gene AP1 is known to be involved in sepal and petal organ identity determination. In R. chinensis cv. Old Blush, RcAP1 showed high expression levels in developing sepals and low expression levels in developing petals (Figure 6A). Similar data were observed in R. hybrida (Mibus et al., 2011) and in other flowering plant species (Huijser et al., 1992; Mandel et al., 1992). Interestingly, we observed a strong down-regulation of the B-class genes RcPI and RcAP3 in petals and stamens whorls and of the E class gene RcSEP3 in all whorls. In Arabidopsis genetic and gene expression experiments showed that SEP3 is required for the up-regulation of B and C floral homeotic genes (Castillejo et al., 2005; Kaufmann et al., 2009). It is possible that the downregulation of RcAP3 and RcPI is a result of reduced expression of RcSEP3. In the flowering plants, mutation of the B-class genes leads to conversion of petals into sepals. In Viridiflora the down-regulation of RcPI and RcAP3 cannot explain the leaf-like phenotype of stamens in Viridiflora. It is likely that the up-regulation of SOC1 in the context of the B (RcPI and RcAP3) and E (RcSEP3) genes down-regulation are at least in part at the origin of the loss of petal identity and phyllody phenotype. In whorl 3, the up-regulation of RcAP2 and the down regulation of RcPI, RcAP3 and RcSEP3 are likely at the origin of loss of stamen identity and phylloid organs formation.

AGAMOUS (AG), the C-class floral homeotic gene is involved in the specification of stamens and pistils identity and the termination of the floral meristem in the center of the flower (Kapoor et al., 2002; ÓMaoiléidigh et al., 2013). In Viridiflora, our data show that mRNA of RcAG was down-regulated in stamens and pistils, compared to Old Blush (Figure 6D). In Arabidopsis the down-regulation of AG leads to conversion of stamens into petals (Yanofsky et al., 1990). Similarly, the silencing of pMADS3, a petunia C-class gene, resulted in homeotic conversion of stamens into petaloid structures (Kapoor et al., 2002). Interestingly, in the ranunculid Thalictrum thalictroides, down-regulation of the AG homolog ThtAG1 by the mean of virus-induced gene silencing resulted in homeotic conversion of stamens and pistils into sepaloid organs and loss of flower determinacy (Galimba et al., 2012). We observed that the putative homolog of BEL1 is up-regulated in Viridiflora flowers. In Arabidopsis BEL1 was shown to act as negative regulator of AG (Ray et al., 1994; Sharma et al., 2014). Therefore, we cannot rule out that the down-regulation of RcAG could be a consequence of increased RcBEL1 levels. In addition, RcAP2 showed ectopic expression in stamens and pistils of Viridiflora (Figure 6B). This result was not surprising, as it is known that AP2 is a negative regulator of AG expression in the first two whorls of the flower (Drews et al., 1991). Therefore, it is likely that in Viridiflora the ectopic expression of RcAP2 in stamens and pistils whorls lead to the observed down-regulation of RcAG expression in whorl 4. It has been reported in Arabidopsis that AP2, besides its antagonist role with the C-class gene AG, is also involved in repressing B-class genes AP3 and PI by regulating their outer boundary expression (Krogan et al., 2012; Wuest et al., 2012). It is likely that similar role is conserved in the rose and that in Viridiflora the up-regulation of RcAP2 in whorl 3 (Figure 6B) is responsible for the observed down-regulation of the B-class genes RcAP3 and RcPI (Figures 6C,D) and thus loss of petal and stamens organ identity.

We show that the phyllody phenotype in Viridiflora is associated with ectopic expression of the putative homolog of the flowering time integrator gene SOC1. In Arabidopsis SOC1 plays a central role to integrate the photoperiodic, the autonomous, the vernalization, and the gibberellin pathways during flowering (Borner et al., 2000; Samach et al., 2000; Moon et al., 2003). SOC1-like genes are preferentially expressed in vegetative parts of both angiosperms and gymnosperms (Tandre et al., 1995; Winter et al., 1999; Watson and Brill, 2004), but examples of SOC1-like genes expressed in reproductive organs have also been reported (Heuer et al., 2001). AtSOC1 is mainly expressed in meristems and developing leaves (Samach et al., 2000). Over-expression of AtSOC1-like genes causes early flowering in several plant species (Tadege et al., 2003; Ferrario et al., 2004; Smykal et al., 2007). Interestingly, it has also been shown that over-expression of GhSOC1 in gerbera leads to a partial loss of floral organ identity, but did not affect flowering time (Ruokolainen et al., 2010, 2011). In petunia, ectopic expression of UNSHAVEN (petunia SOC1 homolog) leads to conversion of petals to organs with leaf-like features (Ferrario et al., 2004). Here, we also show that in the rose similar conversion of petals to leaf-like structures is also associated with ectopic expression of RcSOC1. In Arabidopsis SOC1 has been shown to regulate the flower meristem identity gene LEAFY (LFY; Lee et al., 2008). LFY links floral induction and flower organs identity determination and development via induction of the ABC genes. Whether in the rose RcSOC1 acts in similar pathway this remains to be addressed.

Conclusion

Taken together, our data with those in the literature suggest that the phyllody phenotype in the rose Viridiflora is associated with an up-regulation and ectopic expression of RcSOC1 and of the A-class flower organ identity genes along with the down-regulation of the B, C, and E floral organ identity genes. Therefore, these data here represent a base for future research to deeply understand the molecular mechanisms associated with ABCE organ identity genes, and the origin of type 1 phyllody phenotype in roses.

Author Contributions

HY, MB, and KT designed the entire research. HY, HZ, QW, HJ, and XQ performed experiments and helped to analyze data. LG and OR analyzed transcriptome data. SB, JJ, and JW revised the manuscript. HY and MB wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National 863 project (2011AA100208) and by fund from the Natural Science Foundation of China (31360492 and 31560301) and Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China (2013FB093).

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00996

FIGURE S1 | Electron-microscopic analysis of sap extracts from young buds at stage 8–10 mm of R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora (A) and Old Blush used as negative control (B). The samples were negatively stained and analyzed at a magnification of ×100 000. The bar represents 100 nm. No trace of mycoplasma is observed in Viridiflora or Old Blush samples.

FIGURE S2 | No trace of MLO DNA is found in Viridiflora and Old Blush: DNA was prepared from buds at stage 8–10 mm of R. chinensis Viridiflora and Old Blush and then used to PCR amplify MLO DNA. M, molecular marker; C, positive control using MLO plasmid; 1,Viridiflora DNA; 2,Old Blush DNA.

TABLE S1 | Primers used for real-time quantitative PCR.

DATA SHEET S1 | The sequences of genes used for qRT-PCR validation.

References

- Aldaghi M., Massart S., Roussel S., Steyer S., Lateur M., Jijakli M. H. (2007). Comparison of different techniques for inoculation of “Candidatus Phytoplasma mali” on apple and periwinkle in biological indexing procedure. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 72 779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz R., Domon C., Pillay D. T. N., Steinmetz A. (1992). Characterization of a pollen-specific cDNA from sunflower encoding a zinc finger protein. Plant J. 2 713–721. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1992.t01-13-00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendahmane M., Dubois A., Raymond O., Le Bris M. (2013). Genetics and genomics of flower initiation and development in roses. J. Exp. Bot. 64 847–857. 10.1093/jxb/ers387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner R., Kampmann G., Chandler J., Gleissner R., Wisman E., Apel K., et al. (2000). A MADS domain gene involved in the transition to flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 24 591–599. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillejo C., Romera-Branchat M., Pelaz S. (2005). A new role of the Arabidopsis SEPALLATA3 gene revealed by its constitutive expression. Plant J. 43 586–596. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelmitsky I., Azizbekova N., Khayat E., Zieslin N. (2002). Morphological development of normal and phyllody expressing Rosa hybrida cv. Motrea flowers. J. Plant Growth Regul. 37 215–221. 10.1023/A:1020819123385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coen E. S., Meyerowitz E. M. (1991). The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature 353 31–37. 10.1038/353031a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews G. N., Bowman J. L., Meyerowitz E. M. (1991). Negative regulation of the Arabidopsis homeotic gene AGAMOUS by the APETALA2 product. Cell 65 991–1002. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90551-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A., Carrere S., Raymond O., Pouvreau B., Cottret L., Roccia A., et al. (2012). Transcriptome database resource and gene expression atlas for the rose. BMC Genomics 13:638 10.1186/1471-2164-13-638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A., Raymond O., Maene M., Baudino S., Langlade N. B., Boltz V., et al. (2010). Tinkering with the C-function: a molecular frame for the selection of double flowers in cultivated roses. PLoS ONE 5:e9288 10.1371/journal.pone.0009288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A., Remay A., Raymond O., Balzergue S., Chauvet A., Maene M., et al. (2011). Genomic approach to study floral development genes in Rosa sp. PLoS ONE 6:e28455 10.1371/journal.pone.0028455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario S., Busscher J., Franken J., Gerats T., Vandenbussche M., Angenent G. C., et al. (2004). Ectopic expression of the petunia MADS box gene UNSHAVEN accelerates flowering and confers leaf-like characteristics to floral organs in a dominant-negative manner. Plant Cell 16 1490–1505. 10.1105/tpc.019679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimba K. D., Tolkin T. R., Sullivan A. M., Melzer R., Theißen G., Di Stilio V. S. (2012). Loss of deeply conserved C-class floral homeotic gene function and C-and E-class protein interaction in adouble-flowered ranunculid mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 2267–2275. 10.1073/pnas.1203686109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt E. E. (2014). Plant grafting: new mechanisms, evolutionary implications. Front. Plant Sci. 5:727 10.3389/fpls.2014.00727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golino D. A., Oldfield G. N., Gumpf D. (1989). Experimental hosts of the beet leaf hopper-transmitted virescence agent. Plant Dis. 73 850–854. 10.1094/PD-73-0850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goto N., Pharris R. P. (1999). Role of gibberellins in the development of floral organs of the gibberellin-deficient mutant ga1-1 of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Bot. 77 944–954. 10.1139/cjb-77-7-944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G., Haas B. J., Yassour M., Levin J. Z., Thompson D. A., Amit I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson-Brown C., Savidge B., Yanofsky M. F. (1994). Regulation of the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene APETALA1. Cell 76 131–143. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90178-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans K., Morel P., Vandenbussche M. (2012). MADS-box genes and floral development: the dark side. J. Exp. Bot. 63 5397–5404. 10.1093/jxb/ers233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer S., Hansen S., Bantin J., Brettschneider R., Kranz E., Lörz H., et al. (2001). The maize MADS box gene ZmMADS3 affects node number and spikelet development and is co-expressed with ZmMADS1 during flower development, in egg cells, and early embryogenesis. Plant Physiol. 127 33–45. 10.1104/pp.127.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino Y., Kitahara K., Hirai S., Matsumoto S. (2006). Structural and functional analysis of rose class B MADS-box genes ‘MASAKO BP, euB3 and B3’: paleo-type AP3 homologue ‘MASAKO B3’ association with petal development. Plant Sci. 170 778–785. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.11.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenhout S. A., Oshima K., Ammar E.-D., Kakizawa S., Kingdom H., Namba S. (2008). Phytoplasmas: bacteria that manipulate plants and insects. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9 403–423. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00472.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijser P., Klein J., Lonnig W. E., Meijer H., Saedler H., Sommer H. (1992). Bracteomania, an inflorescence anomaly, is caused by the loss of function of the MADS-box gene squamosa in Antirrhinum majus. EMBO J. 11 1239–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen S. E., Olszewski N. E. (1991). Characterization of the arrest in anther development associated with gibberellin deficiency of the gib-1 mutant of tomato. Plant Physiol. 97 409–414. 10.1104/pp.97.1.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jofuku K. D., den Boer B. G. W., Montagu M. V., Okamuro J. K. (1994). Control of Arabidopsis flower and seed development by the homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell 6 1211–1225. 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M., Tsuda S., Tanaka Y., Mayama T., Okuyama Y., Tsuchimoto S., et al. (2002). Role of petunia pMADS3 in determination of floralor-gan andmeristem identity, as revealed by its loss of function. Plant J. 32 115–127. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann K., Muiño J. M., Jauregui R., Airoldi C. A., Smaczniak C., Krajewski P., et al. (2009). Target genes of the MADS transcription factor SEPALLATA3: integration of developmental and hormonal pathways in the Arabidopsis flower. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000090 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara K., Hibino Y., Aida R., Matsumoto S. (2004). Ectopic expression of the rose AGAMOUS-like MADS-box genes ‘MASAKOC1 and D1’ causes similar homeotic transformation of sepal and petal in Arabidopsis and sepal in Torenia. Plant Sci. 166 1245–1252. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.12.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara K., Matsumoto S. (2000). Rose MADS-box genes ‘MASAKOC1 and D1’ homologous to class C floral identity genes. Plant Sci. 151 121–134. 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00206-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek B. A., Meyerowitz E. M. (1996). The Arabidopsis homeotic genes APETALA3 and PISTILLATA are sufficient to provide the B class organ identity function. Development 122 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan N. T., Hogan K., Long J. A. (2012). APETALA2 negatively regulates multiple floral organ identity genes in Arabidopsis by recruiting the co-repressor TOPLESS and the histone deacetylase HDA19. Development 139 4180–4190. 10.1242/dev.085407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krussman G. (1981). The Complete Book of Roses. Portland: Timber Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ku T. C., Robertson K. R. (2003). “Rosa (Rosaceae),” in Flora of China, eds Wu Z. Y., Raven P. H. (Beijing: Science Press; ), 339–380. [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie. Nat. Methods 9 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I. M., Hammond R. W., Davis R. E., Gundersen D. E. (1993). Universal amplification and analysis of pathogen 16S rDNA for classification and identification of mycoplasmalike organisms. Phytopathology 83 834–842. 10.1094/Phyto-83-834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Oh M., Park H., Lee I. (2008). SOC1 translocated to the nucleus by interaction with AGL24 directly regulates LEAFY. Plant J. 55 832–843. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. M. (1964). Roses of china and roses of Europe. Acta Hortic. Sin. 3 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N., Chen W., Fan T., Tian Y., Zhang S., Zeng D., et al. (2015). Low temperature-induced DNA hypermethylation attenuates expression of RhAG, an AGAMOUS homolog, and increases petal number in rose (Rosa hybrida). BMC Plant Biol. 15:237 10.1186/s12870-015-0623-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima K., Iwai R., Himeno M., Komatsu K., Kitazawa Y., Fujita N., et al. (2014). Recognition of floral homeotic MADS domain transcription factors by a phytoplasmal effector, phyllogen, induces phyllody. Plant J. 78 541–554. 10.1111/tpj.12495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima K., Kitazawa Y., Tomomitsu T., Yusa A., Neriya Y., Himeno M., et al. (2015). Degradation of class E MADS-domain transcription factors in Arabidopsis by a phytoplasmal effector, phyllogen. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e1042635 10.1080/15592324.2015.1042635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel M. A., Bowman J. L., Kempin S. A., Ma H., Meyerowitz E. M., Yanofsky M. F. (1992). Manipulation of flower structure in transgenic tobacco. Cell 71 133–143. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90272-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., Piola F., Chessel D., Jay M., Heizmann P. (2001). The domestication process of the Modern Rose: genetic structure and allelic composition of the rose complex. Theor. Appl. Genet. 102 398–404. 10.1007/s001220051660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy R. E., Caudwell A., Chang C. J., Chen T. A., Chen T. Y., Chiykowski M. T., et al. (1989). “Plant diseases associated with mycoplasmas,” in The Mycoplasmas, eds Whitcomb R. F., Tully J. G. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ), 546–640. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer V. G. (1966). Flower abnormality. Bot. Rev. 32 165–195. 10.1007/BF02858659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mibus H., Heckl D., Serek M. (2011). Cloning and characterization of three APETALA1/FRUITFULL-like genes in different flower types of Rosa × hybrida L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 30 272–285. 10.1007/s00344-010-9190-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumoto K., Hatano H., Hirabayashi C., Murai K., Takumi S. (2011). Characterization of wheat bell1-type homeobox genes in floral organs of alloplasmic lines with Aegilops crassa cytoplasm. BMC Plant Biol. 11:2 10.1186/1471-2229-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J., Suh S. S., Lee H., Choi K. R., Hong C. B., Paek N. C., et al. (2003). The SOC1 MADS-box gene integrates vernalization and gibberellin signals for flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 35 613–623. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor Y., Zieslin N. (1992). Phyllody malformation in flowers of Rosa × hybrida cv. Motrea: effects of rootstocks, flower position, growth regulators and season. J. Exp. Bot. 43 89–93. 10.1093/jxb/43.1.89 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B. (2008). Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5 621–628. 10.1038/nmeth.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa K. (1980). Cutting-grafts as a means to propagate greenhouse roses. Sci. Hortic. 13 191–199. 10.1016/0304-4238(80)90084-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ÓMaoiléidigh D. S., Wuest S. E., Rae L., Raganelli A., Ryan P. T., Kwasniewska K., et al. (2013). Control of reproductive floral organ identity specification in Arabidopsis by the C function regulator AGAMOUS. Plant Cell 25 2482–2503. 10.1105/tpc.113.113209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaz S., Ditta G. S., Baumann E., Wisman E., Yanofsky M. F. (2000). B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 405 200–203. 10.1038/35012103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A., Robinson-Beers K., Ray S., Baker S. C., Lang J. D., Preuss D., et al. (1994). Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene BELL (BEL1) controls ovule development through negative regulation of AGAMOUS gene (AG). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 5761–5765. 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruokolainen S., Ng Y. P., Albert V. A., Elomaa P., Teeri T. H. (2010). Large scale interaction analysis predicts that the Gerbera hybrida floral E function is provided both by general and specialized proteins. BMC Plant Biol. 10:129 10.1186/1471-2229-10-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruokolainen S., Ng Y. P., Albert V. A., Elomaa P., Teeri T. H. (2011). Over-expression of the Gerbera hybrida At-SOC1-like1 gene Gh-SOC1 leads to floral organ identity deterioration. Ann. Bot. 107 1491–1499. 10.1093/aob/mcr112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samach A., Onouchi H., Gold S. E., Ditta G. S., Schwarz-Sommer Z., Yanofsky M. F., et al. (2000). Distinct roles of CONSTANS target genes in reproductive development of Arabidopsis. Science 288 1613–1616. 10.1126/science.288.5471.1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P., Lin T., Grandellis C., Yu M., Hannapel D. J. (2014). The BEL1-like family of transcription factors in potato. J. Exp. Bot. 65 709–723. 10.1093/jxb/ert432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaczniak C., Immink R. G. H., Angenent G. C., Kaufmann K. (2012). Developmental and evolutionary diversity of plant MADS-domain factors: insights from recent studies. Development 139 3081–3098. 10.1242/dev.074674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smykal P., Gennen J., De Bodt S., Ranganath V., Melzer S. (2007). Flowering of strict photoperiodic Nicotiana varieties in non-inductive conditions by transgenic approaches. Plant Mol. Biol. 65 233–242. 10.1007/s11103-007-9211-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyndel M. S. (2003). “Viruses,” in the Encyclopedia of Rose Science, eds Roberts A. V., Debener T., Gudin S. (Oxford: Elsevier Academic Press; ), 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Tadege M., Sheldon C. C., Helliwell C. A., Upadhyaya N. M., Dennis E. S., Peacock W. J. (2003). Reciprocal control of flowering time by OsSOC1 in transgenic Arabidopsis and by FLC in transgenic rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 1 361–369. 10.1046/j.1467-7652.2003.00034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandre K., Albert V. A., Sundas A., Engstrom P. (1995). Conifer homologues to genes that control floral development in angiosperms. Plant Mol. Biol. 27 69–78. 10.1007/BF00019179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Ortiz G., Huq E., Quail P. H. (2003). The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell 15 1749–1770. 10.1105/tpc.013839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Feng Z., Wang X., Zhang X. (2010). DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26 136–138. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. M., Brill E. M. (2004). Eucalyptus grandis has at least two functional SOC1-like floral activator genes. Funct. Plant Biol. 31 225–234. 10.1071/FP03181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D., Meyerowitz E. M. (1994). The ABC of floral homeotic genes. Cell 78 203–209. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90291-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmer F., Bowman J. L., Davies B., Ferrándiz C., Fletcher J. C., Franks R. G., et al. (2014). Flower development: open questions and future directions. Methods Mol. Biol. 1110 103–124. 10.1007/978-1-4614-9408-9_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter K. U., Becker A., Munster T., Kim J. T., Saedler H., Theissen G. (1999). MADS-box genes reveal that gnetophytes are more closely related to conifers than to flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 7342–7347. 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest S. E., ÓMaoiléidigh D. S., Rae L., Kwasniewska K., Raganelli A., Hanczaryk K., et al. (2012). Molecular basis for the specification of floral organs by APETALA3 and PISTILLATA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 13452–13457. 10.1073/pnas.1207075109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie A. P. (1954). The history of garden roses. J. R. Hortic. Soc. 79 555–571. [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. J., Zhang H., Chen M., Jian H. J., Baudino S., Caissard J. C., et al. (2014). De novo transcriptome analysis and identification of scent-related genes from Rosa chinensis ‘Pallida.’ Gene 540 96–105. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. J., Zhang H., Wang Q. G., Jian H. Y., Xiu X. Q., Wang J. H., et al. (2011). Isolation and identification of a putative scent-related gene RhMYB1 from rose. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38 4475–4482. 10.1007/s11033-010-0577-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky M. F., Ma H., Bowman J. L., Drews G. N., Feldmann K. A., Meyerowitz E. M. (1990). The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature 346 35–39. 10.1038/346035a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. Y., Zheng K. Y., Dong J. H., Fang Q., Wu S. P., Wang L. S., et al. (2014). Identification of a new tospovirus causing necrotic ringspot on tomato in China. Virol. J. 11:213 10.1186/s12985-014-0213-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. S., Zhu X. Z. (2006). China Rose. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 | Electron-microscopic analysis of sap extracts from young buds at stage 8–10 mm of R. chinensis cv. Viridiflora (A) and Old Blush used as negative control (B). The samples were negatively stained and analyzed at a magnification of ×100 000. The bar represents 100 nm. No trace of mycoplasma is observed in Viridiflora or Old Blush samples.

FIGURE S2 | No trace of MLO DNA is found in Viridiflora and Old Blush: DNA was prepared from buds at stage 8–10 mm of R. chinensis Viridiflora and Old Blush and then used to PCR amplify MLO DNA. M, molecular marker; C, positive control using MLO plasmid; 1,Viridiflora DNA; 2,Old Blush DNA.

TABLE S1 | Primers used for real-time quantitative PCR.

DATA SHEET S1 | The sequences of genes used for qRT-PCR validation.