Abstract

Background

Despite improved treatment options, heart failure remains the third most common cause of death in Germany and the most common reason for hospitalization. The treatment recommendations contained in the relevant guidelines have been incompletely applied in practice. The goal of this systematic review is to study the efficacy of adherence-promoting interventions for patients with heart failure with respect to the taking of medications, the implementation of recommended lifestyle changes, and the improvement in clinical endpoints.

Methods

We performed a meta-analysis of pertinent publications retrieved by a systematic literature search.

Results

55 randomized controlled trials were identified, in which a wide variety of interventions were carried out on heterogeneous patient groups with varying definitions of adherence. These trials included a total of 15 016 patients with heart failure who were cared for as either inpatients or outpatients. The efficacy of interventions to promote adherence to drug treatment was studied in 24 trials; these trials documented improved adherence in 10% of the patients overall (95% confidence interval [CI]: [5; 15]). The efficacy of interventions to promote adherence to lifestyle recommendations was studied in 42 trials; improved adherence was found in 31 trials. Improved adherence to at least one recommendation yielded a long-term absolute reduction in mortality of 2% (95% CI: [0; 4]) and a 10% reduction in the likelihood of hospitalization within 12 months of the start of the intervention (95% CI: [3; 17]).

Conclusion

Many effective interventions are available that can lead to sustained improvement in patient adherence and in clinical endpoints. Long-term success depends on patients’ assuming responsibility for their own health and can be achieved with the aid of coordinated measures such as patient education and regular follow-up contacts.

In spite of improved treatment options, heart failure is the third most common cause of death in Germany and constitutes the most common cause for inpatient admission to hospital (1). This disease burden has remained unchanged at this high level for patients and the healthcare system in spite of falling cardiovascular death rates (2– 5) and the successful development of medication treatments. The efficacy of these therapies has been shown in large multicenter studies across all stages and grades of severity of the disorder. This holds true for the introduction of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta receptor blockers, antiotensin-1 antagonists, and aldosterone antagonists (6– 10).

The prognosis for patients can additionally be improved effectively by disorder-specific lifestyle modifications and optimized self-care. These measures include, among others:

Monitoring for fluid retention by means of regular control of body weight and checking for leg edema (11, 12)

Independent adjustment of the medication according to agreed schemes

Putting dietary recommendations into practice (13).

These therapeutic recommendations have found their way into the current guidelines regarding healthcare provision for patients with heart failure (14– 16), but they are realized in patients’ everyday lives to an unsatisfactory degree. In this setting, the term adherence describes the extent to which a patient’s behavior with regard to medication intake or lifestyle changes is consistent with therapeutic recommendations (17). In contrast to the term compliance, which was used in the past, adherence implies a therapeutic alliance between doctor and patient, with joint decision making and support for self-care.

In recent years it has been shown repeatedly that in evidence-based and prognosis-relevant treatment measures, a clear interaction exists between adherence and the subsequent prognosis. In a recent cohort study, non-adherent patients accounted for 22.1% of all hospital admissions for clinically manifest heart failure, and they had a markedly shorter time interval until readmission to hospital (hazard ratio [HR] 0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI]: [0.25; 0.52]) (18). It is well known that low adherence to antihypertensive treatment notably increases the risk for clinically manifest heart failure (19).

On the background of the great prognostic importance of limited adherence in chronic heart failure, this systematic review aims to answer the following questions:

Is it possible to support patients with heart failure and to improve their adherence to medication therapy and lifestyle modifications in a sustained fashion?

Is improved adherence on the patients’ part associated with improved clinical outcomes, such as lower mortality, fewer inpatient stays in hospital, and improved quality of life?

Methods

This systematic review aims to summarize all randomized intervention studies of the improvement of adherence in patients with heart failure. The Box shows the inclusion criteria.

Box. Inclusion criteria.

-

Population

Patients with heart failure

-

Intervention

Strategies to improve patients’ adherence to taking their medication and self care

Training/education for patients

Reminder systems for patients

Measures to improve self care

Doctor oriented strategies

Organizational changes

Technical solutions

-

Control group

Standard care or other (less intensive) implementation strategy

-

Endpoint

Patients’ adherence after a minimum of 3 months’ follow-up to

Regular medication intake (for example, of ACE inhibitors or AT1 antagonists, beta-blockers, diuretics)

Symptom and weight control to detect fluid retention early

Low-salt diet

Restricted fluid intake

Support for/promotion of moderate physical activity

Avoidance of risk factors (for example, smoking)

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AT, angiotensin

Literature search

The study was conducted on the basis of the registered (reg No CRD42014009477) and published study protocol (20). The results were reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (21). We searched the databases Medline (Ovid), EMBASE, CENTRAL, PsycInfo, and CINAHL in July 2014 for all suitable studies that had been published since 2000 in English or German. In addition, we manually searched the reference lists of the included studies and systematic reviews.

Study selection and data extraction

The authors SU, FS, or SM checked—independently from one another—titles, summaries/abstracts, and potentially relevant full-text versions on the basis of the inclusion criteria. Information on patients’ adherence was described by using frequency data or scores on medication intake (eTable 1) and implementation of lifestyle modifications (eTable 2). In order to ensure that patients stuck to the interventions, a follow-up period of at least 3 months was a prerequisite for inclusion. Disagreements on the inclusion of studies were discussed with RP. Subsequently, the information set out in the study protocol was extracted by FS and SM and checked by MU. In addition to process parameters on adherence, we also collected data on patient-relevant result parameters, such as quality of life, mortality, and frequency and duration of hospital inpatient stays. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed on the basis of the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration (22).

eTable 1. Measurement of adherence to medications.

| Adherence to | Studies with maximal follow-up period (method) |

|---|---|

| Measurement over frequencies | |

| Prescribed medications |

6-9 Months: e1 (MEMS), e2 (self-reporting), e3 (MEMS), e4 (self-reporting), e5 (MEMS) ≥ 12 Months: e6, e7-e12 (self-reporting), e13 (tablet accountability method), e14 (self-reporting), e15 (MEMS) |

| Beta-Blockers |

3 Months: e3 (MEMS) ≥ 12 Months: e12, e14, e16, e17 (self-reporting) |

| ACE-inhibitors / ARB |

3 Months : e3 (MEMS) 6-9 Months: e18 (self-reporting) ≥ 12 Months: e12, e14, e16, e19 (self-reporting) |

| Diuretica / spironolactone |

3 Months: e3 (MEMS) ≥ 12 Months: e12 (self-reporting) |

| MRA | ≥ 12 Months: e14 (self-reporting) |

| Furoseminide | ≥ 12 Months: e12 (self-reporting) |

| Measurement over scores | |

| Prescribed medications |

3 Months:

e20, e21 (self-reporting) 6-9 Months: e22 (MARS) ≥ 12 Months: e23 and e24, e25 (Morisky-Score), e26 (selfreporting) |

MARS, medication adherence record scale; MEMS, medication event monitoring; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

eTable 2. Measurement of adherence to self-care management.

| Measurement tool | Studies with maximal follow-up period |

|---|---|

| Scores on multiple recommendations | |

| EHFScBS (13) and modifications* |

3 Months: e27*-e29*, e30* 6-9 Months: e31, e32, e33*, e34* ≥12 Months: e24, e35-e37, e38*, e39 |

| SCHFI (e42) and modifications* |

3 Months: e40*, e41, e42,, e43*, e44* 6-9 Months: e45*, e46*, e47 |

| Further scores, developed for studies |

3 Months:

e6*e20, e28, e48 6-9 Months: e26, e47, e49 ≥12 Months: e25, e50* |

| Self-efficacy |

3 Months: e20, e30, e51 6-9 Months: e4 ≥12 Months: e15, e52 |

| Single recommendations | |

| Daily weight and symptom control |

3 Months: e21, e27, e53 6-9 Months: e54 ≥12 Months: e10, e23; e52, e55 |

| Restrictions to sodium intake |

3 Months: e6, e20, e21, e56 6-9 Months: e2,e26, e57 ≥12 Months: e10, e12, e15, e23 |

| Restrictions to fluid intake |

3 Months:

e6, e21, e56 ≥12 Months: e23 |

| Exercise adherence |

3 Months:e6, e20 ≥12 Months: e10, e23 |

| Smoking cessation adherence |

3 Months:e20 ≥12 Months: e23 |

EHFScBS, European Heart Failure Self Care Behaviour Scale; SCHFI, Self-Care of Heart Failure

Index

Effect sizes

We calculated the effect size by comparing the frequencies of adherent behavior in the intervention and control groups. Furthermore, we calculated risk differences (RD) and numbers needed to treat (NNT). For metrically captured adherence we determined standardized mean differences (SMD). Positive differences describe improved adherence in the intervention group. The SMD allows for comparability of adherence, which was quantified by using several scores (23) and also shows the extent of the standard deviations by which each score was improved by applying the strategies. The treatment effects in the individual studies were summarized by using the random effects model, and the risk of publication bias was investigated by using a funnel plot.

Results

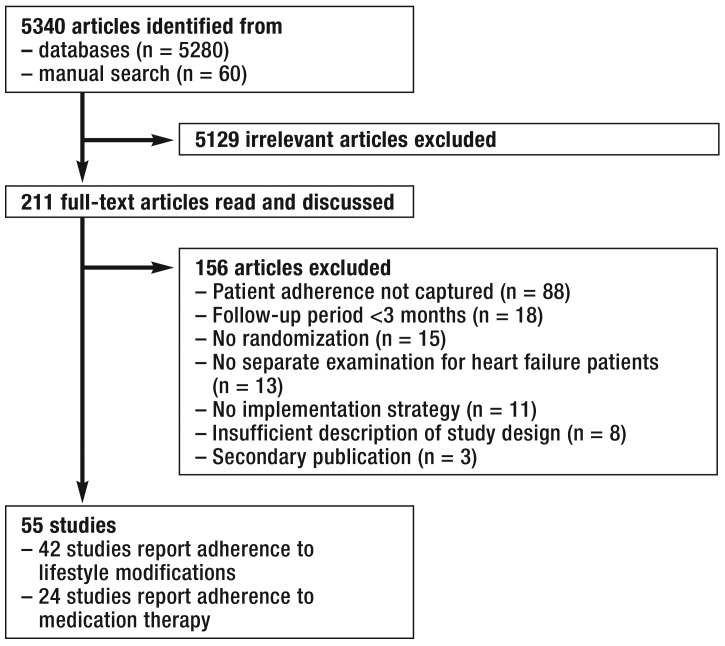

The systematic search identified 5340 potentially relevant articles. After checking titles and abstracts and reading 211 full text articles, we included 55 studies in our review. Altogether 24 studies reported on adherence to medication therapy and 42 studies on lifestyle modifications; 11 studies reported on both subjects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

How the literature search was undertaken

Description of included studies

The 55 studies that were included in this review had been conducted in 17 countries on four continents and investigated the efficacy of adherence-improving measures in a total of 15 016 patients with heart failure. All studies had used a randomized design; as a rule, randomization took place at the level of the patients and in two studies at the level of doctors’ practices.

Patients

Patients were recruited after an acute event in hospital in 39 studies; in 16 studies, they were recruited in a stable condition in the outpatient setting. 62% of study participants were men; three studies included men only. The mean age ranged between 51 years and 78 years. Patients were affected by different limitations in terms of physical resilience and comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, fat metabolism disorders, chronic renal failure, or depression. Individual studies excluded patients with severe psychological or cognitive impairments (15 studies), and others excluded patients with renal failure (11 studies).

Interventions

In most studies, several types of intervention were combined so as to improve adherence by various means—and thus a patient’s prognosis.

Training/education sessions for patients—All studies described training measures for patients on the following topics: disease course and how to deal with the disorder, necessary therapeutic steps, early detection of deteriorating symptoms, and necessary lifestyle modifications. The training sessions were provided on the basis of individual treatment plans by nursing staff or pharmacists and were complemented by lectures, discussion services, brochures, newsletters, computer programs, or other learning materials—interactive ones, in some cases.

Patient reminder systems (22 studies)—These were based on regular telephone calls or home visits by specialized nursing staff, doctors’ assistants, or pharmacists. Details of disease symptoms and adherence were recorded and discussed.

Support for self-care (32 studies)—This included all measures that enabled patients to better deal with their disorder, such as: independent use of measuring instruments, keeping a heart failure diary, schemes for diuretic adjustment, pill organizers, medication lists, or an advisory hotline.

Doctor-oriented interventions (11 studies)—In these, optimized or simplified therapeutic plans and suggestions for how to support patients were developed by pharmacists, nursing staff, or practice assistants; these were made available to treating physicians.

Organizational change (21 studies)—These concerned a restructuring of the tasks involved in caring for the patient during an inpatient stay and after discharge, between primary care physicians, cardiologists, psychologists, pharmacists, and nursing staff. Clinical investigations were undertaken—often by nursing staff—for the purpose of symptom monitoring and advice given on lifestyle modifications and diuretic adjustment.

Telemonitoring systems (13 studies)—These enabled measuring weight, blood pressure, heart rate, and automated prompting for adherence, symptoms, and awareness of medication therapy and lifestyle modifications, as well as direct control by nursing staff/specialized teams.

Potential biases

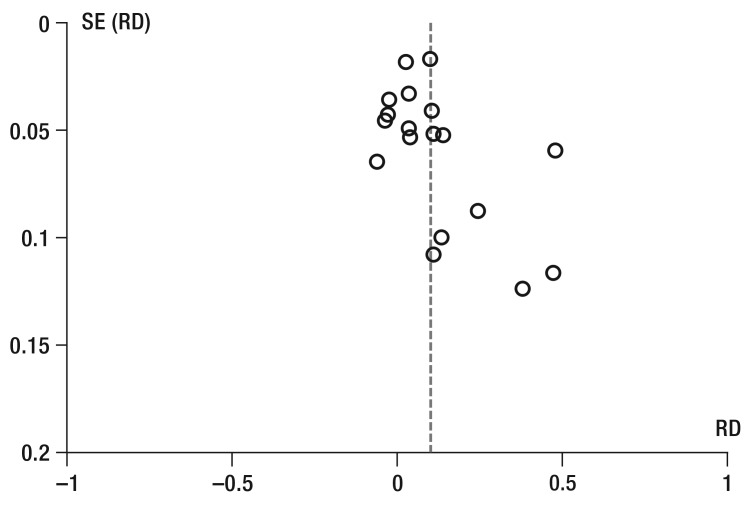

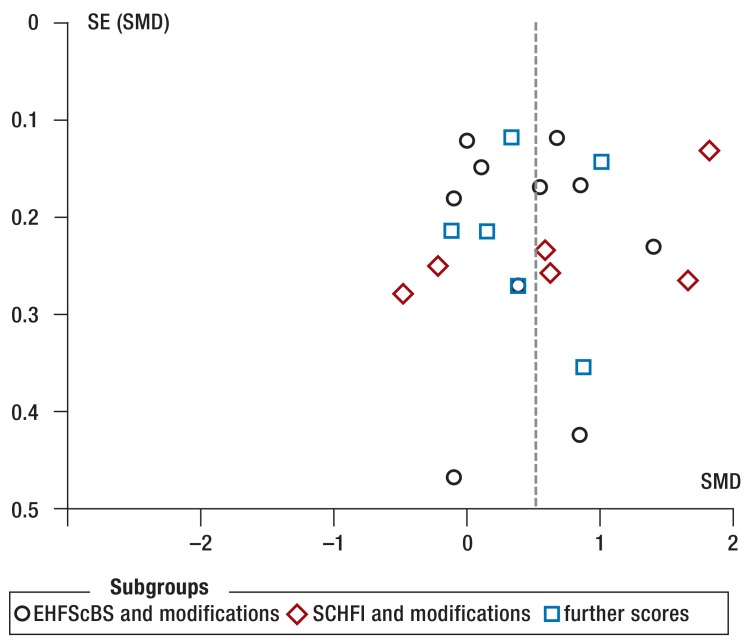

The greatest restriction to study quality was unblinded self-reported adherence with a potentially high risk of bias in the direction of “desired behavior” (36 studies). Problems in generating randomization or blinded allocation could not be excluded in 23 and 39 studies, respectively. Further limitations resulted from the high rates of dropouts and from per-protocol analyses, which may bias effect sizes (19 studies), deviations between planned and reported endpoints (9 studies), and relevant differences between the intervention groups at the start of the study (14 studies). Publication bias cannot be excluded because negative treatment effects on adherence were rarely reported (eFigure 1, eFigure 2).

eFigure 1.

SE (RD)

Funnel plot for intervention effects on adherence to medication therapies.

SE, standard error; RD, risk difference

eFigure 2.

Funnel plot for intervention effects on adherence to lifestyle recommendations.

EHFScBS, European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale; SCHFI, self care heart failure index; SE, standard error; SMD, standardized mean difference

Efficacy of the interventions

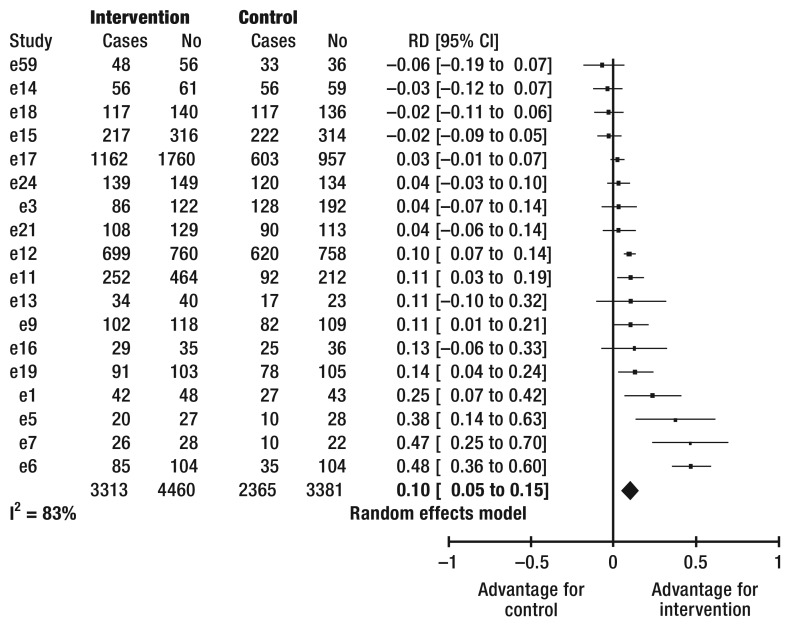

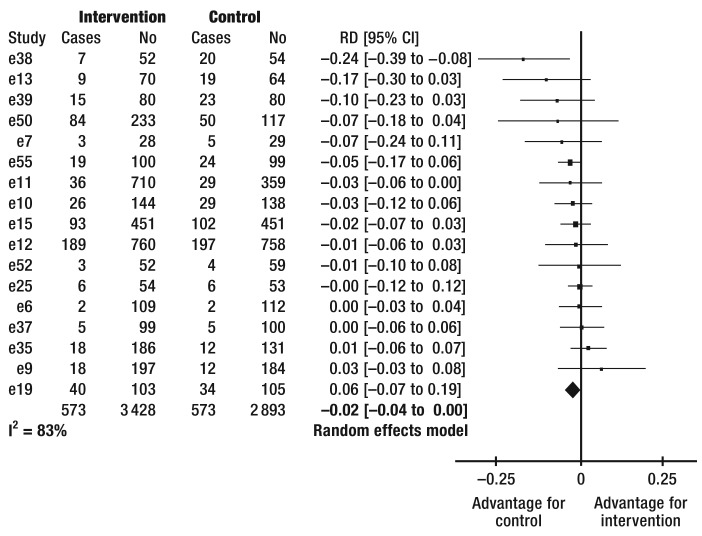

Adherence to medication treatment—This was tested in 24 studies (eTable 1). Combining the treatment effects from 18 studies shows improved adherence in 10% (95% CI [5; 15]) (Figure 2) of patients by means of the intervention under study (number needed to treat [NNT] 10; 95% CI [7; 20]). It was not possible to calculate risk differences for six studies (e2, e10, e20, e22, e25, e26). None of these studies found improved adherence to medication intake.

Figure 2.

Forest plot

of the efficacy of interventions on the frequency of patients’ adherence to medication therapy. I2, heterogeneity

CI, confidence interval

No, number of patients

RD, risk difference

Adherence to lifestyle recommendations—This was investigated in a total of 42 studies and improved in 31 studies (eTable 2). The pooled effects of 22 studies in which adherence was calculated by using different summative scores (24, 25), showed improved adherence in the intervention groups in 12 studies (Table). Improved adherence regarding individual recommendations was reported in 15 out of 18 further studies, with some studies reporting summative scores as well as adherence to individual recommendations. Five studies reported adherence by using different scores for which it was not possible to calculate any differences (e25, e28, e39, e44, e49). In four of these studies, adherence improved successfully.

Table. Studies of the efficacy of interventions on patients’ adherence to lifestyle modifications.

| A) EHFscBS and modifications | |||||||

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Study | Mean | SD | No | Mean | SD | No | SMD [95% CI] |

| e36 | 0.6 | 8.2 | 57 | 1.3 | 6.9 | 63 | −0.09 [−0.45 to 0.27] |

| e27 | 106 | 21 | 9 | 108 | 22 | 9 | −0.09 [−1.01 to 0.84] |

| e35 | 49.2 | 6.3 | 156 | 49.2 | 6.6 | 109 | 0.00 [−0.24 to 0.24] |

| e33 | 10.4 | 3.1 | 84 | 10.1 | 2.9 | 95 | 0.10 [−0.19 to 0.39] |

| e34 | 52.2 | 10.1 | 29 | 48.5 | 9 | 26 | 0.38 [-0.15 to 0.91] |

| e37 | −21.2 | 6.4 | 65 | −24.8 | 6.7 | 78 | 0.55 [0.21 to 0.88] |

| e24 | −17.4 | 4.5 | 149 | −20.8 | 5.8 | 134 | 0.66 [0.42 to 0.90] |

| e29 | 2.9 | 1 | 14 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 11 | 0.85 [0.02 to 1.68] |

| e31 | 12.1 | 10.9 | 76 | 3.1 | 10 | 75 | 0.86 [0.52 to 1.19] |

| e30 | −27.1 | 2.5 | 47 | −30.1 | 1.7 | 46 | 1.39 [0.93 to 1.84] |

| I² = 83% Random effects model | 686 | 646 | 0.41 [0.30 to 0.52] | ||||

| B] SCHFI and modifications | |||||||

| e42 | 159.2 | 46.3 | 27 | 178.4 | 29.6 | 26 | −0.48 [−1.03 to 0.06] |

| e47 | 65.1 | 22.7 | 30 | 70 | 19.2 | 34 | −0.23 [−0.72 to 0.26] |

| e40 | 2.6 | 0.67 | 37 | 2.2 | 0.67 | 39 | 0.59 [0.13 to 1.05] |

| e43 | 19.6 | 2.1 | 34 | 18 | 2.9 | 29 | 0.63 [0.12 to 1.14] |

| e38 | 12.4 | 1 | 45 | 10.8 | 0.9 | 34 | 1.65 [1.14 to 2.17] |

| e50 | 51.8 | 5.8 | 233 | 39.9 | 7.9 | 117 | 1.81 [1.55 to 2.07] |

| I² = 95% Random effects model | 406 | 279 | 1.03 [0.86 to 1.20] | ||||

| C) Further scores | |||||||

| e59 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 56 | 6.2 | 2.5 | 36 | −0.12 [−0.54 to 0.30] |

| e48 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 40 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 47 | 0.15 [−0.27 to 0.57] |

| e24 | 54.9 | 6.5 | 149 | 52.3 | 8.9 | 134 | 0.34 [0.10 to 0.57] |

| e34 | 52.2 | 10.1 | 29 | 48.5 | 9 | 26 | 0.38 [−0.15 to 0.91] |

| e20 | 50.6 | 4.7 | 18 | 46.5 | 4.5 | 17 | 0.87 [0.17 to 1.57] |

| e51 | 35.9 | 2.73 | 108 | 32.74 | 3.53 | 108 | 1.00 [0.71 to 1.28] |

| I² = 81% Random effects model | 400 | 368 | 0.46 [0.31 to 0.60] | ||||

EHFScBS, European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale; I², heterogeneity; CI, confidence interval; No, number of patients per group; SCHFI, self care heart failure index; SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference (positive differences describe an advantage for the intervention)

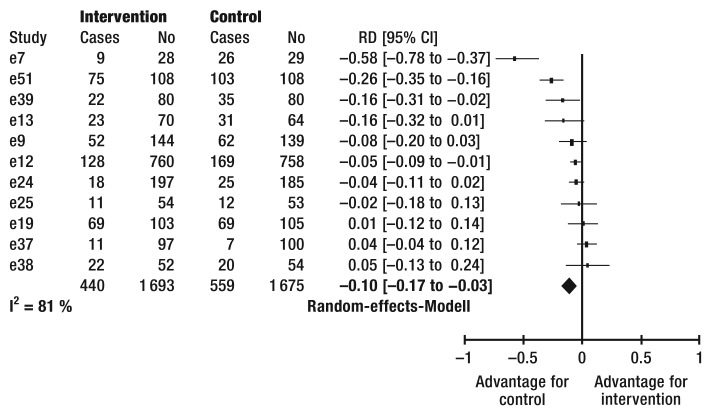

Association between adherence and clinical parameters—44 studies had collected data on the efficacy of the interventions on clinical parameters (mortality, admission to hospital or quality of life). Improved adherence to medication therapy or lifestyle recommendations resulted in 6 and 11 studies, respectively, in significant improvements of at least one clinical endpoint (eTable 3, eTable 4). Improved adherence to at least one of the studied recommendations resulted in the long term in an absolute reduction in mortality of 2 percentage points (95% CI [0; 4]) (17 studies including 6321 patients; eFigure 3) and a 10 percent reduction in the proportion of patients requiring inpatient stays (95% CI [3; 17]) (11 studies including 3368 patients; eFigure 4) within 12 months after the start of the intervention. Only one study investigated and confirmed an association between improved adherence to lifestyle interventions (keeping a heart failure diary) and lower mortality (e55). eTable 5 summarizes all studies that did not find any improvement in clinical endpoints.

eTabelle 3. Studies with improved adherence to medications and improved clinical outcomes in the intervention group.

| Article | Study type recruit ment | Population number, age, male, NYHA (I/II/III/IV), comorbidities | Comparison Intervention (IG) vs. control (CG) | Risk of bias (I/II/III/IV /V/VI) | Patient adherence (measurement, followup) IG vs. CG | Conclusions on primary outcome, clinical outcomes and adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonicelli 2010 (e7) |

RCT Italy 16 months |

57 hospitalized HF patients 78±7 years, 61% male NYHA: 0/58/37/5% Exclusion of patients with severe dementia, debilitating psychiatric disorders or chronic renal failure requiring dialysis |

IG (n=28):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Adherence to prescribed treatment: 12-months: 89.7 vs. 35.7% | Intervention can improve the composite endpoint of mortality and hospitalization and medication adherence (RD 0.47; 95%CI 0.25 to 0.70), but not mortality and quality of life. |

| Brotons 2009 (e9) |

RCT Spain 01/2004 to 09/2005 |

283 hospitalized HF patients 76±8 years, 45% male NYHA 49/45/5/1% Diabetes: 42% Hypertension: 76% Exclusion of patients with a cognitive deficit |

IG (n=144):

|

low/ low/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Adherence to pharmacological treatment (high scores are better) 12-months: 86.1 vs. 75.5%. |

Intervention can reduce mortality and hospital readmissions, improve QoL and medication adherence (RD 0.11; 95%CI 0.01 to 0.21). |

| Galbreath

2004 (e11) |

RCT USA 1999 to 2003 |

1069 patients with HF

symptoms identified

through lists from

partner institutions 71±10 years, 71% male NYHA: 19/57/21/3% Diabetes: 28% Hypertension: 72% Hyperlipidemia: 50% |

IG (n=710):

|

unclear/ unclear/ unclear/ unclear/ low/ low |

Adherence to guideline-based medications in systolic HF patients 18-months: 54.4 vs. 43.3% |

Intervention can decrease mortality, but not event-free survival and improve longtime medication adherence (RD 0.11; 95%CI 0.03 to 0.19). - |

| GESICA 2005 (e12) |

RCT Argentin a 06/2000 to 11/2001 |

1518 ambulatory stable HF patients 65±13 years, 71% male NYHA III-IV: 49% Diabetes: 21% Hypertension:59% Exclusion of patients with primary pulmonary hypertension |

IG (n=760):

|

low/ low/ unclear/ low/ high/ low |

Adherence to medication and diet (mean follow-up of 16 months): beta-blocker: 59 vs. 52% spironolactone: 27 vs. 23% digoxin: 33 vs. 29% furosemide: 77 vs. 70% ACE-inhibitors: 78 vs.6% Drug stop: 8 vs. 18%. dietary transgressions: 20 vs. 65% |

Intervention can decrease mortality, readmissions and the probability of worsening HF and improve QoL and medication adherence (no drug stops of any drugs: RD 0.10; 95%CI 0.07 to 0.14 and diet: RD 0.45; 95%CI 0.40 to 0.49). |

| Sadik 2005 (e6) |

RCT United Arab Emirate s |

221 HF patients from general medical wards and from cardiology and medical outpatient clinics 59 years, 50% male NYHA: 30/50/16/4% Diabetes: 18% Hypertension: 23% Exclusion of patients with low cognitive status |

IG (n=109):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Compliance with the

prescribed medicines:

12-months: 82 vs. 34% Lifestyle advice: baseline: 21 vs. 22% 12-months: 72 vs. 28% |

Intervention can improve QoL and compliance to medications (RD 0.48; 95%CI 0.36 to 0.60) and lifestyle adjustments (RD 0.44; 95%CI 0.32 to 0.56) with no influence on mortality. |

| Wu 2012 (e5) |

RCT USA |

82 HF ambulatory and

hospitalized patients 60±13 years, 57% male NYHA I-II/III-IV: 51/49% Charlson comorbidity index: 3.1±1.9 Exclusion of patients with impaired cognition |

IG (n=54):

|

unclear/

unclear/ low/ unclear/ low/ high |

Medication taking adherence: baseline: 70 vs. 59 vs. 64% 9-months: 74 vs. 65 vs. 36% |

Intervention improved eventfree survival, hospitalization, but not mortality and QoL. Intervention can improve adherence in both intervention groups (RD 0.38; 95%CI 0.14 to 0.63 and RD 0.29; 95%CI 0.03 to 0.54). |

CG, Control group; CI, confidence interval; DM, disease management; HF, heart failure; IG, intervention group; n, number of randomized participants; NYHA, New York

Heart Association; QoL, Quality of life; RD, risk difference; RCT, randomized control trial;

RD>0 describe better adherence in IG

Risk of bias: I, random sequence generation; II, allocation concealment, III, blinding of outcome assessment; IV, incomplete outcome data; V: selective reporting; VI: otherbias

eTabelle 4. Studies with improved adherence to self-care management and improved clinical outcomes in the intervention group.

| Article | Study type recruit ment | Population number, age, male, NYHA (I/II/III/IV), comorbidities | Comparison Intervention (IG) vs. control (CG) | Risk of bias (I/II/III/IV /V/VI) | Patient adherence (measurement, follow-up) IG vs. CG | Conclusions on primary outcome, clinical outcomes and patient’s adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benatar 2003 (e51) |

RCT USA 04/1997 to 07/2000 |

216 hospitalized CHF patients 63±13 years, 37% male NYHA III or IV Diabetes: 23% Hypertension: 94% Exclusion of patients with renal failure or severe dementia or another debilitating psychiatric disorder |

IG (n=108):

CG (n=108):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Self-efficacy (higher scores are better): baseline: 32.0±3.1 vs. 31.0±4.5 3-months: 35.9±2.7 vs. 32.7±3.5 |

Intervention can decrease HF readmissions, length of hospital stay, costs and improve QoL and self-efficacy (MD 3.16; 95%CI 2.32 to 4.00). |

| Bocchi 2008 (e50) |

RCT Brasilia 10/1999 to 01/2005 |

350 ambulatory CHF patients 51±17 years, 69% male NYHA 21/40/27/12% Diabetes: 17% Exclusion of patients with severe renal diseae |

IG (n=223):

|

low/ low/ low/ low/ low/ low |

Adherence (higher scores are better): baseline: 30.8 ±11 vs. 36.4 ±9.9 up to 6 (mean 2.5±1.7) years: 51.8 ±5.8 vs. 39.9 ±7.9 |

Intervention can reduce unplanned hospitalization, hospital days, emergency care, mortality and improve QoL and self-care-adherence (MD 11.9; 95%CI 10.3 to 13.5). |

| Brandon 2009 (e28) |

RCT USA |

20 HF patients 60 (49 to 69) years, 45% male NYHA 25/50/20/5% |

IG (n=10):

|

unclear/ unclear/ unclear/ low/ unclear/ high |

Self-care over the last 3 months (higher scores are better): Baseline: 95.9 vs. 94 6-months (3-months after the intervention): 128 vs. 94 (p<0.001). |

Intervention can decrease hospital admissions and improve QoL and self-care behavior (MD 34). |

| Dansky 2009 (e54) |

RCT USA started in 01/2006 |

108 CHF patients, discharged from Medicare-certified homehealth agencies 78 (22-98) years |

Use of a telehealth-based disease management system in the hospital IG (n=64):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ high/ unclear/ high |

Self-management (weight control): 6-months: 86.7% vs. 50% |

Intervention can decrease hospitalizations and emergency department visits and improve QoL. It can increase the frequency of patients who measured daily their weight (RD 0.37; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.57) |

| DeWalt 2006 (e52) |

RCT USA 11/2001 to 04/2003 |

127 HF patients from the General Internal Medicine and Cardiology Practices at a university hospital 62±10 years, 49% male NYHA: 0/50/46/4 Diabetes: 55% Hypertension: 88% Exclusion of patients with dementia or on dialysis |

IG (n=62):

|

low/ low/ high/ low/ low/ high |

HF self-efficacy (higher scores are better): 12 months: MD 2 (95%CI 0.7 to 3.1) Daily weighting: 79 vs. 29%. |

Intervention can decrease hospitalization or deaths with no influence on mortality and QoL. It can improve selfefficacy and the frequency of daily weighting (RD 0.50; 95%CI 0.34 to 0.66). |

| Kasper 2002 (e2) |

RCT USA 12/1996 to 12/1998 |

200 hospitalized CHF patients at high risk of hospital readmission 62±14 years, 60% male NYHA II/III: 36/58% Diabetes: 40% Hypertension: 67% Exclusion of patients with psychiatric disease or dementia |

IG (n=102):

CG (n=98):

|

low/ low/ high/ low/ low /low |

Good or average compliance with dietary recommendations: 6-months: 69 vs. 45%, Medication compliance: no differences (not shown) | Intervention might reduce readmissions and mortality. It can improve QoL and compliance to dietary recommendations RD 0.24; 95%CI 0.10 to 0.39), but did not influence medication compliance. - |

| Korajkic 2011 (e53) |

RCT Australia 02/2008 to 10/2008 |

70 HF patients presenting at a referral outpatient clinic 57±12 years, 77% male NYHA: 0/72/27/1% Diabetes: 16% Hypertension: 44% Hypercholesterinaemia: 51% Exclusion of patients with baseline renal impairement (serum creatinine concentration > 200 μmol/L or on dialysis), severe psychiatric illness or moderate to severe dementia |

IG (n=35):

CG (n=35):

|

low/ unclear/ low/ low/ low/ low |

patients with appropriate weight-titrated furosemide dose adjustments: 3-months: 80% vs. 51% |

The intervention can improve the ability of HF patients to self-adjust their diuretic dose by a flexible dosing regime (RD 0.29; 95% CI 0.07-0.50) and might reduce readmissions and QoL. |

| Shao 2013 (e30) |

RCT Taiwan 10/2006 to 01/2007 |

108 hospitalized CHF patients 72±6 years, 68% male NYHA: 7/66/27/0% number of co-morbidities: 3.8±0.8 Exclusion of patients with renal failure or debilitating psychiatric disorder |

IG (n=54):

|

low/ low/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Self-efficacy for salt and fluid control (higher scores are better): baseline: 41.6±10.2 vs. 43.6±10.3 3-months: 50.8±5.4 vs. 42.9±8.1 Self-care (modified EHFscBS): baseline: 29.2±3.7 vs. 29.2±3.3 3-months: 27.1±2.5 vs. 30.1±1.7 |

Intervention can improve selfefficacy for salt and fluid control (MD 7.9; 95%CI 5.1 to 10.7), self-care (MD 3.0; 95%CI 2.1 to 3.9) and HFrelated symptoms. |

| Strömberg 2003 (e380) |

RCT Sweden 06/1997 to 12/1999 |

106 hospitalized HF patients 78±7 years, 61 % male NYHA: 0/18/71/11% Diabetes: 24% Hypertension: 40% Exclusion of patients with dementia or other psychiatric illness |

IG (n=52):

|

low/ low/ high/ high/ low/ high |

Self-care change from baseline to 12 months follow-up (higher scores are better): 2.3 vs. 0.5 (p=0.01) | - Follow-up in a nurseled HF clinic can improve survival, reduce hospital admissions and improve selfcare (MD 1.6; 95%CI 1.2 to 2.0). |

| Wierzcho wiecki 2006 (e39) |

RCT Poland |

160 hospitalized CHF patients 68±10 years, 59% male NYHA: 0/14/47/39% Diabetes: 28% Hypertension: 48% |

IG (n=80):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ unclear/ low/ high |

Self-care (EHFscBS): 12-months (lower scores are better): 19.5 (IQR 16 to 24) vs. 42 (IQR 37 to 47) (p<0.001) |

Intervention can decrease the frequency of readmissions, length of hospital stay, mortality, improve QoL and self-care (MD 22.2). |

| Wright 2003 (e55, e60) |

RCT New Zealand 1996 to 1997 |

197 hospitalized HF patients due to first diagnosis or exacerbation 73±11 years, 60% male NYHA I-II/III : 93/7% Diabetes: 29% Treated hypertension: 52% |

IG (n=100):

CG (n=97):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Self-weighting: 12 months: 87 vs. 29% |

Intervention had no influence on the combined endpoint of hospital readmission and death despite improved QoL and slightly lower mortality. It increased number of patients who used self-weighting (RD 0.29; 95%CI 0.03 to 0.54). |

CG, Control group; CI, confidence interval; DM, disease management; EHFscBS, European Heart Failure Self-care behavior scale; HF, heart failure; IG, intervention group; IQR: inter-quartile-range; n, number of randomized participants; MD: mean difference; NYHA, New York Heart Association; QoL, Quality of life; RD, risk difference; RCT, randomized control trial;

MD, RD>0 describe better adherence in IG

Risk of bias: I, random sequence generation; II, allocation concealment, III, blinding of outcome assessment; IV, incomplete outcome data; V: selective reporting; VI: other bias

eFigure 3.

Forest plot of the efficacy of interventions with improved adherence on mortality within 12 months.

I2, heterogeneity

CI, confidence interval

No, number of patients

RD, risk difference

eFigure 4.

Forest plot of the efficacy of interventions with improved adherence on frequency of hospital inpatient admissions within 12 months.

I2, heterogeneity

CI, confidence

interval

No, number of

patients

RD, risk difference

eTabelle 5. Studies with no improvement of adherence and clinical outcomes in the intervention group.

| Article | Study type recruit ment |

Population number, age, male, NYHA (I/II/III/IV), comorbidities |

Comparison Intervention (IG) vs. control (CG) |

Risk of bias (I/II/III/IV/ V/VI) |

Patient adherence (measurement, follow-up) IG vs. CG | Conclusions on primary outcome, clinical outcomes and patient’s adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agren 2010 (e36) |

RCT Sweden 01/2005 to 12/2008 |

155 recently discharged HF patients after a acute exacerbation 71±11 years, 75% male NYHA: /32/53/15% Diabetes: 12% Hypertension: 34% Exclusion of patients with dementia or severe psychiatric illnesses |

IG (n=84):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ high |

Self-care (EHFscBS) change to baseline: 3-months: 3.1 ± 6.3 vs. 2.0 ± 6,9 12-months: 0.6 ± 8.2 vs. 1.3 ± 6.9 |

Intervention initially improved patients’ level of perceived control with no effect on long-term self-care (MD-0.70; 95%CI -2.03 to-3.43) and QoL. |

| Albert 2007 (e40) |

RCT USA 05/2000 to 07/2002 |

112 hospitalized HF patients after an acute decompensation 60±14 years, 77% male Diabetes: 33% Hypertension: 54% Hyperlipidemia: 46% Renal insufficiency: 34% Exclusion of mentally not alert patients |

IG (n=59):

|

high/ low/ high/ low/ unclear/ low |

Self-care (SCHFI): 3-months: 2.6 vs. 2.2 (p=0.01) |

Intervention did not influence healthcare utilization (including hospitalization) and the number of HFsymptoms, but it can improve self-care behavior (MD 0.4; 95%CI 0.1 to 0.7). |

| Arcand 2005 (e56) |

RCT Canada |

47 stable HF patients from an ambulatory HF clinic 58±3 years, 74% male Exclusion of patients with diabetes requiring insulin or severe renal dysfunction |

IG (n=23):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ unclear |

Sodium intake (g/d): baseline: 2.80±1.47 vs. 3.00±1.52 3-months: 2.14±1.13 vs. 2.74±1.68 fluid intake (1.88L/d): baseline: 1.86±0.54 vs. 2.26±1.01 3-months: 1.88±0.64 vs. 2.02±0.72 |

Intervention might reduce sodium and fluid intake (MD 0.60; 95%CI -0.22 to 1.42 and 0.14; 95%CI -0.25 to 0.53). |

| Artinian 2003 (e27) |

RCT USA |

18 scheduled HF patients 68±11 years, 94% male NYHA: 0/39/50/11% Exclusion of patients with dementia, mental illnesses or hemodialysis |

Educational booklet on HF self-care behavior IG (n=9):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ low/ high/ unclear |

Self-Care (revised SCB): baseline: 92±8 vs. 95±22 3-months: 106±21 vs. 108±22 compliance to daily weight monitoring: 3-months: 85 vs. 79% blood pressure monitoring: 3-months: 81 vs. 51% |

Intervention did not improve self-care behavior (MD -2; 95%CI -22 to 18) and might improve compliance to daily weighting (RD 0.08; 95%CI -0.30 to 0.45) and blood pressure monitoring with no influence on QoL. |

| Balk 2008 (e32) |

RCT Netherla nds 07/2005 to 08/2006 |

214 stable HF patients 66 (33-87) years, 70% male NYHA 7 /41/50/2% Diabetes: 31% Hypertension 33% |

IG (n=101):

|

unclear/ low/ high/ high/ high/ high |

Self-Care (EHFscBS): no differences at the end of the study (mean follow-up 288 days, data not reported) |

Intervention did not reduce mortality and the numbers of days in hospital and had no effect on QoL and selfcare behavior. |

| Barnason 2003 (e20) |

RCT USA |

35 ischemic hospitalized HF CABG patients 73±5 years, 69% male NYHA I to II |

IG (n=18):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ unclear/ unclear/ unclear |

Cardiovascular Risk Factor Modification Adherence (4=always adhere) at 3-months: exercise: 4.0±0.0 vs. 3.4±0.86 diet: 3.4±0.89 vs. 3.2±0.75 stress reduction: 4.0±0.0 vs. 3.3±0.77 medication use/ Tobacco cessation: 4.0±0.0 vs. 4.0±0.0 Summary score not reported self-efficacy (higher scores are better): baseline: 43.2±9.5 vs. 43±6.4 3-months: 50.6±4.7 vs. 6.5±4.5 |

Intervention can improve self-efficacy (MD 4.10; 95%CI 3.37 to 4.83) and some components of QoL compared with usual care with no influence on lifestyle and medication adherence. |

| Bouvy 2003 (e1) |

RCT Netherla nds 07/1998 to 02/2000 |

152 HF patients in a hospital or attending a HF outpatient clinic 70±11 years, 66% male NYHA 10/42/44/4% Diabetes: 28% Hypertension: 40% Renal Insufficiency: 13% Exclusion of patients with dementia or severe psychiatric problems |

IG (n=74):

|

low/ unclear/ low/ high/ low/ low |

Medication compliance over the time (>95% compliance): up to 6 months: 87% vs. 63% | Intervention can improve medication compliance (RD 0.25; 95%CI 0.07 to 0.42) with no influence on QoL, readmissions and mortality. |

| Bowles 2010 (e45) |

RCT USA |

218 hospitalized HF patients 72±10 years, 36% male 6.8±4 number of comorbidities Exclusion of mentally not competent patients |

IG:

|

unclear/ unclear/ low/ high/ high/ unclear |

Self-care (SCHFI): 6-months: maintenance: 57±4 to 72±19 management 48±26 to 64±24 |

Both groups improved self-care and reached adequate levels with no differences between groups. Intervention might reduce readmissions. |

| Boyne 2012 & 2014 e23, e24) |

RCT Netherla nds 10/2007 to 12/2008 |

382 scheduled HF patients 71±11 years, 59% male NYHA 0/57/40/3% Exclusion of patients with hemodialysis or (pre)dementia |

IG (n=187):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ low |

Self-care (EHFscBS): baseline: 18.9±5.3 vs. 20.9±6.1 12-months: 17.4±4.5 vs. 20.8±5.7 Self-efficacy: baseline: 53.2±7.1 vs. 51.1±9.6 12-months: 54.9±6.5 vs. 52.3±8.9 HF compliance scale at 12 months: medications: 93.5 vs. 89.8 weighting: 75.4 vs. 61.3 diet: 73.8 vs. 69.9 fluid: 76.5 vs.68.6 activities: 63.8 vs. 62.8 and appointments, smoking, alcohol |

Intervention can increase mean time to first HF-related hospitalization and decrease number of hospitalization with no effect on mortality, can improve self-care (MD 3.4; 95%CI -4.6 to -2.2) and might improve selfefficacy (MD 1.18; p=0.192) and HF compliance. |

| Caldwell 2005 (e29) |

RCT USA |

36 stable HF patients from a cardiology practice 71±15 years, 69% male NYHA I-IV Exclusion of patients with a neurological disorder that impaired cognition |

IG (n=20):

|

unclear/ unclear/ unclear/ low/ unclear/ high |

Self-care (abbreviated EHFscBS) baseline: 1.6±0.9 vs. 1.5 ±0.8 3-months: 2.9±1.0 (better) vs. 1.9±1.3 |

Intervention can improve knowledge and self-care behavior (MD 1.0; 95%CI 0.05 to 1.93). |

| Copeland 2010 (e10) |

RCT USA 06/2005 to 12/2005 |

458 HF hospitalized or frequently treated ambulant patients from the Veterans Health Administration (VA) 70±11 years, 100% male Diabetes: 54% Hypertension: 81% Exclusion of patients with severe dementia or on dialysis |

IG (n=220):

Usual care |

high/ unclear/ unclear/ high/ high/ low |

Compliance to selfcare at 12 months: check weight daily: OR 1.94; 95%CI 1.06 to 3.55 exercise: OR 1.94; 95%CI 1.08 to 3.49 recommended diet: OR 1.29; 95%CI 0.72 to 2.29 medications: OR 0.59; 95%CI 0.20 to 1.73. |

Intervention resulted in no differences in clinical outcomes (QoL, readmissions, mortality) with higher costs in the intervention group and improved compliance to 2 of 4 self-carerecommendations. |

| Domingues 2011 (e48) |

RCT Brasilia 01/2005 to 07/2008 |

120 hospitalized patients with decompensated HF 63±13 years, 68% male Exclusion of patients with cognitive neurological sequelae |

In-hospital nursing education (5 visits, 30-60 min) for patients and caregivers, weight chart IG (n=57):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ low |

HF awareness and self-care knowledge score: baseline: 4.6±1.9 vs. 4.5±1.9 3-months: 6.1±2.1 vs. 5.8±1.9 |

Intervention might improve awareness and self-care knowledge (MD 0.30; -0.55 to 1.15), but did not decrease mortality and hospitalizations. |

| Holland 2007 (e22) |

RCT United Kingdo m 12/2003 to 03/2005 |

339 hospitalized HF patients due to emergency issues 77±9 years, 63% male NYHA: 6/27/34/33% |

IG (n=169):

|

low/ low/ high/ high/ low/ low |

Drug adherence (MARS score): baseline: 23.8 vs. 23.6 6-months: 23.7 vs. 23.6 |

Intervention had no effects on mortality, readmissions, QoL and medication adherence scores (MD 0.12; 95% CI -0.48 to 0.73). |

| Israel 2 013 (e16) |

RCT USA enrollme nt through 06/2012 |

732 CVD patients (108 with HF) admitted to the internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology or orthopedics service ≥18 years, 38% male Hypertension: 75% Hyperlipidemia: 61% Exclusion of patients with dementia, cognitive impairment or severe psychiatric or psychosocial disorders |

IG (n=486, 142 with HF):

|

low/ unclear/ low/ unclear/ low/ high |

Underutilization of HF drugs 3-months: ACEI or ARB: 17.1 vs. 29.7 vs. 30.6% β -blockers: 20.0 vs. 21.6 vs. 19.4% |

Intervention had no effect on the underutilization of ACEI or ARB (enhanced IG vs. CG: RD 0.13; 95%CI -0.06 to 0.33, minimal IG vs. CG: RD 0.01; 95%CI -0.20 to 0.22) and β blockers (enhanced IG vs. CG: RD -0.01; 95%CI -0.19 to 0.18, minimal IG vs. CG: RD 0.02; 95%CI -0.21 to 0.16). |

| Jaarsma 2000 (e33) |

RCT Netherla nds 05/1994 to 03/1997 |

186 hospitalized HF patients 72±9 years, 60% male NYHA III/III-IV/IV: 17/22/61% Diabetes: 32% Hypertension:25% Exclusion of patients with a psychiatric diagnosis |

IG (n=89):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ unclear |

Self-care (modified SCB scale): baseline: 8.9±3.0 vs. 9.5±3.0 3-months: 11.6±3.1 vs. 10.2±3.3 9- months: 10.4±3.1 vs. 10.1±2.9. |

Intervention can improve self-care behavior over a short time, but not over a longer follow-up (MD0.3; 95%CI -0.058 to -1.18), might be successful in improving QoL, but did not reduce mortality. |

| Jurgens 2013 (e41(e) |

RCT USA |

105 HF patients admitted to the hospital, referred from community health care providers or recruited with advertisements 68±12 years, 68% male NYHA I-II/III/IV: 15/48/37% Exclusion of patients with major diagnosed psychiatric illness |

Weight-scales, HF-self-care booklet written at the 6th to 8th grade level IG (n=53):

|

low/ unclear/ unclear/ low/ low/ low |

Self-Care (SCHFI) Maintenance: baseline 56.8±22.0 vs.57.5±24.0 3months:76.9±18.4 vs. 70.8±21.2 Management: baseline: 48.2±19.3 vs. 43.8±21.1 3-months: 60.4±27.2 vs.61.1±22.5 |

Intervention had no influence on mortality, readmissions and selfcare management (MD 0.7; 95%CI -0.7; -10.6 to 9.1) and might improve self-care maintenance (MD 6.1; 95%CI -1.7 to 13.9). |

| LaPointe 2006 (e17) |

c-RCT USA 01/2001 to 09/2001 |

45 medical practices with 2717 HF patients 69 years, 67% male NYHA: 5/12/13/8% |

Patients receive a 1-page summary of the evidence for beta-blocker use and a patient-oriented brochure for distribution IG (n=23 practices with 1701 patients): Additional patient education videotapes Feedback on beta-blocker use of their patients with HF Provider internet education Access to telephone communication with a HF expert Control group (n=22 practices with 930 participants): No further intervention |

unclear/ unclear/ low/ high/ low/ high | Mean proportion of patients taking β blocker within practices: 12-months: 66 vs. 63% |

Intervention did not change the use of β blocker (RD 0.03; 95%CI -0.01 to 0.07). |

| Laramee 2003 (e21) |

RCT USA 07/1999 to 02/2001 |

287 hospitalized HF patients 71±12 years, 54% male NYHA: 16/43/33/2% Diabetes: 43% Hypertension: 74% Hyperlipidemia: 57% Exclusion of patients with cognitive impairment or longterm hemodialysis |

IG (n= 141):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ low |

Adherence scores: 3-months (higher better): daily weighting: 4.6 vs. 3.1, p<.001 check for edema: 4.8 vs. 4.6, p=.02 low salt diet: 4.8 vs. 4.4, p<0.001 fluid restrictions: 5.0 vs. 4.6, p=.003 medications: 5.0 vs. 4.9, p=.04 ACEIs or ARBs: 84 vs. 80% β -blocker: 70 vs. 62% |

Intervention did not change readmission rates but may have improved adherence to some lifestyle recommendations and medications. - |

| López- Cabezas 2006 (e13) |

RCT Spain 09/2000 to 08/2002 |

134 hospitalized HF patients 76±9 years, 44% male NYHA I-II/II-IV: 86/14% Diabetes: 34% Hypertension: 61% Renal Failure: 32% Exclusion of patients with any type of dementia or disabling psychiatric disease |

IG (n=70):

Standard care |

low/ low/ high/ high/ low/ unclear |

Treatment compliance, reliable patients: 6-months: 91.1 vs. 69% 12-months: 85 vs. 73.9% |

Intervention might reduce the number of new admissions and deaths and improve QoL. It can improve medication compliance with potential long-term differences (RD 0.11; 95%CI -0.01 to 0.32). |

| Luttik 2012 (e14) |

RCT (non- inferiorit y trial) Netherla nds |

189 HF patients visiting an outpatient HF clinic 73±11 years, 64% male NYHA III/III-IV/IV: 17/22/61% Diabetes: 34% Exclusion of patients with current psychiatric disorder |

Optimal treatment and patient education in a outpatient HF clinic IG (n=97): Follow-up in primary care with no scheduled visits in the HF clinic over 12 months CG (n=92): Follow-up at a specialized HF clinic and care as usual over 12 months |

unclear/ unclear/ low/ low/ high/ low |

Patient adherence over 12 months: total score: 92.3 vs. 94.4% ACE inhibitor/ARB: 93.5 vs. 95.2% β -Blocker: 93.5 vs. 94.9% MRA: 87.1 vs. 93.3% |

Intervention shows non-inferiority in maintenance to guideline adherence and patient’s medication adherence (RD -0.02; 95%CI -0.11 to 0.07) and no differences in the number of deaths and readmissions. |

| Mejhert 2004 (e19) |

RCT Sweden 01/1996 to 12/1999 |

208 hospitalized HF patients 76±7 years, 58% male NYHA: 10/62/37/1% Diabetes: 22% Hypertension: 31% Exclusion of patients with dementia |

- IG (n=103):

|

unclear/ unclear/ unclear/ high/ high/ low |

Goal doses of ACE: 18-months: 88 vs. 74% |

Intervention had no favorable effect on QoL, mortality or readmission rate but can optimize medication adherence (RD 0.14; 95%CI 0.04 to 0.24). - |

| Murray 2007 (e3) |

RCT USA 02/2001 to 06/2004 |

314 HF stable ambulatory patients 62±8 years, 33% male NYHA: 19/41/35/5% Diabetes: 65% Hypertension: 96% Exclusion of patients with dementia |

- IG (n=122):

|

low/ high/ low/ low/ low/ low |

Adherence to medication: intervention period: 78.8 vs. 67.9% 3-months postintervention period: 70.6 vs. 66.7% |

Intervention can improve medication adherence during intervention period (MD 10.9; 95%CI 5.0 to 16.7). The benefit probably requires constant intervention because the effect dissipated in the postintervention period (MD 3.9; 95%CI -2.8 to 10.7). The intervention can reduce the number of all-cause readmission to the hospital or emergency department and slightly reduces mortality. |

| Mussi 2013 (e31) |

RCT Brazil 10/2009 to 11/2012 |

200 hospitalized HF patients due to decompensation 63±13 years, 63% male NYHA: 7/41/41/11% Diabetes: 36% Hypertension: 69% Depression: 22% |

- IG (n=101):

|

low/ unclear/ low/ high/ high/ low |

Self-care (EHFScBS): baseline: 34.4±7.7 vs. 34.0±7.7 6-months: 22.4±6.5 (better) vs. 30.9±7.3 Correct answers to treatment adherence: baseline: 46.3±16.2 vs. 45.2±16.4% 6-months: 71.2±13.8 vs. 55.0±15.0% |

Intervention can improve knowledge on HF, selfcare (MD 8.5; 95%CI 6.3 to 10.8) and knowledge on treatment adherence (MD 14.8; MD 95%Ci 10.0 to 19.7) with no influence on mortality. |

| PetersKlimm 2010 (e37) |

RCT German y 06/2006 to 01/2007 |

199 ambulatory HF patients with former hospitalization from 31 physicians 70±10 years, 73% male NYHA: 3/66/30/1% Diabetes: 34% Hypertension: 79% Depression: 20% Dyslipidemia: 70% |

- IG (n=99):

|

low/ low/ high/ high/ low/ low |

Self-care (EHFscBS): Baseline: 25.4±8.4 vs. 25.0±7.1 12-months: 21.2±6.4 vs. 24.8±6.7 |

Intervention had only small influence on QoL, mortality and readmissions, but can improve self-care (MD 3.6; 95%CI 1.6 to 5.7). |

| Powell 2010 (e15) |

RCT USA 10/2001 to 19/2004 |

902 ambulatory and hospitalized HF patients 64±14 years, 53% male NYHA II/ III: 68/32% Diabetes: 40% Hypertension: 75% Major depressive symptoms: 29% Exclusion of patients with psychiatric comorbid conditions |

IG (n=451):

CG (n=451): Education by 18 HF tip sheets on the same schedule but delivered by mail and telephone contact to answer questions |

unclear/ low/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Adherence to ACEI or BB therapy decreased over 12 months in both groups from 61.6 vs. 63.6% by 7 percent points Self-efficacy improved in both groups by 0.2 points Salt intake (≤2400 mg/d): 12-months: 28 vs. 18%. |

The intervention did not reduce death or HF hospitalization, improve QoL, self-efficacy and drug adherence (OR 0.84; 95%CI 0.6 to 1.18) and can slightly reduce salt intake (RD 0.10; 95%CI 0.05 to 0.15). |

| Riegel 2004 (e42) |

RCT USA 1999 to 2001 |

88 hospitalized HF patients 73±13 years, 42% male NYHA: 5/32/44/19% Diabetes: 46% Hypertension: 82% Exclusion of patients with cognitive impairment |

- IG (n=45)

|

low/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ high |

Self-care (SCHFI): baseline: 147.4±38.7 vs. 175.3±36.1 3-months: 159.2±46.3 vs. 178.4±29.6 Maintenance: baseline: 63.0±19.4 vs. 64.3±18.6 3-months: 74.5±18.3 vs. 68.9±15.6 Management: baseline: 34.7±16.8 vs. 44.9±14.9 3-months: 38.0±18.2 vs. 46.4±17.7 |

Intervention increased readmissions and might improve self-care maintenance (MD 5.6; 95%CI -5.2 to 16.4). It was not able to improve final total self-care scores (MD -19.2: -40 to 1.6) and self-care management (MD -8.4; 95%CI -19.7 to 2.9) due to high baseline differences. |

| Rodriguez- Gázquez 2012 (e34) |

RCT Columbi a 2010 |

63 HF patients attending a CV health program at a hospital institution 68±11 years, 49% male NYHA I-III (mean±SD): 2.2±0.7 Diabetes: 33% Hypertension: 81% Renal failure: 16% Dyslipidemia: 16% Depression: 3% |

- IG (n=33):

|

low/ high/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Adherence to pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment (SCB): baseline: 40.0±6.2 vs. 43.4±5.7 9-months: 52.2±10.1 vs. 48.5±9.0 |

Intervention might improve self-care in patients with HF (MD 3.7; 95%CI -1.35 to 8.75) with no influence on mortality and hospitalization. |

| Ross 2004 (e25) |

RCT USA 09/2001 to 12/2001 |

107 HF patients followed in a specialty HF clinic 56 years, 77% male |

- IG (n=54):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

General Adherence at 12 months: 85 vs. 78, p=0.01 Medication Adherence: 3.6 vs. 3.4, p=0.15 |

Intervention can improve general adherence (MD 6.4; 95%CI 1.8 to 10.9) and medication adherence (MD 0.2; 95%CI -0.1 to 0.6) with more emergency department visits in the IG and no influence on mortality and QoL. |

| Seto 2012 (e46) |

RCT Canada 09/2009 to 02/2010 |

100 ambulatory HF patients at a HF clinic 54±14 years, 79% male NYHA II/II-III/III/IV: 43/11/42/4% |

- IG (n=50):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ low |

Self-care (SCHFI): Maintenance: baseline: 65.5±18.6 vs. 58.9±18.7 6months:73.3±11.6 vs. 65.5±15.8 Management: baseline: 58.1±24.5 vs. 57.9±22.4 6-months: 68.6±16.0 vs. 69.3±18.3 |

Intervention can improve self-care maintenance (MD 7.8; 95%CI 1.8 to 13.8), but not self-care management (MD -0.7; 95%CI -11.5 to 10.1). It improved Qol, but not hospitalization, mortality and emergency care visits. . |

| Shearer 2007 (e43) |

RCT USA winter 2001 to fall 2003 |

90 hospitalized HF patients 76±8 years, 64% male NYHA:0/43/49/8% |

- IG (n=45):

|

unclear/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Self-Management of HF: baseline: 16.4±2.5 vs. 17.0± 2.6 3-months: 19.6±2.2 vs. 18.0±3.0 |

Intervention had no influence on purposeful participation or QoL, but can improve selfmanagement of HF (MD 1.6; 95%CI 0.3 to 2.8). |

| Shively 2013 (e47) |

RCT USA |

84 HF patients, hospitalized or emergency department visit within the previous 12 months 66±11 years, 83% male NYHA (I /II/III): 4/33/52% ≥3 comorbid conditions: 71% Exclusion of patients with psychiatric problems |

- IG (n=43):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ high/ low/ low |

Self-care (SCHFI): baseline: 56.7±17.5 vs. 64.7±20.7 6-months: 65.1±22.7 vs. 70.0±19.2 |

Intervention can improve patient activation selfmanagement selfconcept and adherence and may improve patients’ self-care. Hospitalization were improved in patients with low or high baseline activation level- |

| Smeulders 2009 & 2010 (e35, 58) |

RCT Netherla nds 10/2004 to 01/2006 |

317 HF patients with a limitation of physical activity 67±11 years, 73% male NYHA: 0/67/33/0% |

- IG (n=186):

|

low/ low/ high/ low/ unclear/ high |

Self-care (EHFscBS): baseline: 47.7±6.0 vs. 48.3±6.7 direct follow-up: 49.8±5.8 vs. 48.7±6.5 12-months: 49.2±6.3 vs. 49.2±6.6 |

Program can improve self-care behavior directly after the program (MD 1.5; 95%CI 0.4 to 2.5), but they did not achieved over 12 months (MD 0.9; 95%CI -2.2 to 0.35) with no influence on mortality and hospital admissions. |

| Strömberg 2006 (e49) |

RCT Sweden |

154 HF patients visiting a nurse-led HF clinic 70±10 years, 71 % male |

Individualized patient education from a HF-nurse during a follow-up visit in a nurse-led HF-clinic (1 hour) IG (n=82):

|

low/ unclear/ low/ low/ low/ high |

Compliance with treatment and selfcare: baseline: 11.88 vs. 11.89 mean change over 6 months: -0.21 vs. 0.09 (p=0.09) |

Intervention can improve knowledge, but not compliance, QoL and mortality. |

| Thompson 2005 (e26) |

c-RCT UK |

106 hospitalized HF patients 73±13 years, 73 % male NYHA III: 75% Charlson comorbidity index: 2.5±1.4 Diabetes: 20% |

IG (n=58):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ unclear/ low/ low |

Treatment adherence: few differences at 6 months (not reported). Na restricted diet: 8.9±2.3 vs. 7.3±1.9 (better in IG) |

Intervention slightly decreased risk of death or readmissions and QoL with slight difference in general adherence and Na restricted diet (MD 1.6; 95%CI 0.75 to 2.34). |

| Tsuyuki 2004 (e18) |

RCT Canada 09/1999 to 04/2000 |

276 hospitalized HF patients 72±12 years, 58 % male NYHA: 13/50/33/4% |

IG (n=140):

|

low/ low/ low/ low/ low/ low |

ACE inhibitor adherence: over 6 months: 83.5±29 vs. 86.2±29%. | Intervention did not improve ACE inhibitor use (MD -2.7; 95%CI 9.5 to 4.1), but might reduce CVD-related emergency room visits. |

| Wakefield 2008 & 2009 (e4, e59) |

RCT USA 07/2002 to 09/2005 |

148 hospitalized HF patients due to exacerbation 69±10 years, 99 % male NYHA: 0/28/65/7% |

IG (n=99):

|

unclear/ low/ high/ low/ high/ low |

Compliance scores: 3-months: 88 (both intervention groups) vs. 91% 6-months: 86 vs. 91% Self-efficacy to manage disease: 6-months: 6.2±2.0 vs. 7.1±2.2 vs. 7.2±2.0 to manage symptoms: 6-months: 6.0±2.3 vs. 5.8±2.4 vs. 6.2±2.5 |

Intervention can decrease readmission in both intervention groups with no differences between these groups, higher mortality in the videophone group and no differences in QoL. It shows no long-term differences in compliance (RD -0.05; 0.18 to 0.08), selfefficacy to manage disease (MD -0.5; 95%CI -1.4 to 0.4) and symptoms (MD -0.3; 95%CI -1.3 to 0.7). |

| Welsh 2013 (e57) |

RCT USA |

52 HF patients from a cardiologic clinic, community and university hospital 62±10 years, 54 % male NYHA II/III-IV: 48 / 52% Exclusion of patients with cognitive disorders or the presence of a major psychiatric disorder other than depression |

- IG (n=27):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Self-care management of a low sodium diet: dietary sodium intake: 6-months: 2262 ±925 vs. 3164 ±886 (p=0.011) |

Intervention can decrease dietary sodium intake (MD 901; 95%CI 410 to 1390). |

| Zamanzadeh 2013 (e44) |

RCT Iran 07/2011 to 09/2011 |

80 hospitalized HF patients 64±11 years, 54% male NYHA III/IV : 48/52% Hypertension: 36% Exclusion of patients with mental illness |

IG (n=40):

|

low/ unclear/ high/ low/ low/ low |

Self-care (SCHFI): Maintenance: baseline: 18.5±12 vs. 21.9±14.6 3-months: 75.1±20.7 vs. 31.9±15.5 Management: baseline: 11.9 ±11.9 vs. 16.7±16.7 3-months: 66.5±15.3 vs. 30.3±17.6 |

Intervention can improve self-care behavior in self-care maintenance (MD 43.2; 95%CI 35.1 to 51.3) and management (MD 36.2; 95%CI 28.9 to 43.5). |

CG, Control group; CI, confidence interval; c-RCT, cluster randomized control trial; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DMP, disease management program; EHFscBS, European Heart Failure Self-care behavior scale; HF, heart failure; IG, intervention group; n, number of randomized participants; NYHA, New York Heart Association; MD, mean difference; OR, Odds Ratio; QoL, Quality of life; RD, risk difference; RCT, randomized control trial; SCB, self-care behavior; SCHFI, Self-Care of Heart failure index;

MD, OR, RD>0 describe better adherence in IG

Risk of bias: I, random sequence generation; II, allocation concealment, III, blinding of outcome assessment; IV, incomplete outcome data; V: selective reporting; VI: other bias

Discussion

Adherence to medication treatment as well as adherence to accompanying lifestyle recommendations can be improved by means of appropriate interventions. The effect sizes we found were lower than assumed, not least because of the pronounced heterogeneity of the included studies. Sustained effects can be expected especially for multimodal approaches that are provided with interactive feedback options for longer time periods.

Improved adherence to medication treatment

Approaches that entailed, among others, maintaining contact with patients for a lengthy period of time in order to practice adherent behaviors and check these were particularly effective (eTable 3). Notably, such sustained effects were usually achieved independently of medical doctors—for example, by specially trained nursing staff, doctors’ assistants (26– 30), or pharmacists (29).

Moderately positive, but long-term, effects on quality of life, adherence to medication therapy, and self-care were shown as a result of complex bundles of measures (simplified dosing regimen, education for patients, brochures, keeping a heart failure diary with discussion of the documented entries) (29). Similarly, bundled interventions (telephone monitoring, smoking cessation courses, home visits in instability, advisory hotline) (27) had a positive effect on adherence to medication treatments and on mortality. The large GESICA study (which included 1518 patients) (28) showed that combined interventions had a sustained moderate success (telephone monitoring, information brochure, patient education provided by nursing staff, and recommendations on adjusting medications and emergency admissions).

By contrast, no sustained effects were seen for approaches whose main focus was on educational/training measures in hospital and included only very few contacts with patients for the extended observation period (for example, e3, e16, e49).

Our results therefore confirm the results of other review articles on the adherence to medication treatment: the long-term use of complex patient centered interventions is required for the intervention to be successful. However, this does not reach all patients, with the result that altogether the effects on adherence and clinically important endpoints are rather small (31, 32).

Improved adherence to lifestyle modifications

We estimated the efficacy of interventions to improve adherence to lifestyle modifications in studies with very heterogeneous endpoints; summarizing the results is therefore difficult. What seems promising, however, is multidisciplinary cooperation with a combination of inpatient and outpatient care (eTable 4). This should include primarily patient education/training with individual treatment planning in hospital and subsequent regular outpatient contact, with repeated training sessions, medical histories, and examinations provided by non-doctor medical professionals (33– 35). The efficacy of such measures can be supported by further interventions, such as:

Care provided in a special clinic run by nursing staff (35)

Structured telephone contact

Medication adjustment by nursing staff after discussion with cardiologists

Psychosocial care

Help provided in a patient’s domestic environment

Creating a therapeutic bond that is based on trust.

Some studies (e33, e36) showed improved self-care at first follow-up, but they did now show any sustained improvements in results beyond the duration of the intervention. The therapeutic bond with a trusted professional—whether by telephone contact or home visit, or in the setting of a training/educational measure—obviously has a crucial role in improving adherence. A merely technically based solution without human interaction seems neither immediately effective nor able to provide a sustained effect (e23). In another study (e42) patients in the intervention groups were trained up as mentors, who were available to a particular assigned patient personally or by telephone whenever required. Although the implementation was linked to a person, self-care did not notably improve. The possible reason may be in the lack of competence that is perceived in a patient mentor—by contrast to medical personnel, encounters with whom a priori inspire a greater amount of confidence.

The efficacy of the collaboration of acute hospitals and rehabilitation facilities, and the formation of multidisciplinary networks in tertiary prevention of cardiovascular disorders was also emphasized by Labrunée et al (36).

Effect on clinical outcomes

The present review found that improved adherence was associated with additional positive effects on clinically relevant outcomes, which range from improved quality of life to reduced hospital stays to lower mortality. Further review articles have shown the lack of efficacy of patient training alone on clinical outcomes (37) and have shown the need for further patient centered measures in a patient’s domestic environment, such as structured telephone contacts and telemonitoring (38), or multidisciplinary care (39).

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is the fact that on the one hand, certain groups—such as patients with depression or dementia syndromes—in whom the risk for lower adherence is particularly great, were excluded from many studies. On the other hand, the studies are probably representative for the group of patients requiring treatment with regard to age and disease severity.

This review includes exclusively strategies for the implementation of measures recommended these days, as the literature search was restricted to the time period starting after the year 2000. A bias to the observed treatment effects by selective publication of positive effects of the intervention on adherence cannot be excluded, especially in studies with primary clinical endpoints. The extensive heterogeneity of the described studies and the lack of objectivity in capturing adherence with the resulting heterogeneous treatment effects should be seen as a critical issue, so that the main result of this review is not the pooled treatment effects but the presentation and discussion of effective interventions.

Conclusion

In the practical implementation of adherence-promoting packages of measures, specialized nursing staff in hospitals, and specially trained doctors’ assistants working in doctors’ private practices are likely to have a crucial part in establishing such measures in a patient-centered way in future. Active participation of patients in the context of shared decision making (40) should form the basis for deciding on individual measures aiming to improve adherence. To this end, patients should be enabled—on the basis of comprehensible, evidence-based information tailored to them—to develop realistic expectations of their own disease course, and to be active and adopt individual responsibility in terms of dealing with their disease and treatment measures.

Key Messages.

This systematic review investigates the efficacy of interventions on adherence to medication therapies and implementation of lifestyle recommendations in patients with heart failure, and how clinical endpoints improve as a result

Adherence to medication therapies improved in 14 of 24 studies; the proportion of non-adherent patients was lowered by 10 percentage points (95% confidence interval [5; 15]).

Adherence to lifestyle recommendations improved in 31 of 42 studies.

Improved adherence in at least one guideline recommendation reduced in the long term the risk of death or inpatient stays in hospital by 2 and 10 percentage points, respectively.

Improved adherence requires patients’ activity and responsibility in dealing with their disorder and treatment measures. Especially patients with cognitive impairments benefit from additional support provided by specialized nursing staff or doctors’ assistants.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

The authors thank Professor Dr. med. Andreas Klement for his commitment to supervising the entire project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt: Krankenhauspatienten. Vollstationär ¬behandelte Patientinnen und Patienten (einschließlich Sterbe- und Stundenfälle) in Krankenhäusern nach der ICD-10 im Jahr. www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Gesundheit/Krankenhaeuser/Tabellen/20DiagnosenInsgesamt.html. 2014 (last ¬accssed on 25 February 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in US. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:3288–3298. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Stevens GA, Boerma T, White RA, Tobias MI. Causes of international increases in older age life expectancy. Lancet. 2015;385:540–548. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1333–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Gobrani M, El Khatib C, Pillon F, Gueyffier F. Beta-blockers for the prevention of sudden cardiac death in heart failure patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driscoll A, Currey J, Tonkin A, Krum H. Nurse-led titration of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, and angiotensin receptor blockers for people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009889.pub2. CD009889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faris RF, Flather M, Purcell H, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJS. Diuretics for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003838.pub3. CD003838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flather MD, Yusuf S, Kober L, et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. Lancet. 2000;355:1575–1581. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heran BS, Musini VM, Bassett K, Taylor RS, Wright JM. Angiotensin receptor blockers for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003040.pub2. CD003040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CD, Holmes GM, DeWalt DA, et al. Self-reported recall and daily diary-recorded measures of weight monitoring adherence: associations with heart failure-related hospitalization. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KS, Lennie TA, Dunbar SB, et al. The association between regular symptom monitoring and self-care management in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;30:145–151. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abshire M, Xu J, Baptiste D, et al. Nutritional interventions in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. J Card Fail. 2015;21:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Chronische KHK - Langfassung. Konsultationsfassung. www.khkversorgungsleitlinien.de. (last accessed on 25 February 2015)

- 15.McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabaté E. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. WHO adherence to long term therapies project, global adherence interdisciplinary network: adherence to long term therapies: evidence for action. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee D, Mansi I, Bhushan S, Parish R. Non-adherence in at-risk heart failure patients: characteristics and outcomes. J Nat Sci. 2015;1 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrao G, Rea F, Ghirardi A, et al. Adherence with antihypertensive drug therapy and the risk of heart failure in clinical practice. Hypertension. 2015;66:742–749. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unverzagt S, Klement A, Meyer G, Prondzinsky R. Interventions to enhance adherence to guideline recommendations in secondary and tertiary prevention of heart failure: a systematic review. J Clin Trials. 2014;4 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haasenritter J, Panfil EM. Instrumente zur Messung der Selbstpflege bei Patienten mit Herzinsuffizienz. Ergebnisse einer Literaturanalyse. Pflege. 2008 doi: 10.1024/1012-5302.21.4.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, Martensson J, Dracup K. Development and testing of the European heart failure self-care behaviour scale. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:363–370. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riegel B, Carlson B. Is individual peer support a promising intervention for persons with heart failure? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19:174–183. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26..Brotons C, Falces C, Alegre J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a home-based intervention in patients with heart failure: the IC-DOM study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:400–408. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)71667-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galbreath AD, Krasuski RA, Smith B, Stajduhar KC, Kwan MD, Ellis R. Long-term healthcare and cost outcomes of disease management in a large, randomised, community-based population with heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113 doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148957.62328.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GESICA investigators. Randomised trial of telephone intervention in chronic heart failure: DIAL trial. BMJ. 2005;331 doi: 10.1136/bmj.38516.398067.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadik A, Yousif M, McElnay JC. Pharmaceutical care of patients with heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:183–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu JR, Corley DJ, Lennie TA, Moser DK. Effect of a medication-taking behavior feedback theory-based intervention on outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molloy GJ, O’Carroll RE, Witham MD, McMurdo ME. Interventions to enhance adherence to medications in patients with heart failure: a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:126–133. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4. CD000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bocchi EA, Cruz F, Guimaraes G, et al. Long-term prospective, randomized, controlled study using repetitive education at six-month intervals and monitoring for adherence in heart failure outpatients: the REMADHE trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1:115–124. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.107.744870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasper EK, Gerstenblith G, Hefter G, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy of multidisciplinary care in heart failure outpatients at high risk of hospital readmission. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strömberg A, Martensson J, Fridlund B, Levin LA, Karlson JE, Dahlstrom U. Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure: results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1014–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labrunée M, Pathak A, Loscos M, et al. Therapeutic education in cardiovascular diseases: state of the art and perspectives. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;55:322–341. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown JPR, Clark AM, Dalal H, Welch K, Taylor RS. Patient education in the management of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008895.pub2. CD008895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inglis SC, Clark RA, Dierckx R, Prieto-Merino D, Cleland JGF. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007228.pub3. CD007228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeda A, Taylor SJC, Taylor RS, Khan F, Krum H, Underwood M. Clinical service organization for heart failure. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002752.pub3. CD002752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loh AS, Kriston L, Härter M. Shared decision making in medicine. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104:1483–1488. [Google Scholar]

- e1.Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Urquhart J, et al. Effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on diuretic compliance in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled study. J Card Fail. 2003;9:404–411. doi: 10.1054/s1071-9164(03)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Kasper EK, Gerstenblith G, Hefter G, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy of multidisciplinary care in heart failure outpatients at high risk of hospital readmission. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:714–725. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Wakefield BJ, Ward MM, Holman JE, et al. Evaluation of home telehealth following hospitalization for heart failure: a randomized trial. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:753–761. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Wu JR, Corley DJ, Lennie TA, Moser DK. Effect of a medication-taking behavior feedback theory-based intervention on outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]