Abstract

Background

Proper infant nutrition promotes healthy growth and development and lowers the risk of disease in later life.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent articles retrieved by a selective search, including guidelines, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews.

Results

Infants should be exclusively breast-fed until at least the age of 4 months. Infants who are no longer being breast-fed, or no longer exclusively so, should be given commercially available low-protein infant formula containing long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Infants with a family history of allergy should be fed with infant formula based on hydrolyzed protein until complementary feeding begins. Complementary feeding should be initiated no earlier than the beginning of the 5th month and no later than the beginning of the 7th; it should include iron derived from meat, as well as fish once or twice a week. Later initiation of complementary feeding is associated with an increased risk of allergies and is not recommended. Ordinary cow’s milk should not be drunk in the first year of life. All infants should be given 2 mg of vitamin K at birth, at 7–10 days, and at 4–6 weeks of age, as well as daily oral supplementation of vitamin D (400–500 IE) and fluoride (0.25 mg).

Conclusion

Physicians should advise families about healthful infant nutrition in order to lay the foundation for lifelong good health through a proper diet.

The rapid growth and development of healthy infants requires a high intake of nutrients and energy per kilogram of body weight (e1, e2). Infants’ nutrient reserves are limited; a nutritional intake that is too low to meet the infant’s needs can lead to failure to thrive and to impaired neural development. An increasing body of evidence indicates that early nutrition has long-lasting effects on health and performance in adulthood (“early nutrition programming of long-term health”) (1, 2). Nutritional counseling based on solid scientific evidence is an important duty of the physician. In Germany, joint recommendations on infant nutrition have been issued by the German Society of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin) (3, 4) and the federally sponsored Network “A Healthy Start in Life” (4). On the European level, the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) has also published its positions on these issues (5, 6, e3).

Learning objectives

This article is intended to acquaint the reader with

current recommendations on breastfeeding,

the alternatives to nutrition with mother’s milk,

ways to introduce complementary feeding.

Early nutrition and health.

Nutritional counseling based on solid scientific evidence is an important duty of the physician. There is increasing evidence that early nutrition has long-lasting effects on health and performance in adulthood.

Methods

We selectively searched the PubMed database for publications on infant nutrition (key words: “breastfeeding,” “infant formula,” “infant nutrition,” “complementary feeding,” “early nutrition programming”) that were published between 2009 and 2015, after the European position paper on breastfeeding and infant nutrition (5). These publications and the current recommendations in Germany and abroad were evaluated and summarized by the authors; important earlier publications cited in them were also taken into account.

The advantages of breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is the natural means of infant nutrition. The composition of mother’s milk is optimally suited to the needs of the infant.

Breastfeeding

The advantages of breastfeeding, and its duration

Breastfeeding is the natural means of infant nutrition. The composition of mother’s milk is optimally suited to the needs of the infant (3, 5). As long as the mother is taking a balanced diet, her milk gives her child all the important nutrients for growth and normal development. Mother’s milk is, generally speaking, hygienically unproblematic, at the right temperature, and practically always available. It contains not only nutrients, but also many immunologically active components with anti-infectious and anti-inflammatory properties. Breastfeeding lowers the risk of infectious disease. A meta-analysis of studies from industrialized countries revealed that children fed exclusively with formula suffer from acute otitis media twice as often as children who were nourished only on mother’s milk for three to six months (7). If 100 children are breast-fed rather than bottle-fed for six months, roughly 13 cases of acute otitis media are prevented (incidence, 27%) (8). The risk of acute gastroenteritis can be reduced by one-half to one-third (7); thus, six months of breastfeeding in 100 infants can prevent 15–63 episodes of diarrheal disease (annual incidence, 0.9–1.9 episodes) and 2–6 hospital admissions (e4). The mortality of breast-fed infants from sudden infant death syndrome is 15% to 36% lower than that of non-breast-fed infants (7, 9); this implies that breastfeeding can prevent about one such death per 10 000 breast-fed children (incidence, 0.04% [e5]). Meta-analyses of comparative cohort studies have shown that breastfeeding markedly lowers the risk of the child’s suffering from various diseases in later life (5, 7, 10, 11), including:

Bronchial asthma (-27% to -30%; about 2 cases of asthma prevented per 100 breast-fed infants) (e6)

Atopic dermatitis (-32%; about 3 cases of eczema prevented per 100 breast-fed infants)

Obesity (-12%; about 3 cases of obesity prevented per 100 breast-fed infants) (11, e7).

Breastfeeding promotes the emotional bonding of mother and child, as well as the child’s cognitive development. Adolescents and adults who were breast-fed as children have IQ scores that are 2 to 3 points higher than those who were not, after correction for other factors (11, 12). This difference has been ascribed, among other things, to the effect of the omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA), which are deposited in the growing brain in large amounts (13, 14). In a prospective cohort study, 30-year-olds who had been breast-fed as children had IQ scores that were 3.8 points higher than those who had not, as well as an average of 0.9 additional years of education and occupational training, and incomes that were 23% higher (after adjusting for other factors) (15).

Breast-feeding women benefit from more rapid postnatal uterine involution, increased catabolism of the body fat deposited during pregnancy, and a reduction of the risk of breast cancer by approximately 4% (after adjustment for confounders) (7, 16). Breastfeeding for 12 months can prevent roughly 1 case of breast cancer per 200 women (lifetime prevalence, 12.9% [e8).

Breastfeeding and IQ.

Breastfeeding promotes the emotional bonding of mother and child and the child’s cognitive development. Adolescents and adults who were breast-fed as children have IQ scores that are 2–3 points higher, after correction for other factors.

Both parents should be adequately informed about breastfeeding before the child is born, because the father’s support markedly improves the success of breastfeeding and prolongs its duration (17). The baby should be put to the breast within two hours of birth—within 30 minutes if it is at risk for hypoglycemia (3). Difficulties at the onset of breastfeeding are common and lead to early weaning; appropriate counseling by trained personnel (e.g., midwives, lactation counselors, physicians) can help prevent them. If exclusive breastfeeding is not possible, the mother should be encouraged to breast-feed the child at least partially, as this, too, is good for its health (4).

The child should be allowed to determine the frequency of breastfeeding: it should be ad libitum, i.e., the child should drink as often and as much as he or she wants (e9). Most babies drink about 10 to 12 times a day in their first few weeks of life and then only every 3 to 4 hours as they get older. In special situations (e.g., if weight gain is inadequate) the baby should be awakened for feeding. If the baby’s postnatal weight loss exceeds 7–10% of birth weight, or if it does not gain any weight at all in the first seven days, the cause should be investigated. Infants should be breast-fed at least for the first six months, and exclusively so for the first four months. The overall duration of breastfeeding is jointly determined by the mother and child (4).

Exclusively breast-fed infants gain about 500–700 g less weight in their first year than those fed with conventional formula (18). This is apparently causally related to their lower risk of obesity in later life (11, 19, e10, e11).

Substitutes for mother’s milk

Infants that are not (exclusively) breast-fed should be given infant formula (4). Follow-on formulae should only be given once the child is taking complementary feeding (Table 1). The standard infant formulae are based on protein from cow’s milk.

Table 1. Classification of baby formulae.

| Infant formulae are suitable for use as exclusive nutrition during the first six months and can be given for a full twelve months if the child is not being breast-fed | |

|

|

|

|

| Follow-on formulae are suitable from the time that complementary feeding is introduced | |

|

|

|

|

Soybean protein–based infant formulae should only be given on the advice of a physician, particularly in the child’s first six months (20). The quality of the protein in such formulae is inferior to that in formulae based on cow’s milk. There is concern that phytoestrogens, phytates, and high aluminum content in soybean-based formulae may have untoward effects. About 10% of infants that are allergic to cow’s milk proteins also develop an allergy to soybean proteins. For this reason, soybean-based formulae should not be given in the first six months to healthy children or to children with food allergies (20). The indications for soybean-based formula include galactosemia, a rare disease (prevalence 1:40 000), religious or other convictions barring the use of cow’s milk (3, 20), and the feeding of older infants who are allergic to cow’s milk and persistently refuse to drink therapeutic hydrolyzed protein formula.

Substitutes for mother’s milk.

Infants that are not (exclusively) breast-fed should be given infant formula. Follow-on formulae should only be given once the child is taking complementary feeding.

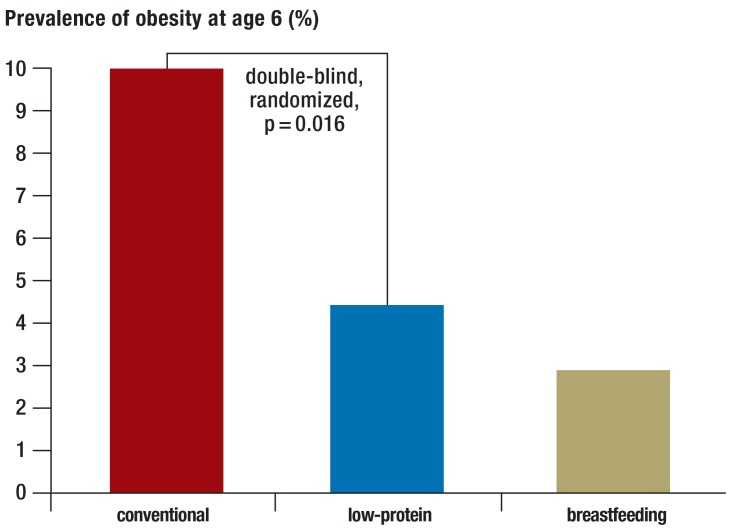

DHA supplementation accompanied by at least equal amounts of ARA is recommended, as it has been reported to have a positive effect on the maturation of vision and on childhood development (14). DHA supplementation without ARA (e.g., fish-oil preparations) is not recommended (21). Infant formulae with a relatively low protein content are now preferred (<2 g/100 kcal or about <1.3 g/100 mL; cf. the protein content of mother’s milk, 1.2 g/100 mL), as they may lessen the risk of obesity in later life (Figure 1) (22).

Figure 1.

In the double-blind, randomized Childhood Obesity Project (CHOP) trial, the prevalence of obesity at age 6 (years) was 10% among children who had been fed with conventional baby formula in the first year of life, compared to only 4.4% among those who had been given low-protein infant formula and 2.9% among those who had been breast-fed (22)

Infant formulae that are supplemented with pre- or probiotic substances have been available for some years now. The supplements found in commercially available formulae are considered safe for healthy infants, but systematic reviews to date have not revealed any clinically relevant benefits (3, 4, 23, 24).

The preparation of home-made baby formula based on cow’s milk, other animal milks, or other substances is explicitly discouraged: the hygienic risk is significant, as is that of nutritional inadequacy. Because of cross-reactions, the milk of animals other than cows is not suitable for the prevention or treatment of allergy to cow’s milk (e12).

Pre- and probiotic supplementation.

The pre- and probiotic supplements found in commercially available formulae are considered safe for healthy infants, but systematic reviews to date have not revealed any clinically relevant benefits.

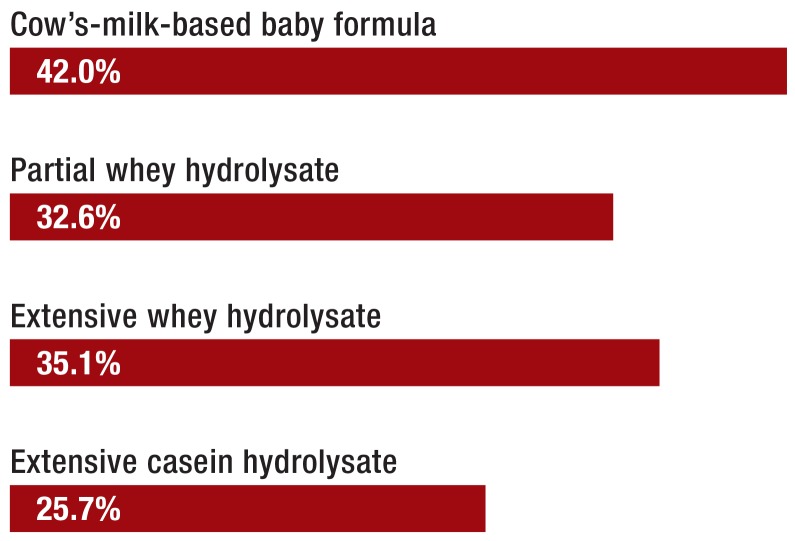

Formula for infants with a family history of allergy

Non–breast-fed or not exclusively breast-fed infants whose siblings or parents suffer from allergies should be given a hypoallergenic infant formula based on hydrolyzed protein (so-called HA formula). The German Infant Nutrition Intervention (GINI) trial showed that children with a family history of allergies were 18% less likely to develop atopic dermatitis up to the age of 10 years if given a suitable HA formula in their first few months of life (after adjustment for other factors) (Figure 2). In this group of children at risk, the administration of HA formula, rather than standard cow’s-milk-based formula, prevented 6.4 cases of atopic dermatitis per 100 children (25). Once complementary feeding has been introduced, normal cow’s-milk-based formula can be given (3).

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence of atopic dermatitis (%) up to age 15 years in children with a family history of allergy who were fed as infants with conventional, cow’s-milk–based baby formula versus protein hydrolysate formulae (p<0.05 for partial whey hydrolysate and extensive casein hydrolysate, after adjustment for confounders) (25)

After complementary feeding is introduced.

Once compementary feeding has been introduced, infants with a family history of allergy can be given normal baby formula based on cow’s milk.

Preparing infant formula in bottles

Powdered infant formula and products heated to ultra-high temperatures are low in microbes, but they are not sterile. Prepared infant formula at temperatures of 25° to 45° C is a good bacterial culture medium. There is a risk (among others) of invasive infection with Cronobacter spp., an organism that is especially dangerous for neonates (whether premature or born at term), infants in the first two months of life, and children with immune deficiencies. Cronobacter can cause meningitis and necrotizing enterocolitis; these conditions are rare (ca. 1:100 000) but associated with high mortality and long-term morbidity (26). Instructions for the storage of bottled formula and pumped mother’s milk are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Maximal storage time for mother’s milk and baby formula (e13–e15).

| Storage temperature | Mother’s milk | Prepared baby formula |

|---|---|---|

| Room temperature | 6–8 hours (thawed mother’s milk, 2 hours) |

2 hours (discard leftover formula) |

| 4°C | 72 hours | 24 hours |

| −20 to −40°C | 6 months | not to be frozen |

Fresh tap water can be used to prepare infant formula. Standing water, i.e., water that has been inside household plumbing for several hours, should be drained off first, because it may contain a higher concentration of heavy metals and because biofilms can form on water faucets (e14, e15). Ordinary tap water should not be used if the household pipes contain lead (as in some old buildings), and water from domestic wells should not be used unless it has been tested. In such cases, the infant formula should be prepared with suitable bottled water. The use of common household water filters is discouraged, as these may contain high concentrations of microbes or other contaminating substances (3, e14).

The water used to prepare infant formula should be lukewarm (maximum, 40°C) to prevent scalding and the destruction of nutrients. Bottles and nipples should be thoroughly cleaned after each meal, but there is no need for bottles or silicone nipples to be boiled or sterilized for home use. Rubber nipples should be occasionally boiled or changed (4).

Complementary feeding

Complementary feeding should be initiated no earlier than the beginning of the fifth month and no later than the beginning of the seventh (3, 4, 6, 27). From the age of 4 to 5 months onward, most children can propel boluses of semisolid food with their tongues. From the age of 5 to 6 months, they begin to show interest in (or rejection of) food, with much variation from one child to another. Parents should initiate complementary feeding on the basis of the child’s showing interest in food, as well as other factors.

When to introduce complementary feeding.

Complementary feeding should be initiated no earlier than the beginning of the 5th month and no later than the beginning of the 7th.

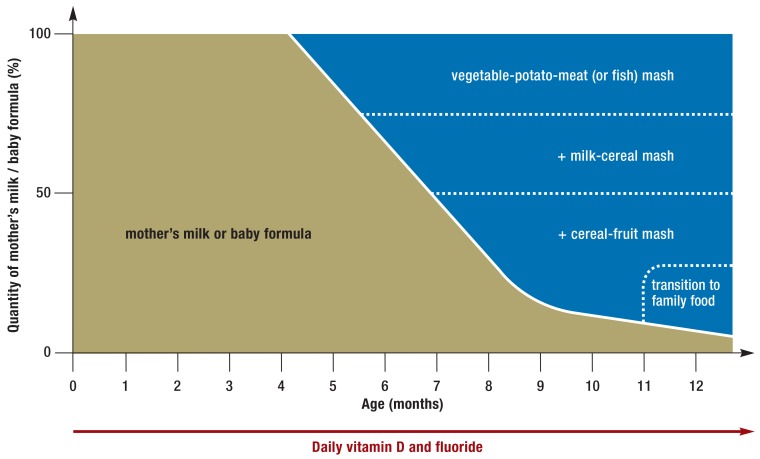

In Germany, the procedure diagrammed in Figure 3 has proven useful. A mixture of vegetables, potato, and meat is given as the infant’s first semisolid food (with oily fish instead of meat one or two times per week) to provide highly bio-available iron and zinc. The infants’s iron reserves are nearly depleted after 4–6 months of exclusive breastfeeding, and the iron requirement per kilogram of body weight reaches a peak in the second half of the infant’s first year. The early consumption of meat, liver, and fish is associated with thriving growth and good cognitive development later on in childhood (14, e3).

Figure 3.

Percent composition of the diet in the infant’s first year with the introduction of complementary feeding and with a transition to family food at the end of the first year. Modified from (3)

Animal proteins.

The early consumption of meat, liver, and fish is associated with thriving growth and good cognitive development later on in childhood.

The introduction of complementary feeding takes patience: any new kind of semisolid food has to be offered an average of eight times before the infant accepts it completely (28). Roughly one additional milk meal per month is replaced by a milk-and-cereal or fruit-and-cereal mixture (Figure 3). Variety in ingredients is desirable to help promote the development of taste. In a large British cohort study, 6-month-old infants who were eating a wide variety of home-made vegetable meals went on to consume more vegetables as school-aged children (29).

“Baby-led weaning” has recently been proposed as a method of introducing complementary feeding: infants are offered appropriately sized foods that they can take in their hands and put in their mouths themselves (e16). It is hoped that this will promote autonomy (e17).

A systematic review of baby-led weaning, however, has shown that it delays the initiation of complementary feeding and may therefore have a deleterious nutritional effect, as well as impairing the prevention of allergies (30). Moreover, solid foods of certain kinds can be aspirated (root vegetables, hard bread crusts, nuts).

Family diet.

Around the first birthday, regular family food can be introduced in steps, with the goal of balanced family nutrition consisting of three meals a day with two snacks in between.

It is, therefore, still recommended that complementary feeding should be initiated with semisolid food, although infants can, of course, be given certain solid, but not hard foods (e.g., banana pieces) that they can bring to the mouth with their own hands (3, 4). Around the first birthday, regular family food can be introduced in steps, with the goal of balanced family nutrition consisting of three meals a day with two snacks in between.

Home-made vs. commercial foods for complementary feeding

Home-made and commercial (ready-made) foods each have their own advantages (Table 3). Whatever type of food is given, very salty, spicy, and sweetened foods should be avoided.

Table 3. The advantages of home-made and commercial complementary baby food.

| Home-made baby food | Commercial baby food |

|---|---|

| Wider variety of tastes | Must conform to strict governmental restrictions on the content of harmful substances |

| Lower cost | Convenient, saves time |

| Enriched with critical nutrients (iron, iodine, zinc, vitamin D), ensures adequate nutrient intake more reliably |

The risk of nutritional inadequacy is higher if the infant’s food is home-made. Iodine is present only in small amounts in home-made baby food; therefore, either the addition of commercially available, iodine-enriched baby food or iodine supplementation (ca. 50 µg/day) is advisable (31). Baby-food pouches (“drinkable” baby foods) are not recommended. Complementary feedings should be given with a spoon, not taken as a beverage (3, e18).

Home-made baby food for complementary feeding (Box) should be prepared immediately before eating or stored in a refrigerator for no more than 24 hours. It can also be frozen for up to a few months. Honey, even if pasteurized, should not be given to infants because of the risk of botulism (4).

Box. Home-made complementary foods.

Sample recipes for home-made baby food for complementary feeding, modified from (2). Alternatively, commercial baby food can be given.

-

Vegetable-potato-meat mash

90–100 g of vegetables

40–60 g of potato

15–20 g of fruit juice

20–30 g of meat

8–10 g of rapeseed oil

-

Milk-cereal mash

200 g of milk or prepared baby formula

20 g cereal flakes

20 g fruit juice or purée

-

Cereal-fruit mash

20 g cereal flakes

90 g water

100 g fruit

Home-made vs. commercial foods for complementary feeding.

Home-made and commercial (ready-made) foods each have their own advantages. Whatever type of food is given, very salty, spicy, and sweetened foods should be avoided.

Complementary feeding and food intolerance

Some medical specialty societies used to recommend that the intake of certain foods that commonly provoke allergic reactions, such as eggs, fish, or peanuts, should be delayed as long as possible, till the age of at least one year or even three years. There is no evidence, however, that this prevents allergies, even in children with a family history of allergy (32). On the contrary, the later introduction of allergenic foods has been found to be associated with increased allergic sensitization (33, 34). If the complementary feeding of an infant regularly includes fish, the risk of developing atopic diseases later is lower (14, 35, e19, e20).

A randomized trial carried out in selected children at high risk of allergy revealed that peanut allergy was much rarer up to the age of 5 years in children who had been given ground peanuts to eat at age 4–11 months, compared with the later introduction of peanuts (1.9% vs. 13.7%) (e21). It must be borne in mind, however, that peanuts should only be given in mashed form to infants and toddlers, because whole peanuts can be aspirated.

In two recent randomized trials, the risk of celiac disease was not reduced either by the delayed introduction of gluten (after the 6th month) or by its early introduction (before the 4th month) (36, 37).

Complementary feeding and food intolerance.

There is no evidence to support the notion that allergies can be prevented by delaying the intake of foods that commonly provoke allergic reactions, such as eggs, fish, or peanuts.

There is, however, an association between the consumption of large amounts of gluten when complementary feeding is introduced and a higher rate of celiac disease. It therefore seems reasonable to give only small amounts of gluten at first (one spoonful of cereal-based baby food, a few noodles) and to increase the amount gradually (e22).

All types of complementary food can be given as soon as complementary feeding is initiated, including the commonly allergenic foods. This also holds if the child has a family history of allergy or celiac disease.

Nutritional supplements in the first year

In Germany, healthy infants are given 2 mg of vitamin K by mouth three times in the first few weeks of life, generally at birth, at 7–10 days, and at 4–6 weeks of age. This effectively prevents hemorrhages due to vitamin K deficiency (38).

Infants should also be given tablets containing vitamin D (400–500 I.U./day) and fluoride (generally 0.25 mg/day) starting from the age of 5–10 days. Vitamin D administration is continued until the beginning of the child’s second summer, when increased exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays promotes endogenous synthesis. Fluoride administration is continued until the child is able to use fluoridated toothpaste regularly and to spit it out reliably (usually between the third and fourth birthdays) (39, e23). If the local drinking water contains more than 0.7 ppm of fluoride, additional fluoride administration is unnecessary; if the concentration is between 0.3 and 0.7 ppm, a reduced dose of fluoride is recommended.

Beverages

Healthy, exclusively breast-fed infants need nothing beyond mother’s milk to drink. Only after the introduction of three semisolid meals a day should they be given water or an appropriate kind of unsweetened tea to drink, preferably from a cup (3, e24).

Supplements in the first year.

In Germany, healthy infants are given 2 mg of vitamin K by mouth three times in the first few weeks of life, generally at birth, at 7–10 days, and at 4–6 weeks of age. This effectively prevents hemorrhages due to vitamin K deficiency.

Continuous sucking on a bottle of milk, sweetened tea, or fruit juice should definitely be avoided because of the high risk of caries in the front teeth (Figure 4); likewise, infants should not be given a “bedtime bottle.”

Figure 4.

Baby bottle caries. Reproduced from (e24), with permission

Unaltered cow’s milk should not be given as a beverage before the child’s second year of life, and should initially be given in small amounts only (about 200 mL per day*. Cow’s milk promotes iron deficiency; moreover, because of its high protein content, excessive intake of cow’s milk can promote obesity later in life (11, 19, e10, e11).

*In the German version of this manuscript mention was made of around 1/3 liter per day. The recommendation of 200 mL/ day cited here relates to the revised national guidelines published in September 2016.

Alternative nutrition in infancy

It is possible, in principle, for infants to be fed on a strictly ovo-lacto-vegetarian diet without any ill effect. Because of the attendant risks of inadequate nutrition, however, the foods must be chosen carefully and the child’s growth and iron status should be monitored by a physician.

If a meatless vegetable-potato-cereal mixture (Table 4) is given instead of a vegetable-potato-meat mixture (Figure 3), a similar intake of most nutrients and protein can be achieved, but there is a higher risk of deficiency of individual nutrients, such as iron, zinc, and DHA.

Table 4. Recipe for a vegetarian vegetable-potato-cereal mash, from (3). Alternatively, ready-made products can be given.

| Home-made vegetable-potato-cereal mash | |

|---|---|

| 90–100 g | Vegetables |

| 40–60 g | Potato |

| 30–45 g | Fruit juice |

| 10 g | Cereal |

| 8–10 g | Rapeseed oil |

The risks of a vegan diet for infants.

A strictly vegan diet for an infant, without any nutrient supplementation, puts the infant at high risk of nutritional deficiencies. In particular, inadequate vitamin B12 intake can cause irreversible neurological damage.

If a ready-made meatless baby food product contains no supplemental vitamin C, 2–3 tablespoons of vitamin-C-rich fruit juice or purée should be given as well to improve the bio-availability of vegetable-derived iron.

A strictly vegan diet for an infant, without any nutrient supplementation, puts the infant at high risk of nutritional deficiencies. In particular, inadequate vitamin B12 intake can cause irreversible neurological damage; this risk is also present in infants who are breast-fed by a vegan mother (40, e25). A vegan diet is also often low in DHA, vitamin D, iron, and zinc and is disadvantageous for the health and development of the child.

Overview

The health benefits of a balanced infant diet that is based on up-to-date scientific knowledge call to mind what Winston Churchill said in a BBC radio interview in 1943: “[T]here is no finer investment for any community than putting milk into babies. Healthy citizens are the greatest asset any country can have.” (e26).

Physicians can do much good by helping families implement healthful nutrition for their children. Useful aids for this purpose include the current scientifically based recommendations (3, 4), manufacturer-independent informational materials, media and apps for mobile devices (www.kindergesundheit.de/app.html), and free, accredited interactive CME modules (www.early-nutrition.org/en/enea/).

Further information.

Further information on CME.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

This CME unit can be accessed until 18 September 2016, and earlier CME units until the dates indicated:

“The Diagnosis and Treatment of Hair and Scalp Diseases” (Issue 21/2016) until 21 August 2016,

“Alcohol Dependence and Harmful Use of Alcohol” (Issue 17/2016) until 24 July 2016,

“Acute Lumbar Back Pain” (Issue 13/2016) until 27 June 2016

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

When can complementary feeding be introduced, at the earliest?

at the start of the 3rd month

at the start of the 4th month

at the start of the 5th month

at the start of the 6th month

at the start of the 7th month

Question 2

How long, at most, can freshly pumped mother’s milk be stored at room temperature before feeding?

1–2 hours

2–4 hours

4–6 hours

6–8 hours

8–10 hours

Question 3

How much (whole) cow’s milk should a child aged 12 to 23 months drink per day, at most?

50 mL

150 mL

300 mL

450 mL

600 mL

Question 4

What supplements should all four-month-old babies be given, regardless of their current diet?

vitamin D and vitamin B12

vitamin D and vitamin K

vitamin D and fluorine

fluorine and Iodine

fluorine and vitamin K

Question 5

What micronutrient is generally not adequately delivered to an exclusively breast-fed infant of a strictly vegan mother?

vitamin A

vitamin D

vitamin B6

vitamin B12

vitamin E

Question 6

When does an infant begin to need other fluids to drink besides mother’s milk or baby formula (such as water or unsweetened tea of an appropriate type approved for babies)?

from birth

from the first complementary feeding onward

as soon as he or she is taking complementary feeding three times a day

from the 12th month onward

from the 3rd month onward, if in the summer

Question 7

What should a mother be advised about the advantages and disadvantages of home-made versus commercial baby food for complementary feeding?

Home-made baby food is better.

Home-made baby food is more healthful.

Commercial baby food contains a larger quantity of harmful substances.

Commercial baby food is cheaper.

Home-made baby food enables a greater variety of tastes.

Question 8

A mother asks you for advice about what she can do in her child’s first year to prevent obesity in later life. What should you tell her?

There appears to be a causal link between the lower amount of weight gain seen in wholly breast-fed infants in their first year and a lower risk of obesity later on in life.

Drinking large amounts of whole milk along with complementary feeding is not associated with a higher risk of obesity.

If the infant is fed with baby formula, a low-protein, high-carbohydrate formula should be chosen.

Breast-fed infants weigh more than those fed with baby formula during the first year and therefore have a higher risk of obesity later on in life as well.

The addition of probiotic substances to mother’s milk has been shown to prevent obesity later on in life.

Question 9

What should parents be advised concerning alternatives to mother’s milk when they bring the child for the U2 checkup (second well-baby check-up, 3rd to 10th day of life)?

Mare’s milk can be given for infant milk feeding.

Children who are allergic to cow’s milk can be given goat’s milk instead.

Formulae for infant feeding can be made at home and do not need to be bought in a store.

Baby formula based on soybean protein should only be given on a physician’s advice in the first six months of life.

Baby formula based on soybean protein contains small quantities of protein from cow’s milk and should therefore not be given to infants who are allergic to cow’s milk.

Question 10

How should you advise a mother who tells you that her 8-month-old baby does not want to eat any vegetables?

Eating vegetables is unimportant at this age anyway.

As long as the child is eating enough fruit, vegetables can be dispensed with.

She should not give the child any more vegetables for the time being and try again after the child’s first birthday.

Vegetables that are at first rejected are often accepted if offered over and over again.

If she keeps on offering the child vegetables that have already been rejected on multiple occasions, this will only reinforce the rejection.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Koletzko has received reimbursement of travel and accommodation costs as well as honoraria for participating in continuing medical education events from the following manufacturers of nutritional products: Danone, DGC, Hochdorf, Med Johnson, and Nestlé. He has received support for a research project that he initiated from Abbott, Danone, and Nestlé. A member of the German National Breastfeeding Commission, he is an advocate of breastfeeding.

Dr. Prell has received lecture honoraria from the Hipp company.

References

- 1.Koletzko B, Brands B, Chourdakis M, et al. The power of programming and the early nutrition project: opportunities for health promotion by nutrition during the first thousand days of life and beyond. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64:141–150. doi: 10.1159/000365017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koletzko B, Brands B, Poston L, Godfrey K, Demmelmair H. Early Nutrition P: Early nutrition programming of long-term health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:371–378. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bührer C, Genzel-Boroviczény O, et al. Ernährungskommission der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinder und Jugendmedizin (DGKJ) Ernährung gesunder Säuglinge. Empfehlungen der Ernährungskommission der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2014;162:527–538. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koletzko B, Bauer CP, Brönstrup A, et al. Säuglingsernährung und Ernährung der stillenden Mutter. Aktualisierte Handlungsempfehlungen des Netzwerks Junge Familie, ein Projekt von IN FORM. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2013;161:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agostoni C, Braegger C, et al. ESPGHAN-Committee on Nutrition. Breast-feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:112–125. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819f1e05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agostoni C, Decsi T, et al. ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Complementary feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:99–110. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000304464.60788.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. A summary of the agency for healthcare research and quality’s evidence report on breastfeeding in developed countries. Breastfeed Med. 2009;(Suppl 1):17–13. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergison A, Dagan R, Arguedas A, et al. Otitis media and its consequences: beyond the earache. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:195–203. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen A, Rogan WJ. Breastfeeding and the risk of postneonatal death in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e435–e439. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gdalevich M, Mimouni D, David M, Mimouni M. Breast-feeding and the onset of atopic dermatitis in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:520–527. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horta BL, Victora CG. A systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013. Long-term effects of breastfeeding. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Remley DT. Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:525–535. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steer CD, Lattka E, Koletzko B, Golding J, Hibbeln JR. Maternal fatty acids in pregnancy, FADS polymorphisms, and child intelligence quotient at 8 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:1575–1582. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.051524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koletzko B, Boey CCM, Campoy C, et al. Current information and Asian perspectives on long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy, lactation and infancy. Systematic review and practice recommendations from an early nutrition academy workshop. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;65:i49–i80. doi: 10.1159/000365767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Victora CG, Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e199–e205. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360:187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebhan B, Kohlhuber M, Schwegler U, Koletzko B. Infant feeding practices and associated factors through the first 9 months of life in Bavaria, Germany. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:467–473. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819a4e1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lonnerdal B. Growth of breast-fed and formula-fed infants from 0 to 18 months: the DARLING Study. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1035–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan J, Liu L, Zhu Y, Huang G, Wang PP. The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agostoni C, Axelsson I, et al. ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Soy protein infant formulae and follow-on formulae: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:352–361. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189358.38427.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koletzko B, Carlson SE, van Goudoever JB. Should infant formula provide both omega-3 DHA and omega-6 arachidonic acid? Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66:137–138. doi: 10.1159/000377643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber M, Grote V, Closa-Monasterolo R, et al. Lower protein content in infant formula reduces BMI and obesity risk at school age: follow-up of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1041–1051. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.064071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osborn DA, Sinn JK. Prebiotics in infants for prevention of allergy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006474.pub3. Cd006474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborn DA, Sinn JK. Probiotics in infants for prevention of allergic disease and food hypersensitivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006474.pub2. Cd006475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Schulz H, et al. Allergic manifestation 15 years after early intervention with hydrolyzed formulas—the GINI Study. Allergy. 2016;71:210–219. doi: 10.1111/all.12790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedemann M. Epidemiology of invasive neonatal Cronobacter (Enterobacter sakazakii) infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1297–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0779-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.EFSA. Scientific opinion on the appropriate age for introduction of complementary feeding of infants. EFSA J. 2009;7 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier AS, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Leathwood PD, Issanchou SN. Breastfeeding and experience with variety early in weaning increase infants’ acceptance of new foods for up to two months. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:849–857. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coulthard H, Harris G, Emmett P. Delayed introduction of lumpy foods to children during the complementary feeding period affects child’s food acceptance and feeding at 7 years of age. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;5:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hilbig A, Alexy U, Kersting M. Beikost: Breimahlzeiten oder Finger Food? Ein Kommentar des FKE zum ‚Baby-led Weaning’. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2014;162:616–622. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexy U, Drossard C, Kersting M, Remer T. Iodine intake in the youngest: impact of commercial complementary food. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1368–1370. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Silva D, Geromi M, Halken S, et al. Primary prevention of food allergy in children and adults: systematic review. Allergy. 2014;69:581–589. doi: 10.1111/all.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nwaru BI, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, et al. Age at the introduction of solid foods during the first year and allergic sensitization at age 5 years. Pediatrics. 2010;125:50–59. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zutavern A, Brockow I, Schaaf B, et al. Timing of solid food introduction in relation to atopic dermatitis and atopic sensitization: results from a prospective birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:401–411. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muche-Borowski C, Kopp M, Reese I, et al. Allergy prevention. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:718–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vriezinga SL, Auricchio R, Bravi E, et al. Randomized feeding intervention in infants at high risk for celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1304–1315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, Francavilla R, et al. Introduction of gluten, HLA status, and the risk of celiac disease in children. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1295–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bührer C, Genzel-Boroviczény O, et al. Ernährungskommission der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinderheilkunde und Jugendmedizin. Vitamin-K-Prophylaxe bei Neugeborenen. Monatsschr Kinderheil. 2013;161:351–353. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koletzko B, Bergmann KS, Przyrembel H. Prophylaktische Fluoridgabe im Kindesalter. Empfehlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin und der Deutschen Akademie für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2013;161:508–509. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casella EB, Valente M, de Navarro JM, Kok F. Vitamin B12 deficiency in infancy as a cause of developmental regression. Brain Dev. 2005;27:592–594. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Koletzko B, Bhatia J, Bhutta Z. Koletzko B, et al. 2nd revised edition. Basel, Karger: World Rev Nutr Diet. Basel Karger; 2015. Pediatric Nutrition in Practice; 326 pp. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Koletzko B. (14th edition) Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2014. Kinder- und Jugendmedizin. [Google Scholar]

- e3.Domellof M, Braegger C, et al. ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Iron requirements of infants and toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:119–129. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Gastroenterologie und Ernährung (GPGE) Akute infektiöse Gastroenteritis. www.gpge.de/frameset.htm?/leitlinien.htm. (last accessed on 22 April 2016)

- e5.Vennemann M, Fischer D, Findeisen M. Kindstodinzidenz im internationalen Vergleich. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2003;151:510–513. [Google Scholar]

- e6.Gdalevich M, Mimouni D, Mimouni M. Breast-feeding and the risk of bronchial asthma in childhood: a systematic review with meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Pediatr. 2001;139:261–266. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Prugger C, Keil U. [Development of obesity in Germany—prevalence, determinants and perspectives] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007;132:892–897. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Riehm K, Schmutzler RK. Risikofaktoren und Prävention des Mammakarzinoms. Onkologe. 2015;21:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- e9.Empfehlung der Nationalen Stillkommission. Stillinformationen für Schwangere. www.bfr.bund.de/cm/350/stillempfehlungen-fuer-schwangere-deutsch.pdf. (last accessed on 22 April 2016)

- e10.Arenz S, Ruckerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R. Breast-feeding and childhood obesity—a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1247–1256. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, Yang M, Glazebrook CP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:1019–1026. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221–229. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825c9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Stillkommission N, Risikobewertung Bf. Sammlung Aufbewahrung und Umgang mit abgepumpter Muttermilch fuer das eigene Kind. www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/sammlung_aufbewahrung_und_umgang_mit_abgepumpter_muttermilch_fuer_das_eigene_kind.pdf. 1998 (last accessed on 22 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- e14.Böhles HJ, Daschner F, Fusch C, et al. Hinweise zur Zubereitung und Handhabung von Säuglingsnahrungen. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2004;152:318–320. [Google Scholar]

- e15.Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung. Empfehlungen zur hygienischen Zubereitung von pulverförmiger Säuglingsnahrung. www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/empfehlungen-zur-hygienischen-zubereitung-von-pulverfoermiger-saeuglingsnahrung.pdf. 2012. (last accessed on 22 April 2016)

- e16.Rapley G. Baby-led weaning: transitioning to solid foods at the baby’s own pace. Community Pract. 2011;84:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Townsend E, Pitchford NJ. Baby knows best? The impact of weaning style on food preferences and body mass index in early childhood in a case-controlled sample. BMJ open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000298. e000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Böhles HJ, Fusch C, et al. Ernährungskommission der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinderheilkunde und Jugendmedizin. Vermarktung von Beikostprodukten zur Flaschenfütterung. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2007;155:968–970. [Google Scholar]

- e19.Alm B, Aberg N, Erdes L, et al. Early introduction of fish decreases the risk of eczema in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:11–15. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.140418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Kull I, Bergstrom A, Lilja G, Pershagen G, Wickman M. Fish consumption during the first year of life and development of allergic diseases during childhood. Allergy. 2006;61:1009–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803–813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Namatovu F, Sandstrom O, Olsson C, Lindkvist M, Ivarsson A. Celiac disease risk varies between birth cohorts, generating hypotheses about causality: evidence from 36 years of population-based follow-up. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Empfehlungen der DAKJ zur Prävention der Milchzahnkaries. Empfehlungen zur Prävention der Milchzahnkaries. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkd. 2007;155:544–548. [Google Scholar]

- e24.Splieth CH, Treuner A, Berndt C. Orale Gesundheit im Kleinkindalter. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. 2009;4:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- e25.von Schenck U, Bender-Gotze C, Koletzko B. Persistence of neurological damage induced by dietary vitamin B-12 deficiency in infancy. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:137–139. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Churchill W. A four year plan for England. London: Broadcast over BBC, March; 21. Post-war councils on world problems; 1943 pp. [Google Scholar]