Abstract

MAP1S (originally named C19ORF5) is a widely distributed homolog of neuronal-specific MAP1A and MAP1B, and bridges autophagic components with microtubules and mitochondria to affect autophagosomal biogenesis and degradation. Mitochondrion-associated protein LRPPRC functions as an inhibitor for autophagy initiation to protect mitochondria from autophagy degradation. MAP1S and LRPPRC interact with each other and may collaboratively regulate autophagy although the underlying mechanism is yet unknown. Previously, we have reported that LRPPRC levels serve as a prognosis marker of patients with prostate adenocarcinomas (PCA), and that patients with high LRPPRC levels survive a shorter period after surgery than those with low levels of LRPPRC. MAP1S levels are elevated in diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocelular carcinomas in wildtype mice and the exposed MAP1S-deficient mice develop more malignant hepatocellular carcinomas. We performed immunochemical analysis to evaluate the co-relationship among the levels of MAP1S, LRPPRC, P62, and γ-H2AX. Samples were collected from wildtype and prostate-specific PTEN-deficient mice, 111 patients with PCA who had been followed up for 10 years and 38 patients with benign prostate hyperplasia enrolled in hospitals in Guangzhou, China. The levels of MAP1S were generally elevated so the MAP1S-mediated autophagy was activated in PCA developed in either PTEN-deficient mice or patients than their respective benign tumors. The MAP1S levels among patients with PCA vary dramatically, and patients with low MAP1S levels survive a shorter period than those with high MAP1S levels. Levels of MAP1S in collaboration with levels of LRPPRC can serve as markers for prognosis of prostate cancer patients.

Keywords: DNA double strand break, P62, PTEN, benign prostatic hyperplasia, overall survival, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian cells primarily use the autophagy system to degrade dysfunctional organelles, misfolded/aggregated proteins, and other macromolecules [1]. After autophagy is initiated, LC3 is converted to LC3-II [2]. The substrates of autophagy, including protein aggregates and dysfunctional organelles, are brought into autophagosomes through binding with the LC3-II-interactive substrate receptor P62 that is enriched in ubiquitin-positive Mallory–Denk bodies in the liver [3,4]. If the autophagy process is blocked before autophagosomal formation, the fragmented mitochondria will release cytochrome c and other small molecules to induce apoptosis [5–7]. If either the process is blocked before the autolysosomal formation or autophagosomes are not degraded efficiently, the accumulated mitochondria may become damaged by their own production of superoxide and start to leak electrons and lose their membrane potentials, and even further induce robust oxidative stress [8]. Reactive oxygen species cause telomere attrition and DNA double strand breakage [9,10] and simultaneously subvert mitotic checkpoints [11,12]. Therefore, genome instability is amplified through a cascade of autocatalytic karyotypic evolution through continuous cycles of chromosomal breakage–fusion–bridge and eventually leads to tumorigenesis [13–15].

MAP1S, a member of microtubule-associated protein 1 family and previously named as C19ORF5, was originally found to be an interactive partner of microtubule stabilizer and tumor suppressor RASSF1A and mitochondrion-associated autophagy inhibitor LRPPRC [16–21]. Similar to its homolog MAP1A and MAP1B, MAP1S interacts with both LC3-I and LC3-II isoforms [2,22–24]. Overexpression of a short form of MAP1S causes mitochondrial aggregation and DNA degradation [18]. MAP1S was recently identified as a positive regulator of autophagy and its depletion led to autophagy defects under nutritive stress and accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria [24]. Normal hepatocytes express low levels of MAP1S. When they are exposed to chemical carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN), their levels of MAP1S are dramatically elevated to activate autophagy to remove P62-associated protein aggregates and dysfunctional mitochondria, reduce γ-H2AX-labeled DNA double-strand breaks (DSB), and suppress genome instability. Later, the total levels of MAP1S in the exposed hepatocytes become diminished. When hepatocytes with genome instability form tumor foci, cells in the foci are subjected to genome instability-induced metabolic stresses and their MAP1S levels are dramatically elevated again to activate autophagy. The early accumulation of an unstable genome enhances the probability of generating more tumor foci. After tumorigenesis, tumor development then triggers the activation of autophagy to reduce genome instability in tumor foci so that the tumor malignancy is reduced. MAP1S-deficient mice exhibit higher levels of P62 and genome instability and develop more tumor foci and more malignant hepatocellular carcinomas [25]. We concluded that an increase in MAP1S levels triggers autophagy to suppress genome instability so that both the incidence of DEN-induced onset of hepatocarcinomas and malignant progression are suppressed. Thus, a link between MAP1S-enhanced autophagy and suppression of genomic instability and tumorigenesis has been established.

Based on the somatic mutation data of 17301 genes from 316 ovarian cancer patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas, mutations in MAP1S were found to significantly reduce the survival of patients [26]. We previously reported that levels of the MAP1S-interactive protein LRPPRC are closely associated with poor prognosis of human prostate adenocarcinomas (PCA), and patients with higher levels of LRPPRC in PCA survive a shorter time [27]. The gene for autophagy regulator Phosphatase and tensin homolog PTEN was found to be mutated in human primary prostate cancer [28,29]. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine PTEN tumor suppressor gene has led to the establishment of a well-known mouse model mimicking human prostate cancer [30]. It is suggested that autophagy regulatory proteins play specific roles in the development of PCA.

In this study, we detected that levels of MAP1S, LRPPRC, P62, and γ-H2AX-labeled DNA DSB and genome instability were increased from prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) to PCA developed in PTEN-deficient mice, and that they were similarly increased from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) to PCA in patients. Therefore, a similar mechanism of tumor suppression through MAP1S-mediated autophagy may occur in PTEN-deficiency-induced PCA in mice and naturally grown PCA in patients. However, MAP1S-mediated autophagy activity was complicated. Similar to MAP1S-deficiency in mouse hepatocellular carcinomas, MAP1S levels in PCa patients were significantly correlated to overall survival. Patients with high levels of MAP1S survived for a longer period while patients with low levels of MAP1S exhibited poor prognosis. Higher levels of oxidative stress and genome instability enhanced the expression of MAP1S and activated autophagy to suppress oxidative stress and genome instability. Because of such a feedback regulatory loop, P62 and γ-H2AX lost their values as prognosis markers. The MAP1S levels were negatively correlated to LRPPRC levels while high levels of LRPPRC predicted poor prognosis and short survival. Both MAP1S levels and LRPPRC levels served as good markers for the prognosis of prostate cancer patients. Further decrease of MAP1S levels in patients with high LRPPRC levels led to shorter survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of PTEN−/− Mice and Collection of Prostate Tissue Samples

Ptenf/f mice were reported previously [30] and obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). ARR2PBi-Cre (Pb-Cre) mice were described previously [31]. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Texas A&M Health Science Center at Houston. Prostate tissue samples were collected in the same way as described [27].

Immunoblot Analyses and Fluorescent Confocal Microscopy

Prostate tissue samples were prepared for immunoblot analyses or fluorescent confocal microscopy as described before [27]. Antibody against MAP1S (Cat# AG10006) was a gift from Precision Antibody™, A&G Pharmaceutical, Inc. Antibodies against LRPPRC (Cat# sc-166178, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), P62 (Cat # BML-PW9860), γ-H2AX (rabbit polyclonal, A300-081A), and β-actin (SC-47778) were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences International Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA), Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. (Montgomery, TX), and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., respectively.

Enrollment of Patients, Collection of Human Tissue Samples and Immunohistochemistry Analysis

The same set of samples collected during 1999–2003 as described for LRPPRC analysis [27] was further used for immunohistochemistry analyses of MAP1S, P62, and γ-H2AX. Only one patient with PCA was excluded from the analyses because the data set was not complete. The histological scores were assigned by two independent clinical pathologists in a double-blind manner as described [27].

Semiquantitative Analysis and Statistical Analysis

Immunostaining results were presented as percentage of positively stained tumor cells and staining intensity similarly as described [32]. The percentage of positive cells was scored as 0 if no cell was stained, 1 if 1–10% cells were stained, 2 if 11–50% cells were stained, 3 if 51–80% cells were stained and 4 if >80% cells were stained. The staining intensity was scored as 0 if not being stained, 1 if being weakly stained, 2 if being moderately stained, and 3 if being strongly stained. Both percentage of positive cells and staining intensity were decided in a double-blind manner. The scores for intensity and frequency of each protein was added (0–7) and presented as high (≥4) or low level (<4). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to reveal an association between the intensity, frequency, and levels of MAP1S and the stages of prostate disease BPH and PCa [33]. Overall survival was measured from the initiation of treatment until the end of the observation period and analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to evaluate statistically significant differences between groups. P values were the probabilities larger than the calculated χ2 values. Cox proportional hazards analysis using a univariate or multivariate method was used to explore the effect of variables on overall survival. SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses and a P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

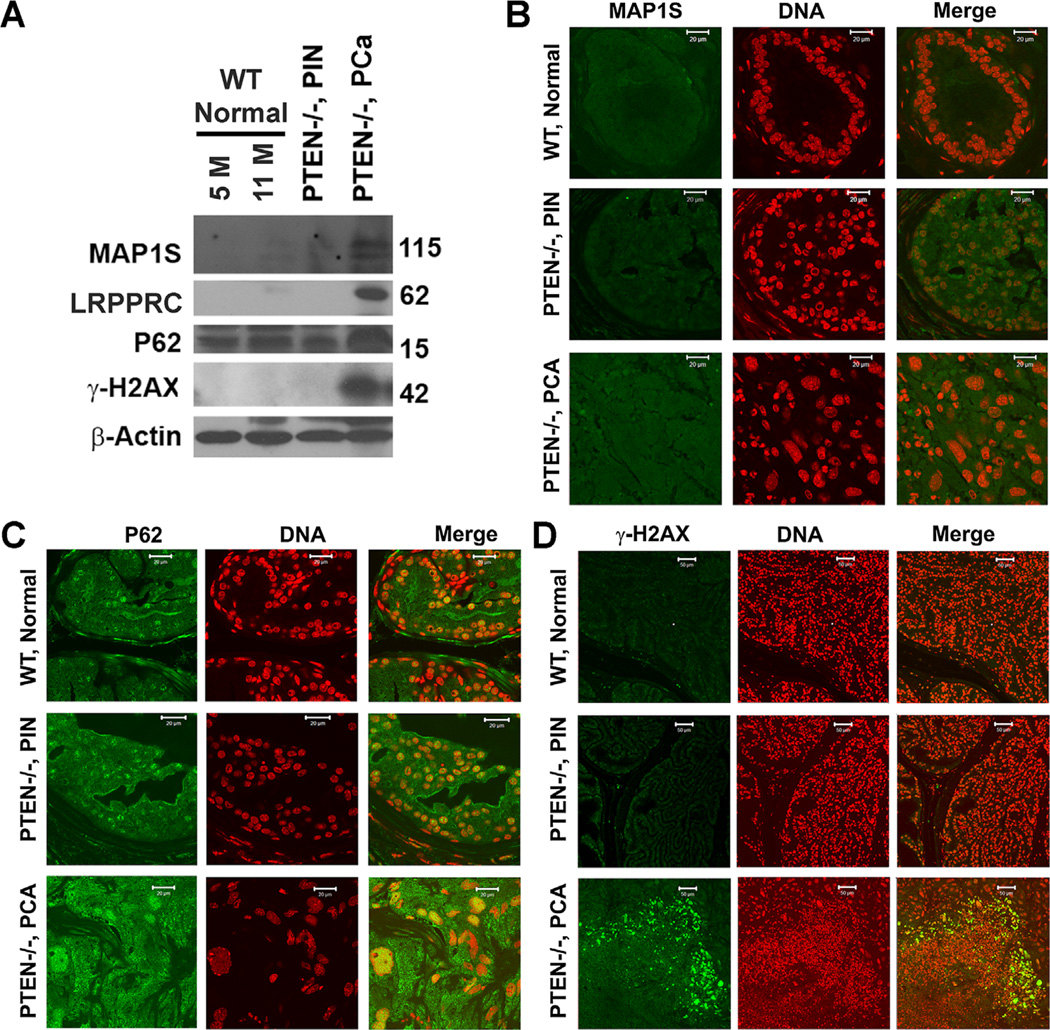

The Levels of MAP1S Are Elevated in Prostate Adenocarcinomas Developed in Mice Carrying Prostate-Specific PTEN Deletion

Similar to the LRPPRC levels reported before [27], the levels of MAP1S were very low in both normal prostate tissues of wildtype mice of different ages and PIN developed in prostate-specific PTEN knockout mice. But the levels of MAP1S were dramatically elevated in PCA developed in the PTEN knockout mice (Figure 1A,B). The differences in P62 levels among the wildtype normal prostate tissues, PIN and PCA in PTEN-deficient mice were not as dramatic as those in MAP1S levels (Figure 1A,C). The p62 signals in both normal tissues and PIN were mainly distributed in nuclei while those in PCA were distributed obviously in cytoplasm (Figure 1C). High levels of cytosolic P62 in PCA was correlated with high levels of γ-H2AX-associated DNA double strand breakage (Figure 1A,D). The variable sizes of nuclei in the tissues of PCA were possibly caused by the genome instability-representative aneuploidy and/or genome instability-inducing polyploidy (Figure 1). Therefore, the levels of MAP1S were elevated during the development of PCA in prostate-specific PTEN-deficient mice similarly to hepatocellular carcinomas in DEN-induced mice.

Figure 1.

The levels of MAP1S are enhanced in prostate adenocarcinomas developed in mice carrying prostate-specific PTEN deletion. (A) Immunobot analyses of prostate tissues with antibody against MAP1S, LRPPRC, P62, γ-H2Ax, or β-actin. Same amount of total proteins was loaded to each lane and β-actin served as another loading control. (B–D) Fluorescent immunostaining of prostate tissue sections with antibody specific to MAP1S (B), P62 (C), or γ-H2AX (D). Prostate tissues were collected from 5 or 11-month-old wildtype mice (WT, Normal), tissues with prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PTEN−/−, PIN) or prostate adenocarcinomas were from 11-month-old prostate-specific PTEN knockout mice (PTEN−/−, PCA).

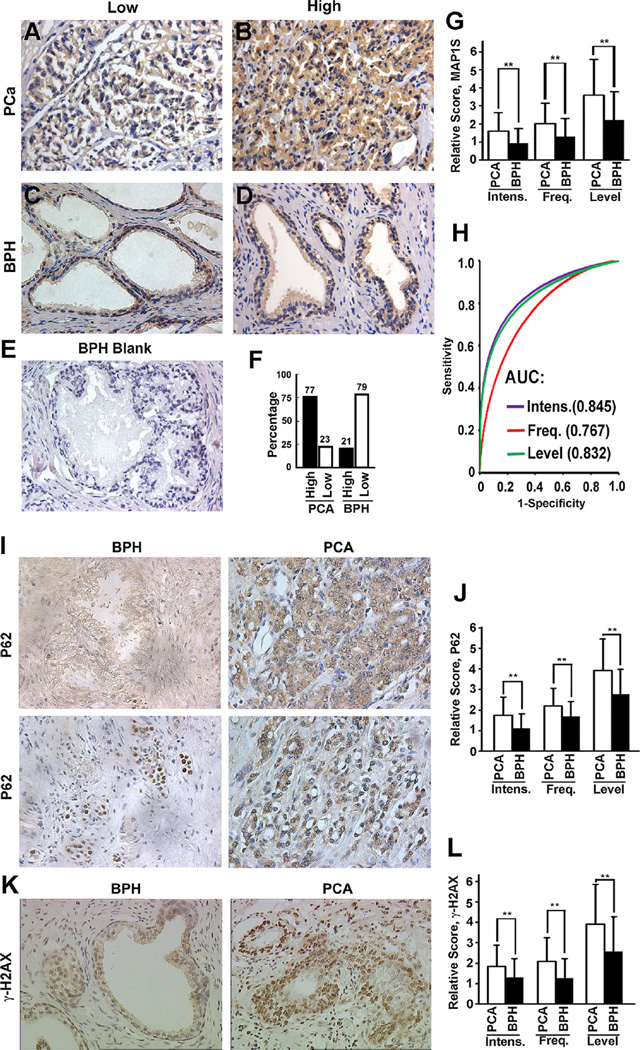

The Levels of MAP1S Are Higher in PCA Patients Than in Patients Suffering From Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Although we observed similar trends between liver and prostate of mice, the significance of MAP1S levels in human PCA was still unknown. Immunohistochemistry analyses were performed with the same standards by technicians in a pathology laboratory on tissue sections from 111 patients suffering from prostate adenocarcinoma and 38 patients suffering from BPH (Table 1). We found that MAP1S was mainly expressed in the cytoplasm of the luminal and psudostratified epithelial cells of prostate glands in patients with BPH or PCA at different stages (Figure 2A–D). With the population of luminal epithelial cells expanded in PCA, the number of cells expressing MAP1S naturally increased, but the intensities of MAP1S in the luminal epithelial cells were also significantly elevated (Figure 2F,G and Table 1). The area under the ROC curve was 0.845, 0.767, and 0.832 for the intensity, frequency and levels of MAP1S, respectively (Figure 2H).

Table 1.

The Clinical Features of Patients With PCa and Levels of MAP1S-Related Proteins

| Clinical features |

No. of case |

MAP1S | P62 | γ-H2AX | LRPPRC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X ± SD | P | X ± SD | P | X ± SD | P | X ± SD | P | ||

| Tissue type | |||||||||

| PCa | 111 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | <0.001 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | 4.6 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| BPH | 38 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <70 | 49 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 0.914 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 0.639 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 0.775 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 0.555 |

| ≥70 | 62 | 4.4 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Gleason score | |||||||||

| <8 | 90 | 4.7 ± 1.4 | <0.001 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 0.077 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 0.094 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 0.011 |

| ≥8 | 22 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 1.7 | ||||

| Preoperative PSA | |||||||||

| <10 ng/ml | 41 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 0.003 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 0.867 | 4.9 ± 1.3 | 0.559 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 0.023 |

| ≥10 ng/ml | 70 | 4.1 ± 1.7 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||||

| I/II | 61 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 0.025 | 4.6 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| III | 50 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 58 | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 0.003 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 0.006 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | <0.001 | 3.9 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 53 | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | ||||

| HTSin2 | |||||||||

| Yes | 101 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 0.058 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 0.070 | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 0.117 |

| No | 10 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 1.5 | ||||

| HTSaf2 | |||||||||

| Yes | 62 | 5.0 ± 1.4 | <0.001 | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 0.097 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 0.064 | 3.9 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| No | 49 | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 1.2 | ||||

| Survival time | |||||||||

| ≥5 years | 60 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 0.034 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 0.092 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| <5 years | 51 | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | ||||

| Survival time | |||||||||

| ≥10 years | 29 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | <0.001 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 0.245 | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 0.007 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| <10 years | 82 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 5.1 ± 1.3 | ||||

HTSin2, hormone therapy sensitivity within 2 years; HTSaf2, hormone therapy sensitivity after 2 years.

Figure 2.

The levels of MAP1S, P62, and γ-H2AX are elevated in majority of patients with prostate adenocarcinomas. (A,B) Representative images (400×) of immunohistochemistry analyses of low (A) or high MAP1S expression in prostate adenocarcinomas (PCA) (B). (C,D) Representative images (400×) of immunohistochemistry analyses of low (C) or high MAP1S expression in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (D). (E) A BPH sample not stained with antibody against MAP1S shown as a negative control. (F,G) Quantitation of high or low expression levels of MAP1S in prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia. Bars represent the percentage of patients with high or low levels of MAP1S (F) or relative score of MAP1S intensity (Intens.), frequency (Freq.), and level between PCA and BPH. H. Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) showing the ability of the intensity, frequency and levels of MAP1S to predict stages of prostate disease BPH and PCa. AUC, area under the ROC curve. (I) Representative images (400×) of immunohistochemistry analyses of p62 level and distribution in BPH and PCA. (J) Comparison of the P62 intensity, frequency and level between BPH and PCa. (K) Representative images (400×) of immunohistochemistry analyses of γ-H2AX level and distribution in BPH and PCA. (L) Comparison of the γ-H2AX intensity, frequency, and level between BPH and PCa. Data in (G) and (J) and here are mean and standard deviation and differences are tested with Student's t-test. **P ≤ 0.01.

In the majority of luminal cells of patients with BPH, weak P62 signals diffused in the cytoplasm (Figure 2I). Similar to normal prostate tissues of wildtype mice and the PIN developed in PTEN−/− mice, some luminal cells in human BPH exhibiting intensive P62 signals had P62 distributed exclusively in nuclei (Figure 2I). Similar to PCA developed in PTEN knockout mice, human PCA exhibited significantly higher intensity and frequency of P62-positive cells (Figure 2J and Table 1). Unlike the exclusive distribution of high intensities of p62 in BPH in nuclei, the distribution of p62 was in the entire cells including cytoplasm and nucleus or perinuclear regions in PCA (Figure 2I).

Although the significance of nucleus-distributed p62 is still unknown, elevation of p62 in cytoplasm has been reported in human PCA [34]. High levels of cytosolic p62 indicate high levels of oxidative stress and genome instability [15]. Indeed, the genome instability indicator, the γ-H2AX level, in PCA was higher than in BPH (Figure 2K,L and Table 1). The background weak signals of γ-H2AX were distributed in both nucleus and cytoplasm of luminal cells in BPH, while the enhanced levels of γ-H2AX mainly appeared in the nuclei of PCA (Figure 2K). The enhanced levels of MAP1S, P62, and γ-H2AX in the general population of PCA patients indicate that autophagy activity is elevated during tumorigenesis.

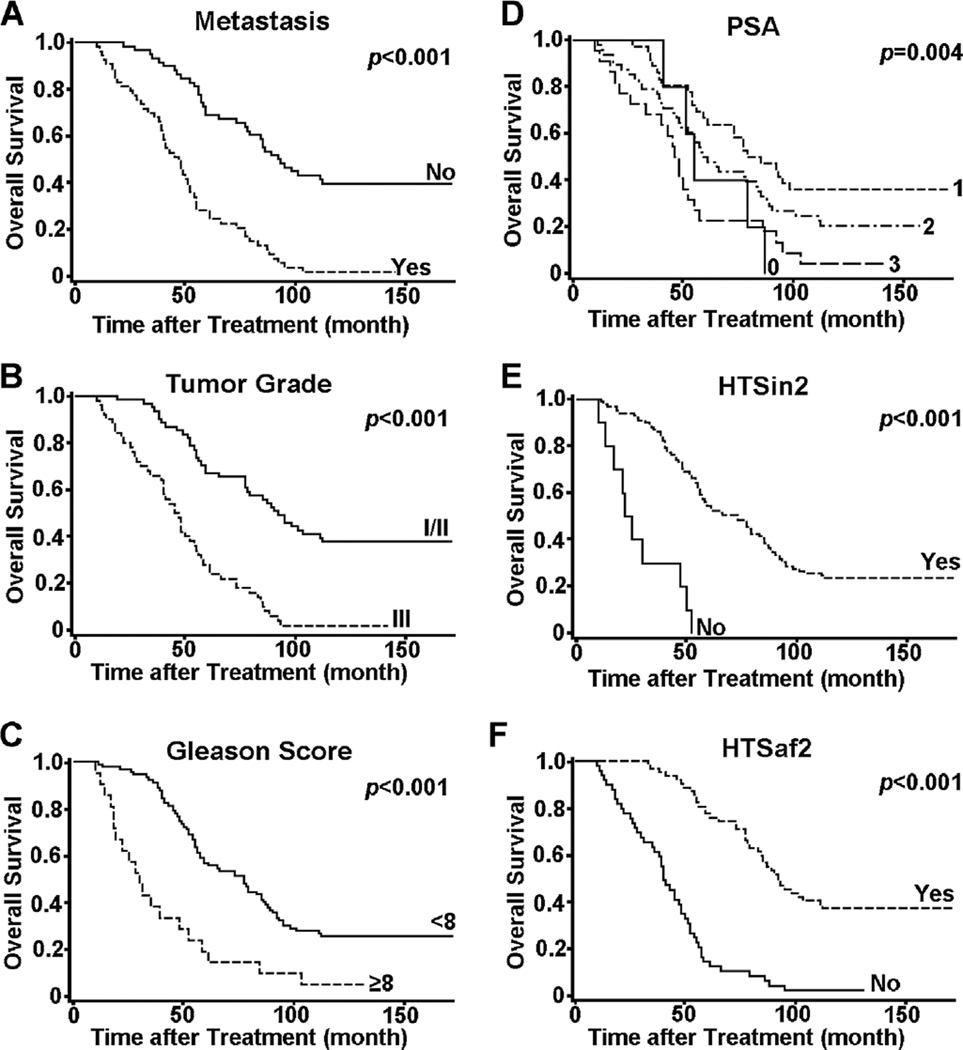

PCa Patients With Poor Prognosis Exhibit Low MAP1S Levels

Several clinical features recorded for our patient samples exhibited significant prognosis values for the overall survival of PCa patients after surgery. Patients who were in metastasis, who had high tumor grade, Gleason score or PSA, who did not respond to hormone therapy within 2 years, or who did not respond to hormone therapy after 2 years, usually had significantly reduced survival times after surgery (Figure 3). The levels of P62, γ-H2AX, and LRPPRC were higher in PCa patients who had higher Gleason score, PSA levels, or tumor grade, who were in metastasis, who did not respond to hormone therapy within 2 years or after 2 years of surgery, or who had shorter survival time. In contrast, MAP1S exhibited lower levels in those categories (Table 1). The values for MAP1S intensity, frequency, and levels were significantly and negatively correlated with the values for LRPPRC intensity, frequency, and level. The correlation coefficients of clinic features with MAP1S were opposite to those with LRPPRC (Table 2). Thus, PCa patients with worse clinical features exhibited lower levels of MAP1S and high levels of LRPPRC.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing the overall survival time after treatment of PCa patients being (Yes) or not being (No) in metastasis (A), with different tumor grade (B), Gleason score (C) or PSA levels (D), or showing (yes) or not showing (No) hormone therapy sensitivity within (E) or after 2 years (F). The significance of difference between two groups was estimated by log-rank test and p value for each plot was the probability larger than the χ2 value and shown on upper right corner.

Table 2.

The Correlation Coefficient (r) Between Different Measurements of Proteins and Other Clinical Features in PCA Patients

| MAP1S | LRPPRC | P62 | γ-H2AX | Gleason score |

Tumor grade |

Metastasis | PSA | HTSin2 | HTSaf2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inten | Freq | Level | Inten | Freq | Level | Inten | Freq | Level | Inten | Freq | Level | |||||||

| MAP1S | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intensity | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| Frequency | 0.53 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| <0.01 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Level | 0.86 | 0.89 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||||||||||

| LRPPRC | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intensity | −0.33 | −0.32 | −0.37 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||||||

| Frequency | −0.23 | −0.38 | −0.35 | 0.42 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||||||||

| Level | −0.33 | −0.41 | −0.43 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||||

| P62 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intensity | 0.07 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||

| Frequency | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.24 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Level | 0.10 | −0.11 | −0.01 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||||

| γ-H2AX | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intensity | 0.04 | −0.21 | −0.11 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.02 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||

| Frequency | −0.16 | −0.27 | −0.25 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 0.10 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Level | −0.03 | −0.21 | −0.15 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.13 | <0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Gleason score | −0.19 | −0.34 | −0.31 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 1.00 | |||||

| 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Tumor grade | −0.40 | −0.40 | −0.46 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 1.00 | ||||

| <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Metastasis | −0.26 | −0.24 | −0.29 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 1.00 | |||

| <0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.27 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.02 | <0.01 | |||||

| PSA | −0.20 | −0.28 | −0.27 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.19 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 1.00 | ||

| 0.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.71 | <0.01 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.13 | ||||

| HTSin2 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.36 | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.07 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.05 | −0.29 | −0.17 | −0.25 | −0.35 | −0.27 | −0.28 | 1.00 | |

| <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.58 | <0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||

| HTSaf2 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.51 | −0.52 | −0.48 | −0.59 | −0.08 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.10 | −0.20 | −0.18 | −0.36 | −0.51 | −0.46 | −0.31 | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.06 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

Data shown on top of each cells are the Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and bottom the probabilities (P). Highlighted cells are those with P ≤ 0.05. HTSin2, hormone therapy sensitivity within 2 years; HTSaf2, hormone therapy sensitivity after 2 years.

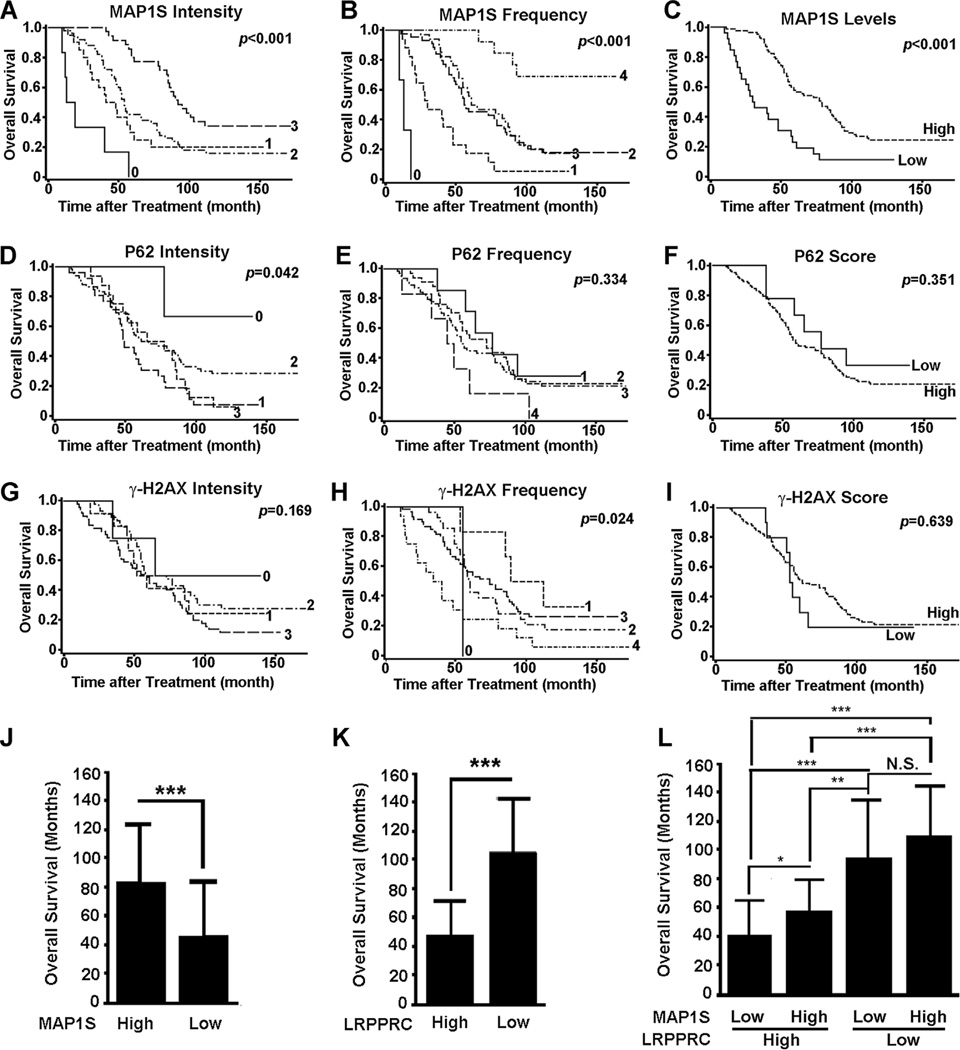

Low Levels of MAP1S and High Levels of LRPPRC Predict Short Overall Survival After Treatment for PCa Patients

Although the indices for P62 and γ-H2AX behaved poorly as prognosis markers, MAP1S intensity and frequency were significantly and positively correlated to overall survival and exhibited hazard ratios significantly smaller than 1 (Figure 4A–I and Table 3). Combining intensity and frequency into one single index, MAP1S levels served as a better predictor of overall survival than intensity and frequency alone and patients with higher MAP1S levels survived a longer period (Figure 3C,J). The intensity, frequency or level of MAP1S or LRPPRC, metastasis, tumor grade, Gleason score, PSA, hormone therapy sensitivity within or after 2 years of surgery was all significantly correlated with overall survival individually based on univariate analyses, but both MAP1S level and LRPPRC level were the best based on multivariate analysis (Table 3). In contrast, patients with higher levels of LRPPRC survived a shorter period (Figure 4K) [27]. When we combined MAP1S levels and LRPPRC levels together to analyze the survival data, we found that lower levels of MAP1S had not significantly impacted the survival of patients with low levels of LRPPRC but significantly further reduced the overall survival of patients with high levels of LRPPRC (Figure 4K). Therefore, MAP1S levels and LRPPRC levels in combination should be used as indexes to predict prognosis of PCa patients after surgery, especially of the subpopulation of PCa patients with high levels of LRPPRC.

Figure 4.

Survival analyses of MAP1S-mediated autophagy markers in PCA patients. (A–I) The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing the overall survival time after treatment of PCa patients with different MAP1S intensity (A), frequency (B), or level (C), P62 intensity (D), frequency (E), or level (F), or γ-H2AX intensity (G), frequency (H), or level (I). The significance of difference between two groups was estimated by log-rank test and P-value for each plot was the probability larger than the χ2 value and shown on upper right corner. (J–L) Comparison of overall survival times of PCa patients between high and low MAP1S levels (J) or LRPPRC levels (K) or among different groups of high or low MAP1S and LRPPRC levels (L). Data are mean and standard deviation and differences are tested with Student's t-test. N.S., not significant. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

Table 3.

Univariate or Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Ratios for Overall Survival Time

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| MAP1S intensity | 0.55 (0.42–0.71) | <0.01 |

| MAP1S frequency | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | <0.01 |

| MAP1S level | 0.39 (0.24–0.63) | <0.01 |

| LRPPRC intensity | 2.69 (1.97–3.65) | <0.01 |

| LRPPRC frequency | 2.76 (2.08–3.66) | <0.01 |

| LRPPRC level | 7.11 (3.60–14.0) | <0.01 |

| P62 intensity | 1.33 (0.97–1.83) | 0.08 |

| P62 frequency | 1.27 (0.92–1.74) | 0.15 |

| P62 level | 1.48 (0.64–3.39) | 0.36 |

| γ-H2AX intensity | 1.31 (0.98–1.76) | 0.07 |

| γ-H2AX frequency | 1.29 (0.96–1.73) | 0.09 |

| γ-H2AX level | 0.84 (0.41–1.74) | 0.64 |

| Gleason score | 3.14 (1.89–5.22) | <0.01 |

| Tumor grade | 4.03 (2.55–6.34) | <0.01 |

| Metastasis | 4.05 (2.56–6.37) | <0.01 |

| PSA | 1.45 (1.10–1.92) | <0.01 |

| HTSin2 | 0.15 (0.07–0.30) | <0.01 |

| HTSaf2 | 0.18 (0.12–0.29) | <0.01 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| MAP1S level | 0.47 (0.26–0.85) | 0.01 |

| LRPPRC level | 5.26 (2.45–11.3) | <0.01 |

| P62 level | 1.22 (0.47–3.13) | 0.69 |

| γ-H2AX level | 0.58 (0.25–1.32) | 0.19 |

| Gleason score | 2.52 (1.44–4.40) | <0.01 |

| Tumor grade | 1.68 (0.94–3.00) | 0.08 |

| Metastasis | 2.21 (1.31–3.71) | <0.01 |

| PSA | 1.10 (0.81–1.49) | 0.56 |

| HTSin2 | 0.51 (0.23–1.14) | 0.10 |

| HTSaf2 | 0.53 (0.30–0.92) | 0.02 |

HTSin2, hormone therapy sensitivity within 2 years; HTSaf2, hormone therapy sensitivity after 2 years.

DISCUSSION

Autophagy has drawn wide attention in recent years but its role in tumorigenesis seems controversial [35]. Based on our results, autophagy is a prosurvival mechanism to counteract oxidative stresses induced by environmental carcinogens in normal tissues or metabolic stress imposed by genome instability in tumor foci, and generally plays suppressive roles in the initiation and development of hepatocellular carcinomas [15,25]. MAP1S positively regulates autophagy to remove P62-associated ubiquitin-positive protein aggresomes or dysfunctional mitochondria and maintain genome stability, and its depletion causes autophagy defects and the accumulation of P62-associated protein debris and DNA double strand breaks [24,25]. The event of DNA double strand breakage initiates the cascade of chromosomal breakage–fusion–bridge cycles and results in genome instability, the origin of most types of solid tumors [13–15]. Therefore, experimental data generated from mouse model of hepatocellular carcinomas indicates that MAP1S-mediated autophagy suppresses the onset and development of liver cancer.

Since it is a consensus that genome instability as the origin of tumorigenesis is similar in different organs of different species, we started to examine the role of MAP1S-mediated autophagy in the development of PCA. Prostate-specific PTEN-deficient mice develop PIN and PCA spontaneously and have been widely adopted as research model of human PCA [30]. Levels of MAP1S, P62, and γ-H2AX in PTEN deficiency-triggered PCA are similarly elevated as in DEN-induced hepatocellular carcinomas, suggesting a general mechanism underlying tumorigenesis in both liver and prostate. Data from animal models of different types of cancers fit well with each other, which encourages us to examine the parameters in patients. Consistent with results from PTEN-deficient mice, human PCA, in general, also exhibit higher levels of MAP1S, P62, and γ-H2AX than the age-matched control BPH. Therefore, autophagy is activated to suppress oxidative stress and genome instability during the initial stage of development of PCA.

Late stages of tumors exhibiting high levels of genome instability will cause high levels of oxidative stress that requires high levels of MAP1S-mediated autophagy activity to suppress. Patients with high levels of MAP1S-mediated autophagy activity are supposed to have low levels of oxidative stress and genome instability. The levels of related markers in individual tumor focus only represent the final outcome of tumor development in this individual focus. LRPPRC functions as an inhibitor of autophagy and mitophagy but MAP1S acts as an activator of autophagy and mitophagy, although both interact with each other [20,24,25,36]. Among different PCa stages, patients at late PCa stages exhibit higher levels of LRPPRC, P62, and γ-H2AX, but lower levels of MAP1S than those at early stages do. Patients with higher MAP1S levels and lower LRPPRC levels survive a longer period than those with low MAP1S levels and higher LRPPRC levels. Under multivariate Cox analyses, the Hazard ratios for both MAP1S and LRPPRC levels surpassed those for traditional clinical features such as Gleason score, tumor grade, metastasis, PSA, and hormone therapy sensitivity, suggesting that LRPPRC levels and MAP1S levels, individually and in combination, may serve as promising prognosis markers for patients’ overall survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joe Corvera (A&G Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Columbia, MD) for anti-MAP1S mouse monoclonal antibody 4G1. This work was supported by DOD New Investigator Award W81XWH and NCI R01CA142862 to Leyuan Liu; China National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists grant no. 81101947 and The Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation grant no. 10151008901000070 to Hai Huang.

Abbreviations

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- DSB

double-strand breaks

- PCA

prostate adenocarcinomas

- PIN

prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- ROC

receiver operator characteristic

REFERENCES

- 1.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Pankiv S, Overvatn A, Brech A, Johansen T. Monitoring autophagic degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:181–197. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desagher S, Martinou JC. Mitochondria as the central control point of apoptosis. Trend Cell Biol. 2000;10:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suen YK, Fung KP, Choy YM, Lee CY, Chan CW, Kong SK. Concanavalin A induced apoptosis in murine macrophage PU5-1.8 cells through clustering of mitochondria and release of cytochrome c. Apoptosis. 2000;5:369–377. doi: 10.1023/a:1009691727077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas WD, Zhang XD, Franco AV, Nguyen T, Hersey P. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis of melanoma is associated with changes in mitochondrial membrane potential and perinuclear clustering of mitochondria. J Immunol. 2000;165:5612–5620. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, et al. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1025–1040. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Trimarchi JR, Smith PJ, Keefe DL. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to telomere attrition and genomic instability. Aging Cell. 2002;1:40–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra PK, Raghuram GV, Panwar H, Jain D, Pandey H, Maudar KK. Mitochondrial oxidative stress elicits chromosomal instability after exposure to isocyanates in human kidney epithelial cells. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:718–728. doi: 10.1080/10715760903037699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Angiolella V, Santarpia C, Grieco D. Oxidative stress overrides the spindle checkpoint. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:576–579. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Fang X, Baker DJ, et al. The ATM-p53 pathway suppresses aneuploidy-induced tumorigenesis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14188–14193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005960107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClintock B. The fusion of broken ends of chromosomes following nuclear fusion. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1942;28:458–463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.28.11.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duesberg P, Rasnick D. Aneuploidy, the somatic mutation that makes cancer a species of its own. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2000;47:81–107. doi: 10.1002/1097-0169(200010)47:2<81::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L, McKeehan WL, Wang F, Xie R. MAP1S enhances autophagy to suppress tumorigenesis. Autophagy. 2012;8:278–280. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.2.18939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, McKeehan WL. Sequence analysis of LRPPRC and its SEC1 domain interaction partners suggest roles in cytoskeletal organization, vesicular trafficking, nucleocytosolic shuttling and chromosome activity. Genomics. 2002;79:124–136. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mootha VK, Lepage P, Miller K, et al. Identification of a gene causing human cytochrome c oxidase deficiency by integrative genomics. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:605–610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242716699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Vo A, Liu G, McKeehan WL. Distinct structural domains within C19ORF5 support association with stabilized microtubules and mitochondrial aggregation and genome destruction. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4191–4201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Vo A, McKeehan WL. Specificity of the methylation-suppressed A isoform of candidate tumor suppressor RASSF1 for microtubule hyperstabilization is determined by cell death inducer C19ORF5. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1830–1838. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zou J, Yue F, Jiang X, Li W, Yi J, Liu L. Mitochondrion-associated protein LRPPRC suppresses the initiation of basal levels of autophagy via enhancing Bcl-2 stability. Biochem J. 2013;454:447–457. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou J, Yue F, Li W, et al. Autophagy inhibitor LRPPRC suppresses mitophagy through interaction with mitophagy initiator Parkin. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann SS, Hammarback JA. Molecular characterization of light chain 3. A microtubule binding subunit of MAP1A and MAP1B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11492–11497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoenfeld TA, McKerracher L, Obar R, Vallee RB. MAP 1A and MAP 1B are structurally related microtubule associated proteins with distinct developmental patterns in the CNS. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1712–1730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01712.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie R, Nguyen S, McKeehan K, Wang F, McKeehan WL, Liu L. Microtubule-associated protein 1S (MAP1S) bridges autophagic components with microtubules and mitochondria to affect autophagosomal biogenesis and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10367–10377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie R, Wang F, McKeehan WL, Liu L. Autophagy enhanced by microtubule- and mitochondrion-associated MAP1S suppresses genome instability and hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7537–7546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandin F, Clay P, Upfal E, Raphael BJ. Discovery of mutated subnetworks associated with clinical data in cancer. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2012;2012:55–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang X, Li X, Huang H, et al. Elevated levels of mitochondrion-associated autophagy inhibitor LRPPRC are associated with poor prognosis of human patients with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1228–1236. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cairns P, Okami K, Halachmi S, et al. Frequent inactivation of PTEN/MMAC1 in primary prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4997–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin C, McKeehan K, Wang F. Transgenic mouse with high Cre recombinase activity in all prostate lobes, seminal vesicle, and ductus deferens. Prostate. 2003;57:160–164. doi: 10.1002/pros.10283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding Y, Chen B, Wang S, et al. Overexpression of Tiam1 in hepatocellular carcinomas predicts poor prognosis of HCC patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:653–658. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eng J. ROC analysis: Web-based calculator for ROC curves. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2014. http://wwwjrocfitorg. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura H, Torigoe T, Asanuma H, et al. Cytosolic over-expression of p62 sequestosome 1 in neoplastic prostate tissue. Histopathol. 2006;48:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Vo A, Liu G, McKeehan WL. Putative tumor suppressor RASSF1 interactive protein and cell death inducer C19ORF5 is a DNA binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]