Summary

p97 is a AAA-ATPase with multiple cellular functions, one of which is critical regulation of protein homeostasis pathways. We describe the characterization of CB-5083, a potent, selective and orally bioavailable inhibitor of p97. Treatment of tumor cells with CB-5083 leads to accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins, retention of endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation (ERAD) substrates and generation of irresolvable proteotoxic stress leading to activation of the apoptotic arm of the unfolded protein response (UPR). In xenograft models, CB-5083 causes modulation of key p97-related pathways, induces apoptosis and has antitumor activity in a broad range of both hematological and solid tumor models. Molecular determinants of CB-5083 activity include expression of genes in the ERAD pathway providing a potential strategy for patient selection.

Introduction

Oncogene-targeted therapies have made important contributions to the treatment of cancer (Ramos and Bentires-Alj, 2014); however resistance to these therapies is common and likely to be a consequence of the plasticity and heterogeneity of cancer cell populations (Meacham and Morrison, 2013). The concept of non-oncogene addiction has recently been used to describe cellular processes that are not intrinsically oncogenic but on which certain cancer cells rely for accelerated and unregulated growth (Luo et al., 2009). These non-oncogene addiction pathways include DNA damage repair, mitosis, metabolism, immune response, epigenetics and protein homeostasis. By targeting these pathways, the aim is to mitigate cancer cell growth even when diverse oncogenic mutations are at play.

Protein homeostasis refers to the balance between protein synthesis, folding, quality control and degradation and encompasses various pathways which many cancer cells are heavily reliant upon for their growth and survival. The high protein synthetic rate and rapid cell cycle of these cancer cells can make them more dependent on the “quality control” provided by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), a central pathway controlling the degradative aspect of protein homeostasis (Van Drie, 2011). The relevance of targeting the UPS has been proven in the clinical setting by the success of the proteasome inhibitors in hematologic malignancies (Wustrow et al., 2013). However, development of resistance (Ruschak et al., 2011) and lack of activity in solid tumor settings (Milano et al., 2009; Wright, 2010) support the need to develop inhibitors of other regulators of protein homeostasis.

p97, also known as Valosin-containing protein, is an essential and conserved member of the AAA family of ATPases. Although the cellular functions associated with p97 are diverse, including organelle membrane homotypic fusion and sorting of endosomal cargo, it is clear that one of its most important functions is as a key regulator of protein homeostasis (Meyer et al., 2012). Through interaction with a number of distinct cofactors, p97 mediates the extraction of proteins destined for destruction by the UPS from organelles, chromatin and protein complexes. For example, interaction with UBX cofactors mediates interactions with various E3 ligases to direct p97 to certain protein degradation processes. p97 is a key regulator of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD), which is the main quality control mechanism for soluble, membrane-associated, glycosylated proteins as well as nonglycosylated proteins as they are processed through the ER (Rabinovich et al., 2002; Ye et al., 2001). The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a pathway that acts both to resolve unfolded protein stress as well as to trigger cell death when the buildup of such unfolded proteins becomes irresolvable (Miura, 2014). Given that many cancer cells can have a high reliance on their UPR and ERAD pathways as a result of their high protein synthetic burden and possibly aneuploidy (Deshaies, 2014; Oromendia and Amon, 2014), and that a block in ERAD following inhibition of p97 function is likely to lead to irresolvable proteotoxic stress, these pathways provide a potential targetable vulnerability in cancer cells.

Recent efforts to discover small molecule inhibitors of p97 have resulted in the identification of several classes of well characterized ATP-competitive and allosteric inhibitors (Chou et al., 2011; Chou et al., 2013; Magnaghi et al., 2013). Although these compounds have served as important tools to understand more fully the cellular consequences of inhibiting p97, they have modest potency, their specificity is not fully characterized and they lack the drug-like properties required for in vivo pre-clinical and clinical development. We set out to discover a potent and specific small molecule inhibitor of p97 with drug-like properties to allow for the clinical evaluation of targeting this important component of protein homeostasis as a therapeutic approach to treat cancer.

Results

CB-5083 is a potent and selective inhibitor of p97

DBeQ and ML240 (Chou et al., 2011; Chou et al., 2013) were used as starting points to initiate extensive lead optimization efforts that led to the identification of the compound CB-5083 with improved p97 inhibition in biochemical and cellular assays along with pharmaceutical properties suitable for clinical development (medicinal chemistry manuscript in preparation). CB-5083 (1-[4-(benzylamino)-5H,7H,8H-pyrano[4,3-d]pyrimidin-2-yl]-2-methyl-1H-indole-4-carboxamide) is a p97 ATPase activity inhibitor with a biochemical IC50 of 11 nM when tested at an ATP concentration of 500 μM (Figures 1A ,1B and S1A). Addition of high concentrations of ATP to the biochemical assay caused an increase in the IC50 of CB-5083, indicating competitive inhibition of at least one of the two ATP binding sites in p97 (Figure 1C). The first p97 AAA-ATPase domain (D1), which has a minor contribution to overall ATPase activity, is situated near the amino terminal domain that interacts with various cofactors. The second AAA-ATPase domain (D2) is the main driver of ATPase activity in biochemical reactions (Song et al., 2003). An ATP hydrolysis deficient mutant of the D1 ATPase site (E305Q) was inhibited by CB-5083 at a similar potency as wild type p97 with an IC50 of 15.4 nM, whereas we were unable to calculate an IC50 for the D2 ATP hydrolysis mutant (E578Q) owing to limitations in solubility above 20 μM, suggesting high selectivity of CB-5083 for the D2 ATPase site of p97 (Figures 1B and S1B) (Dalal et al., 2004). Interestingly, in an ATPase biochemical assay that contains an ATP regeneration system, the maximum inhibition of wild type p97 was only 70.7% whereas in an ATPase assay without an ATP regeneration system maximum inhibition was 95.6%, suggesting that, in the presence of ADP the contribution to ATP hydrolysis of the D1 ATPase site is minimal but in the CB-5083 D2-bound state with low ADP concentrations the ATP hydrolysis of D1 is substantial (Figure S1C). Therefore, CB-5083 is characterized as a D2-selective and potent inhibitor (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. CB-5083 is a potent inhibitor of p97’s D2 ATPase domain.

(A) Chemical Structure of CB-5083

(B) Dose-response curve of CB-5083 with recombinant WT p97, p97E305Q and p97E578Q mutant proteins in an NADH coupled ATPase assay. The assay was conducted at 60 nM enzyme, 500 μM ATP and shown concentrations of CB-5083. R2 values were 0.98, 0.99 and 0.97 for WT, E305Q and E578Q respectively.

(C) ATP competition assay of CB-5083 with WT p97 with increasing ATP concentration.

(D) Crystal structure of p97-D2 showing ADP binding site and relative position of mutations found in resistant cells.

(E) Comparison of IC50 values of shown compounds for p97 in biochemical assay utilizing NADH-based ATPase assay and cell viability assays utilizing ADP-glo.

Error bars are +/− SEM. See also Figure S1 and Tables S1 and S2.

In order to determine the selectivity of CB-5083 for the D2 domain of p97 over other ATP utilizing enzymes, a probe binding/mass spectrometry approach was utilized (Patricelli et al., 2011). When tumor cell lysates were incubated with the biotinylated ATP probe and 10 μM CB-5083, mass spectrometry was used to identify which peptides were no longer bound by the probe in the presence of CB-5083. The D2 ATPase site of p97 was not bound by the probe in the presence of CB-5083 whereas the D1 ATPase site of p97 was still efficiently bound, further confirming the D2 selectivity and ATP competitive binding of CB-5083 (Figure S1D). Among the 164 ATPase sites and 194 kinase sites bound by the probe in the tumor cell lysate, only DNA-PK, mTOR and PIK3C3 were identified to have significant reduction of binding with 10 μM CB-5083 treatment (Figure S1D, Table S1). Consistent with this finding, when CB-5083 was tested in a panel of kinase biochemical assays at a dose of 5 μM, DNA-PK, mTOR and PIK3C3 were the top hits. Subsequent dose titration assays revealed that CB-5083 had 29.6, 128 and 158 fold less affinity for DNA-PK, mTOR and PIK3C3, respectively, compared to p97 (Figures S1D, S1E and Table S2). Furthermore, in a cell-based assay, CB-5083 was shown not to inhibit DNA-PK at concentrations that caused cell death (Figure S1F). Together these data suggest that CB-5083 is a highly selective inhibitor for the D2 site of p97.

Generating drug adapted cell lines that harbor resistance followed by target gene sequencing is a method that can be used to determine compound specificity (Wacker et al., 2012). To identify the cellular target of CB-5083, HCT116 colon cancer cells were treated with increasing concentrations of CB-5083 and mutation-driven drug resistant clones were selected. Resistant clones demonstrated 2-50 fold shifts in the GI50 of CB-5083 in a 72 hr viability assay (Figure S1G). p97 cDNA was isolated from these clones and sequenced. Single homozygous coding mutations that mapped either directly in or adjacent to the D2 ATPase domain were found in the majority of CB-5083 resistant clones (Figures 1D and S1H). Furthermore, when several of the identified mutations were introduced into recombinant p97, changes in biochemical potency of CB-5083 were similar to what was mutant cell viability and recombinant protein sensitivity to CB-5083 suggest that p97 mutations are driving cellular resistance in the analyzed clones further supporting on-target specificity of CB-5083 (Figures S1I and S1J).

Cellular effects of CB-5083

We next wanted to characterize the cellular pharmacodynamic (PD) effects of CB-5083. Given the prominent role of p97 in ERAD, we treated HEK293T cells stably expressing TCRα-GFP, a validated ERAD substrate (DeLaBarre et al., 2006), with CB-5083. CB-5083 treatment led to a dose-dependent accumulation of TCRα-GFP in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with an EC50 of 0.73 μM ± 0.04 μM, suggesting a direct block in ER extraction (Figures 2A and 2B). On the contrary, inhibition of proteasome activity with bortezomib led to an accumulation of TCRα-GFP in the cytoplasm and aggresomes, suggesting that blocking protein degradation is not sufficient to trap TCRα-GFP in the ER. To determine if CB-5083 blocks ERAD-independent protein degradation, we evaluated the stability of the cytoplasmic UPS substrate GFPu (Bence et al., 2001). The accumulation of GFPu was observed after CB-5083 treatment with similar potency to what was seen with TCRα-GFP (EC50: 1.05 μM ± 0.01 μM) (Figures S2A and S2B). To monitor the impact on endogenous substrate degradation, we measured accumulation of endogenous K48 poly-ubiquitinated proteins visualized by immunofluorescence in the lung carcinoma cell line A549. Accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins following CB-5083 treatment was seen initially in the cytoplasm but then primarily in the nucleus at later time points, supporting the notion that ERAD-independent substrate degradation is also blocked (Figures 2C, 2D and S2C). The predominant nuclear accumulation of K48 poly-ubiquitin with CB-5083 was in contrast to bortezomib treatment that caused poly-ubiquitinated protein accumulation primarily in the cytoplasm and aggresomes (Figures 2C, 2D, and S2D). Consistent with a p97 role in nuclear protein extraction(Meerang et al., 2011), A549 cells transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting p97 that led to a reduction in p97 protein levels, showed a similar nuclear accumulation of K48 poly-ubiquitin compared to CB-5083 treatment (Figures S2E, S2F). Additionally, K48-ubiquitinated proteins from CB-5083 treated HCT116 cells accumulated at a higher molecular weight when compared to bortezomib treated cells (Figure 2E). These data suggest that p97 inhibition has a direct role in nuclear and cytosolic protein degradation in addition to its effect on ERAD.

Figure 2. CB-5083 blocks major cellular protein degradation functions.

(A) Example images of HEK293 cells expressing TCRα-GFP with RFP labeled endoplasmic reticulum (ER-RFP) treated with 2.5 μM CB-5083 or 1 μM bortezomib for 6 hr. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(B) Analysis of TCRα-GFP fluorescence in cells treated with dose titration of CB-5083 or bortezomib. R2 values were 0.95 and 0.93 for bortezomib and CB-5083 respectively.

(C) Example images of NSCLC lung cancer cell line A549 labeled with anti-K48 ubiquitin (K48-Ub) and anti-p62 antibodies treated with 2.5 μM CB-5083 or 1 μM bortezomib for 6 hr. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(D) K48-Uband p62 were evaluated by immunofluorescence in A549 cells treated with dose titration of CB-5083 or bortezomib. R2 values were 0.91 and 0.94 for bortezomib and CB-5083 respectively.

(E) Colon cancer cell line HCT116 was treated with CB-5083 or bortezomib for 24 hr. K48-Ubiquitin conjugates and p53 were analyzed by western blot.

(F) p62 modulation was evaluated by immunofluorescence in A549 cells treated with CB-5083, bortezomib, NMS-873, INK128 and Bafilomycin A1. R2 values were and 0.96, 0.93, 0.83, 0.78 and 0.86 for CB-5083, NMS-873, bafilomycin A1, INK128 and bortezomib respectively.

Error bars are +/− SEM. See also Figures S2.

p97 has also been shown to play a critical role in autophagy, another major cellular pathway for protein degradation (Bug and Meyer, 2012). To determine if CB-5083 modulated autophagy, we visualized the autophagy adaptor protein p62 (also known as sequestosome 1) (Bjorkoy et al., 2006) by immunofluorescence after drug treatment in A549 cells (Figures 2C, 2Fand S2C). Upon CB-5083 treatment, p62 was targeted to peri-nuclear foci, some of which co-localized with the K48 poly-ubiquitin and Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) puncta. These foci rapidly cleared from cells, a phenotype that is consistent with the activation of autophagy, which is in contradiction to the previously defined role for p97 as a mediator of autophagy. In support of the notion that CB-5083 activates rather than inhibits autophagy, the mTOR inhibitor INK-128, which activates autophagy, (Schenone et al., 2011) also caused a decrease in p62 levels (Figure 2F and S2G). Conversely, the autophagy inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (Yamamoto et al., 1998) caused an accumulation of p62 in peri-nuclear foci that co-localized with the key autophagy regulator LC3. Additionally, bortezomib, which had previously been shown to induce autophagy, and NMS-873, a structurally distinct p97 inhibitor, both caused decreases in p62 levels. siRNA-mediated knockdown of p97 also caused a punctate redistribution and a decrease in the level of p62, suggesting the observed CB-5083 effect on this pathway is through p97 (Figures S2H). To determine if the loss of p62 was mediated through autophagy, CB-5083 was combined with bafilomycin A1, this resulted in a block of the p62 clearance seen with CB-5083 alone (Figure S2I). These data indicate that autophagy is likely activated by CB-5083, which is consistent with studies that report induction of ER stress leads to strong autophagy activation (Ogata et al., 2006).

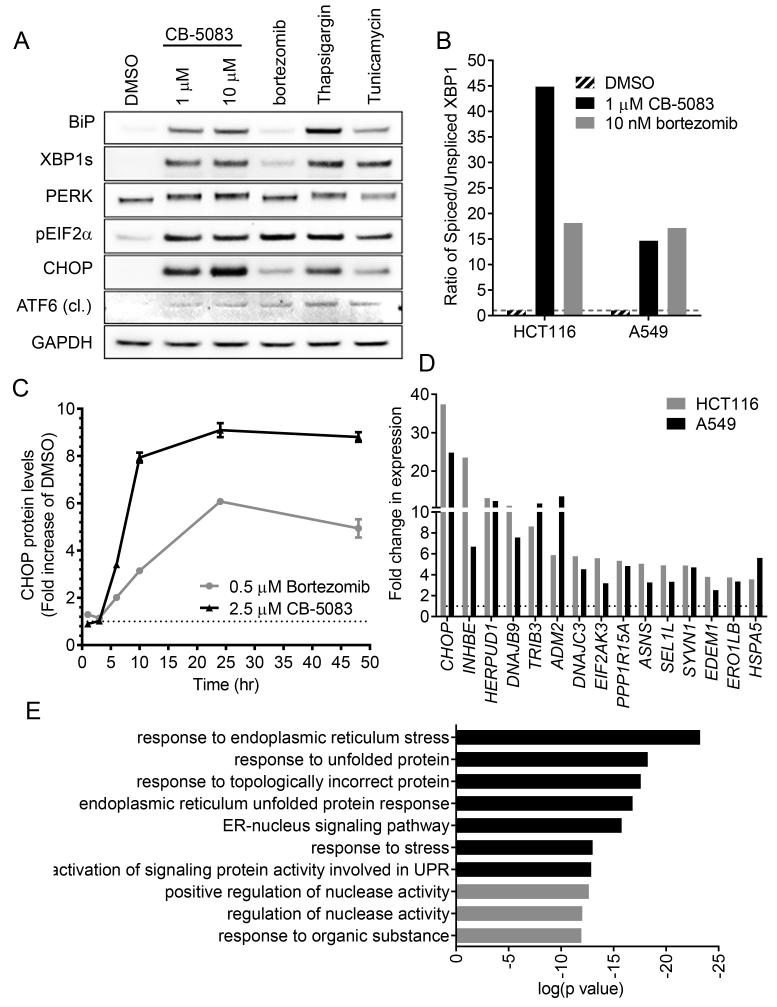

Accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER and other organelles can trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Sano and Reed, 2013). The UPR can be activated via one of three pathways: inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) or protein kinase R (PKR)–like kinase (PERK). CB-5083 caused activation of all three branches of the UPR to levels that were greater in most cases than treatment with bortezomib and comparable to treatment with the sarcoplasmic ER calcium–ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin or the glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin (Figures 3A and 3B). Induction of any branch of the UPR can lead to the accumulation of the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) (Wang et al., 2007; Yoshida et al., 2000). A rapid and sustained induction of CHOP protein was seen with CB-5083 treatment of A549 cells, with an EC50 of 1.19 μM ± 0.23 μM (Figures 3A, 3C, S3A and S3B).

Figure 3. CB-5083 induces a strong unfolded protein response.

(A) A549 cells were treated with CB-5083, bortezomib (1 μM), thapsigargin (1 μM) or tunicamycin (2 μg/ml) for 8 hr. Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies against BiP, spliced XBP1 (XBP1s), PERK, phospho-EIF2a, CHOP, cleaved (cl) ATF6 and GAPDH.

(B) A549 cells were treated with CB-5083 (2.5 μM) or bortezomib (0.5 μM) for the indicated times and CHOP protein levels were quantified by immunofluorescence staining.

(C) A549 or HCT116 cells were treated with CB-5083 (1 μM) for 8 hr. Relative gene expression of a panel of UPR genes, spliced XBP1 and unspliced XBP1 were measured by RT-PCR.

(D) A549 or HCT116 cells were treated with CB-5083 (1 μM) or bortezomib (10 nM) for 8 hr. Relative gene expression of spliced and unspliced XBP1 were measured by RT-PCR.

(E) HCT116 cells were treated with CB-5083 (1 μM) for 8 hr and processed for RNA-seq. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed on top 500 upregulated genes. Top ten most significant GO terms are listed.

To further investigate UPR activation, the expression levels of genes involved in UPR and ER function were measured by RT-PCR after cells were treated with CB-5083. Many genes were up--regulated upon CB-5083 treatment (Figure 3D, Table S3). CHOP was the most highly up-regulated gene within the RT-PCR panel in both A549 cells and colorectal carcinoma cell line HCT116 when treated with CB-5083. Heat shock 70 kDa protein 5 (BiP), which is an ER resident chaperone involved directly in UPR and other gene less directly involved were also up-regulated suggesting a strong transcriptional response of this pathway (Table S3). Genes encoding several components of the ERAD machinery such as HERPUD1, SEL1L, SYVN1, EDEM1 and HSPA5 were also among the most up-regulated genes suggesting a potential compensatory mechanism specific to the inhibition of ERAD. To determine if CB-5083 mediated induction of gene expression was specific to the UPR, transcriptome expression analysis was conducted using RNAseq. Following gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of up-regulated genes, we found that the most significant GO terms were related to UPR or ER stress (Figure 3E). Together, these data suggest that CB-5083 causes a strong and specific UPR response in cancer cells, which is very consistent with a specific inhibition of its target, p97.

CB-5083 causes cancer cell death

Death receptor 5 (DR5) has recently been shown to play an essential role in UPR-induced cell death (Lu et al., 2014). Consistent with induction of the UPR, CB-5083 induced an 18.9-fold up-regulation of DR5 mRNA and a 7.7-fold up-regulation of DR5 protein in HCT116 cells after 24 hr of treatment (Figures 4A and S4A), increases in DR5 protein were seen at time points where increases in CHOP were observed (Figures S4A and S4B). DR5 has been shown to activate caspase-8 as a means of initiating the apoptosis cascade (Lu et al., 2014). Upon CB-5083 treatment in A549 and HCT116 cells induction of caspase-8 and caspase-3/7 coincided with up regulation of DR5 (Figures 4B and 4C). Viability in both of these cell lines also began to decrease with a timing that is coincident with DR5 induction and caspase activation (Figure 4D). Potencies of cell death were similar to potencies of K48 poly-ubiquitin and CHOP protein accumulation suggesting that the buildup of proteins marked for degradation and induction of the UPR may be linked to cell death (Figures 2D, S3B and S4C).

Figure 4. Induction of UPR by CB-5083 causes cancer cell death.

(A) A549 cells were treated with CB-5083 (1 μM) for the indicated times. Relative DR5 gene expression was measured by RT-PCR.

(B-D) A549 or HCT116 cells were treated with CB-5083 (5 μM) for up to 72 hr. Caspase-8 activity (B), caspase-3/7 activity (C) or cell count (D) were measured at indicated times.

(E) BiP, PERK, CHOP, DR5 and caspase-8 were knocked down in HCT116 cells for 24 hr. Cells were then treated with CB-5083 (2.5 μM) for 24 hr and cell viability was measured by cell titer glo.

Error bars are +/− SEM. See also Figure S4.

To determine if CHOP pathway induction was driving cellular cytotoxicity, HCT116 cells were treated with CB-5083 after siRNA-mediated knockdown of BiP, PERK, CHOP, DR5 or Caspase-8 (Figure 4E). Knockdown of BiP, which is a chaperone protein that acts in protective mechanisms of the UPR (Morris et al., 1997), did not block the decrease in viability seen with CB-5083 treatment. siRNA-mediated knockdown of CHOP, but not PERK, blocked CB-5083 mediated cell death suggesting that not all UPR pathways mediate CB-5083-induced cell death. Knockdown of DR5 or caspase-8, which act downstream of CHOP to mediate apoptosis, also caused a block in CB-5083-induced cell death. Similar effects were seen in A549 cells when DR5 or caspase-8 were knocked down (Figure S4D). Further, when cells were treated with siRNA oligos targeting DR5, DR5 protein induction upon CB-5083 treatment was strongly reduced (Figure S4A). When CB-5083 was combined with the CDK inhibitor Dinaciclib, which inhibits the induction of CHOP (Nguyen and Grant, 2014), antagonism of cellular cytotoxicity was observed (Figures S4E). Together these data strongly support the conclusion that CHOP-mediated apoptosis is an important mechanism of CB-5083 induced cellular cytotoxicity.

CB-5083 induces the UPR and apoptosis in xenograft tumor models

To evaluate its pharmacokinetic (PK) and PD activity, CB-5083 was administered at escalating dose levels to female nude mice bearing HCT116 xenograft tumors. Following a single oral dose of CB-5083, there was a dose-dependent increase in area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (Figure 5A). Accumulation of poly-ubiquitin and CHOP in tumor tissue was observed in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 5B and 5C). Increases in DR5 protein were also seen (Figure S5A). Additionally, p62 protein levels decreased by 60% at 6 hr at the 100 mg/kg dose level, consistent with what was observed in vitro (Figure 5D). To determine if markers of apoptosis were activated in CB-5083 treated xenograft models, the levels of cleaved poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) were monitored. Increases in cleaved PARP were observed in a dose-dependent manner with timing that was consistent with the induction of CHOP (Figures 5E). These data demonstrate that CB-5083 achieved plasma concentrations that were sufficient to elicit a PD as well as an apoptotic response in tumors.

Figure 5. CB-5083 has activity in mouse models.

(A) Tumor (open box) and plasma (open circle) concentrations of CB-5083 in tumor tissue extracts from nude mice bearing HCT116 tumors after treatment at 25 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg.

(B-E) Levels of poly-ubiquitin (B), CHOP (C), p62 (D), and cleaved PARP (E) were measured in tumor tissue extracts from nude mice bearing HCT116 tumors after treatment at 25 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg of CB-5083.

(F) Tumor growth was measured for various CB-5083 dosing schedules in the HCT116 xenograft model (n=7-10).

(G) Tumor growth was measured with dosing of CB-5083 in NCI-H1838 (n=16), AMO-1 (n=12), CTG-0360 (n=4), CTG-0081 (n=4) xenograft models.

Error bars are +/− SEM. See also Figure S5.

CB-5083 has antitumor activity in xenograft tumor models

Given the strong UPR and apoptotic response seen with CB-5083 treatment in animal models, the antitumor activity of CB-5083 was assessed in nude or SCID-Beige mice bearing established human tumor xenografts derived from tumor cell lines of different histologic origins: HCT116 derived from colorectal adenocarcinoma, NCI-H1838 derived from non-small cell lung cancer, AMO-1 derived from a plasmacytoma, as well as two colorectal cancer patient derived xenograft (PDX) models (Figures 5F-5G). CB-5083 was administered by oral gavage (po), once (qd) or twice (bid) daily, or following a four days on, three days off (qd4/3off) cycle. Inhibition of tumor growth (% TGI) was calculated on the last day of treatment. All CB-5083 dosing schedules tested were tolerated in tumor-bearing mice, generally resulting in weight loss of <10% (Figure S5B-S5D). The qd4/3off schedule offered the best therapeutic index, with significant (78%, p<0.0001) tumor growth inhibition (TGI) of HCT116 tumor observed at 100 mg/kg (Figure 5F). In contrast, a 25 mg/kg bid dose induced 54% TGI (p<0.0001) and a 50 mg/kg qd dose resulted in 62% TGI (p<0.0001). These results were consistent with the PK and PD results where 100 mg/kg clearly induced the highest level of apoptosis after a single administration (Figures 5A-E) and support the notion of dose-dependent antitumor activity. To confirm that the antitumor effects with CB-5083 in the HCT116 xenograft model were due to inhibition of p97, the resistant HCT116 cell line model harboring the T688A p97 mutation, which causes strong biochemical and cellular resistance to CB-5083, was tested. Tumor growth of this mutant model was not inhibited when dosed with CB-5083 at 90 mg/kg (Figure S5E). A strong antitumor activity was seen with the qd4/3off schedule in NCI-H1838 xenografts and the colorectal carcinoma PDX models. AMO-1 was the most sensitive cell line identified among 350 cell lines that were tested in vitro (IC50= 81 nM; see below) and gave the most striking result in xenograft growth inhibition, with complete regressions of tumors observed in 6/12 animals, after 2 cycles of treatment (Figure 5G). The activity seen in the AMO1 xenograft, a model derived from multiple myeloma, is consistent with the high sensitivity seen in this indication for other protein homeostasis pathway inhibitors such as bortezomib (Hideshima et al., 2001). These results demonstrate that oral treatment with CB-5083 inhibits the growth of human tumor xenografts in mice.

CB-5083 is more effective in solid tumor models than proteasome inhibitors

To understand further the antitumor effect of CB-5083 and the advantage of targeting protein homeostasis via inhibition of p97, comparative studies with proteasome inhibitors were conducted in solid tumor xenograft models. Proteasome inhibitors are approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma (bortezomib and carfilzomib) and mantle cell lymphoma (bortezomib) but have failed to show sustainable activity in solid tumors (Milano et al., 2009; Wright, 2010). We compared the PD activity of CB-5083, bortezomib, carfilzomib and ixazomib in female nude mice bearing HCT116 or A549 tumors. All agents were dosed at their optimal dosing route and published active dose in hematological models (Kupperman et al., 2010; Teicher et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2013) and were generally well tolerated after repeat dosing (Figures S6). After a single administration of CB-5083, a strong and sustained induction of polyubiquitin was observed in tumor tissue suggesting inhibition of the protein homeostasis pathway (Figures 6A). Additionally, a clear CHOP protein accumulation 6 hours post dosing was seen with CB-5083 (Figure 6B), suggesting UPR activation in these tumors. In contrast to CB-5083, none of the proteasome inhibitors were able to show significant, sustained accumulation of poly-ubiquitin or CHOP. The clear difference seen in the PD experiment was confirmed by evaluating tumor growth inhibition. CB-5083 showed a significant antitumor response in HCT 116 xenografts (Figure 6C, TGI = 63%, p<0.0001), whereas none of the proteasome inhibitors were active in this model. In A549 (Figure 6C), CB-5083 was the most potent agent, with 85% TGI (p<0.001). In this model, carfilzomib (TGI = 50%, p<0.0001), and bortezomib (TGI = 37%, p<0.0001) showed modest activity, whereas ixazomib was inactive (TGI =19%, p= 0.0285). Together these data demonstrate that targeting p97 may be a more effective strategy for inhibiting solid tumor growth than targeting the proteasome.

Figure 6. CB-5083 demonstrates greater activity than proteasome inhibitors in solid tumor models.

(A) Relative levels of poly-ubiquitin measured in HCT116 or A549 xenografts in mice administered CB-5083 or proteasome inhibitors (n=3 per time point).

(B) Relative levels of CHOP measured in HCT116 xenografts in (A).

(C) Tumor growth was measured with dosing of CB-5083 or proteasome inhibitors in HCT116 (n=8-12) and A549 (n=10-12) xenograft models.

Error bars are +/− SEM. See also Figure S6.

Determinants of CB-5083 sensitivity

Given the variability in potency seen both in cell culture and in animals, we wanted to determine the molecular determinants of CB-5083 sensitivity or resistance. Potency of cell death induction was measured in 350 cancer cell lines representing a variety of tumor histologies (Figure 7A). The range in sensitivity to CB-5083 was narrow in this cell line panel, with EC50s ranging from 81 nM to 2.1 μM, possibly owing to the pleiotropic cellular functions of p97. A good correlation was seen between EC50 and TGI for cell lines in which antitumor activity had been measured in vivo (R2 = 0.51), suggesting that molecular determinants that drive sensitivity to CB-5083 may translate from cell culture to xenograft models (Figure 7B). Genomic data for the cell line panel were obtained from the cancer cell line encyclopedia (CCLE)(Barretina et al., 2012) and analyzed to determine which molecular and gene expression alterations correlated with CB-5083 sensitivity. Using linear regression, gene expression and copy number information from CCLE was compared to CB-5083 sensitivity. 93 genes by mRNA expression and 94 gene loci by copy number were identified to correlate significantly with either CB-5083 sensitivity or resistance as determined by the false discovery method (Benjamini and Yekutieli, 2001). To further validate the significance of gene correlates with CB-5083 sensitivity, drug sensitivity was randomized prior to linear regression resulting in a strong decrease in the significance of the gene correlates, which further supports that the un-randomized gene correlates are biologically significant (Figure S7A).

Figure 7. Activation of MAPK pathway correlates with sensitivity to CB-5083 in cancer cells.

(A) 340 cancer cell lines were treated with a dose titration of CB-5083, EC50 of cell viability was measured at 72 hr. Cell lines are ordered by EC50.

(B) Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) of a panel of cell lines in subcutaneous xenografts after oral administration of 100 mg/kg CB-5083 on a qd 4 days on 3 days off schedule for 3-4 weeks was compared to EC50 of the same cell lines grown in culture in a 72 hr viability assay.

(C) p97 gene copy number as measured by hybrid capture was plotted against CB-5083 EC50 of viability in a panel of cancer cell lines. Statistical significance of fit to linear regression is calculated with an F test (p value).

(D) p97 mRNA level as measured by microarray was plotted against CB-5083 EC50 of viability in a panel of cancer cell lines. Statistical significance of fit to linear regression is calculated with an F test (p value).

(E) Viability in A549 cells stably expressing inducible control shRNA or shRNA targeting p97 after 3 days of 500 μM IPTG treatment to induce the expression of shRNAs followed by 3 days of CB-5083 treatment. EC50 values were compared to p97 protein levels as measured by Western blot.

(F) CB-5083 EC50 of viability in cell lines containing an oncogenic mutation in KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, BRAF, or NF1 were compared to cells that were wild-type for all of these genes.

(G) CB-5083 EC50 of viability in cell lines with high or low levels of phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2 were compared.

(H) TGI for a set of cell lines grown as xenografts was plotted against the ratio of phosphorylated ERK1+ ERK2 to total ERK1+ ERK2 as measured by Western blot.

See also Figure S7.

Both gene copy number and mRNA level of p97 correlated with resistance to CB-5083 treatment with statistical significance, however given the low Pearson correlation (r) values, it is clear that other determinants of sensitivity exist across the diverse cell panel (Figures 7C and 7D). To determine if p97 levels specify sensitivity to CB-5083, we cloned individual p97-targeted sgRNAs within the CRISPRi and CRISPRa platform in K562 leukemia cells (Gilbert et al., 2014) and quantified their effect on p97 expression by qPCR. Changes in the p97 mRNA level were moderate, likely due to the high basal expression of this abundant protein. We then determined the effect of p97 mRNA expression levels on CB-5083 sensitivity in a competitive growth assay and found an excellent correlation, with a Pearson correlation R2 of 0.97 (Figures S7B-D). Additionally, when p97 was knocked down in HCT116 cells using a stable inducible shRNA system resulting in a strong reduction in protein, CB-5083 EC50 shifted on average from 0.48 μM in the uninduced cells to 0.09 μM in the induced cells (Figures 7E and S7E-H). Together, the connection between p97 mRNA and protein expression and drug sensitivity further supports the notion of on-target antitumor activity of CB-5083.

High gene expression of DR5 was among the top correlates with CB-5083 sensitivity (Figure S7I), which is consistent with the UPR-cell death pathway being critical for CB-5083-mediated cell death. High expression of two genes involved in ERAD were also identified as correlating with CB-5083 sensitivity; autocrine motility factor receptor (AMFR/gp78) which is an E3 that directly associates with p97 (Song et al., 2005) and enhancing α-mannosidase–like protein (EDEM1) which recognizes misfolded proteins and is tethered to p97 through the Derlins (Oda et al., 2006) (Figures S7I). Together these data suggest that cells with elevated ERAD and UPR activity may be more susceptible to p97 inhibition.

When gene mutations were compared to CB-5083 sensitivity, KRAS and BRAF were among the top correlating mutant genes. Given the role of the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway in stimulating protein synthesis (Dasgupta et al., 2005), activating mutations in this pathway may cause an increased dependency on the UPS. When cell lines with any mutation in genes associated with driving MAPK activation were compared to wild type cells, there was also a correlation between activating mutations and sensitivity to CB-5083 (Figure 7F). To look at downstream activation of the MAPK pathway, phosphorylation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) was monitored. Samples with high levels of phospho-ERK1/2 were more sensitive to CB-5083, both in cell culture and xenograft models (Figures 7G, 7H and S7L). Together, these data suggest that cancer cells with activation of the MAPK pathway may rely heavily on p97’s function in protein homeostasis and thus be more sensitive to an inhibitor of p97 such as CB-5083.

Discussion

There is growing evidence that p97 is an important regulator of proteotoxic stress and protein homeostasis; thus inhibition of p97 function provides an opportunity to target a key vulnerability of cancer (Deshaies, 2014 ). We have described the activity of a p97 small molecule inhibitor with drug-like properties. CB-5083 is a potent p97 inhibitor that exhibits strong selectivity against other ATPases and kinases. Although no detectable inhibition of other ATPases and only minor inhibition of several kinases was observed, it remains possible that CB-5083 could target additional ATPases which may have not been captured by our mass spectrometry approach or biochemical screening. However, there is clear evidence that if this were the case, it does not contribute strongly to cellular cytotoxicity seen with CB-5083. When resistant mutant cell lines were generated against CB-5083, amino acid mutations within the D2 ATPase region of p97 were identified and recapitulated in recombinant protein, leading to 50-fold shifts in cell EC50. Together, these data give us confidence that the vast majority of cellular phenotypes and cytotoxicity induced by CB-5083 are driven through p97 inhibition.

Inhibition of p97 through CB-5083 was shown to have a profound effect on the UPR, activating all three arms of this conserved stress response pathway. It is intriguing that the extent of UPR activation induced by CB-5083 was markedly higher than that induced by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Consistent with a recent study that characterized the sequential degradative pathway for a specific ERAD substrate (Morris et al., 2014), bortezomib treatment appeared to allow for the exit of TCRα from the ER, which may be the cause of lower UPR induction compared to p97 inhibition where protein substrates are trapped in the ER following CB-5083 treatment. Alternatively, the differential induction of the UPR by CB-5083 and bortezomib may be due to the different subset of proteins whose degradation is block by these key regulators of protein homeostasis.

Our data suggest that the primary mechanism of cell death for CB-5083 appeared to be mediated through irresolvable proteotoxic stress. CHOP and DR5 induction caused by CB-5083 treatment were required for early induction of caspase activity and cellular cytotoxicity. At later time points cells do eventually die with CHOP or DR5 depletion (data not shown), suggesting that there are other mechanisms of cellular cytotoxicity when p97 is inhibited or that knockdown is not complete. This is not surprising given the numerous cellular functions assigned to p97. Consistent with this notion Eeyarestatin I, a p97 interacting molecule that also binds directly to ER membranes, induces cell death through ATF3, ATF4 and Noxa (Wang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). These alternate routes of cell death observed may be due to the different mode of binding between CB-5083 and Eeyarestatin I or due to different cellular systems used in these studies.

Interestingly, it appeared as though not all cellular functions of p97 were inhibited by CB-5083. For example, we did not see disruption of Golgi or ER morphology at active concentrations of CB-5083 (data not shown), suggesting that the membrane homotypic fusion function of p97 may not be blocked. Additionally, p97 has been widely reported to be required for the process of autophagy (Ju et al., 2009; Meyer et al., 2012). The marked clearance of p62 suggests autophagy is not inhibited with CB-5083 treatment. Possibilities that could explain the lack of activity of CB-5083 on certain p97 functions are its specificity for the D2 ATPase domain of p97 or that it binds preferentially to a specific p97-containing cofactor complex. Recent work reported differential activity of p97 inhibitors on D1 and D2 sites as well as shifts in potency in the presence of the p47 cofactor (Fang et al., 2015). It will be interesting to interrogate the specific cofactor interactions of CB-5083-bound p97 and how these might relate to certain cellular functions. The role of autophagy as a compensatory mechanism to evade the effects of a p97 inhibitor remains unclear although other approved anti-cancer agents appear to induce autophagy to a similar extent.

Several small molecule inhibitors of p97 have been described in the literature (Chou et al., 2011; Chou et al., 2013; Magnaghi et al., 2013 ), however none has demonstrated in vivo activity. CB-5083 has demonstrated drug-like pharmaceutical properties and modulates UPS, UPR and autophagy pathway markers in animal models with magnitudes and timings which are similar to what was seen in cell culture experiments, suggesting inhibition of p97 leads to the same phenotypes in vivo as it does in vitro. CB-5083 also has strong antitumor activity in hematological and solid tumor models. CB-5083 was less active in HCT116 tumors harboring a resistant p97 point mutation suggesting that the efficacy seen in other models is a result of on-target activity. The activity seen in solid tumor models treated with CB-5083 may have profound implications for targeting protein homeostasis beyond hematological disorders, which has been difficult to achieve in the clinic with proteasome inhibitors (Johnson, 2015). Higher UPR induction seen with p97 inhibition in vivo combined with oral administration allowing sustained exposure of drug in the plasma, may also contribute to greater solid tumor activity when compared to proteasome inhibitors and may provide an opportunity to identify patients more likely to respond to CB-5083 (see below).

Given the potential role of p97 in normal cells it will be important to establish the molecular determinants of tumor cell sensitivity to CB-5083 in order to better identify patients that might have a clinical response at dose levels which are also well tolerated. By screening a large panel of cancer cell lines we were able to identify statistically significant genomic features that correlate with either CB-5083 sensitivity or resistance. The identification of high p97 copy number and expression levels as genomic features that correlate with resistance to CB-5083 is intriguing. These data further validated p97 as the cellular target of CB-5083 and suggest that elevated levels of p97 may be a viable exclusion criterion in the clinic. However, p97 expression level has been reported to correlate with poor prognosis (Fessart et al., 2013), suggesting that high expression of p97 may drive cancer progression. p97 appears to fall in the category of drug targets where expression of a target correlates with resistance to a given inhibitor such as the classical example of DHFR amplification in methotrexate resistant cells (Cillo et al., 1987) rather than correlating with sensitivity such as was recently reported for the mitochondrial protein degradation enzyme, ClpP (Cole et al., 2015).

The correlation of high expression of UPR and ERAD-related genes with sensitivity to CB-5083 further supports the role of the UPR as the primary driver of cellular cytotoxicity. We hypothesize that cancer cells with a high basal burden on their ERAD and UPR pathways are more likely to allow CB-5083 to tip the balance toward irresolvable proteotoxic stress and that elevated basal levels of genes such as DR5 may be indicators of greater susceptibility to proteotoxic stress-induced death. The correlation of MAPK pathway activation and CB-5083 sensitivity was less expected although it also makes sense that pathways activating protein synthesis would rely more heavily on protein degradation to maintain protein homeostasis. One downstream effect of having an activated MAPK pathway is increased protein synthesis (Dasgupta et al., 2005). Another mechanism that can drive increased protein synthesis is the activation of eIF4E by ERK (Flynn et al., 1997). Given this hypothesis, CB-5083 may be active in a diverse collection of MAPK activation settings whereas specific targeted agents such as vemurafenib (Bucheit and Davies, 2014) are only active in settings where the specific target is mutated. Furthermore, CB-5083 may be active as a second line therapy in those patients who become resistant to such targeted agents or even in combination to increase durability of responses.

Given the above, CB-5083 was progressed through preclinical development and is currently being evaluated in two phase 1 clinical trials, in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma and in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Experimental Procedures

Biochemical assays

WT and mutant p97 proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3) E.coli cells utilizing the pD441-NH vector with a T5 inducible promoter (DNA2.0), as a His-tagged protein and purified by FPLC His-Trap column chromatography. The hexameric p97 complex was further separated by FPLC S200 size-exclusion chromatography. CB-5083 IC50 analyses for p97 and mutants were conducted utilizing a standard NADH-based coupled kinetic ATPase assay and the ADP glo assay (Promega). See supplemental materials for assay details.

Cell Assays

TCRα and GFPu cell lines were a kind gift from Ron Kopito (Stanford). Cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured according to supplier’s instructions. Immunofluorescence and Western blotting assay were conducted using standard procedures. For qPCR assays, RNA was extracted from cell lystaes and cDNA was prepared. Transcript levels were measured by qPCR using a UPR PCR array (SABiosciences) or Taqman primers in the QuantStudio 6 Flex PCR system (Life Technologies). See supplemental materials for further assay details.

Animal studies

The animal research conducted for this paper was reviewed and approved by the Cleave Biosciences’ Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were treated in accordance to guidelines outlined by the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (ILAR) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female athymic nude mice and SCID Beige mice, 5-8 weeks of age and weighing approximately 20-25 grams were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Details about animal husbandry can be found in the supplemental materials. Cancer cell line xenografts were established by implanting 5 × 106 - 10 × 106 cells subcutaneously. CB-5083, MLN9708 and the CB-5083 vehicle (0.5% methyl cellulose in water) were administered by oral gavage, bortezomib and carfilzomib by tail vein injection. Tumor volume and body weights were measured twice weekly and daily, respectively, throughout the study.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 related to Figure 1. CB-5083 has little ATP-binding pocket competition in panel of kinases and ATPases.

The percent displacement of the Desthiobiotin-ATP probe was measured by mass-spec for a panel of kinases and ATPases from HeLa cell lysates treated with 10 μM CB-5083.

Table S2 related to Figure 1. CB-5083 has minimal kinase inhibitor activity.

The percent activity in a panel of kinase assay after treatment with 10 μM CB-5083.

Figure S1. Selectivity of CB-5083. Related to Figure 1.

(A+B) Change in O.D at 340 nm measured over time in NADH biochemical assay reporting on the ATPase activity of WT p97 (A) or p87 E305Q (B) with a dose titration of CB-5083.

(C) Dose titration of CB-5083 in the ADP-glo ATPase assay for WT p97 and p97 E305Q. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98 and 1.00 for WT and E305Q respectively.

(D) Table summarizing off target activity of CB-5083 on select AAA-ATPases and kinases.

(E) Dose titration of CB-5083 in DNAPK, mTOR and PIK3C3 kinase assays compared to p97. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 1.00, 1.00, 1.00 and 0.99 for DNAPK, mTOR, PIK3C3 and p97 WT respectively.

(F) Cellular activity of DNA-PK was measured by monitoring levels of nuclear phospho-H2AX by immunofluorescence in A549 cells treated with NU7441, CB-5083 or bortezomib for 6 hr.

(G) Dose titration of CB-5083 in 72 hr viability assay in cell lines with induced resistance to CB-5083 and identified point mutations in p97. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98, 0.97, 0.84, 0.91, 0.90, 0.86 and 0.92 for parental, WT clone, P472L, Q473P, V474A, N660K and T688A respectively.

(H) Table summarizing the fold-change in viability EC50 for cell lines with identified p97 point mutations.

(I) Table summarizing the fold-change in biochemical IC50 for given p97 mutations.

(J) Scatterplot comparing fold-change in EC50 of CB-5083 in cell lines with given mutation to fold change in IC50 of CB-5083 for ATPase activity in recombinant p97 with given mutations.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S2. CB-5083 and p97 siRNA modulate pathway markers. Related to Figure 2.

(A) Example images of HEK293 cells expressing GFPu treated with CB-5083 or bortezomib for 8 hr. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(B) Analysis of GFPu fluorescence in cells treated with dose titration of CB-5083 or bortezomib. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.88 and 0.93 for bortezomib and CB-5083 respectively.

(C and D) Example images of A549 cells stained by immunofluorescence for p62 and K48-ub after a time-course of CB-5083 (5 μM, C) or bortezomib (100 nM, D) treatment. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(E) Analysis of p97 protein levels by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 48 hr after transfection with siRNA oligos targeting p97. Scale bar is 50 μm and applies to all panels.

(F) Analysis of K48-ub levels by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 48 hr after transfection with siRNA oligos targeting p97 or 6 hr after CB-5083 (2.5 μM) or bortezomib (240 nM) treatment. Scale bar is 50 μm and applies to all panels.

(G) Analysis of p62 protein levels by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 48hr after transfection with siRNA oligos targeting p97 or 6 hr after CB-5083 (2.5 μM) or bortezomib (240 nM) treatment. Scale bar is 50 μm and applies to all panels.

(H) Example images of A549 cells stained by immunofluorescence for p62 and LC3 after treatment with CB-5083, Bafilomycin A1 or INK-128. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(I) Quantification p62 as measured by immunofluorescence in A549 cells after treatment with 10 μM CB-5083 +/− 100 nM Bafilomycin A1.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S3. CB-5083 causes accumulation of CHOP protein. Related to Figure 3.

(A) Example images of NSCLC lung cancer cell line A549 labeled with anti-CHOP antibodies treated with CB-5083, bortezomib or Thapsigargin for 6 hr. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(B) Analysis of nuclear levels of CHOP protein measured by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 6 hr after a dose titration of CB-5083, bortezomib or thapsigargin. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.97 and 0.88 for CB-5083 and bortezomib respectively. Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S4. CB-5083 causes a strong accumulation of CHOP protein which is blocked by the CDK inhibitor Dinaciclib. Related to Figure 4.

(A) DR5 protein levels were measured by immunofluorescence and cellular intensities were quantified for a dose titration of CB-5083 with or without knockdown of DR5 by siRNA. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.79 and 0.59 for control and siDR5 respectively.

(B) Western blot analysis of DR5 and CHOP in HCT116 cells treated with 1 μM CB-5083.

(C) Nuclear counts were measured by microscope in A549 and HCT116 cell lines following a 72 hr treatment of CB-5083 in dose titration. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.97 and 0.87 for A549 and HCT116 respectively.

(D) DR5 and Caspase 8 were knocked down in A549 cells for 24 hr. Cells were then treated with CB-5083 (5 μM) for 48 hr and cell viability was measured by cell titer glo.

(E) Viability (left) and CHOP protein level (right) were measured in A549 cells following a 72 hr treatment of CB-5083 in dose titration in combination with constant doses of Dinaciclib. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98, 0.24 and 0.96 in DMSO, 0.006 μM and 0.5 μM CB-5083 respectively for CHOP levels and 1.00, 0.9991 and 0.78 for DMSO, 0.006 μM and 0.5 μM CB-5083 respectively for cell viability.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S5 In vivo effects of CB-5083. Related to Figure 5.

(A) Western blot analysis of DR5 in HCT116 xenograft treated with 100 mg/kg CB-5083.

(B-D) Change in body weights were measured daily in HCT116 (B), NCI-H1838 (C) and AMO1 implanted xenograft for efficacy studies described in Figures 5D-F and 6D-E

(E) Tumor growth was measured for CB-5083 dosing in HCT116 xenograft model harboring the p97 T688A mutation. Female nude mice with established HCT 116 T688A xenografts were treated for 25 days (n=10-12). CB-5083, 90 mg/kg PO, qd4/3off (4 days treatment, 3 days holidays per cycle), TGI = 20 %, p = 0.0521.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S6 In vivo effects of CB-5083 and proteasome inhibitors. Related to Figure 6.Change in body weights were measured daily in HCT116 (left) and A549 (right) implanted xenograft for efficacy studies described in Figures 6D-E.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S7. Cell line sensitivity to CB-5083 correlates with gene expression of p97 or select UPR genes. Related to Figure 7.

(A) Top gene expression correlates are plotted in order of significance for cell line EC50 of viability (red) as well as 20 iterations of randomized EC50 data (grey).

(B) Relative resistance to CB-5083 (ρ) was plotted against p97 expression across a set of K562 cell lines expressing CRISPRi and CRISPRa sgRNAs.

(C-D) CRISPRi or CRISPRa lines of human K562 leukemia cells expressing different sgRNAs targeting p97 or a negative control sgRNA were treated with different concentrations of CB-5083 and numbers of live cells were determined by cell titer glo after 72 hr of treatment. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98, 0.97, 0.97, 0.99 and 0.99 for Neg. ctrl, p97_i1, p97_i2, p97_i3 and p97_i4 respectively in (B) and 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.98 and 0.99 in Neg. ctrl, p97_a1, p97_a2, p97_a3 and p97_a4 respectively in (C).

(E-H) Viability in A549 cells stably expressing inducible control shRNA (clone 1 is (E), clone 2 in (F)) or inducible shRNA targeting p97 (clone 1 in (G),m clone 2 in (H)) was measured by cell titer glo after 3 days of 500 μM IPTG treatment followed by 3 days of CB-5083 treatment. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.92, 0.70 for control and +IPTG respectively in (E), 0.93, 0.75 for control and +IPTG respectively in (F), 0.98, 0.89 for control and +IPTG respectively in (G) and 0.91, 0.87 for control and +IPTG respectively in (H).

(I-K) DR5, EDEM1 and AMFR gene expression as measured by microarray was plotted against CB-5083 EC50 of viability in a panel of cancer cell lines.

(L) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 across a panel of xenograft models along with their corresponding % TGI.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Table S3 related to Figure 3. CB-5083 induces the expression of UPR-related genes

Fold change in gene expression of HCT116 and A549 treated with 1 μM CB-5083 for 8 hr compared to DMSO treated cells. Genes were ordered by fold change.

Table S4

Oligos used in siRNA study

Significance.

Protein homeostasis pathways have become attractive targets for treatment of certain tumor types owing to the high protein synthetic rate of these tumors and their consequent heightened dependence on degradative pathways for their growth and survival. p97 is a key mediator of several protein homeostasis processes and is therefore a strong potential cancer target. We identified a small molecule compound, CB-5083, that blocks p97 activity through ATP-competitive binding and has physicochemical properties that enable oral administration. CB-5083 exhibited antitumor activity in tumor models where proteasome inhibitors were inactive. We characterized molecular determinants of sensitivity so that clinical development can be focused on tumor subsets more likely to show a response.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alessandra Cesano, Michael Longi, Raymond Deshaies, Ethan Emberley and Francesco Parlati for scientific discussion and contributions to work presented in this manuscript. We thank L. Gilbert and B. Adamson for discussions regarding the CRISPR studies. M.K. was supported by NIH/NCI Pathway to Independence Award K99 CA181494. B.T.A. is supported by the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation and The Stephen & Nancy Grand Multiple Myeloma Translational Initiative.

Footnotes

Accession number

RNAseq data are uploaded to the gene expression omnibus (GEO) at the NCBI, accession number GSE73588.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J.A., R.L.M, S.D., B.K., F.M.Y., L.S., H.J.Z., D.W., M.R.; Methodology, D.J.A., R.L.M., S.D. B.K., J.R., S.W., J.W., M.K., B.T.A.; Investigation, D.J.A., R.L.M, S.D., B.K., J.R., S.W., J.W., B.Y., E.V., S.K.V.S., A.M., F.S., M.K.M., Z.Y.W., M.K., Y.C.; Resources, B.Y., H.J.Z, D.W.; Writing –Original Draft, D.J.A., R.L.M., S.D., B.K., M.R.; Writing –Review & Editing, D.J.A, R.L.M., S.D, L.S., H.J.Z., D.W., M.R.; Supervision, D.J.A, R.L.M., J.S.W., F.M.Y., L.S., H.J.Z., D.W., M.R.

References

- Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehar J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science. 2001;292:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5521.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. 2001:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1: a missing link between protein aggregates and the autophagy machinery. Autophagy. 2006;2:138–139. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucheit AD, Davies MA. Emerging insights into resistance to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma. Biochemical pharmacology. 2014;87:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bug M, Meyer H. Expanding into new markets – VCP/p97 in endocytosis and autophagy. Journal of Structural Biology. 2012;179:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T-F, Brown SJ, Minond D, Nordin BE, Li K, Jones AC, Chase P, Porubsky PR, Stoltz BM, Schoenen FJ, et al. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitin-dependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:4834–4839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T-F, Li K, Frankowski KJ, Schoenen FJ, Deshaies RJ. Structure–Activity Relationship Study Reveals ML240 and ML241 as Potent and Selective Inhibitors of p97 ATPase. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:297–312. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillo C, Dick JE, Ling V, Hill RP. Generation of drug-resistant variants in metastatic B16 mouse melanoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2604–2608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A, Wang Z, Coyaud E, Voisin V, Gronda M, Jitkova Y, Mattson R, Hurren R, Babovic S, Maclean N, et al. Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Protease ClpP as a Therapeutic Strategy for Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:864–876. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal S, Rosser MF, Cyr DM, Hanson PI. Distinct roles for the AAA ATPases NSF and p97 in the secretory pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:637–648. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta B, Yi Y, Chen DY, Weber JD, Gutmann DH. Proteomic Analysis Reveals Hyperactivation of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Pathway in Neurofibromatosis 1–Associated Human and Mouse Brain Tumors. Cancer Research. 2005;65:2755–2760. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLaBarre B, Christianson JC, Kopito RR, Brunger AT. Central pore residues mediate the p97/VCP activity required for ERAD. Mol Cell. 2006;22:451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies RJ. Proteotoxic crisis, the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and cancer therapy. BMC biology. 2014;12:94. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CJ, Gui L, Zhang X, Moen DR, Li K, Frankowski KJ, Lin HJ, Schoenen FJ, Chou TF. Evaluating p97 Inhibitor Analogues for Their Domain Selectivity and Potency against the p97-p47 Complex. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:52–56. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessart D, Marza E, Taouji S, Delom F, Chevet E. P97/CDC-48: proteostasis control in tumor cell biology. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn A, Vries RG, Proud CG. Signalling pathways which regulate eIF4E. Biochemical Society transactions. 1997;25:192S. doi: 10.1042/bst025192s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, Whitehead EH, Guimaraes C, Panning B, Ploegh HL, Bassik MC, et al. Genome-Scale CRISPR-Mediated Control of Gene Repression and Activation. Cell. 2014;159:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hideshima T, Richardson P, Chauhan D, Palombella VJ, Elliott PJ, Adams J, Anderson KC. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits growth, induces apoptosis, and overcomes drug resistance in human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3071–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE. The ubiquitin-proteasome system: opportunities for therapeutic intervention in solid tumors. Endocrine-related cancer. 2015;22:T1–T17. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju JS, Fuentealba RA, Miller SE, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, Baloh RH, Weihl CC. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;187:875–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupperman E, Lee EC, Cao Y, Bannerman B, Fitzgerald M, Berger A, Yu J, Yang Y, Hales P, Bruzzese F, et al. Evaluation of the proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in preclinical models of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1970–1980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Lawrence DA, Marsters S, Acosta-Alvear D, Kimmig P, Mendez AS, Paton AW, Paton JC, Walter P, Ashkenazi A. Cell death. Opposing unfolded-protein-response signals converge on death receptor 5 to control apoptosis. Science. 2014;345:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1254312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and nononcogene addiction. Cell. 2009;136:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi P, D'Alessio R, Valsasina B, Avanzi N, Rizzi S, Asa D, Gasparri F, Cozzi L, Cucchi U, Orrenius C, et al. Covalent and allosteric inhibitors of the ATPase VCP/p97 induce cancer cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:548–556. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. 2013;501:328–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerang M, Ritz D, Paliwal S, Garajova Z, Bosshard M, Mailand N, Janscak P, Hubscher U, Meyer H, Ramadan K. The ubiquitin-selective segregase VCP/p97 orchestrates the response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/ncb2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H, Bug M, Bremer S. Emerging functions of the VCP/p97 AAA-ATPase in the ubiquitin system. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:117–123. doi: 10.1038/ncb2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano A, Perri F, Caponigro F. The ubiquitin-proteasome system as a molecular target in solid tumors: an update on bortezomib. OncoTargets and therapy. 2009;2:171–178. doi: 10.2147/ott.s4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura G. ER stress: To live or let die. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:695–695. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JA, Dorner AJ, Edwards CA, Hendershot LM, Kaufman RJ. Immunoglobulin binding protein (BiP) function is required to protect cells from endoplasmic reticulum stress but is not required for the secretion of selective proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:4327–4334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris LL, Hartman IZ, Jun DJ, Seemann J, DeBose-Boyd RA. Sequential actions of the AAA-ATPase valosin-containing protein (VCP)/p97 and the proteasome 19 S regulatory particle in sterol-accelerated, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarylcoenzyme A reductase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:19053–19066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.576652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TK, Grant S. Dinaciclib (SCH727965) inhibits the unfolded protein response through a CDK1- and 5-dependent mechanism. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:662–674. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Okada T, Yoshida H, Kaufman RJ, Nagata K, Mori K. Derlin-2 and Derlin-3 are regulated by the mammalian unfolded protein response and are required for ER-associated degradation. The Journal of cell biology. 2006;172:383–393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K, Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K, et al. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oromendia AB, Amon A. Aneuploidy: implications for protein homeostasis and disease. Disease models & mechanisms. 2014;7:15–20. doi: 10.1242/dmm.013391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patricelli MP, Nomanbhoy TK, Wu J, Brown H, Zhou D, Zhang J, Jagannathan S, Aban A, Okerberg E, Herring C, et al. In situ kinase profiling reveals functionally relevant properties of native kinases. Chem Biol. 2011;18:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich E, Kerem A, Frohlich KU, Diamant N, Bar-Nun S. AAA-ATPase p97/Cdc48p, a cytosolic chaperone required for endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:626–634. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.626-634.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos P, Bentires-Alj M. Mechanism-based cancer therapy: resistance to therapy, therapy for resistance. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruschak AM, Slassi M, Kay LE, Schimmer AD. Novel proteasome inhibitors to overcome bortezomib resistance. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103:1007–1017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano R, Reed JC. ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1833:3460–3470. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenone S, Brullo C, Musumeci F, Radi M, Botta M. ATP-competitive inhibitors of mTOR: an update. Current medicinal chemistry. 2011;18:2995–3014. doi: 10.2174/092986711796391651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song BL, Sever N, DeBose-Boyd RA. Gp78, a membrane-anchored ubiquitin ligase, associates with Insig-1 and couples sterol-regulated ubiquitination to degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Mol Cell. 2005;19:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Wang Q, Li CC. ATPase activity of p97-valosin-containing protein (VCP). D2 mediates the major enzyme activity, and D1 contributes to the heat-induced activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:3648–3655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher BA, Ara G, Herbst R, Palombella VJ, Adams J. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in cancer therapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1999;5:2638–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Drie JH. Protein folding, protein homeostasis, and cancer. Chinese journal of cancer. 2011;30:124–137. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker SA, Houghtaling BR, Elemento O, Kapoor TM. Using transcriptome sequencing to identify mechanisms of drug action and resistance. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:235–237. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Mora-Jensen H, Weniger MA, Perez-Galan P, Wolford C, Hai T, Ron D, Chen W, Trenkle W, Wiestner A, Ye Y. ERAD inhibitors integrate ER stress with an epigenetic mechanism to activate BH3-only protein NOXA in cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:2200–2205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807611106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Shinkre BA, Lee JG, Weniger MA, Liu Y, Chen W, Wiestner A, Trenkle WC, Ye Y. The ERAD inhibitor Eeyarestatin I is a bifunctional compound with a membrane-binding domain and a p97/VCP inhibitory group. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Serradell N, Bolos J, Rosa E. YM-155: apoptosis inducer survivin expression inhibitor oncolytic. Drugs Future. 2007;32:879–882. [Google Scholar]

- Wright JJ. Combination Therapy of Bortezomib with Novel Targeted Agents: An Emerging Treatment Strategy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:4094–4104. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wustrow D, Zhou H-J, Rolfe M. Chapter Fourteen - Inhibition of Ubiquitin Proteasome System Enzymes for Anticancer Therapy. In: Manoj CD, editor. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press; 2013. pp. 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Tagawa Y, Yoshimori T, Moriyama Y, Masaki R, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cells. Cell structure and function. 1998;23:33–42. doi: 10.1247/csf.23.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature. 2001;414:652–656. doi: 10.1038/414652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Okada T, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Negishi M, Mori K. ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:6755–6767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6755-6767.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Pham LV, Newberry KJ, Ou Z, Liang R, Qian J, Sun L, Blonska M, You Y, Yang J, et al. In vitro and in vivo therapeutic efficacy of carfilzomib in mantle cell lymphoma: targeting the immunoproteasome. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2494–2504. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 related to Figure 1. CB-5083 has little ATP-binding pocket competition in panel of kinases and ATPases.

The percent displacement of the Desthiobiotin-ATP probe was measured by mass-spec for a panel of kinases and ATPases from HeLa cell lysates treated with 10 μM CB-5083.

Table S2 related to Figure 1. CB-5083 has minimal kinase inhibitor activity.

The percent activity in a panel of kinase assay after treatment with 10 μM CB-5083.

Figure S1. Selectivity of CB-5083. Related to Figure 1.

(A+B) Change in O.D at 340 nm measured over time in NADH biochemical assay reporting on the ATPase activity of WT p97 (A) or p87 E305Q (B) with a dose titration of CB-5083.

(C) Dose titration of CB-5083 in the ADP-glo ATPase assay for WT p97 and p97 E305Q. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98 and 1.00 for WT and E305Q respectively.

(D) Table summarizing off target activity of CB-5083 on select AAA-ATPases and kinases.

(E) Dose titration of CB-5083 in DNAPK, mTOR and PIK3C3 kinase assays compared to p97. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 1.00, 1.00, 1.00 and 0.99 for DNAPK, mTOR, PIK3C3 and p97 WT respectively.

(F) Cellular activity of DNA-PK was measured by monitoring levels of nuclear phospho-H2AX by immunofluorescence in A549 cells treated with NU7441, CB-5083 or bortezomib for 6 hr.

(G) Dose titration of CB-5083 in 72 hr viability assay in cell lines with induced resistance to CB-5083 and identified point mutations in p97. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98, 0.97, 0.84, 0.91, 0.90, 0.86 and 0.92 for parental, WT clone, P472L, Q473P, V474A, N660K and T688A respectively.

(H) Table summarizing the fold-change in viability EC50 for cell lines with identified p97 point mutations.

(I) Table summarizing the fold-change in biochemical IC50 for given p97 mutations.

(J) Scatterplot comparing fold-change in EC50 of CB-5083 in cell lines with given mutation to fold change in IC50 of CB-5083 for ATPase activity in recombinant p97 with given mutations.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S2. CB-5083 and p97 siRNA modulate pathway markers. Related to Figure 2.

(A) Example images of HEK293 cells expressing GFPu treated with CB-5083 or bortezomib for 8 hr. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(B) Analysis of GFPu fluorescence in cells treated with dose titration of CB-5083 or bortezomib. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.88 and 0.93 for bortezomib and CB-5083 respectively.

(C and D) Example images of A549 cells stained by immunofluorescence for p62 and K48-ub after a time-course of CB-5083 (5 μM, C) or bortezomib (100 nM, D) treatment. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(E) Analysis of p97 protein levels by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 48 hr after transfection with siRNA oligos targeting p97. Scale bar is 50 μm and applies to all panels.

(F) Analysis of K48-ub levels by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 48 hr after transfection with siRNA oligos targeting p97 or 6 hr after CB-5083 (2.5 μM) or bortezomib (240 nM) treatment. Scale bar is 50 μm and applies to all panels.

(G) Analysis of p62 protein levels by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 48hr after transfection with siRNA oligos targeting p97 or 6 hr after CB-5083 (2.5 μM) or bortezomib (240 nM) treatment. Scale bar is 50 μm and applies to all panels.

(H) Example images of A549 cells stained by immunofluorescence for p62 and LC3 after treatment with CB-5083, Bafilomycin A1 or INK-128. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(I) Quantification p62 as measured by immunofluorescence in A549 cells after treatment with 10 μM CB-5083 +/− 100 nM Bafilomycin A1.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S3. CB-5083 causes accumulation of CHOP protein. Related to Figure 3.

(A) Example images of NSCLC lung cancer cell line A549 labeled with anti-CHOP antibodies treated with CB-5083, bortezomib or Thapsigargin for 6 hr. Scale bar is 20 μm and applies to all panels.

(B) Analysis of nuclear levels of CHOP protein measured by immunofluorescence in A549 cells 6 hr after a dose titration of CB-5083, bortezomib or thapsigargin. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.97 and 0.88 for CB-5083 and bortezomib respectively. Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S4. CB-5083 causes a strong accumulation of CHOP protein which is blocked by the CDK inhibitor Dinaciclib. Related to Figure 4.

(A) DR5 protein levels were measured by immunofluorescence and cellular intensities were quantified for a dose titration of CB-5083 with or without knockdown of DR5 by siRNA. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.79 and 0.59 for control and siDR5 respectively.

(B) Western blot analysis of DR5 and CHOP in HCT116 cells treated with 1 μM CB-5083.

(C) Nuclear counts were measured by microscope in A549 and HCT116 cell lines following a 72 hr treatment of CB-5083 in dose titration. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.97 and 0.87 for A549 and HCT116 respectively.

(D) DR5 and Caspase 8 were knocked down in A549 cells for 24 hr. Cells were then treated with CB-5083 (5 μM) for 48 hr and cell viability was measured by cell titer glo.

(E) Viability (left) and CHOP protein level (right) were measured in A549 cells following a 72 hr treatment of CB-5083 in dose titration in combination with constant doses of Dinaciclib. Dose responses were fit to a 4-parameter sigmoid curve with R2 values of 0.98, 0.24 and 0.96 in DMSO, 0.006 μM and 0.5 μM CB-5083 respectively for CHOP levels and 1.00, 0.9991 and 0.78 for DMSO, 0.006 μM and 0.5 μM CB-5083 respectively for cell viability.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S5 In vivo effects of CB-5083. Related to Figure 5.

(A) Western blot analysis of DR5 in HCT116 xenograft treated with 100 mg/kg CB-5083.

(B-D) Change in body weights were measured daily in HCT116 (B), NCI-H1838 (C) and AMO1 implanted xenograft for efficacy studies described in Figures 5D-F and 6D-E

(E) Tumor growth was measured for CB-5083 dosing in HCT116 xenograft model harboring the p97 T688A mutation. Female nude mice with established HCT 116 T688A xenografts were treated for 25 days (n=10-12). CB-5083, 90 mg/kg PO, qd4/3off (4 days treatment, 3 days holidays per cycle), TGI = 20 %, p = 0.0521.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S6 In vivo effects of CB-5083 and proteasome inhibitors. Related to Figure 6.Change in body weights were measured daily in HCT116 (left) and A549 (right) implanted xenograft for efficacy studies described in Figures 6D-E.

Error bars are +/− SEM.

Figure S7. Cell line sensitivity to CB-5083 correlates with gene expression of p97 or select UPR genes. Related to Figure 7.

(A) Top gene expression correlates are plotted in order of significance for cell line EC50 of viability (red) as well as 20 iterations of randomized EC50 data (grey).