Abstract

Please cite this paper as: Van Buynder et al. (2010) Marketing paediatric influenza vaccination: results of a major metropolitan trial. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 5(1), 33–38.

Objectives After a cluster of rapidly fulminant influenza related toddler deaths in a Western Australian metropolis, children aged six to 59 months were offered influenza vaccination in subsequent winters. Some parental resistance was expected and previous poor uptake of paediatric influenza vaccination overseas was noted. A marketing campaign addressing barriers to immunization was developed to maximise uptake.

Design Advertising occurred in major statewide newspapers, via public poster displays and static ‘eye‐lite’ displays, via press releases, via a series of rolling radio advertisements, via direct marketing to child care centres, and via a linked series of web‐sites. Parents were subsequently surveyed to assess reasons for vaccination.

Main Outcome Results The campaign produced influenza vaccination coverage above that previously described elsewhere and led to a proportionate reduction in influenza notifications in this age group compared to previous seasons.

Conclusions Influenza in children comes with significant morbidity and some mortality. Paediatric influenza vaccination is safe, well tolerated and effective if two doses are given. A targeted media campaign can increase vaccine uptake if it reinforces the seriousness of influenza and addresses community ‘myths’ about influenza and influenza vaccine. The lessons learned enabling enhancements of similar programs elsewhere.

Keywords: Coverage, influenza, marketing, paediatric, vaccination

Introduction

In the winter of 2007, a cluster of rapidly fulminant influenza‐related deaths occurred in a six‐day period in three toddlers aged 2 years in Perth, Western Australian (WA), a city of just over 1 million people. The deaths were unusual in that progression to death occurred in all within 24 hours of onset of relatively vague symptoms, gross pathological findings were absent on post‐mortem, and influenza A was detected in tissues without attributable secondary bacterial co‐infections.

After media reports of the cluster, (http://www.news.com.au/child‐deaths‐blamed‐on‐flu/story‐e6frfkp9‐1111113904546?from=mostpop) parents flooded primary care surgeries and emergency departments for many weeks, the situation compounded by reports of a similar fulminant illness and death two weeks later in a child with pneumococcal disease.

Unlike some countries, Australia neither funded childhood influenza vaccination at this time, nor had a policy of specifically recommending it in children without coexisting risk factors.

The health care–associated impact of the cluster led to a review of external data and of potential mitigation strategies by the WA Department of Health Communicable Disease Control Directorate.

It was apparent early in the review that influenza in children was under‐recognized, and its importance underestimated. Available data suggested that influenza caused significant morbidity and hospitalizations and also some mortality particularly in children under 5 years of age. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Children were also likely to shed virus for longer periods and to be an important contributor to continued propagation of influenza in the community. 6

Additionally, influenza vaccination in children had been shown to be safe and to be effective if two doses were initially given to immunologically prime young children. 7 , 8 Data also existed to support some indirect benefit to older groups if children were vaccinated. 9

The scientific debate in Australia about the benefit of vaccinating children against the virus had been clouded by the global lack of relevant effectiveness data particularly in children <24 months, 10 and doubts about the capacity of the health care system to cope with the additional doctors visits required to implement the programme.

A decision was made to implement a formal trial of influenza vaccine effectiveness in the Perth metropolitan area in children aged six to 59 months during the 2008 Southern winter; a cohort of around 80 000 children. Two vaccine manufacturers, Sanofi Pasteur and CSL, agreed to provide the influenza Trivalent Inactivated Vaccine (TIV) for free, and the WA Department of Health funded the costs of the prospective case–control study and the associated marketing campaign.

In view of the poor uptake of paediatric influenza vaccine, despite supportive recommendations in the United States (US), 11 , 12 a decision was made to combine the vaccination programme with a public marketing campaign. This paper describes the campaign and its outcomes.

Methodology

Prior to the commencement of the campaign, a series of public focus groups were conducted by a marketing group specializing in this activity, to assess the attitude of parents of target group children to influenza vaccination and to identify any barriers that would need addressing. Each of the groups typically involved around ten parents from across societal strata.

As a result of the focus group discussions, the three key campaign messages were given as follows:

-

1

Influenza in children is a serious disease (with references to the previous year’s cluster of deaths);

-

2

Influenza vaccine is effective in children; and,

-

3

Influenza vaccine is safe, has minimal side effects, and cannot give you influenza.

The campaign was initially focused on print media advertising in major statewide newspapers (for example Figure 1), press releases, public poster displays (1, 2) and static ‘eye‐lite’ displays in baby changing rooms and thoroughfares near pharmacies in shopping centres. The press releases by the Department of Health were weekly to the community journals and adventitiously to metropolitan dailies, using coverage updates to generate media interest. A series of rolling radio advertisements were placed in those radio stations reaching the greatest proportion of target age mothers. These radio spots included tag lines attached to hourly news updates (2, 3). Direct marketing occurred three times to child care centres and included posters and individual letters to be sent home to parents. Letters also went to primary care physicians and to workplaces. The former included specific information about the low risk of egg allergy and the availability of immunology clinics for this group. A linked series of websites (http://www.flukills.org.au and http://www.public.health.wa.gov.au) were set up and a viral advertisement (http://303.com.au/projects/snotfunny/index.htm) was distributed via progressive emails.

Figure 1.

Newspaper and poster advertisement.

Figure 2.

A poster linking the message to the radio.

Figure 3.

A newspaper tag line.

The paid media campaign was triphasic with an initial launch in April, a follow‐up campaign highlighting the need for second doses in late May and a campaign focused on respiratory hygiene messages with a secondary vaccination message in June.

Free vaccine was available through primary care physicians and a large public service clinic in the metropolitan area.

The campaign was assessed via a number of related activities. A Computer‐Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) survey was conducted. The sample was obtained from a database of children whose parents had agreed to be recalled for subsequent studies, who were within the age range and who had answered questions about their health and well‐being within the previous 9 months (October 2007 to June 2008) on the continuous WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System (HWSS). All children within the age range were selected, and 94% of the parents surveyed agreed to be recalled for other studies.

The response rate for the HWSS for those months was 82.5% on randomly selected monthly samples (range 80.5–85.2% over the 9 months – none went below 80%) and the response rate for the children who could be contacted was 96.5% with 2.2% refusal and 1.3% for respondent unavailable during survey time). This gives an overall response rate of about 75% taking into account the per cent agreeing to be recalled, the initial response rate and the response rate attained in the recall study. As a randomly selected sample originally, they were representative of the population. The demographic characteristics of those recalled did not differ significantly by age, gender or geographical area (the weighting variables). All the results presented were weighted to compensate for oversampling in rural and remote WA areas and then adjusted to the age and sex distribution of the population. Complex samples in SPSS 15.1 were used to calculate estimates and confidence intervals.

Additionally, interviews were conducted with parents of symptomatic children recruited to the WA Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness study (WAIVE) at the tertiary paediatric hospital and within sentinel general practices.

Physicians were required to fax in updates of vaccination numbers to access replacement doses. The WAIVE interviews were not combined with the CATI data.

Finally, the medical impact of the campaign was assessed by comparing the influenza notification rate in the target age group that year to the year before when vaccine was not given.

Results

The vaccine coverage rate was assessed in two ways. The CATI survey identified 183 parents who had at least one child under the age of 5 years. Standardizing the results of this survey against the known metropolitan area population gave a vaccination rate of 52% for children having the first dose of vaccine and 47% having received a second dose. The symptomatic children recruited to the WAIVE study (n = 361) had a first dose vaccination rate of 52% and a second dose coverage of 36%. Thus, it is likely that just over half the target group received influenza vaccine and of these just over 80% received a second dose. Over 150 children with ‘anaphylaxis to egg protein’ as determined by the referring practitioner were successfully vaccinated with no adverse events (unpublished data).

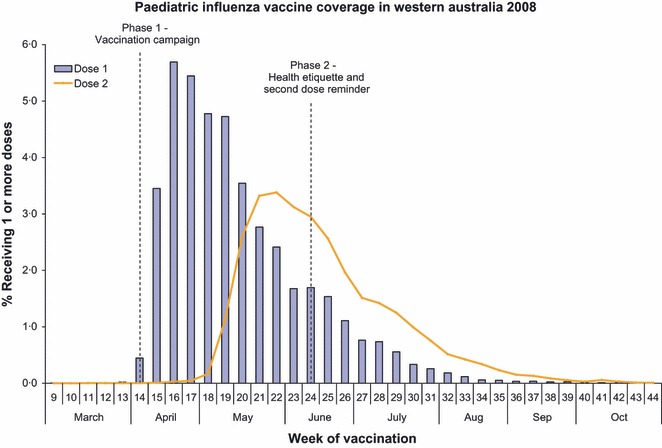

The relationship between the timing of the media campaign and the vaccination uptake is shown in Figure 4. The peak uptake of initial vaccination occurred in the week of the campaign commencement. There was no evidence of a significant boost from the second phase of the campaign promoting second doses of vaccine. Anecdotally, most children were booked for the second dose by the attending physician at the time of the first dose.

Figure 4.

Paediatric Influenza Vaccine Coverage in Western Australia 2008.

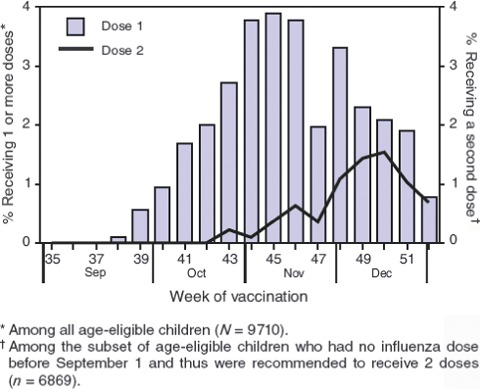

The comparative paediatric influenza vaccine uptake rates and timings of vaccination in a recent US northern winter is shown in Figure 5. The coverage in the US is about half of that achieved in WA and the uptake more gradual.

Figure 5.

Vaccination Coverage over time in US 2006 (MMWR 2008;57:1039–43).

The medical impact of vaccinating the children was significant with the influenza notification rate in the target age group in Western Australia almost halving from the previous year despite comparable influenza seasons. (rate ratio 2008/2007 = 0.54, 95% CI 0.43–0.68, P < 0.001). (http://www.public.health.wa.gov.au/cproot/2172/2/DW13no1Mar2009vFinalweb.pdf)

The CATI survey also examined parental views on campaign messages and reasons for vaccination decisions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parental responses to CATI survey

| Parental views of major contributions to decisions to vaccinate | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Concern about the impact of influenza on children | 90.9 |

| Knowing vaccine is very safe | 90.9 |

| Worried about childhood deaths the year before | 81.9 |

| Knowing the vaccine cannot give you influenza | 66.7 |

| Recommended by health care professional | 59.1 |

| Recommended by family and friends | 47.0 |

| Information from the media campaign | 45.4 |

| Parental views of major contributions to decisions not to vaccinate | Frequency (%) |

| Concern about vaccine safety | 27.7 |

| Belief that influenza is not a serious illness | 24.7 |

| Belief that vaccine would give my child the flu | 20.9 |

| Worry about how my child would behave | 12.8 |

| Difficulty accessing physician | 12.0 |

| Recommended not to by physician | 10.3 |

Those deciding to vaccinate children had a high proportion of people who found the media messages informative (82.6%) and believable (77%). They were also concerned about the severity of influenza, believed the vaccine to be safe and had a trusted health care provider or family source recommend vaccination (Table 1).

Conversely, those deciding not to vaccinate were a more diverse grouping but generally rejected the key messages of the campaign. Sadly, almost a quarter of these either could not access a physician or having accessed one were dissuaded from vaccination.

The major reasons listed for children not receiving second doses of vaccine were being too busy and/or not being able to get an appointment with their physician (58%).

Accessing trusted sources outside of the media campaign was a prominent activity in parents surveyed. Two‐thirds consulted family and friends, around half consulted a physician and just less than this proportion spoke to other health professionals. Around 30% of parents researched the issue on the internet.

Discussion

Establishing and maintaining high vaccination coverage against vaccine preventable diseases is a constant challenge for public health departments. The immunization schedule is ever‐increasingly complex, and there is a decreased community awareness of the impact of the diseases themselves because of the effectiveness of vaccines. Community concern about side effects is often exacerbated by celebrity support for purported side effect linkages and additionally the effectiveness of some vaccines declines over time with waning immunity.

With TIV, community attitudes are further hampered by its variable effectiveness depending on circulating strains, its relative ineffectiveness in key target groups such as the elderly, urban myths surrounding its disease causing potential, occasional rare but severe side effects, and a view that the disease itself is benign based largely on a community association of all winter viruses as the ‘flu’ and the benign nature of the majority of influenza cases.

While many in the community may be lukewarm about the benefits of influenza vaccination, influenza is a major cause of morbidity and hospitalization in the very young. 13 Although some newer influenza vaccines show promise, TIV remains the only influenza vaccine licensed for children in Australia and two doses of TIV have in some previous studies been shown to be effective against influenza in children. 6 , 7 Additionally, while data are insufficient, a recent review of the economic benefit of paediatric influenza vaccination pointed to ‘an economic interest for society of vaccinating children’. 14

The first phase radio and newspaper campaign continued for a period of about 3 weeks and was timed to overlap with a school holiday break. This initial campaign produced the greatest rate of clinic attendance (Figure 4). However, CATI surveying of parents about the most effective component of the campaign failed to identify a key component; a not uncommon outcome in multiphasic, multisystem campaigns.

A review on influenza vaccination in the US for the 2006–2007 influenza season found 31% of children received one dose and 21% were fully vaccinated. 11 The definition of fully vaccinated children included children receiving two doses in different time periods, a group not included in Western Australian data.

Data from the 2005–2006 US influenza season survey identified 32% of children receiving one dose and 21% being fully vaccinated. 12 Although there was great variability between states, usually no improvement was seen from previous seasons data. A comparison of the timing of vaccination between the US and WA shows a more gradual uptake in the US and a lack of high early activity which followed the media campaign in WA. No comparable campaign exists in the US. The US review recommended opportunistic discussion by health care providers with parents, vaccination only clinics and reminder/recall systems. Our data support the importance of these messages. A stand‐alone vaccination clinic in WA administered over 700 vaccines a week during the peak period, and a total of over 5000 overall helping to overcome access issues.

A review of the Canadian paediatric vaccination campaign again found only 27% of children vaccinated with key reasons for non‐vaccination being that immunization caused illness, or weakened the immune system, or that their child was not at risk. 15 This perception amongst many people in the community that influenza is not associated with significant morbidity, or that their child is not at risk, is at odds with the review of childhood deaths in the severe influenza season of 2003–2004. 3 Half the deaths were in previously healthy children, only one‐third had an underlying condition thought to increase the risk of influenza related complications and almost two‐thirds of the healthy children were under 5 years of age.

Caution must be exercised when generalizing from the WA results. The comparably less effective vaccination programmes in the US and Canada are broader based than the Perth metropolitan campaign. It may be that campaigns across the whole of Australia would face a greater challenge to achieve similar results than one so geographically focused. Additionally, the CATI survey results were self‐report, and the survey was not a random sample of the population but a panel of parents interested in participating in research. These parents may also have been more likely to vaccinate their children. While this is plausible, a similar percentage of WAIVE children were vaccinated and they were selected purely on attendance to care with an ILI. This increases the likelihood that CATI coverage rates are true reflection of the community. It is probable that the relatively high rate of vaccination in the WA campaign owed part of its success to parental memory of the childhood death cluster the previous year. Despite this, the barriers to vaccination were identified in initial focus group work, and in previous studies. These barriers were the focus of the marketing campaign and there was high message recognition amongst those vaccinating their children. The programme has been funded to continue for five years and the ability to maintain coverage in the absence of ‘recent paediatric influenza deaths’ will enhance the assessment of the effectiveness of public campaigns in increasing vaccination rates.

Campaigns to support immunization programmes are increasingly important to maintain coverage and ensure herd immunity. Assessing the attributable benefit of these campaigns against a high background coverage is challenging. In WA in the winter of 2008, we had an opportunity to study a natural experiment off a very low base with promising findings.

Conclusions

Influenza in children comes with significant morbidity and some mortality. Paediatric influenza vaccination is safe, well tolerated and effective if two doses are given. A targeted media campaign can increase vaccine uptake if it reinforces the seriousness of influenza and addresses community ‘myths’ about influenza and influenza vaccine. The use of dedicated clinics can also increase coverage as most Western countries report issues with access to primary care physicians. Continued education of health care providers is required as a proportion of children not vaccinating are dissuaded by their carers and few providers opportunistically recruit to vaccination.

References

- 1. Espositi S, Marchisio P, Principi N. The global state of influenza in children. Paediatr Infec Dis J 2008; 27:S149–S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neuzil KM, Mellen BG, Wright PF et al. The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coffin SE, Zaoutis TE, Rosenquist AB et al. Incidents, complications and risk factors for prolonged stay in children hospitalized with community‐acquired influenza. Pediatrics 2007; 119:740–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR et al. Influenza‐associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003–2004. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2559–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newland JG, Laurich VM, Rosenquist AW et al. Neurologic complications in children hospitalized with influenza: characteristics, incidence, and risk factors. J Pediatr 2007; 150:306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vynnycky E, Pitman R, Siddiqui R et al. Estimating the impact of childhood influenza vaccination programmes in England and Wales. Vaccine 2008; 26:5321–5330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eisenberg KW, Szilagyi PG, Fairbrother G et al. Vaccine effectiveness against laboratory‐confirmed influenza in children 6 to 59 months of age during the 2003–2004 and 2004–2005 influenza seasons. Pediatrics 2008; 122:911–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vesikari T, Fleming DM, Aristequi JF et al. Safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of cold‐adapted influenza vaccine‐trivalent against community‐acquired, culture‐confirmed influenza in young children attending day care. J Pediatr 2006; 118:2298–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Principi N, Esposito S, Marchisio P, Gasparini R, Crovari P. Socioeconomic impact of influenza on healthy children and their families. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22:S207–S210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jefferson T, Smith S, Demicheli V et al. Assessment of the efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines in healthy children: systematic review. Lancet 2005; 365:773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. CDC . Influenza vaccination coverage among children 6–23 months – United States, 2006–07 Influenza season. MMWR 2008; 57:1039–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. CDC . Influenza vaccination coverage among children 6–23 months – United States, 2005–06 Influenza season. MMWR 2008; 56:959–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brotherton J, Wang H, Schaffer A et al. Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination coverage in Australia, 2003 to 2005. Commun Dis Intell 2007; 31(Suppl):S1–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Savidan E, Chevat C, Marsh G. Economic evidence of influenza vaccination in children. Health Policy 2008; 86:142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grant VJ, Le Saux N, Plint AC et al. Factors influencing childhood influenza immunization. CMAJ 2003; 168:39–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]