Abstract

Please cite this paper as: Asner et al. (2012) Respiratory viral infections in institutions from late stage of the first and second waves of pandemic A (H1N1) 2009, Ontario, Canada. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 6(3), e11–e15.

We report the impact of respiratory viruses on various outbreak settings by using surveillance data from the late first and second wave periods of the 2009 pandemic. A total of 278/345(78·5%) outbreaks tested positive for at least one respiratory virus by multiplex PCR. We detected A(H1N1)pdm09 in 20·6% of all reported outbreaks of which 54·9% were reported by camps, schools, and day cares (CSDs) and 29·6% by long‐term care facilities (LCFTs), whereas enterovirus/human rhinovirus (ENT/HRV) accounted for 62% outbreaks of which 83·7% were reported by long‐term care facilities (LCTFs). ENT/HRV was frequently identified in LTCF outbreaks involving elderly residents, whereas in CSDs, A(H1N1)pdm09 was primarily detected.

Keywords: Enterovirus/human rhinovirus (ENT/HRV), long‐term care facilities, pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 (A(H1N1)pdm09)

Background and objectives

Respiratory outbreaks are common in healthcare and community institutions such as long‐term care facilities (LTCFs) and schools. 1 , 2 The most commonly identified viruses have been influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). 1 , 2 Human rhinovirus (HRV) has more recently been identified as a major viral pathogen in LTCF outbreaks. 1 Recent data reported by Public Health Ontario (PHO) indicated that pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 [A(H1N1)pdm09] was a rare cause of LTCF respiratory outbreaks during the first period of wave I (April 20–June 12, 2009) of the 2009 pandemic. 3 We used surveillance data from the late stage of the first wave and the duration of the second wave periods (June 11–November 30, 2009) to ascertain the impact of A(H1N1)pdm09 and other respiratory viruses on different outbreak settings such as LTCFs and schools. For the purpose of this study, we considered the period from April 20 to August 31, 2009, as wave I and the period from September 1 to November 30, 2009, as wave II, although wave II activity continued until January 2010. 4

Methods

We investigated all respiratory outbreaks in LTCFs and camps, schools, day cares (CSDs) tested at PHO laboratories from June 11 through November 30, 2009, in Ontario, Canada. A confirmed respiratory infection outbreak in a LTCF, as defined by Ontario’s Ministry of Health (MOH), requires two cases of acute respiratory illness within 48 hours of which at least one has to be laboratory‐confirmed, or three cases of acute respiratory illness occurring within 48 hours in a geographic area, none of which are laboratory‐confirmed. 5 Up to six samples are routinely tested per outbreak, with additional samples tested by special request. PHO’s respiratory outbreak testing algorithm included a multiplex nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) kit (Luminex xTAG Respiratory Viral panel; Luminex Diagnostics, Toronto, ON, Canada) used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations to test nasopharyngeal swabs for viral pathogens [adenovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1‐4, RSV A/B, enterovirus/human rhinovirus (ENT/HRV), coronavirus OC43/229E/NL63/HKU1, and metapneumovirus]. An alternate multiplex NAAT kit (Seeplex RV; Seegene USA, Rockville, MD, USA) was used in conjunction with the Luminex assay during periods of higher demand. An in‐house assay specific for A(H1N1)pdm09 was also performed. 6

Results

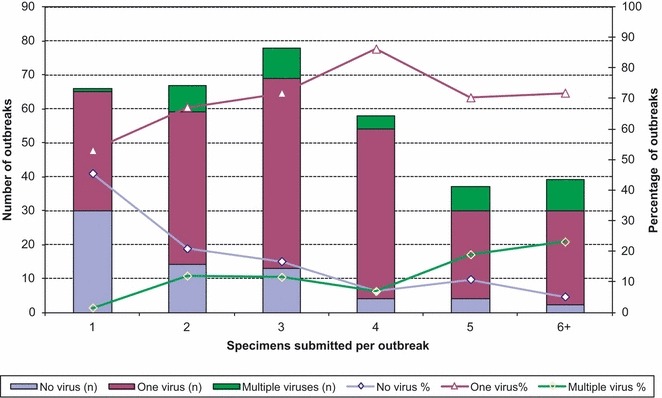

A total of 345 respiratory outbreaks in CSDs, LTCFs, and other facilities (hospitals, correctional facilities, and unknown) were reported to and tested at PHO. Molecular testing was performed on 1117 samples from different outbreak settings. The number of samples submitted per outbreak is shown in Figure 1. Of the average of four samples (range 1–14) tested per outbreak, the median number of positive samples per outbreak was 2 (range 1–8). Outbreak samples mostly originated from LTCFs (76·8%) and CSDs (13·9%). Hospitals and correctional facilities comprised 17(4·9%) and 1 (0·3%) of remaining outbreaks, respectively. Facility type was unknown for 4·1% outbreaks tested. Mean and median ages of all persons tested were 72·1 and 83 years, respectively (range 1–106 years). Mean and median ages of LTCF outbreak cases were 80·9 and 85 years, respectively; CSDs had a much younger population with mean and median ages of 13·4 and 12 years, respectively.

Figure 1.

Relationship between number of samples tested per outbreak and viral positivity.

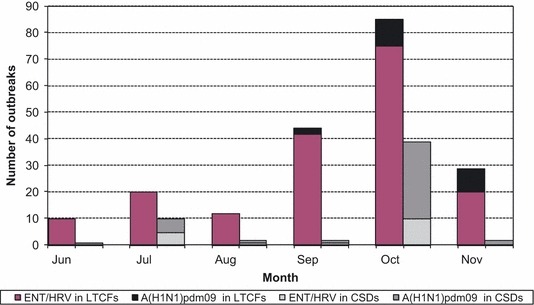

At least one viral agent was identified in 278 (78·5%) of the outbreaks tested. Of these, 84 (30·2%) outbreaks had only one sample with a virus identified, and the remaining 194 (69·8%) had the same virus identified in two or more samples (range 2–8). ENT/HRV and A(H1N1)pdm09 were the most common viruses detected in 214 (62%) and 71 (20·6%) outbreaks, respectively. Of the 71 outbreaks in which A(H1N1)pdm09 was detected, 39 (54·9%) occurred in CSDs, 21 (29·6%) in LTCFs, and 11 (15·5%) in other facilities. Of the 214 outbreaks in which ENT/HRV was identified, 179 (83·7%) occurred in LTCFs, 17 (8%) in CSDs, and 18 (8%) in other facilities (Figure 2). Both viruses were identified throughout the entire study period, reaching a peak during October of wave II (Figure 2). Two hundred and forty outbreaks (69·6%) were caused by a single virus, the most common being ENT/HRV (75%) or A(H1N1)pdm09 (17·9%). One hundred and ninety of these single virus outbreaks occurred in LTCFs and 34 in CSDs. More than one etiological agent was identified in 38 (11%) of the outbreaks, of which 19 (50%) had two or more viruses detected within the same sample (coinfection). The most common coinfection was A(H1N1)pdm09/ENT/HRV, detected in 11 (58%) of the 19 outbreaks with coinfections. In the three outbreaks where two or more samples had viral coinfection (range 2–5 samples with coinfection), the same two viruses were found in all coinfection samples.

Figure 2.

Number of outbreaks with A(H1N1)pdm09 or ERV/HRV identified by month of occurrence and facility type. ENT/HRV, Enterovirus/human rhinovirus; A(H1N1)pdm09, Pandemic 2009 H1N1; LTCFs, Long‐term care facilities; CSDs, Camps, schools, daycares.

There was an increased likelihood of identifying multiple viruses if 5 or more samples were tested (P < 0·05; Figure 1). Nineteen outbreaks with multiple viruses detected were reported in LTCFs and 12 in CSDs. ENT/HRV and A(H1N1)pdm09 were the most common co‐circulating viruses reported in all outbreaks with multiple viruses detected, found in 7 of the 19 multiple virus outbreaks reported by LTCFs and 10 of the 12 multiple virus outbreaks reported by CSDs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Viruses identified among 345 outbreaks occurring in LTCFs, CSDs, and other settings during the 2009 pandemic in Ontario

| LTCFs* | CSDs** | Others*** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single viruses detected n (%) | |||

| ENT/HRV | 163 (61·5) | 6 (12·5) | 11 (34·4) |

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 12 (4·5) | 27 (56·3) | 4 (12·5) |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 6 (2·3) | 1 (2·1) | 0 |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 3 (1·1) | 0 | 0 |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 3 (1·1) | 0 | 1 (3·1) |

| Parainfluenza 4 | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| hMPV | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| RSV B | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple viruses detected n (%) | |||

| ENT/HRV/A(H1N1)pdm09 | 7 (2·6) | 10 (20·8) | 6 (18·8) |

| ENT/HRV/Parainfluenza 1 | 3 (1·1) | 0 | 0 |

| ENT/HRV/Parainfluenza 2 | 1 (0·4) | 0 0 | |

| ENT/HRV/Parainfluenza 4 | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| ENT/HRV/hMPV | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| A(H1N1)pdm09/Parainfluenza 2 | 1 (0·4) | 1 (2·1) | 0 |

| Parainfluenza 2/Parainfluenza 3 | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| Parainfluenza 3/RSV B | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| ENT/HRV/A(H1N1)pdm09/influenza B | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 0 |

| ENT/HRV/A(H1N1)pdm09/Parainfluenza 1 | 0 | 1 (2·1) | 1 (3·1) |

| ENT/HRV/Parainfluenza 1 & 3 | 2 (0·8) | 0 | 0 |

| No viruses detected n (%) | 56 (21·1) | 2 (4·2) | 9 (28·1) |

| Total | 265 | 48 | 32 |

ENT/HRV, Enterovirus/human rhinovirus; A(H1N1)pdm09, Pandemic A(H1N1) 2009; hMPV, Human metapneumovirus; RSV B, Respiratory syncytial virus B.

*LTCFs: Long‐term care facilities.

**CSDs: Camps, schools, day cares.

***Others: Correctional facilities, hospitals, and others than settings mentioned above.

Discussion

Respiratory viruses detected in institutional outbreaks might not necessarily reflect those causing acute respiratory disease in the community especially when involving different age‐groups and exposure risks. Despite an increased number of respiratory outbreaks in LTCFs caused by A(H1N1)pdm09 during the second wave of the 2009 pandemic, A(H1N1)pdm09 continued to constitute a small proportion of detected viruses in this setting. ENT/HRV was detected in the majority of respiratory outbreaks in LTCFs, where the vast majority of residents were elderly. Recently published reports 7 , 8 , 9 have already highlighted these findings. However, this study provides a larger sample size and is unique in that both institutional (predominantly elderly) and community outbreak (predominantly children) settings are described. We also found an increased likelihood of detecting viruses causing outbreaks as the number of specimens tested increased. Viruses causing coinfections may be co‐transmitted between patients as part of the same outbreak, rather than circulating independently of each other.

Additional bacterial analysis would be required to conclude that HRV is the sole etiology of individual outbreaks. In contrast, the pandemic virus was detected in almost all CSD outbreaks, which mostly involved children and younger adults as recently highlighted in the literature. 10 , 11 Possible reasons for a lower prevalence of A(H1N1)pdm09 in LTCFs outbreaks include cross‐protective antibodies from previous exposure to influenza A (H1N1) strains among elderly or minimal exposure to individuals more likely to be infected by the pandemic strain, such as children. 10 , 11

From June 11 to November 30, 2009, we found that ENT/HRV was frequently identified in LTCF outbreaks involving elderly residents, whereas in outbreak settings involving children and younger adults, A(H1N1)pdm09 was primarily detected. Younger children were not well represented in the CSD group, which had a median age of 13·4 years. This likely reflects the age distribution of children that attend sleep away summer camps in Ontario.

Limitations of our study include its observational design, which limits establishment of causality and also limits our ability to exclude the effect of measured or unmeasured confounders in our analysis. A distinction between upper and lower respiratory tract infections, the role of asymptomatic shedding, and comparison of severity of outbreaks could not be performed as clinical data were missing. In Ontario, the local medical officer of health or designate determines whether an institutional outbreak meets the provincial case definition. PHO laboratories do not receive sufficient outbreak information to make this determination. In this context, this study highlights the importance of submitting more than one sample to properly investigate an outbreak. Other bacterial agents like Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Chlamydophila pneumonia could not be ruled out as the cause of outbreaks as samples were not routinely tested for them. A distinction could not be made between staff and resident cases in this study as staff information was not systematically reported. This highlights a current deficiency in the investigation and reporting of staff illness in LTCFs. 9 An increased rate of ENT/HRV outbreaks may have been observed during the pandemic because of increased vigilance by individuals to report symptoms to their healthcare providers, who in turn had a lower threshold to report outbreaks to the public health units who coordinate laboratory investigations. Therefore, we might have seen increased specimen collection and testing that may have influenced our findings.

Identification of specific non‐influenza organisms associated with outbreaks can assist with outbreak management as the period of patient isolation and when to declare an outbreak over are dependent on the incubation period and period of communicability, which varies by organism. Documentation of HRV as a cause of LTCF outbreaks is important, as recent studies suggest that HRV outbreaks can cause severe and fatal disease in LTCFs, especially among the elderly. 1 A study comparing viral outbreaks in different community/facility settings with prospective gathering of detailed clinical and epidemiological information, supported by comprehensive microbiological analysis, will help further understand the role of different respiratory viruses as etiologic agents.

Conflict of interests

Sandra Asner, Adriana Peci, Alex Marchand‐Austin, Anne‐Luise Winter, Romy Olsha, and Erik Kristjanson have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Donald E. Low participated in advisory board committee meetings for GlaxoSmithKline Inc. and Hoffman‐La Roche. He has also received research funding from both companies. Jonathan B. Gubbay has received a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline Inc. to work on resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. In June 2010, OAHPP received a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline to study phenotypic resistance in influenza virus.

References

- 1. Longtin J, Marchand‐Austin A, Winter AL et al. Rhinovirus outbreaks in long‐term care facilities, Ontario, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16:1463–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elliot AJ, Fleming DM. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the elderly. Expert Rev Vaccines 2008; 7:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marchand‐Austin A, Farrell DJ, Jamieson FB et al. Respiratory infection in institutions during early stages of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:2001–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ontario Agency for health protection and promotion (OAHPP) . Laboratory Pandemic Influenza surveillance. Available at http://www.oahpp.ca/resources/documents/reports/labratorysurveillancereports/100329%20OAHPP%20Weekly%20Laboratory%20Surveillance%20Report.pdf (Accessed November 24, 2011).

- 5. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐term care . Appendix B: provincial case definitions for reportable diseases In: Infectious Diseases protocol, 2009, Toronto. Available at http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/pubhealth/oph_standards/ophs/progstds/idprotocol/appendixb/respiratory_outbreaks_cd.pdf (Accessed November 24, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duncan C, Guthrie JL, Tijet N et al. Analytical and clinical validation of novel real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction assays for the clinical detection of swine‐origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 69:167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wald TG, Shult P, Krause P, Miller BA, Drinka P, Gravenstein S. A rhinovirus outbreak among residents of a long‐term care facility. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Atmar RL. Uncommon(ly considered) manifestations of infection with rhinovirus, agent of the common cold. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:266–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Longtin J, Winter AL, Heng D et al. Severe human rhinovirus outbreak associated with fatalities in a long‐term care facility in Ontario, Canada. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:2036–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller E, Hoschler K, Hardelid P, Stanford E, Andrews N, Zambon M. Incidence of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: a cross‐sectional serological study. Lancet 2010; 375:1100–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tuite AR, Greer AL, Whelan M et al. Estimated epidemiologic parameters and morbidity associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza. CMAJ 2010; 182:131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]