Abstract

Please cite this paper as: DeVries et al. (2012) Neuraminidase H275Y and hemagglutinin D222G mutations in a fatal case of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 6(601), e85–e88.

Oseltamivir‐resistant 2009 H1N1 influenza virus infections associated with neuraminidase (NA) H275Y have been identified sporadically. Strains possessing the hemagglutinin (HA) D222G mutation have been detected in small numbers of fatal 2009 H1N1 cases. We report the first clinical description of 2009 H1N1 virus infection with both NA‐H275Y and HA‐D222G mutations detected by pyrosequencing of bronchioalveolar lavage fluid obtained on symptom day 19. The 59‐year‐old immunosuppressed patient had multiple conditions conferring higher risk of prolonged viral replication and severe illness and died on symptom day 34. Further investigations are needed to determine the significance of infection with strains possessing NA‐H275Y and HA‐D222G.

Keywords: 2009 H1N1, fatal, oseltamivir, pandemic influenza, pyrosequencing, resistance, severity

Introduction

A novel influenza A (H1N1) virus was identified in April 2009 that rapidly spread worldwide. The clinical syndrome associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) [2009 H1N1] virus infection has ranged from asymptomatic infection to rapid respiratory decompensation and death. Some host risk factors such as chronic pulmonary disease, pregnancy, immunosuppression, neuromuscular disease, and morbid obesity among others have been associated with more severe outcomes. 1 Viral factors may also influence disease severity. Recently, a mutation in the hemagglutinin gene at position 222 from aspartic acid to glycine (HA‐D222G) in 2009 H1N1 virus was identified in individuals with severe illness or death in Scotland, Norway, and Hong Kong, but not in upper respiratory tract specimens in persons with mild illness, suggesting the possibility of a correlation with more severe clinical outcomes or viral tropism. 2 2009 H1N1 strains possessing D222G have been shown to have enhanced capacity for binding to alpha2‐3 receptors expressed on ciliated cells of the lower respiratory tract (bronchioles, alveoli, type II pneumocytes). 3

Another viral factor that could affect influenza illness outcomes is antiviral resistance. A single mutation at position 275 (N1 numbering) from histidine to tyrosine in the neuraminidase protein (NA‐H275Y) is associated with oseltamivir resistance, but such virus strains are susceptible to zanamivir. The predominant seasonal influenza A (H1N1) virus strains circulating during the 2008–09 Northern Hemisphere influenza season contained the H275Y mutation, but were susceptible to M2 channel blockers. To date, only sporadic reports of oseltamivir resistance have been identified among circulating 2009 H1N1 virus strains, accounting for 1·3% of US isolates.

As part of surveillance for changes in circulating influenza viruses, the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) Public Health Laboratory began limited partial HA and NA gene sequencing of respiratory specimens collected from 2009 H1N1 fatal cases and identified a single patient whose specimen contained mutations for both NA‐H275Y and HA‐D222G.

Materials and methods

All persons hospitalized with influenza‐like illness and all persons with a critical illness or death of a suspected infectious etiology without an alternate cause are reportable to the MDH as required by state law. Investigations of reportable diseases are considered public health response and are classified as exempt by the MDH institutional review board. Medical records were reviewed. Original specimens were tested by real‐time reverse transcription PCR (rRT‐PCR) for 2009 H1N1 viral RNA based on CDC protocol, 4 and pyrosequencing for NA‐H275Y and HA‐222 variants was performed. Viral RNA was extracted via Corbett Life Science’s X‐tractor Gene utilizing Qiagen’s QIAamp Virus BioRobot 9604 Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) per manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT‐PCR) amplifications were performed using SuperScript® III One‐Step RT‐PCR System with Platinum®Taq High Fidelity (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to amplify partial gene regions of both the NA and HA genes. NA amplicons were generated, and the H275Y mutation was detected according to the CDC pyrosequencing protocol 5 with the following modifications: Qiagen’s PyroMark™ Q24 system was employed, and a final pyrosequencing primer concentration of 2·0 μm was used. Similarly, HA gene fragments were amplified according to the H275Y RT‐PCR parameters. 5 HA amplicons were analyzed on the PyroMark™ Q24 system following the CDC protocol for the detection of HA222 variants utilizing only the customized dispensation order. 6 , 7

Surveillance and virologic results

From April 2009 to February 2010, there were 60 deaths reported in Minnesota associated with 2009 H1N1, of which 53 (88%) had respiratory specimens available for testing. Adequate nucleic acid to perform pyrosequencing for H275Y mutational analysis was present in 39 (74%) fatal cases, of which 38 (97%) had wild‐type sequence (H275H) and 1 (3%) had the H275Y mutation. Adequate nucleic acid to perform pyrosequencing for HA‐222 was present in 43 (81%) fatal cases, of which 38 (88%) had wild‐type sequence only (D222D), 4 (9%) had mixed infection with quasi species of 2009 H1N1 strains identified with three sequences (D222D, D222N and D222G), and 1 (2%) had only D222G mutation.

The clinical specimen with the H275Y mutation identified by pyrosequencing was the same specimen that was identified with the D222G mutation by pyrosequencing. This was a bronchial alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid specimen collected on symptom day 19 that was tested within 48 hours of collection. Real‐time RT‐PCR testing of the BAL specimen was positive for influenza A, swine H1, and swine influenza A targets with C t values all <35. Pyrosequencing was performed on nucleic acid extract from the BAL specimen.

Case report

A 59‐year‐old male with systemic lupus erythematosus since 2006 presented in November 2009 with 10 days of dry cough and 48 hours of progressive dyspnea on exertion. He had no fever, myalgia, or lower‐extremity edema. He was taking 60 mg daily of prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and levofloxacin. He had been hospitalized briefly 1 month prior for heart failure symptoms and was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension and biopsy‐demonstrated glomerulonephritis. At discharge and several weeks subsequently, he had minimal pulmonary symptoms.

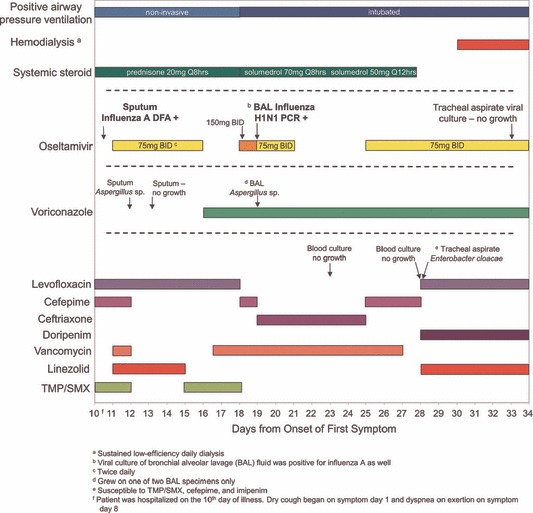

The patient was admitted on illness day 10 with bibasilar crackles but no jugular venous distension. He was admitted to the intensive care unit requiring noninvasive positive airway pressure. Chest X‐ray demonstrated bilateral lung infiltrates. His white blood cell count was 5·5 cells/μl (normal, 3·2–10·6), including 5·3 neutrophils/μl (normal, 1·3–7·0) and 0·08 lymphocytes/μl (normal, 0·8–3·1). Direct fluorescent antibody testing of a nasopharyngeal specimen was positive for influenza A, and oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily was started for 5 days (Figure 1). His respiratory status declined, and he was intubated on symptom day 18. Oseltamivir 150 mg twice daily for 1 day was restarted per gastric tube, followed by 75 mg twice daily. Computed tomography of the chest revealed bilateral ground glass densities and superimposed irregular nodules most pronounced in the lower lobes. A BAL was performed on symptom day 19 and tested for influenza rRT‐PCR at MDH Public Health laboratory. Bronchial alveolar lavage fluid was also sent for viral culture to a clinical laboratory that grew influenza A virus using centrifuged shell vial technique. This isolate was not available for further testing. The BAL fungal culture grew Aspergillus sp. His respiratory status declined with worsening pulmonary infiltrates, bilateral pneumothoraces, refractory hypoxemia, and worsening renal function requiring dialysis. Support was withdrawn on symptom day 34 and the patient expired. No autopsy was performed.

Figure 1.

Treatment and testing following hospitalization. The patient was hospitalized beginning on day 10 after onset of first respiratory symptoms. No influenza antiviral medication was administered prior to hospitalization.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical description of a patient with 2009 H1N1 virus infection identified with NA‐H275Y and HA‐D222G. Such mutations have been described in three other instances without clinical details. 8 This patient had multiple underlying medical conditions that increased the risk of severe complications from 2009 H1N1 virus infection. Bacterial co‐infection was not detected, but fungal culture of BAL fluid yielded Aspergillus. Aspergillus infection associated with severe 2009 H1N1 disease has been described in two other cases. 9

Oseltamivir resistance may have developed during treatment in this patient as has been previously described; however, initial infection with an oseltamivir‐resistant strain cannot be excluded. While there are documented instances of non‐sustained person‐to‐person transmission of 2009 H1N1 virus strains containing H275Y, these appear to be rare events. 10

It is possible that oseltamivir resistance may impact clinical outcomes particularly among patients with immunosuppression and prolonged influenza viral replication. 11 A comparison of patients infected with oseltamivir‐resistant versus susceptible strains found that immunosuppression was the only risk factor significantly associated with oseltamivir resistance. 12 Because of this increased risk of development of oseltamivir resistance during or after oseltamivir treatment, clinicians should consider the use of zanamivir as primary therapy for immunosuppressed patients with influenza, and especially for patients with suspected or 0‐confirmed oseltamivir resistance. 13 , 14

Recombinant clones of 1918 pandemic H1N1 virus with a hemagglutinin mutation at position 222 (225 in H3 numbering system) from aspartic acid to glycine were found to change viral tropism from alpha2‐6 sialic acids to dual tropism for alpha2‐3 and alpha2‐6 sialic acids, suggesting the potential importance of a single substitution at the receptor‐binding site of the hemagglutinin. 15 Recent reports have suggested a link between the HA‐D222G mutation in 2009 H1N1 virus infection with severe and fatal outcomes. 16

If the HA‐D222G mutation results in greater affinity for receptors with alpha2‐3 sialic acids found predominantly in the human lower respiratory tract, it is possible that a HA‐D222G subpopulation would be preferentially selected by lower respiratory tract sampling from a heterogeneous influenza pool, especially in persons with severe lower respiratory tract disease and with prolonged viral replication. In a recent study of paired nasal swab and BAL specimens, D222G mutants accounted for 40% of the lower respiratory tract viral population compared with only 10% in the upper respiratory tract. 17

Influenza virus mutations have also been identified more frequently among isolates obtained after growth in cell culture compared with primary clinical specimens, suggesting that replication of virus in tissue cell culture can lead to selection of virus variants with altered receptor specificity. 18 Therefore, it is essential that molecular testing for influenza viruses is performed on original specimens and not viral culture isolates to limit this possibility.

As this was not a study and with only a single isolate available for testing, it is not possible to ascertain whether the combination of NA‐H275Y and HA‐D222G mutations contributed to illness severity. This case illustrates the importance of further research regarding viral factors impacting severity. Future studies should prospectively collect the following specimens from patients for influenza testing by rRT‐PCR, genetic sequencing, and other molecular analyses: (i) multiple, serial respiratory specimens from close to illness onset or early in the clinical illness, prior to or at the time of initiation of antiviral therapy, following antiviral treatment, and later in the clinical course if possible; and (ii) paired (obtained at the same time) clinical specimens from both the upper and lower respiratory tract if possible, especially for critically ill patients. Sampling should be carried out for persons with mild uncomplicated influenza illness and for persons with severe complications requiring hospitalization and critical care management. Integration of clinical (including information on antiviral treatment), epidemiological, and virologic data in such comparative studies will facilitate interpretation and contribute to improved understanding of viral changes that might lead to severe clinical outcomes of influenza virus infection.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Fares Masannat, Avera McKennon University Hospital, Sioux Falls, SD. We thank Dr. Larisa Gubareva for important comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza . Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1708–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller RR, MacLean AR, Gunson RN, Carman WF. Occurrence of haemagglutinin mutation D222G in pandemic influenza A(H1N1) infected patients in the West of Scotland, United Kingdom, 2009–10. Euro Surveill 2010; 15(16):pii=19546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chutinimitkul S, Herfst S, Steel J et al. Virulence‐associated substitution D222G in hemagglutinin of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus affects receptor binding. J Virol 2010; 84:11802–11813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . CDC protocol of realtime RTPCR for influenza A(H1N1) revision 2. 2009; Available at http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/CDCRealtimeRTPCR_SwineH1Assay‐2009_20090430.pdf (cited 2 August 2010).

- 5. World Health Organization . CDC pyrosequencing assay to detect H275Y mutation in the neuraminidase of novel A (H1N1) viruses. 2009; Available at http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/NA_DetailedPyrosequencing_20090513.pdf (Accessed 2 August 2010).

- 6. Deyde VM, Sheu TG, Trujillo AA et al. Detection of molecular markers of drug resistance in 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) viruses by pyrosequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:1102–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levine M, Sheu TG, Gubareva LV, Mishin VP. Detection of hemagglutinin variants of the pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 virus by pyrosequencing. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49:1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Preliminary review of D222G amino acid substitution in the haemagglutinin of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 viruses. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2010; 85:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lat A, Bhadelia N, Miko B, Furuya EY, Thompson GR III. Invasive Aspergillosis after Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16:971–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Oseltamivir‐resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis – North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58:969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tramontana AR, George B, Hurt AC et al. Oseltamivir resistance in adult oncology and hematology patients infected with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16:1068–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calatayud L, Lackenby A, Reynolds A et al. Oseltamivir‐resistant pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in England and Scotland, 2009–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1807–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D et al. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza – recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2011; 60:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . WHO guidelines for pharmacological management of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 and other influenza viruses. Revised February 2010. Available at http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/h1n1_guidelines_pharmaceutical_mngt.pdf. [PubMed]

- 15. Stevens J, Blixt O, Glaser L et al. Glycan microarray analysis of the hemagglutinins from modern and pandemic influenza viruses reveals different receptor specificities. J Mol Biol 2006; 355:1143–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan PK, Lee N, Joynt GM et al. Clinical and virological course of infection with haemagglutinin D222G mutant strain of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. J Clin Virol 2011; 50:320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baldanti F, Campanini G, Piralla A et al. Severe outcome of influenza A/H1N1/09v infection associated with 222G/N polymorphisms in the haemagglutinin: a multicentre study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Govorkova EA, Matrosovich MN, Tuzikov AB et al. Selection of receptor‐binding variants of human influenza A and B viruses in baby hamster kidney cells. Virology 1999; 262:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]