Abstract

The effects of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on daily weight gain, lipid profile and atherogenic indices of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet was studied. The control group was given normal feed while the other three groups received 50 g egg yolk/kg feed. The extract was orally administered daily at 150 and 200 mg/kg body weight; while the test control and control groups received appropriate volumes of water by the same route. On gas chromatographic analysis of the aqueous crude extract, the phytosterol and tannins fractions contained 100 % of β-sitosterol and tannic acid respectively. The mean daily weight gain of the test control group was higher though not significantly, than those of the other groups. The plasma total cholesterol levels, cardiac risk ratio and atherogenic coefficient of the test control group was significantly higher (P<0.05) than those of the test groups, but not significantly higher than that of the control group. The plasma low density lipoprotein and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of the test control group was significantly higher (P<0.05) than those of the control and test groups. The plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol of the test control group was significantly lower (P<0.05) than that of the control group, but not significantly lower than those of the test groups. There were no significant differences in the plasma triglyceride and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and the atherogenic index of plasma of all the groups. These results indicate a dose-dependent hypocholesterolemic effect of the extract, thus suggesting a likely protective role of the extract against the development of cardiovascular diseases. It also revealed the presence of pharmacologically active agents in the leaves.

Keywords: atherogenic indices, lipid profile, Sansevieria senegambica, beta-sitosterol, tannic acid

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the world (Thomas, 2007[33]). Development and progression of cardiovascular disease is linked to the presence of risk factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus (Martirosyan et al., 2007[26]). It is known that cholesterol is an indicator of increased risk of heart attack, stroke, etc. (Yusuf et al., 2001[38]). A consistent body of evidence from large clinical trials has established beyond doubt that lipid lowering can reduce the incidence of coronary events and stroke in a broad spectrum of individuals (Libby, 2001[23]). Therefore, any nutritional and pharmacologic intervention that improves or normalizes abnormal lipid metabolism may be useful for reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases (Zicha et al., 1999[39]; Shen, 2007[31]). Several drugs are at present, available for the management of dyslipidemia. However, there is renewed interest in the use of herbal products.

Sansevieria senegambica Baker (Family Agavaceae or Ruscaceae) is an ornamental plant (United States Department of Agriculture, 2008[36]) used in traditional health practice in southern Nigeria for treating bronchitis, inflammation, coughs, boils and hypertension. It is also used in arresting the effects of snake bites, as well as in compounding solutions used as hair tonics. The anti-diabetic (Ikewuchi, 2010[17]) and weight reducing (Ikewuchi et al., 2011[19]) effects, as well as the ability of the aqueous extract of the leaves to moderate plasma electrolytes (Ayalogu et al., 2011[6]), have been reported. Gas chromatographic analysis of the leaves revealed the presence of alkaloids, allicins, glycosides and saponins (Ikewuchi et al., 2011[18]). The present study investigated the effect of aqueous extract of the leaves on weight, plasma lipid profile and atherogenic indices in rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet, with a view to unveiling any likely cardioprotective potential.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of plant extract

Samples of fresh Sansevieria senegambica plants (Figure 1(Fig. 1)) were procured from a horticultural garden at the University of Port Harcourt's Abuja campus, and from behind the Ofrima complex, University of Port Harcourt, in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. After due identification at the University of Port Harcourt Herbarium, Port Harcourt, Nigeria, the identity was confirmed authenticated by Dr. Michael C. Dike of Taxonomy Unit, Department of Forestry and Environmental Management, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria; and Mr. John Ibe, the Herbarium Manager of the Forestry Department, National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI), Umuahia, Nigeria. The plants were cleaned of soil and the leaves were removed, oven dried at 55 °C and ground into a powder. The resultant powder was soaked in hot, boiled distilled water for 12 h, after which the resultant mixture was filtered and the filtrate was stored in a refrigerator for subsequent use. A known volume of this extract was evaporated to dryness, and the weight of the residue used to determine the concentration of the filtrate, which was in turn used to determine the dose for administration of the extract to the test animals. The resultant residue was used for the phytochemical study, to determine its phytosterol and tannin compositions. The percentage recovery of the crude aqueous extract was 26.40%

Figure 1. Sansevieria senegambica Baker.

Determination of the phytochemical content of the crude aqueous leaf extract

Calibration, identification and quantification

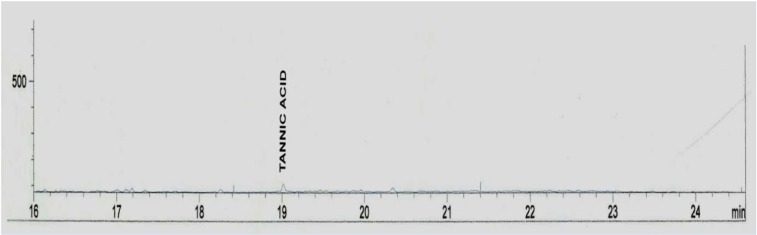

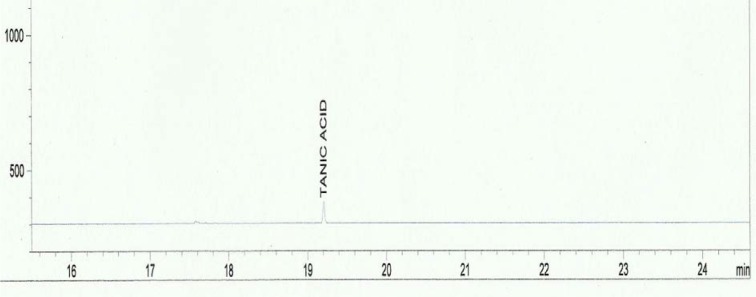

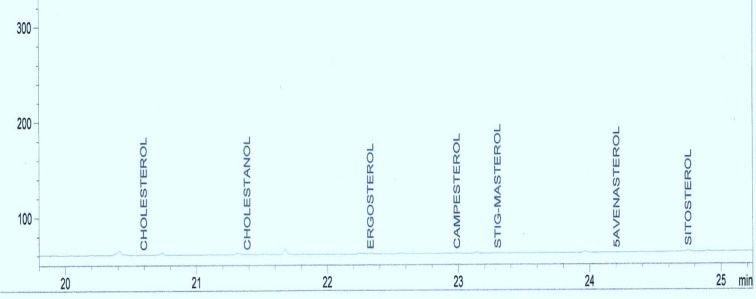

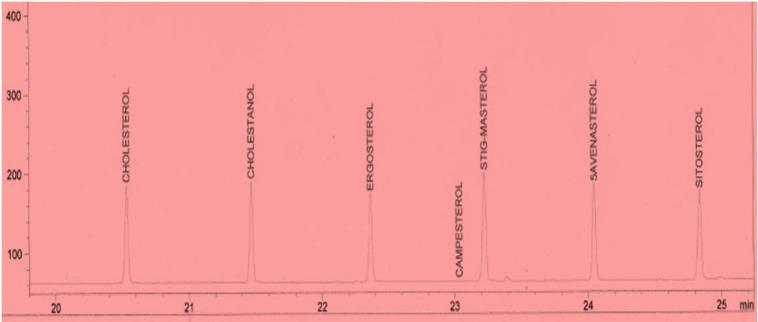

Standard solutions were prepared in methanol for tannins and methylene chloride for phytosterols. The linearity of the dependence of response on concentration was verified by regression analysis. Identification was based on comparison of retention times and spectral data with standards. Quantification was performed by establishing calibration curves for each compound determined, using the standards. Samples chromatograms of the extract are shown in Figures 2-5(Fig. 2)(Fig. 3)(Fig. 4)(Fig. 5).

Figure 2. Chromatogram of the tannin composition of the aqueous extract of Sansevieria senegambica leaves.

Figure 3. Chromatogram of the tannin standard.

Figure 4. Chromatogram of the phytosterol composition of the aqueous extract of Sansevieria senegambica leaves.

Figure 5. Chromatogram of the phytosterol standard mixture.

Determination of phytosterol composition

Extraction of oil was carried out according to AOAC method 999.02 (AOAC International, 2002[4]), while the analysis of sterols was carried out according to AOAC method 994.10 (AOAC International, 2000[3]). This involved extraction of the lipid fraction from homogenized sample material, followed by alkaline hydrolysis (saponification), extraction of the non-saponifiables, clean-up of the extract, derivatisation of the sterols, and separation and quantification of the sterol derivatives by gas chromatography (GC) using a capillary column. Chromatographic analyses were carried out on an HP 6890 (Hewlett Packard, Wilmington, DE, USA), GC apparatus, fitted with a flame ionization detector (FID), and powered with HP Chemstation Rev. A 09.01 (1206) software, to quantify and identify compounds. The column was HP INNOWax Column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness). The inlet and detection temperatures were 250 and 320 °C. Split injection was adopted with a split ratio of 20:1. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas. The hydrogen and compressed air pressures were 22 psi and 35 psi. The oven was programmed as follows: initial temperature at 60 °C, first ramping at 10 °C/min for 20 min, maintained for 4 min, followed by a second ramping at 15 °C/min for 4 min, maintained for 10 min.

Determination of tannin composition

Extraction was carried out according to the method of Luthar (1992[25]). The tannin fraction of the crude aqueous extract above was extracted with methanol and subjected to gas chromatographic analysis. Chromatographic analyses were carried out on an HP 6890 (Hewlett Packard, Wilmington, DE, USA), GC apparatus, fitted with a flame ionization detector (FID), and powered with HP Chemstation Rev. A 09.01 (1206) software, to quantify and identify compounds. The column was HP 5 Column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness). The inlet and detection temperatures were 250 and 320 °C. Split injection was adopted with a split ratio of 20:1. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas. The hydrogen and compressed air pressures were 28 psi and 40 psi. The oven was programmed as follows: initial temperature at 120 °C, followed by ramping at 10 °C/min for 20 min.

Experimental design for the egg yolk supplementation

Male Wistar albino rats (weighing 190 g-205 g at the start of the study) were obtained from the animal house of the Department of Physiology, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus. All the experiments were conducted in accordance with the internationally accepted principles for laboratory animal use and care as found in the European Community Guidelines (EEC Directive of 1986; 86/609/EEC). The rats were sorted into four groups of five animals each, so that the average weight difference was ≤ 1.5 g. The animals were housed in plastic cages in the animal house of the Department of Biochemistry, University of Port Harcourt. After a one-week acclimatization period on guinea growers mash (Port Harcourt Flour Mills, Port Harcourt, Nigeria), the treatment commenced and lasted for two weeks. The control group was given normal feed while the three test groups received 50 g egg yolk/kg feed. Test group 1 (SS1) received 150 mg/kg and test group 2 (SS2) received 200 mg/kg body weight of the Sansevieria senegambica leaf extract daily by intra-gastric gavage. The test control, reference treatment (reference) and control groups received equivalent volumes of water by the same route. The dosage of administration of the extract was adapted from Ikewuchi (2010[17]) and Ayalogu et al. (2011[6]), while the two weeks egg yolk supplementation is a modification of the two week 5% loading reported by Agbafor and Akubugwo (2007[2]). The animals were allowed food and water ad libitum. At the end of the treatment period the rats were weighed, fasted overnight and anaesthetized by exposure to chloroform. While under anesthesia, they were painlessly sacrificed and blood was collected from each rat into heparin sample bottles. Whole blood was immediately used to determine the triglyceride levels, using multiCareinTM test strips and glucometer (Biochemical Systems International, Arezzo, Italy). The heparin anti-coagulated blood samples were centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min, after which their plasma was collected and stored for subsequent analysis.

Determination of the plasma lipid profiles/atherogenic indices

Plasma triglyceride concentration was determined using multiCareinTM triglyceride strips and glucometer (Biochemical Systems International, Arezzo, Italy). Plasma total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (TC and HDLC) concentrations were assayed enzymatically with Randox commercial test kits (Randox Laboratories Ltd., Crumlin, England, UK). Plasma low density (LDL) and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol concentrations were calculated using the Friedewald equation (Friedewald et al., 1972[16]) as follows:

while the plasma non-HDL cholesterol concentration was determined as reported by Brunzell et al. (2008[10]):

The atherogenic indices were calculated as earlier reported by Ikewuchi and Ikewuchi (2009[21][20]), using the following formulae:

Statistical analysis of data

All values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. The values of the variables were analyzed for statistically significant differences using the Student's t-test, with the help of SPSS Statistics 17.0 package (SPSS Inc., Chicago Ill). P<0.05 was assumed to be significant. Graphs were drawn using Microsoft Office Excel, 2010 software.

Results

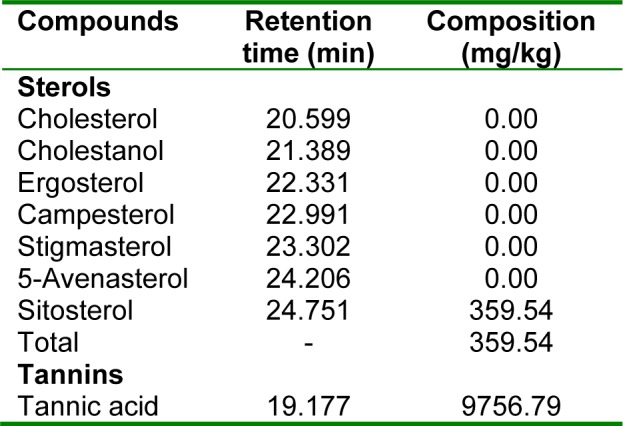

Table 1(Tab. 1) shows the phytosterol and tannin composition of the aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica. The sterol extract consisted 100 % of sitosterol, while the tannin extract consisted 100 % of tannic acid.

Table 1. Table 1: Phytosterol and tannin composition of the aqueous extract of Sansevieria senegambica leaves.

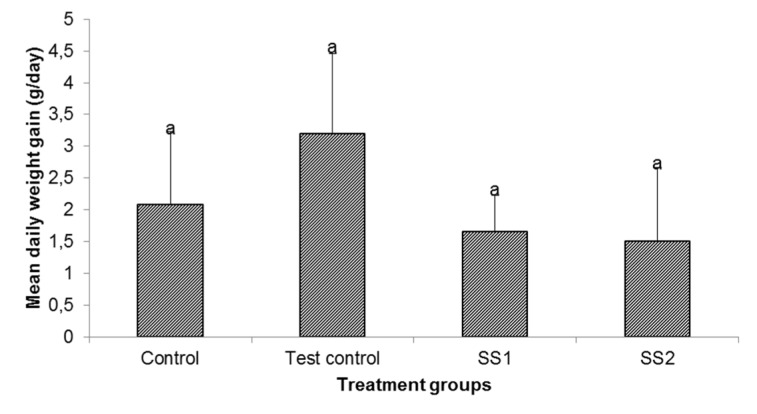

The effect of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on the daily weight gain of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet is shown in Figure 6(Fig. 6). The mean daily weight gain of the test control group was higher though not significantly, than those of the other groups.

Figure 6. Effect of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on daily weight gain of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet.

Values are mean ± SD, n=5, per group

aValues with the same superscripts were not significantly different at P<0.05.

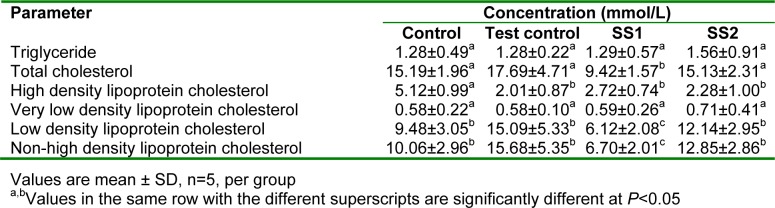

Table 2(Tab. 2) shows the effects of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on the plasma lipid profiles of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet. There were no significant differences in the plasma triglyceride and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations of all the groups. The plasma total cholesterol levels of the test control group was significantly lower (P<0.05) than that of SS1, but not significantly lower than those of the control and SS group. The plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of the test groups were higher (though not significantly) than that of the test control group, but significantly (P<0.05) lower than the control. The plasma low density lipoprotein and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of the test control group was significantly higher (P<0.05) than that of SS1, but not significantly higher than those of the control and SS2 group.

Table 2. Effect of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on the plasma lipid profiles of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet.

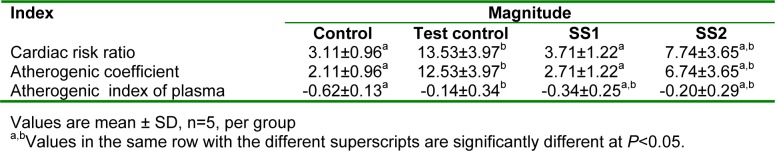

The effect of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on atherogenic indices of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet is given in Table 3(Tab. 3). The cardiac risk ratio and atherogenic coefficient of the test control group was significantly higher (P<0.05) than that of SS1, but not significantly higher than those of the control and SS2 groups. The atherogenic index of plasma of the test control group was significantly higher (P<0.05) than the control, but not significantly higher than those of the other groups.

Table 3. Effect of an aqueous extract of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica on atherogenic indices of rats fed egg yolk supplemented diet.

Discussion

Studies have shown that weight reduction is one of the means of alleviating coronary risk incidence, dyslipidemia, hypertension and obesity (Mertens and Van Gaal, 2000[27]; Trussell et al., 2005[35]; Krauss et al., 2006[22]), and is one of the strategies for increasing low high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults, 2002[15]; Assmann and Gotto Jr, 2004[5]). Therefore, the reduction in weight gain produced by the extract signifies its cardioprotective potential. This lower mean daily weight gain observed in the animals administered the extract, may be due to the diuretic effect of the leaves, produced by the saponins present in them (Soetan, 2008[32]).

The effects of the extract were dose dependent, with the 150 mg/kg dose being more effective (Tables 2(Tab. 2) and 3(Tab. 3)).The extract produced low plasma total cholesterol levels in the treated rats. This may be cardioprotective, since elevated plasma total cholesterol level is a recognized and well-established risk factor for developing atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases (Ademuyiwa et al., 2005[1]).

Reduction in plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration has been considered to lower the risk of coronary heart disease (Rang et al., 2005[30]; Shen, 2007[31]). In this study, a significantly lower plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol level was produced by the extract, indicating its likely cardioprotective potential. Many studies have shown that non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol is a better predictor of cardiovascular disease risk than is low density lipoprotein cholesterol (Shen, 2007[31]; Liu et al., 2005[24]; Pischon et al., 2005[29]). Therefore, the significantly lower plasma non high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels observed in the test groups indicate the ability of the extract, to reduce cardiovascular risk.

This cholesterol lowering effect of the extract may be due to its content of β-sitosterol and tannic acid (Table 1(Tab. 1)), which are known to have cholesterol lowering and atheroprotective activity (Dillard and German, 2000[12]; Piironen et al., 2000[28]; Berger et al., 2004[8]; Basu et al.,2007[7]). This hypocholesterolemic activity of the extract may be due to the presence of saponin in the leaves (Ikewuchi et al., 2011[18]). Saponins are reported to assist in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases (Topping et al., 1980[34]) by lowering plasma cholesterol concentrations through the excretion of cholesterol directly or indirectly as bile acids (Soetan, 2008[32]; European Food and Safety Authority, 2009[14]; Ceyhun Sezgin and Artık, 2010[11]). Thus, anyone or a combination of some or all of the above mentioned components could have been responsible for the hypocholesterolemic effect of the extract, observed in this study.

The atherogenic indices are strong indicators of the risk of heart disease. The risk of developing cardiovascular disease increases with increases in the values of these indices, and vice versa (Martirosyan et al., 2007[26]; Brehm et al., 2004[9]; Dobiásová, 2004[13]; Usoro et al., 2006[37]). Therefore, low atherogenic indices are protective against coronary heart disease (Usoro et al., 2006[37]). In this study, the extract produced significantly lower cardiac risk ratio and atherogenic coefficient.

Conclusion

These results indicate a dose dependent hypocholesterolemic effect of the extract, thus suggesting a likely protective role of the extract against dyslipidemia and the development of cardiovascular diseases. It also revealed the presence of bioactive agents in the extract.

References

- 1.Ademuyiwa O, Ugbaja RN, Idumebor F, Adebawo O. Plasma lipid profiles and risk of cardiovascular disease in occupational lead exposure in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Lipids Health Dis. 2005;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agbafor KN, Akubugwo EI. Hypocholesterolaemic effect of ethanolic extract of fresh leaves of Cymbopogon citrates (lemongrass) Afr J Biotech. 2007;6:596–598. [Google Scholar]

- 3.AOAC, Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Cholesterol in foods. Direct saponification-gas chromatographic method. AOAC Official Method 994.10. Gaithersberg (USA): AOAC International; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.AOAC, Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Oil in seeds. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) method. AOAC Official Method 999.02. Gaithersberg (USA): AOAC International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assmann G, Gotto AM., Jr HDL cholesterol and protective factors in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109(Suppl III):III–8–III. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131512.50667.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayalogu EO, Ikewuchi CC, Onyeike EN, Ikewuchi JC. Effects of an aqueous leaf extract of Sansevieria senegambica Baker on plasma biochemistry and haematological indices of salt-loaded rats. S Afr J Sci. 2011;107(11/12) Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v107i11/12.481. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu SK, Thomas JE, Acharya SN. Prospects for growth in global nutraceutical and functional food markets: A Canadian perspective. Australian J Basic Appl Sci. 2007;1:637–649. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger A, Jones PJH, Abumweis SS. Plant sterols: factors affecting their efficacy and safety as functional food ingredients. Lipids Health Dis. 2004;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brehm A, Pfeiler G, Pacini G, Vierhapper H, Roden M. Relationship between serum lipoprotein ratios and insulin resistance in obesity. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2316–22. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.037556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, et al. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1512–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceyhun Sezgin AE, Artık N. Determination of saponin content in Turkish Tahini Halvah by using HPLC. Adv J Food Sci Technol. 2010;2:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dillard CJ, German JB. Phytochemicals: nutraceuticals and human health. J Sci Food Agric. 2000;80:1744–56. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobiásová M. Atherogenic index of plasma (log (triglyceride/HDL-Cholesterol)): Theoretical and practical implications. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1113–1115. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Food and Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain on a request from the European Commission on saponins in Madhuca Longifolia L. as undesirable substances in animal feed. EFSA J. 2009;979:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III), Final Report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Friedrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikewuchi CC. Effect of aqueous extract of Sansevieria senegambica Baker on plasma chemistry, lipid profile and atherogenic indices of alloxan treated rats: Implications for the management of cardiovascular complications in diabetes mellitus. Pac J Sci Technol. 2010;11:524–531. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikewuchi CC, Ikewuchi JC, Ayalogu EO, Onyeike EN. Quantitative determination of alkaloid, allicin, glycoside and saponin constituents of the leaves of Sansevieria senegambica Baker by gas chromatography. Res J Sci Technol. 2011;3:308–312. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikewuchi CC, Ikewuchi JC, Ayalogu EO, Onyeike EN. Weight reducing and hypocholesterolemic effect of aqueous leaf extract of Sansevieria senegambica Baker on sub-chronic salt-loaded rats: Implication for the reduction of cardiovascular risk. Res J Pharmacy Technol. 2011;4:725–729. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikewuchi JC, Ikewuchi CC. Alteration of plasma lipid profile and atherogenic indices of cholesterol loaded rats by Tridax procumbens Linn: Implications for the management of obesity and cardiovascular diseases. Biokemistri. 2009;21(2):95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikewuchi JC, Ikewuchi CC. Alteration of plasma lipid profiles and atherogenic indices by Stachytarpheta jamaicensis L. (Vahl) Biokemistri. 2009;21(2):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krauss RM, Blanche PJ, Rawlings RS, Fernstrom HS, Williams PT. Separate effects of reduced carbohydrate intake and weight loss on atherogenic dyslipidemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1025–31. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Libby P. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of the acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2001;104:365–372. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.365. Available from: http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/104/3/365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J, Sempos C, Donahue R, Dorn J, Trevisan M, Grundy SM. Joint distribution of non-HDL and LDL cholesterol and coronary heart disease risk prediction among individuals with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1916–1921. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luthar Z. Polyphenol classification and tannin content of buckwheat seeds (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) Fagopyrum. 1992;12:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martirosyan DM, Miroshnichenko LA, Kulokawa SN, Pogojeva AV, Zoloedov VI. Amaranth oil application for heart disease and hypertension. Lipids Health Dis. 2007;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mertens IL, Van Gaal LF. Overweight, obesity, and blood pressure: The effects of modest weight reduction. Obesity Res. 2000;8:270–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piironen V, Lindsay DG, Miettinen TA, Toivo J, Lampi A-M. Plant sterols: biosynthesis, biological function and their importance to human nutrition. J Sci Food Agric. 2000;80:939–966. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pischon T, Girman CJ, Sacks FM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB. Non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol and apolipoprotein B in the prediction of coronary heart disease in men. Circulation. 2005;112:3375–3383. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.532499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rang HP, Dale DM, Ritter JM, Moore PK. Pharmacology. 5th. India: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen GX. Lipid disorders in diabetes mellitus and current management. Curr Pharmaceut Anal. 2007;3:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soetan KO. Pharmacological and other beneficial effects of antinutritional factors in plants - a review. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7:4713–4721. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas GS. President’s message: The global burden of cardiovascular disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14:621–662. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Topping DL, Storer GB, Calvert GG. Effects of dietary saponins on faecal bile acids and neutral sterols, plasma lipid and lipid turnover in the pig. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:783–786. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trussell KC, Hinnen D, Gray P, Drake-Nisly SA, Bratcher KM, Ramsey H, et al. Weight loss leads to cost savings and improvement in metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Spectrum. 2005;18(2):77–79. [Google Scholar]

- 36.United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) GRIN taxonomy for plants (database on the Internet) 2008. [2008 July 23]. Available from: http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?33057.

- 37.Usoro CAO, Adikwuru CC, Usoro IN, Nsonwu AC. Lipid profile of postmenopausal women in Calabar, Nigeria. Pak J Nutr. 2006;5(1):79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part I: General considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104:2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zicha J, Kunes J, Devynck MA. Abnormalities of membrane function and lipid metabolism in hypertension: a review. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:315–331. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]