Abstract

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has gained widespread application for many biomedical applications, yet the traditional array of contrast agents used in incoherent imaging modalities do not provide contrast in OCT. Owing to the high biocompatibility of iron oxides and noble metals, magnetic and plasmonic nanoparticles, respectively, have been developed as OCT contrast agents to enable a range of biological and pre-clinical studies. Here we provide a review of these developments within the past decade, including an overview of the physical contrast mechanisms and classes of OCT system hardware addons needed for magnetic and plasmonic nanoparticle contrast. A comparison of the wide variety of nanoparticle systems is also presented, where the figures of merit depend strongly upon the choice of biological application.

Index Terms: Contrast agents, optical coherence tomography, plasmonic nanoparticles, superparamagnetic iron oxides, magnetomotive

I. Introduction

Optical coherence tomography (OCT), first reported in 1991 [1], has become widely adapted particularly for retinal imaging [2] and other ophthalmic applications [3], with emerging applications in coronary artery imaging [4], surgical guidance [5], and endoscopic imaging of the gastro-intestinal tract [6, 7] and upper airways [8]. OCT operates on the principle of low-coherence gating to provide a depth-resolved image of light scattering within biological tissue [9]. Light scattering, in general, is caused by refractive index heterogeneities on the scale of the wavelength of the probing light (λ), which means that cells and subcellular objects such as nuclei and mitochondria tend to provide OCT contrast [10]. This mechanism of contrast allows one to distinguish different cell layers within the human retina [11], sites of atherosclerotic plaque within the coronary artery [12], as well as blood flow for angiography [13]. However, it is also somewhat limited for applications such as cancer detection, where the speckled features of normal and cancer tissue can appear very similar [14].

In order to widen the application space of OCT, there has been much effort to develop contrast agents and associated imaging methods [15, 16]. Because OCT only senses coherently backscattered light, it cannot detect light from traditional incoherent (fluorescent) probes used widely in microscopy. To develop an effective contrast agent probe for OCT, it must provide a signal that is distinct from that of the tissue surrounding it. In this paper, we discuss two highly successful classes of contrast agents: magnetic contrast agents that, when interrogated with a magnetic field, provide a unique motion signal, and plasmon-resonant contrast agents that exhibit extremely high optical cross-sections, offering a variety of optical effects that can be exploited for sensing within tissue. In many applications such as cancer diagnostics, effective targeting of these agents by bioconjugation or the enhanced permeability and retention effect is needed, and the reader is directed to reviews for more detailed information about targeting moieties [17, 18]. Also, magnetic and plasmonic nanoparticles are by no means the only methods for OCT contrast enhancement, and the reader is directed to review articles that cover a broader range of development [16, 19, 20].

II. Magnetomotive OCT: Theory and Practice

The magnetic volume susceptibility at zero magnetic field, χ(B=0), quantifies the rate of change in the magnetization of a material as the magnetic flux density, B, is increased. Biological tissues are relatively non-magnetic, that is, χ is on the order of −10−5, and is dominated by that of water [21]. In comparison, magnetic iron oxides (MIOs) can exhibit χ ~ 1, or 105 stronger than that of tissue. Thus, χ can provide an effective contrast mechanism for magnetic particle imaging. Because OCT is particularly sensitive to motion, with phase-resolved OCT providing displacement resolution in the picometer range [22], magnetomotive OCT (MMOCT) exploits the motion of magnetic nanoparticles induced by an applied magnetic field (Fig. 1). This is known as the magnetic gradient force effect:

| (1) |

where F is the force acting on the MIO with susceptibility χ within its surrounding medium, χmed, B is the magnetic flux density, V is the MIO volume, and μ0 is the vacuum permeability. Interestingly, the force acting on particles with χ>0 (paramagnetic) always points toward the electromagnet, irrespective of the polarity of the B field.

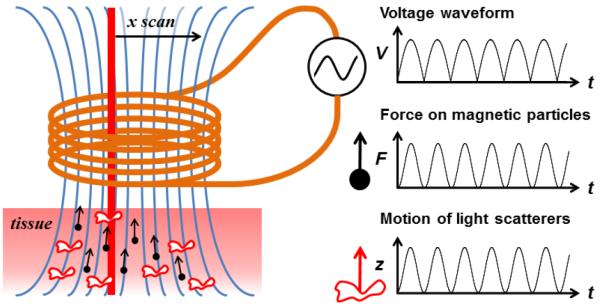

Fig. 1.

Concept diagram of sinusoidal MMOCT. Tissue containing MNPs (black dots) is placed in the fringe field (blue lines) of a solenoid, while the OCT imaging beam scans through its bore. A square-root sinusoidal voltage applied to the solenoid produces a pure sinusoidal force on MNPs directed along the field gradient. OCT detects the resulting axially-directed motion (z) of light-scattering structures within the tissue that are mechanically coupled to the MNP motion.

Magnetic iron oxides are a natural choice as MMOCT contrast agents because iron is already metabolized within the human body in large quantities, and iron oxide nanoparticles have already been in use as MRI contrast agents with few side effects [23]. There are two magnetic crystalline forms of iron oxide: γ-Fe2O3 (maghemite) and Fe3O4 (magnetite), which can often be produced by the same synthesis methods and can be difficult to distinguish between due to similar X-ray diffraction and magnetic properties [24]. Thermodynamically, magnetite slowly oxides to maghemite, then eventually to hematite (α-Fe2O3, or rust) [25].

Interestingly, the figures of merit for an OCT contrast agent are different than for MRI contrast. In MRI, MIOs must be small in order to maximize surface area contact with adjacent water molecules, whose magnetic resonance is shifted by the local particle magnetization [26]. In OCT, MIOs must maximize their motion via Eqn. (1), which suggests a large particle volume, V. However, there are two practical limits to the size of MNPs: a) if particles are too large to be administered to the imaging target (e.g., into small capillaries or by diffusion through tissue), and b) if particles become significantly ferromagnetic such that they irreversibly aggregate under an applied magnetic field. Superparamagnetic iron oxides (SPIOs) are typically desired because they maintain strong magnetic susceptibility while lacking remanent magnetization. Thus, MMOCT contrast agents tend to have MIO cores between ~10-50nm, although larger particle clusters [27] or novel ferrofluid-filled microspheres [28] have been developed for certain applications.

Importantly, MIOs are optically absorbing, appearing almost completely black in color. Thus, it is not possible to use OCT to directly sense their magnetic gradient-driven motion (magnetomotion). It is only in their coupling with adjacent light scattering structures within the tissue that they can be detected (Fig. 1). MIOs free in solution (such as a blood vessel) will exhibit little OCT motion contrast in comparison to MNPs elastically bound to a target within the tissue (such as a targeted cell receptor, or by being internalized into a subcellular compartment). Tissue elasticity also provides an important restoring force when the B-field is switched off, returning the tissue to its original state of deformation. This allows for the application of modulated B-fields to be used to measure several cycles of repeated deformation, improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), analogous to lock-in detection.

Despite the ability to attain arbitrarily large SNR with repeated measurements, there is a fundamental sensitivity limit to MMOCT given by the ratio of the medium to the particle magnetic susceptibility [29]:

| (2) |

which corresponds to an MIO density on the order of ρ = 8μg/g for a typical MIO. This is the MIO concentration where the force from the diamagnetic components of the tissue (which push away from the magnet) exactly balance the force on the particles, and there is no net motion. Below this limit, the tissue is actually pushed away from the magnet, which can be seen particularly if the magnetic field being used is too high. In fact, in [29, 30], it has been shown that there is a decreasing effect of MMOCT contrast with increasing magnetic field if the field is above that needed for the MIOs to reach their saturation magnetization. This is somewhat counter-intuitive, and can be understood by the fact that the diamagnetic tissue magnetization (which is negative) continues to grow with B even after the MIO are saturated, eventually cancelling out the MIO magnetization. In the other extreme, if the B-field is too low, the MIO motion will be too minute to detect; thus, a sweet spot should be determined depending upon the target MIO concentration for the given application and phase noise of the OCT system; this sweet spot is typically just a little below the saturation field, which for MIOs is ~0.1 T.

The most challenging aspect of an MMOCT system is constructing an appropriate magnetic field delivery system. While some researchers have opted for commercially-available pointed-core solenoids which provide an extremely strong B field gradient at their tip, this requires illuminating the sample from the opposite direction, limiting studies to thin samples. In comparison, open-air designs such as in Fig. 1 permit an arbitrarily thick sample to be assessed, although do require higher currents to compensate for the lack of a solenoid core material, and thus will need to be water-jacketed to dissipate heat. The most expensive component is typically the programmable power supply (~100-250W), although a unipolar supply can save cost since MNPs will always be pulled in the same direction irrespective of polarity (Eq. 1).

Tissue mechanics play an important role in determining the MMOCT sensitivity and imaging speed. The displacement is inversely proportional to the tissue elastic modulus, and thus stiffer tissues will provide lower MMOCT contrast. At the same time, tissue viscoelasticity will slow the response time between the application of the force and the resulting displacement, limiting the maximum frequency that the B-field can be modulated (in practice, typically <100 Hz). Use of these lower frequencies avoids heating that occurs in techniques such as magnetic hyperthermia, where MIOs are modulated typically at >100 kHz to achieve significant heating effects [31]. In sinusoidally modulated MMOCT where the B-field is modulated several cycles per transverse position, this limits the accessible imaging acquisition time to several seconds. The new generation of high frame rate OCT systems (>100 fps) are currently allowing for MMOCT to be performed by collecting several frames (or volumes [32]) per B-field cycle, and thus frame rates nearing video rate are now possible.

It should be noted that there are a variety methods for performing MMOCT that are not necessarily subject to all of the discussion above, such as a two-coil system for MNP contrast in fluids [33], and the use of pulsed, rather than sinusoidal, B-fields [34]. Also, related platforms for imaging, including optical Doppler tomography (ODT), optical coherence elastography (OCE), and optical coherence microscopy (OCM) have been employed with magnetomotive contrast. These will be discussed in more detail in Section V.

III. Plasmonic Nanoparticle-based contrast with OCT: Theory and Practice

Surface plasmons are a collective excitation of electrons that oscillate across the surface of metals. In nanoparticles, these plasmons are confined to a small area and can become resonantly excited by light, either absorbing or re-emitting the light with high efficiency. In particular, only the noble metals gold and silver exhibit surface plasmon resonances (SPRs) in the visible spectrum, with gold being the only material offering SPRs in the near-infrared (NIR) wavelength regime typically used for OCT.

The fact that gold is a noble metal is also fortuitous for biomedical applications; gold is chemically inert and has been used as a medicine since ancient times [35], although caution should be taken to ensure that the surface charge does not induce cytotoxicity [36].

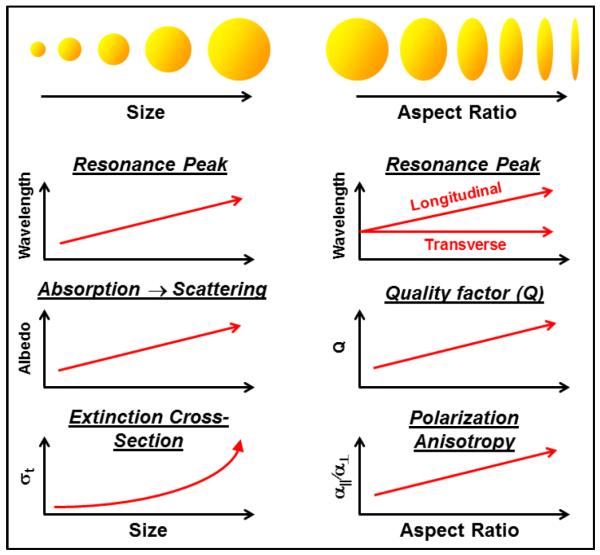

The SPR property of gold nanoparticles (GNPs) offers a unique opportunity to tailor contrast agents for OCT, as summarized conceptually in Fig. 2. For gold nanospheres, the SPR peak wavelength shifts gradually from ~535 nm to 635 nm for particles from 20 nm to 140 nm, respectively [37]. To access longer wavelengths, shaped particles such as ellipsoids (or, in practice, nanorods) are used which split the resonance modes along the principle axes of the particle. In the case of gold nanorods, aspect ratios of 2.4 to 5.6 provide longitudinal SPRs from ~650 nm to 950 nm, respectively [38].

Fig. 2.

General trends in the optical properties of gold nanospheres and prolate ellipsoids as a function of size and aspect ratio, respectively. The various contrast methods (SOCT, PTOCT, and DOCT) each have different figures of merit that dictate different particle sizes and shapes.

In addition to nanorods, GNPs with more complex geometries, like nanocages [39], nanorings [40] and nanoshells [41], also offer largely tunable spectral ranges. This is useful in multichannel measurements as seen with polarization-sensitive OCT [42] and SOCT [43]. Furthermore, shifting SPRs toward shorter wavelengths tailors the GNPs for use with higher-resolution OCT systems. Conversely, shifting the SPR toward longer wavelengths tailors them for OCT systems with larger penetration depths. This makes GNPs attractive for use with different systems depending upon the application.

A very important consideration is whether the SPR is predominantly light-absorbing or light-scattering in nature. Smaller particles are absorbing, with a transition to scattering-dominance at ~100 nm in size [44]. Thus, applications such as photothermal OCT (PTOCT), which requires high light absorption to generate heat, will tend to prefer smaller GNPs, while diffusion OCT (DOCT) exploits dynamic light scattering and prefers larger GNPs. Spectroscopic OCT (SOCT) can, in theory, be designed to sense either wavelength-dependent absorption or scattering, although in practice tends to employ absorption due to the already high scattering coefficient of tissue. Importantly, the optical extinction coefficient scales with the particle volume, V, in the absorbing regime, and V2 in the scattering regime [45], such that increasing particle size can rapidly increase optical detection. However, this must be balanced against the needs for smaller particles that can be effectively delivered to the biological target of interest.

An important consideration for SOCT is the quality factor (Q) of the SPR, as higher Q will provide a stronger wavelength-dependence, as well as the potential for multi-channel detection schemes. The Q of gold nanorods in particular has been established to be superior to gold spheres [46]. Another property of GNPs is polarization anisotropy, e.g., the ratio of the optical polarizability between light that oscillates parallel and perpendicular to the geometrical axis of the SPR, which can be exploited for DOCT. The need for polarization anisotropy in methods like DOCT, discussed below, also suggests the use of anisotropic particles such as gold nanorods.

There are several notable GNP geometries missing from Fig. 2, including gold nanoshells [41] and nanocages [47], which will be discussed in greater detail in Section VI.

A. Spectroscopic contrast

Spectroscopic OCT (SOCT) was originally developed to assess intrinsic optical properties through analysis of the backscattered OCT spectrum [48]. When GNPs are added to tissue, they modify the native wavelength-dependent scattering and absorption coefficients (μa(λ) and μs(λ), respectively). The resulting OCT signal amplitude is proportional to μs(λ) (presumed to scale with the backscattering coefficient, μb) and decays exponentially in depth, z, proportional to the total extinction μt = μs + μa [49]. Thus, in SOCT, relative μs can be obtained from the overall OCT signal amplitude, and μa is subsequently inferred from a differential with respect to z.

Because tissue is highly scattering in the NIR (μa<<μs) [50], most applications of GNPs with SOCT have employed absorbing GNPs. If we consider the resulting absorption and scattering coefficients in terms of the presence of tissue light scattering structures and absorbing GNPs with densities of ρs and ρa, respectively, we can write:

| (3) |

where εs and εa are the molar extinction coefficients of the tissue and GNPs, respectively. Thus, characterization of εs and εa in advance of an imaging experiment can allow for estimation of the density of absorbing GNPs, ρa, quantitatively. A least-squares solution for this problem exists [51], and models accounting for various noise contributions have been described [52]. There are, of course, many other computational methods for detecting wavelength-dependent absorbers within tissues, including simpler centroid-shifting methods [53], and spectral triangulation [54]. The choice of method should balance the need for accuracy and presence of particular sources of noise (such as modulation of wavelength-dependent scatting in the native tissue) against imaging speed.

Building upon this basic concept, more advanced methods for SOCT-based GNP contrast have been developed. For example, differential contrast between OCT images from a non-overlapping dual-band spectrum has been applied for discrimination between GNPs with different SPR wavelengths [55]. In a similar vein, GNPs synthesized with varying SPR wavelengths have been suggested for contrast imaging of multiple targeting moieties simultaneously [56]. Interestingly, while not demonstrated with SOCT, it may be possible to exploit the SPR red-shift that occurs between GNPs as they are brought into close proximity, which allows one to sense an activatable event such as binding of multiple GNPs to a single location on a cell surface [57].

B. Photothermal contrast

When absorbing GNPs are used with an SPR in the wavelength band of the OCT light, it is often difficult to avoid photothermal heating. Fortunately, the photothermal effect itself can be exploited for contrast. As heat dissipates from the GNP into the surrounding aqueous tissue, two effects occur simultaneously: the refractive index (n0) decreases with temperature T according to dn/dT (which is on the order of −10−4/°C for water), while the volume increases according to the volume expansion coefficient, β (which is on the order of 2−4×10−4/°C for water). These terms respectively decrease and increase the optical path length, with the net path length change being given by the following [58]:

| (4) |

While these effects this may appear to be small, the cumulative effect of over even L0=10μm of path length and a temperature rise of 1°C can give rise to an optical path length difference on the order of 3nm, which is within reach of many phase-sensitive OCT systems.

Like MMOCT, PTOCT is a modulated contrast method (dark contrast method), which offers greater SNR than methods requiring prior knowledge or reference images of tissue in the absence of contrast agents [16]. Typically, PTOCT is performed by modulating a heating beam tuned to the GNP SPR but outside the passband of the OCT beam. OCT can then monitor the resulting modulation of Δz and employ lock-in detection. The dynamics of heat dissipation dictate imaging speed in this method; use of a laser intensity that is too high, or modulation without sufficient rest period between heating events results in loss of thermal confinement that can lead to creep of the tissue temperature over several modulation cycles [58]. Because the temporal response occurs over ~1 ms, modulation speeds on the order of 10-100s of Hz are typical [58, 59].

More advanced methods have been employed to enhance the PTOCT. Initially demonstrated using optical coherence microscopy [60], photothermal optical lock-in OCT (poli-OCT) decreases PTOCT acquisition time and eliminates the need for post-processing of images using temporal phase data by inducing a phase modulation in the reference arm of the interferometer. Setting the integration time of the camera to an integer multiple of the frequency shift period results in low-pass filtering of the signal, isolating the signal due to photothermal heating and reducing signals from static scatterers to zero [61]. Poli-OCT increases image acquisition rates to allow for capturing in vivo time-course dynamics (e.g. blood flow and drug delivery).

C. Diffusion contrast

An emerging form of OCT contrast is exploiting the Brownian diffusion of GNPs as a unique, time-dependent signature assessed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) techniques. DLS is a technology traditionally used for particle sizing, where the ability to depth-resolve DLS signatures in OCT was noted early in the development of OCT [62]. Today, DLS-based OCT is most commonly used to quantify aspects of hemodynamics by measuring red blood cell diffusion and flow [63]. For the purposes of contrast imaging, DLS of GNPs provides some unique opportunities for assessing viscous liquid properties [64] and porous properties [65] of tissues. This is because the translational diffusion rate, DT, of spherical particles within a viscous medium can be described by the Stokes-Einstein relation:

| (5) |

Where η is the medium viscosity, a is the particle radius, and kB is the Boltzmann constant. In practice, the diffusion rate can be quantified by computing the temporal autocorrelation, Γ, of the OCT signal:

| (6) |

where q is the scattering vector equal to 2k in the backscattering geometry of OCT. Importantly, because GNPs are plasmon-resonant, they provide orders-of-magnitude larger optical scattering than non-resonant tissue structures of the same size. Because of the strong size-scaling of optical scattering, tissue features that are larger (on the order of λ) will dominate the endogenous OCT signal. According to Eq. 5, these larger features will exhibit smaller DT, and thus the detection of unusually high DT is a unique signature of GNPs within tissue.

The choice of GNPs is therefore dictated by a need for sufficiently large size to provide optical scattering, balanced against the diffusivity of GNPs into the tissue. In practice, gold nanorods of ~20 nm × 60-80 nm have been found to rapidly homogenize throughout model tissue structures, while being sufficiently large for DOCT detection [65]. Interestingly, gold nanorods also provide polarization anisotropy (Fig. 2), which provides the ability to measure both rotational (DR) and translational (DT) diffusion for further tissue discrimination [64].

The applications of GNP-based DOCT are growing. In tissues, non-adherent GNPs can be designed to diffuse through extracellular pores to monitor tissue remodeling processes [65] that may provide new insight into cancer growth. In liquids such as mucus, GNPs can provide relative measures of hydration [65], providing a metric for assessing respiratory diseases like cystic fibrosis. More comprehensive details are provided in Section VI.

IV. Experimental systems overview

Table 1 provides an overview of many (but not all) magnetic- and plasmonic-based OCT contrast systems reported to date, with emphasis on in vivo experiments, novel particle geometries, and novel imaging schemes. Within each imaging modality (and within each subset of GNP shape), particles are sorted by size from small to large. When possible, a particle concentration is given to aid in general comparison between the techniques, although the reader should be cautioned that direct comparison of concentrations is not always possible due to varying applications and experimental details.

Table 1.

Overview of Magnetic and Plasmonic OCT Experiments

| Citation | Type of particle# | Particle coating |

Size (nm)## | Con- centration### |

Type of sample | Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | OCT | Oh, 2008 [64] |

MIO, bead MIO, bead |

Dextran | 5 (core), 40 (OD) | 0.2 mM Fe/kg | ex vivo rabbit tissue | atherosclerosis |

| Oldenburg, 2010 [74] |

Feridex™, cluster Feridex™, cluster |

Dextran | 5 (core)**, 36-100 (OD) | 70 μg/mL | ex vivo porcine artery | thrombosis | ||

| Oldenburg, 2012 [75] |

MIO, bead MIO, bead |

Dextran | 10-20 (core), 20-30 (OD) | 41-43 μg/mL | ex vivo blood clots | thrombosis | ||

| Oh, 2007 [63] |

Feridex™, cluster Feridex™, cluster |

Dextran | 5 (core)**, 36-100 (OD) | 1.5 mM Fe/kg | ex vivo liver, spleen | macrophages | ||

| Oldenburg, 2005 [4] |

Fe3O4, bead Fe3O4, bead |

(none) | 20-30 (core) | NA | in vivo tadpole | optical biopsy | ||

| John, 2010 [79] |

MIO, bead MIO, bead |

Antibody, dextran |

20-30 (core) | NA | in vivo rat tumor | breast cancer | ||

| Oldenburg, 2008 [81] |

Fe3O4, bead Fe3O4, bead |

(none) | 20-30 (core) | 2 nM* | phantom | tumor imaging | ||

MIO, sphere MIO, sphere |

COOH | 20 (core), 22 (OD) | NA | ex vivo rat tumor | ||||

| John, 2012 [82] |

Ferrofluid/dye-filled Ferrofluid/dye-filledprotein sphere |

Peptide | 20-30 (core)**, 2000-5000 (OD) |

1 × 1011/mL | ex vivo rat tumor | cancer | ||

| Kim, 2013 [30] |

Ferrofluid/dye-filled Ferrofluid/dye-filledprotein sphere |

Peptide | 20-30 (core)**, 2000-5000 (OD) |

.001pM | liquid phantom | intravascular | ||

| Wang, 2010 [88] |

MIO, bead MIO, bead |

Streptavidin | 1000 (core) | <4 mg/mL | in vivo mouse eye | anterior eye | ||

| in vitro mouse eye | ||||||||

| Kim, 2014 [83] |

Ferrofluid/dye-filled Ferrofluid/dye-filledprotein sphere |

Peptide | 20-30 (core)**, 2000-5000 (OD) |

4.48 pM | ex vivo porcine artery | atherosclerosis | ||

| Huang, 2015 [25] |

Fe3O4, cluster Fe3O4, cluster |

NA | NA | <150 ppm | cell culture | cancer | ||

| Oldenburg, 2005 [60] |

Fe3O4, powder Fe3O4, powder |

(none) | 1920 (core) | <1.2 mg/mL | cell culture | cell labeling | ||

| OCE | Crecea, 2009 |

Fe3O4, bead Fe3O4, bead |

(none) | 25 (core) | 2.5 mg/mL | phantom | rheology | |

| Crecea, 2013 [70] |

Fe3O4, bead Fe3O4, bead |

(none) | 25 (core) | NA | ex vivo rabbit tissue | microrheology | ||

| Ahmad, 2014 [29] |

Fe3O4, bead Fe3O4, bead |

(none) | 50-100 (core) | 250 mg/mL | phantom | elastography | ||

| <250 mg/mL | ex vivo rat liver | |||||||

| <250 mg/mL | ex vivo chicken muscle | |||||||

| OCM | Crecea, 2014 [71] |

Ferrofluid-filled Ferrofluid-filledprotein sphere |

NA | 900-3500 (OD) | NA | 3D mammary cell culture | cellular mechanics | |

MIO, bead MIO, bead |

PS & dye | 1000-2000 (OD) | ||||||

| ODT | Kim, 2007 |

Feridex™ Feridex™

|

Dextran | 5 (core)**, 36-100 (OD) | 360 μg Fe / mL* | capillary tube | fluid flow | |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles | DOCT | Lee, 2011 |

Gold, ring Gold, ring |

PEG | 179 (OD), 149 (ID), 97(h) | <40 pM | ex vivo mouse liver | drug delivery |

| Chhetri, 2011[57] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

CTAB | 53 (L), 15 (d) | 1320 pM | viscous fluids | viscometry | ||

| Chhetri, 2014[58] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

PEG | 83 (L), 22 (d) | 112 pM* | 3D airway & breast culture | tissue nanotopology | ||

| Oldenburg, 2013[124] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

PEG | 83 (L), 22 (d) | <547 pM | 3D tumor organoids | molecular imaging | ||

| PTOCT | Chi, 2014[119] |

Gold, ring Gold, ring |

NA | 155 (OD), 130 (ID), 50 (h) | <3.32 pM | ex vivo pig liver | molecular imaging | |

| Tucker, 2015[54] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

PEG | 45.2 (L),13.2 (d) | <200 pM | in vivo mouse ear | molecular imaging | ||

| Xiao, 2013[118] |

Gold, smart rose Gold, smart rose |

C5H7NO3 | 10 (d)** | <60 nM | cell culture | cancer | ||

| Paranjape, 2010[117] |

Gold, rose Gold, rose |

dextran | ~30 (d) | 0.531 pM* | phantom | macrophages | ||

| NA | ex vivo aorta | |||||||

| Adler, 2008[51] |

Gold, shell Gold, shell |

NA | 136 (OD), 120 (ID) | <16.6 pM | GNP solution | molecular imaging | ||

| Nahas, 2014[120] |

Gold, shell Gold, shell |

PEG | 150 (OD), 130 (ID) | <4.15 pM | ex vivo mouse skin | phototherapy | ||

| Zhou, 2010[116] |

Gold, shell Gold, shell |

NA | 152 (OD), 120 (ID) | <8.30 pM | ex vivo breast tissue | molecular imaging | ||

| Skala, 2008[52] |

Gold, sphere Gold, sphere |

PEG | 60 (d) | 26 pM* | liquid phantom | molecular imaging | ||

| <39 pM | cell culture | |||||||

| SOCT | Cang, 2005[40] |

Gold, cage Gold, cage |

NA | 35 (L,w,h) | <500 pM | phantom | molecular imaging | |

| Wei, 2009[97] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

CTAB | NA | 2 pM | phantom | molecular imaging | ||

| Oldenburg, 2009[114] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

CTAB | 45 (L), 15 (d) | <10-20 nM | ex vivo breast tissue | breast cancer | ||

| Jia, 2015[98] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

PEG-Tat | 50-59 (L), 10 (d) | <83 pM | cell culture | retina | ||

| Rawashdeh, 2015[115] |

Gold, rod Gold, rod |

CTAB | 75 (L), 20 (d) | <912 nM | ex vivo chicken | blood vessels | ||

magnetic iron oxide (MIO)

indicated by core, outer diameter (OD) inner diameter (ID), length (L), width (w), diameter (d), or height (h)

by mass density (w/v); particle density (v−1), particle molarity (pM-nM), or dose (molarity Fe/w)

minimum concentration needed for detection

particle size within cluster or fluid

V. Magnetomotive OCT Experiments

This section is organized as follows. First, the various types of magnetomotive optical coherence tomography (MMOCT) systems are described, including phase- vs. amplitude-sensitive and sinusoidal vs. pulsed systems. Next, types of magnetic particles that have been reported to be used with MMOCT imaging are discussed. Finally, the breadth of potential clinical applications for MMOCT is addressed. While this review is intended to represent the widest variety of ongoing efforts in this field, for the sake of brevity only a subset of publications are able to be addressed.

A. System Types

MMOCT was first reported by Oldenburg et al in 2004 [66], with follow-up papers in 2005 [67, 68]. These were obtained using a time-domain OCT system where the B-field was modulated for each A-scan; thus, scan times were quite long (1 minute). Because MMOCT operates by both optical and mechanical principles, tissue phantoms were prepared to mimic the optical and mechanical properties of soft tissue by embedding optically-scattering TiO2 particles into a silicone matrix. The addition of varying amounts of MIOs into each phantom allowed for determination of the MMOCT system sensitivity, which was found to be 220 μg/mL, establishing a starting point for further improvements [68]. The first in vivo MMOCT was obtained in African frog tadpoles (Xenopus laevis) under anesthesia. Magnetic particles were consumed by tadpoles via their suction feeders and subsequently observed within their digestive tract [68].

This early work was performed using a time-domain OCT that was not phase-sensitive, and thus contrast was limited to differences in the OCT signal amplitude. To overcome this limitation, a differential-phase OCT system was developed for sensitive displacement measurement [69], which was applied to magnetomotive imaging [70]. Results demonstrated nanoscale resolution of magnetic particle motion within ex vivo tissues, where the particles had accumulated within the in vivo animal models to demonstrate deliverability [70, 71].

The emergence of spectral- or Fourier-domain OCT provided improved imaging times [72, 73] as well as phase-sensitivity due to the avoidance of moving parts [22]. Crecea et al (2007) investigated the spectral-domain amplitude and phase signals from magnetomotion in phantoms, and observed free oscillations induced after application of a step-like B-field [74]. Further work with phase-resolved magnetomotive OCT by Oldenburg et al (2008) demonstrated sensitivity to nanomolar concentrations of magnetic nanoparticles under sinusoidal modulation [29]; achieving nanomolar sensitivity marked an important milestone for cell-receptor targeted imaging applications.

The application of pulsed magnetic fields has also been explored for MMOCT. By pulsing the electromagnet, one can reduce coil heating effects endemic to the higher duty-cycle sinusoidal method [34]. Using this technique, phantoms with magnetically-labeled cells at a relatively large standoff distance of 30 mm from the coil were imaged [34], and labeled cells within 3D constructs have also been contrasted in pulsed MMOCT [75].

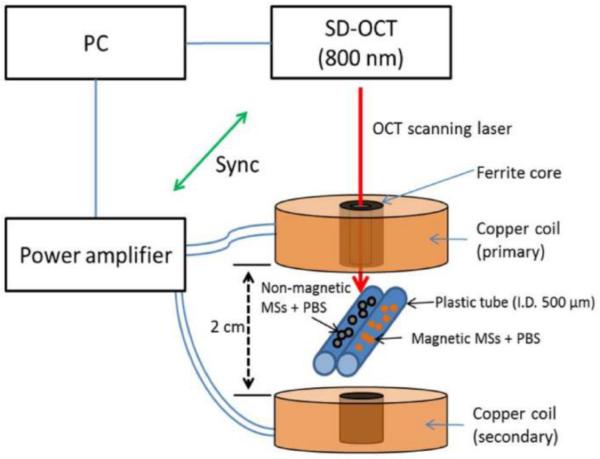

While MMOCT is traditionally used to image elastically-bound MIOs within tissue, the ability to contrast unbound MIOs in free solution, such as the blood volume, would provide new translational opportunities. To address this need, Kim et al (2013) developed the dual-coil MMOCT system displayed in Fig. 3 [33]. In this configuration, the coils are used to apply opposing forces in sequence, in order to initially displace then restore MIOs in solution. Thus, it avoids the need for an intrinsic elastic restoring force to generate a modulated displacement signal.

Fig. 3.

he schematic and output of a dual-coil magnetomotive OCT setup employing magnetically labeled microspheres (MSs) in a flow phantom containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). (Reprinted with permission from [33]).

Magnetomotive optical coherence elastography (MMOCE) is a natural extension of MMOCT that exploits the dependence of induced tissue vibration on its intrinsic mechanical properties. While the vibrational response of tissues to external loading forces was demonstrated via OCE [76], the ability to use MIOs to apply those forces internally in tissues offers added flexibility and with lower strain rates to avoid nonlinearities. In 2013, Crecea et al demonstrated MMOCE by studying free oscillations of ex vivo tissues in response to stepped forces, where the vibrational frequency and rise time were proportionally and inversely related to the elasticity, respectively [77]. Then, in 2014, Crecea et al adapted these methods on an optical coherence microscopy (OCM) setup to investigate biomechanical properties on the single-cell scale [78]. Other efforts in MMOCE have investigated shear-wave methods commonly used in OCE [79].

The frequency-dependence of tissue mechanical properties can also be exploited by interrogating MIOs in tissues at varying frequencies. In 2015, Ahmad et al demonstrate this principle in phantoms and tissues, with validation against finite-element modeling [80]. As an extension of this, Oldenburg et al (2010) developed a resonant acoustic spectroscopy method to measure elasticity of small biosamples with high precision [81]. Interestingly, this has found particular application in the assessment of blood clot elasticity [82, 83], which may in future work connect with the same group’s efforts in magnetically-loaded platelet labeling of blood clots [30].

B. MIO Particle Sizes and Types

Here we will cover the general classes of MIOs used in MMOCT; for more detailed information, the reader is directed to a review on this topic [84]. The choice of magnetic iron oxide particle core size and coating for MMOCT should take into consideration the desired magnetic properties and targeting moieties. For nanoparticles (<100 nm), several general classes of MIOs have been used. One of the most common are dextran-coated MIOs produced by a precipitation method that can be performed without special equipment [85]. These tend to produce particles in the 10-20 nm size range, while the dextran coating can increase their hydrodynamic diameter to 30 nm or more, and have successfully been used in several MMOCT studies [82, 86]. An important class of dextran-coated MIOs are MRI contrast agents FDA-approved as liver contrast agents; of these, Feridex IV™ has been used in several MMOCT studies [30, 70], noting that they are comprised of clusters of ~5 nm MIO cores embedded in a larger dextran matrix, with an overall average hydrodynamic diameter of 36 nm [23].

To generate nanosized MIOs that have greater size monodispersity, synthesis via thermolysis of iron precursors [87]. Commercially available particles prepared in this way are available with a variety of coatings (Ocean Nanotech, Inc.); for MMOCT, COOH-coated MIOs have been employed with success [81, 88].

The conjugation of antibodies onto MIOs confers them with specificity for specific over-expressed cell receptors. John et al (2010) conjugated anti-HER2 onto dextran-coated MIO particles, demonstrating specific uptake into tumors via MMOCT in an in vivo rodent model of breast cancer; the same particles provided MRI contrast for validation of the particle localization within tumors [86].

At the same time, conjugation of fluorescent dyes confers multi-functional (OCT-fluorescence) imaging capabilities that can aid in validating the biodistribution of MIOs used in animal models in vivo. In particular, oil-filled albumin microspheres offer a platform particularly amenable to multi-functionalization. Several studies have demonstrated a class of such microspheres that are filled with an oil-based ferrofluid containing fluorescent dye, while being surface labeled with a peptide to target sites of cancer and atherosclerosis [89, 90]. Because these protein microspheres are nominally 2-5 μm in size, they are appropriate for vascular targets such as atherosclerosis, as well as cancers exhibiting “leaky vasculature” where blood pool agents will tend to accumulate [91]. In addition to these customized multifunctional particles, MMOCT has also been used with commercially available magnetic microbeads that offer fluorescent as well as surface conjugation capabilities [78].

C. Contrast Imaging Applications

While MMOCT is currently a pre-clinical technology, the breadth of research studies implicates a wide variety of future clinical applications. One class of applications lies in tracking magnetically-labeled cells, the feasibility of which was initially demonstrated in 3D cell culture in early MMOCT work [67]. Because macrophages readily phagocytose nanoparticles, MMOCT can be used to track the fate of macrophages in the liver and spleen [70], or macrophage-laden sites of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques [71]. Also, the ability to track stem cells is highly sought after for monitoring stem cell therapies; recently, Cimalla et al. (2015) demonstrated MMOCT of labeled stem cells in vitro [75], working toward a method for monitoring retinal regeneration.

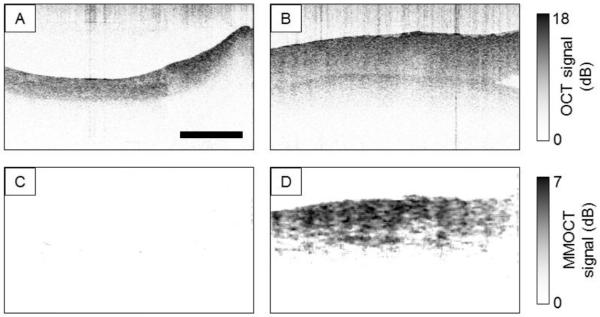

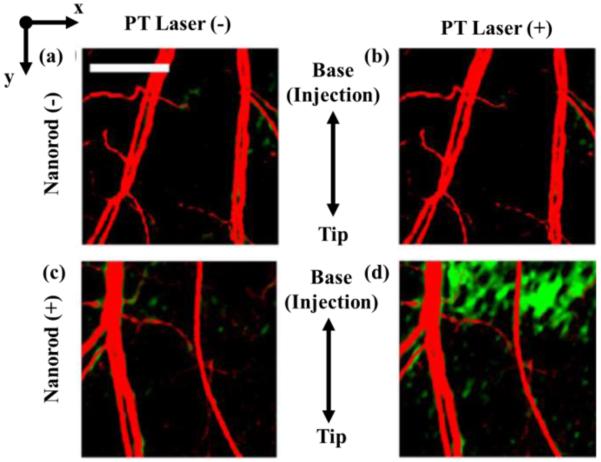

Blood platelets are a powerful tool for functional imaging, as they readily take up foreign particles via a mechanisms known as “covercytosis” [92], and play a crucial role in hemostasis and thrombosis [93]. Thus, the highly functional nature of platelets can be used to target sites of vascular damage where blood clots form. As shown in Fig. 4, MMOCT of magnetically-labeled platelets flowed through ex vivo porcine arteries exhibits highly specific contrast only to damaged blood vessel walls [30]. In combination with existing technologies for cardiovascular imaging [4], MMOCT of labeled platelets, macrophages, or functionalized microspheres discussed in the previous subsection, may play a role in identifying sites of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque.

Fig. 4.

Sample B-mode images of ex vivo porcine arteries following exposure in a flow chamber to SPIO-RL platelets. (a) OCT image of control artery (b) OCT image of damaged artery (c) magnetomotive OCT image of control artery (d) magnetomotive OCT image of damaged artery. Note that each artery is longitudinally cut with the luminal wall facing upward. Scale bar: 0.5 mm (Reprinted with permission from [30]).

Moving beyond pure imaging applications, there has been recent development in the area of theranostics (i.e., simultaneous diagnostics and treatment). Huang et al. (2015) report a novel clustered magnetic nanoparticle with both light scattering properties at 860 nm for OCT imaging, and absorbing properties at 1064 nm for photothermal therapy [27]. Thus, cancer cells were shown to be both imaged and subjected to hyperthermia by the same particles. Interestingly, the potential exists to provide heating to tissue directly via magnetic fluid hyperthermia by applying a magnetic field modulated in the 100’s of kHz [94], a technique that has yet to be explored in conjunction with MMOCT.

Given the widespread use of OCT in ophthalmic applications, it should be noted that MMOCT has also been explored in this area. In 2010, Wang et al. reported the ability to contrast magnetic beads in the anterior segment of a mouse eye, which was overlaid on the structural OCT image [95]. The same group subsequently developed a SOCT-MMOCT platform for detecting cochlin (a precursor of glaucoma) in the trabecular meshowork of mice using anti-cochlin labeled magnetic particles [96].

Elastographic applications of magnetomotive imaging via MMOCE are also under development. For example, measurements of lung epithelium compliance can aid in tracking the progression of bronchiectasis in diseases such as COPD; Chhetri et al. (2010) demonstrated MMOCE measurements of in vitro human tracheo-bronchial-epithelial (hBE) cells [97]. More recent technological developments by Ahmad et al. (2014) have demonstrated promising capabilities for shear-wave based MMOCE in tissues ex vivo [79].

All of these potential applications will be aided by the continually improving acquisition rates in OCT technology, which have recently been shown to enable acquisition of entire OCT volumes during modulation of the magnetic field for volumetric MMOCT [32].

VI. Plasmonic Nanoparticle OCT Experiments

Nanoparticles have recently gained popularity for medical imaging and therapeutics due to their size and unique optical properties. The size and shape of these nanoparticles govern their optical response with the wavelength at plasmon resonance (λSPR) typically occurring in the near-infrared (NIR) “biological imaging window.” By altering the size and shape of these plasmonic gold nanoparticles (GNPs), λSPR can be shifted to wavelengths from red into the NIR, within the detection range of typical OCT systems, making them attractive candidates as contrast agents in tissue using current OCT imaging techniques.

The GNPs reviewed here are primarily gold taking the shape of rods, roses, spheres, shells, cages, and stars/branches. These shapes offer their own unique optical properties and biological characteristics to be discussed. Nanospheres offer a plasmon resonance mode with dependence on diameter [98]; cylindrically-shaped nanorods offer two plasmon resonant modes (longitudinal and transverse) that can be tuned to the near-IR by adjusting the aspect ratio of their length (L) to diameter (d), [99], as described in Section III. Nanoroses are a conglomeration of smaller nanospheres (~10nm), that alone, are too small to exhibit a plamon resonance, but do as a whole [100]. Nanostars are created from spherical gold seeds and have gold branches stemming from the center. The plasmon resonance of these structures is governed by the length of these branches and the size of the initial seed, that acts to enhance plasmon resonance at the tips [101]. Gold nanocages, created from silver nanostructures through a galvanic replacement process, are gold frames taking various geometric shapes (e.g. cubes and polyhedrons). The λSPR of these structures, tunable to the NIR at exceptionally small sizes, are governed by the outer width (w) and frame thickness (t), with absorption dominating for structures <45nm [39]. Nanoshells, created by growing gold on a dielectric core, can be tuned with higher precision than other GNPs by altering the fabrication materials and size (outer diameter, OD, and inner diameter, ID), [41]. Finally, nanorings exhibit a plasmon resonance dependent upon the ratio of the outer diameter to the ring thickness. Nanorings can exhibit redshifts into the NIR as large as 100’s of nm by making small changes to the ring thickness, while keeping the overall outer diameter constant [40].

The properties of these GNPs offer unique contributions that lend to a wide variety of biomedical imaging, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications. Below, we review this variety of applications using spectroscopic, photothermal, and diffusion OCT (SOCT, PTOCT, and DOCT).

A. Spectroscopic systems

In SOCT, localized spectral measurements are taken within the OCT image. However, the strongly modulated spectrum of tissue light scattering, and the fundamental trade-off between spatial and spectral resolution makes SOCT challenging for biomedical applications. Several techniques have been described to overcome these challenges, including differential absorption [102], spectral fractionation [103], and spectral triangulation [104]. These methods require scatterers with known spectral characteristics that can be tuned with respect to the OCT signal bandwidth (ΔλOCT), for which GNPs are well suited. Before discussing the application of GNPs for spectroscopic (wavelength-dependent) contrast, it is prudent to first mention work done to enhance intensity-based contrast (i.e., changes to the overall OCT signal intensity) through exploitation of GNP’s unique absorption and scattering characteristics.

Because GNPs strongly absorb/scatter light at tunable wavelengths, OCT intensity imaging can be enhanced for better contrast and penetration in tissue. Oldenburg et al. first described gold nanorods as contrast agents in OCT using their low backscattering albedo compared to that of tissue [44]. Around the same time, Chen et al. investigated small nanocages (<40 nm) as absorptive contrast agents in OCT, with implications for cell targeting in both diagnostics and therapeutics. These studies paved the way for contrast enhancement using highly absorbing/scattering GNPs. For example, nanoshells have been used in imaging and ablating tumors in mice [105] and contrasting in vivo on pig skin [106] and rabbit skin [107]; nanorods have been used to enhance contrast in tumors [108] and in vivo mouse eyes [109]; nanostars have been used in cell imaging [110]; and nanoparticle accumulation in tumors has been monitored [111].

Building upon these works, investigators have derived new methods and applications of OCT intensity contrast. For example, Tseng et al. showed that strong absorption by gold nanorings at λOCT could heat pig adipose during imaging, changing the tissue properties and thereby enhancing contrast [112]. Xi et al. introduced a new method of characterizing nanoparticle properties by cross-referencing with tissue void of nanoparticles [113]. Doppler OCT has been enhanced using gold nanorods by Wang et al. for imaging ocular flow [114]. Sirotkina et al. found that OCT intensity enhancement could be used to estimate gold nanoparticle accumulation in tumors for guided laser hyperthermia [115]. Later, Couglin et al. showed that by conjugating gold nanoshells with Gadolinium, contrast could be enhanced for MRI and X-Ray, in addition to OCT, for multimodal diagnostics and therapeutics in cancer [116]. Lastly, the growth of nanocubes has been studied by Ponce de Leon et al., by monitoring enhanced contrast during the nanocube growth [117].

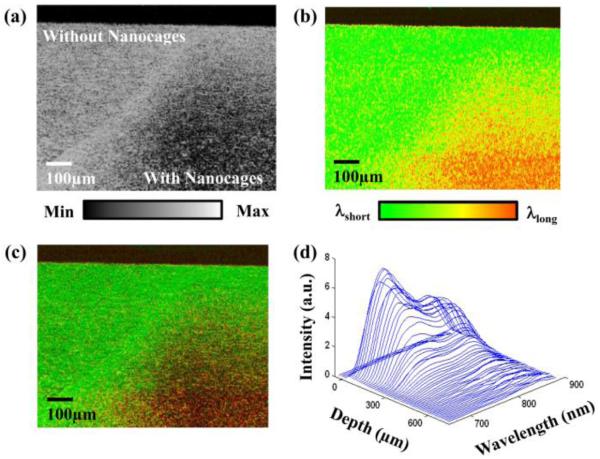

While extensive work has been done studying intensity contrast enhancements using GNPs, few have exploited their wavelength-dependent properties to provide more specific contrast against the tissue background. Cang et al. introduced gold nanocages as contrast agents in spectroscopic OCT [47]. The strong absorption at λSPR for the 35 nm cages allowed for stronger contrast within ΔλOCT, providing contrast via both the spectral content and change in overall OCT intensity (shown in Fig. 5). Oldenburg et al. extended this technique, first into interlipid phantoms [118], and then into ex vivo tissue using gold nanorods [119]. The authors showed that relative nanorod density was evident against strong scattering in human carcinoma breast tissue, lending toward an in vivo human tumor contrast agent.

Fig. 5.

Spectroscopic OCT images of TiO2 gelatin phantom, with right side doped with 35 nm nanocages. (a) Standard OCT showing decreasing signal in location with absorbing nanocages. (b) Spectroscopic OCT showing changes in scattered spectra. (c) Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) image of the same cross section with hue representing centroid wavelength, and saturation/value representing OCT intensity. (d) Plot of intensity versus depth versus wavelength. (Reprinted with permission from [47]).

Other methods of spectroscopic OCT have recently been employed. Wei et al. demonstrated the use of GNRs with different aspect ratios, thus different λSPR, as a method of differential absorption OCT, with implications in molecular imaging and contrasting highly scattering tissues [102]. Expanding on differential absorption contrast techniques, Rawashdeh et al. showed that a dual-bandwidth OCT system was capable of providing spectroscopic contrast using different sizes of nanorods tuned to different λSPR [43]. This technique was demonstrated in agar/TiO2 phantoms and ex vivo muscle tissue. Similarly, Jia et al. employ a new method of spectral fractionalization by dividing the OCT bandwidth into sub-bands, providing OCT contrast by comparing the ratio of short to long wavelengths [103]. They demonstrate this method in an interlipid tissue phantom and in vitro using a 3D cell culture, moving toward imaging the human retina in vivo.

B. Photothermal

PTOCT provides enhanced tissue contrast by exploiting the photothermal properties of GNPs heated at λSPR. This method is especially attractive for cancer applications due to its ability to both detect GNPs in tissue and induce a therapeutic response by tissue through GNP heating. The following describes work that has been done using GNP contrast enhancement with PTOCT.

This was first demonstrated nearly simultaneously by two research groups. Adler et al. introduced 120 nm gold nanoshells for contrast enhancement using photothermal OCT, demonstrated in tissue phantoms [58]. Skala et al. applied PTOCT in 2D and 3D cell cultures using 60 nm gold nanospheres [59]. Zhou et al. demonstrated the use of nanoshells in ex vivo breast tissue, and showed that oversampling improves SNR [120]. More complex nanoparticle constructs were introduced by Paranjape et al., who used gold nanoroses to detect macrophages [121]. Small nanospheres were clustered together, forming roses, to exhibit strong absorption at the tuned λSPR, making them attractive candidates for photothermal OCT. The tunability of these clusters post-manufacturing gives them the unique ability to sense different types of environments. These “smart” particles can be engineered to cluster under specific conditions, such that λSPR shifts into the photothermal imaging window at discrete clustering states. Xiao et al. demonstrated this using pH-activated aggregation for cell imaging [122]. Chi et al. took advantage of the ability for nanorings to be tuned far into the infrared by using two OCT systems, one with λOCT matching λSPR, and the other with λOCT outside the peak of λSPR [123]. The authors found that PTOCT could disambiguate the source of scattering seen in conventional OCT images. Furthermore, they found that when using PTOCT with λOCT= λSPR, only tissue scattering was seen with OCT, with nanorings being detected with PTOCT.

Recently, new techniques have been employed to enhance PTOCT abilities using GNPs. Nahas, et al. combined full-field OCT (FFOCT), which collects high resolution (~1 μm) en face 2D images, with PTOCT techniques using nanospheres [124]. Because FFOCT only images the surface of the tissue, thermal responses of the tissue to modulated energy pulses were delayed with rates dependent upon particle depth. The authors were able to extract the depth location of nanospheres in tissue based on these response delay times to triangulate the location of nanospheres in 3D tissue. This technique allows the combined benefit of high resolution FFOCT and cell targeting with PTOCT. In addition to resolution enhancement, speed of PTOCT has been improved using optical lock-in techniques (coined poli-OCT), previously described by Pache et al. for optical coherence microscopy [60]. Tucker-Schwartz et al. employed these methods to improve imaging speed in an in vivo mouse ear [61]. Here, they show that poli-OCT can disambiguate motion due to blood flow against the PTOCT signal (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Matrigel containing gold nanorods injected into an in vivo mouse ear showing blood flow via speckle variance (red) and nanorods via PTOCT (green). (a) Blood flow without nanorods and with modulating laser off. (b) Blood flow without nanorods and with modulating laser on. (c) Blood flow with nanorods and the modulating laser off. (d) Blood flow with nanorods and the modulating laser on. (Reprinted with permission from [61]).

C. Diffusion

As technology progresses with OCT, new methods are possible owing to increased imaging rates and resolution. Particles exhibit a natural Brownian motion that can be measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) within a coherence volume [62]. The rapid collection rates and coherence gating techniques used in spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) makes it an attractive candidate for measuring these movements using DLS, as has previously been shown [125]. Furthermore, SD-OCT with polarization sensitivity (PS-OCT) allows for discrimination between optically anisotropic scatterers (like nanorods) and isotropic particles (like cells). The small size and strong scattering of GNPs make them excellent candidates for diffusion OCT (DOCT).

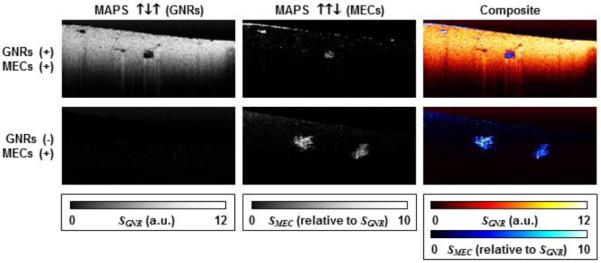

Diffusion of gold nanorings was first tracked by Lee, et al. The authors were able to contrast diffusion of these nanorings against native tissue by mapping OCT speckle variance within the image to track the diffusion of these particles over time [126]. Exploiting the optical anisotropy of nanorods, Mehta and Chen used simulations to show enhanced polarization sensitive contrast using a chiral nanostructure constructed from two nanorods [127]. Chhetri et al. used this polarization sensitivity to monitor rotational motion of rods, whose movement about the axis results in polarization dependent intensity fluctuations. Using DLS theory, the authors showed the rotational diffusion of gold nanorods could accurately predict the viscosity of a Newtonian diffusion in liquids [64]. Oldenburg et al. then used DOCT to discriminate between tissue and cells using the decorrelation time of speckle fluctuations (A) in addition to the cross-polarized intensity signals (PS) that are only evident from nanorod scatters [42]. The authors found that these properties, along with cellular motility measurements (M), created unique MAPS signatures by which cells and tissue could be clearly contrasted, with applications ranging from functional drug delivery to quantification of tissue properties. Fig. 7 shows an example of this MAPS (motility-amplitude-polarization-sensitive) signature in artificial tissue seeded with mammary epithelial cells. This group later extended DOCT measurements to quantify non-Newtonian fluids (polyethylene glycol) which led to quantification of polymeric tissues like mucus and artificial tissue. Chhetri et al. showed that nanorod diffusion could predict the diseased state of mucus, with implications in treating respiratory diseases like Cystic Fibrosis, and the extracellular matrix, with implications for monitoring the diseased state of tissue during tumorigenesis [65].

Fig. 7.

MAPS signature in a cell culture containing mammary epithelial cells where DOCT was used to enhance contrast of tissue containing gold nanorods against cells void of nanorods. (Reprinted with permission from [42]).

VII. Conclusion

The use of magnetic iron oxide and plasmonic gold nanoparticles offer many advantages for OCT contrast, in addition to excellent biocompatibility. The choice of a particular particle and contrast method should be considered relative to the needed application, ranging from molecular contrast imaging of cell surface receptors, to the quantification of extracellular nanoporosity. All of the above methods offer sufficiently high imaging speeds and safety to be used in vivo, which may lead to new clinical applications for diagnostics, guidance, and treatment monitoring.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (CBET 1351474), and the National Institutes of Health, (R21 HL 119928 and R21 HL 111968).

Biography

Amy L. Oldenburg received the B.S. degree in applied physics from the California Institute of Technology in 1995 and the Ph.D. degree in physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2001.

From 2001 to 2008, she was a postdoctoral research associate and subsequently senior research scientist at the Beckman Institute at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where she invented magnetomotive OCT, and investigated a variety of OCT contrast agents for biomedical applications including breast cancer molecular imaging and elastography. Since 2008, she has been directing the Coherence Imaging Laboratory in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, as an assistant and subsequently associate professor.

Dr. Oldenburg was a recipient of the NSF CAREER award in 2014. Dr. Oldenburg became a Senior Member of OSA in 2013, and a Senior Member of SPIE in 2011.

Richard L. Blackmon received a B.S. degree in electrical engineering in 2009 and a Ph.D. degree in optical science and engineering in 2013, both from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

From 2008-2013, he was a research assistant in the Biomedical Optics Laboratory in the Department of Physics and Optical Science, where he investigated laser therapeutics in urology. Since 2013, he has been a postdoctoral research associate in the in the Coherence Imaging Laboratory in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where he investigates OCT imaging of diffusing gold nanoparticles for elastography of diseased tissue.

Dr. Blackmon was a recipient of the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship in 2010 and the UNC Charlotte Graduate Life Fellowship in 2013. He is a current OSA and SPIE member.

Justin M. Sierchio received BS, MS, and PhD degrees in optical sciences and engineering from the College of Optical Sciences at the University of Arizona in 2006, 2008, and 2014, respectively. He also served as a principle research specialist at the University of Arizona, working on designs of diabetic foot wound recovery sensors and point-of-care (POC) monitoring devices. Since 2015, he has been a postdoctoral research associate at the Optical Coherence Imaging Laboratory in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, investigating development of magnetomotive ultrasound (MMUS) techniques for thrombosis and atherosclerosis characterization. He is a member of SPIE.

Footnotes

Additional information can be found at http://user.physics.unc.edu/~aold/.

Contributor Information

Amy L. Oldenburg, Email: aold@physics.unc.edu, Department of Physics and Astronomy, the Department of Biomedical Engineering, and the Biomedical Research Imaging Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3255 USA.

Richard L. Blackmon, Email: rlblackm@email.unc.edu, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3255 USA.

Justin M. Sierchio, Email: jmsierch@email.unc.edu, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3255 USA.

REFERENCES

- [1].Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, Hee MR, Flotte T, Gregory K, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991 Nov 22;254:1178–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Swanson EA, Izatt JA, Hee MR, Huang D, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. In vivo retinal imaging by optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 1993;18:1864–1866. doi: 10.1364/ol.18.001864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Izatt JA, Hee MR, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Huang D, Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. Micrometer-scale resolution imaging of the anterior eye in vivo with optical coherence tomography. Archives of ophthalmology. 1994;112:1584–1589. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090240090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jang I-K, Bouma BE, Kang D-H, Park S-J, Park S-W, Seung K-B, Choi K-B, Shishkov M, Schlendorf K, Pomerantsev E. Visualization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in patients using optical coherence tomography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:604–609. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01799-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boppart SA, Luo W, Marks DL, Singletary KW. Optical coherence tomography: feasibility for basic research and image-guided surgery of breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2004 Mar;84:85–97. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000018401.13609.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, Compton CC, Nishioka NS. High-resolution imaging of the human esophagus and stomach in vivo using optical coherence tomography. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2000;51:467–474. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sivak MV, Kobayashi K, Izatt JA, Rollins AM, Ung-Runyawee R, Chak A, Wong RC, Isenberg GA, Willis J. High-resolution endoscopic imaging of the GI tract using optical coherence tomography. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2000;51:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Armstrong J, Leigh M, Walton I, Zvyagin A, Alexandrov S, Schwer S, Sampson D, Hillman D, Eastwood P. In vivo size and shape measurement of the human upper airway using endoscopic longrange optical coherence tomography. Optics express. 2003 Jul 28;11:1817–26. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.001817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fercher AF, Drexler W, Hitzenberger CK, Lasser T. Optical coherence tomography-principles and applications. Reports on Progress in Physics. 2003;66:239. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schmitt JM, Kumar G. Optical scattering properties of soft tissue: a discrete particle model. Applied optics. 1998;37:2788–2797. doi: 10.1364/ao.37.002788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Drexler W, Fujimoto JG. State-of-the-art retinal optical coherence tomography. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2008;27:45–88. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jang I-K, Tearney GJ, MacNeill B, Takano M, Moselewski F, Iftima N, Shishkov M, Houser S, Aretz HT, Halpern EF. In vivo characterization of coronary atherosclerotic plaque by use of optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2005;111:1551–1555. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159354.43778.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang RK, An L, Francis P, Wilson DJ. Depth-resolved imaging of capillary networks in retina and choroid using ultrahigh sensitive optical microangiography. Optics letters. 2010;35:1467–1469. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.001467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zysk AM, Boppart SA. Computational methods for analysis of human breast tumor tissue in optical coherence tomography images. Journal of biomedical optics. 2006 Sep-Oct;11:054015. doi: 10.1117/1.2358964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee TM, Oldenburg AL, Sitafalwalla S, Marks DL, Luo W, Toublan FJ-J, Suslick KS, Boppart SA. Engineered microsphere contrast agents for optical coherence tomography. Optics letters. 2003;28:1546–1548. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang C. Molecular Contrast Optical Coherence Tomography: A Review¶. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2005;81:215–237. doi: 10.1562/2004-08-06-IR-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Prabhakar U, Maeda H, Jain RK, Sevick-Muraca EM, Zamboni W, Farokhzad OC, Barry ST, Gabizon A, Grodzinski P, Blakey DC. Challenges and Key Considerations of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect for Nanomedicine Drug Delivery in Oncology. Cancer research. 2013 Apr 15;73:2412–2417. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4561. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cai W, Chen X. Nanoplatforms for Targeted Molecular Imaging in Living Subjects. Small. 2007;3:1840–1854. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Oldenburg AL, Applegate BE, Izatt JA, Boppart SA. Molecular OCT Contrast Enhancement and Imaging. In: Drexler W, Fujimoto JG, editors. Optical Coherence Tomography: Technology and Applications. 1 ed Springer; pp. 713–756. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Boppart SA, Oldenburg AL, Xu C, Marks DL. Optical probes and techniques for molecular contrast enhancement in coherence imaging. Journal of biomedical optics. 2005 Jul-Aug;10:41208. doi: 10.1117/1.2008974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schenck JF. The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Medical physics. 1996;23:815–850. doi: 10.1118/1.597854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Choma MA, Ellerbee AK, Yang C, Izatt JA. Spectral domain phase microscopy. Biomedical Topical Meeting.2004. p. SC5. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Clement O, Siauve N, Cuénod C-A, Frija G. Liver Imaging With Ferumoxides (Feridex (R)): Fundamentals, Controversies, and Practical Aspects. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1998;9:167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Woo K, Hong J, Choi S, Lee H-W, Ahn J-P, Kim CS, Lee SW. Easy synthesis and magnetic properties of iron oxide nanoparticles. Chemistry of Materials. 2004;16:2814–2818. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tang J, Myers M, Bosnick KA, Brus LE. Magnetite Fe3O4 nanocrystals: spectroscopic observation of aqueous oxidation kinetics. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2003;107:7501–7506. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sosnovik DE, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R. Magnetic nanoparticles for MR imaging: agents, techniques and cardiovascular applications. Basic research in cardiology. 2008;103:122–130. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0710-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Huang C-C, Chang P-Y, Liu C-L, Xu J-P, Wu S-P, Kuo W-C. New insight on optical and magnetic Fe3O4 nanoclusters promising for near infrared theranostic applications. Nanoscale. 2015;7:12689–12697. doi: 10.1039/c5nr03157e. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nguyen FT, Dibbern EM, Chaney EJ, Oldenburg AL, Suslick KS, Boppart SA. Magnetic protein microspheres as dynamic contrast agents for magnetomotive optical coherence tomography. In: Achilefu S, Bornhop DJ, Raghavachari R, editors. Molecular Probes for Biomedical Applications Ii. Vol. 6867 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Oldenburg AL, Crecea V, Rinne SA, Boppart SA. Phase-resolved magnetomotive OCT for imaging nanomolar concentrations of magnetic nanoparticles in tissues. Optics express. 2008 Jul 21;16:11525–11539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Oldenburg AL, Gallippi CM, Tsui F, Nichols TC, Beicker KN, Chhetri RK, Spivak D, Richardson A, Fischer TH. Magnetic and Contrast Properties of Labeled Platelets for Magnetomotive Optical Coherence Tomography. Biophysical journal. 2010 Oct 6;99:2374–2383. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fortin J-P, Wilhelm C, Servais J, Ménager C, Bacri J-C, Gazeau F. Size-Sorted Anionic Iron Oxide Nanomagnets as Colloidal Mediators for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007 Mar 01;129:2628–2635. doi: 10.1021/ja067457e. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ahmad A, Kim J, Shemonski ND, Marjanovic M, Boppart SA. Volumetric full-range magnetomotive optical coherence tomography. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2014 Dec;19 doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.12.126001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim J, Ahmad A, Boppart SA. Dual-coil magnetomotive optical coherence tomography for contrast enhancement in liquids. Optics Express. 2013 Mar 25;21:7139–7147. doi: 10.1364/OE.21.007139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Koo J, Lee C, Kang HW, Lee YW, Kim J, Oh J. Pulsed magneto-motive optical coherence tomography for remote cellular imaging. Optics Letters. 2012;37:3714–3716. doi: 10.1364/OL.37.003714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Higby GJ. Gold in medicine. Gold bulletin. 1982;15:130–140. doi: 10.1007/BF03214618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schaeublin NM, Braydich-Stolle LK, Schrand AM, Miller JM, Hutchison J, Schlager JJ, Hussain SM. Surface charge of gold nanoparticles mediates mechanism of toxicity. Nanoscale. 2011;3:410–420. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00478b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yguerabide J, Yguerabide EE. Light-scattering submicroscopic particles as highly fluorescent analogs and their use as tracer labels in clinical and biological applications: I. Theory. Analytical biochemistry. 1998;262:137–156. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:2115–2120. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Skrabalak SE, Chen J, Sun Y, Lu X, Au L, Cobley CM, Xia Y. Gold Nanocages: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2008 Dec;41:1587–1595. doi: 10.1021/ar800018v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Aizpurua J, Hanarp P, Sutherland DS, Käll M, Bryant GW, García de Abajo FJ. Optical Properties of Gold Nanorings. Physical Review Letters. 2003;90 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.057401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Loo C, Lin A, Hirsch L, Lee MH, Barton J, Halas NJ, West J, Drezek R. Nanoshell-enabled photonics-based imaging and therapy of cancer. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 2004 Feb;3:33–40. doi: 10.1177/153303460400300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Oldenburg AL, Chhetri RK, Cooper JM, Wu WC, Troester MA, Tracy JB. Motility-, autocorrelation-, and polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography discriminates cells and gold nanorods within 3D tissue cultures. Opt Lett. 2013 Aug 1;38:2923–6. doi: 10.1364/OL.38.002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Al Rawashdeh W. e., Weyand T, Kray S, Lenz M, Buchkremer A, Spöler F, Simon U, Möller M, Kiessling F, Lederle W. Differential contrast of gold nanorods in dual-band OCT using spectral multiplexing. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2015;17 [Google Scholar]

- [44].Oldenburg AL, Hansen MN, Zweifel DA, Wei A, Boppart SA. Plasmon-resonant gold nanorods as low backscattering albedo contrast agents for optical coherence tomography. Optics express. 2006 Jul 24;14:6724–6738. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.006724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bohren CF, Huffman DR. Absorption and scattering of light by small particles. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sonnichsen C, Franzl T, Wilk T, von Plessen G, Feldmann J, Wilson O, Mulvaney P. Drastic reduction of plasmon damping in gold nanorods. Physical Review Letters. 2002;88:077402–077402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.077402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cang H, Sun T, Li ZY, Chen JY, Wiley BJ, Xia YN, Li XD. Gold nanocages as contrast agents for spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2005 Nov;30:3048–3050. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.003048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Morgner U, Drexler W, Kärtner F, Li X, Pitris C, Ippen E, Fujimoto J. Spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2000;25:111–113. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Thrane L, Yura HT, Andersen PE. Analysis of optical coherence tomography systems based on the extended Huygens–Fresnel principle. JOSA A. 2000;17:484–490. doi: 10.1364/josaa.17.000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cheong W-F, Prahl SA, Welch AJ. A review of the optical properties of biological tissues. IEEE journal of quantum electronics. 1990;26:2166–2185. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Xu C, Marks D, Do M, Boppart S. Separation of absorption and scattering profiles in spectroscopic optical coherence tomography using a least-squares algorithm. Optics Express. 2004;12:4790–4803. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.004790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Oldenburg AL, Hansen MN, Wei A, Boppart SA. Plasmon-resonant gold nanorods provide spectroscopic OCT contrast in excised human breast tumors. Biomedical Optics (BiOS) 2008. 2008:68670E–68670E-10. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Xu C, Ye J, Marks DL, Boppart SA. Near-infrared dyes as contrast-enhancing agents for spectroscopic optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2004;29:1647–1649. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.001647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yang C, McGuckin LE, Simon JD, Choma MA, Applegate BE, Izatt JA. Spectral triangulation molecular contrast optical coherence tomography with indocyanine green as the contrast agent. Optics Letters. 2004;29:2016–2018. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.002016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Weyand T, Kray S, Lenz M, Buchkremer A, Spöler F, Simon U, Möller M, Kiessling F, Lederle W. Differential contrast of gold nanorods in dual-band OCT using spectral multiplexing. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2015;17:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Oldenburg SJ, Jackson JB, Westcott SL, Halas N. Infrared extinction properties of gold nanoshells. Applied Physics Letters. 1999;75:2897–2899. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sokolov K, Follen M, Aaron J, Pavlova I, Malpica A, Lotan R, Richards-Kortum R. Real-time vital optical imaging of precancer using anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles. Cancer research. 2003;63:1999–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Adler DC, Huang SW, Huber R, Fujimoto JG. Photothermal detection of gold nanoparticles using phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2008 Mar;16:4376–4393. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.004376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Skala MC, Crow MJ, Wax A, Izatt JA. Photothermal Optical Coherence Tomography of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Live Cells Using Immunotargeted Gold Nanospheres. Nano Letters. 2008 Oct 08;8:3461–3467. doi: 10.1021/nl802351p. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Pache C, Bocchio NL, Bouwens A, Villiger M, Berclaz C, Goulley J, Gibson MI, Santschi C, Lasser T. Fast three-dimensional imaging of gold nanoparticles in living cells with photothermal optical lock-in Optical Coherence Microscopy. Optics Express. 2012 Sep 10;20:21385–21399. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.021385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Tucker-Schwartz JM, Lapierre-Landry M, Patil CA, Skala MC. Photothermal optical lock-in optical coherence tomography for in vivo imaging. Biomed Opt Express. 2015 Jun 1;6:2268–82. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.002268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Boas DA, Bizheva KK, Siegel AM. Using dynamic low-coherence interferometry to image Brownian motion within highly scattering media. Optics Letters. 1998 Mar 1;23:319–321. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lee J, Wu W, Jiang JY, Zhu B, Boas DA. Dynamic light scattering optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2012;20:22262–22277. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.022262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Chhetri RK, Kozek KA, Johnston-Peck AC, Tracy JB, Oldenburg AL. Imaging three-dimensional rotational diffusion of plasmon resonant gold nanorods using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Physical Review E. 2011;83 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.040903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chhetri RK, Blackmon RL, Wu WC, Hill DB, Button B, Casbas-Hernandez P, Troester MA, Tracy JB, Oldenburg AL. Probing biological nanotopology via diffusion of weakly constrained plasmonic nanorods with optical coherence tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Oct 14;111:E4289–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409321111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Oldenburg AL, Gunther JR, Toublan FJ, Marks DL, Suslick KS, Boppart SA, Izatt JA, Fujimoto JG. Magnetic contrast agents for optical coherence tomography. 2004;5316:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Oldenburg AL, Gunther JR, Boppart SA. Imaging magnetically labeled cells with magnetomotive optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2005 Apr 1;30:747–749. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.000747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Oldenburg AL, Toublan FJJ, Suslick KS, Wei A, Boppart SA. Magnetomotive contrast for in vivo optical coherence tomography. Optics express. 2005 Aug 22;13:6597–6614. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.006597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Davé DP, Milner TE. Optical low-coherence reflectometer for differential phase measurement. Optics Letters. 2000 Feb 15;25:227–229. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.000227. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Oh J, Feldman MD, Kim J, Kang HW, Sanghi P, Milner TE. Magneto-motive detection of tissue-based macrophages by differential phase optical coherence tomography. Lasers Surg Med. 2007 Mar;39:266–72. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Oh J, Feldman MD, Kim J, Sanghi P, Do D, Mancuso JJ, Kemp N, Cilingiroglu M, Milner TE. Detection of macrophages in atherosclerotic tissue using magnetic nanoparticles and differential phase optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt. 2008 Sep-Oct;13:054006. doi: 10.1117/1.2985762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Choma M, Sarunic M, Yang C, Izatt J. Sensitivity advantage of swept source and Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2003;11:2183–2189. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.002183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Leitgeb R, Hitzenberger C, Fercher A. Performance of fourier domain vs. time domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2003;11:889–894. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]