Abstract

Background Chloroquine is an inexpensive and widely available 9‐aminoquinolone used in the management of malaria. Recently, in vitro assays suggest that chloroquine may have utility in the treatment of several viral infections including influenza.

Objectives We sought to test whether chloroquine is effective against influenza in vivo in relevant animal models.

Methods The effectiveness of chloroquine at preventing or ameliorating influenza following viral challenge was assessed in established mouse and ferret disease models.

Results Although active against influenza viruses in vitro, chloroquine did not prevent the weight loss associated with influenza virus infection in mice after challenge with viruses expressing an H1 or H3 hemagglutinin protein. Similarly, clinical signs and viral replication in the nose of ferrets were not altered by treatment.

Conclusions Although in vitro results were promising, chloroquine was not effective as preventive therapy in vivo in standard mouse and ferret models of influenza virus infection. This dampens enthusiasm for the potential utility of the drug for humans with influenza.

Keywords: Influenza, chloroquine, ferret, antiviral

Despite the availability of effective antiviral drugs, 1 influenza causes 3–5 million severe illnesses and 250 000–500 000 deaths in the industrialized world annually. 2 There are two classes of drugs currently licensed for use against influenza. The adamantanes, amantadine and rimantadine, target the M2 ion channel, and the neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) target the viral sialidase. The adamantane class of drugs has limited effectiveness against currently circulating strains of influenza due to the emergence of resistance. 3 Resistance to the NAIs is not as widespread but is becoming a concern in populations where use is frequent 4 and in the treatment of H5N1 influenza. 5 In addition, NAIs are expensive and are not readily available in many parts of the world. There is therefore intense interest and urgency in the development of new therapeutics that can be implemented for the treatment of influenza.

Recently, a series of in vitro studies have suggested that the antimalarial drug chloroquine may have activity against influenza and other emerging respiratory pathogens. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Chloroquine is a lysosomotropic agent that accumulates in the endosomal compartment where it can impair the acidification of the endosome and prevent the conformational changes associated with viral fusion and release into the cytosol. In addition to the effect seen in the endosomal compartment, the drug can also impair viral replication by inhibiting the low–pH‐dependent proteases in the Golgi that would participate in glycosylation of nascent viral proteins. 10 Both of these steps are vital for efficient replication and production of viral products. Clinical trials in patients with human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV‐1) have demonstrated that the addition of chloroquine to existing treatment protocols can decrease the production of infectious particles at doses in the physiologic range for malaria. 11 , 12 This use of chloroquine in HIV‐1 patients has led some authors to speculate on its potential utility in the treatment of other viral infections. 10 If chloroquine were found to be efficacious in vivo, its use would have several attractive features including a unique mechanism of action, lack of cross‐resistance with other antiviral drugs, low cost, and widespread worldwide availability.

The goal of this study was to determine whether chloroquine could decrease morbidity from influenza virus infection in two relevant animal models, the mouse and the ferret. Two viruses were utilized in mice. The mouse‐adapted Mount Sinai strain of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) is an H1N1 subtype virus taken from the influenza virus repository at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. To determine whether findings were subtype specific, a second virus was generated using the eight plasmid reverse genetics system 13 which contains the H3 hemagglutinin (HA) and N2 neuraminidase (NA) from A/Hong/Kong/1/68 (HK68; H3N2) and the six internal genes of PR8 as described. 14 The PR8 backbone was utilized to enhance virulence in mice as the wild‐type parent HK68 causes only mild disease and is not lethal. Both viruses were grown in Madin‐Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Before conducting mouse studies, the susceptibility of these viruses to chloroquine in vitro was assessed. A549 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 with viruses for 48 hours in the presence or absence of 5, 10, or 20 μm of chloroquine. Cells were collected 48 hours post‐infection, stained with Alexa‐488 anti‐HA and surface HA expression was assessed by flow cytometry. As has been reported previously, 7 , 8 chloroquine was effective in vitro, reducing the percentage of cells expressing HA by 56–79% at a 20 μm concentration compared to no treatment, with lesser reductions at 5 and 10 μm (data not shown).

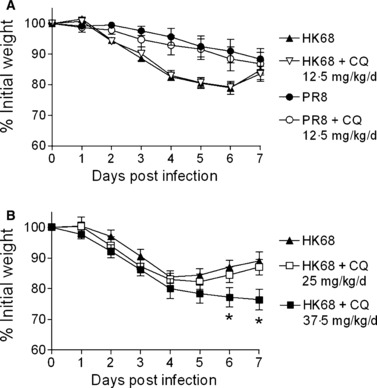

To determine whether chloroquine was effective in vivo, we tested the drug in an established mouse model of infection using age and weight matched groups of 8‐ to 24‐week‐old female Balb/c mice. Chloroquine was given daily starting 24 hours prior to infection with dosing based on prior published protocols evaluating its use protecting mice from CpG and lipopolysaccharide exposure. 15 Groups of nine mice were infected intranasally in a volume of 100 μl sterile PBS while under light isoflurane (2.5% inhaled) anesthesia with either 1 × 103 TCID50 (0.67 MLD50) of PR8 or 1 × 106 TCID50 (1.0 MLD50) of HK68. Mice were treated daily from day −1 through termination of the experiment either intratracheally or orally with 12.5 mg/kg/day of chloroquine in 100 μl of a sucrose vehicle or mock treated with sucrose alone and followed for weight loss. No differences in weight loss were seen on any day post‐infection by anova (P > 0.1) following infection with either virus for intratracheal (Figure 1A) or oral (data not shown) treatment. Following these negative results, dose escalation was attempted using 25 and 37.5 mg/kg/day in groups of five mice after infection with HK68. Again, chloroquine did not improve the weight loss associated with influenza virus infection and, at the highest dose, mice lost significantly more weight on days 6 and 7 when treated with chloroquine compared to the other groups (Figure 1B; P < 0.05 by anova). Thus, chloroquine is not effective at preventing or ameliorating influenza in mice in the dose ranges tested. Influenza virus could not be detected in the lungs of any animals at day 7, indicating that the worsening of disease with the 37.5 mg/kg/day dose was not due to enhanced or prolonged replication of the virus.

Figure 1.

Effect of chloroquine (CQ) on influenza virus infection in mice. (A) Groups of nine mice were infected with influenza viruses PR8 (H1N1) or HK68 (H3N2), dosed with 12.5 mg/kg/day of chloroquine starting 24 hours prior to infection, and followed for weight loss (mean ± SD) compared to mock‐treated animals. (B) Groups of five mice were infected with HK68, dosed with either 25 or 37.5 mg/kg/day of chloroquine starting 24 hours prior to infection, and followed for weight loss compared to mock‐treated animals. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference in weight loss compared to the other groups at that time point (P < 0.05 by anova).

Animal experiments were performed in a BL2 facility in the Animal Resources Center at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH). All experiments were conducted in accordance with guidelines set out by the Animal Care and Use Committee of SJCRH.

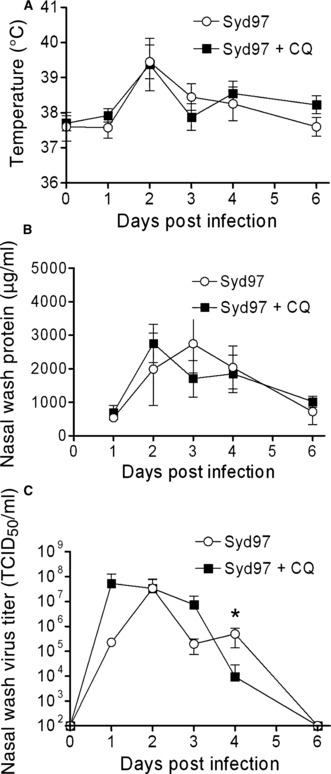

To characterize the effects of chloroquine in a model system that more closely represents human infection we tested the drug in young adult ferrets. Four female young adult (∼700–1000 g) ferrets were given daily oral doses of 10 mg/kg/day chloroquine in a 100 μl volume of sucrose starting 24 hours prior to infection, then infected intranasally with 5 × 105 TCID50 of wild‐type influenza virus A/Sydney/5/97 (Syd97; H3N2), and compared to untreated animals infected and followed in a similar manner. The viral dose is derived from previous ferret studies using this strain, 16 and the chloroquine dose was used to approximate the dose that is given to children for malaria treatment. Ferrets in both groups exhibited clinical signs consistent with influenza including decreased activity, sneezing, and copious nasal discharge. There were no differences in temperature, protein content of the nasal wash, or viral titer in the nasal wash at any day tested except on day 4 when the viral nasal wash titers were significantly higher in the control group than in the chloroquine‐treated group (Figure 2). Overall, however, preventive therapy with chloroquine appeared to have little effect on influenzal infection in ferrets.

Figure 2.

Effect of chloroquine (CQ) on influenza virus infection in ferrets. Groups of four ferrets were infected with Syd97 (H3N2), dosed with 10 mg/kg/day of chloroquine starting 24 hours prior to infection, and compared to untreated animals. (A) Rectal temperatures were monitored daily. Ferrets anesthetized with ketamine had 2 ml of sterile saline introduced into their noses to induce sneezing and the effluent captured in order to assay (B) protein content by the Bradford assay and (C) viral titer on MDCK cells. Values are presented as the mean ± SD. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference in viral titer compared to the other group at that time point (P < 0.05 by anova).

In conclusion, we have found that although chloroquine is effective in vitro at limiting the replication of viruses expressing either an H1 or H3 HA in concurrence with other published reports, 7 , 8 this effect does not extend to in vivo models of influenza. At a concentration of 12.5 mg/kg/day we were not able to protect mice from significant weight loss following infection with either HK68 or PR8. At higher concentrations, the effect of viral infection was enhanced and treated mice lost more weight than mock‐treated animals. Studies exploring the prophylactic effect of chloroquine in a ferret model system that more closely matches human infection likewise did not demonstrate any significant positive effects. It is possible that higher doses of chloroquine or analogs such as hydroxychloroquine with potentially better pharmacokinetics may have a beneficial effect that we were unable to elicit in our models. Studies of combination therapy with current anti‐influenza drugs and chloroquine may also be of use in developing more effective therapies for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza. However, confirmation of the findings of this study in other laboratories is likely to significantly dampen enthusiasm for use of chloroquine as an antiviral against influenza.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Victor Huber for helpful discussion on the topic. This work was supported by ALSAC and NIH AI‐066349.

References

- 1. McCullers JA. Antiviral therapy of influenza. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2005;14:305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stohr K. Preventing and treating influenza. BMJ 2003;326:1223–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bright RA, Shay DK, Shu B, Cox NJ, Klimov AI. Adamantane resistance among influenza A viruses isolated early during the 2005‐2006 influenza season in the United States. JAMA 2006;295:891–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiso M, Mitamura K, Sakai‐Tagawa Y et al. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. Lancet 2004;364:759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Le QM, Kiso M, Someya K et al. Avian flu: isolation of drug‐resistant H5N1 virus. Nature 2005;437:1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keyaerts E, Vijgen L, Maes P, Neyts J, Van RM. In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;323:264–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ooi EE, Chew JS, Loh JP, Chua RC. In vitro inhibition of human influenza A virus replication by chloroquine. Virol J 2006;3:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Trani L, Savarino A, Campitelli L et al. Different pH requirements are associated with divergent inhibitory effects of chloroquine on human and avian influenza A viruses. Virol J 2007;4:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J 2005;2:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Savarino A, Di TL, Donatelli I, Cauda R, Cassone A. New insights into the antiviral effects of chloroquine. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:67–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Romanelli F, Smith KM, Hoven AD. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV‐1) activity. Curr Pharm Des 2004;10:2643–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sperber K, Chiang G, Chen H et al. Comparison of hydroxychloroquine with zidovudine in asymptomatic patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Clin Ther 1997;19:913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoffmann E, Krauss S, Perez D, Webby R, Webster RG. Eight‐plasmid system for rapid generation of influenza virus vaccines. Vaccine 2002;20:3165–3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vigerust DJ, Ulett KB, Boyd KL et al. N‐Linked glycosylation attenuates H3N2 influenza viruses. J Virol 2007;81:8593–8600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hong Z, Jiang Z, Liangxi W et al. Chloroquine protects mice from challenge with CpG ODN and LPS by decreasing proinflammatory cytokine release. Int Immunopharmacol 2004;4:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huber VC, McCullers JA. Live attenuated influenza vaccine is safe and immunogenic in immunocompromised ferrets. J Infect Dis 2006;193:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]