Abstract

Investigation of the bone and the bone marrow is critical in many research fields including basic bone biology, immunology, hematology, cancer metastasis, biomechanics, and stem cell biology. Despite the importance of the bone in healthy and pathologic states, however, it is a largely under-researched organ due to lack of specialized knowledge of bone dissection and bone marrow isolation. Mice are a common model organism to study effects on bone and bone marrow, necessitating a standardized and efficient method for long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation for processing of large experimental cohorts. We describe a straightforward dissection procedure for the removal of the femur and tibia that is suitable for downstream applications, including but not limited to histomorphologic analysis and strength testing. In addition, we outline a rapid procedure for isolation of bone marrow from the long bones via centrifugation with limited handling time, ideal for cell sorting, primary cell culture, or DNA, RNA, and protein extraction. The protocol is streamlined for rapid processing of samples to limit experimental error, and is standardized to minimize user-to-user variability.

Keywords: Immunology, Issue 110, Bone, bone marrow, mouse dissection, bone biology, cancer biology, immunology

Introduction

The study of long bones and the cells of the bone marrow is central to a myriad of research disciplines, including, but not limited to, bone biology, cancer biology, immunology, hematology, and biomechanics. The bone is a highly dynamic organ that together with the cartilage forms the skeleton to provide mechanical support against loading and protection of the internal organs. In addition, the mineral components of bone are a storage sink for the critical signaling molecules calcium and phosphorus, as well as other factors1. Finally, bones house the bone marrow and, together with metabolically active bone forming osteoblasts and bone resorbing osteoclasts, provide the stem cell niche necessary for the maintenance of hematopoietic and lymphoid cell populations.

Bone and bone marrow are affected in many disorders, often leading to bone marrow dysfunction, severe bone pain, and pathologic fracture. Bone is a common site of metastasis in many solid tumors, most notably breast cancer and prostate cancer, where tumor cells directly engage the bone marrow niche to initiate the vicious cycle of bone metastasis and displace hematopoietic stem cells2,3. Hematopoietic malignancies including myeloma and leukemia are characterized by bone marrow dysfunction as well as deregulation of healthy bone remodeling1. Other non-malignant skeletal disorders are also active areas of research, such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, scoliosis, and rickets. Even in an otherwise healthy individual, biomechanical failure in a bone leads to a painful fracture. All of these disorders represent active areas of research with the goal of identifying new preventative measures and treatment regimens to reduce morbidity and mortality.

To research the plethora of roles of the bone and the bone marrow, both under physiologic and pathologic conditions, it is critical for researchers to have a simple and efficient standardized method for dissection of the mouse long bones for rapid processing of large in vivo experiments. The dissection protocol outlined here is suitable for all long bone analyses including ex vivo imaging, histology, histomorphometry, and strength testing, among others. Similarly, a standardized bone marrow isolation method with high bone marrow cell recovery and low inter-user variability is important for experimental analysis such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) as well as downstream applications such as primary cell culture of bone marrow cells.

Protocol

All animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the recommendations outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

1. Hind Limb Long Bone Dissection

Euthanize the mouse in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Position the mouse in a supine position and affix by pinning all four legs through the mouse paw pads below the ankle joint.

Spray the mouse with 70% ethanol, thoroughly dousing the legs.

Make a small incision to the right of midline in the lower abdomen, just above the hip.

Extend the incision down the leg and past the ankle joint.

Pull back the skin and cut the quadriceps muscle anchored to proximal end of the femur to expose the anterior side of the femur and pin out from the leg, placing the pin at a 45-degree angle from the board.

With the blade of the scissors against the posterior side of the femur, cut the hamstrings away from the knee joint.

Pull back the skin and the hamstring muscles anchored to proximal end of the femur to expose the posterior side of the femur and pin out from the leg, placing the pin at a 45-degree angle from the board.

With the forceps, hold the distal end of the femur, just above the knee joint. Guide the blades of the scissors on either side of the femoral shaft towards the hip joint, being careful not to cut into the femur itself.

After reaching the femoral head, indicated by the scissors opening slightly, twist the scissors with the top blade of the scissors moving directly over the femoral head to dislocate the femur, being careful not to snap the bone below the femoral head.

Grasp the top of the femoral shaft with the forceps, cut the soft tissue away from the femoral head to release it from the acetabulum.

Pull the entire leg bone, including femur, knee, and tibia, up and away from the body, carefully cutting away the connective tissue and muscle connecting the leg to the skin.

Overextend the ankle joint and again use the scissors in a twisting motion to dislocate the tibia.

Grasping the distal end of the tibia, taking care not to sever the tendons, pull the tibia up and away from the body and the pin board.

Cut any remaining connective tissue attaching the long bone to the mouse at the knee.

Remove any additional muscle or connective tissue attached to the femur and the tibia.

For any applications that require the bone to remain intact (histology, histomorphometry, biomechanical testing, etc.), proceed with standard in-house protocols (as in 4-7). To isolate bone marrow, proceed to section 2.

2. Long Bone Preparation for Bone Marrow Isolation

Using the forceps, grasp the femur with the patella facing away and the proximal end (femoral head) down.

Overextend the knee joint and use the scissors in a twisting motion to dislocate the tibia and femur.

Cut any connective tissue holding the femur and tibia together.

Using the forceps, grasp the femur with the anterior side facing away and the proximal end (femoral head end) down.

Guide the scissors up the femoral shaft to the condyles.

Gently rotate the scissors back and forth to remove the condyles, the patella, and the epiphysis to expose the metaphysis.

Remove any additional muscle or connective tissue attached to the femur using forceps, scissors, and Kimwipes.

Using the forceps, grasp the tibia with the anterior side facing away and the distal end (ankle end) down.

If the tibial epiphysis is intact, guide the scissors up the tibia shaft to the condyles.

Gently rotate the scissors back and forth to remove the condyles and epiphysis to expose the metaphysis.

Remove any additional muscle or connective tissue attached to the tibia using forceps, scissors, and Kimwipes.

3. Bone Marrow Isolation

Push an 18 G needle through the bottom of a 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tube.

Place the long bones (maximum of 2 femurs and 2 tibiae) into the tube, knee-end down end down and close the lid.

Nest the 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tube in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube.

Centrifuge the nested tubes at ≥10,000 x g in a microcentrifuge for 15 sec.

Verify that the bone marrow has been spun out of the bones by visual inspection. The bones should appear white and there should be a large visual pellet in the larger tube.

Discard the 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tube with the bones.

Suspend the bone marrow in appropriate solution (e.g., PBS, culture media, FACS buffer) and proceed with experimental protocol (DNA, RNA, or protein isolation, FACS analysis, or primary cell culture).

Representative Results

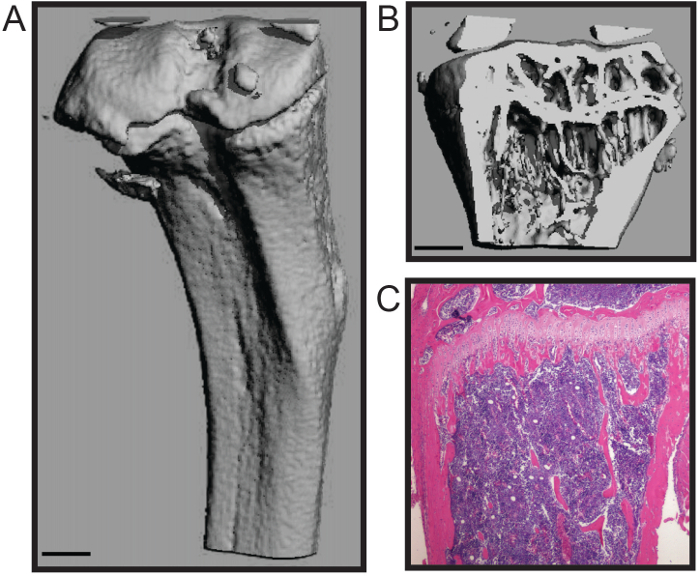

The protocol described here is optimized for rapid dissection of the mouse femur and tibia with a minimum of damage to the bone tissue. This technique is suitable for a number of downstream analyses, including biomechanics studies, histomorphometry (Figure 1A - B), and histology (Figure 1C)4,7. The representative histomophometric micoCT 3D reconstruction (Figure 1A - B) demonstrates that both the cancellous bone and cortical shell are maintained that allows for accurate quantitation of the standardized structural parameters for bone histomorphometry, including trabecular number, thickness, and spacing; bone volume; and cortical thickness, among other measures8. The representative histologic section shows an H&E stained formalin-fixed and decalcified tibia (Figure 1C). The image demonstrates the integrity of both the calcified bone and cellular bone marrow for histologic analysis.

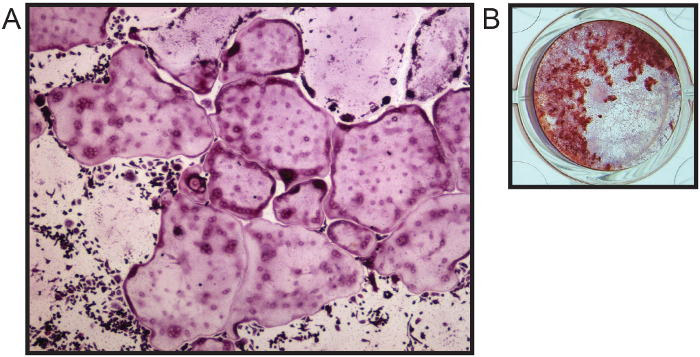

The bone marrow isolation procedure preserves the sterility of the bone marrow space, has low handling to reduce contamination, and does not require cutting of the long bone, thus reducing loss of bone marrow yield. This bone marrow is suitable for many downstream applications, including flow cytometry5 and PCR analyses. In addition, this procedure can be used to isolate bone marrow for primary cell culture of bone marrow cells, including osteoclasts and osteoblasts (Figure 2A - B)4,6.

Figure 1. Histomorphological and Histological Analyses of Mouse Long Bone. Three-dimensional microCT reconstruction of a mouse tibia showing (A) the outer cortical shell and (B) trabecular bone (scale bar = 0.5 mm). (C) Histological H&E stain of a decalcified and sectioned tibia (4x). Images courtesy of Katherine Weilbaecher, Washington University School of Medicine, USA. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 1. Histomorphological and Histological Analyses of Mouse Long Bone. Three-dimensional microCT reconstruction of a mouse tibia showing (A) the outer cortical shell and (B) trabecular bone (scale bar = 0.5 mm). (C) Histological H&E stain of a decalcified and sectioned tibia (4x). Images courtesy of Katherine Weilbaecher, Washington University School of Medicine, USA. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Primary Bone Marrow Cell Culture for Differentiation of Osteoclasts and Osteoblasts. (A) TRAP staining for multinucleated osteoclasts after 7 days in osteoclastogenic media (4x). (B) Alkaline phosphatase (purple color) for osteoblasts and alizarin red (red color) stain for mineralization after 21 days in osteogenic media. Images courtesy of Katherine Weilbaecher, Washington University School of Medicine, USA. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Primary Bone Marrow Cell Culture for Differentiation of Osteoclasts and Osteoblasts. (A) TRAP staining for multinucleated osteoclasts after 7 days in osteoclastogenic media (4x). (B) Alkaline phosphatase (purple color) for osteoblasts and alizarin red (red color) stain for mineralization after 21 days in osteogenic media. Images courtesy of Katherine Weilbaecher, Washington University School of Medicine, USA. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

We present a simple and efficient method for removal of mouse hind long bones and subsequent bone marrow isolation. This method maintains the high structural and cellular integrity of the bones and bone marrow and has low handling time, minimizing the likelihood of user-induced fracture or bone scoring that may influence downstream analyses. In addition, the centrifugation method for isolating bone marrow does not require cutting the bone to expose the bone marrow space or fluid to flush the bone marrow, reducing potential points of contamination. Moreover, the centrifuge technique is relatively high-throughput with lower hands-on time than other methods, thus reducing processing time.

High variation is inherent to in vivo mouse studies due to high mouse-to-mouse phenotypic variation. In order to maximize the research impact of expensive and labor-intensive mouse studies, it is critical to minimize technical experimental error9,10. Time from animal sacrifice to downstream analysis or tissue fixation introduces experimental variation that may overcome subtle changes and reduce large differences between groups. Therefore, rapid processing of samples is essential for accurate data analysis. The long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation techniques described here are optimized for rapid processing of animals and samples to reduce technical variation.

This protocol can be widely applied to many research fields, including investigation of the bone tissue itself or interrogation of the cells of the bone marrow. In addition, this straightforward approach to long bone dissection will enable researchers in related fields to directly interrogate bone contributions in order to expand our knowledge of bone marrow dysfunction in otherwise understudied pathologies.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NCI grant nos. U54CA143803, CA163124, CA093900, and CA143055 to K.J.P. The authors thank the current and past members of the Weilbaecher lab, especially Katherine Weilbaecher, Michelle Hurchla, and Hongju Deng, and members of the Brady Urological Institute, especially members of the Pienta laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- McHayleh WM, Ellerman J, Roodman GD. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. American Socieyt for Bone and Mineral Research; 2008. Ch. 80; pp. 379–381. [Google Scholar]

- Weilbaecher KN, Guise TA, McCauley LK. Cancer to bone: a fatal attraction. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(6):411–425. doi: 10.1038/nrc3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen EA, Shiozawa Y, Pienta KJ, Taichman RS. The prostate cancer bone marrow niche: more than just 'fertile soil. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(3):423–427. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amend SR, et al. Thrombospondin-1 regulates bone homeostasis through effects on bone matrix integrity and nitric oxide signaling in osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(1):106–115. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurchla MA, et al. The epoxyketone-based proteasome inhibitors carfilzomib and orally bioavailable oprozomib have anti-resorptive and bone-anabolic activity in addition to anti-myeloma effects. Leukemia. 2013;27(2):430–440. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch DA, et al. The ARF tumor suppressor regulates bone remodeling and osteosarcoma development in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, et al. The ADP receptor P2RY12 regulates osteoclast function and pathologic bone remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(10):3579–3592. doi: 10.1172/JCI38576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster DW, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley CG, Ellis LM. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483(7391):531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festing MF, Altman DG. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 2002;43(4):244–258. doi: 10.1093/ilar.43.4.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]