Abstract

Remodeling of the distal pulmonary artery wall is a characteristic feature of pulmonary hypertension (PH). In hypoxic PH, the most substantial pathologic changes occur in the adventitia. Here, there is marked fibroblast proliferation and profound macrophage accumulation. These PH fibroblasts (PH-Fibs) maintain a hyperproliferative, apoptotic-resistant, and proinflammatory phenotype in ex vivo culture. Considering that a similar phenotype is observed in cancer cells, where it has been associated, at least in part, with specific alterations in mitochondrial metabolism, we sought to define the state of mitochondrial metabolism in PH-Fibs. In PH-Fibs, pyruvate dehydrogenase was markedly inhibited, resulting in metabolism of pyruvate to lactate, thus consistent with a Warburg-like phenotype. In addition, mitochondrial bioenergetics were suppressed and mitochondrial fragmentation was increased in PH-Fibs. Most importantly, complex I activity was substantially decreased, which was associated with down-regulation of the accessory subunit nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 4 (NDUFS4). Owing to less-efficient ATP synthesis, mitochondria were hyperpolarized and mitochondrial superoxide production was increased. This pro-oxidative status was further augmented by simultaneous induction of cytosolic nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced oxidase 4. Although acute and chronic exposure to hypoxia of adventitial fibroblasts from healthy control vessels induced increased glycolysis, it did not induce complex I deficiency as observed in PH-Fibs. This suggests that hypoxia alone is insufficient to induce NDUFS4 down-regulation and constitutive abnormalities in complex I. In conclusion, our study provides evidence that, in the pathogenesis of vascular remodeling in PH, alterations in fibroblast mitochondrial metabolism drive distinct changes in cellular behavior, which potentially occur independently of hypoxia.

Keywords: mitochondria, complex I, oxidative metabolism, pulmonary hypertension, adventitial fibroblasts

Clinical Relevance

Our study provides evidence that, in the pathogenesis of vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension (PH), alterations in fibroblast mitochondrial metabolism drive distinct changes in cellular behavior, which potentially occur independently of hypoxia. This brings new knowledge to the field of PH and its metabolic theory.

Chronic pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a complex disease characterized by sustained increases in pulmonary vascular resistance, severe obliterative remodeling of the pulmonary arteries, right ventricular dysfunction, and premature death (1). The vascular remodeling observed in PH involves an imbalance of cell proliferation versus cell death and, almost uniformly, persistent inflammation. These observations have led to the hypothesis that the cellular and molecular features of PH resemble hallmark characteristics of cancer (1–6). It is increasingly recognized that changes in cell metabolism in cancer cells, as well as in cells in the surrounding stroma, are essential for cancer cells to proliferate, migrate, and exhibit proinflammatory characteristics. As such, there is an intense effort in the cancer field to define the mechanisms regulating the links between changes in metabolism, growth, and inflammation, as they may offer new opportunities for therapy. Strikingly, metabolic changes, resembling those observed in cancer, have also recently been reported in PH (1, 2, 4, 6, 7). These changes have been described to occur in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (8), endothelial cells (7), and, recently, in fibroblasts (9). These observations support a metabolic hypothesis of PH whereby mitochondrial and cytosolic alterations drive a metabolic adaptation similar to that observed in cancer cells and referred to as Warburg metabolism (described originally for cancer cells, which reprogram metabolic pathways toward aerobic glycolysis to support high proliferation). Recent studies provide evidence that inflammatory activation of immune cells also involves metabolic adaptations that closely resemble those observed by Warburg (6). Therefore, the molecular and functional abnormalities seen in PH cells, including excessive proliferation, apoptosis resistance, and inflammation, might be closely linked to cellular reprogramming of metabolism (7).

Fibroblasts have been recognized to play a critical role within the microenvironment of the vasculature, where they detect and respond to a variety of local environmental stresses, and thereby initiate and coordinate pathophysiological tissue responses, including innate immune/proinflammatory functions (10–14). We have documented that, in both experimental hypoxic PH and human PH, the pulmonary artery adventitia harbors activated fibroblasts (hereafter termed PH-Fibs) with a hyperproliferative, apoptosis-resistant, and proinflammatory phenotype, which persists ex vivo over numerous passages in culture (15–19). Furthermore, in line with the paradigm that stromal cells play a critical role in initiation and perpetuation of vascular inflammation (14, 20–22), we have recently shown that PH-Fibs potently recruit, retain, and activate naive macrophages through paracrine signaling (17, 23). However, at present, no studies have tested the hypothesis that abnormalities in mitochondrial metabolism drive the dramatic phenotypic changes observed in adventitial fibroblasts in PH, and even more importantly, if metabolic alterations can become imprinted and persist ex vivo.

Here, we sought to delineate mitochondrial metabolism in adventitial fibroblasts from chronically hypoxic hypertensive calves and humans with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) demonstrating a hyperproliferative, apoptotic-resistant, and proinflammatory phenotype. We focused our studies on the role of mitochondria in the cellular redox status, as numerous studies have implicated heightened reactive oxygen species (ROS) production as playing a key role in driving the altered phenotype of cells, especially in hypoxic forms of PH (24–26). We studied respiratory parameters of fibroblasts, focusing on intensity and capacity of oxidative phosphorylation along with the activity of respiratory chain complexes, with emphasis on complex I. Employing a variety of redox-sensitive probes, we determined redox status in both the mitochondria and cytosol. We demonstrate the emergence of fibroblast-like cells in both a human and a bovine model of PH, with markedly heightened ROS production secondary to an acquired and persistent defect in complex I that is not simply secondary to hypoxia-induced changes in metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Unless specified otherwise, chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Cultures

Bovine/human pulmonary artery adventitial fibroblasts were isolated from control/donor (CO-Fibs/hCO-Fibs) and hypoxic hypertensive/IPAH (PH-Fibs/hPH-Fibs) calves/humans, as described in the online supplement.

Isolated calf fibroblasts were cultivated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) without glucose supplemented with 4 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, 10% bovine calf serum, nonessential amino acids, and 25 mM glucose. The experiments were performed between four and eight passages. For hypoxic cultivation (5%/38 or 3%/23 mm Hg O2, besides 5% CO2), Scitive N workstation (Ruskinn, Pencoed, UK) was employed.

Immunochemical Semiquantification

Protein detection was performed as described previously (27). Primary antibodies (i.e., translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 23 [Tim23], pyruvate dehydrogenase [PDH], phosphorylated PDH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] Fe-S protein 4 [NDUFS4], nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced oxidase isoform 4 [NOX4], hypoxia-inducible factor [HIF] 1α, oxidative phosphorylation [OXPHOS] cocktail, optic atrophy 1 [autosomal dominant] [OPA1], and mitofusin 2 [MFN2]) all were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Quantitative analysis was performed with Image J software (ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) densitometry.

Conventional Confocal Microscopy

Fibroblasts were cultured on poly-L-lysine–coated glass coverslips. A TCS SP2/SP8 AOBS microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) was employed, using a PL APO 100×/1.4–0.7 oil immersion objective (a pinhole 1 Airy unit). The samples were placed into a thermostable, gas-controlled chamber. LCS software (Leica Microsystems) was used for quantification.

Semiquantification of Matrix Superoxide Release Rate Using Confocal Microscopy

MitoSOX Red (Life Technologies) was used to detect in situ surplus release to the matrix rate of mitochondrial superoxide production (Jm), as described previously (28).

Semiquantification of Cytosolic ROS Levels Using Confocal Microscopy and Spectrofluorometry

For microscopic ROS detection, the cells attached on coverslips were transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing the redox-sensitive heat shock protein 33 (HSP33) protein targeted to FRET probe (29) by Lipofectamine 2,000 (Life Technologies). After 24-hour incubation, the Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) emission was recorded in time. Alternatively, carboxy-2′,7′dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (Life Technologies) was used according to the manual, and fluorescence emission was recorded on an RF PC fluorometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan).

Semiquantification of mitochondrial membrane potential using confocal microscopy was assessed using mitochondrial membrane potential probe (JC1) probe (Life Technologies) (see the online supplement).

Lactate Quantification

Determination of lactate content was based on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide+ reduced (NADH) absorption, as described previously (30).

Isolation of Mitochondria

Mitochondria were isolated using a standard procedure (31).

High-Resolution Respirometry

O2 consumption was measured using an Oxygraph 2k (Oroboros, Innsbruck, Austria) after the air calibration and background correction in cultivation medium (for trypsinized cells) or in respiratory buffer (125 mM sucrose, 65 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM Tris-EGTA, 0.5 mM KPi, 100 μM MgCl2, pH 7,2; for isolated mitochondria). Endogenous respiration was followed by oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor), trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (uncoupler of electron transport chain and ATP synthase), and potassium cyanide (KCN) (cytochrome c oxidase inhibitor) addition, respectively, or in combination. Rotenone/piericidine stepwise titration was used to inhibit respiration from complex I. Mitochondrial respiration was established by 1 mM malate, 5 mM glutamate and pyruvate, and 1 mM ADP.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. The average values (±SD) was plotted. Student’s t test was employed.

Results

Pulmonary Adventitial Fibroblasts from Chronically Hypoxic Hypertensive Calves and Humans (PH-Fibs) Exhibit Decreased Pyruvate Entry to the Krebs Cycle

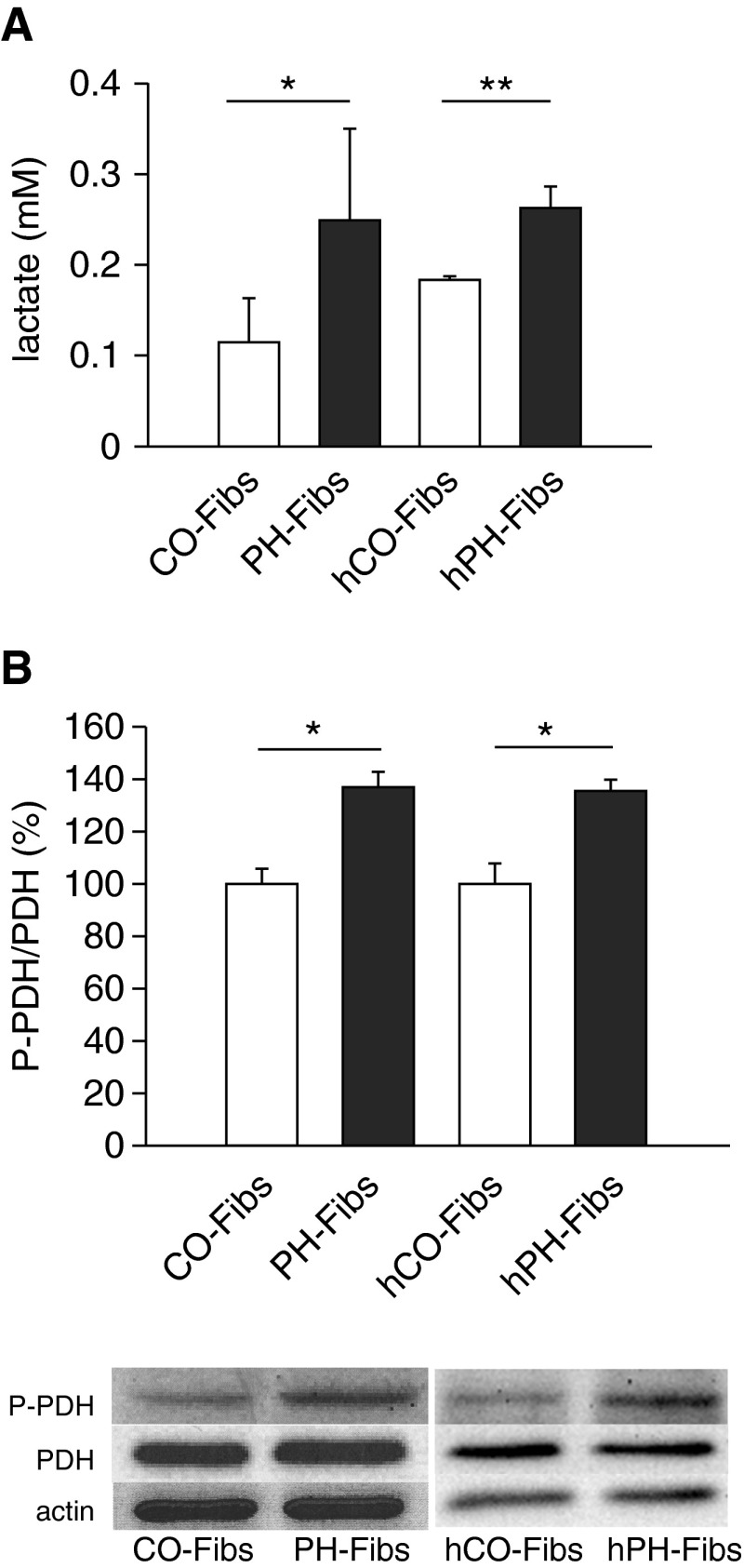

Similar to our previous findings (15–19, 32), all PH-Fibs (both bovine and human) used in these studies demonstrated a significantly higher growth rate than CO-Fibs (data not shown). This raised the possibility that the glycolytic state of these cells would be altered. The glycolytic pathway gives rise to pyruvate as the final product. The pyruvate can then either be converted by PDH to acetyl–coenzyme A (CoA) in mitochondria or by lactate dehydrogenase to lactate in cytoplasm according to PDH phosphorylation status. The latter reaction is typical for fast-proliferating cells, such as cancer cells. Lactate production was found to be increased in PH-Fibs (Figure 1A). Thus, we determined the portion of phosphorylated PDH, which leads to the inhibition of its activity. We found a roughly 30% increase in phosphorylated:nonphosphorylated PDH ratio in both bovine and human PH-Fibs (Figure 1B). Increased PDH phosphorylation restricts influx of pyruvate into the mitochondria of PH-Fibs.

Figure 1.

Warburg phenotype of bovine pulmonary hypertension (PH) and human pulmonary hypertension (hPH) fibroblasts (PH-Fibs/hPH-Fibs). (A) Lactate production in PH-Fibs/hPH-Fibs and control/donor fibroblasts (CO-Fibs/hCO-Fibs) (n = 5/3 for CO-Fibs/hCO-Fibs, n = 7/4 for PH-Fibs/hPH-Fibs). (B) Phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) in PH-Fibs/hPH-Fibs and CO-Fibs/hCO-Fibs expressed as phosphorylated PDH (P-PDH)/total PDH protein ratio (n = 7 and 3 for hFibs). It was quantified by Western blot analysis using specific P-PDH and PDH antibodies. Representative Western blots are shown at the bottom, including control of protein loading (actin quantification). Values are expressed as percentages of the CO-Fibs/hCO-Fibs values. Average values (±SD) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Oxidative Phosphorylation of PH-Fibs Is Diminished and the Mitochondrial Network Is Fragmented

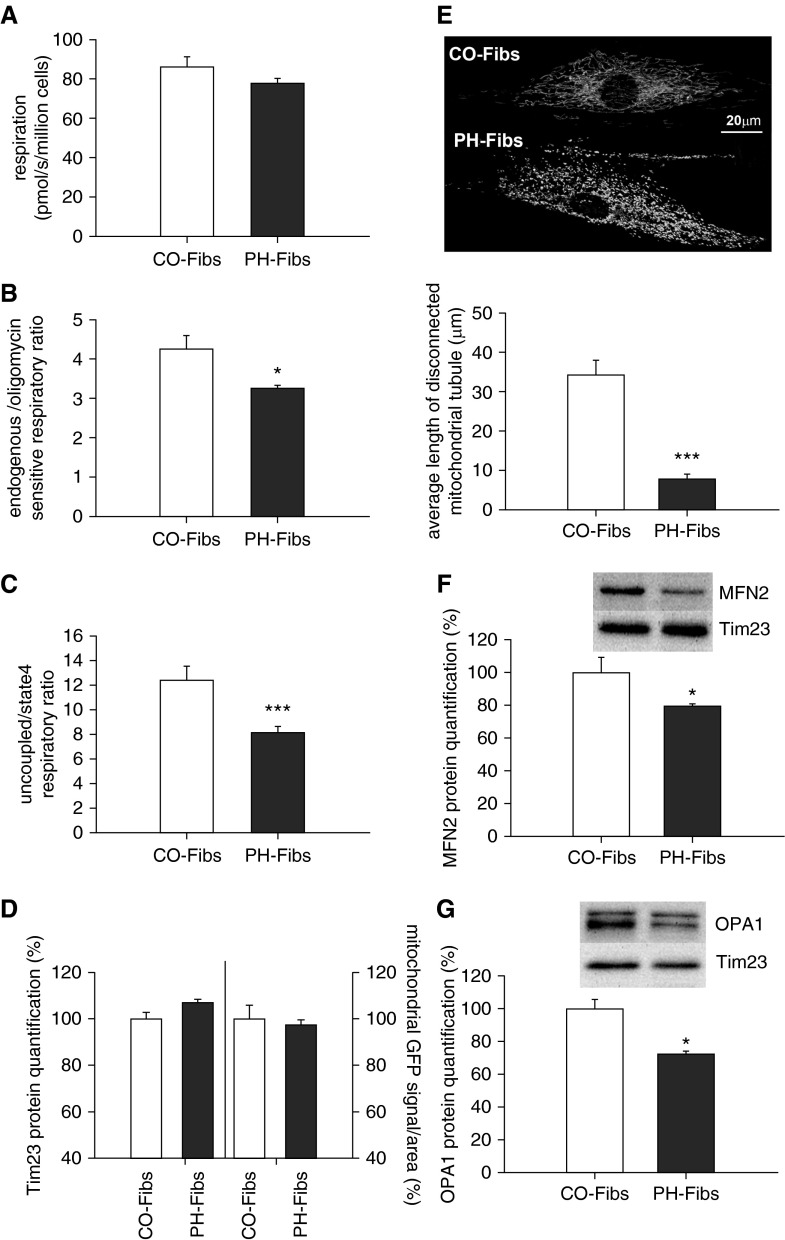

The finding of suppressed pyruvate processing to acetyl-CoA, necessary for feeding the Krebs cycle, prompted us to characterize mitochondrial energy production machinery and respiration in PH-Fibs. The difference in endogenous respiration, (i.e., oxygen consumption) was not statistically different compared with CO-Fibs (Figure 2A). However, the respiratory control ratio, which assesses the potential of ATP synthesis (i.e., mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, within endogenous respiration, showed significant suppression in PH-Fibs; (Figure 2B). An even greater suppression (∼35%) in the maximal respiratory capacity was observed in PH-Fibs (Figure 2C). As these findings might result from a lower mitochondrial mass in PH-Fibs versus CO-Fibs, we quantified the mitochondrial mass by immunocytochemistry with Tim23 antibodies along with mitochondrial green fluorescent protein (GFP) signal quantification using fluorescent confocal microscopy (Figure 2D). We did not detect a significant difference in mitochondrial mass between the two cell populations. Although differences in the amount of respiratory chain complexes in PH-Fibs could also explain the repressed respiratory parameters in PH-Fibs, the total amount of respiratory complexes, represented by specific subunits, was determined, but was not statistically different in PH-Fibs versus CO-Fibs (Figure E2). Moreover, we observed that the mitochondrial network was significantly fragmented in PH-Fibs (Figure 2E). Decreased expression of the fusion proteins, Opa1 and Mfn2, was also found (Figures 2F and 2G).

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial respiratory activity, mass quantification, and mitochondrial morphology of PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs. (A) Endogenous respiration (pmol/s/million cells) of Fibs. (B) Respiratory control ratio expressed as endogenous (state 3)/ATP synthase–inhibited (oligomycin, state 4) respiratory ratio. (C) Maximal respiratory capacity expressed as uncoupled trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP)/ATP synthase–inhibited (oligomycin, state4) respiratory ratio. (D) Quantification of mitochondrial mass by translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 23 (Tim23) protein quantification determined by Western blot analysis using specific Tim23 antibodies and by mitochondria-tagged green fluorescent protein (GFP) signal determination per cell area. (E) Visualization and quantification of mitochondrial fragmentation in PH-Fibs. It was performed by mitochondria-targeted GFP using confocal microscopy. The analysis was done using Amira software (FEI, Hillsboro, Oregon). (F) Quantification of mitofusin 2 (MFN2) fusion protein levels in CO/PH-Fibs. (G) Quantification of optic atrophy 1 (autosomal dominant) (OPA1) fusion protein levels in CO/PH-Fibs. (F and G) Quantification by Western blot analysis using specific MFN2 and OPA1 antibodies. Representative Western blots are shown at the top, including control of protein loading (Tim23 quantification). Values are expressed as percentage of the CO-Fibs values. Average values (±SD) are shown. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Mitochondrial Complex I is Down-Regulated in PH-Fibs, Leading to Mitochondrial Superoxide Production

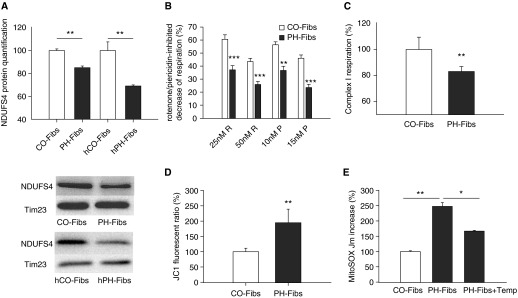

A detailed quantification of each protein complex of respiratory chain separately showed a significant down-regulation of the accessory protein subunit of complex I–NDUFS4 in PH-Fibs (bovine and human) versus CO-Fibs (both bovine and human) (Figure 3A). Deficiencies in this subunit have been shown to be associated with certain neurodegenerative pathologies, excessive inflammation, and cardiomyopathy (33). We investigated the impact of complex I deficiency on respiratory activity in PH-Fibs. We examined complex I activity using both rotenone and piericidine (complex I inhibitors) to evaluate the extent of inhibition of respiration. We found that respiration was decreased in PH-Fibs to a much greater extent compared with CO-Fibs when the same amount of rotenone or piericidine was applied (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Complex I deficiency in PH-Fibs/h PH-Fibs and mitochondrial oxidative status of PH-Fibs. (A) Quantification of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 4 (NDUFS4) subunit of complex I in PH-Fibs/hPH-Fibs and CO-Fibs/hCO-Fibs by Western blot analysis using specific NDUFS4 antibodies. Representative Western blot is shown at the bottom, including control of protein loading (Tim23 quantification). (B) In situ quantification of complex I activity in PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs determined by rotenone (R)/piericidine (P)–inhibited decrease of respiration (100% represents nontreated samples). (C) In vitro quantification of complex I–derived respiratory activity in mitochondria of PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs. (D) Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential in CO-Fibs and PH-Fibs expressed by mitochondrial membrane potential probe (JC1) ratio. The values are expressed as percentage of the CO-Fibs values. (E) Quantification of mitochondrial superoxide in CO-Fibs, PH-Fibs, and PH-Fibs treated with 1 mM tempol for 3 days by MitoSOX fluorescence increase rate, Jm. Values are expressed as percentage of the CO-Fibs values. Average values (±SD) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To directly determine complex I activity in situ, we isolated mitochondria from CO-Fibs and PH-Fibs and performed respiratory measurements using substrates for complex I (glutamate plus malate and pyruvate) and ADP to determine the capacity of oxidative phosphorylation driven through complex I. We found a roughly17% drop in oxygen consumption in PH-Fibs versus Co-Fibs (Figure 3C), which corresponded to the down-regulation of complex I documented in Figure 3A.

Complex I belongs to the proton pumping complexes of the respiratory chain; thus, its decreased activity, in the absence of compensation, must influence proton-motive force and its component, mitochondrial membrane potential. Indeed, we found an approximate twofold increase in fluorescence, reflecting mitochondrial membrane potential, indicating that mitochondria were hyperpolarized in PH-Fibs (Figure 3D). Complex I is also known to comprise one of the major sites of superoxide production within mitochondria. We found an approximate 2.5-fold increase of matrix superoxide release rate of Jm rates in PH-Fibs versus CO-Fibs (Figure 3E).

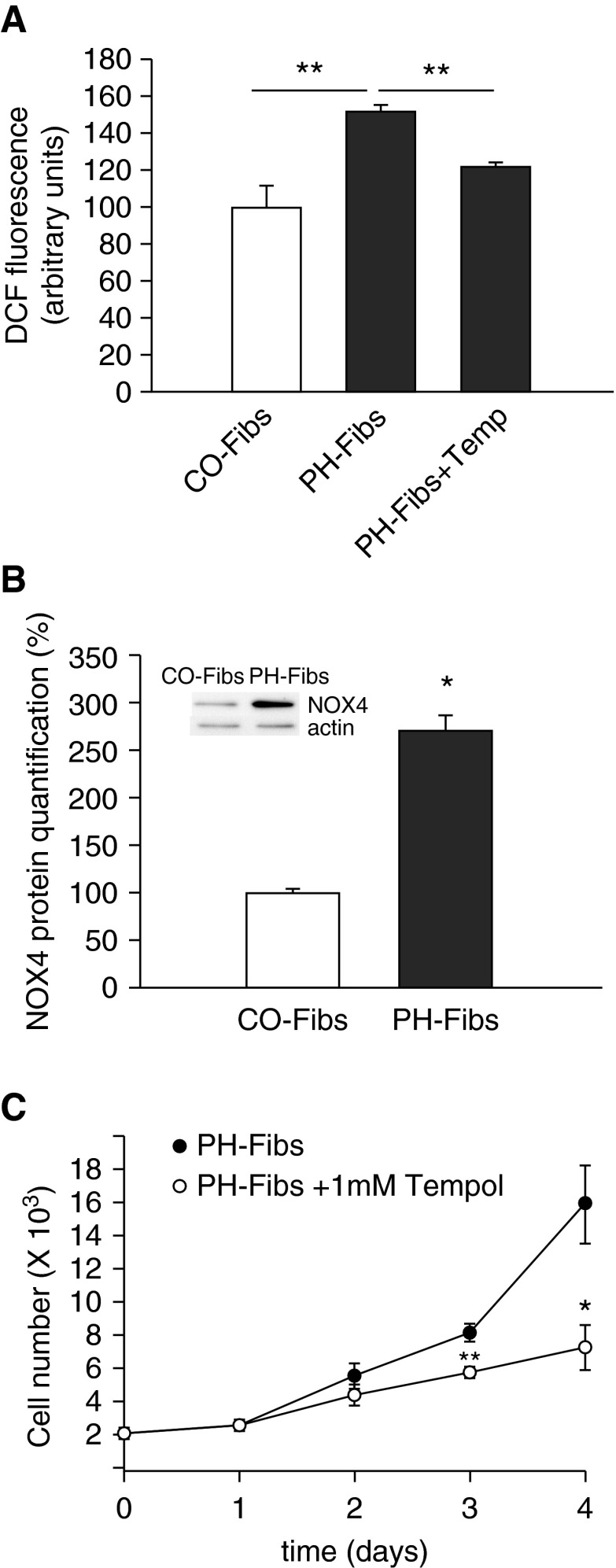

PH-Fibs Exhibit Pro-Oxidative Cellular Status

To elucidate cytosolic redox status in addition to the mitochondrial redox state, we employed both a redox-sensitive HSP33-FRET probe (containing redox-sensitive cysteines) and a nonspecific cell-permeable difluorescein (DCF) probe. Both approaches showed elevation in cytosolic oxidation in PH-Fibs (Figure 4A). As NOX4 has been shown previously to be up-regulated in adventitial fibroblasts in various models of PH (24, 34), we quantified NOX4 protein levels. We observed marked increases in NOX4 expression in PH-Fibs (Figure 4B). The importance of this pro-oxidative status for the hyperproliferative phenotype of PH-Fibs was highlighted by experiments in which PH-Fibs were exposed to antioxidant, tempol. Tempol reduced the proliferative potential of PH-Fibs (Figure 4C) while also decreasing mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS production (Figures 3E and 4A).

Figure 4.

Redox status of cytoplasm in CO-Fibs, PH-Fibs, and PH-Fibs treated with 1 mM tempol for 3 days. (A) Detection of cytosolic oxidation in CO-Fibs, PH-Fibs, and PH-Fibs treated with 1 mM tempol for 3 days using difluorescein (DCF) probe. (B) Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) 4 protein quantification in CO-Fibs and PH-Fibs by protein-normalized Western blot analysis using NOX4-specific antibodies. Values are expressed as percentage of the CO-Fibs values. A representative Western blot is shown at the top. (C) PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs cell proliferation after tempol (1 mM) treatment. Average values (±SD) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Hypoxia Alone Is Not Sufficient to Induce Complex I Deficiency

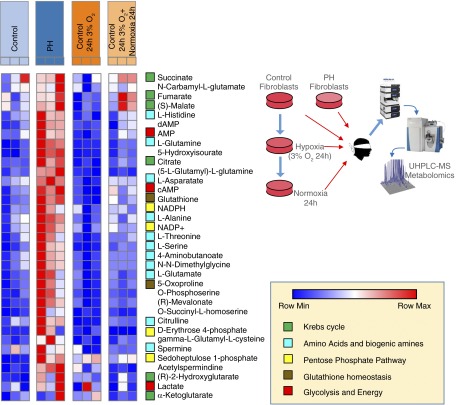

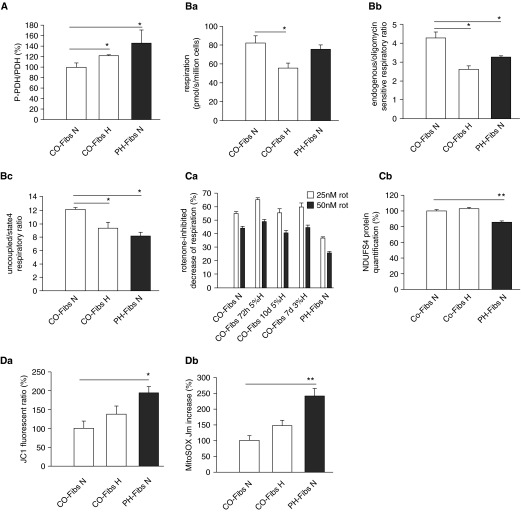

To investigate potential mechanisms responsible for the mitochondrial changes observed in PH-Fibs in vivo, we used an in vitro approach and exposed CO-Fibs to hypoxic conditions (3 and 5% O2) for a minimum of 24 hours, up to 10 days. Metabolic phenotypes of PH and CO-Fibs were assayed through UHPLC–mass spectrometry–based metabolomics, confirming increased levels of lactate, impaired redox homeostasis, and accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates (Figure 5). Exposure to 3% hypoxia for 24 hours promoted transient alterations of the metabolic phenotype of CO-Fibs, which were restored by subsequent exposure to normoxia for 24 hours (Figure 5). We then detected a large (three- to eightfold) increase of the master regulatory transcription factor, HIF1α, in human Fibs (Figure E2). We found an increased phosphorylation of PDH in CO-Fibs exposed to 3 or 5% O2 at all time points examined (Figure 6A). Concurrently, we also observed increased lactate production (Figure 5). We next investigated the effects of hypoxic exposure on mitochondrial energy metabolism. We observed a significant (∼30%) decrease of endogenous respiration of hypoxic CO-Fibs (Figure 6B, a). Similarly, the respiratory control ratio (involvement of oxidative phosphorylation) and maximal respiratory capacity of CO-Fibs were down-regulated in hypoxic conditions (Figure 6B, b and c). To determine whether this was due to down-regulation of mitochondrial mass, we quantified mitochondrial protein by Tim23 immunochemistry. We did not observe significant changes in mitochondrial mass (data not shown) in response to hypoxic conditions. We examined the effect of hypoxia on complex I of the electron transport chain in CO-Fibs, first performing a rotenone inhibitory assay along with quantification of complex I NDUFS4 subunit. We did not find any effect of 3 or 5% O2 exposure for up to 10 days on complex I activity or NDUFS4 protein levels (Figure 6C, a and b). Furthermore, no effects of hypoxia on mitochondrial superoxide production or membrane potential were observed (Figure 6D, a and b). Thus, ex vivo exposure of control fibroblasts to hypoxia alone induced predictable changes toward increased glycolysis and reduced mitochondrial metabolism, but did not cause complex I down-regulation or significant increases in ROS production. Importantly, hypoxia alone was insufficient to have any further effect on PH-Fib mitochondrial metabolism (data not shown). These data suggest that hypoxia alone and hypoxia-induced HIF1 signaling is insufficient to induce the complex I alterations observed in PH-Fibs, and that metabolic reprogramming observed in PH-Fibs is not explained by the effect of hypoxia alone.

Figure 5.

PH-Fibs are characterized by distinct metabolic phenotypes in comparison to CO-Fibs, hypoxic CO-Fibs, and transiently hypoxic CO-Fibs. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)–mass spectrometry (MS) metabolomics analyses were performed on CO-Fibs and PH-Fibs. Relative metabolite quantities were graphed through heat maps, upon Z score normalization of values determined across samples (blue, lowest values; red, highest values). In agreement with the other measurements, metabolomics analyses confirmed that PH-Fibs were characterized by significant alterations of glycolysis, Krebs cycle, redox homeostasis (glutathione homeostasis and pentose phosphate pathway), and amino acid metabolism. Hypoxia (3% O2 for 24 h) or reoxygenation of hypoxic CO-Fibs were not sufficient to mimic the extreme metabolic derangement observed in PH-Fibs in the tested time window. Metabolic pathways were color coded, as detailed in the bottom right chart. Each sample is represented by three independent experiments depicted in columns.

Figure 6.

State of glycolytic switch, mitochondrial parameters, complex I, and mitochondrial oxidation in normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs kept in 3 or 5% hypoxia for up to 10 days. (A) Phosphorylation of PDH in normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs kept in 72-hour hypoxia (5% O2) expressed as P-PDH:PDH protein ratio. It was quantified by protein-normalized Western blot analysis using specific P-PDH and PDH antibodies. (B) Respiratory parameters under 72-hour hypoxia (5% O2). (Ba) Endogenous respiration (pmol/s/million cells) of normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-FIBs in 72-hour hypoxia (5% O2). (Bb) Respiratory control ratio expressed as endogenous (state 3)/ATP synthase–inhibited (oligomycin, state 4) respiratory ratio. (Bc) Maximal respiratory capacity expressed as uncoupled (FCCP)/ATP synthase–inhibited (oligomycin, state 4) respiratory ratio. (C) Complex I state under hypoxia. (Ca) In situ quantification of complex I activity in normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs kept in 72-hour/10-day hypoxia (5% O2) or 7-day hypoxia (3% O2) determined by rotenone-inhibited decrease of respiration. (Cb) Quantification of NDUFS4 subunit of complex I in normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs kept in 72-hour hypoxia (5% O2) by Western blot analysis using specific NDUFS4 antibodies. (D) Mitochondrial redox state under hypoxia. (Da) Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential in normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs kept in 72-hour hypoxia (5% O2) expressed by JC1 ratio. (Db) Quantification of mitochondrial superoxide in normoxic CO/PH-Fibs and CO-Fibs kept in 72-hour hypoxia (5% O2) by MitoSOX fluorescence increase rate, Jm. (A, C, and D) Values are expressed as percentage of the normoxic CO-Fibs values. Average values (±SD) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Paracrine Signaling by PH-Fib–Activated Macrophages Does Not Induce Mitochondrial Dysfunction of CO-Fibs Ex Vivo

We previously reported that PH-Fibs induce a distinct proinflammatory, profibrotic phenotype in macrophages. These fibroblast-activated macrophages, in turn, can stimulate proliferation of control fibroblasts and SMCs. To determine whether fibroblast-activated macrophages can contribute to complex I suppression in control fibroblasts ex vivo, we cocultured CO-Fibs with supernatant from PH-Fib–activated macrophages under normoxic conditions. Within the experimental time frame, we did not observe any changes in complex I subunit protein amount (data not shown) compared with untreated CO-Fibs.

Suppression of PDH Inhibition in PH-Fibs Does Not Correct Energy and Redox Metabolism

PH-Fibs exhibit suppressed influx of pyruvate to mitochondria due to inhibition of PDH compared with CO-Fibs. As dichloroacetate (DCA) is a widely used pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) inhibitor, and has even been proposed as a treatment for patients with PAH (6), we wanted to determine if DCA could restore mitochondrial bioenergetics and redox homeostasis in PH-Fibs. We found that, although DCA treatment of PH-Fibs decreased inhibition of PDH and suppressed cell proliferation, mitochondrial endogenous respiration did not show any increase in oxygen consumption, indicating continued complex I dysfunction and persistent mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS production (Figure E1).

Discussion

Here, we show that persistent alterations in mitochondrial metabolism, specifically in complex I, characterize the hyperproliferative, apoptotic-resistant, and proinflammatory adventitial fibroblasts derived from the remodeled pulmonary arteries of hypoxic calves and humans with IPAH. Mitochondrial energy metabolism of PH-Fibs is also decreased, which, together with down-regulation of complex I, leads to increased mitochondrial superoxide production. Furthermore, this pro-oxidative mitochondrial metabolism is accompanied by increased cytosolic ROS production, which our data suggest is most probably due to NOX4. Importantly, our data functionally link these metabolic changes to cellular function, as we show markedly decreased proliferation of PH-Fibs upon treatment with the ROS scavenger, tempol.

An additional important observation of our studies is that mitochondrial respiratory parameters were decreased in PH-Fibs, even under normoxic conditions. Mechanistically, decreased mitochondrial respiration can potentially be attributed to enhanced phosphorylation of PDH, resulting in its inhibition. PDH acts as a gatekeeper enzyme for the entry of pyruvate produced by glycolysis into the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle by converting it to acetyl-CoA and thus regulating mitochondrial metabolism. PDH phosphorylation has been shown to be regulated by hypoxia, as HIF1 increases the expression and activity of PDH kinase, which increases PDH phosphorylation (35). Interestingly, our studies suggest that hypoxia alone, and HIF1 signaling in response to hypoxia, likely do not contribute to this metabolic alteration in PH-Fibs. In contrast, we observed a critical role for HIF1 and hypoxia in controlling PDK, and thus pyruvate flux, in fibroblasts exposed to hypoxia. Exposing CO-Fibs to hypoxia ex vivo was sufficient to decrease mitochondrial respiratory parameters through enhancement of PDH phosphorylation, but did not promote the extreme metabolic reprogramming observed in normoxic PH-Fibs, nor did it lead to a complex I deficiency in a 24-hour to 10-day time window, respectively. These data suggest that in vivo hypoxia alone and increased HIF1 signaling in response to hypoxia are insufficient to promote the activated PH-Fib phenotype. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis regarding cellular activation of inflammatory macrophages exhibiting similar metabolic alterations (36). Current data suggest that signals within the microenvironment, such as lactate, cytokines, and danger signals alone or in combination with hypoxia, but likely not hypoxia alone, are important regulators of cellular metabolic programs that allow inflammatory activation. Thus, microenvironmental signals within the adventitia, in addition to hypoxia, are likely driving the PH-Fib phenotype. In addition, as we have previously shown for inflammatory macrophages, HIF1 signaling can be increased by a variety of factors (e.g., lactate, IL-6 [6, 23, 36]). However, the exact microenvironmental signals that induce and maintain cellular changes in metabolism remain elusive. We have therefore begun to address this question in part in the present study by exposing control fibroblasts to soluble factors derived from fibroblast-activated macrophages. Unfortunately, these experiments did not induce metabolic alterations in control fibroblasts that would recapitulate the PH-Fib metabolic phenotype. Therefore, future studies are required to define the local adventitial microenvironment in situ to find potential molecular mediators that induce PH-Fib metabolic changes.

Furthermore, the induction of pyruvate entry to mitochondria by DCA treatment of PH-Fibs did not correct either mitochondrial metabolism or complex I alterations, although it significantly decreased the proliferative potential of PH-Fibs. This indicates that DCA treatment is not able to correct all of the cell phenotypes that emerge and are associated with PH development. Thus, the decrease in complex I activity in PH-Fibs cannot be explained simply by a hypoxia-induced decrease of pyruvate entry into the mitochondria. Rather, we found that the reduced activity of complex I was caused by down-regulation of one of its accessory subunits, NDUFS4, which might then affect the complex assembly.

In the bovine species, complex I consists of 45 different subunits that combine into the complex I holo-complex to form an approximately 1 megadaltons MD assembly. Seven complex I subunits originate from mitochondrial DNA, and the rest from the nuclear DNA. NDUFS4 is a nuclear-encoded subunit, which, once phosphorylated by cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) in the cytosol on its C-terminal end of the protein (37), promotes import and maturation of the precursor protein, which then incorporates into the core complex of complex I and enables its proper activity. Pathological mutations in the human NDUFS4 gene result in the disappearance of the protein encoded by the gene, failure of the final step of complex I assembly, and suppression of the NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase activity (38). Complex I dysfunction is frequently associated with abnormalities of inflammation and cardiac dysfunction (39, 40). Thus, we suggest that NDUFS4 might be a significant player in the mitochondrial abnormalities observed in cells that are important in PH development.

In PH-Fibs, the activity of complex I is decreased, leading to an increase in the proton-motive force. The proton pumping in complexes III and IV must then substitute for the deficiency in complex I, leading to increased proton-motive force and its mitochondrial membrane potential component. Note also that less-efficient ATP synthesis giving the lower H+ backflow via the ATP-synthase F0 moiety also leads to the observed increase in membrane potential. The elevated leak of electrons from the mitochondrial respiratory chain at NADH>>NAD+ and the reaction of these electrons with molecular oxygen lead to increased superoxide production. Of note, complex I is one of the major superoxide-producing sites in the mitochondria (41), with the resultant ROS production localized to the mitochondrial matrix. These observations thus establish the increased pro-oxidative features of mitochondria in PH-Fibs. In addition, the complex I malfunction in humans derived from a reduced level or a complete absence of fully assembled complex I has been shown to induce mitochondrial ROS formation (42).

We also found that NOX4, the only constitutively active NOX isoform, is increased in PH-Fibs. In parallel, the increased oxidative status in the cytosol can be linked to NOX4 activity in PH-Fibs. Recently, this isoform was expressed in endothelium and adventitia during development of PH in rat models of PAH (34). That study showed that increased expression of NOX4 in the absence of other stimuli was sufficient to increase fibroblast migration and proliferation; and inhibition of NOX4 activity reduced cellular proliferation. Similarly, we observed that suppressing the pro-oxidative status in PH-Fibs using the antioxidant, tempol, a superoxide dismutase mimetic and pleiotropic intracellular antioxidant, decreased their proliferative potential. Thus, pro-oxidative metabolism of PH-Fibs comprising mitochondrial and/or cytosolic sources might be crucial for proliferation and thus remodeling of the artery. However, the exact contribution of either ROS sources to PH development remains to be elucidated. The importance of pro-oxidative metabolism in PH is supported by studies where suppression of oxidative metabolism, including the use of tempol, leads to the reduction of PH development (24–26, 43–45).

We also show that the mitochondrial network of PH-Fibs is significantly fragmented, with associated changes in the expression of the mitochondrial fusion proteins, OPA1 and MFN2. The fragmentation of mitochondria in PH-Fibs corresponds with observations in other cells from the pulmonary hypertensive vessel wall (46). However, in addition to the altered expression levels of these proteins, the fusion/fission of mitochondria is also regulated by post-translational modifications of the proteins mentioned previously here, their mitochondrial recruitment, presence of cofactors, and membrane lipid composition (47). The significance of a fragmented mitochondrial network in PH-Fibs with mitochondrial suppressed oxidative phosphorylation and pro-oxidative metabolism remains to be investigated.

The adventitia comprises a loosely defined array of cells, including fibroblasts, collagen, and elastic fibers and immune cells that encircle the tunica media and intima layers of the blood vessel. The adventitia, thus, is capable of orchestrating inflammation and vascular proliferation in response to any incoming insult, such as chronic hypoxia, and therefore playing an important role in the induction of PH. In response to many stimuli, fibroblasts, likely specific subpopulations, secrete growth factors, chemokines, and inflammatory cytokines (16). The precise mechanisms controlling such secretion have not been well defined. However, the secretion of soluble factors could be regulated by the pro-oxidative status of the PH-Fibs represented by hydrogen peroxide as a mediator of signaling or deficiency of complex I alone (40–42). Interestingly, complex I deficiency has been found to be the most common disorder of the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system in human pathologies (48). However, complex I defects have not yet been described in other cell types involved in the remodeling of the pulmonary artery wall during PH development, such as SMCs and endothelial cells. In these cells, mitochondria were shown to be hyperpolarized, with a restricted influx of carbohydrates, and thus mitochondrial energy metabolism is suppressed and cells are apoptosis resistant (4). Further studies need to be directed at investigating the relevance of complex I disorders in PH. Do complex I defects simply initiate a pro-oxidative signaling through mitochondria (e.g., for regulation of inflammation and/or proliferation), or does complex I deficiency regulate further signaling through decreased oxidative phosphorylation? The oxidative signaling derived from complex I deficiency was shown to be relevant in studies with stable down-regulation of a single subunit of complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A13 [GRIM-19] or NDUFS3) in HeLa cells, decreasing its activity, leading to enhanced cell adhesion, migration, and invasion, and thus influencing the expression of extracellular matrix molecules and playing a role in cancer metastasis (49). It is possible that cells exhibiting a variety of mitochondrial abnormalities will exist during the development of PH. It will be important to ultimately determine whether and if these abnormalities can or should be targeted therapeutically.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The help of Jana Vaicova with Western blotting, Hana Engstová with Amira software (FEI, Hillsboro, OR), and Marcia McGowan with EndNote software are gratefully acknowledged. The collaboration between the U.S. and Czech partners was initiated by Petr Paucek (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) program project grant 5 P01 HL014985-40A1, NIH R01 grant 1 R01 HL125827-01, and Department of Defense grant PR140977 (K.R.S.), and by Czech Ministry of Education KONTAKT grants LH 11055 and LH 15071 (L.P.-H.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design—L.P.-H. and K.R.S.; analysis and interpretation—L.P.-H., J.T., M.L., A.D’A., K.C.E.K., P.J., and K.R.S.; performance of experiments—L.P.-H., J.T., M.L., H.Z., A.R.F., S.S.P., P.C., A.D’A., and K.C.E.K.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0142OC on December 23, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Tuder RM, Archer SL, Dorfmüller P, Erzurum SC, Guignabert C, Michelakis E, Rabinovitch M, Schermuly R, Stenmark KR, Morrell NW. Relevant issues in the pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25) suppl:D4–D12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottrill KA, Chan SY. Metabolic dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension: the expanding relevance of the Warburg effect. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:855–865. doi: 10.1111/eci.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulin R, Michelakis ED. The metabolic theory of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;115:148–164. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.301130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuder RM, Davis LA, Graham BB. Targeting energetic metabolism: a new frontier in the pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:260–266. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1536PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stenmark KR, Tuder RM, El Kasmi KC. Metabolic reprogramming and inflammation act in concert to control vascular remodeling in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015;119:1164–1172. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00283.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fijalkowska I, Xu W, Comhair SA, Janocha AJ, Mavrakis LA, Krishnamachary B, Zhen L, Mao T, Richter A, Erzurum SC, et al. Hypoxia inducible-factor1α regulates the metabolic shift of pulmonary hypertensive endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1130–1138. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMurtry MS, Bonnet S, Wu X, Dyck JR, Haromy A, Hashimoto K, Michelakis ED. Dichloroacetate prevents and reverses pulmonary hypertension by inducing pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circ Res. 2004;95:830–840. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145360.16770.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao L, Chen CN, Hajji N, Oliver E, Cotroneo E, Wharton J, Wang D, Li M, McKinsey TA, Stenmark KR, et al. Histone deacetylation inhibition in pulmonary hypertension: therapeutic potential of valproic acid and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. Circulation. 2012;126:455–467. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baglole CJ, Ray DM, Bernstein SH, Feldon SE, Smith TJ, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. More than structural cells, fibroblasts create and orchestrate the tumor microenvironment. Immunol Invest. 2006;35:297–325. doi: 10.1080/08820130600754960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barone F, Nayar S, Buckley CD. The role of non-hematopoietic stromal cells in the persistence of inflammation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:416. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flavell SJ, Hou TZ, Lax S, Filer AD, Salmon M, Buckley CD. Fibroblasts as novel therapeutic targets in chronic inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:S241–S246. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RS, Smith TJ, Blieden TM, Phipps RP. Fibroblasts as sentinel cells: synthesis of chemokines and regulation of inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:317–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenmark KR, Yeager ME, El Kasmi KC, Nozik-Grayck E, Gerasimovskaya EV, Li M, Riddle SR, Frid MG. The adventitia: essential regulator of vascular wall structure and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:23–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anwar A, Li M, Frid MG, Kumar B, Gerasimovskaya EV, Riddle SR, McKeon BA, Thukaram R, Meyrick BO, Fini MA, et al. Osteopontin is an endogenous modulator of the constitutively activated phenotype of pulmonary adventitial fibroblasts in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L1–L11. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00050.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das M, Burns N, Wilson SJ, Zawada WM, Stenmark KR. Hypoxia exposure induces the emergence of fibroblasts lacking replication repressor signals of PKCzeta in the pulmonary artery adventitia. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:440–448. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Riddle SR, Frid MG, El Kasmi KC, McKinsey TA, Sokol RJ, Strassheim D, Meyrick B, Yeager ME, Flockton AR, et al. Emergence of fibroblasts with a proinflammatory epigenetically altered phenotype in severe hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J Immunol. 2011;187:2711–2722. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panzhinskiy E, Zawada WM, Stenmark KR, Das M. Hypoxia induces unique proliferative response in adventitial fibroblasts by activating PDGFβ receptor-JNK1 signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:356–365. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Zhang H, Li M, Frid MG, Flockton AR, McKeon BA, Yeager ME, Fini MA, Morrell NW, Pullamsetti SS, et al. MicroRNA-124 controls the proliferative, migratory, and inflammatory phenotype of pulmonary vascular fibroblasts. Circ Res. 2014;114:67–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barron L, Smith AM, El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Huang X, Cheever A, Borthwick LA, Wilson MS, Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Role of arginase 1 from myeloid cells in Th2-dominated lung inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barberà JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, Jones PL, Maitland ML, Michelakis ED, Morrell NW, et al. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1) suppl:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenmark KR, Frid MG, Yeager M, Li M, Riddle S, McKinsey T, El Kasmi KC. Targeting the adventitial microenvironment in pulmonary hypertension: a potential approach to therapy that considers epigenetic change. Pulm Circ. 2012;2:3–14. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.94817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Kasmi KC, Pugliese SC, Riddle SR, Poth JM, Anderson AL, Frid MG, Li M, Pullamsetti SS, Savai R, Nagel MA, et al. Adventitial fibroblasts induce a distinct proinflammatory/profibrotic macrophage phenotype in pulmonary hypertension. J Immunol. 2014;193:597–609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adesina SE, Kang BY, Bijli KM, Ma J, Cheng J, Murphy TC, Michael Hart C, Sutliff RL. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species to modulate hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;87:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mittal M, Roth M, König P, Hofmann S, Dony E, Goyal P, Selbitz AC, Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Kwapiszewska G, et al. Hypoxia-dependent regulation of nonphagocytic NADPH oxidase subunit NOX4 in the pulmonary vasculature. Circ Res. 2007;101:258–267. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waypa GB, Marks JD, Guzy R, Mungai PT, Schriewer J, Dokic D, Schumacker PT. Hypoxia triggers subcellular compartmental redox signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2010;106:526–535. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assay-ProtocolWestern-blot protocol. Biology Assays & Protocols. Available from: www.assay-protocol.com

- 28.Dlasková A, Hlavatá L, Jezek J, Jezek P. Mitochondrial complex I superoxide production is attenuated by uncoupling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2098–2109. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, Simon MC, Hammerling U, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 2005;1:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem J. 1967;103:514–527. doi: 10.1042/bj1030514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frezza C, Cipolat S, Scorrano L. Organelle isolation: functional mitochondria from mouse liver, muscle and cultured fibroblasts. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:287–295. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frid MG, Li M, Gnanasekharan M, Burke DL, Fragoso M, Strassheim D, Sylman JL, Stenmark KR. Sustained hypoxia leads to the emergence of cells with enhanced growth, migratory, and promitogenic potentials within the distal pulmonary artery wall. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1059–L1072. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90611.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koene S, Rodenburg RJ, van der Knaap MS, Willemsen MA, Sperl W, Laugel V, Ostergaard E, Tarnopolsky M, Martin MA, Nesbitt V, et al. Natural disease course and genotype–phenotype correlations in complex I deficiency caused by nuclear gene defects: what we learned from 130 cases. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:737–747. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9492-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barman SA, Chen F, Su Y, Dimitropoulou C, Wang Y, Catravas JD, Han W, Orfi L, Szantai-Kis C, Keri G, et al. NADPH oxidase 4 is expressed in pulmonary artery adventitia and contributes to hypertensive vascular remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1704–1715. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1–mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Neill LA, Hardie DG. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature. 2013;493:346–355. doi: 10.1038/nature11862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Rasmo D, Signorile A, Larizza M, Pacelli C, Cocco T, Papa S. Activation of the cAMP cascade in human fibroblast cultures rescues the activity of oxidatively damaged complex I. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scacco S, Petruzzella V, Budde S, Vergari R, Tamborra R, Panelli D, van den Heuvel LP, Smeitink JA, Papa S. Pathological mutations of the human NDUFS4 gene of the 18-kDa (AQDQ) subunit of complex I affect the expression of the protein and the assembly and function of the complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44161–44167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chouchani ET, Methner C, Buonincontri G, Hu CH, Logan A, Sawiak SJ, Murphy MP, Krieg T. Complex I deficiency due to selective loss of Ndufs4 in the mouse heart results in severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin Z, Wei W, Yang M, Du Y, Wan Y. Mitochondrial complex I activity suppresses inflammation and enhances bone resorption by shifting macrophage–osteoclast polarization. Cell Metab. 2014;20:483–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roestenberg P, Manjeri GR, Valsecchi F, Smeitink JA, Willems PH, Koopman WJ. Pharmacological targeting of mitochondrial complex I deficiency: the cellular level and beyond. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kamezaki F, Tasaki H, Yamashita K, Tsutsui M, Koide S, Nakata S, Tanimoto A, Okazaki M, Sasaguri Y, Adachi T, et al. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase ameliorates pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:219–226. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-264OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lachmanová V, Hnilicková O, Povýsilová V, Hampl V, Herget J. N-acetylcysteine inhibits hypoxic pulmonary hypertension most effectively in the initial phase of chronic hypoxia. Life Sci. 2005;77:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soon E, Crosby A, Southwood M, Yang P, Tajsic T, Toshner M, Appleby S, Shanahan CM, Bloch KD, Pepke-Zaba J, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II deficiency and increased inflammatory cytokine production: a gateway to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:859–872. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1509OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan J, Dasgupta A, Huston J, Chen KH, Archer SL. Mitochondrial dynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015;93:229–242. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kasahara A, Scorrano L. Mitochondria: from cell death executioners to regulators of cell differentiation. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smeitink J, van den Heuvel L, DiMauro S. The genetics and pathology of oxidative phosphorylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:342–352. doi: 10.1038/35072063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He X, Zhou A, Lu H, Chen Y, Huang G, Yue X, Zhao P, Wu Y. Suppression of mitochondrial complex I influences cell metastatic properties. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]