Abstract

Pulmonary edema occurs in settings of acute lung injury, in diseases, such as pneumonia, and in acute respiratory distress syndrome. The lung interendothelial junctions are maintained in part by vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, an adherens junction protein, and its surface expression is regulated by endocytic trafficking. The Rab family of small GTPases are regulators of endocytic trafficking. The key trafficking pathways are regulated by Rab4, -7, and -9. Rab4 regulates the recycling of endosomes to the cell surface through a rapid-shuttle process, whereas Rab7 and -9 regulate trafficking to the late endosome/lysosome for degradation or from the trans-Golgi network to the late endosome, respectively. We recently demonstrated a role for the endosomal adaptor protein, p18, in regulation of the pulmonary endothelium through enhanced recycling of VE-cadherin to adherens junction. Thus, we hypothesized that Rab4, -7, and -9 regulate pulmonary endothelial barrier function through modulating trafficking of VE-cadherin–positive endosomes. We used Rab mutants with varying activities and associations to the endosome to study endothelial barrier function in vitro and in vivo. Our study demonstrates a key role for Rab4 activation and Rab9 inhibition in regulation of vascular permeability through enhanced VE-cadherin expression at the interendothelial junction. We further showed that endothelial barrier function mediated through Rab4 is dependent on extracellular signal–regulated kinase phosphorylation and activity. Thus, we demonstrate that Rab4 and -9 regulate VE-cadherin levels at the cell surface to modulate the pulmonary endothelium through extracellular signal–regulated kinase–dependent and –independent pathways, respectively. We propose that regulating select Rab GTPases represents novel therapeutic strategies for patients suffering with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Keywords: endocytosis, Rab GTPase, endothelium, vascular endothelial-cadherin, acute respiratory distress syndrome

Clinical Relevance

The role of the endosome on the pulmonary endothelium is a novel and emerging area of research. The studies presented here demonstrate that modulation of endosome proteins significantly reduces the damage to the pulmonary endothelium in settings of bacteria-induced pulmonary edema.

Despite substantial improvements in supportive care, such as mechanical ventilation, acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with sepsis and severe pneumonia (1). ARDS occurs through transudation of fluid and protein from the pulmonary microvasculature into alveolar air spaces and interstitium, resulting in impaired gas exchange, reduced lung compliance, and sequestration of leukocytes in lung tissue and, finally, pulmonary edema (2). Increased endothelial permeability is therefore an important contributing factor in the development of pulmonary edema. Pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells form a tight barrier, maintained largely by adherens junctions (AJs), which is resistant to the paracellular movement of proteinaceous fluid and inflammatory cells. AJs are formed from the calcium-dependent homotypic interactions of vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin from neighboring cells (3). The extracellular domain of VE-cadherin forms the AJ, and the cytoplasmic tail of VE-cadherin anchors the actin cytoskeleton via p120-catenin and β-catenin (4). These protein–protein interactions are essential for maximum strength and stability of AJs and thus maintenance of endothelial barrier function (5, 6). Stabilization of VE-cadherin at the AJ, through genetic manipulation of VE-cadherin–catenin interactions, attenuates pulmonary vascular leakage in an LPS-induced in vivo model of ARDS (7, 8). Therefore manipulation of VE-cadherin at the cell–cell junction alters endothelial barrier function with potential implications for the pathogenesis of ARDS.

Expression of cadherins at intercellular junctions is regulated by internalization and recycling back to the cell surface (9, 10). Although cadherin trafficking is known to influence permeability of epithelium, studies are lacking regarding this process in the endothelium. Enhanced internalization of VE-cadherin, and the resulting rise in vascular permeability, has been observed in endothelial cells after exposure to vascular endothelial growth factor or LPS (9, 11). We have recently demonstrated a role for the novel endocytic adaptor protein, p18, in increasing VE-cadherin levels at the endothelial cell surface and VE-cadherin–catenin interactions concomitant with enhanced endothelial barrier integrity (11). Furthermore, we demonstrate that, through binding the early endosome, p18 attenuates LPS-induced barrier disruption in vitro and in vivo (11). Thus, regulated trafficking of VE-cadherin–positive endosomes may represent a novel mechanism to maintain a tight endothelial barrier in settings of ARDS; however, the mechanisms regulating VE-cadherin–positive endosome trafficking is still not well understood.

The small GTPase family, Ras related in brain (Rab) GTPases, has been identified to play a key role in the dynamic modulation of E-cadherin and N-cadherin expression at the cell surface (10, 12). Rab GTPases mediate the spatial and temporal recruitment of effector proteins to distinct cellular compartments through conformational changes in the protein. Active Rab bound to GTP (Rab GTP) subsequently binds to the endosome and directs endocytic transport, via specific interactions with multiple Rab effector proteins. Hydrolysis of Rab GTP into the inactive, GDP-bound form results in dissociation of Rab from the endosome (13). Endosomes are recycled by sorting into the Rab4-positive early endosome, which promotes rapid recycling to the cell surface (14, 15). Cargo destined for degradation is delivered via Rab7-dependent transport of late endosomes to lysosomes, whereas Rab9 indirectly shuttles cargo to the late endosome via sorting within the trans-Golgi network (16, 17). Cadherin trafficking through these Rab GTPases has been previously studied in tumor cell lines; Rab7 regulates lysosomal degradation of E-cadherin, whereas Rab4 effector protein, N-Myc down-regulated gene 1, enhances recycling of E-cadherin to the epithelial cell surface (16, 18). Rab4, -7, and -9 are expressed in endothelial cells (19); however, their function in this cell type has not been well established. Furthermore, the role that Rab GTPases play in the pulmonary endothelium has not been previously studied.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that Rab GTPases regulate pulmonary endothelial barrier integrity through modulation of VE-cadherin trafficking to the AJ. We aimed to investigate the role of prorecycling Rab4 and prodegradative Rab7 and -9 on the pulmonary endothelium. Our studies demonstrate enhanced barrier function in baseline conditions after overexpression of constitutively active, endosome-bound Rab4 (Rab4Q67L). We further observe attenuation of LPS-induced barrier disruption in vitro after overexpression of wild-type Rab4 (Rab4wt), constitutively active form of Rab4 (Rab4Q67L), or dominant-negative form of Rab9 (Rab9S21N). These findings were mirrored in vivo using Pseudomonas aereginosa–induced pulmonary edema formation. Internalization of VE-cadherin, after LPS exposure, was attenuated in endothelial cells overexpressing Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L, and Rab9S21N. Inhibition of Rab7 (Rab7T22N) exerted no effect on endothelial monolayer resistance, pulmonary edema formation, or changes in VE-cadherin expression at the endothelial cell surface. Our studies demonstrate that activation of prorecycling Rab4 or inhibition of prodegradative Rab9 enhances pulmonary endothelial barrier function through regulation of VE-cadherin expression at the cell surface. We propose that targeted modulation of endocytic proteins may offer novel therapeutic value for endothelium disruption in patients with ARDS.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

All materials were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise stated. Rat lung microvascular endothelial cells (LMVECs; Vec Technologies, Rensselaer, NY) were maintained in MCDB-131 (Vec Technologies) and used between passages 3 and 11.

LPS (endotoxin) from Escherichia coli serotype 0111:B4 was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA103 was a kind gift from Dr. Troy Stevens (University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL).

The vectors encoding wild-type (Rab4WT), dominant-positive (Rab4Q67L), and dominant-negative (Rab4S22N) Rab4 were a kind gift from Mary McCaffrey (Cell and Molecular Biology, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland) (20). The vectors encoding dominant-negative Rab7 (Rab7T22N) and Rab9 (Rab9S21N) were purchased from Addgene (plasmid nos. 12660 and 12664). Phosphorylated green fluorescent protein (GFP)-C1 was obtained from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). Antibodies directed against VE-cadherin, early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), lysosomal associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), Rab4, and actin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies directed against Rab7 and Rab9 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

Liposome Preparation

Dimethyldioctadecyl-ammonium bromide and cholesterol were mixed in chloroform to produce liposomes, as described elsewhere (11, 21). Liposomes were combined with cDNA (50 μg) and injected into the retrobulbar sinus of the orbit of 8- to 10-week-old anesthetized C57 BL/6 male mice. cDNA was overexpressed for 48 hours before the experiment end-point.

In Vivo Models of ARDS

Live P. aeruginosa (PA103) bacteria, or PBS vehicle, was administered via a single intratracheal injection (107 CFU). At 4 hours after PA103 administration, lungs were removed from mice, lightly blotted, and wet weight was recorded immediately. Lungs were then dried for 72 hours at 90°C and dry weight was recorded. Data are presented as the ratio of wet-to-dry lung weight (22). All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Brown University, and comply with the Health Research Extension Act and U.S. Public Health Service policy.

Whole Cell Indirect ELISA

Cell surface levels of VE-cadherin were measured on transfected LMVECs treated in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/ml) by whole-cell ELISA as previously described (11).

Endothelial Monolayer Resistance Measurements

Changes in endothelial monolayer permeability were assessed by measuring endothelial resistance using the electrical cell impedance sensor (ECIS) technique (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY), as previously described (11, 21). After a baseline read period, monolayers were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml), and resistance was measured over time. cDNA overexpression was confirmed at 48 hours after transfection via immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblotting

LMVECs were transiently transfected with cDNA encoding Rab4 mutants or GFP, using PolyJet reagent and treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) or vehicle for 6 hours. Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer and 50 μg cell lysate was resuspended in Laemmli buffer and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Immunofluorescence Studies

LMVECs were seeded onto collagen-coated glass coverslips to confluence, followed by exposure to LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 hours. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked in 5% donkey serum, followed by incubation in primary antibody, the appropriate fluorescently tagged secondary antibody before coverslips were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and images were captured. Colocalization quantification was performed using Zen 2011 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

For three or more groups, differences among the means were tested for significance in all experiments by ANOVA with Fisher’s least significance difference test. Significance was reached when the P value was less than 0.05. Values presented are means (±SD).

Results

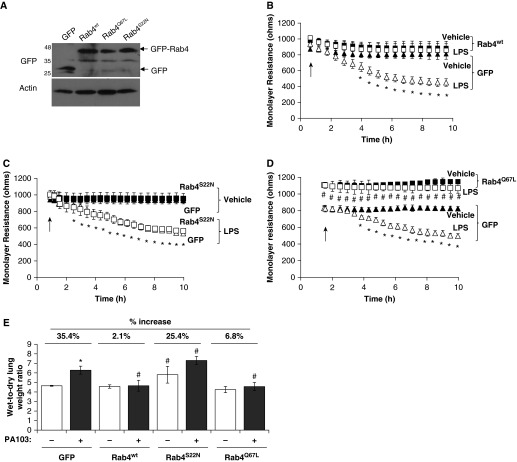

Rab4 Activation Enhances Endothelial Barrier Integrity and Attenuates Bacteria- and Endotoxin-Induced Barrier Disruption In Vitro and In Vivo

Our previous studies demonstrate a role for the endocytic adaptor protein, p18, on pulmonary endothelial barrier function. We first sought to assess whether monolayer integrity of LMVECs was regulated by overexpression of wild-type, constitutively active, or constitutively inactive mutants of the prorecycling Rab GTPase, Rab4. Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with cDNA encoding GFP-conjugated Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L or Rab4S22N. Overexpression of cDNA was confirmed by immunoblot analysis for GFP protein (Figure 1A). Densitometry analysis (measured in relative units [r.u.]) showed that equivalent levels of GFP were expressed in LMVECs transiently transfected with GFP (1.01 ± 0.26 r.u.), Rab4wt (1.01 ± 0.24 r.u.), Rab4Q67L (1.06 ± 0.07 r.u.), or Rab4S22N (1.19 ± 0.18 r.u.). The percentage of GFP-positive cells compared with total adherent cells was not significantly different for LMVECs transiently transfected with GFP (51.4 ± 13%), Rab4wt (53.3 ± 4%), Rab4Q67L (48.3 ± 11.3%), or Rab4S22N (55.2 ± 9.1%). Endothelial monolayer resistance of LMVECs overexpressing Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L, or Rab4S22N was assessed by ECIS studies. After a baseline reading, cells were exposed to LPS (1 μg/ml) and resistance was measured over 10 hours to assess barrier function. Endothelial monolayer resistance of LMVECs overexpressing Rab4Q67L, but not Rab4wt or Rab4S22N, was significantly increased compared with barrier resistance of GFP-overexpressing cells (Figures 1B–1D). We noted that overexpression of any of the Rab4 mutant proteins in LMVECs exhibited no significant effect on cell viability, as measured by reduction of soluble yellow tetrazolium dye into insoluble purple formazan using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (data not shown). To further assess the role of Rab4 activity on endothelial barrier integrity, we measured the monolayer resistance of LMVECs overexpressing Rab4 mutant protein in the presence of the barrier-disruptive agent, LPS. As previously reported (11), we observed a significant increase in barrier permeability after LPS exposure in GFP-overexpressing cells (Figures 1B–1D). Interestingly, overexpression of both wild-type (Rab4wt) and constitutively active (Rab4Q67L) Rab4 significantly attenuated LPS-induced permeability of the endothelial monolayer (Figures 1B and 1D). To determine if these in vitro findings were also observed in vivo, we next examined whether overexpression of Rab4 mutants within the intact lung was associated with changes in bacteria-induced pulmonary edema formation. Cationic liposomes encapsulating cDNA encoding Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L, Rab4S22N, or GFP were injected into the retro-orbital vein of C57/BL6 mice. Previous studies with cationic liposomes demonstrate that overexpression is observed at 48 hours after injection of cDNA for proteins of varying molecular weight from 27 to 78 kD; however, it is likely that protein overexpression occurs throughout the lung, and not specifically in endothelial cells (11, 21, 23, 24). At 44 hours after liposome injection, mice were exposed to the live bacteria, P. aeruginosa strain PA103, via intratracheal injection, for a further 4 hours and pulmonary edema formation was assessed by lung wet-to-dry ratio. Mice overexpressing dominant-negative Rab4 (Rab4S22N) display significant increase in lung edema formation at both baseline conditions and after exposure to PA103 compared with GFP overexpression (Figure 1E). Similar to our in vitro findings, overexpression of both wild-type (Rab4wt) and constitutively active (Rab4Q67L) Rab4 in the pulmonary vasculature significantly attenuated PA103-induced lung edema formation (Figure 1E). Our data demonstrate that Rab4 activity regulates the pulmonary endothelial barrier integrity. We further show that activation of Rab4 protects the pulmonary endothelium against endotoxin- and bacteria-induced pulmonary vascular leak in vitro and in vivo, respectively.

Figure 1.

Constitutive activation of Rab4 enhances endothelial barrier function and attenuates LPS- or Pseudomonas aeruginosa–induced permeability in vitro and in vivo. (A–D) Equivalent numbers of lung microvascular endothelial cells (LMVECs) were transiently transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP; triangles) or Rab4wt (B), Rab4Q67L (C) or Rab4S22N (D) cDNA (squares). After 48 hours, changes in endothelial monolayer resistance were measured, in the presence (open symbols) and absence (solid symbols) of LPS (1 μg/ml). Overexpression was assessed by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates using antibodies directed against GFP, with a loading control of actin (A). (E) Adult (8–10 wk) C57/BL6 male mice were injected with liposomes containing cDNA encoding GFP, Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L, or Rab4S22N. At 44 hours after injection, mice were injected with P. aeruginosa PA103 (107 CFU, intratracheally) for a further 4 hours, and lung weights were measured before and after a 72-hour drying period. Arrows indicate addition of LPS. Data are presented as mean (±SD); n = 4–5; *P < 0.05 versus vehicle, #P < 0.05 versus GFP with respective treatment.

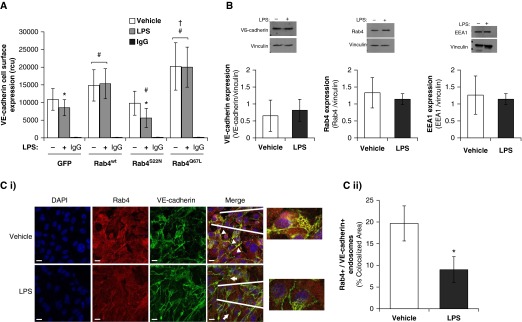

Rab4 Regulates LPS-Induced Internalization of VE-Cadherin

To understand how Rab4 activity regulates pulmonary endothelial barrier integrity in vitro and in vivo, we next assessed the effect of Rab4 mutant proteins on VE-cadherin protein expression at the endothelial cell surface. A significant increase in VE-cadherin expression at the cell surface was observed in LMVECs overexpressing both Rab4wt and Rab4Q67L (Figure 2A). As previously demonstrated (11), after exposure to LPS, VE-cadherin expression at the cell surface was significantly decreased in GFP-overexpressing LMVECs (Figure 2A). Overexpression of both Rab4wt and Rab4Q67L in LMVECs attenuated the effect of LPS on VE-cadherin surface expression (Figure 2A). Despite no change in endothelial monolayer resistance (Figure 1C), overexpression of RabS22N significantly reduced VE-cadherin levels at the cell surface compared with GFP-overexpressing LMVECs after exposure to LPS (Figure 2A). The whole-cell expression levels of VE-cadherin in LMVECs after LPS exposure was not significantly changed (Figure 2B), indicating that LPS regulates the localization, but not synthesis or degradation of VE-cadherin. Likewise, LMVEC expression levels of Rab4 and EEA1, indicative of early endosome quantity, were also unaffected by treatment with LPS (Figure 2B). Therefore, to understand how Rab4 may affect VE-cadherin cell surface levels, we next assessed and quantified the colocalization of Rab4 with VE-cadherin after LPS exposure using immunofluorescence studies. At baseline conditions, Rab4 colocalized with VE-cadherin at regions of the cell surface (Figure 2C [i]). After exposure to LPS, colocalization was significantly reduced with Rab4 exhibiting a dispersed localization (Figure 2C [i]). Zeiss image analysis showed that there was a significant decrease in the VE-cadherin–Rab4 colocalization (Figure 2C [ii]). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Rab4 activation regulates VE-cadherin localization at the endothelial cell surface and attenuates VE-cadherin internalization.

Figure 2.

Rab4 localizes to cell surface vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, and Rab4 activation attenuates LPS-induced internalization of VE-cadherin from the cell surface. (A and B) Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with GFP or Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L, or Rab4S22N cDNA. At 48 hours, cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 hours. (A) Cell surface expression of VE-cadherin was determined with whole-cell indirect ELISA using chemiluminescence. Nonspecific binding was assayed using IgG (rcu, relative chemiluminescence units). (B) Expression of VE-cadherin, Rab4 and early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) was measured in whole cell lysates by immunoblot analysis. Blots were stripped and reprobed for vinculin as loading control, and densitometry analysis was performed. (C) LMVECs were grown to confluence on gelatin-coated glass coverslips and treated with vehicle (saline) or LPS (1 μg/ml, 6 h). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and immunofluorescently stained for Rab4 and VE-cadherin, followed by Texas red– and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled secondary antibodies, respectively. Images were captured via microscopy at 100× magnification. Nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Scale bars, 20 μm. Arrowheads indicate areas of colocalization, and arrows indicate areas of VE-cadherin internalization from cell surface. Representative images are presented (i). Colocalization of VE-cadherin with Rab4 was quantified using Image J colocalization software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (ii). Data are presented as mean (±SD); n = 3 (B and C) and 6 (A). *P < 0.05 versus vehicle, #P < 0.05 versus GFP, †P < 0.05 versus Rab4wt.

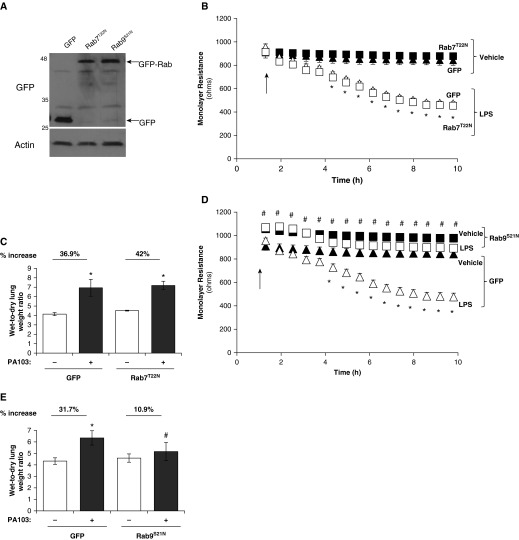

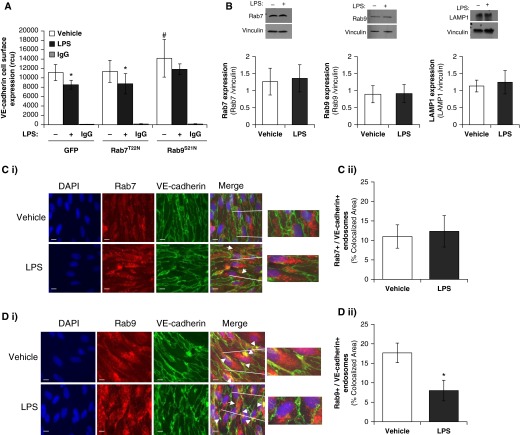

Inhibition of Rab9, but Not Rab7, Attenuates LPS-Induced VE-Cadherin Internalization and Pulmonary Endothelial Barrier Disruption

Although Rab4 is vital in the recycling of the early endosome, there are other Rab GTPases, Rab7 and Rab9, which regulate the endosome degradative pathway. We next sought to assess whether barrier integrity was regulated by Rab4-mediated prorecycling of VE-cadherin or reduced degradation of VE-cadherin through inhibition of Rab7 and Rab9 GTPases. Monolayer integrity of LMVECs was regulated by overexpression of inactive mutants of the prodegradative Rab GTPase, Rab7 (Rab7T22N) and Rab9 (Rab9S21N). Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with cDNA encoding GFP-conjugated Rab7T22N and Rab9S21N. Overexpression of cDNA was confirmed by immunoblot analysis for GFP protein (Figure 3A). Densitometry analysis showed that equivalent levels of GFP were expressed in LMVECs transiently transfected with GFP (1.30 ± 0.19 r.u.), Rab7T22N (1.09 ± 0.25 r.u.), or Rab9S21N (1.14 ± 0.16 r.u.). Baseline endothelial monolayer resistance of LMVECs overexpressing Rab9S21N, but not Rab7T22N, was significantly increased compared with barrier resistance of GFP-overexpressing cells (Figures 3B and 3D). Likewise, overexpression of Rab9S21N, but not Rab7T22N, significantly attenuated LPS-induced decrease in monolayer resistance observed in LMVECs overexpressing GFP (Figures 3B and 3D). Overexpression of either Rab7T22N or Rab9S21N in LMVECs exhibited no significant effect on cell viability, as measured by MTT assay (data not shown). To determine if these in vitro findings were also observed in vivo, we examined whether overexpression of Rab7T22N and Rab9S21N cDNA within the intact lung was associated with changes in bacteria-induced pulmonary edema formation. Similar to our in vitro findings, overexpression of Rab9S21N in the pulmonary vasculature significantly attenuated PA103-induced lung edema formation, whereas Rab7T22N had no effect on wet-to-dry lung weight ratio (Figures 3C and 3E). We further assessed the role of Rab7T22N and Rab9S21N on the pulmonary endothelium by studying VE-cadherin expression at the endothelial cell surface. A significant decrease in VE-cadherin levels at the plasma membrane was noted after LPS exposure in LMVECs overexpressing GFP and Rab7T22N (Figure 4A). Interestingly, overexpression of Rab9S21N increased VE-cadherin expression at the cell surface under baseline conditions; however, LPS-induced internalization of VE-cadherin was similar to GFP- and Rab7T22N-overexpressing endothelial cells (Figure 4A). Similar to markers of the early endosome (Figure 2B), whole-cell expression of the late endosome proteins, Rab7, Rab9, and LAMP1, was not affected by exposure to LPS (Figure 4B). Furthermore, colocalization of VE-cadherin with Rab9, but not Rab7, was observed at the cell surface and significantly attenuated after exposure to LPS (Figures 4C and 4D).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of pro-lysosomal Rab GTPase Rab9, but not Rab7, enhances endothelial barrier function and attenuates LPS- or P. aeruginosa–induced permeability in vitro and in vivo. (A, B, and D) Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with GFP (triangles), Rab7T22N (B), or Rab9S21N (D) cDNA (squares). After 48 hours, changes in endothelial monolayer resistance were measured using electrical cell impedance sensor (ECIS) in the presence (open symbols) and absence (solid symbols) of LPS (1 μg/ml). Overexpression was assessed by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates using antibodies directed against GFP, with a loading control of actin (A). (C and E) Adult (8–10 wk old) C57/BL6 male mice were injected with liposomes containing cDNA encoding GFP, Rab7T22N, or Rab9S21N. At 44 hours after injection, mice were injected with P. aeruginosa PA103 (107 CFU, intratracheally) for a further 4 hours, and lung weights were measured before and after a 72-hour drying period. Arrows indicate addition of LPS. Data are presented as mean (±SD); n = 4–5; *P < 0.05 versus vehicle, #P < 0.05 versus GFP.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of prolysosomal Rab GTPase Rab9, but not Rab7, increases VE-cadherin expression at the cell surface. (A) Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with GFP, Rab7T22N, or Rab9S21N cDNA. At 48 hours, cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 hours. Cell surface expression of VE-cadherin was determined with whole-cell indirect ELISA using chemiluminescence. Nonspecific binding was assayed using IgG. (B) Expression of Rab7, Rab9, and lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) was measured in whole-cell lysates from LMVECs exposed to LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 hours by immunoblot analysis. Blots were stripped and reprobed for vinculin as loading control, and densitometry analysis was performed. (C and D) LMVECs were grown to confluence on gelatin-coated glass coverslips and treated with vehicle (saline) or LPS (1 μg/ml, 6 h). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and immunofluorescently stained for Rab7 (C) or Rab9 (D) and VE-cadherin, followed by Texas red– and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies, respectively. Images were captured via microscopy at 100× magnification. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bars, 20 μm. Arrowheads indicate areas of colocalization, and arrows indicate areas of VE-cadherin internalization from cell surface. Representative images are presented (i). Colocalization of VE-cadherin with Rab7 or Rab9 was quantified using Image J cololcalization software (ii). Data are presented as mean (±SD); n = 3 (B, C, and D) and 6 (A). *P < 0.05 versus vehicle, #P < 0.05 versus GFP.

Our data demonstrate that reduced trafficking to the late endosome pathway, through inhibition of Rab9, attenuates VE-cadherin internalization from the AJ and pulmonary endothelial barrier disruption in vitro and in vivo. We show that reduced trafficking from late endosome to lysosome, through inhibition of Rab7, has no effect on endothelial monolayer integrity. Thus, the pulmonary endothelial barrier is regulated by the prodegradative Rab9 and prorecycling Rab4 GTPases.

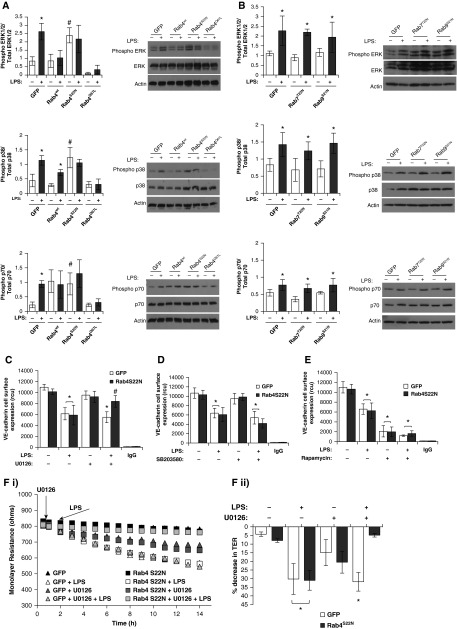

Rab4 Regulates Endothelial Barrier Integrity through an Extracellular Signal–Regulated Kinase–Dependent Pathway

Finally, we sought to understand the mechanism through which Rab4 and Rab9 regulate endothelial barrier function. Rab GTPases have been shown to regulate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways (25–27). We have previously demonstrated that the endocytic adaptor protein, p18, regulates MAPK and p70 (part of mTOR signaling pathway) phosphorylation (11). Thus, we next assessed the effect of Rab4, Rab7, and Rab9 activity on p38, extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), and p70 phosphorylation in the presence and absence of LPS. Under baseline conditions, phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and p70 was significantly increased in LMVECs overexpressing dominant-negative Rab4 (Rab4S22N), but not constitutively active Rab4 (Rab4Q67L), compared with GFP-overexpressing cells (Figure 5A). As previously demonstrated, LPS exposure significantly increased phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and p70 in LMVECs overexpressing GFP (Figure 5A) (11). Interestingly, exposure to LPS did not exert any effect on the phosphorylation of ERK or p70 in LMVECs transiently transfected with any of the Rab4 cDNAs (Figure 5A). Although LPS treatment had no effect on p38 phosphorylation in LMVECs overexpressing Rab4S22N and Rab4Q67L, there was a significant increase in LPS-induced phosphorylation in Rab4wtoverexpressing cells (Figure 5A). In LMVECs overexpressing Rab7T22N or Rab9S21N, phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and p70 was unaffected in both the presence and absence of LPS (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Protection from LPS-induced endothelial permeability, mediated by Rab4 activity, is dependent on extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation. (A and B) Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with GFP, Rab4wt, Rab4Q67L, or Rab4S22N cDNA (A) or GFP, Rab7T22N, or Rab9S21N cDNA (B). At 48 hours, cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 hours. Phosphorylation of p38, ERK1/2, or p70 was assessed in whole-cell lysates by immunoblot analysis with an antibody specific to each phosphorylated protein. Blots were stripped and reprobed for total protein expression and vinculin as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. (C–F) Equivalent numbers of LMVECs were transiently transfected with GFP or Rab4S22N cDNA. At 48 hours, cells were pretreated with chemical inhibitors, U0126 (DMSO vehicle, 10 μM) (C), SB203580 (DMSO vehicle, 10 nM) (D), or rapamycin (DMSO vehicle, 10 nM) (E) for 30 minutes followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6 hours. Cell surface expression of VE-cadherin was determined with whole-cell indirect ELISA using chemiluminescence. Nonspecific binding was assayed using IgG. Changes in endothelial monolayer resistance were measured using ECIS (F [i]), and percentage drop in monolayer resistance was calculated (F [ii]). Data are presented as mean (±SD); n = 3 (A, B, and F) and 4 (C–E). *P < 0.05 versus GFP, #P < 0.05 versus vehicle.

The next studies sought to understand whether ERK, p38, and p70 phosphorylation, induced by Rab4S22N overexpression, play a role in VE-cadherin expression at the cell surface. LMVECs overexpressing Rab4S22N were exposed to LPS in the presence and absence of the chemical inhibitors for ERK (U0126), p38 (SB203580), or rapamycin (mTOR/p70) (Figures 5C–5E). As previously demonstrated (11), GFP-overexpressing cells exposed to rapamycin, but not U0126 and SB203580, displayed a significant decrease in VE-cadherin levels at the cell surface (Figures 5C–5E). In the presence of SB203580 and rapamycin, LPS caused a significant decrease in VE-cadherin levels at the cell surface in LMVECs expressing either GFP or Rab4S22N (Figures 5D and 5E). Interestingly, LPS-induced internalization of VE-cadherin was attenuated by U0126 in cells overexpressing Rab4S22N compared with GFP (Figure 5C). These findings were also observed in studies measuring endothelial monolayer resistance (Figure 5F). Our data demonstrate that Rab4, but not Rab9, mediates LPS-induced endothelial barrier disruption through an ERK-dependent mechanism.

Taken together, our data show that activation of Rab4 and inhibition of Rab9 GTPases attenuate LPS-induced endothelial barrier disruption in vitro and in vivo through modulation of VE-cadherin expression levels at the endothelial cell surface. We further demonstrate that Rab4, but not Rab9, regulates the pulmonary endothelium through an ERK-dependent, but not p38- or p70-dependent, pathway. We propose that regulation of select Rab GTPase activities may represent novel therapeutic targets in the treatment of vascular permeability in patients with ARDS.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate a significant role for Rab4 and Rab9, but not Rab7, GTPase in regulating the pulmonary endothelium in settings of ARDS. Our studies indicate that activation of Rab4 and inhibition of Rab9 increase VE-cadherin levels at the endothelial cell surface and improve endothelial barrier function in vitro and in vivo after exposure to LPS and Pseudomonas, respectively. We further show that LPS-induced barrier disruption occurs concomitant with reduced colocalization of VE-cadherin with Rab4 and Rab9. Finally, our studies demonstrate that Rab4, but not Rab7 or Rab9, regulates VE-cadherin surface expression and endothelial monolayer resistance through attenuating LPS-induced ERK activation. We thus propose that Rab4 activation represents a novel therapeutic target in the treatment of pulmonary edema in ARDS.

The link between endothelial permeability and endosomal trafficking of VE-cadherin has been previously established (11, 28). Our previous studies demonstrate that the endosome adaptor protein, p18, enhances endothelial barrier function in vitro and in vivo through association with the early endosome and increased VE-cadherin expression at the endothelial cell surface (11). Endosomal trafficking of VE-cadherin away from the plasma membrane is therefore an important target in regulating vascular permeability. Our present research indicates that Rab4 activation and Rab9 inhibition enhances endothelial barrier function through increased VE-cadherin recycling to the cell surface. These two Rab GTPases have opposing roles in endocytic trafficking; Rab4 is responsible for rapid recycling of the early endosome to the cell surface, and Rab9 mediates traffic from the sorting endosome to the late endosome for lysosomal degradation (14, 17). Both the molecular activation of Rab4 and inhibition of Rab9, by overexpressing the GTP- and GDP-bound mutants, respectively, could therefore be expected to have the same effect on cellular response. Indeed, our studies demonstrate that Rab9 inhibition enhances VE-cadherin expression levels at the cell surface and endothelial barrier integrity, under baseline conditions, to the same degree as Rab4 activation. However, our studies also show that inhibition of Rab7, the Rab GTPase responsible for late endosome trafficking to the lysosome for degradation, has no effect on endothelial barrier function. It is possible that inhibition of Rab9 results in the accumulation of VE-cadherin in sorting endosomes, which cannot be trafficked to the late endosome for degradation, and therefore are shuttled back into the recycling pathway, increasing the pool of the cadherin protein to be expressed at the cell surface. Conversely, Bastin and Heximer (29) have shown that inhibition of Rab7 results in the accumulation of cargo in late endosomes, which do not fuse with the lysosome and cannot revert to the recycling pathway. Therefore, dominant-negative Rab7 causes levels of VE-cadherin trafficked from the cell surface to be unchanged, but VE-cadherin accumulated in the late endosome after LPS exposure to increase. Similarly, Rab4 inhibition results in the accumulation of cargo in early endosomes, which cannot be recycled or trafficked to the late endosome, resulting in reduced recycling of VE-cadherin to the cell surface after LPS-induced breakdown of the endothelium (30). The studies presented here are the first to study the physiological effect of these Rab GTPases on VE-cadherin levels at the cell surface and demonstrate that tightly coordinated regulation of trafficking pathways is needed to maintain an intact pulmonary endothelium.

The studies presented here demonstrate a role for active Rab4Q67L, but not Rab4wt, on endothelial barrier function under baseline conditions; Rab4wt becomes barrier protective after exposure to LPS. Endocytic trafficking in the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 pathway, the key signaling pathway through which LPS exhibits an effect on cells, has recently emerged as a key feature of TLR4 function. After LPS stimulation, TLR4 initiates a myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)-mediated signaling pathway at the plasma membrane accompanied by internalization of the LPS–TLR4 complex into the Rab4-positive early endosome (31). In this position, the second signaling pathway is triggered through Toll interleukin receptor domain containing adapter including interferon β (TRIF) and TRIF-related adaptor molecule; therefore, LPS-induced endocytosis of TLR4 is essential for its signaling function (31). Interestingly, Rab GTPases regulate TLR4 trafficking; for example, Rab7 negatively regulates TLR4 trafficking to late endosomes for degradation (32). Although the role of Rab4 on TLR4 is unclear, it is possible that LPS-dependent internalization of TLR4 activates the early endosome signaling network and up-regulates Rab4 activity. Thus, we can speculate that, in settings of LPS exposure, Rab4 becomes active, binds to the endosome, and promotes endothelial barrier function in a manner similar to Rab4Q67L. Further studies are necessary to understand the role of Rab4 activity on TLR4 trafficking and, conversely, the role of TLR4 signaling on Rab4 activity.

Endosome trafficking is tightly regulated by the Rab GTPase family, which cycles between an active, GTP-bound and an inactive, GDP-bound form. Due to their low GTP hydrolysis rate, specific GTPase-activating proteins are required for efficient and fast GTP hydrolysis. GTPase-activating proteins complement the active site of the Rab and increase the intrinsic hydrolysis rate by several orders of magnitude. Moreover, reversible attachment of Rabs to membranes requires prenylation of C-terminal cysteines, which depends on Rab geranylgeranyltransferase and Rab escort protein (REP) (13). In the cytosol, prenylated Rabs are bound to the chaperone GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI), which is similar in sequence and structure to REP (33–35). REP and GDI interact with the switch regions, C-terminal residues, and the prenyl anchor of the Rab, and both show preference for the GDP-bound form (34, 36, 37). Thus, multiple effector and adaptor proteins are vital in the regulation of Rab GTPase activation and localization (38). Interestingly, the endosome adaptor protein, p18, colocalizes with Rab4 at the early endosome and Rab7 at the late endosome; in the latter association, p18 regulates lysosome formation and trafficking (39). Our previous studies demonstrate a role for p18 in increased recycling of VE-cadherin to the endothelial cell surface to enhance pulmonary endothelial barrier function (11). It is therefore possible that p18 acts as a regulator of Rab GTPases, to mediate trafficking of VE-cadherin, in a manner similar to our present studies with Rab4 and Rab9. Indeed Takahashi and colleagues (40) demonstrated that p18-deficient cells displayed increased expression of Rab7; however, the group did not study Rab4 or Rab9 in these cells. Furthermore, although the sequence for p18 contains putative sites for myristoylation and palmitoylation, allowing association with the endosome membrane, it does not show any homology with known Rab GEFs, REPs, or GDIs (39, 41, 42). Further studies are therefore needed to evaluate the role of p18 in Rab4- and Rab9-dependent mediated regulation of the pulmonary endothelium.

Although trafficking is the key role for endosomes, emerging data suggest that complexes formed on the endosome membrane dictate important signaling events for the cell. One such example is the formation of the mTOR complex at the late endosome, mediated by p18 and other Ragulator proteins, which regulates mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways (39, 43). Indeed, our previous studies also demonstrated that p18 regulates mTOR, p38, and MAPK kinase (MEK) phosphorylation (11). Furthermore, chemical inhibition of these proteins can increase barrier permeability; however, the effect of p18 on the pulmonary endothelium was demonstrated to be independent of its role on MEK, p38, and mTOR activity (11). Similarly, Rab GTPases have been linked with mTOR and MAPK localization and signaling. Specific targeting of early to late endosome trafficking, using GDP-locked Rab5 mutants, results in aberrant localization and inhibition of mTOR (25, 27, 44). Both Rab7 and Rab11 have been observed to regulate p38 and ERK activation in macrophages and Drosophila, respectively (45–47). Interestingly, Wang and colleagues noted (48) that Rabin8, a GEF for Rab8, is serine phosphorylated by ERK in response to EGF exposure, which significantly increases the GEF activity of Rabin8. Studies presented here demonstrate that Rab4, but not Rab7 or Rab11, affects p38, ERK, and p70 (part of the mTOR pathway) phosphorylation in pulmonary endothelial cells, with the activation of Rab4 attenuating LPS-induced phosphorylation of these proteins. Similar to LPS exposure, inhibition of Rab4 enhances phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and p70. Interestingly, the disruptive effect of LPS and dominant-negative Rab4 on the pulmonary endothelium was attenuated by inhibition of ERK, but not p38 and mTOR. We conclude that Rab4 regulates the pulmonary endothelium, in settings of LPS-induced disruption, through maintaining low levels of ERK phosphorylation in the cell. The effect of ERK inhibition on different Rab-dependent pathways has been previously demonstrated in tumor progression and development, although the precise mechanisms for this are unclear (45, 49, 50). Our studies indicate that Rab4 activation reduces LPS-induced ERK phosphorylation in microvascular endothelial cells. Thus, it is possible that Rab4 and ERK are phosphorylated in a feedback loop, depending on the stimulus used and the cell type assessed, to regulate trafficking of cargo, such as cadherins, to and from the cell surface.

The link between endothelial permeability in vitro and in vivo with VE-cadherin at the AJ is well established; AJ disruption is the key contributor of vascular permeability (51–54). Our previous studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between increased VE-cadherin expression levels at the cell surface, enhanced catenin–cadherin interactions, elevated endothelial barrier resistance, and protective in vivo pulmonary endothelium integrity, as assessed by reduced pulmonary edema formation (11). Interestingly, under baseline conditions, our present study with Rab GTPases does not show this same correlation. For example, overexpression of wild-type Rab4 has no effect on endothelial barrier integrity in vitro or in vivo at baseline, but increases cell surface expression of VE-cadherin, whereas inactivation of Rab4 has no effect on in vitro endothelial monolayer resistance, but increases baseline pulmonary edema formation in vivo. Furthermore, activation of Rab4 and inhibition of Rab9 both enhance endothelial monolayer resistance and cell surface expression of VE-cadherin, but exhibit no effect on pulmonary edema formation in vivo. These discrepancies may relate to the varied endothelial cell mechanisms that are regulated by endosomal trafficking. For example, Rab4 regulates membrane trafficking of αvβ3 integrins, which protect against LPS-induced vascular leak (46, 55–57). LPS-induced internalization of VE-cadherin, after inhibition of Rab9, represents an interesting phenomenon. Under baseline conditions, Rab9 inhibition increases VE-cadherin levels at the cell surface. Although LPS reduced the colocalization of VE-cadherin with Rab9-positive endosomes, VE-cadherin is likely to remain in the early endosome in these settings. These studies present the multifactorial nature of endosomes in the trafficking of VE-cadherin. Importantly, in response to LPS or Pseudomonas exposure, in vitro barrier disruption and in vivo pulmonary edema formation were attenuated by overexpression of wild-type Rab4, activation of Rab4, and inhibition of Rab9. Thus, select Rab GTPases can be activated or inhibited in response to physiological stress, such as bacterial infection, to protect the pulmonary endothelium from breakdown and prevent vascular permeability.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This article is the result of work supported by resources and the use of facilities at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Providence, RI). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL067795, American Heart Association grant 10GRNT4160055, Center of Biomedical Research Excellence National Institute of General Medical Sciences award 5P20 GM103652, and University Medicine Foundation of Rhode Island Hospital grant (E.O.H.); H.C. was supported by American Heart Association grant 13POST16860031.

Author Contributions: H.C. and E.O.H. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the manuscript; H.C., J.B., and H.D. designed the study, performed the experiments, and analyzed all data; G.B. contributed significantly to Figure 3; all authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0286OC on November 9, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Matthay MA, Zemans RL. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:147–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigham KL, Meyrick B. Endotoxin and lung injury. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:913–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens T, Garcia JG, Shasby DM, Bhattacharya J, Malik AB. Mechanisms regulating endothelial cell barrier function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L419–L422. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.3.L419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anastasiadis PZ, Reynolds AB. The p120 catenin family: complex roles in adhesion, signaling and cancer. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1319–1334. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.8.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corada M, Mariotti M, Thurston G, Smith K, Kunkel R, Brockhaus M, Lampugnani MG, Martin-Padura I, Stoppacciaro A, Ruco L, et al. Vascular endothelial-cadherin is an important determinant of microvascular integrity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9815–9820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broermann A, Winderlich M, Block H, Frye M, Rossaint J, Zarbock A, Cagna G, Linnepe R, Schulte D, Nottebaum AF, et al. Dissociation of VE-PTP from VE-cadherin is required for leukocyte extravasation and for VEGF-induced vascular permeability in vivo. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2393–2401. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulte D, Küppers V, Dartsch N, Broermann A, Li H, Zarbock A, Kamenyeva O, Kiefer F, Khandoga A, Massberg S, et al. Stabilizing the VE-cadherin–catenin complex blocks leukocyte extravasation and vascular permeability. EMBO J. 2011;30:4157–4170. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gavard J, Gutkind JS. VEGF controls endothelial-cell permeability by promoting the β-arrestin–dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1223–1234. doi: 10.1038/ncb1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le TL, Yap AS, Stow JL. Recycling of E-cadherin: a potential mechanism for regulating cadherin dynamics. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:219–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chichger H, Duong H, Braza J, Harrington EO. p18, a novel adaptor protein, regulates pulmonary endothelial barrier function via enhanced endocytic recycling of VE-cadherin. FASEB J. 2015;29:868–881. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-257212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lock JG, Stow JL. Rab11 in recycling endosomes regulates the sorting and basolateral transport of E-cadherin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1744–1755. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer SR. Rab GTPase regulation of membrane identity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daro E, van der Sluijs P, Galli T, Mellman I. Rab4 and cellubrevin define different early endosome populations on the pathway of transferrin receptor recycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9559–9564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Der Sluijs P, Hull M, Zahraoui A, Tavitian A, Goud B, Mellman I. The small GTP-binding protein rab4 is associated with early endosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6313–6317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Y, Press B, Wandinger-Ness A. Rab 7: an important regulator of late endocytic membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1435–1452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lombardi D, Soldati T, Riederer MA, Goda Y, Zerial M, Pfeffer SR. Rab9 functions in transport between late endosomes and the trans Golgi network. EMBO J. 1993;12:677–682. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kachhap SK, Faith D, Qian DZ, Shabbeer S, Galloway NL, Pili R, Denmeade SR, DeMarzo AM, Carducci MA. The N-Myc down regulated gene1 (NDRG1) is a Rab4a effector involved in vesicular recycling of E-cadherin. PLoS One. 2007;2:e844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Leeuw HP, Koster PM, Calafat J, Janssen H, van Zonneveld AJ, van Mourik JA, Voorberg J. Small GTP-binding proteins in human endothelial cells. Br J Haematol. 1998;103:15–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCaffrey MW, Bielli A, Cantalupo G, Mora S, Roberti V, Santillo M, Drummond F, Bucci C. Rab4 affects both recycling and degradative endosomal trafficking. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chichger H, Grinnell KL, Casserly B, Chung CS, Braza J, Lomas-Neira J, Ayala A, Rounds S, Klinger JR, Harrington EO. Genetic disruption of protein kinase Cδ reduces endotoxin-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L880–L888. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klinger JR, Murray JD, Casserly B, Alvarez DF, King JA, An SS, Choudhary G, Owusu-Sarfo AN, Warburton R, Harrington EO. Rottlerin causes pulmonary edema in vivo: a possible role for PKCδ. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;103:2084–2094. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00695.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chichger H, Braza J, Duong H, Harrington EO. SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 and focal adhesion kinase protein interactions regulate pulmonary endothelium barrier function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52:695–707. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0489OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grinnell KL, Chichger H, Braza J, Duong H, Harrington EO. Protection against LPS-induced pulmonary edema through the attenuation of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B oxidation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:623–632. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0271OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flinn RJ, Yan Y, Goswami S, Parker PJ, Backer JM. The late endosome is essential for mTORC1 signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:833–841. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jopling HM, Odell AF, Hooper NM, Zachary IC, Walker JH, Ponnambalam S. Rab GTPase regulation of VEGFR2 trafficking and signaling in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1119–1124. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Kim E, Yuan H, Inoki K, Goraksha-Hicks P, Schiesher RL, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of mTORC1 by the Rab and Arf GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19705–19709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.102483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J, Sun H, Zhang J, Hu M, Wang J, Wu G, Wang G. Regulation of β-adrenergic receptor trafficking and lung microvascular endothelial cell permeability by Rab5 GTPase. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:868–878. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastin G, Heximer SP. Rab family proteins regulate the endosomal trafficking and function of RGS4. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:21836–21849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jopling HM, Odell AF, Pellet-Many C, Latham AM, Frankel P, Sivaprasadarao A, Walker JH, Zachary IC, Ponnambalam S. Endosome-to-plasma membrane recycling of VEGFR2 receptor tyrosine kinase regulates endothelial function and blood vessel formation. Cells. 2014;3:363–385. doi: 10.3390/cells3020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Chen T, Han C, He D, Liu H, An H, Cai Z, Cao X. Lysosome-associated small Rab GTPase Rab7b negatively regulates TLR4 signaling in macrophages by promoting lysosomal degradation of TLR4. Blood. 2007;110:962–971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andres DA, Seabra MC, Brown MS, Armstrong SA, Smeland TE, Cremers FP, Goldstein JL. cDNA cloning of component A of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase and demonstration of its role as a Rab escort protein. Cell. 1993;73:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rak A, Pylypenko O, Durek T, Watzke A, Kushnir S, Brunsveld L, Waldmann H, Goody RS, Alexandrov K. Structure of Rab GDP-dissociation inhibitor in complex with prenylated YPT1 GTPase. Science. 2003;302:646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.1087761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schalk I, Zeng K, Wu SK, Stura EA, Matteson J, Huang M, Tandon A, Wilson IA, Balch WE. Structure and mutational analysis of Rab GDP-dissociation inhibitor. Nature. 1996;381:42–48. doi: 10.1038/381042a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki T, Kikuchi A, Araki S, Hata Y, Isomura M, Kuroda S, Takai Y. Purification and characterization from bovine brain cytosol of a protein that inhibits the dissociation of GDP from and the subsequent binding of GTP to smg p25A, a ras p21–like GTP-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2333–2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen F, Seabra MC. Mechanism of digeranylgeranylation of Rab proteins: formation of a complex between monogeranylgeranyl-Rab and Rab escort protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3692–3698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cabrera M, Ungermann C. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) have a critical but not exclusive role in organelle localization of Rab GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:28704–28712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.488213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nada S, Hondo A, Kasai A, Koike M, Saito K, Uchiyama Y, Okada M. The novel lipid raft adaptor p18 controls endosome dynamics by anchoring the MEK-ERK pathway to late endosomes. EMBO J. 2009;28:477–489. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi Y, Nada S, Mori S, Soma-Nagae T, Oneyama C, Okada M. The late endosome/lysosome-anchored p18-mTORC1 pathway controls terminal maturation of lysosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:1151–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson RG, Jacobson K. A role for lipid shells in targeting proteins to caveolae, rafts, and other lipid domains. Science. 2002;296:1821–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.1068886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabouridis PS. Lipid rafts in T cell receptor signalling. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:49–57. doi: 10.1080/09687860500453673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator–Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bridges D, Fisher K, Zolov SN, Xiong T, Inoki K, Weisman LS, Saltiel AR. Rab5 proteins regulate activation and localization of target of rapamycin complex 1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20913–20921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhuin T, Roy JK. Rab11 regulates JNK and Raf/MAPK-ERK signalling pathways during Drosophila wing development. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:1113–1118. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones MC, Caswell PT, Moran-Jones K, Roberts M, Barry ST, Gampel A, Mellor H, Norman JC. VEGFR1 (Flt1) regulates Rab4 recycling to control fibronectin polymerization and endothelial vessel branching. Traffic. 2009;10:754–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao M, Liu X, Li D, Chen T, Cai Z, Cao X. Late endosome/lysosome–localized Rab7b suppresses TLR9-initiated proinflammatory cytokine and type I IFN production in macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;183:1751–1758. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Ren J, Wu B, Feng S, Cai G, Tuluc F, Peränen J, Guo W. Activation of Rab8 guanine nucleotide exchange factor Rabin8 by ERK1/2 in response to EGF signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:148–153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412089112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen T, Yang M, Yu Z, Tang S, Wang C, Zhu X, Guo J, Li N, Zhang W, Hou J, et al. Small GTPase RBJ mediates nuclear entrapment of MEK1/MEK2 in tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:682–696. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qi J, Zhao P, Li F, Guo Y, Cui H, Liu A, Mao H, Zhao Y, Zhang X. Down-regulation of Rab17 promotes tumourigenic properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via Erk pathway. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:4963–4971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dejana E, Bazzoni G, Lampugnani MG. Vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin: only an intercellular glue? Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:13–19. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Konstantoulaki M, Kouklis P, Malik AB. Protein kinase C modifications of VE-cadherin, p120, and β-catenin contribute to endothelial barrier dysregulation induced by thrombin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L434–L442. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00075.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, Ancellin N, Liu CH, Kluk M, Volpi M, Sha’afi RI, Hla T. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 1999;99:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynch JJ, Ferro TJ, Blumenstock FA, Brockenauer AM, Malik AB. Increased endothelial albumin permeability mediated by protein kinase C activation. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1991–1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI114663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts M, Barry S, Woods A, van der Sluijs P, Norman J. PDGF-regulated rab4-dependent recycling of αvβ3 integrin from early endosomes is necessary for cell adhesion and spreading. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Su G, Atakilit A, Li JT, Wu N, Bhattacharya M, Zhu J, Shieh JE, Li E, Chen R, Sun S, et al. Absence of integrin αvβ3 enhances vascular leak in mice by inhibiting endothelial cortical actin formation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:58–66. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1381OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White DP, Caswell PT, Norman JC. αvβ3 and α5β1 integrin recycling pathways dictate downstream Rho kinase signaling to regulate persistent cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:515–525. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]