Ventral hernia repair represents one of the most common procedures performed by plastic and reconstructive surgeons. Despite technical advances and increased understanding over the past 30 years, however, postoperative wound complications continue to account for significant morbidity and, in turn, decreased quality of life and increased health care costs. The aim of this analysis was to determine whether the application of negative pressure wound therapy to closed incisions decreases the rate of complications compared with conventional dressings.

Keywords: Abdominal wall reconstruction, Closed incision, Hernia recurrence, Negative pressure wound therapy, Seroma, Surgical site infection, Vacuum-assisted closure, Ventral hernia repair, Wound complications, Wound dehiscence

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite advances in surgical technique, ventral hernia repair (VHR) remains associated with significant postoperative wound complications.

OBJECTIVE

A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to identify whether the application of negative pressure wound therapy to closed incisions (iNPWT) following VHR reduces the risk of postoperative wound complications and hernia recurrence.

METHODS

The PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCOPUS databases were searched for studies published through October 2015. Publications that met the following criteria were included: adult patients undergoing VHR; comparison of iNPWT with conventional dressings; and documentation of wound complications and/or hernia recurrence. The methodological quality of included studies was independently assessed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies guidelines. Outcomes assessed included surgical site infection (SSI), wound dehiscence, seroma, and hernia recurrence. Meta-analysis was performed to obtain pooled ORs.

RESULTS

Five retrospective cohort studies including 477 patients undergoing VHR were included in the final analysis. The use of iNPWT decreased SSI (OR 0.33 [95% CI 0.20 to 0.55]; P<0.0001), wound dehiscence (OR 0.21 [95% CI 0.08 to 0.55]; P=0.001) and ventral hernia recurrence (OR 0.24 [95% CI 0.08 to 0.75]; P=0.01). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of seroma formation (OR 0.59 [95% CI 0.27 to 1.27]; P=0.18).

CONCLUSION

For patients undergoing VHR, current evidence suggests a decreased incidence in wound complications using incisional NPWT compared with conventional dressings.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE

Malgré les progrès des techniques chirurgicales, la réparation de la hernie ventrale (RHV) s’associe encore à des complications importantes de la plaie postopératoire.

OBJECTIF

Les chercheurs ont réalisé une analyse systématique et une méta-analyse pour déterminer si la thérapie par pression négative sur des incisions fermées (TPNiF) après la RHV réduit le risque de complications postopératoires des plaies et la récurrence des hernies.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

Les chercheurs ont exploré les bases de données PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE et SCOPUS pour trouver des études publiées jusqu’en octobre 2015. Ils ont retenu les publications qui respectaient les critères suivants : patients adultes ayant subi une RHV, comparaison de la TPNiF avec des pansements classiques et les rapports sur les complications des plaies ou la récurrence des hernies. Ils ont évalué de manière indépendante la qualité méthodologique des études retenues à l’aide des directives de l’indice méthodologique des études non aléatoires. Ils ont évalué les résultats suivants : l’infection au foyer de l’opération (IFO), la déhiscence de la plaie, le sérome et la récurrence des hernies. Ils ont effectué une méta-analyse pour obtenir les rapports de cote (RC) regroupés.

RÉSULTATS

Les chercheurs ont retenu cinq études de cohorte rétrospectives, y compris 477 patients qui avaient subi une RHV, dans l’analyse définitive. Le recours à la TPNiF réduisait l’IFO (RC 0,33 [95 % IC 0,20 à 0,55]; P<0,0001), la déhiscence de la plaie (RC 0,21 [95 % IC 0,08 à 0,55]; P=0,001) et la récurrence de la hernie ventrale (RC 0,24 [95 % IC 0,08 à 0,75]; P=0,01). Ils n’ont pas constaté de différence statistiquement significative dans l’incidence de formation de séromes (RC 0,59 [95 % IC 0,27 à 1,27]; P=0,18).

CONCLUSION

Pour les patients qui subissent une RHV, les données actuelles indiquent que l’incidence des complications des plaies est moins élevée si on utilise la TPNiF plutôt que les pansements classiques.

Ventral hernia repair (VHR) is one of the most common operations performed by plastic and reconstructive surgeons, and general surgeons. Over the past three decades, VHR has been dramatically improved with the introduction of new prosthetic material (1,2), laparoscopic methods (3) and component separation (4). However, despite these advances, wound complications continue to account for significant postoperative morbidity in patients undergoing abdominal wall reconstruction for ventral hernia (5,6). Using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) database, a recent study demonstrated a 4.9% 30-day readmission rate in 12,673 patients undergoing VHR in 2011. Deep/incisional (12.6%) and superficial (10.5%) surgical site infection (SSI) were the most common wound complications encountered in readmitted patients (7). These undesired wound complications not only alter patient quality of life, but also markedly increase health care costs.

The negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) system was first introduced by Argenta and Morykwas (8) in 1997, and has become an effective means of managing open wounds (9,10). Its success has resulted in a new ‘rung’ on the reconstructive ladder and, arguably, an extension of each pre-existing rung (11). Prophylactic NPWT has also become popular after operations with a high risk for wound complications (12). The current literature suggests the primary mechanisms of action of NPWT include the following: drawing the wound edges together; stabilization of the wound environment; decrease in wound edema and removal of wound exudate; and microdeformations of the wound surface. Secondary effects of NPWT include increased angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation and a decrease in bacterial bioburden (13).

Recent clinical studies suggest that application of NPWT to closed incisions (iNPWT) in patients undergoing abdominal wall reconstruction/repair for ventral hernia may reduce postoperative wound complications (14–18). The purpose of the present study was to answer the following question: in patients undergoing VHR, does the application of NPWT to closed incisions, compared with conventional dressings, reduce the incidence of wound complications (SSI, seroma, wound dehiscence) or hernia recurrence? We hypothesized that iNPWT would decrease the rate of wound complications in patients undergoing VHR. The specific aims of the study were: to identify all studies analyzing iNPWT in patients undergoing VHR through systematic review; and to calculate pooled ORs of the rates of SSI, wound dehiscence, seroma and hernia recurrence between patients who received iNPWT and conventional dressings.

METHODS

Reporting methodology

Results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (www.prisma-statement.org). The protocol used in the present systematic review is available through PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/), where it was assigned the registration number CRD42014015479.

Literature search

Two reviewers (EWS and DML) independently performed the literature search to identify studies comparing the postoperative use of iNPWT and conventional dressings in patients who underwent abdominal wall reconstruction/repair for ventral hernia. The MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCOPUS databases were searched through October 2015 using the following key words: “negative pressure wound therapy” and “ventral hernia”. The MeSH terms and entry terms related to the key words were also used in this comprehensive literature search.

Titles and abstracts of potential articles for inclusion were independently examined. Full-text articles were retrieved and examined by both reviewers when their title and abstract did not provide sufficient information for a definite decision. When the two reviewers disagreed, a third investigator (HTC) was included and consensus was reached after discussion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, studies were required to meet the following criteria: the design was a comparative study published in the English-language literature; study subjects were adult patients (>18 years of age) who underwent VHR; the intervention was iNPWT (such as the Vacuum Assisted Closure V.A.C.Ò Therapy System, KCI Inc, USA); the comparison control group was conventional dressings (such as sterile gauze); and the study reported the rates of postoperative complications such as SSI, wound dehiscence, seroma, hernia recurrence, enterocutaneous fistula, etc. Exclusion criteria included the following: non-English literature or small sample sizes (<5 patients in each study group).

Methodological quality assessment

The Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) guidelines were used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies (19). A score ≥16 indicates a high-quality study; otherwise, the quality is low (<16). Two independent reviewers (EWS and DML) reviewed and scored each study. Discrepancies between scores were discussed and resolved between the reviewers.

Primary predictor variable and outcomes

The primary predictor variable was the use of iNPWT as defined by each included study. Outcomes measured included the rates of SSI, wound dehiscence, seroma formation and hernia recurrence, as defined in the included studies.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (EWS and DML) independently extracted data for: study details (design, first author, year of publication); demographics and patient descriptive statistics (age, size of hernia, body mass index, repair/reconstruction techniques and reinforcing materials used); number of patients in each study group; details of iNPWT application (mode, technique of application, duration of use); follow-up duration; and outcome measures (incidence of SSI, wound dehiscence, seroma, hernia recurrence, enterocutaneous fistula, hematoma and mean length of hospital stay).

Statistical analysis

RevMan 5.3 (Review Manager Version 5.3, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012) was used for meta-analysis. Results of the meta-analysis were assessed using OR with 95% CIs within a random-effects model. The Mantel-Haenzsel method was used for dichotomous outcomes. The variability in study outcomes was explored by calculating statistical heterogeneity using χ2 and inconsistency (I2) statistics; an I2 value ≥50% represented substantial heterogeneity. For all analyses, P≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

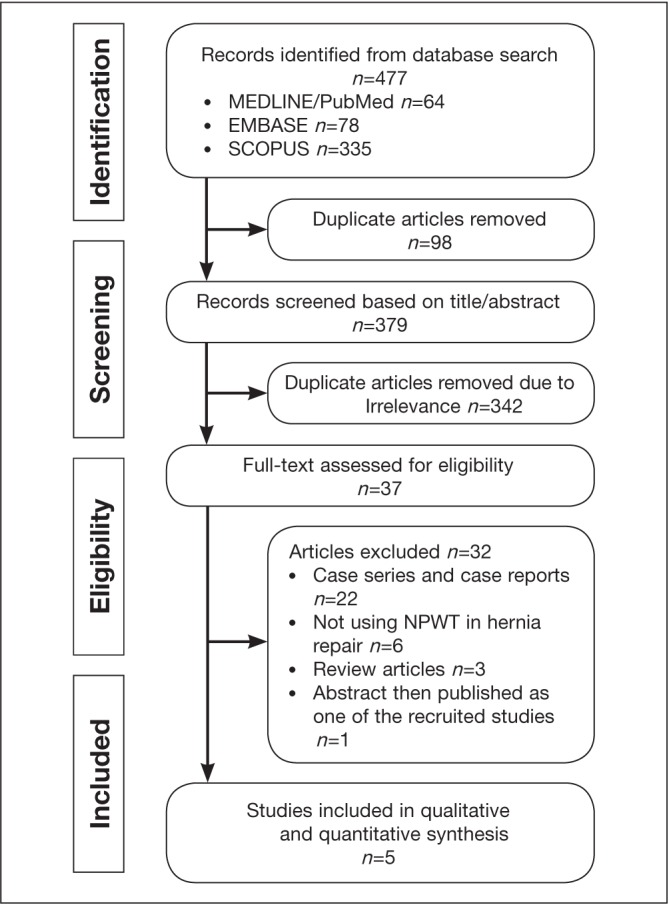

The database searches identified 477 citations. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 37 articles were included for full-text review. After application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria to the 37 retrieved articles, five relevant articles were included (14–18). The search and retrieval results are summarized in Figure 1. All five included studies were restrospective cohort designs. No study achieved high quality, with a mean MINORS score of 12.3 (range 11 to 14). Differences in patient demographics and preoperative risk factors between iNPWT and conventional dressing groups are summarized in Table 1. The studies varied in VHR techniques, reinforcing material used, NPWT (type, mode, duration) and conventional dressings, summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) statement of search results. NPWT Negative pressure wound therapy

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of dressings, repair technique, study populations and results of included studies

| Author (ref), year | Incisional NPWT | Conventional Dressing | Demographic difference between two groups | Ventral hernia repair technique and reinforcement material used | Key results | Mean follow-up | MINORS score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| n | Mode (duration) | n | Type | ||||||

| Condé-Green et al (14), 2013 | 23 | Continuous −125 mmHg (5 days) | 33 | Dry gauze dressings | None (age, previous abdominal surgery, BMI, and preoperative comorbidities) | Component separation in both groups Biologic matrix reinforcement in both groups |

NPWT decreased overall wound complications (22% versus 63.6%; P=0.020) and wound dehiscence (9% versus 39%; P=0.014) No statistically significant difference in SSI, seroma, and hernia recurrence |

15 months (4–36 months) | 13/24 |

| Pauli et al (15), 2013 | 49 | Continuous −75 mmHg (7 days)* | 70 | Dry gauze dressings | NPWT group: lower ASA Physical Status Classification; more component separations | Retro-rectus abdominus repair Synthetic mesh in clean fields and biologic matrix in contaminated fields |

No statistically significant difference in 30-day SSI rates (25.8% vs 20.4%; P=0.50) | N/A | 14/24 |

| Olona et al (16), 2014 | 5 | Continuous −125 mmHg (7 days) | 37 | N/A | None (in age and BMI) | Chevrel technique Synthetic mesh | NPWT decreased the number of days of postoperative drainage (4 versus 7 days) No statistically significant difference in SSI, hematoma, and seroma |

N/A | 11/24 |

| Gassman et al (17), 2014 | 29 | Continuous −125 mmHg (7 days) | 32 | dry occlusive dressings | NPWT group: more obese patients (21/29 versus 10/32), more cases with previous intra-abdominal infection (20/29 versus 9/32) | Component separation when primary fascial closure not possible Biologic matrix intraperitoneal underlay |

NPWT decreased SSI (17.2% versus 53.1%; P=0.01) No statistically significant difference in hematoma, seroma, skin flap necrosis, mesh removal, and hernia recurrence |

167 days | 11/24 |

| Soares et al (18), 2014 | 115 | Continuous −125 mmHg (3 days) | 84 | Dry gauze dressings | NPWT group: higher grade of surgical wound classifications according to CDC criteria, more anterior component separation | Large adipocutaneous flaps Component separation in all cases Synthetic mesh in all cases Sandwich technique with sythetic mesh plus biologic matrix when fascial closure not possible |

NPWT decreased SSI (8.7% versus 32.1%; P<0.01) No statistically significant difference in seroma, wound dehiscence, hernia recurrence |

8.7±9.9 months | 14/24 |

Or until the day of the patient’s discharge.

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI Body mass index; CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Georgia, USA); MINORS Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies; N/A Not applicable; NPWT Negative pressure wound therapy; ref Reference; SSI Surgical site infection

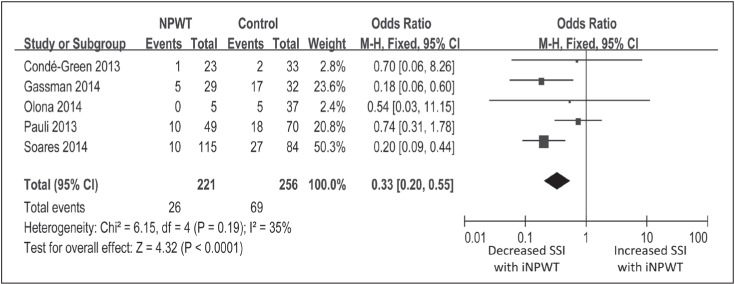

SSI

Five studies comprising 477 patients were included in the meta-analysis of SSI (14–18). In total, 11.8% (26 of 221) of the patients receiving iNPWT developed SSI compared with 27.0% (69 of 256) of patients receiving conventional dressings. The use of iNPWT after VHR was associated with a decreased incidence of SSI (OR 0.33 [95% CI 0.20 to 0.55]; P<0.0001). Studies were of low heterogeneity (I2=35%; P=0.19) (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Forest plot comparing the rates of surgical site infection (SSI) in patients receiving negative pressure wound therapy to closed incisions (iNPWT) versus conventional dressings following ventral hernia repair

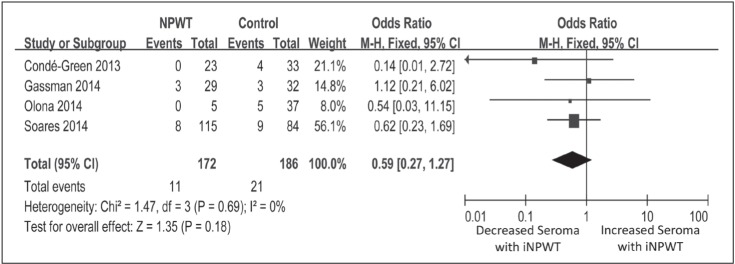

Seroma

Four studies reported the incidence of seroma in both groups (14,16–18). In total, 6.4% (11 of 172) of the patients receiving iNPWT developed seroma compared with 11.3% (21 of 186) of patients receiving conventional dressings. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of seroma on meta-analysis (OR 0.59 [95% CI 0.27 to 1.27]; P=0.18; I2 =0%; P=0.69) (Figure 3).

Figure 3).

Forest plot comparing the rates of seroma formation in patients receiving negative pressure wound therapy to closed incisions (iNPWT) versus conventional dressings following ventral hernia repair

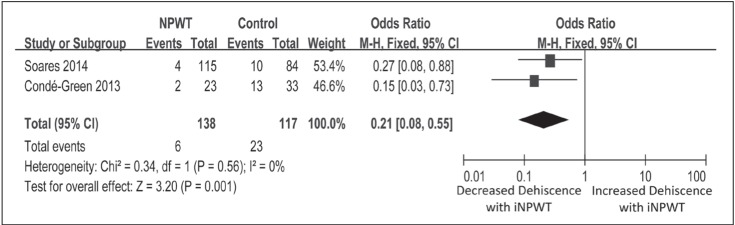

Wound dehiscence

Two studies reported the incidence of wound dehiscence in both groups (14,18). In total, 4.3% (six of 138) of the patients receiving iNPWT developed wound dehiscence compared with 19.7% (23 of 117) of patients receiving conventional dressings. The use of iNPWT after VHR was associated with a decreased incidence of wound dehiscence (OR 0.21 [95% CI 0.08 to 0.55]; P=0.001). Studies were of low heterogeneity (I2=0%; P=0.56) (Figure 4).

Figure 4).

Forest plot comparing the rates of wound dehiscence in patients receiving negative pressure wound therapy to closed incisions (iNPWT) versus conventional dressings following ventral hernia repair

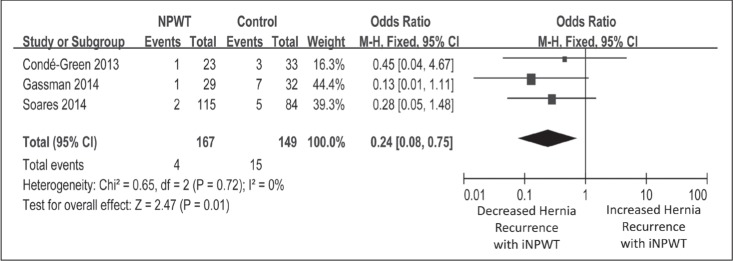

Hernia recurrence

Three of the included studies reported the incidence of hernia recurrence in both groups (14,17,18). In total, 2.4% (four of 167) of the patients receiving iNPWT developed hernia recurrence compared with 10.1% (15 of 149) of patients receiving conventional dressings. The use of iNPWT after VHR was associated with a decreased incidence of hernia recurrence (OR 0.24 [95% CI 0.08 to 0.75]; P=0.01). Studies were of low heterogeneity (I2=0%; P=0.72) (Figure 5).

Figure 5).

Forest plot comparing the rates of hernia recurrence in patients receiving negative pressure wound therapy to closed incisions (iNPWT) versus conventional dressings following ventral hernia repair

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to determine whether the application of iNPWT following VHR reduces wound complications and hernia recurrence compared with conventional dressings. We sought to identify all studies analyzing iNPWT in patients undergoing VHR through systematic review, and to perform a meta-analysis of the rates of SSI, wound dehiscence, seroma and hernia recurrence in patients who received iNPWT versus those who were treated with conventional dressings.

The results of the meta-analysis confirm our hypothesis that iNPWT following VHR reduces wound complications and suggests that it may also reduce hernia recurrence. SSI, wound dehiscence and ventral hernia recurrence were all markedly reduced (67% to 79% reduced odds) in patients receiving iNPWT versus conventional dressing. The findings of our quantitative analysis of the scientific literature highlight that iNPWT is a valid alternative to conventional dressings, demonstrating decreased wound complications (SSI and wound dehiscence) and ventral hernia recurrence for patients undergoing abdominal wall reconstruction/repair for ventral hernia.

Although we hypothesized that iNPWT would decrease wound complications, we did not predict that it would result in decreased hernia recurrence as our findings suggest. Given the proposed mechanism of iNPWT (splinting skin edges together, peri-incisional wound fluid removal, decreased edema and reduced bacterial burden), it is not readily apparent how hernia recurrence is affected. Studies that reported reduced hernia recurrence with the use of iNPWT did not propose potential mechanisms, nor did they analyze the factors that led to hernia recurrence. We hypothesize that reduced hernia recurrence may be a secondary benefit of reduced wound complications. Patients experiencing SSI and/or wound dehiscence following VHR often require mesh removal, which may result in relapse of their original hernia. This hypothesis is speculative and requires future studies to elucidate differences in patients experiencing hernia recurrence in iNPWT groups versus those in conventional dressing groups.

Aside from obvious benefits to the patient, reduction in wound complications and hernia recurrence would result in significant cost savings (20–23). Using inpatient nonfederal discharges for VHR from the 2001–2006 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, supplemented by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2006 National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery for outpatient estimates, Poulose et al (20) demonstrated a cost savings of $32 million for each 1% decrease in hernia recurrence and reoperation. In a cost analysis of all patients undergoing VHR for Ventral Hernia Working Group (VHWG) grade II hernias by Fischer et al (22), wound complications (hematoma, seroma, dehiscence, infection, midline ischemia requiring reoperation) and hernia recurrence were associated with significantly higher costs compared with patients who did not experience such complications ($48,164.1±51,181.4 versus $36,046.2±44,493.2 [P=0.015]; and $102,799.4±97,070.6 versus $36,582.6±40,734.3 [P=0.0095], respectively). Reductions in cost from prevention of wound complications and hernia recurrence need to be balanced against the cost of using iNPWT as a prophylactic measure in VHR. The direct costs of using NPWT and potential indirect costs (ie, increased length of stay) need to be weighed against the benefits of utilizing the technology. True cost savings could only be evaluated in randomized controlled trials investigating the use of iNPWT in VHR.

Given the potential for reduced complications and costs following VHR, identifying the appropriate patients to receive iNPWT is important. In 2010, the VHWG established a grading system for management of incisional ventral hernias (24). They proposed evidence-based recommendations for repair technique and reconstructive material according to grade. Using the VHWG grading system may similarly provide guidance for the identifying the appropriate patients for iNPWT following VHR. Risks for wound complications and hernia recurrence were variably defined among the included studies in this meta-analysis. Soares et al (18) used a modification of the VHWG classification (25) and found a significant reduction in SSI rates associated with iNPWT, but only in patients with higher-grade ventral hernia (18). Pauli et al (15) evaluated 119 patients with grade 3 (potentially contaminated) and grade 4 (infected) large VHRs with or without iNPWT. They reported no difference in SSI rate between the two groups. Gassman et al (17) reported that their 61 cases were ‘clean’ without referring to a specific hernia classification, and found iNPWT compared with conventional dressings decreased SSI (53% versus 17%; P=0.01) and hernia recurrence (22% versus 3.4%; P=0.05). Without a detailed and consistent risk stratification within the studies included in this meta-analysis, we could not perform subgroup analyses to evaluate the clinical efficacy of iNPWT based on ventral hernia grade. We encourage future reports to stratify patients according to ventral hernia grade for such comparisons to define which patients stand to benefit from application of iNPWT to VHR.

Our results did not demostrate decreased rates of seroma formation using iNPWT (6.4% versus 11.3%; P=0.18). Previous studies have demonstrated that the incidence of seroma formation can reach 18% (3). The main concern with seroma formation is conversion to SSI. Serial aspiration is an inconvenience to patients; however, if a seroma ultimately resolves uneventfully, it is a minor complication (26). Because SSI rates were shown to decrease with the use of iNPWT in the present meta-analysis, the lack of effect on seroma formation is not as clinically significant. Although decreased seroma formation is desired, iNPWT in VHR remains a potentially useful intervention to reduce overall wound complications based on our findings. Future randomized controlled trials are warranted to further elucidate the effect of iNPWT on the incidence of seroma, as well as the other outcomes assessed in the present meta-analysis of retrospective cohort studies.

Our meta-analysis did have limitations. The studies included were retrospective cohort designs with potential selection bias. However, differences between study groups often placed patients in the iNPWT cohort at higher risk. In the study by Gassman et al (17), patients receiving iNPWT had a higher incidence of previous intra-abdominal infection and patients with a body mass index >30 kg/m2. Patients receiving iNPWT had higher-grade hernias in the study by Soares et al (25). Pauli et al (15) reported that the conventional dressing group has a significantly lower American Society of Anesthesiology score. Given the retrospective nature of these studies, it is not surprising that the iNPWT cohort was generally at higher risk in most studies because surgeons may have decided to use more preventive measures (such as iNPWT) in patients they deemed high-risk for complications. With higher-risk patients populating the iNPWT cohort, the results of the present meta-analysis are potentially more telling as to its potential utility. In addition, not all studies reported each outcome analyzed. However, each outcome included >100 patients in both study groups, allowing data to be pooled across varying study conditions. Hernia recurrence can occur late into follow-up, and the studies included only reported follow-up data as late as 15 months postoperatively. The mode, technique and duration of iNPWT varied across studies. However, when pooled, the use of iNPWT demonstrated significant benefits, defining the optimal way to use iNPWT is needed. With the limitations of the current meta-analysis explained, further study is warranted using randomized controlled trials stratifying patients according to hernia grade, with long-term follow-up. Higher levels of evidence will allow for cost-benefit analysis and discovery of the optimal patients and mode/duration of iNPWT to use.

CONCLUSIONS

Systematic review and meta-analysis from current available data suggest that postoperative application of NPWT to closed incisions in VHR may decrease wound complications and hernia recurrence. Further high-quality studies are required to recommend the use of iNPWT as a standard of practice in this patient group.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee L, Mata J, Landry T, et al. A systematic review of synthetic and biologic materials for abdominal wall reinforcement in contaminated fields. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2531–46. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen MT, Berger RL, Hicks SC, et al. Comparison of outcomes of synthetic mesh vs suture repair of elective primary ventral herniorrhaphy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:415–21. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro PM, Rabelato JT, Monteiro GG, del Guerra GC, Mazzurana M, Alvarez GA. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the repair of ventral hernias: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arq Gastroenterol. 2014;51:205–11. doi: 10.1590/s0004-2803201400030008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauli EM, Rosen MJ. Open ventral hernia repair with component separation. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:1111–33. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer JP, Wink JD, Nelson JA, Kovach SJ., III Among 1,706 cases of abdominal wall reconstruction, what factors influence the occurrence of major operative complications? Surgery. 2014;155:311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levi B, Zhang P, Lisiecki J, et al. Use of morphometric assessment of body composition to quantify risk of surgical-site infection in patients undergoing component separation ventral hernia repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:559e–566e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovecchio F, Farmer R, Souza J, Khavanin N, Dumanian GA, Kim JY. Risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients undergoing ventral hernia repair. Surgery. 2014;155:702–10. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: A new method for wound control and treatment: Clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:563–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krug E, Berg L, Lee C, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the use of negative pressure wound therapy in traumatic wounds and reconstructive surgery: Steps towards an international consensus. Injury. 2011;42(Suppl 1):S1–S12. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(11)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stannard JP, Volgas DA, McGwin G, III, et al. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy after high-risk lower extremity fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:37–42. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318216b1e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janis JE, Kwon RK, Attinger CE. The new reconstructive ladder: Modifications to the traditional model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(Suppl 1):205S–212S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318201271c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohmen PM, Markou T, Ingemansson R, et al. Use of incisional negative pressure wound therapy on closed median sternal incisions after cardiothoracic surgery: Clinical evidence and consensus recommendations. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1814–25. doi: 10.12659/MSM.891169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orgill DP, Manders EK, Sumpio BE, et al. The mechanisms of action of vacuum assisted closure: More to learn. Surgery. 2009;146:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conde-Green A, Chung TL, Holton LH, III, et al. Incisional negative-pressure wound therapy versus conventional dressings following abdominal wall reconstruction: A comparative study. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71:394–7. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31824c9073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauli EM, Krpata DM, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJ. Negative pressure therapy for high-risk abdominal wall reconstruction incisions. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2013;14:270–4. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olona C, Duque E, Caro A, et al. Negative-pressure therapy in the postoperative treatment of incisional hernioplasty wounds: A pilot study. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2014;27:77–80. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000442873.48590.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gassman A, Mehta A, Bucholdz E, et al. Positive outcomes with negative pressure therapy over primarily closed large abdominal wall reconstruction reduces surgical site infection rates. Hernia. 2015;19:273–8. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares KC, Baltodano PA, Hicks CW, et al. Novel wound management system reduction of surgical site morbidity after ventral hernia repairs: A critical analysis. Am J Surg. 2015;209:324–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poulose BK, Shelton J, Phillips S, et al. Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: Making the case for hernia research. Hernia. 2012;16:179–83. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basta MN, Fischer JP, Kovach SJ. Assessing complications and cost-utilization in ventral hernia repair utilizing biologic mesh in a bridged underlay technique. Am J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer JP, Basta MN, Mirzabeigi MN, Kovach SJ., III A comparison of outcomes and cost in VHWG grade II hernias between Rives-Stoppa synthetic mesh hernia repair versus underlay biologic mesh repair. Hernia. 2014;18:781–9. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer JP, Wes AM, Wink JD, et al. Analysis of perioperative factors associated with increased cost following abdominal wall reconstruction (AWR) Hernia. 2014;18:617–24. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ventral Hernia Working G. Breuing K, Butler CE, et al. Incisional ventral hernias: Review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. 2010;148:544–58. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanters AE, Krpata DM, Blatnik JA, Novitsky YM, Rosen MJ. Modified hernia grading scale to stratify surgical site occurrence after open ventral hernia repairs. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:787–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner PL, Park AE. Laparoscopic repair of ventral incisional hernias: pros and cons. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]