Abstract

Background

In many randomized controlled trials, patients and doctors are more interested in the per-protocol effect than in the intention-to-treat effect. However, valid estimation of the per-protocol effect generally requires adjustment for prognostic factors associated with adherence. These adherence adjustments have been strongly questioned in the clinical trials community, especially after 1980 when the Coronary Drug Project team found that adherers to placebo had lower 5-year mortality than non-adherers to placebo.

Methods

We replicated the original Coronary Drug Project findings from 1980 and re-analyzed the Coronary Drug Project data using technical and conceptual developments that have become established since 1980. Specifically, we used logistic models for binary outcomes, decoupled the definition of adherence from loss to follow-up, and adjusted for pre-randomization covariates via standardization and for post-randomization covariates via inverse probability weighting.

Results

The original Coronary Drug Project analysis reported a difference in 5-year mortality between adherers and non-adherers in the placebo arm of 9.4 percentage points. By using modern approaches, we found that this difference was reduced to 2.5 (95% CI -2.1, 7.0).

Conclusions

Valid estimation of per-protocol effects may be possible in randomized clinical trials when analysts use appropriate methods to adjust for post-randomization variables.

Keywords: Per-protocol effect, intention-to-treat effect, inverse probability weighting, Coronary Drug Project, adherence

Clinical decision making relies heavily on the findings of randomized clinical trials. Because substantial societal resources are allocated to the conduct of these studies, it is surprising that randomized trial findings are often summarized by a single measure that provides incomplete clinical information: the intention-to-treat effect. In an intention-to-treat analysis individuals are assigned to the treatment arm they were randomized to, regardless of whether they actually took the treatment as intended in the study's protocol. In placebo-controlled trials, patients assigned to treatment may stop taking it and those assigned to placebo may start taking treatment. As a result, the intention-to-treat effect may be closer to the null than the effect that would have been found if all patients had taken their assigned study treatment exactly as specified by the study protocol, that is, the per-protocol effect or the effect under full adherence to protocol.

The intention-to-treat effect has well known advantages.1 However, patients and their doctors may be more interested in the per-protocol effect than in the intention-to-treat effect when making treatment decisions.2 In trials that try to detect harm, a closer-to-the-null-by-design intention-to-treat effect is misleading and generally discouraged. In the increasingly frequent pragmatic trials, the benefits of randomization may be overwhelmed by serious deviations from protocol, including lack of adherence to the assigned interventions and loss to follow-up. Therefore, in many randomized trials, intention-to-treat analyses need to be complemented with properly conducted per-protocol analyses that adjust for incomplete adherence.3

However, there is no universally accepted method to estimate per-protocol effects. The naïve approach commonly referred to as “per-protocol analysis” (that is, comparing only individuals who adhere to their assigned treatment while they adhere to it) is hardly a contender for a valid estimation of the per-protocol effect because this approach would only be valid if non-adherence occurred essentially at random.2 Adjustment for pre-randomization variables will generally help reduce bias in naïve per-protocol analyses, but such adjustment is not common in practice. In fact, most clinical trial protocols devote little, if any, attention to the estimation of the per-protocol effect.

Some of this lack of interest can be traced back to an influential article published in 1980 in the New England Journal of Medicine.4 This article had a chilling effect on subsequent attempts to conduct per-protocol analyses: investigators from the Coronary Drug Project (CDP) demonstrated that, among individuals assigned to placebo, the 5-year mortality risk was higher among those who did not adhere than among those who did adhere to the placebo pills. This finding is taught in courses around the world and often quoted as a reminder of the dangers of analyses that deviate from the intention-to-treat principle.

Because placebo cannot affect mortality, the difference between compliers and noncompliers in the CDP clearly indicates that adherence is a marker of good prognosis and that a comparison of adherers and non-adherers is inherently biased. That statistical adjustment, using the best methods available at that time, could not eliminate the bias was interpreted as an indication that analyses to estimate the per-protocol effect were to be distrusted, if not outright discouraged.

In the thirty-five years since the publication of the CDP paper, new statistical methods have been developed to adjust for protocol deviations.5, 6 These methods can validly incorporate pre- and post-randomization variables; therefore they will generally result in less biased per-protocol effect estimates than those obtained from naïve per-protocol analyses. Randomized trials that, like the CDP, compare sustained interventions over long periods are the best candidates to benefit from these new methods, which estimate more robust per-protocol effect estimates, to complement the usual intention-to-treat analyses.

Here we (i) revisit the CDP findings in light of technical and conceptual developments that have become established since 1980, and (ii) review the options available for the estimation of per-protocol effects today. We start by summarizing the CDP and its findings.

A brief summary of the CDP

Design and conduct of the CDP

The CDP was a 6-arm double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial designed to identify treatments that would reduce premature mortality in men with a history of myocardial infarction (MI).7, 8 The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Enrollment occurred between March 1966 and October 1969, and follow-up continued until late 1974 to early 1975. The trial compared five active treatments to placebo: clofibrate (ethyl chlorophenoxyisobutyrate, 1.8mg/day), low-dose equine estrogen (2.5mg/day), high-dose equine estrogen (5.0mg/day), dextrothyroxine (6mg/day), and nicotinic acid (3mg/day). Increased risk of adverse events was observed in the high- and low-dose estrogen arms and the dextrothyroxine arm; these arms were discontinued in 1970, 1973, and 1971, respectively.9

Men were eligible to participate if they were between 30-64 years of age at the time of randomization, had an ECG with documented MI at least 3 months before entry, a New York Heart Association functional class I (no limitation of physical activity) or II (slight limitation), no previous surgery for coronary artery disease, no other life-limiting diseases or conditions that could affect long-term follow-up, no contraindication for the study drugs, willingness to participate and to adhere to study drugs as assessed by a two-month control period, and no anti-coagulant therapy, lipid influencing drugs, or insulin use at baseline. Men were excluded if evidence suggested MI due to coronary artery embolism, aortic dissection, or prolonged arrhythmia.

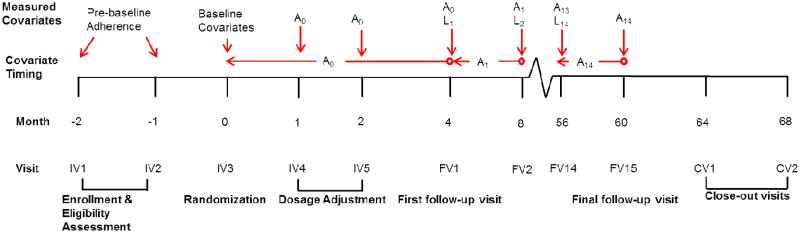

Randomization was within each of 53 study centers and by risk group, with low risk defined as having had only one previous MI and no associated complications, and high risk as having had more than one MI or one MI with complications. Figure 1 displays an overview of the study timeline. Three initial monthly visits were conducted to determine eligibility and to estimate adherence to placebo; randomization occurred at the third visit, and dosage was adjusted at two additional monthly visits. Patients were prescribed three pills daily at randomization and dosage was increased by up to 3 pills per visit, on the basis of drug tolerance, to a final dose of nine daily pills by the fifth visit. Follow-up visits were planned to occur every four months until study completion, dropout, or death.7 Up to three close-out visits were planned after study completion to assess any impact of drug withdrawal. Three of the study arms (both estrogen arms and the dextrothyroxine arm) were discontinued during follow-up because of adverse events.10-12

Figure 1.

Study timeline, Coronary Drug Project. Timing of study visits and variable measurement. Lt is the vector of post-randomization covariates measured at visit t and At is an indicator for adherence level for the period from t to just before t+1 measured at visit t+1. A0 is measured at follow-up visit 1 (FV1) or, for individuals who died or dropped out before FV1, at IV4 and IV5.

Clofibrate versus placebo: Published results in 1980

1103 patients were randomized to the clofibrate arm and 2789 to the placebo arm.9 Minimum follow-up duration for surviving participants was 54 months; 96% were followed for at least 5 years and 63% for at least 6 years. As of August 31, 1974, 7.4% of survivors in the clofibrate arm and 8.0% of those in the placebo arm had stopped attending study visits and were classified as lost to follow-up. At 56-60 months, 5.5% of the clofibrate arm and 4.2% of the placebo arm were receiving less than 20% of the prescribed dose (p-value= 0.28), and 11.5% of the clofibrate arm and 9.4% of the placebo arm were receiving less than 80% of the prescribed dose (p-value =0.20). Mean adherence to the maximum study dose was 77.1% in the clofibrate arm and 77.8% in the placebo arm; median adherence was 86.1% for clofibrate and 87.1% for placebo.9 The percentage of patients with adherence of less than 80% by the end of follow-up was 5.5% for the clofibrate arm and 9.4% in the placebo arm.9

The 5-year all-cause mortality was 20.0% for the clofibrate arm and 20.9% in the placebo arm (p-value = 0.55). The five-year incidence for the secondary combined outcome of death due to coronary heart disease or occurrence of definite non-fatal MI was 23.8% for clofibrate and 26.2% for placebo (p-value = 0.13). Adjustment for baseline characteristics did not materially alter the study results.9 The CDP Research Group concluded that there was no evidence that clofibrate reduced 5-year mortality.9

How the Coronary Drug Project convinced us that adjustment for non-adherence is futile

In 1980 the CDP investigators also compared the 5-year mortality risk between adherers and non-adherers within each arm. To calculate adherence, the clinic staff computed the percentage of capsules prescribed that were actually taken by the patient during the previous four months. This assessment was made by questioning the patient and/or counting the capsules returned at each visit. Adherence was categorized into one of five levels: 80-100%, 60-79%, 40-59%, 20-39%, and less than 20% adherence to prescribed dosage. Adherence was standardized by prescribed dosage, and the cumulative adherence was computed from this value until death or the end of year 5. Finally, cumulative adherence was dichotomized at less than 80% versus greater than or equal to 80% over the follow-up.4

In the placebo arm, 882 participants had a cumulative adherence of less than 80% (noncompliers) and 1813 participants had a cumulative adherence of greater than or equal to 80% (compliers) until death or end of follow-up. Among noncompliers, 28% died within the first 5 years of follow-up, compared with only 15% of compliers; a difference of over 13%. After adjustment for 40 baseline characteristics, the difference in 5-year mortality risk was still about 10%. The authors concluded that compliers and non-compliers must be different in ways not accounted for by the available data because a greater adherence to placebo is not expected to have a causal effect on the mortality risk. This inability to adjust for adherence in the placebo arm strongly suggests that any attempt at an adherence-adjusted analysis of the entire trial data would be futile. By extension, if adherence adjustment was not successful in the CDP, a large trial with extensive and detailed data collection at baseline and over time, why should we expect it to be successful in any other randomized trial?

An early 21st century update of the CDP placebo comparisons

The approaches to data analysis that were standard in 1980 would not necessarily be the primary choice today. A modern comparison of compliers and noncompliers in the placebo arm of the CDP would differ from the 1980 analysis.

We conducted a re-analysis of the placebo arm of the CDP to estimate the difference in 5-year mortality risk under adherence levels of <80% versus ≥80%. Because placebo should have no effect on the 5-year mortality risk, a non-null estimate would suggest that compliers and non-compliers are indeed irreconcilably different. On the other hand, a null estimate would increase confidence in our ability to sufficiently adjust for the differences between compliers and noncompliers when estimating the per-protocol effect.

Our re-analysis differs from the original 1980 analysis in three aspects: definition of adherence during missed visits, adjustment for baseline predictors of adherence, and adjustment for post-randomization predictors of adherence. We proposed updates to the 1980 analysis.

1. Definition of adherence

When a participant missed a study visit, his adherence to the placebo pills was unknown and therefore needed to be imputed. The 1980 analysis set adherence to 0% at missed visits, even though individuals may have partly adhered to placebo during the period preceding the missed visit. Because individuals were more likely to miss visits when they were about to die (mortality hazard ratio for those who did versus did not miss the previous visit was 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3 to 2.6), setting adherence to 0% may artificially increase the proportion of noncompliers among patients at high risk of death.

We updated the analysis by decoupling the classification of an individual as a noncomplier from his risk of death in the near future. To do so, we used past adherence history as an indicator of expected adherence by setting adherence at missed visits equal to adherence at the most recently attended visit, which may better reflect an individual's expected adherence. We censored individuals who missed more than three consecutive adherence measurements. See the Appendix for details.

2. Adjustment for pre-randomization risk factors

To adjust for baseline factors, the 1980 analysis used linear regression to model the 5-year mortality risk as a function of the baseline covariates, which were then evaluated at their average values in the study population. That was a typical choice at the time. We updated the analysis to a logistic regression model followed by standardization by the baseline covariates.

3. Adjustment for post-randomization risk factors

Because adherence varies over time, an analysis adjusted for only baseline variables may miss important prognostic factors that impacted adherence during the follow-up but that were not present at the time of randomization. The use of this post-baseline information will generally improve adherence-adjusted analyses. Indeed not adjusting for post-randomization variables makes the extreme assumption that, conditional on the baseline variables, adherence is independent of all measured and unmeasured post-randomization variables. The 1980 analysis, however, could not adjust for any post-baseline, time-varying covariates because no methods had yet been developed for this purpose at the time. As a result, the CDP investigators could not take advantage of much of the data so carefully collected over the course of the study.

We updated the analysis by using inverse probability weighting6 to adjust for post-randomization risk factors. Because the weight assigned to an individual at time t is a function of the individual's risk factor and adherence history through t, the analysis adjusts for post-randomization variables that are joint determinants of adherence and the outcome. This analysis makes the less extreme assumption that adherence was independent of the unmeasured but not the measured post-randomization variables. If all such variables were correctly measured and modeled,6, 13 the inverse probability weighted analysis would allow us to validly estimate the 5-year mortality that would have been observed in this trial if everyone in the placebo arm had adhered at least 80% to placebo compared with if no one in the placebo arm had adhered at least 80%. See the Appendix for more details.

4. Sensitivity analyses

We performed a variety of sensitivity analyses for dealing with missing adherence, including setting adherence to the cumulative average adherence up to each missed visit, setting adherence to 0% or 80% for up to 2 missed visits and then censoring, and setting adherence to half of the most recent available adherence value, with and without censoring. We also varied the definition of adherence by including or ignoring information about prescribed dosage, and changing the cut-point for dichotomous adherence to 70% and 90%. Finally, we included weights for censoring due to dropout, and permuted the covariates to assess the potential for over-fitting. Full results of the sensitivity analyses are provided in the Appendix.

Revisiting the CDP placebo comparisons

The CDP data tapes in the NIH data repository were corrupted in the 1990s and the data were irretrievable. Fortunately, Dr. Paul Canner, principal statistician of the CDP, had preserved a version of the de-identified data sets, which we used for our analyses. In collaboration with Dr. Canner, we will make the datasets user friendly. We will then submit the data sets and their documentation to the NIH data repository.

Replication of the 1980 CDP findings

As a check of the integrity of the data, we first replicated the main tables and results of the 1980 CDP article.4 To do so, we mimicked the methods described in the article as closely as possible (see Appendix for a detailed description).

Of 2630 individuals with non-missing values of the baseline covariates, 68.8% had a cumulative average adherence to placebo of at least 80%. We found a difference in 5-year mortality risk of 14.3 percentage points in the unadjusted analysis and of 10.9 after adjustment for baseline covariates. These estimates are within 1.5 percentage points of the estimates reported in the original 1980 analysis (unadjusted difference = 13.1%; adjusted difference = 9.4%). These small discrepancies are explained by the need to recalculate percent adherence and cumulative average adherence because of corruption in the original variables, and to correct some errors in coding for adherence at baseline and time of death. A similar analysis conducted in the clofibrate arm also showed a slight increase in 5-year mortality in the non-adherers compared to the original 1980 estimates (Table 1).

Table 1. Replication of the original results reported in reference 4, Coronary Drug Project.

| 5-year mortality, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline covariates | ||||

|

| |||||

| Cumulative Adherence < 80% | Cumulative Adherence ≥80% | Cumulative Adherence < 80% | Cumulative Adherence ≥80% | ||

|

| |||||

| Placebo arm: | Original 1980 analysis4 | 28.2 (25.3-31.1) | 15.1 (13.5-16.7) | 25.8 (22.9-28.7) | 16.4 (14.8-18.0) |

| Replication | 29.7 (26.6-33.0) | 15.5 (13.8-17.2) | 27.4 (24.5-30.3) | 16.5 (14.8-18.2) | |

|

| |||||

| Clofibrate arm: | Original 1980 analysis4 | 24.6 (20.1-29.1) | 15.0 (12.5-17.5) | 22.5 (18.0-27.0) | 15.7 (13.2-18.2) |

| Replication | 26.1 (21.5-31.2) | 15.3 (12.7-18.2) | 23.8 (19.7-27.8) | 16.4 (13.7-19.2) | |

A 2015 re-analysis of the CDP

As described above, our updated analysis differs from the original CDP analysis in three aspects: (1) handling of adherence at missed visits, (2) type of regression model for adjustment using baseline predictors, and (3) adjustment for post-randomization predictors of adherence using inverse probability weighting. Changing the handling of adherence at missed visits reduced our sample size by 217 individuals. These individuals missed more than three consecutive visits and were censored.

Adherence of less than 80% was associated with low prior adherence; acute coronary insufficiency, intermittent cerebral ischemic attack, congestive heart failure, and angina; recent use of diuretics and anti-arrhythmic agents; and smoking (Appendix Table 2). The adherence weights, truncated at their 99th percentile to prevent undue influence of outliers, had a mean of 1.01 (SD = 0.51) and a range of 0.02 to 3.94.

Table 2 shows the estimated difference in 5-year mortality risk between noncompliers and compliers in the placebo arm of the CDP, both in our replication of the 1980 analysis and in our updated analysis. The unadjusted difference in 5-year mortality risk (95% CI) was 11.0 percentage points (6.5, 15.6). The difference in 5-year mortality risk was 7.0 percentage points (2.7, 11.2) after adjustment for baseline covariates. Our handling of adherence and the use of logistic regression resulted in a 2.4 percentage point reduction compared with the CDP analysis that set missing adherence to 0 and used linear regression. The difference in 5-year mortality risk was 2.5 percentage points (-2.1, 7.0) after further adjustment for post-randomization covariates.

Table 2. Comparison of original and updated estimates for the placebo arm, Coronary Drug Project.

| 5-year mortality risk difference, % (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline variables* via linear regression | Adjusted for baseline variables* via logistic regression+ | Further adjusted for post-randomization variables** | |

| Replication of 1980 analysis (N = 2630) |

14.3 (10.8-17.8) | 10.9 (7.5-14.4) | 10.6 (7.3-14.0) | N/A |

| Updated 2015 analysis (N = 2401) |

11.0 (6.5-15.6) | 7.4 (3.0-11.8) | 7.0 (2.7-11.2) | 2.5 (-2.1-7.0) |

Adjusted for 39 baseline variables: age; race; risk group; number of prior myocardial infarctions; relative body weight; medical history; prescriptions of non-study medications; lab findings; blood pressure; cardiomegaly; ECG findings; cigarette smoking; and physical activity level (See Appendix Table 1 for details).

Adjusted for the 39 baseline variables (age, race, risk group, prior MIs, and relative body weight were baseline only) and 34 post-randomization variables: medical history; prescriptions of non-study medications; lab findings; blood pressure; cardiomegaly; ECG findings; cigarette smoking; and physical activity level (See Appendix Table 1 for details). Comparing individuals with <80% versus ≥80% at each visit.

The original 1980 analysis did not include logistic regression; we include it here for comparison purposes

That is, after adjustment, there was little survival difference between compliers and noncompliers in the placebo arm. This finding was robust to many possible variations of the analysis, which we explored in multiple sensitivity analyses (see Appendix).

Where does this leave us when estimating per-protocol effects?

The above shows that an analysis of the CDP that tries to adjust for adherence is not necessarily doomed. Our finding weakens the arguments against adherence-adjusted analyses of randomized trials for estimating the per-protocol effect. The question remains of how to better estimate such effect.

The two broad approaches to the estimation of per-protocol effects---instrumental variable estimation and direct adjustment for measured covariates--- each have shortcomings. Adjustment for noncompliance via instrumental variable estimation14 is desirable because it removes the need to collect data on prognostic factors that predict compliance. For example, Holme et al.15 recently used instrumental variable estimation to estimate the per-protocol effect of once-only sigmoidoscopy on colon cancer and overall mortality rate in a large randomized trial conducted in Norway. However, instrumental variable estimation requires strong assumptions in trials with interventions that, unlike a baseline sigmoidoscopy, need to be sustained during the follow-up. The use of instrumental variable estimations is even more questionable if the interventions are unmasked and potentially available to individuals in all arms (not a concern for the CDP).

Direct adjustment for measured covariates is another approach for per-protocol analyses of randomized trials of sustained interventions. Typically, these analyses require adjustment for pre- and post-randomization prognostic factors that predict adherence. Appropriate adjustment for post-randomization factors requires methods specifically designed for that purpose. These methods, collectively referred as g-methods and developed by Robins and collaborators,13, 16 include inverse probability weighting, which we used in our updated analysis of the CDP.

The key limitation of direct adjustment is the possibility of residual bias if the set of adjustment variables fails to include important joint predictors of adherence to the protocol and the outcome of interest (note that when the analysis fails to adjust for important joint predictors of both loss to follow-up and of the outcome of interest, then intention-to-treat effect estimates may also be biased because of informative censoring).17 In fact, there are examples, other than the CDP, in which adherers and non-adherers are so different with respect to their risk of developing the outcome that the available data are insufficient for direct statistical adjustment. For example, Holme et al. demonstrated that the mortality rate was greater in participants who refused to undergo a sigmoidoscopy compared with those who did undergo sigmoidoscopy, even after adjustment for multiple factors.15 However, the adjustment variables did not include cigarette smoking and other important prognostic factors, which, had they been available for inclusion might have explained the some of the observed difference in mortality rate.

Many randomized trials collect only limited data after randomization, which prevents valid estimation of per-protocol effects when instrumental variable estimation is not possible. Even in randomized trials that collect abundant baseline and post-randomization data, adjusted per-protocol effect estimates are not routinely presented along with intention-to-treat effect estimates. Appropriately adjusted per-protocol effect estimates can provide better estimates of both the efficacy of a treatment and the harms associated with the treatment in randomized trials. The omission of appropriately adjusted per-protocol effect estimates is especially problematic in randomized trials that assess potential harm and in those in which little effort is made to encourage adherence to the protocol, such as pragmatic and large simple trials.18 The lack of established methodologic standards for adjusted per-protocol estimates contributes to the problem because it creates uncertainty among investigators and sponsors who need to justify their analytic choices to journal editors and regulators.19

Conclusions

Widely held beliefs about the impossibility of conducting adherence-adjusted analyses may be partly based on weak empirical evidence and out-of-date methodology. Per-protocol effects can be validly estimated in clinical trials when sufficient data are available and appropriate adjustment methods are used. Supplementing intention-to-treat analyses with per-protocol effect estimates can allow richer, more nuanced inference from clinical trials. Clinical research would benefit from a concerted effort to establish clear guidelines for the definition and estimation of per-protocol effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Paul Canner, Principal Statistician of the Coronary Drug Project, and Roger Logan for his assistance. We thank Dean Follmann for his encouragement and assistance in the earlier stages of this project.

Funding: This work was partly funded by NIH grants R01 AI102634 and R01 HL080644.

Appendix

1. Compliers vs noncompliers in the placebo arm: Replication of the 1980 CDP results

Individuals were followed from randomization until the end of follow-up, which was defined as the earliest of 60 months, end of study (August 31, 1974), or death. Individuals who stopped attending study visits were coded as dropouts but not censored; vital status on August 31, 1975 was known for all but 1 dropout in the placebo arm and everyone in the clofibrate arm [1]. Of the 1103 individuals in the clofibrate arm, 311 died and 228 dropped out. Of the 2787 individuals in the placebo arm, 780 died and 546 dropped out. Excluding 128 patients who started follow-up after August 31, 1969 and therefore were not followed for the full 5 years did not materially change the estimates below.

Adherence

CDP participants were assessed for adherence to placebo at dosage adjustment visits at month 1 and 2 after randomization. Baseline adherence measure is taken as the average of percent adherence to placebo at these visits (IV4 and IV5). Adherence at each follow-up visit (IADH1-26) was classified as at least 80%, 60-79%, 40-59%, 20-39%, or less than 20% of the study dose over the previous 4-month period. Visits with missing adherence or prescription information because of missed visits, incomplete forms, or drop-out, and with no capsules prescribed, were assigned adherence equal to zero. Adherence was dose-adjusted by the percent of study dose prescribed during the previous 4-month period. Cumulative average adherence was then computed from percent adherence to prescription over the entire follow-up. Further details on the adherence measures can be found in the CDP documentation.

Covariates

We used the 40 covariates included in the 1980 paper [2] (Table A1), except “time since most recent MI”, which was missing for nearly half the sample (1123/2787 placebo arm participants, 421/1103 clofibrate arm participants) and had values less than 999 days for all others because of an error with missing indicator levels at some point in the past.

The baseline covariates used in the 1980 analysis were selected from the full set of approximately 135 baseline characteristics recorded at study entry by the CDP study team on the basis of their status as known or suspected risk factors for first MI [2, 3]. More information about these covariates and the selection process, as well as their relationships with recurrent MI among the CDP participants, was reported by the study team in 1974 [3].

Of the 39 covariates, 5 were recorded at baseline only and 34 were measured at baseline and during follow-up. Of the 34, 20 were recorded at every follow-up visit, while 14 were only recorded at annual-type visits which occurred at FV3, 6, 9, 12, and 15. Many additional variables were available in the CDP data both at baseline and during follow-up. We limited our analyses to the variables used in the original 1980 paper for the sake of comparability between our and previous results.

The 1980 paper did not specify whether the baseline covariates were dichotomized as in the main clofibrate analysis [1] or unchanged from the original coding as in interim analyses, in which the 40 covariates were selected [3]. However, Dr. Canner recalls that the 1980 paper dichotomized all covariates so we did the same.

Statistical Analysis

To adjust for baseline variables, we fit the linear regression model E[Y|CumA] = β0 + β1cumA + β2V where Y is an indicator for death by the end of follow-up (1: yes, 0: no), cumA is an indicator for at least 80% cumulative average adherence to placebo by the end of follow-up (1: yes, 0: no), and V is a vector including the 39 dichotomized baseline covariates to the model. The predicted values of this model for cumA=1 and cumA=0, standardized for the baseline covariates in V, were our estimates of the 5-year mortality risks. We used standardization rather than conditioning on a particular combination of values of the covariates because the estimates were sensitive to the choice of values and it is not clear what values the 1980 paper used. The 95% confidence intervals were obtained via nonparametric bootstrap with 500 samples.

2. Compliers vs noncompliers in the placebo arm: Re-Analysis of CDP

Handling of adherence at missed visits

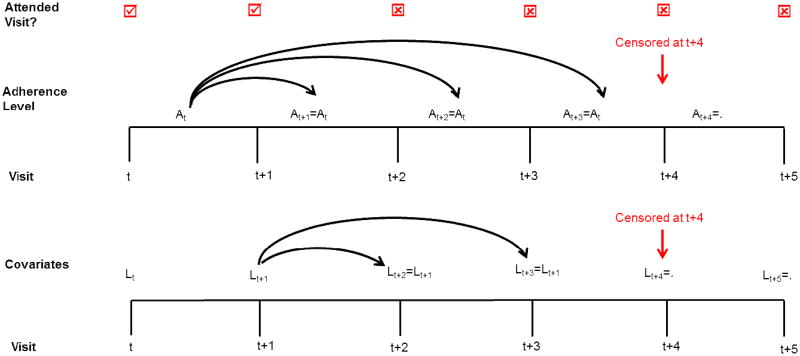

Instead of setting adherence level to 0 at some visits like the 1980 analysis did, we carried forward adherence from the most recent attended visit for up to two consecutive missed visits. Individuals who missed three or more consecutive visits were censored at the third consecutive missed visit (Figure A1). Under this scheme, 217 individuals were censored from all analyses because of missing adherence data, and 3 additional individuals were censored from the post-randomization adjusted analysis because of missing covariate information (Table A3).

Type of regression model for adjustment using baseline predictors

Instead of using linear regression for the outcome model adjusted for baseline variables, we used logistic regression because the outcome (death within 5 years) is binary. The model was logit(Pr[Y=1 | cumA, V, C15=0]) = β0 + β1cumA + β2V, where Y, cumA, and V are defined as above, and C15 is an indicator of censoring (1: yes, 0: no) by the end of follow-up at visit 15. The predicted values of this model for cumA=1 and cumA=0, standardized the estimates over the baseline covariates V, were our estimates of the 5-year mortality risks. Nonstandardized estimates when covariates were set to their median value were similar (risk difference: 4.1, 95% CI: 1.1, 7.2).

Adjustment for post-randomization predictors of adherence

To adjust for post-randomization predictors of adherence we used inverse probability (IP) weighting [4] for adherence at time t and applied the weights to the same outcome model used for baseline covariate adjustment: logit(Pr[Y=1 | cumA, V, C15=0]) = β0 + β1cumA + β2V.

The weights were estimated as follows. Let t be an index for visit number, where t=0 is the baseline visit. Each uncensored subject contributing to the outcome model received a stabilized IP weight

, where Mt is an indicator for measurement of adherence at visit t (1 if measured, 0 otherwise), At is the adherence level between visits t and t+1 (0: ≥80%, 1: <80%), Āt–1is adherence history through t, V is a vector of baseline covariates, L̄t is covariate history through t, and Ct =0 is an indicator for remaining in the study at visit t.

To estimate the denominator of the weights, we fit models in two stages. First, we fit the logistic model logit(Pr[Mt=1|A0, V, Āt–1, L̄t, Ct =0]) = β0t + β1A0 + β2V + β3At–1 + β4Lt–1 to all person-visits. Second, we fit the logistic model logit(Pr[At=0|A0, V, Āt–1, L̄t, Ct = 0, Mt =1]) =) = β0t + β1A0 + β2V + β3At–1+ β4Lt to all person-visits with measured adherence. Visits when adherence was not directly measured (Mt=0), but carried forward from the previous visit, the factor in the denominator of the adherence weight was 1 for that visit.

Similar models that did not include the time-varying covariates were fit to estimate the numerators of the weights. The final weight for each individual was the product of the measurement and adherence weights for that individual at each time point until censoring. As in previous studies[5, 6]we truncated the estimated IP weights at the 99th percentile to avoid undue influence of outliers. In our application, truncation of the weights did not materially change the estimates. For all analyses, 95% confidence intervals were obtained via nonparametric bootstrap with 500 samples.

Adjustment for censoring due to dropout

In a sensitivity analysis to adjust for potential bias from censoring due to dropout, we estimated stabilized IP censoring weights

by fitting the logistic regression model logit(Pr[Ct =0|A0, V, Āt–1, L̄t, Mt = 1]) = β0t + β1A0 + β2V + β3At–3 + β4Lt–1 to visits when adherence had been missing for the previous two visits; at all other times the conditional probability of remaining in the study is 1 for all previously uncensored individuals.

Similar models that did not include the time-varying covariates were fit to estimate the numerators of the stabilized censoring weights. The final weights for the censoring-adjusted models were the product of the censoring weights and the previously described adherence weights over all time points. To avoid undue influence of outliers, we again truncated the final weights at the 99th percentile.

Adding the inverse probability of censoring weights did not materially change the estimates; the estimated post-randomization-adjusted difference in 5-year mortality was 2.5% (-3.3, 8.8) after adjustment for censoring. The estimated censoring weights had a mean of 0.99 (SD = 0.06) and a range of 0.16 to 1.00. The combined adherence and censoring weights had a mean of 1.00 (SD = 0.50) and a range of 0.02 to 3.94.

Sensitivity Analyses

In our main analysis, we carried adherence forward from the previous visit for up to two consecutive missed visits and then censored individuals on their third consecutive missed visit. We also assessed other methods of dealing with missing adherence, which we present here and in Table A4. For all sensitivity analyses, 95% confidence intervals were obtained via bootstrap with 500 samples.

We ran 6 sensitivity analyses for dealing with missing adherence, all but one of which resulted in a null effect of adherence in the post-randomization adjusted analyses. When adherence was carried forward for two missed visits and set to 0 only from the third missed visit, instead of censoring the individual, the estimated difference in mortality at 5-years was 0.2% (-3.7, 4.1) after adjustment for post-randomization variables. When adherence was carried forward for two missed visits and set to 80% from the third missed visit, the estimated post-randomization-adjusted difference was 0.9% (-3.2, 4.9). When adherence was set to the cumulative average adherence reported prior to any missed visit, with no censoring, the estimated post-randomization-adjusted difference at 5 years was 1.1% (-3.4, 5.7).

When missing adherence was set to half that at the last available measurement, the estimated post-randomization adjusted difference was 1.4% (-2.6, 5.4) with no censoring, and 3.6% (-1.0, 8.1) with censoring at the third consecutive missed visit. When adherence was set to 0 for up to two missed visits and censored from the third consecutive missed visit (similar to 1980 analysis but with censoring after 3 missed visits) the estimated difference was 3.2% (-1.2, 7.5). These last two approaches are less successful at breaking the link between missing adherence and mortality and thus give estimates further from the null.

When adherence was set to 0 at all missed visits (the 1980 approach), the post-randomization-adjusted 5-year mortality difference was 7.6% (2.0, 13.1). We assessed the effect of definition of adherence in two ways: by ignoring prescribed dosage when calculating adherence, and by varying the cut-point for adherent versus non-adherent. Ignoring prescribed dosage produced estimates that were further from the null than the main analyses, particularly in the analyses adjusted for post-randomization variables and censoring which resulted in a 5-year mortality risk difference of 6.3% (-2.7, 15.2). We also varied the cut-point for binary cumulative adherence to 70% and to 90% for the unadjusted and baseline adjusted analyses. We were unable to adjust the cut-point for binary adherence at each visit because of the way this data were collected, so we were not able to run the post-randomization adjusted model at these levels. When cumulative adherence was dichotomized at 70%, the 5-year mortality difference was 8.2 percentage points (1.9, 14.4) in the baseline adjusted model. When cumulative adherence was dichotomized at 90% the 5-year mortality difference was -2.3 percentage points (-5.4, 0.8) in the baseline adjusted model. This latter finding may be explained because of the way the adherence data were coded by Canner with the midpoint of each category used for calculating cumulative adherence. Individuals with cumulative average adherence of 90% by the end of follow-up must have reported adherence in the 80-100% category at every visit while, and this was less common the longer an individual was under follow-up.

Some individuals were randomized after Aug 31, 1969 and therefore were administratively censored before completing the full 5 years of follow-up; excluding these individuals did not appreciably change the estimated difference in 5-year mortality risk (2.7%, -4.0, 9.3).

Finally, to check for over-fitting of the post-randomization adjusted analyses due to the large number of covariates in the model, we permuted the values of all baseline and time-varying covariates, while maintaining the link between adherence and 5-year mortality. We permuted the data 500 times, rerunning the analyses on each, and obtained the mean, 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the distribution. In the permuted dataset, all covariates are independent of adherence and survival. As expected, analysis of this permuted dataset resulted in estimates similar in size to the unadjusted analysis. The mean baseline adjusted risk difference was 11.1 percentage points (2.5th, 97.5th percentiles: 10.5, 11.8), and the mean post-randomization-adjusted risk difference was 11.3 percentage points (2.5th and 97.5th percentiles: 10.1, 12.3). These results suggest little or no role of over-fitting of the post-randomization adjusted models in the findings.

SAS code

We have provided the SAS code used for the main analyses. SAS 9.4 was used for all analyses. The code appendix contains the following programs:

-

Program 1: Data management

This program reads in the CDP dataset and defines the variables for the original and updated analyses. It creates two datasets for the placebo arm. Changing the value of ITR to 3 produces the same datasets for the clofibrate arm.- Binary.sas7bdat for crude and baseline adjusted analyses

- Censwt_ag.sas7bdat for post-randomization adjusted analyses

-

Program 2: Replication of 1980 analysis

This program estimates the crude and baseline adjustment using the original 1980 definition of adherence. The output gives the first 2 columns of row 1 of Table 2 when using the original adherence coding and the second column of row 2 when using the updated adherence coding. It also outputs the results for Table 1.

-

Program 3: Updated analyses with baseline variables

This program estimates the crude and baseline adjustment using updated definition of adherence and outputs columns 1 and 3 of row 2 of Table 2. Changing the adherence variable input allows estimation of the third column of row 1 in Table 2.

-

Program 4: Updated analysis with post-randomization covariates

This program requires the restricted cubic spline macro developed by F.E. Harrell[7, 8] in order to run. It estimates the association between adherence and death using adjustment for post-randomization covariates using inverse probability weighting and outputs final column for row 2 of Table 2.

Figure A1.

Censoring scheme for re-analyses of the Coronary Drug Project. Lt is the vector of covariates measured at visit t and At is an indicator for adherence level for the period from t to just before t+1. When an individual misses a study visit, the most recent covariate and adherence values are carried over from the previous inter-visit period. An individual is censored at the date of their third consecutive missed study visit. Covariates are therefore carried forward up to two consecutive missed visits, and adherence is carried forward up to three intervals between missed visits.

Table A1. Covariates used for adjustment, Coronary Drug Project.

| Covariate | Variable Code | Measured at: | Levels when dichotomized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | |||

| Age at entry (years) | IAGE | Baseline only | ≥55 vs <55 |

| Race | IRC | Baseline only | White vs not white |

| Lifestyle characteristics: | |||

| Cigarette smoking | ICG1-6 | Annual visits only | Any/none |

| Current habitual level of physical activity in leisure time | IJOB34-39 | Annual visits only | “Vigorous or Moderate” vs “Light or Sedentary” |

| Medical history: | |||

| Risk group | IRK | Baseline only | “Low risk (1 previous MI with no complications)” vs “High risk (>1 previous MI or MI with complications)” |

| Number of myocardial infarctions at baseline | NMI | Baseline only | ≥2 vs <2 |

| Time since most recent myocardial infarction | LMI | Baseline only | Dropped because of high missingness |

| Relative body weight | RBW | Baseline only | ≥1.15 vs <1.15 |

| History of congestive heart failure (yes = suspect or definite) | KLIN1; ICCL1-26 | All visits | Ever at Baseline: yes/no Since last visit: yes/no |

| History of angina pectoris (yes = suspect or definite) | KLIN2; ICCL27-52 | All visits | Ever at Baseline: yes/no Since last visit: yes/no |

| History of acute coronary insufficiency (yes = suspect or definite) | KLIN3; ICCL53-78 | All visits | Ever at Baseline: yes/no Since last visit: yes/no |

| History of intermittent cerebral ischemic attack (yes = suspect or definite) | KLIN5; ICCL157-182 | All visits | Ever at Baseline: yes/no Since last visit: yes/no |

| History of intermittent claudication (yes = suspect or definite) | KLIN7; ICCL235-260 | All visits | Ever at Baseline: yes/no Since last visit: yes/no |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | WTPB32-47 | All visits | ≥130 vs <130 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | WTPB61-76 | All visits | ≥85 vs <85 |

| New York Heart Association functional class | NIHA1-11 | Annual visits only | “Any limitation” vs “no limitation” |

| Cardiomegaly on chest X-ray (yes = probable or definite) | IXRAY1-22 | Annual visits only | Yes/no |

| Prescription of non-study medications: | |||

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | IMDCT29-56 | All visits | Current at baseline: yes/no Since last visit yes/no |

| Digitalis | IMDCT57-84 | All visits | Current at baseline: yes/no Since last visit yes/no |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | IMDCT85-112 | All visits | Current at baseline: yes/no Since last visit yes/no |

| Diuretics | IMDCT113-140 | All visits | Current at baseline: yes/no Since last visit yes/no |

| Antihypertensives other than diuretics | IMDCT141-168 | All visits | Current at baseline: yes/no Since last visit yes/no |

| Lab findings: | |||

| Serum total bilirubin (mg/dl) | ZLABB1; ZLAB4-18 | All visits | ≥0.5 vs <0.5 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dl) | ZLABB4; ZLAB91-105 | All visits | ≥250 vs <250 |

| Serum triglyceride (meq/L) | ZLABB5; ZLAB120-134 | All visits | ≥5.0 vs <5.0 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl) | ZLABB6; ZLAB149-163 | All visits | ≥7.0 vs <7.0 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (K-A units) | ZLABB7; ZLAB178-192 | All visits | ≥7.5 vs <7.5 |

| Plasma urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | ZLABB8; ZLAB207-221 | All visits | ≥16 vs <16 |

| Plasma fasting glucose (mg/dl) | ZLABB9; ZLAB236-250 | All visits | ≥100 vs <100 |

| Plasma one-hour glucose, after 75g oral load (mg/dl) | ZLABB10; ZLAB265-279 | All visits | ≥180 vs <180 |

| White blood cell count (cells/mm3) | WBC1-11 | Annual visits only | ≥7500 vs <7500 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/mm3) | WBC12-22 | Annual visits only | ≥4500 vs <4500 |

| Hematocrit (%) | WBC23-33 | Annual visits only | ≥46 vs <46 |

| ECG findings: | |||

| Q/QS pattern on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | IECG1-36 | Annual visits only | Any/None |

| ST segment depression on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | IECG37-72 | Annual visits only | Any/None |

| T-wave findings on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | IECG73-108 | Annual visits only | Any/None |

| ST segment elevation on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | IECG109-144 | Annual visits only | Any/None |

| Ventricular conduction defect | IECG193-204 | Annual visits only | Any/None |

| Premature ventricular beats (frequent ventricular ectopic beats) (Note: any does not include premature atrial or nodal beats) | IECG205-216 | Annual visits only | Any/None |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | IECG277-88 | Annual visits only | ≥70 vs <70 |

Table A2. Predictors of low adherence (<80%), Coronary Drug Project.

| Covariate | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Adherence history: | |

|

| |

| Low adherence | |

| pre-baseline | 1.32 (1.11, 1.58) |

| at baseline | 1.18 (1.01, 1.37) |

| at most recent visit | 23.40 (21.12, 25.92) |

|

| |

| Demographics: | |

|

| |

| Age ≥ 55 years at baseline | 1.05 (0.94, 1.16) |

|

| |

| Race (not white) | 0.96 (0.78, 1.17) |

|

| |

| Lifestyle characteristics: | |

|

| |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| at baseline | 1.30 (1.11, 1.51) |

| at most recent visit | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) |

|

| |

| Current habitual level of physical activity in leisure time (light or sedentary) | |

| at baseline | 0.90 (0.81, 1.01) |

| at most recent visit | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) |

|

| |

| Medical history: | |

|

| |

| Risk group (>1 previous MI or MI with complications) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.11) |

|

| |

| Number of prior MIs (≥2) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) |

|

| |

| Relative body weight (≥1.15) | 1.04 (0.94, 1.15) |

|

| |

| Congestive heart failure | |

| at baseline | 1.13 (0.96, 1.32) |

| at most recent visit | 2.14 (1.73, 2.66) |

|

| |

| Angina pectoris | |

| at baseline | 0.98 (0.88, 1.11) |

| at most recent visit | 1.22 (1.08, 1.36) |

|

| |

| Acute coronary insufficiency | |

| at baseline | 0.91 (0.799, 1.04) |

| at most recent visit | 4.97 (3.96, 6.24) |

|

| |

| Intermittent cerebral ischemic attack | |

| at baseline | 1.18 (0.92, 1.52) |

| at most recent visit | 2.31 (1.56. 3.42) |

|

| |

| Intermittent claudication | |

| at baseline | 1.06 (0.88, 1.27) |

| at most recent visit | 1.03 (0.85, 1.26) |

|

| |

| Systolic blood pressure (≥130 mmHg) | |

| at baseline | 1.07 (0.95, 1.21) |

| at most recent visit | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) |

|

| |

| Diastolic blood pressure (≥85 mmHg) | |

| at baseline | 1.04 (0.92, 1.18) |

| at most recent visit | 1.03 (0.91, 1.16) |

|

| |

| New York Heart Association functional class (any limitation) | |

| at baseline | 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) |

| at most recent visit | 1.05 (0.93, 1.19) |

|

| |

| Cardiomegaly on chest X-ray | |

| at baseline | 0.96 (0.83, 1.12) |

| at most recent visit | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) |

|

| |

| Prescription of non-study medications: | |

|

| |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | |

| at baseline | 0.96 (0.69, 1.33) |

| at most recent visit | 0.86 (0.64, 1.16) |

|

| |

| Digitalis | |

| at baseline | 0.73 (0.60, 0.90) |

| at most recent visit | 1.34 (1.13, 1.61) |

|

| |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | |

| at baseline | 0.58 (0.42, 0.80) |

| at most recent visit | 1.37 (1.11, 1.69) |

|

| |

| Diuretics | |

| at baseline | 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) |

| at most recent visit | 0.86 (0.74, 1.01) |

|

| |

| Antihypertensives other than diuretics | |

| at baseline | 1.17 (0.92, 1.48) |

| at most recent visit | 0.89 (0.72, 1.10) |

|

| |

| Laboratory findings: | |

|

| |

| Serum total bilirubin (≥0.5 mg/dl) | |

| at baseline | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) |

| at most recent visit | 0.93 (0.84, 1.03) |

|

| |

| Serum total cholesterol (≥250 mg/dl) | |

| at baseline | 0.88 (0.78, 0.99) |

| at most recent visit | 1.03 (0.92, 1.16) |

|

| |

| Serum triglyceride (≥5.0 meq/L) | |

| at baseline | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25) |

| at most recent visit | 0.91 (0.81, 1.02) |

|

| |

| Serum uric acid (≥7.0 mg/dl) | |

| at baseline | 0.93 (0.82, 1.04) |

| at most recent visit | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) |

|

| |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (≥7.5 K-A units) | |

| at baseline | 1.13 (1.00, 1.27) |

| at most recent visit | 0.93 (0.82, 1.05) |

|

| |

| Plasma urea nitrogen (≥16 mg/dl) | |

| at baseline | 0.94 (0.84, 1.05) |

| at most recent visit | 1.01 (0.90, 1.12) |

|

| |

| Plasma fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dl) | |

| at baseline | 0.89 (0.79, 1.01) |

| at most recent visit | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) |

|

| |

| Plasma one-hour glucose, after 75g oral load (≥180 mg/dl) | |

| at baseline | 0.91 (0.80, 1.03) |

| at most recent visit | 1.17 (1.04, 1.33) |

|

| |

| White blood cell count (≥7500 cells/mm3) | |

| at baseline | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) |

| at most recent visit | 1.05 (0.91, 1.21) |

|

| |

| Absolute neutrophil count (≥4500 cells/mm3) | |

| at baseline | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) |

| at most recent visit | 1.01 (0.87, 1.15) |

|

| |

| Hematocrit (≥46%) | |

| at baseline | 1.02 (0.91, 1.14) |

| at most recent visit | 0.90 (0.81, 1.01) |

|

| |

| ECG findings: | |

|

| |

| Q/QS pattern on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | |

| at baseline | 0.85 (0.74, 0.97) |

| at most recent visit | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) |

|

| |

| ST segment depression on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | |

| at baseline | 1.19 (1.02, 1.39) |

| at most recent visit | 0.99 (0.86, 1.15) |

|

| |

| T-wave findings on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | |

| at baseline | 1.03 (0.90, 1.19) |

| at most recent visit | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) |

|

| |

| ST segment elevation on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | |

| at baseline | 0.60 (0.44, 0.82) |

| at most recent visit | 1.33 (1.02, 1.73) |

|

| |

| Ventricular conduction defect | |

| at baseline | 0.82 (0.55, 1.23) |

| at most recent visit | 0.90 (0.65, 1.25) |

|

| |

| Premature ventricular beats (frequent ventricular ectopic beats) | |

| at baseline | 1.41 (1.05, 1.90) |

| at most recent visit | 1.41 (1.10, 1.80) |

|

| |

| Heart rate (≥70 beats per minute) | |

| at baseline | 0.85 (0.76, 0.96) |

| at most recent visit | 1.13 (1.01, 1.27) |

Table A3. Outcome status and baseline characteristics for censored and uncensored individuals in the updated analyses, Coronary Drug Project.

| Covariate | Prevalence among censored individuals, N = 217 (%) | Prevalence among uncensored individuals, N = 2413 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome status | ||

| Death within 5 years | 15.2 | 20.4 |

| Adherence history: | ||

| Low adherence pre-baseline | 11.5 | 6.0 |

| Demographics: | ||

| Age ≥ 55 years at baseline | 38.3 | 43.4 |

| Race (not white) | 8.3 | 6.8 |

| Lifestyle characteristics: | ||

| Cigarette smoking | 52.1 | 36.1 |

| Current habitual level of physical activity in leisure time (light or sedentary) | 71.9 | 69.1 |

| Medical history: | ||

| Risk group (>1 previous MI or MI with complications) | 30.4 | 34.3 |

| Number of prior MIs (≥2) | 19.4 | 19.3 |

| Relative body weight (≥1.15) | 44.7 | 46.0 |

| Congestive heart failure | 12.9 | 15.9 |

| Angina pectoris | 58.1 | 57.4 |

| Acute coronary insufficiency | 18.4 | 15.8 |

| Intermittent cerebral ischemic attack | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Intermittent claudication | 10.1 | 8.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure (≥130 mmHg) | 56.7 | 50.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (≥85 mmHg) | 46.5 | 35.4 |

| New York Heart Association functional class (any limitation) | 56.2 | 53.1 |

| Cardiomegaly on chest X-ray | 17.5 | 17.8 |

| Prescription of non-study medications: | ||

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 5.5 | 5.1 |

| Digitalis | 10.1 | 14.7 |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| Diuretics | 14.3 | 13.6 |

| Antihypertensives other than diuretics | 8.3 | 6.7 |

| Laboratory findings: | ||

| Serum total bilirubin (≥0.5 mg/dl) | 52.5 | 51.6 |

| Serum total cholesterol (≥250 mg/dl) | 50.7 | 45.9 |

| Serum triglyceride (≥5.0 meq/L) | 50.2 | 49.4 |

| Serum uric acid (≥7.0 mg/dl) | 43.3 | 43.8 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (≥7.5 K-A units) | 46.1 | 47.8 |

| Plasma urea nitrogen (≥16 mg/dl) | 47.5 | 53.1 |

| Plasma fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dl) | 48.4 | 40.9 |

| Plasma one-hour glucose, after 75g oral load (≥180 mg/dl) | 41.0 | 39.2 |

| White blood cell count (≥7500 cells/mm3) | 48.4 | 44.2 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (≥4500 cells/mm3) | 51.2 | 44.7 |

| Hematocrit (≥46%) | 60.8 | 58.1 |

| ECG findings: | ||

| Q/QS pattern on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | 64.5 | 61.3 |

| ST segment depression on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | 22.6 | 24.7 |

| T-wave findings on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | 53.0 | 48.5 |

| ST segment elevation on antero-lateral, postero-inferior, or antero-septal recording | 6.0 | 3.8 |

| Ventricular conduction defect | 1.8 | 4.3 |

| Premature ventricular beats (frequent ventricular ectopic beats) | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| Heart rate (≥70 beats per minute) | 53.5 | 43.9 |

Table A4. Sensitivity analyses for the difference in 5-year mortality for <80% adherence minus ≥80% adherence among 2630 individuals with complete baseline data in the placebo arm, Coronary Drug Project.

| 5-year mortality difference, % (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity analysis | N | Unadjusted | Adjusted for baseline variables | Further adjusted for post-randomization variables |

| Method to assign % adherence at missed visits % adherence carried forward for 2 missed visits, set to 0 from third consecutive missed visit onwards |

2626 | 6.0 (2.3, 9.7) | 3.1 (-0.3, 6.6) | 0.2 (-3.7, 4.1) |

| % adherence carried forward 2 missed visits, set to 80% from third consecutive missed visit onwards. | 2626 | 8.4 (4.4, 12.5) | 4.9 (1.1, 8.6) | 0.9 (-3.2, 4.9) |

| % adherence set to cumulative % adherence through last available visit at all subsequent missed visits | 2623 | 8.6 (4.5, 12.7) | 5.1 (1.3, 8.8) | 1.1 (-3.4, 5.7) |

| % adherence set to half the adherence at last available visit for all missed visits | 2623 | 7.9 (4.3, 11.5) | 4.8 (1.4, 8.1) | 1.4 (-2.6, 5.4) |

| % adherence set to half the adherence at last available visit up to 2 missed visits, censored from third consecutive missed visit onwards | 2413 | 12.5 (8.2, 16.9) | 8.2 (4.3, 12.1) | 3.6 (-1.0, 8.1) |

| % adherence set to 0 for 2 missed visits, censored from third consecutive missed visit onwards | 2413 | 11.7 (7.5, 15.8) | 3.1 (-0.3, 6.6) | 3.2 (-1.2, 7.5) |

| Original 1980 analysis (missing adherence set to 0 at all visits) with adjustment for post-randomization covariates | 2627 | --- | --- | 7.6 (2.0, 13.1) |

| Ignore prescribed dosage when calculating adherence No adjustment for censoring |

2415 | 11.6 (5.8, 17.4) | 7.6 (2.3, 13.0) | 5.8 (0.2, 11.5) |

| Adjustment for censoring via IP weighting | 2385 | 12.0 (6.3, 17.8) | 8.3 (3.1, 13.4) | 6.3 (-2.7, 15.2) |

| Definition of adherence Binary adherence cut-point at 70% |

2413 | 13.5 (6.9, 20.1) | 8.2 (1.9, 14.4) | --- |

| Binary adherence cut-point at 90% | 2413 | -0.2 (-3.4, 3.0) | -2.3 (-5.4, 0.8) | --- |

| Exclude individuals who started after Aug 30, 1969 No adjustment for censoring |

2315 | 11.0 (6.3, 15.6) | 6.7 (2.4, 11.0) | 2.5 (-2.1, 7.0) |

| Adjustment for censoring via IP weighting | 2289 | 11.0 (6.3, 15.8) | 7.0 (2.6, 11.4) | 2.7 (-4.0, 9.3) |

| Updated analysis, with adjustment for censoring via IP censoring weights | 2385 | 11.2 (6.5, 16.0) | 7.3 (3.0, 11.6) | 2.5 (-3.8, 8.8) |

| Updated analysis, with covariates set to median values | 2410 | --- | 4.1 (1.1, 7.2) | --- |

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Trial registration number and trial register: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier – NCT00000482

References

- 1.Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:109–112. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.83221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernán MA, Hernandez-Diaz S. Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clin Trials. 2012;9:48–55. doi: 10.1177/1740774511420743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernán MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. Randomized trials analyzed as observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:560–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-8-201310150-00709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the coronary drug project. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1038–1041. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010303031804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark SD, Robins JM. A method for the analysis of randomized trials with compliance information: an application to the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Control Clin Trials. 1993;14:79–97. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. The coronary drug project. Design, methods, and baseline results. Circulation. 1973;47:I1–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.3s1.i-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Factors influencing long-term prognosis after recovery from myocardial infarction--three-year findings of the coronary drug project. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:267–285. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coronary Drug Progject Research Group. The Coronary Drug Project. Findings leading to discontinuation of the 2.5-mg day estrogen group. JAMA. 1973;226:652–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coronary Drug Progject Research Group. The Coronary Drug Project. Findings leading to further modifications of its protocol with respect to dextrothyroxine. JAMA. 1972;220:996–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Coronary Drug Project. Initial findings leading to modifications of its research protocol. JAMA. 1970;214:1303–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robins JM, Hernán MA. Estimation of the causal effects of time-varying exposures. In: Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, editors. Longitudinal data analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall/RC Press; 2008. pp. 553–599. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Instruments for causal inference: an epidemiologist's dream? Epidemiology. 2006;17:360–372. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000222409.00878.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holme O, Loberg M, Kalager M, et al. Effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:606–615. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robins JM. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with sustained exposure periods - Application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Mathematical Modelling 1986; 7: 1393-1512. Errata in Computers and Mathematics with Applications. 1987;14:917–921. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little RJ, D'Agostino R, Cohen ML, et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eapen ZJ, Lauer MS, Temple RJ. The imperative of overcoming barriers to the conduct of large, simple trials. JAMA. 2014;311:1397–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Food and Drug Administration. [accessed 16 November 2015];Guidance for industry: determining the extent of safety data collection needed in late stage premarket and postapproval clinical investigations (draft guidance) 2012 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM291158.pdf.

Appendix References

- 1.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231(4):360–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the coronary drug project. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(18):1038–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010303031804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Factors influencing long-term prognosis after recovery from myocardial infarction--three-year findings of the coronary drug project. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27(6):267–85. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56(3):779–88. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cain LE, Logan R, Robins JM, et al. When to initiate combined antiretroviral therapy to reduce mortality and AIDS-defining illness in HIV-infected persons in developed countries: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):509–15. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing Inverse Probability Weights for Marginal Structural Models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrell FE. Clinical Biostatistics. Duke University Medical Center; 1988. %rcspline macro. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devlin TF, Weeks BJ. Spline functions for logistic regression modeling. Proc Eleventh Annual SAS Users Group International; Atlanta, Georgia. February 9-12; Cary NC: SAS Institute; 1986. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.