Abstract

A small molecule library consisting of 45 compounds was synthesized based on the bacterial metabolite ethyl N-(2-phenethyl) carbamate. Screening of the compounds revealed a potent analogue capabale of inhibiting several strains of Methicillin Resistant S. aureus biofilms with low to moderate micromolar IC50 values.

Introduction

Over the last several years antibiotic resistance has increasingly become a grave threat to human health.1 Antimicrobial resistant bacteria accounts for more than two million infections and approximately 23,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.2 One of the most serious antibiotic resistant bacteria is Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). MRSA is the causative agent of more than 400,000 hospitalizations and even more alarming is that it is responsible for nearly 50% of all deaths in the U.S. that stem from antibiotic resistant infections.3

MRSA is a genetically evolved form of S. aureus and is resistant to the β-lactam class of antibiotics (penicillin, amoxicillin, oxacillin, methicillin and others).4 Outside of genetic resistance markers, many strains of MRSA have the ability to colonize surfaces and adapt a biofilm mode of growth.5 Biofilms are defined as a surface attached community of bacteria encased in an extracellular matrix of biomolecules and bacteria within a biofilm are upwards of 1000-fold more resistant to antibiotics then their free-floating bretheren.6 This is especially problematic since as much as 33% of the human population is persistently colonized with S. aureus biofilms, with 2% colonized by MRSA, providing essentially a continuous reservoir for which this opportunistic bacteria can spread and cause infection.7, 8

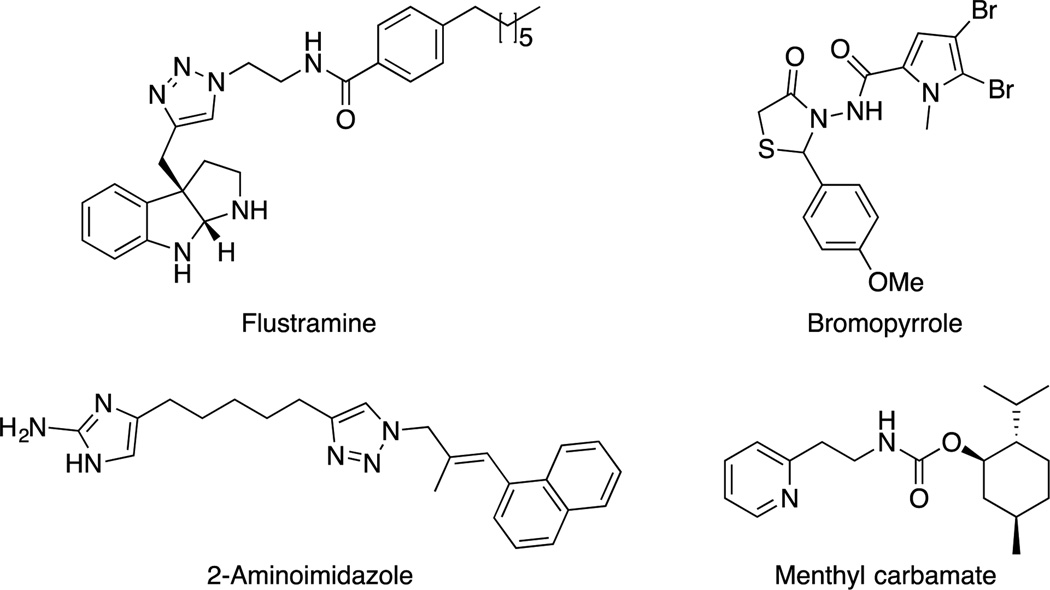

Relatively, few classes of MRSA biofilm inhibitors have been discovered. Inspiration for biofilm inhibitors is often drawn from marine organisms, which have evolved the ability to produce and secrete molecules that are capable of modulating biofilm attachment and growth.9 Discovery of new classes of MRSA biofilm inhibitors is of great interest as only a relatively small number of molecular scaffolds are known to inhibit MRSA biofilms including: 2-aminoimidazole derivatives,10–14 flustramine analogues,15, 16 menthyl carbamates,17, 18 bromopyrrole analgoues,19 and cembranoids (Fig 1).20

Fig 1.

Various MRSA biofilm inhibitor classes.

Previously, it was shown that the bacterial metabolite ethyl N-(2-phenethyl) carbamate (2b) displays moderate antibiofilm activity against several strains of bacteria.21 An initial structure activity relationship (SAR) study performed by Yamada et al. also revealed that this scaffold could be tuned for enhanced activity. Subsequently, our group expanded these studies and identified a number of structurally unrelated carbamates that were potent inhibitors of biofilm formation.17 Recently, we also established that 2b was able to sensitize cancer cells to the effects of marine toxins.22 This result has prompted us to further investigate the SAR of 2b in the context of MRSA biofilm inhibition. Herein, we report a second generation SAR study of 2b in the context of MRSA biofilm inhibition.

Results and discussion

Biofilm inhibition testing of the natural product 2b

Initial testing of the metabolite 2b for bacterial biofilm inhibition of medically relevant MRSA strains was performed at a 200 μM concentration. The lead compound (2b) displayed weak biofilm inhibiting properties, inhibiting only 30.7%, 27.6%, 37.9%, 7.7%, and 22.2% for MRSA strains 44, 1685, 43300, 700789, and 1753 as determined by a crystal violet reporter assay (Table 1).23 Interestingly, compound 2b induced biofilm formation in strains 1556, 1770, 811 and 33591.

Table 1.

Biofilm inhibition and IC50 data for 2b and 3j.

| MRSA Strain | % Inhibition (200 μM 2b) |

% Inhibition (200 μM 3j) |

IC50 (μM 3j) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 30.7 | 80.8 | 72.0 ± 5.0 |

| 1556 | −40.0 | 77.3 | 18.2 ± 4.0 |

| 1685 | 27.6 | 91.9 | 73.6 ± 2.9 |

| 43300 | 37.9 | 91.6 | 12.8 ± 4.3 |

| 700789 | 7.7 | 93.9 | 39.1 ± 5.8 |

| 1770 | −6.6 | 61.1 | 151.9 ± 4.4 |

| 811 | −66.2 | 50.8 | 215.0 ± 7.6 |

| 33591 | −10.1 | 65.2 | 111.9 ± 7.3 |

| 1753 | 22.2 | 90.2 | 60.5 ± 3.2 |

SAR studies through analogue synthesis of 2b

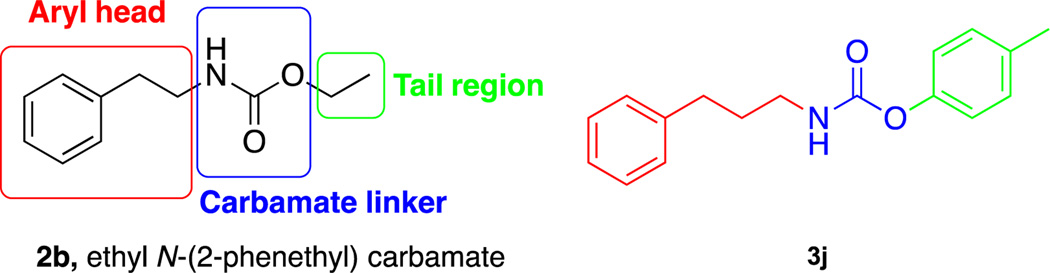

An SAR study was performed to identify more potent compounds capable of inhibiting multiple strains of MRSA biofilm development with the caveat of focusing on structural space close to the natural product itself. The SAR study was performed by a strategy of modifying the aryl head, tail region and carbamate linkage (Fig 2). An analogue library was constructed by carrying out matrix syntheses consisting of the displayed amines and various chloroformates (Fig 3). The aryl head was modified by shortening/extending the tail length to methyl, ethyl, propyl, butyl, hexyl, octyl and decyl chloroformates, as well as incorporating aryl components such as anisole, phenyl and tolyl functionalities. Each compound of the library was screened at a concentration of 200 μM against 9 different strains of MRSA. From the screen, analogue 3j consisting of the propyl length aryl amine head and tolyl tail was the most active analogue across the spectrum of MRSA strains. Compound 3j was more potent at 200 μM than the natural product, inhibiting biofilm formation by 80.8%, 77.3%, 91.9%, 91.6%, 93.9%, 61.1%, 50.8%, 65.2% and 90.2% for MRSA strains 44, 1556, 1685, 43300, 700789, 1770, 811, 33591 and 1753 (Table 1).

Fig 2.

Derivatization strategy of the natural product (2b) and active compound (3j) from SAR study.

Fig 3.

Matrix syntheses of analogue library.

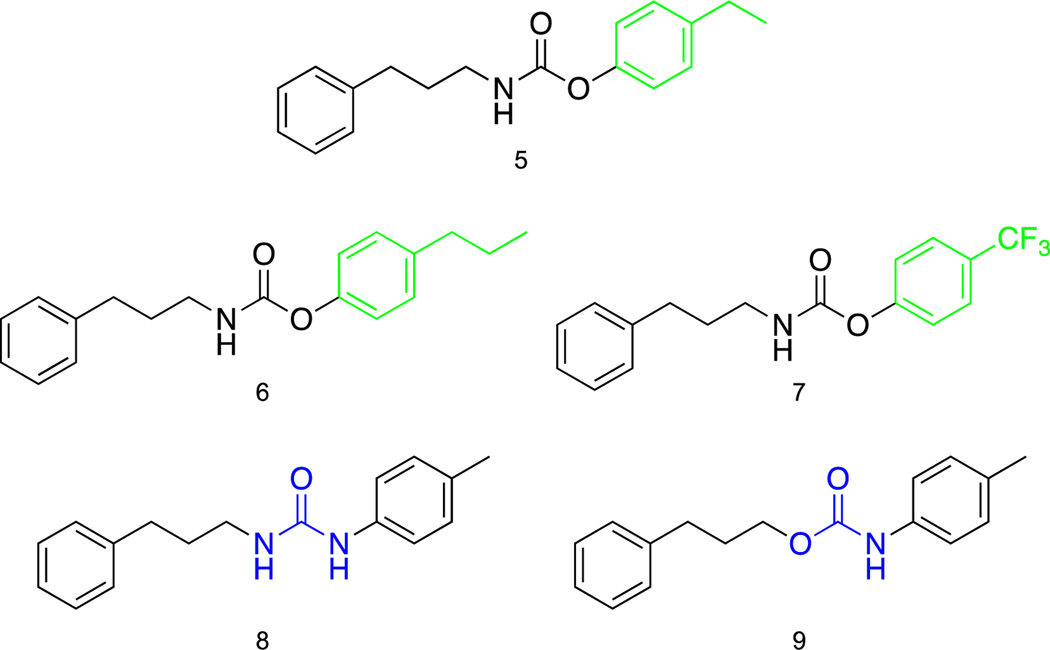

With the active compound in hand further modifications were performed to better understand the compounds structural needs for activity (Fig 4). The first set of changes made to 3j were swapping the para-methyl substituent for para-ethyl (5) and para-propyl (6) substituents. The ethyl and propyl substituted compounds 5 and 6 gave similar results to the lead compound 3j for strains 1685, 43300, 1556, 44 and 33591 (Table 2). The analogues displayed repressed biofilm activity for 1753, 700789 and 1770, however both derivatives showed superior activity for MRSA strain 811 inhibiting biofilm formation 75.1% and 73.4% for 5 and 6 respectively. At this point we opted to swap the electron donating aliphatic substituents for an electron withdrawing trifluoromethyl group (7). Changing the alkyl chains to a trifluoromethyl group resulted in a drastic loss in biofilm inhibition for all bacterial strains compared to parent compound 3j. The carbamate linkage was modified to a urea derivative (8) resulting in a significant decline of activity against all MRSA strains. The directionality of the carbamate linkage was then reversed and compared to lead compound 3j. The reverse carbamate 9 displayed comparable biofilm inhibiting properties as the lead 3j for MRSA strains 1685, 43300, 1770 and 44. For strains 1753, 700789, 1556 and 33591 biofilm inhibition capabilities were substantially abrogated. Analogue 9 did, however, inhibit biofilm formation of strain 811 by 61.0%, which is more potent than lead compound 3j. None of the previous modifications were capable of inhibiting biofilm formation with as much potency as compound 3j across the spectrum of MRSA strains.

Fig 4.

Further SAR studies of compound 3j.

Table 2.

(%) Biofilm inhibition data for compounds 5–9 at 200 μM.

| MRSA Strain |

5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 76.4 | 59.5 | 39.9 | 48.2 | 70.4 |

| 1556 | 60.9 | 60.3 | 4.2 | −63.2 | 43.7 |

| 1685 | 81.9 | 79.7 | 59.5 | 48.2 | 87.8 |

| 43300 | 76.1 | 69.8 | 69.5 | 30.4 | 84.4 |

| 700789 | −13.3 | 4.5 | 5.3 | −49.5 | 40.7 |

| 1770 | −14.2 | −16.0 | −41.0 | −43.9 | 45.8 |

| 811 | 75.1 | 73.4 | 56.5 | 10.4 | 61.0 |

| 33591 | 54.2 | 52.8 | −139.3 | 3.9 | 39.6 |

| 1753 | 22.1 | 28.9 | 38.4 | 29.7 | 43.8 |

Dose response study of analogue 3j

Dose response studies were performed with 3j against each MRSA strain to generate IC50 values and quantify activity (Table 1 and See SI for IC50 graphs). The IC50 values for 3j were determined to be 72.0 ± 5.0 μM, 18.2 ± 4.0 μM, 73.6 ± 2.9 μM, 15.7 ± 4.0 μM, 39.1 ± 5.8 μM, 151.9 ± 4.4 μM, 215.0 ± 7.6 μM, 111.9 ± 7.3 μM and 60.5 ± 3.2 μM for MRSA strains 44, 1556, 1685, 43300, 700789, 1770, 811, 33591 and 1753.

Time kill curve of analogue 3j

In order to determine whether analogue 3j was acting through a toxic or non-toxic mechanism, bacterial growth was measured as a function of time. Methicillin resistant S. aureus strain 43300 was grown in the presence/absence of 3j (15.7 μM). Bacterial growth was checked at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h time points (SI Fig 1). Based on the analysis of the time kill curve, bacterial growth devoid of analogue 3j and bacterial growth in the presence of 3j appear to be nearly identical throughout the 24 h time period. This result suggests that compound 3j is most likely acting through a non-toxic mechanism.

Confirmation of 3j biofilm inhibiting properties

Carbamates are readily known to be susceptible to hydrolysis in solution. To confirm that 3j is responsible for the biofilm inhibition and not any potential degradation by-products, the corresponding amine (3) and hydrolyzed chloroformate (j) were tested for biofilm inhibition against MRSA strain 43300 (SI Table 1). 3 and hydrolyzed j were tested at 200 μM and 3j’s IC50 value (15.7 μM). The amine (3) and hydrolyzed j were tested separately and together. Neither compound separately or in combination at either concentration inhibited biofilm formation of any significant amount. This suggests that indeed 3j is inhibiting biofilm formation and not any hydrolyzed degradation by-products.

Experimental section

Materials and methods

All reagents and solvents for synthesis were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Triethylamine (TEA) was dried by refluxing over CaH2, followed by distillation and storage over 4 Å molecular sieves. Deuterated solvents were acquired from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (CIL). Purification was performed using 60-mesh standard silica gel from Sorbtech. 1H NMR (300 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were recorded at 25 °C on Varian Mercury spectrometers. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm relative to the respective NMR solvent. Mass spectra were recorded on Thermo Fisher Scientific Exactive Plus MS (ESI).

Synthesis

General procedure for compounds 1a–4j

A flame dried round bottom flask under N2 atmosphere was filled with anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL). To this flask was added amine (1.0 mmol) and TEA (3.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C and the chloroformate (0.9 mmol) was slowly added. The reaction was stirred until completion as determined by TLC. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the resulting residue was purified by flash chromatography to furnish pure product.

General procedure for compounds 5–9

A flame dried round bottom flask under N2 atmosphere was filled with anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL). To this flask was added sequentially triphosgene (0.4 mmol), TEA (3.0 mmol), and amine (1.0 mmol). The reaction was stirred for 15 min and then the solvent was removed in vacuo. The resulting solid was dissolved in THF (5 mL) followed by TEA (3.0 mmol). The flask was cooled to 0 °C and the corresponding alcohol or amine (1.0 mmol) was slowly added. The reaction was allowed to stir for 5 min before being refluxed overnight. After refluxing, the solvent was removed in vacuo and the resulting residue was purified by flash chromatography affording pure product.

Biological

Bacteria and media

Staphylococcus aureus strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA, as ATCC # (BAA-44, BAA-1556, BAA-1685, 43300, 700789, BAA-1770, BAA-811, 33591 and BAA-1753). S. aureus was grown in tryptic soy broth with 0.5% glucose supplement (TSB-G) with shaking or on tryptic soy agar at 37 °C.

Biofilm inhibition assay

One day cultures (24 h) were subcultured to an OD600 of 0.01 into TSB-G. Aliquots (1 mL) were taken from the subcultured media and added to small culture tubes for each concentration of each compound to be tested. Compound from a 100 mM stock solution was added to the small culture tubes to give the desired concentration of compound (50–200 μM). Aliquots (100 μL) of each sample were added into each well of a row of a microtiter plate with two control lanes containing no compound and one row containing only water. The plate was covered in a damp plastic container and incubated under stationary conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. The media and planktonic bacteria were discarded and the plates were washed with water and 110 μL of a 0.1% crystal violet solution was added to each well and left to stand for 30 min. The crystal violet was discarded and the plate was washed with water and 200 μL of EtOH was added to each well and was allowed to stand for 10 min, then 125 μL from each well was transferred to a polystyrene microtiter plate and the OD540 of each well was measured and the water lanes were subtracted out. The percentage of biofilm inhibition was calculated.

Conclusions

In summary, an analogue library of the bacterial metabolite 2b was constructed in a matrix fashion. Testing of the compounds revealed a single analogue (3j) that was potent against several strains of medically relevant MRSA. Compound 3j inhibited bacterial biofilm formation by 50.8 – 93.9% at 200 μM against MRSA strains respectively and low to moderate micromolar IC50 values ranging from 15.7 ± 4.0 μM – 215.0 ± 7.6 μM. The ease of synthesis and simplistic nature of 3j make it an attractive option for bacterial biofilm control of MRSA. We are currently testing these analogues for their ability to potentiate cancer chemotherapeutics to determine if there is a substantial correlation between these two apparently disparate activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the V foundation, the National Institutes of Health (GM055769 and DE022350), and Faculty of Science, Mahidol University for their generous support of this work.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Roca I, Akova M, Baquero F, Carlet J, Cavaleri M, Coenen S, Cohen J, Findlay D, Gyssens I, Heure OE, Kahlmeter G, Kruse H, Laxminarayan R, Liebana E, Lopez-Cerero L, MacGowan A, Martins M, Rodriguez-Bano J, Rolain JM, Segovia C, Sigauque B, Taconelli E, Wellington E, Vila J. New microbes and new infections. 2015;6:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher HW, Corey GR. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:S344–S349. doi: 10.1086/533590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim D, Strynadka NCJ. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2002;9:870–876. doi: 10.1038/nsb858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen SK, Rainey PB, Haagensen JA, Molin S. Nature. 2007;445:533–536. doi: 10.1038/nature05514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen TB, Givskov M. International journal of medical microbiology : IJMM. 2006;296:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505–520. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee SS, Ray P, Aggarwal A, Das A, Sharma M. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:742–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards JJ, Melander C. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2287–2294. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes S, Huigens Iii RW, Su Z, Simon ML, Melander C. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2011;9:3041–3049. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00925c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su Z, Peng L, Worthington RJ, Melander C. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:2243–2251. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeagley AA, Su Z, McCullough KD, Worthington RJ, Melander C. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2013;11:130–137. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26469b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlani RE, Yeagley AA, Melander C. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;62:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huigens Iii RW, Rogers SA, Steinhauer AT, Melander C. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2009;7:794–802. doi: 10.1039/b817926c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minvielle MJ, Bunders CA, Melander C. MedChemComm. 2013;4:916–919. doi: 10.1039/C3MD00064H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunders C, Cavanagh J, Melander C. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2011;9:5476–5481. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05605k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers SA, Whitehead DC, Mullikin T, Melander C. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2010;8:3857–3859. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers SA, Lindsey EA, Whitehead DC, Mullikin T, Melander C. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2011;21:1257–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rane RA, Sahu NU, Shah CP. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012;22:7131–7134. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ami [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada A, Kitamura H, Yamaguchi K, Fukuzawa S, Kamijima C, Yazawa K, Kuramoto G-Y-S, Wang M, Fujitani Y, Uemura D. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 1997;70:3061–3069. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahome P, Beauchesne K, Pedone A, Cavanagh J, Melander C, Zimba P, Moeller P. Marine Drugs. 2015;13:65. doi: 10.3390/md13010065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.