Abstract

An important issue that should be taken into consideration when applying the molecules in photodynamic therapy (PDT) of cancer is the occurrence of homo-resonance energy transfer process between them. We have determined the probability of energy transfer for sodium zinc (II)-2,9,16,23-phthalocyanine tetracarboxylate (ZnPc(COONa)4) molecules in aqueous NaOH solution. The homo-quenching effect of the molecule was also measured by calculating the diffusion controlled bimolecular rate constant of kq = 6.5 × 109 M−1s−1, which did not show a significant competition with the rate constant of homo-resonance energy transfer process at the applied concentration of the molecules (6 μM). The Förster radius (R 0) for ZnPc(COONa)4 molecules was calculated to be 42 Å. The availability of these calculations should facilitate the potential application of ZnPc(COONa)4 molecule as an anticancer drug in PDT.

Keywords: Resonance energy transfer, Donor, Phthalocyanine

Introduction

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a quantum mechanical method in which radiationless energy is transferred from the donor (d) to acceptor (a) molecules without emission of a photon [1–5]. It is a significant physical phenomenon that offers considerable scope for the understanding of some biological systems along with possible applications in thin-film device development [4, 6]. Four criteria have to be satisfied in order for FRET to occur [6–8]. These are: (i) The emission dipole moment of the donor, the absorption dipole moment of the acceptor (quencher), and the center-to-center position vector between the molecules must be approximately parallel to each other. (ii) The acceptor absorption spectrum must have a sufficient degree of overlap with the donor emission spectrum, which is referred to as spectral overlap integral. (iii) The center-to-center distance between the donor and acceptor molecules must be within a specified range, typically 1 to 10 nm [9–11]. (iv) The donor should have noticeable fluorescence quantum yield and the absorption coefficient of the acceptor has to be sufficiently large (εa ≥1000 M−1cm−1).

The major FRET applications are based on Förster length between the donor and acceptor at a distance of R 0 from each other. It is recognized as the donor–acceptor distance when 50% of the excitation energy of the donor molecule is transferred to the acceptor molecule [7, 8, 12]. The other half is dissipated by all other mechanisms accounting for fluorescence, internal conversion, and intersystem crossing. The excitation energy decreases rapidly as the distance between the donor and acceptor fluorophores increases more than the Förster radius [6, 7, 12].

ZnPc(COONa)4 is a second-generation far-red-absorbing photosensitizer with an appreciable singlet oxygen quantum yield [13]. These aspects are essential for any photosensitizer to be potentially applied as an anticancer drug in PDT of cancer [14, 15]. Occurrence of the homo-FRET process can result in a strong reduction of the photoactivity of the ZnPc(COONa)4 molecule, especially its singlet oxygen generation. As a result, its effectiveness in PDT applications is reduced.

The aim of the current work was to carry out theoretical calculations on the factors of homo-FRET process assuming its occurence between ZnPc(COONa)4 molecules in inhomogeneous aqueous solution of NaOH. Moreover, the diffusion-controlled bimolecular rate constant was calculated and compared with the rate constant of the FRET process.

Experimental section

Material

The structural formula of the sodium zinc (II)-2,9,16,23-phthalocyanine tetracarboxylate (ZnPc(COONa)4) molecule is shown in Fig. 1. It was dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH. Chemicals were used as supplied.

Fig. 1.

The structural formula of the sodium zinc (II)-2,9,16,23-phthalocyanine tetracarboxylate (ZnPc(COONa)4) molecule

Equipment

The electronic ground-state absorption spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer employing quartz cells (10 × 10 mm path length) at room temperature. The increment step of the measurement was 0.1 nm.

Fluorescence excitation and emission spectra were recorded on a JASCO-FP 6500 spectrofluorometer using a 1 cm-path-length cuvette at room temperature.

Fluorescence quantum yield and lifetime

Fluorescence quantum yield of the donor (fd) was obtained by the comparative method [15]:

| 1 |

where fsd is the fluorescence quantum yield of the standard. If and Isd are the areas under the fluorescence emission spectra of the donor and the standard, respectively. Od and Osd are, respectively, the optical densities of the donor and standard at the excitation wavelengths. n2 and n2sd are the indices of refraction of solvents used for the donor and standard, respectively. Both the samples and standard were excited at the same wavelength. The optical density of the solutions at the excitation wavelength was 0.05.

Natural radiative lifetime (τ0) was calculated using the Strickler–Berg equation [16]. The fluorescence lifetime (τd) was calculated by Eq. (2):

| 2 |

Results and discussion

Usually, UV–Vis spectra of phthalocyanines (Pcs) demonstrate typical electronic spectra with two strong absorption bands known as B and Q bands [17–19]. The B band in the UV region at 300–400 nm is attributed to deep π-π* transition from HOMO to LUMO of the Pc [20–22] with a small contribution from n-π* transition, whereas the Q band in the visible region at 600–750 nm originates from the less deep π-π* transition of HOMO to LUMO of the Pc (−2).

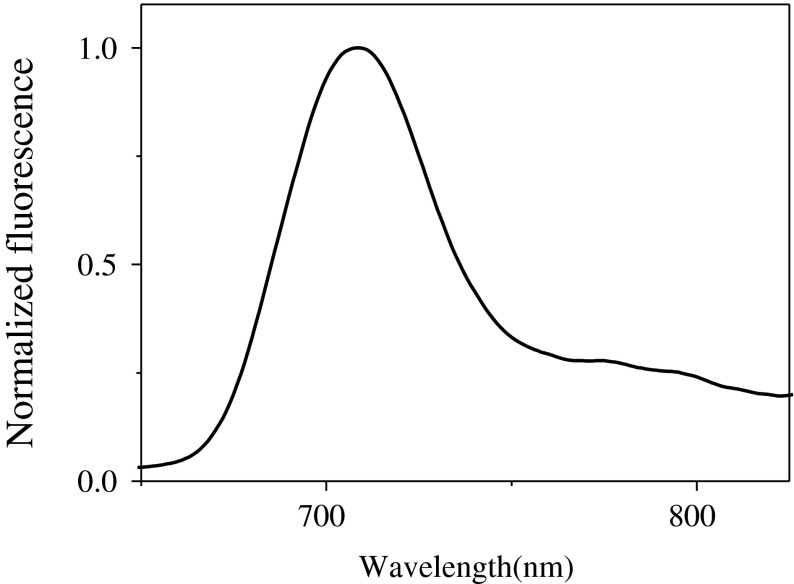

The ground state electronic absorption spectrum of ZnPc(COONa)4 in aqueous solution of NaOH is shown in Fig. 2. Its feature is similar to those of metal phthalocyanine molecules [17–20]. The farthest red region of the spectrum is located at Q1(0,0) band (λ = 691 nm) with extinction coefficient of ε691nm = 1.31 × 104 M−1cm−1. The fluorescence spectrum was the same for all excitation wavelengths, demonstrating the presence of only one fluorescing species with its maximum peak at λmax = 702 nm (Fig. 3). The proximity of the maximum wavelengths of the Q band of the excitation spectrum and absorption suggests that the nuclear arrangement of the ground and excited states are similar and are not affected by the excitation. Fluorescence quantum yield of the donor was evaluated to be fd = 0.1.

Fig. 2.

The UV–Vis absorption spectrum of ZnPc(COONa)4 in aqueous medium of 0.1 M NaOH

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence spectra of ZnPc(COONa)4 in aqueous medium of 0.1 M NaOH at room temperature. Excitation wavelength (λex) = 355 nm. [ZnPc(COONa)4] = 6 μM

Fluorescence lifetime of the donor (τd) is the average time that it remains in its first excited state before fluorescing. This value is directly correlated with fd. Fluorescence lifetime (τd) was determined using the Strickler–Berg equation. Using this equation, a good agreement has been achieved between lifetimes that were theoretically and experimentally evaluated [16]. Therefore, the calculated fluorescence lifetime of τd = 2.8 ns is a convenient measurement.

As seen in Fig. 4 that there is a strong overlap between the absorption band of Q1(0,0) and the fluorescence spectrum of ZnPc(COONa)4. As a result, the overlap integral for Förster energy transfer to take place should have a considerable value [1–8]. Accordingly, it was concluded that homo-FRET might occur to permit radiationless intermolecular hopping of energy from an originally excited Pc-donor to other ground state Pc-acceptor. An energy transfer mechanism from Pc as a donor to Pc as an acceptor is favorable because the energy of the first excited singlet state of Pc-donor is energetically equal to that of the singlet state of Pc-acceptor.

Fig. 4.

Vertical lines represent the overlap between absorption and fluorescence spectra of ZnPc(COONa)4

The most important parameter affecting the resonance energy transfer is Förster radius (R 0), at which the energy transfer probability from donor to acceptor is Pda = 50% [1–5]. Therefore, there is an identical probability for the occurrence of resonance energy transfer and fluorescence emission. The Förster radius is given by [1–7]:

| 3 |

where fd is the fluorescence quantum yield of donor in the absence of the acceptor (quencher), n is the index of refraction of the solvent (n = 1.33 for water), and κ2 is the orientation factor describing the relative transition dipole moments of the donor and acceptor ranging between −2 and 2 [23]. Its average value is given by 2/3 in a solution when the donor and acceptor rotate rapidly during the lifetime of the excited donor, and therefore the polarization is randomized during the energy transfer [1–4]. J is the normalized spectral overlap integral of the donor–acceptor pair, which is given by [10]:

| 4 |

where If(λ) represents the corrected emission intensity of the donor from λ to λ + dλ and ε(λ) is the molar absorbance of Pc at wavelength of λ.

Applying Eqs. (3) and (4) along with the experimental data, the Förster radius for dipole-dipole FRET of ZnPc(COONa)4 molecule was estimated as 42 Å. This value is within the typical range for those of the aromatic molecules, which are between 10 and 100 Å [9–11]. The significance of obtaining the Förster radius is that it can be used as a spectroscopic molecular ruler to detect any change of the distance between the donor and acceptor [24].

The occurrence of FRET may cause a reduction in the intersystem crossing quantum yield, and consequently a decrease in the singlet oxygen quantum yield. The low singlet oxygen quantum yield is undesirable in the applications of photodynamic therapy of cancer [25, 26].

Förster showed that the probability of the FRET process (Pda) depends on the inverse sixth power of the donor–acceptor distance and is given by [4–8]:

| 5 |

where rda is the center-to-center position vector between the molecule dipole moments of the donor and acceptor. The energy transfer probability was plotted against the distance of donor–acceptor pair (rda) (Fig. 5) applying Eq. (5). As shown, the probability of energy transfer decreases with increasing of donor–acceptor distance and practically is negligible at a distance larger than 100 Å. Therefore, to prohibit the dipole–dipole interaction, the distance between the molecules should be larger than this value. Moreover, at distances of rda < 23 Å the probability of energy transfer reaches about unity (see Fig. 5). There is almost no deactivation process other than that of the energy transfer. Nevertheless, this may not be the case, since dimer and/or higher aggregation could also be formed at rda < 23 Å where the molecules’ concentration is high. This will also result in a fluorescence quenching. In vivo, aggregation may be formed where the drug has tendency to accumulate in the target tissue [27].

Fig. 5.

Dependence of the energy transfer probability on the distance of donor–acceptor pair (r da) according to Förster’s theory

The energy transfer probability in Eq. (5) has an inflexion point at rda = R0 = 42 Å as shown in Fig. 5. For a distance of rda < 42/2 Å, Pda is close to one (Pda = 98.4%) and the curve becomes flat. For rda > 2 × 42 Å, it comes close to zero (Pda = 1.6%) and the curve starts to become flat. Thus, the dynamic range corresponds to 0.5 × 42 Å < rda < 2 × 42 Å. Furthermore, the maximum probability in Fig. 5 is reached more abruptly than its minimum. Accordingly, longer distances could be evaluated to some extent more accurately than shorter distances. For this reason, the FRET can be utilized as a sensitive spectroscopic ruler for the evaluation of a long-range distance in biology [28]. The strong distance-dependence of FRET has been widely utilized in studying biological systems such as the structure and dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids.

The efficacy of a drug decreases when intermolecular or intramolecular energy transfer occurs [29]. As a rule, this happens if the acceptor concentration is high. The critical concentration of Pc-acceptor can be calculated by [Pc] = , [11] where R 0 is in Å. At this concentration, the probability of energy transfer is 76% [5]. From Eq. (5), the distance for this probability can be obtained as 34.7 Å, which is slightly less than the Förster radius of 42 Å. Therefore, the concentration of acceptor to minimize the intermolecular transfer probability should be much lower than [11]. Consequently, the critical concentration of the acceptor is [Pc] = 6 mM. At this concentration, the average distance between molecules can be calculated to be 80.8 Å. According to Eq. (5), the probability at this distance is 2%. This value is very small, and hence it is reasonable to apply () as a limit to obtain the concentration where energy transfer probability approximately vanishes

Diffusion can also increase the energy transfer probability [10]. By inserting the Pc radius of 8.5 Å (obtained by ArgusLab) [22] and water viscosity of 0.001002 Pa.s at 20 °C in the Stokes–Einstein equation [10], one obtains the diffusion coefficient of D = –2.52 × 10−6 cm2/s. The substitution of this value together with the donor lifetime into the relationship of [10] results in the diffusion distance as Δx= 119 Å. The Pc concentration in the current study is 6 μM. At this concentration, the average distance between Pc molecules is about 808 Å. This distance is nearly seven times larger than the diffusion limit and almost 19 times larger than the Förster radius. Therefore, it was deduced that the addition of micromolar amounts of Pc molecules in a solution could not lead to an efficient occurrence of self-energy transfer.

Collisions between an excited-state fluorophore and other molecules occasionally quench the fluorophore, such as a formation of dimer and/or higher aggregation. This process requires proximity between the fluorophore and quencher. In this case, confusion may arise due to the difficult differentiation between the occurrence of encounter collision and energy transfer. In order to observe collisional quenching, the diffusion-controlled bimolecular rate constant must be determined (kq), which can be calculated by [10]:

| 6 |

where Na is Avogadro’s number. The collision radii of quencher and fluorophore are Rq = 8.5 Å and Rf = 8.5 Å, respectively. Moreover, the diffusion coefficients of the quencher and fluorophore are Dq = 2.52 × 10−6 cm2/s and Df = 2.52 × 10−6 cm2/s, respectively. The insertion of these parameters into Eq. (6) produces kq = 6.5 × 109 M−1s−1. Therefore, the collisional frequency (Fc) when the quencher concentration equals [Pc] = 6 μM is Fc = 39 × 103 s−1 according to Eq. (7):

| 7 |

This value is very small and cannot compete with the process of resonance energy transfer where the deactivation rate has the order of 109-1011 s−1 as will be discussed later. Furthermore, the small value of the collisional frequency could not lead to the formation of a dimer by collision. Hence, Pc fluorescence is only dissipated by the mechanism of energy transfer.

If the appropriate acceptor is close to the donor, the fluorescence lifetime of the donor decreases because of FRET to the acceptor. Based on the calculated probability of FRET, the lifetime of the donor in the presence of the acceptor (τda) was calculated [10]:

| 8 |

Figure 6 shows dependence of the calculated value of τda on donor–acceptor distance. Taking into account that the rotation of molecules in aqueous media is rapid and complete in three dimensions, the minimum contact distance of the donor–acceptor pair can be considered to be rda = 17 Å (rda = Rq + Rf). Consequently, at a contact distance of rda = 17 Å the fluorescence lifetime is τda = 12 × 10−12 s. Based on this, there is an effective energy transfer and most donor molecules are involved in this process. For a distance of rda < 17 Å, the FRET mechanism might not be efficient owing to the fact that at very close distance the multipole and electron exchange interactions can also cause energy transfer [30, 31]. For that reason, the donor fluorescence should be entirely quenched.

Fig. 6.

Dependence of the calculated fluorescence lifetime (τda) on the donor–acceptor distance (r da)

Using Förster theory, the energy transfer rate (kda) can be calculated according to the following expression [10]:

| 9 |

The energy transfer rate was plotted against the distance of donor–acceptor pair as depicted in Fig. 7. As can be seen, at a distance of 17 Å the energy transfer rate is = 5.4 × 1010 s−1, which is three orders of magnitude higher than the other deactivation rate constants of fluorescence (kf = 3.6 × 107 s−1) [32], internal conversion (kic = 1.9 × 108 s−1) [32], and intersystem crossing (kisc = 1.3 × 108 s−1) [32]. Thus, the fluorescence quenching by energy transfer is very efficient at that distance. Based on this, the excitation energy stays about = 19 ps at the initially excited donor before hopping to the acceptor. At a distance of 100 Å, the energy transfer rate is kda = 1.3 × 106 s−1, which is only 0.37% of all other dissipation processes (kf + kic + kisc). This means that it is reasonable to neglect the influence of FRET at distances larger than 100 Å. An abrupt decrease in the energy transfer takes place when the distance between the acceptor and donor changes from 17 to 30 Å, which is due to the fact that the Förster energy transfer rate decreases with (see Eq. 9). In fact, FRET probability falls dramatically as the distance between the donor and acceptor exceeds the Förster length, making FRET a significant method for the investigation of various biological phenomena in which tracing physical proximity is necessary.

Fig. 7.

The energy transfer rate (k da) versus the distance of donor–acceptor pair (r da)

Conclusions

Resonance energy transfer process plays an important role in the photochemistry and photophysics of several types of systems including biological system. Energy transfer process from ZnPc(COONa)4 as a donor to ZnPc(COONa)4 as an acceptor is energetically favorable due to the same energy of their first excited singlet states. The overlap between the donor emission spectrum and acceptor absorption spectrum is large. Accordingly, FRET occurs from donor to acceptor. Using VIS absorption and emission spectral experimental data, the Förster distance for ZnPc(COONa)4 molecule was calculated to be R0 = 42 Å (typically in the range of 20–60 Å). Calculations have shown that the collisional quenching did not play a role in fluorescence quenching at the considered concentration, but the only process responsible for this quenching is FRET. It was shown that that the energy transfer is a sensitive spectroscopic ruler for determination of the distance between the donor and acceptor.

References

- 1.Lakowicz, J.R.: Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd edn. Plenum Press, New York (1999)

- 2.Kasha M. Energy transfer mechanisms and the molecular exciton model for molecular aggregates. Radiat. Res. 1963;20:55–71. doi: 10.2307/3571331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Förster T. Intermolecular energy migration and fluorescence. Ann. Phys. 1948;2:55–75. doi: 10.1002/andp.19484370105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turro, N.J.: Modern Molecular Photochemistry. Benjamin Cummings, Menlo Park, CA (1987)

- 5.Lakowicz, J.R.: Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 1st edn. Plenum Press, New York (1983)

- 6.Andrews, D.L., Demidov, A.A.: Resonance Energy Transfer. Wiley, Chichester (1999)

- 7.Valeur B. Molecular fluorescence: principles and applications. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wehry, E.L.: Modern Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Plenum Press, New York (1976)

- 9.Clegg, R.M.: Förster resonance energy transfer–FRET what it is, why do it, and how it’s done. Lab. Tech. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 1–58 (2009)

- 10.Lakowicz, J.R.: Principles of Fluorescent Spectroscopy, 3rd edn. Springer, New York (2006)

- 11.Wu P, Brand L. Resonance energy transfer: methods and applications. Anal. Biochem. 1994;218:1–13. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiker, J.D., Bommer, J.C.: Chlorophyll and related pigments as photosensitizers in biology and medicine. In Chlorophyll, ed. H. Scheer. CRC Press, Florida (1991)

- 13.Al-Omari S, Alghezawi N, Al-Noaimi M, Al-Hamarneh IF, Marashdeh M. Observation on symmetry properties of sodium zinc(II)-2,9,16,23-phthalocyanine tetracarboxylate in water:NaOH solution. J. Fluoresc. 2014;24:835–9. doi: 10.1007/s10895-014-1359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Omari S. Toward a molecular understanding of the photosensitizer-copper interaction for tumor destruction. Biophys. Rev. 2013;5:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s12551-013-0112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Omari S, Ali A. Photodynamic activity of pyropheophorbide methyl ester and pyropheophorbide a in dimethylformamide solution. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2009;28:70–77. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2009_01_70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strickler SJ, Berg RA. Relationship between absorption intensity and fluorescence lifetime of molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1962;37:814–22. doi: 10.1063/1.1733166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacıvelioğlu F, Durmus M, Yesilot S, Gürek AG, Kılıç A, Ahsen V. Synthesis, electronic absorption and fluorescence spectral properties of phenoxycyclotriphosphazene-substituted phthalocyanines. Dyes Pigments. 2008;79:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2007.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iglesias RS, Segala M, Nicolau M, Cabezo B. Computational study of the geometry and electronic structure of triazolephthalocyanines. J. Mater. Chem. 2002;12:1256–1261. doi: 10.1039/b107790m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessel D, Dougherty T. Porphyrin photosensitization. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKeown NB. Phthalocyanine materials: synthesis, structure and function. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadish, K.M., Smith, K.M., Guilard, R.: The Porphyrin Handbook. Academic Press, Boston (1999)

- 22.ArgusLab (tm) (2004) Program package. Version 4.0, Planaria Software LLC

- 23.Müller, S., Galliardt, H., Schneider, J., Barisas, B.G., Seide, T.: Quantification of Förster resonance energy transfer by monitoring sensitized emission in living plant cells. Front. Plant. Sci. 4, 413–20 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Stryer L. Fluorescence energy transfer as a ruler. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1978;47:819–846. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.004131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Omari S. Separation of static and dynamic thermodynamic parameters for the interaction between pyropheophorbide methyl ester and copper. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2014;18:297–304. doi: 10.1142/S1088424614500023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Omari S. Modeling the concentrations and efficiencies for the interacting species of pyropheophorbide methyl ester-copper association. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 2013;8:73–87. doi: 10.1142/S1793048013500045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonacucina G, Cespi M, Mencarelli G, Giorgioni G, Palmieri GF. Thermosensitive self-assembling block copolymers as drug delivery systems. Polymers. 2011;3:779–811. doi: 10.3390/polym3020779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hink MA, Bisseling T, Visser AJ. Imaging protein–protein interactions in living plant cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002;50:871–883. doi: 10.1023/A:1021282619035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heyduk T, Heyduk E. Molecular beacons for detecting DNA binding proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:171–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kavarnos, G.J.: Fundamentals of Photoinduced Electron Transfer. VCH Publishers Inc, USA. (1993)

- 31.Simpson WT, Peterson DL. Coupling strength for resonance force transfer of electronic energy in Van der Waals solids. J. Chem. Phys. 1957;26:588–593. doi: 10.1063/1.1743351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Omari, S.: Kinetic model for the molecular system of zinc(II)-2,9,16,23-phthalocyanine tetracarboxylate. J. Nonlinear. Optic. Phys. Mat. 24, 1550005 (2015)