Abstract

Clostridium sporogenes is a non-pathogenic close relative and surrogate for Group I (proteolytic) neurotoxin-producing Clostridium botulinum strains. The exosporium, the sac-like outermost layer of spores of these species, is likely to contribute to adhesion, dissemination, and virulence. A paracrystalline array, hairy nap, and several appendages were detected in the exosporium of C. sporogenes strain NCIMB 701792 by EM and AFM. The protein composition of purified exosporium was explored by LC-MS/MS of tryptic peptides from major individual SDS-PAGE-separated protein bands, and from bulk exosporium. Two high molecular weight protein bands both contained the same protein with a collagen-like repeat domain, the probable constituent of the hairy nap, as well as cysteine-rich proteins CsxA and CsxB. A third cysteine-rich protein (CsxC) was also identified. These three proteins are also encoded in C. botulinum Prevot 594, and homologues (75–100% amino acid identity) are encoded in many other Group I strains. This work provides the first insight into the likely composition and organization of the exosporium of Group I C. botulinum spores.

Keywords: Spore appendages, Two dimensional crystals, Cysteine rich proteins

Highlights

-

•

Clostridium sporogenes spores have a paracrystalline outer surface (exosporium).

-

•

The spore surface is decorated with a variety of filaments and appendages.

-

•

Appendages include long beaded filaments of unknown function.

-

•

BclA-like exosporium proteins with collagen-like repeat domains are present.

-

•

Novel cysteine-rich exosporium proteins may compose the exosporium basal array.

1. Introduction

Endospores are produced by Bacillus and Clostridium spp; their extreme resistance properties contribute to their persistence and dissemination in the environment. A cellular core is surrounded by a thick layer of peptidoglycan cortex, a proteinaceous spore coat, and in many cases a looser outermost layer, the exosporium.

The only exosporium layer studied in detail is that of Bacillus anthracis spores and the spores of the closely related Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis, where it contains an outer hairy nap and a paracrystalline basal layer with hexagonal arrays (Stewart, 2015). The BclA glycoprotein of B. anthracis, which contains a collagen-like repeat (CLR) domain, is the major contributor to the hairy nap layer of the exosporium (Sylvestre et al., 2003). This protein is likely to be involved in adherence and entry into the host (Xue et al., 2011) and influences spore surface properties (Lequette et al., 2011). A second CLR-containing glycoprotein BclB is also present in B. anthracis exosporium (Thompson et al., 2012). The cysteine-rich ExsY protein is essential for the formation of exosporium (Boydston et al., 2006, Johnson et al., 2006).

There is little information on the exosporium of Clostridia, with the recent exception of Clostridium difficile. In that species a BclA-like protein, BclA1, is present and a cysteine-rich protein, CdeC, is required for morphogenesis of the coat and of an exosporium layer (Paredes-Sabja et al., 2014).

Clostridium botulinum is responsible for major food poisoning by producing lethal neurotoxin (Peck et al., 2011) and is classified as a potential bioterror agent. It is essential to understand the structure and composition of spore surface layers, to underpin development of detection and inactivation regimes. As yet, only limited information is available for C. botulinum exosporium. For example, the exosporium of proteolytic C. botulinum type A strain 190L demonstrates a hexagonal array (Masuda et al., 1980) and is resistant to urea, DTT, SDS and proteolytic enzymes (Takumi et al., 1979). For practical reasons, we have chosen to study Clostridium sporogenes, a non-pathogenic and widely used surrogate for Group I (proteolytic) C. botulinum (Peck et al., 2011). A recent phylogenetic analysis, using complete and unfinished whole genome sequences (Weigand et al., 2015), shows that within C. botulinum Group I, a major cluster of strains (including Hall, Langeland and Loch Maree) can be distinguished from the major C. sporogenes cluster, which itself does include some C. botulinum toxigenic strains, such as Prevot 1662, Prevot 594 (Smith et al., 2015), Osaka 05 and ATCC 51387. C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792 (NCDO 1792), the subject of this study, has been included in a microarray study of genome relatedness within C. botulinum Group I and C. sporogenes strains (Carter and Peck, 2015), and we have found the exosporium of this C. sporogenes strain amenable to proteomic and structural analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains, growth conditions and media

C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792 (NCDO 1792) was grown on BHIS (Brain heart infusion supplemented with 0.1% l-cysteine and 5 mg/ml yeast extract) agar as previously described in (Smith et al., 1981) and incubated at 37 °C overnight in an anaerobic chamber with 10% H2, 10% CO2 and 80% N2.

2.2. Spore preparation and harvest

A single colony from BHIS agar was inoculated into TGY (Tryptose glucose yeast extract) broth. After overnight growth at 37 °C, 1.5 ml was added to 15 ml of SMC (Sporulation medium) broth (Permpoonpattana et al., 2011), and grown to an OD600 of 0.4–0.7. Aliquots (0.1 ml) were spread on SMC agar, and incubated at 37 °C for 1 week. Spores from the agar surface were harvested by resuspension in 3 ml ice-cold sterile distilled water, and water-washed 10 times to remove vegetative cells and debris, then separated from remaining vegetative cells by gradient centrifugation in 20%–50% Histodenz™ (Sigma). The spores were washed twice as above with water to remove the Histodenz™. Preparations (>99% free spores) were stored in sterile distilled water at 4 °C.

2.3. Exosporium preparation

Spores were diluted in spore resuspension buffer (SRB) (50 mM Tris HCl pH-7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF) to 80 ml at OD600 of 2–3, French pressed twice at 16,000 psi, and the suspension centrifuged at 10,000 xg for 15 min to pellet the spores. The supernatant was reserved, and pellets were washed twice more in SRB. All supernatants were pooled and concentrated to 3 ml using centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius, 10 kDa cutoff). Concentrated exosporium was diluted with 4 vol of 20% urografin R-370 (Schering), layered onto 50% urografin, and centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 30 min. The top yellow layer containing the exosporium was collected, dialysed against water, and centrifuged at 100,000 xg for 2 h; the pellet containing the purified exosporium fragments was resuspended in 0.5 ml SRB and stored at −20 °C.

2.4. Salt and SDS wash of the exosporium fragments

Exosporium fragments purified as described in Section 2.3 were washed sequentially in exosporium wash buffers, using high salt and then SDS to remove loosely associated proteins. These washes, modified from Todd et al. (2003), were 1: 50 mM Tris pH-7.5, 0.5 M KCl, 0.25 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% glycerol and 1 mM PMSF; 2: 1 M NaCl; 3: 50 mM Tris pH-7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS and 1 mM PMSF and 4: 50 mM Tris pH-7.5, 10 mM EDTA and 1 mM PMSF (to remove SDS). Each wash was centrifuged at 100,000 xg for 2 h. Washes 3 and 4 were repeated. The final pellet (washed exosporium) was resuspended in 500 μl of 50 mM Tris pH-7.5, 10 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF, passed through a 21G needle several times and stored at −20 °C.

2.5. Sonication to release exosporium fragments

Spores diluted in SRB were sonicated for 20 cycles of 15 s with 15 s cooling and then centrifuged at 1000 xg for 10 min to pellet the spores. The supernatants containing exosporium fragments were used for EM studies.

2.6. Protein concentration determination

Protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay (Pierce).

2.7. Gel electrophoresis of exosporium proteins

Aliquots (15–53 μg) of washed exosporium were vacuum dried at 30 °C for 20 min, then resuspended in 15 μl of urea solubilisation buffer (25 mM Tris pH-8, 8 M urea, 500 mM NaCl, 4 M DTT & 10% SDS) and heated at 95 °C for 20 min. After addition of 5 μl of 4X LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen), the sample was loaded on a 4–12% gradient NuPAGE Bis-Tris pre-cast SDS gel (Invitrogen), with MOPS running buffer. Gels were stained with SYPRO Ruby, visualized under UV, then further stained with Coomassie blue R-250.

2.8. Identification of exosporium proteins

2.8.1. Proteins in major bands from SDS-PAGE

Samples (1.5 mm diameter), excised from selected gel bands, were digested with trypsin following cysteine derivatisation; peptides were analysed by nano-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Protein identification was from a database containing 7995 C. sporogenes sequences downloaded from UniProtKB. The detailed protocol is described in SI-1.

2.8.2. Protein extraction directly from bulk exosporium

Proteins solubilized from washed exosporium by incubation in 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 12 mM N-lauroylsarcosine and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate were trypsin digested after cysteine derivatisation, subjected to nano-LC-MS/MS analysis, and protein identified as for the gel-bands. The detailed protocol is described in SI-2.

2.9. Electron microscopy (EM)

Diluted whole spores or purified exosporium (3 μl) were applied to glow discharged carbon-coated Cu/Pd grids; after 1 min the grid was blotted, washed once with (0.75%) uranyl formate and then stained for 20 s. Excess stain was removed by blotting followed by vacuum drying and the grid examined in a Philips CM100 electron microscope operating at 100 kV. Images were recorded on a Gatan MultiScan 794 1 k × 1 k CCD camera at between 3000 and 52,000× magnification and 500–1200 nm underfocus. 10 length measurements from hairy nap, and other filaments were taken and the mean values with standard deviations are shown in the data.

2.10. Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

A suspension of exosporium fragments (Section 2.4) was incubated on freshly cleaved mica (Agar Scientific) for 20 min, then washed with 10 × 1 ml of HPLC grade water (Sigma Aldrich). Samples imaged in water were used without further preparation; samples imaged in air were blown dry with filtered nitrogen. Imaging in water was performed using a Dimension FastScan AFM (Bruker) and FastScan D probes (nominal force constant and resonant frequency 0.25 N/m and 110 kHz in water, respectively) in tapping mode with a free amplitude of approximately 1.2 nm and a set point of 80–90% of this value. Imaging in air was performed using a Multimode (Bruker) or NanoWizard® 3 (JPK) AFM in tapping mode using TESPA probes (Bruker) with a nominal force constant and resonant frequency of 40 N/m and 320 kHz, respectively. The free amplitude was approximately 8 nm and images were acquired with a set point 90–95%. In both environments, the feedback gains, scan rate, set point and Z range were adjusted for optimal image quality while scanning. Height and phase images were acquired simultaneously and processed (cropping, flattening, plane fitting) using NanoScope Analysis or JPK DP software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. C. sporogenes spore surface features revealed by EM

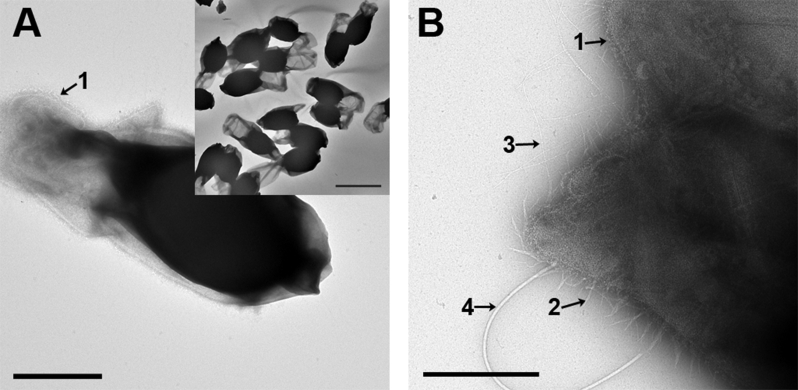

The spores of C. sporogenes (Fig. 1) are enveloped by an exosporium that is more extended at one pole. The exosporium has a ‘hairy nap’ that appears uniform (30 ± 5 nm deep) along the perimeter of the exosporium when viewed in projection, so we infer that it covers the entire surface (Fig. 1A). At higher magnification (Fig. 1B), other features of the exosporium surface become visible including the hair-like nap (arrow 1) and intermediate fibrils (arrow 2). In addition, beaded fibrils, which display a regular pattern of bead-like structures along their length (arrow 3; clearly visible in higher magnification in Fig. 2B and C), and a large appendage up to 1–2 μm long with a diameter of 20 nm (arrow 4) are present on the spore surface.

Fig. 1.

Negative stain electron microscopy of whole spores and fragments of the exosporium of C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792. A. A whole spore, showing the electron-dense core with the folded sac-like exosporium extended at one pole. Scale bar, 0.5 μm. A ‘hairy nap’ is present on the surface of the exosporium (arrow 1). Inset shows a lower magnification, wider view. Scale bar, 2 μm. B. High magnification image of part of a whole spore edge showing an area of exosporium with various surface features labeled: 1, hairy nap; 2, intermediate fibril; 3, beaded fibril; 4, large appendage. Scale bar, 0.5 μm.

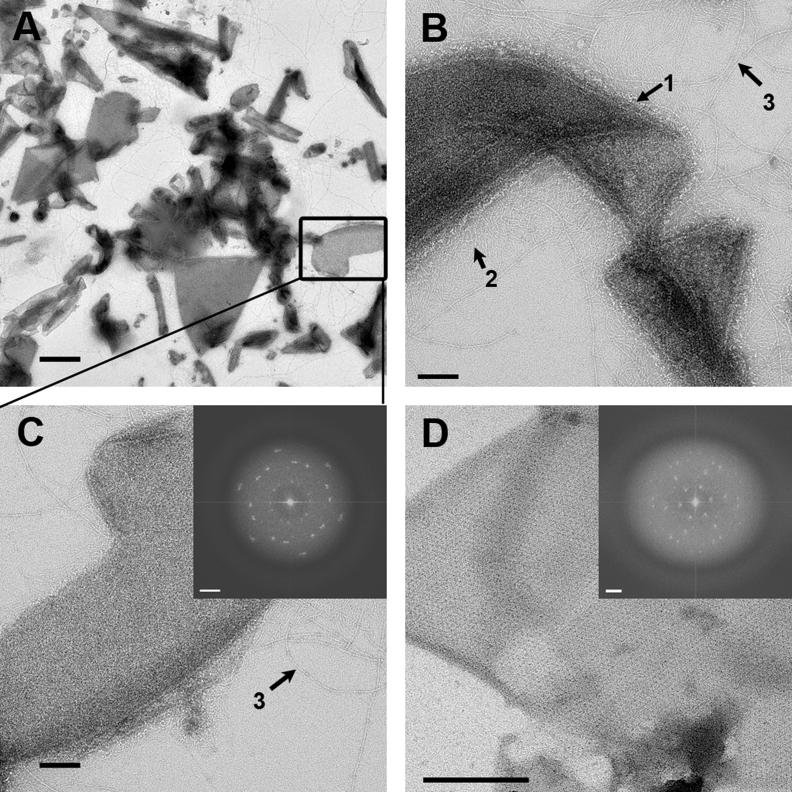

Fig. 2.

Negative stain electron microscopy of purified fragments of exosporium. A. Fragments of exosporium produced by French press, followed by a series of salt and SDS washes. The box indicates the fragment magnified in Fig. 2C. Scale bar, 0.5 μm. B. Hairy nap (1), intermediate fibrils (2) and beaded fibrils (3) are visible on the surface of an exosporium fragment. Scale bar, 100 nm. C. Magnified, boxed area from Fig. 2A; a hairy nap is visible all along the perimeter, suggesting that the entire surface is covered. It also shows an attached beaded fibril (3). Scale bar, 100 nm. Inset shows a Fourier transform from an area of the image. Scale bar, 0.104 nm−1. D. Fragment of unwashed exosporium produced by the sonication method. It reveals a well-contrasted and well-ordered hexagonal lattice. There is no indication of any hairy nap on this fragment. Scale bar, 200 nm. Inset shows a Fourier transform from an area of the image. Scale bar, 0.104 nm−1.

3.2. Surface features of exosporium fragments revealed by EM

EM analysis of purified, washed exosporium confirmed the presence of highly enriched exosporium fragments (Fig. 2A). A higher magnification view is shown in Fig. 2B and C. The fragments tend to fold, revealing surface features clearly at the fold perimeter, including a hairy nap (arrow 1), intermediate fibrils approximately 80–200 nm long (arrow 2), and beaded fibrils up to 1–2 μm long (arrow 3, Fig. 2B). Most fragments showed an underlying ordered crystal lattice (insets, Fig. 2C and D). In a small proportion (10%) of fragments of sonicated exosporium, the lattice showed sufficient contrast that it could be clearly discerned by eye (Fig. 2D); in these cases the hairy nap was detached and there was less disordered background. Fig. 3A shows more detail of the beaded fibrils with ‘beads’ at regular intervals of 70 ± 2 nm (arrow 3). The diameter across the fibril and beaded area is 6 ± 1 nm and 11 ± 1 nm, respectively. It is unclear whether the beaded fibrils and large appendages emanate directly from the exosporium or from deeper within the spore. However, it is clear that they can remain associated with the exosporium when fragmented.

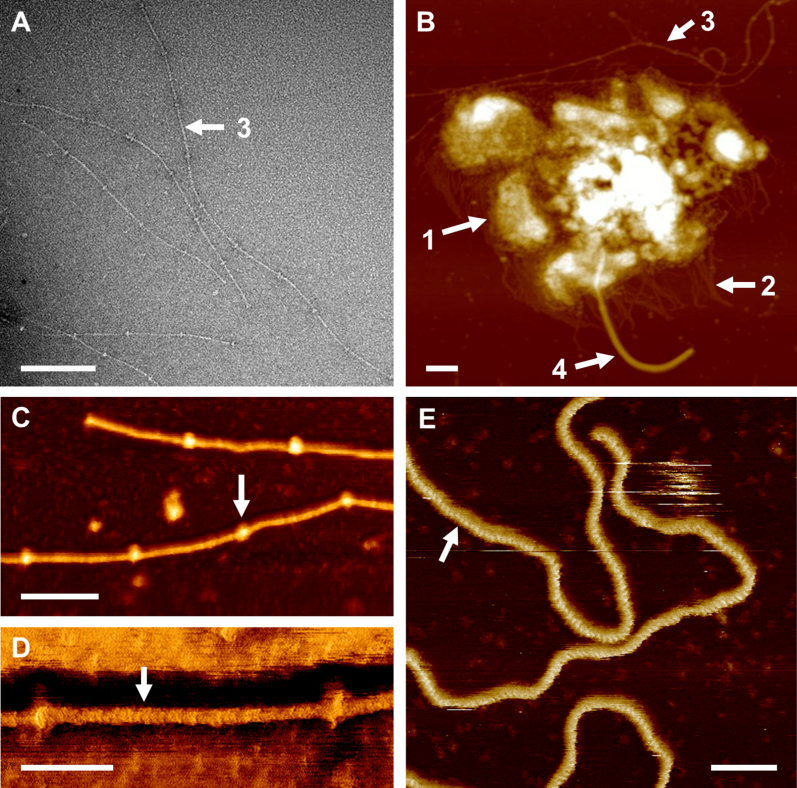

Fig. 3.

Surface decorations of the exosporium. A. A high magnification negative stain electron micrograph of washed exosporium shows a beaded fibril with regular bead-like repeats at approximately 70 nm intervals. Scale bar, 100 nm. B. AFM height image of a fragment of washed exosporium. Four different surface features are indicated by white arrows with numbering: 1, hairy nap; 2, intermediate fibril; 3, beaded fibril; 4, a large appendage. The image was recorded in tapping mode in air. Dark to bright variation corresponds to a height of 30 nm. Scale bar, 100 nm. C. AFM height image recorded as in (B) shows beaded fibril with the beads (arrow). The distance between two beads is approximately 70 nm; dark to bright variation in height is 4.5 nm. Scale bar 50 nm. D. Cropped region of the AFM phase image recorded simultaneously with the height image shown in C, shows internal repeats of approximately 2 nm in the beaded fibril (arrow). Dark to bright variation in phase is 10.8°. Scale bar 20 nm. E. AFM height image taken in tapping mode in water shows beaded fibrils with internal repeats of approximately 2 nm (arrow). The beads observed in tapping mode in air were not observed in water. Dark to bright variation in height is 4.36 nm. Scale bar 20 nm.

3.3. Surface features of exosporium fragments and appendages revealed by AFM

An AFM image of exosporium fragments in air shows a nap-like fringe, approximately 20–30 nm deep (Fig. 3B; arrow 1), on the spore surface. Other appendages include (i) intermediate fibrils ca. 80–200 nm in length (Fig. 3B; arrow 2) and (ii) beaded fibrils, punctuated with ‘bead-like’ elements (Fig. 3B, C and D; arrow 3) at an average interval of 68 ± 2 nm. There is a shorter periodic feature (repeat of 1.9 ± 0.2 nm) on the fibril, shown in Fig. 3D. The measured height and width of the beaded fibril in air is approximately 2 nm and 8 nm, respectively, and of the beaded area 3 nm and 14 nm, respectively (Fig. 3D). We also saw the approximate 2 nm repeat (2.0 ± 0.2 nm) when fibrils were imaged in water (Fig. 3E). However, we found no evidence of the regular ‘beads’. It is possible that the beads arise through some contractile mechanism upon dehydration, as they are also seen under negative stain EM. In addition, a large appendage, with height 6–9 nm, width 20–30 nm and up to 1–2 μm long, is seen on the surface of the exosporium (Fig. 3B; arrow 4). When measured with AFM the height and width of these appendages are significantly smaller and larger (respectively) than the diameter measured by EM. We attribute these effects to convolution of the fibril with the imaging tip; this has been shown to significantly increase the measured width and reduce the measured height when imaging features that are comparable in size, or smaller than, the length scale of the tip-surface interaction area. This effect has been shown to be particularly prevalent when imaging isolated structures on otherwise flat surfaces (Santos et al., 2011).

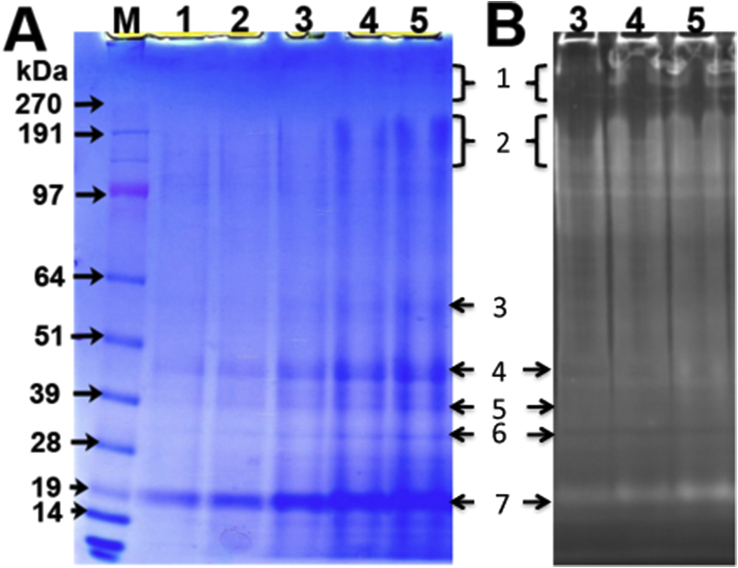

3.4. C. sporogenes exosporium protein profiles

Exosporium fragments (Section 2.3) were dried and resuspended in a denaturing buffer containing 8 M urea, 4 M DTT and 10% SDS and heated (Section 2.7) before separation of proteins by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S1). Six of the most strongly stained bands were excised for further analysis. In order to remove loosely attached or contaminating proteins, these exosporium fragments were further subjected to high salt and SDS washes (Section 2.4), then resuspended and heated as above before separation on SDS-PAGE. The protein profile of washed exosporium fragments (Fig. 4A) contained bands ranging from <19 kDa to >190 kDa. The region above 190 kDa was poorly stained by Coomassie, but material at 200 to >300 kDa was clearly visible on the SYPRO Ruby stained gel (Fig. 4B). A significant proportion of the material remained in high molecular weight species, despite the harsh solubilisation conditions. The smeared regions (>200 kDa) at the top of the gel (band 1) and from 150 to 200 kDa (band 2) along with 5 smaller individual bands (bands 3–7) were excised for protein identification.

Fig. 4.

Protein profile of salt and SDS washed exosporium. A. Aliquots (15–53 μg) of washed exosporium were vacuum dried, resuspended in 15 μl of solubilisation buffer (25 mM Tris pH-8, 8 M urea, 500 mM NaCl, 4 M DTT, 10% SDS) and boiled at 95 °C for 20 min, loaded on 4–12% gradient (NuPAGE) gel and resolved with MOPS buffer. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The marked bands (1–7) were excised and proteins identified by LC-MS/MS. Lane M, protein marker, lane 1,12.5 μg; lane 2, 25 μg; lane 3, 32.5 μg; lane 4, 45 μg and lane 5, 52.5 μg of exosporium protein loaded. B. The gel shown in Fig. 4A (lanes 3–5) was stained with SYPRO Ruby and visualized by ultraviolet light. Bands above 191 kDa are clearly visible (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. Identification of proteins from excised gel bands

Proteins were analysed by LC-MS/MS of trypsin digests (Section 2.8.1). As the genome sequence of strain C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792 is not available, the identifications were made using proteins of C. sporogenes strains PA 3679 (Bradbury et al., 2012) and ATCC 15579 in the UniProtKB database (The Uniprot consortium, 2011).

Major proteins identified from unwashed exosporium include likely soluble proteins which may be loosely associated, such as GroEL and several enzymes, and also a protein containing multiple 24 amino acid repeats, highly conserved in C. botulinum Group I. The protein IDs, and sequences and peptide identifications, are shown in Table 1 and SI-3.

Table 1.

Selected C. sporogenes proteins identified by LC-MS/MS analysis from bulk washed exosporium, and from SDS PAGE-separated proteins from washed and unwashed exosporium.

| UniProtKB ID | MW (kDa) | Protein | Proteins identified from |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washed exosporium gel bands-Fig. 4 & SI-1 | Bulk washed exosporium-ID number in SI-2 | Unwashed exosporium gel bands-Fig. S1 & Sl-3 | |||

| G9F2G0 | 33.4 | CsxA (25 cys) | band 1 | ID 1 | |

| J7T0S1 | 16.6 | CsxB (10 cys) | band 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 & 7 | ID 58 | |

| G9F2F5 | 17.1 | BclA fragment | band 1 & 2 | ID 59 | |

| G9F2J8 | 56.7 | Stage ΙV A sporulation protein | band 3 | ID 63 | |

| G9EZ29 | 59.5 | LysM domain containing protein | band 3 | ||

| G9F4A5 | 68.4 | Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase | band 3 | ID 60 | |

| G9F1L8 | 44.9 | Aminotransferase class I/II | band 4 & 5 | ||

| G9EWK8 | 43.4 | Elongation factor Tu | band 4 | ||

| J7TAJ5 | 45.6 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | band 4 | ID 16 | band 4 |

| G9EYX8 | 46.5 | Arginine deiminase | band 4 | ID 15 | |

| J7SU99 | 36.4 | Proline racemase | band 5 | ID 68 | band 6 |

| J7T8Q8 | 35.7 | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase | band 5 | ID 36 | band 5 |

| J7SXJ9 | 39.9 | Pyruvate/ferridoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase | band 5 | ||

| J7SW79 | 42.5 | CotS | band 5 | ||

| J7SGD1 | 21.4 | Uncharacterised CotJC homologue | band 5 & 6 | ID 67 | |

| G9EW59 | 30 | CsxC (14 cys) | band 6 | ID 66 | |

| G9EW78 | 21.3 | CotJC | band 6 | ID 64 | |

| G9EW77 | 11.1 | Spore coat peptide assembly protein CotJB | band 6 | ID 65 | |

| G9EWA8 | 35.4 | NIpC/P60 family protein | band 6 | ||

| G9F4H9 | 23.8 | BclB | ID 45 | ||

| J7T3Q4 | 6.6 | Uncharacterised (4 cys) | ID 51 | ||

| G9EYZ3 | 44.4 | Uncharacterised (7 cys) | ID 28 | ||

| G9EWT5 | 21.3 | Uncharacterised (7 cys) | ID 31 | ||

| G9EWH5 | 8.4 | Uncharacterised (12 cys) | ID 55 | ||

| G9F5J7 | 34.4 | Stage III sporulation protein | ID 18 | ||

| J7TET6 | 26 | Uncharacterised protein | ID 50 | ||

| G9EZQ2 | 60 | Chaperonin GroEL | ID 62 | band 3 | |

| G9F301 | 67.9 | Peptidase M24 | ID 37 | band 2 | |

The major proteins in 7 bands excised from the SDS-PAGE gel of washed exosporium were identified. Protein IDs are shown in Table 1 and sequences and peptide identifications are presented in SI-2. The very high molecular weight region (band 1) contained a 299 residue (25 cysteine) protein, which we named CsxA, (for C. sporogenes exosporium protein A) and a protein with a characteristic collagen-like repeat (CLR) domain as in B. anthracis BclA, which we named BclA by analogy; apart from the CLR domain, it is not a homologue of B. anthracis BclA. Band 2 (ca. 200 kDa) again contained BclA, along with a 151 residue (10 cysteine) protein, which we named CsxB. This latter protein was also found in bands 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. These proteins in the high molecular weight bands are prime candidates to form structural components of the hairy nap and basal layer of the exosporium. Band 3 (ca. 60 kDa) also contained a carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, SpoIVA, and a LysM domain-containing protein. Band 4 (ca. 44 kDa) contained a number of potentially soluble proteins including for example a predicted aminotransferase, elongation factor Tu, glutamate dehydrogenase, and arginine deiminase, as well as CsxB. Band 5 (ca. 38 kDa), contained proteins annotated as aminotransferase, proline racemase, ornithine carbamoyltransferase, a pyruvate ferridoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase, and others, along with CsxB, a protein of the B. subtilis CotS family and a homologue of B. subtilis CotJC. Band 6 (ca. 30 kDa) identifications included CotJC, CotJB, a predicted 273 amino acid protein with 14 cys residues which we named CsxC and an NlpC/P60 cell wall peptidase family protein. In band 7 (ca. 19 kDa) CsxB, described above, was the sole identified component in this major band, which corresponds to the predicted size of the monomer.

To confirm the close similarity of C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792 to the sequenced strains, its csxA and csxB gene sequences were determined from PCR products of genomic DNA. The csxA gene and deduced protein sequence are both 100% identical to those of PA 3679, and those of csxB are 98% and 100% identical, respectively.

3.6. Protein profile of extracts from bulk C. sporogenes exosporium

C. sporogenes washed exosporium was incubated with detergent and the solubilized material was digested with trypsin. Sixty-eight proteins (Table 1 & SI-2), including CsxA, CsxB, CsxC and BclA, were identified. We also identified a second protein with a collagen-like domain; this has been named BclB as it has a C-terminal domain homologous (68% amino acid identity; Fig. S2) to that of BclB of B. anthracis.

3.7. Homologues in C. botulinum

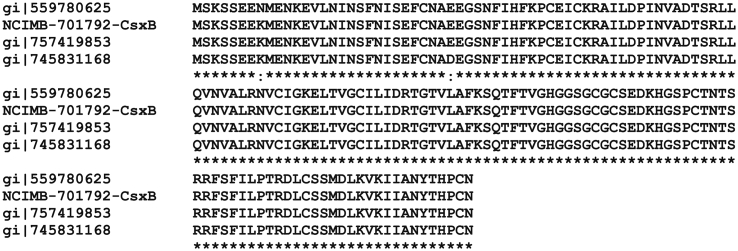

As so little is known of the exosporium in Clostridia, it is important to consider whether the major proteins identified in C. sporogenes are more widely distributed. The WGS database at NCBI was searched using BlastP. Homologues of the cysteine-rich proteins CsxA, CsxB and CsxC were found in C. botulinum Group I (Table 2). For example, CsxA is 100% conserved in C. botulinum strain Prevot 594 (Smith et al., 2015) and C. sporogenes PA 3679; homologues are present in other Group I strains, but are less conserved (78–87% identity; Table 2). C. botulinum strains in the C. sporogenes cluster share a near identical CsxB protein (99–100% identity), and a CsxB homologue (78% identity) is present in the other Group I cluster. The alignments of CsxA and CsxB with several C. botulinum homologues are shown in Fig. S3 and Fig. 5, respectively. CsxC is identical in C. botulinum strain Prevot 594, but is less closely conserved (61–77% identity) in other C. botulinum strains (Table 2). C. botulinum Eklund 17B was considered as a representative of the taxonomically distinct Group II (non-proteolytic) strains. It encodes a CsxA homologue (41% identity), but no homologues of CsxB and CsxC were detected. Homologues of CsxA and CsxB with lower amino acid identity (40%–30%) are present in a number of other Clostridium species, including Clostridium tetani, Clostridium beijerinkii, Clostridium pasteurianum, Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum, Clostridium senegalense, Clostridium kluyveri, Clostridium akagii and Clostridium tyrobutyricum, but no CsxC homologues were detected in other Clostridium species. Of these species listed, a true exosporium has only been demonstrated in C. pasteurianum (Mackey and Morris, 1972) and C. tyrobutyricum (T K Janganan, unpublished data).

Table 2.

Homologues of C. sporogenes exosporium proteins in C. botulinum Group I and other Clostridium species.

| Strain | CsxA |

CsxB |

CsxC |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Amino acid identity | |||

| C. botulinum_Prevot 594 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| C. botulinum B2 450 | 87 | 100 | 77 |

| C. botulinum Str. B Osaka05 | 86 | 99 | 77 |

| C. botulinum A3 Loch Maree | 77 | 78 | 65 |

| C. botulinum F Str. Langeland | 84 | 78 | 64 |

| C. botulinum Hall | 83 | 78 | 61 |

| C. tetani | ND | 43 | ND |

| C. beijerincki | 38 | 31 | ND |

aFrom WGS Blast (NCBI).

ND- No homologue detected.

Fig. 5.

Alignment of C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792 CsxB with C. botulinum homologues. CsxB from C. sporogenes NCIMB 701792 is compared to: gi|559780625, C. botulinum B str. Osaka05; gi|757419853, C. botulinum B2 450 and gi|745831168, C. botulinum Prevot 594.

The BclA protein, identified in LC-MS/MS by its N-terminal peptide, is less widely distributed. The gene is present in C. sporogenes and in C. botulinum Prevot 594, but not in other Group I members; the next closest homologue (46% identity) is currently detected in Clostridium scatologenes. The BclB protein is detected in C. sporogenes, C. botulinum Prevot 594 (82% identity) and in C. botulinum strain 277-00 (Type B2), but is absent in other Type I strains. Other proteins with CLR domains are commonly present in the Group I genomes examined, including one with a C-terminal domain distantly related (28% identity) to the large N-terminal domain of BclA of C. sporogenes.

3.8. Comparative architecture of the exosporium

Our analysis of the spore surface of C. sporogenes confirms the presence of a hairy nap and a paracrystalline basal layer, as well as additional surface appendages, and identifies a number of proteins in purified exosporium. It revealed interesting surface features of C. sporogenes spores, especially a “beaded fibril” type (Fig. 3) that has not been reported before. Hairy nap and appendages are common surface features of the exosporium of Clostridium spores (Hodgkiss et al., 1967, Hoeniger and Headley, 1969), and hair like projections have been reported on the surface of C. sporogenes ATCC 3584 exosporium (Panessa-Warren et al., 1997). Multiple tubular appendages have been observed in some strains of type E C. botulinum (Hodgkiss et al., 1966). Exosporium with single appendages has been observed in C. sporogenes OS strain 24 AS (Hodgkiss et al., 1966). Brunt et al. (2015) have elegantly shown by scanning EM how the germinated cell emerges from an aperture at one pole of the exosporium of C. sporogenes. Some features of C. sporogenes exosporium resemble those of the B. cereus group, where the exosporium also appears as a deformable sac-like layer, extended at one spore pole and more tightly associated at the other end (Ball et al., 2008); again, there is a hairy nap, and a crystalline basal layer (Kailas et al., 2011).

3.9. Exosporium protein comparisons

Whilst the architecture of the outer surface of the C. sporogenes spore resembles that of the B. cereus group, the protein composition is notably different. Proteins from purified exosporium from B. cereus and B. anthracis include high molecular weight complexes on SDS-PAGE, composed of three primary constituents of the exosporium structure, BclA, ExsF/BxpB and ExsY. By analogy, the presence of BclA, CsxA and CsxB proteins in high molecular weight material in C. sporogenes exosporium extracts suggests that they may play a similar role in the C. sporogenes structure. In addition to BclA, a second CLR protein BclB has been detected in total exosporium. Similarly organised CLR proteins have been identified as components of the hairy nap in exosporium of B. anthracis (Sylvestre et al., 2003, Thompson et al., 2012). The N-termini of B. anthracis BclA and BclB both contain a motif responsible for their localisation to the exosporium (Thompson and Stewart, 2008, Thompson et al., 2012), but this motif is not present in the BclA or BclB proteins of C. sporogenes. BxpB/ExsFA has been shown to be a component of the exosporium in B. anthracis and acts as an anchor protein for BclA into the exosporium, but no identifiable homologue of the ExsF protein is encoded in the sequenced genome of any Clostridial species, including C. sporogenes. We do not know whether BclA and BclB are functionally equivalent to those in B. anthracis, but if indeed they are nap components, it is likely that they are linked to the basal layer by a different mechanism from that in B. anthracis.

We found a number of soluble and cytosolic proteins by LC-MS/MS, as also described in B. cereus, B. anthracis (Todd et al., 2003, Liu et al., 2004). Some of these proteins are detectable even after washing the exosporium extensively with salt and SDS (Table 1 & SI-1-3). This suggests that proteins might be associated with, or trapped in, the exosporium layer; some may be residual contaminating vegetative cell or spore coat proteins. The collection of proteins identified in exosporium may also include appendage proteins, as these are present in our exosporium preparation, although they would represent only a small proportion of the total protein.

4. Conclusion

This work provides the first insight into the likely composition and organization of the exosporium of Group I C. botulinum strains; our study has identified exosporium proteins with homologues across a wider range of Clostridial species, and provides the first level of information for more detailed study of the exosporium of these important bacteria. CsxA, CsxB and CsxC are potential candidates for structural proteins of the exosporium of C. sporogenes and C. botulinum and their contribution will be explored further. A fundamental understanding of exosporium structure and properties in C. sporogenes and C. botulinum will inform future studies of biological function and inactivation regimes.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Adrian Brown, School of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, University of Durham for performing LC-MS/MS. JKH and NM gratefully acknowledge the Imagine: Imaging Life initiative at the University of Sheffield and the EPSRC for financial support through its Programme Grant scheme (Grant No. EP/I012060/1). PAB and TKJ gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Wellcome Trust (WT091322MA).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2016.06.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Ball D.A., Taylor R., Todd S.J., Redmond C., Couture-Tosi E., Sylvestre P., Moir A., Bullough P.A. Structure of the exosporium and sublayers of spores of the Bacillus cereus family revealed by electron crystallography. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:947–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydston J.A., Yue L., Kearney J.F., Turnbough C.L., Jr. The ExsY protein is required for complete formation of the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:7440–7448. doi: 10.1128/JB.00639-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury M., Greenfield P., Midgley D., Li D., Tran-Dinh N., Vriesekoop F., Brown J.L. Draft genome sequence of Clostridium sporogenes PA 3679, the common nontoxigenic surrogate for proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1631–1632. doi: 10.1128/JB.06765-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt J., Cross K.L., Peck M.W. Apertures in the Clostridium sporogenes spore coat and exosporium align to facilitate emergence of the vegetative cell. Food Microbiol. 2015;51:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A.T., Peck M.W. Genomes, neurotoxins and biology of Clostridium botulinum group I and group II. Res. Microbiol. 2015;166:303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkiss W., Ordal Z.J. Morphology of the spore of some strains of Clostridium botulinum type E. J. Bacteriol. 1966;91:2031–2036. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.5.2031-2036.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkiss W., Ordal Z.J., Cann D.C. The comparative morphology of the spores of Clostridium botulinum type E and the spores of the “OS mutant”. Can. J. Microbiol. 1966;12:1283–1284. doi: 10.1139/m66-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkiss W., Ordal Z.J., Cann D.C. The morphology and ultrastructure of the spore and exosporium of some Clostridium species. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1967;47:213–225. doi: 10.1099/00221287-47-2-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeniger J.F., Headley C.L. Ultrastructural aspects of spore germination and outgrowth in Clostridium sporogenes. Can. J. Microbiol. 1969;15:1061–1065. doi: 10.1139/m69-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.J., Todd S.J., Ball D.A., Shepherd A.M., Sylvestre P., Moir A. ExsY and CotY are required for the correct assembly of the exosporium and spore coat of Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:7905–7913. doi: 10.1128/JB.00997-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kailas L., Terry C., Abbott N., Taylor R., Mullin N., Tzokov S.B., Todd S.J., Wallace B.A., Hobbs J.K., Moir A., Bullough P.A. Surface architecture of endospores of the Bacillus cereus/anthracis/thuringiensis family at the subnanometer scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:16014–16019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109419108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequette Y., Garenaux E., Combrouse T., Dias Tdel L., Ronse A., Slomianny C., Trivelli X., Guerardel Y., Faille C. Domains of BclA, the major surface glycoprotein of the B. cereus exosporium: glycosylation patterns and role in spore surface properties. Biofouling. 2011;27:751–761. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2011.599842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Bergman N.H., Thomason B., Shallom S., Hazen A., Crossno J., Rasko D.A., Ravel J., Read T.D., Peterson S.N., Yates J., 3rd, Hanna P.C. Formation and composition of the Bacillus anthracis endospore. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:164–178. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.164-178.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey B.M., Morris J.G. The exosporium of Clostridium pasteurianum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1972;73:325–338. doi: 10.1099/00221287-73-2-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K., Kawata T., Takumi K., Kinouchi T. Ultrastructure of a hexagonal array in exosporium of a highly sporogenic mutant of Clostridium botulinum type A revealed by electron microscopy using optical diffraction and filtration. Microbiol. Immunol. 1980;24:507–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1980.tb02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panessa-Warren B.J., Tortora G.T., Warren J.B. Exosporial membrane plasticity of Clostridium sporogenes and Clostridium difficile. Tissue Cell. 1997;29:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(97)80031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Sabja D., Shen A., Sorg J.A. Clostridium difficile spore biology: sporulation, germination, and spore structural proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck M.W., Stringer S.C., Carter A.T. Clostridium botulinum in the post-genomic era. Food Microbiol. 2011;28:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Permpoonpattana P., Hong H.A., Phetcharaburanin J., Huang J.M., Cook J., Fairweather N.F., Cutting S.M. Immunization with Bacillus spores expressing toxin A peptide repeats protects against infection with Clostridium difficile strains producing toxins A and B. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:2295–2302. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00130-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S., Barcons V., Christenson H.K., Font J., Thomson N.H. The intrinsic resolution limit in the atomic force microscope: implications for heights of nano-scale features. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.J., Markowitz S.M., Macrina F.L. Transferable tetracycline resistance in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1981;19:997–1003. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.J., Hill K.K., Xie G., Foley B.T., Williamson C.H., Foster J.T., Johnson S.L., Chertkov O., Teshima H., Gibbons H.S., Johnsky L.A., Karavis M.A., Smith L.A. Genomic sequences of six botulinum neurotoxin-producing strains representing three clostridial species illustrate the mobility and diversity of botulinum neurotoxin genes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;30:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart G.C. The exosporium layer of bacterial spores: a connection to the environment and the infected host. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015;79:437–457. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00050-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre P., Couture-Tosi E., Mock M. Polymorphism in the collagen-like region of the Bacillus anthracis BclA protein leads to variation in exosporium filament length. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1555–1563. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1555-1563.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takumi K., Kinouchi T., Kawata T. Isolation and partial characterization of exosporium from spores of a highly sporogenic mutant of Clostridium botulinum type A. Microbiol. Immunol. 1979;23:443–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1979.tb00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium Z. Ongoing and future developments at the universal protein resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:214–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B.M., Stewart G.C. Targeting of the BclA and BclB proteins to the Bacillus anthracis spore surface. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70:421–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B.M., Hoelscher B.C., Driks A., Stewart G.C. Assembly of the BclB glycoprotein into the exosporium and evidence for its role in the formation of the exosporium ‘cap’ structure in Bacillus anthracis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;86:1073–1084. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd S.J., Moir A.J., Johnson M.J., Moir A. Genes of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus anthracis encoding proteins of the exosporium. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:3373–3378. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3373-3378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigand M.R., Pena-Gonzalez A., Shirey T.B., Broeker R.G., Ishaq M.K., Konstantinidis K.T., Raphael B.H. Implications of genome-based discrimination between Clostridium botulinum group I and Clostridium sporogenes strains for bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:5420–5429. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01159-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Q., Gu C., Rivera J., Hook M., Chen X., Pozzi A., Xu Y. Entry of Bacillus anthracis spores into epithelial cells is mediated by the spore surface protein BclA, integrin alpha2beta1 and complement component C1q. Cell. Microbiol. 2011;13:620–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.