Abstract

Humans are distinguished from the other living apes in having larger brains and an unusual life history that combines high reproductive output with slow childhood growth and exceptional longevity1. This suite of derived traits suggests major changes in energy expenditure and allocation in the human lineage, but direct measures of human and ape metabolism are needed to compare evolved energy strategies among hominoids. Here we used doubly labelled water measurements of total energy expenditure (TEE; kcal day−1) in humans, chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans to test the hypothesis that the human lineage has experienced an acceleration in metabolic rate, providing energy for larger brains and faster reproduction without sacrificing maintenance and longevity. In multivariate regressions including body size and physical activity, human TEE exceeded that of chimpanzees and bonobos, gorillas and orangutans by approximately 400, 635 and 820 kcal day−1, respectively, readily accommodating the cost of humans' greater brain size and reproductive output. Much of the increase in TEE is attributable to humans' greater basal metabolic rate (kcal day−1), indicating increased organ metabolic activity. Humans also had the greatest body fat percentage. An increased metabolic rate, along with changes in energy allocation, was crucial in the evolution of human brain size and life history.

Variation in life history reflects evolved differences in energy expenditure. Each organism must allocate its available metabolic energy, which is largely a function of body size, to the competing needs of growth, reproduction and maintenance, resulting in fundamental trade-offs among these vital tasks2–5. For example, species that reproduce faster than expected for their body mass generally have shorter maximum lifespans, as energy is directed towards reproductive output and away from maintenance2–5. Among primates, this trade-off framework has been expanded to consider the energy needed to grow and maintain large brains6,7.

In this light, humans present an energetic paradox. Humans in natural fertility populations reproduce more often, and produce larger neonates, than any other living hominoid, yet humans also have the longest lifespans and the largest, most metabolically costly brains1 (Extended Data Fig. 1). This uniquely human suite of derived, metabolically costly traits suggests a lifting of energetic constraints in the hominin line-age, but the critical underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. Some have hypothesized that a reduced gut8 or increased locomotor efficiency9 provided the extra energy needed for brain expansion. However, phylogenetically informed analyses suggest that gut reduction is insufficient to explain increased human brain size1, and, although human walking is more economical10, traditional hunter–gatherers travel so much farther per day11 that their daily ranging costs are no lower than wild chimpanzees' (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, provisioning of young offspring and their mothers helps to shorten human inter-birth intervals and increase the pace of reproduction1, but reproduction remains relatively costly for human mothers (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, it is unclear whether food sharing or other dietary changes are sufficient to fuel larger brains, larger neonates and longer lifespans without an acceleration in metabolic rate to harness increased energy acquisition.

Here, we test the hypothesis that humans have evolved an accelerated metabolic rate and larger energy budget, accommodating larger brains, greater reproductive output and longer lifespans without the expected energetic trade-offs. Increased TEE (kcal day−1) has previously been discounted as an explanation for the human energetic paradox1,8, in part because human basal metabolic rate (BMR; kcal day−1) is broadly similar to that of other primates8,11. However, variation in TEE and BMR among humans and the great apes, our closest evolutionary relatives, is largely unstudied. Lacking sufficient data on TEE and BMR in apes, previous analyses have been unable to compare metabolic rates across the entire hominoid clade and test for metabolic acceleration in humans.

We used the doubly labelled water method12 to measure TEE in mixed-sex samples of adult chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes; n = 27), bonobos (Pan paniscus; n = 8), Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla; n = 10) and orangutans (Pongo spp.; n = 11), and compared these data to similar measures of TEE in a large, adult human sample13 (Homo sapiens; n = 141); this method also provides a measure of body composition (Methods and Table 1). TEE was measured over 7–10 days while individuals followed their normal daily routine. We also compared published measurements of BMR in humans, chimpanzees and orangutans, and we estimated daily locomotor energy expenditure and BMR for adults in our TEE sample to assess their contribution to variation in TEE. Comparisons were performed at the genus level, both to avoid the issue of close phylogenetic relatedness for chimpanzees and bonobos, and because no metabolic differences were apparent between these two species.

Table 1. Age, body size and composition, and TEE.

| Genus | Sex | n | Age (years) (s.d.) | Mass (kg) (s.d.) | FFM (kg) (s.d.) | Body fat* (%) (s.d.) | TEE† (kcal day 1) (s.d.) | BMR‡ | Walk and climb‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo | Female | 76 | 33.5 (6.0) | 80.1 (19.8) | 46.1 (7.4) | 41.1 (7.1) | 2,190 (381) | 1,474 | 183 |

| Male | 65 | 32.6 (5.4) | 73.8 (15.2) | 56.1 (7.9) | 22.9 (7.6) | 2,721 (569) | 1,640 | 226 | |

| Pan | Female | 17 | 25.8 (11.3) | 46.4 (8.1) | 43.3 (7.8) | 9.0 (5.5) | 1,722 (363) | 1,214 | 102 |

| Male | 18 | 22.3 (10.7) | 57.9 (13.4) | 53.8 (11.7) | 8.4 (4.9) | 2,145 (546) | 1,401 | 120 | |

| Gorilla | Female | 6 | 19.7 (4.1) | 73.7 (7.3) | 63.3 (7.0) | 13.9 (6.4) | 2,030 (527) | - | 110 |

| Male | 4 | 24.5 (11.7) | 166.4 (42.5) | 148.3 (27.0) | 15.2 (4.6) | 3,630 (839) | - | 253 | |

| Pongo | Female | 5 | 27.6 (5.3) | 58.2 (4.0) | 44.3 (2.5) | 23.4 (8.8) | 1,476 (268) | 984 | 88 |

| Male | 6 | 20.0 (10.8) | 76.7 (34.1) | 62.4 (23.3) | 16.4 (8.6) | 1,617 (289) | 1,090 | 163 |

s.d., standard deviation.

Excludes n = 6 Pan subjects with negative calculated body fats (Methods).

Calculated for Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo using equation 7.17 in ref. 12.

Estimated BMR and locomotion costs were calculated from body mass and daily activity (Methods).

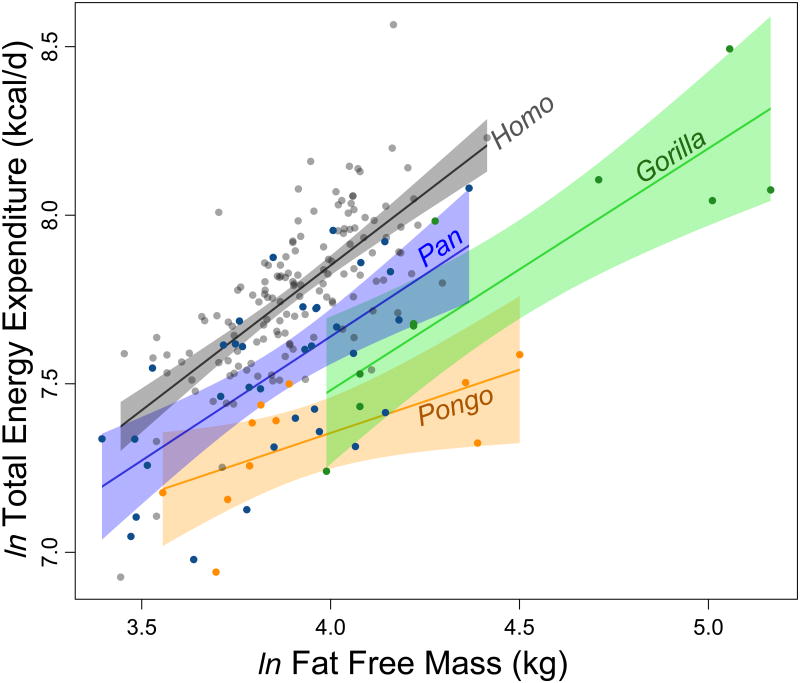

Humans exhibited greater TEE than other hominoids, with larger daily energy budgets than all apes except adult male gorillas (Table 1). Fat-free mass (FFM) explained 34% of the variance in TEE (t(195) = 10.18, r2 = 0.34, P < 0.001; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). Differences among genera accounted for an additional 27% of the variance in TEE, with humans having the highest TEE, followed in order by Pan, Gorilla and Pongo (P ≤ 0.001 for all comparisons; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3). For comparison, mean FFM was similar for Homo, Pan and Pongo cohorts, yet mean human TEE was ∼27% greater than Pan and ∼58% greater than Pongo. Body fat was weakly, negatively correlated with TEE (β= −0.04 ± 0.02, P = 0.02); age (P = 0.70) and sex (P = 0.26) were not significant covariates in TEE models including FFM, fat mass and genus (Supplementary Table 3). Results were robust across different models for calculating TEE from isotope enrichment (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1. TTE and FFM for hominoids.

Humans (Homo, grey, n = 141), chimpanzees and bonobos (Pan, blue, n = 35), gorillas (Gorilla, green, n = 10), and orangutans (Pongo, orange, n = 11). Lines and shaded regions indicate least squares regressions and 95% confidence intervals for each genus. TEE for Homo exceeds other genera in a general linear model accounting for FFM, fat mass and other variables (P 0.001; Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Together, BMR and daily locomotor expenditure accounted for much of the variation in TEE among genera. The mean estimated daily energy cost of walking and climbing among apes in our sample was similar across genera and ∼100 kcal day−1 below estimated daily walking cost in our human sample (Table 1). Our analyses of published measurements14–16 indicate that BMR is lower in Pan than in comparably aged humans, in analyses controlling for sex, age and body mass (P < 0.001; Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2). The few measurements of Pongo BMR16,17 appear to be lower still (Extended Data Fig. 2); no data for the Gorilla BMR are available. For cohorts in the TEE data set, estimated BMR for Homo was ∼200 kcal day−1 greater than Pan and ∼500 kcal day−1 greater than Pongo (Table 1). Estimated physical activity levels (PALs: TEE/estimated BMR; see Table 1), were similar across genera (Homo: female 1.5, male 1.7; Pan: female 1.4, male 1.5; Pongo: female 1.5, male 1.5), indicating that organ activity contributed more than physical activity to variations in TEE.

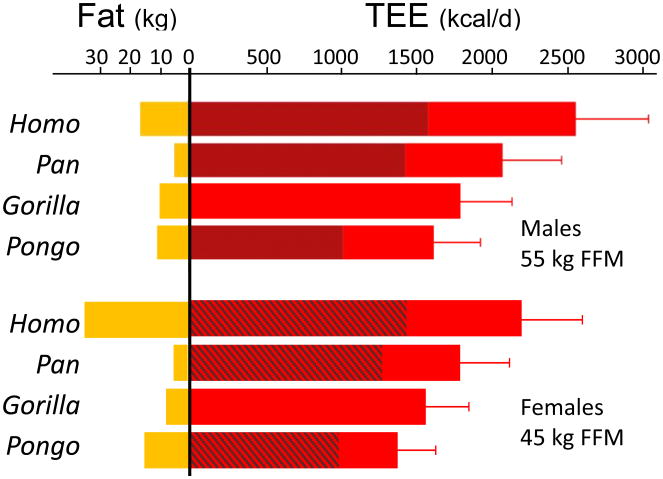

Figure 2. Predicted TEE, BMR and fat mass for adult hominoids.

Values are estimated for males (55 kg FFM) and females (45 kg FFM), using the same FFM across genera. TEE (red bars) is estimated from FFM, fat mass and genus using model C in Supplementary Table 3; error bars represent model standard error. BMR (darker red regions) is estimated from body mass (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2); no BMR data are available for Gorilla. Fat mass (yellow bars) is calculated from FFM using body fat percentages in Table 1.

Body fat percentage, measured from isotope dilution12, was markedly higher in humans than other hominoids in our TEE sample, and only humans exhibited a significant sex difference (Table 1). Body fat percentage was remarkably low for Pan, consistent with measures from dissection18, and somewhat higher for Gorilla and Pongo. Indeed, body fat percentages for captive apes were comparable to, or even below, average body fat percentages for humans in physically active, traditional hunter–gatherer populations19.

Together, these results indicate substantial metabolic evolution across the hominoid clade and a previously uncharacterized diversity in TEE, BMR and body fat percentage (Fig. 2). For a given FFM, humans have greater TEE, BMR and fat mass than other hominoids. Chimpanzees and bonobos have the next largest energy budgets but carry the least amount of body fat. Gorillas have lower TEE and greater body fat than Pan. Orangutans have exceptionally low TEE and BMR, and fat percentages similar to gorillas (Table 1).

Comparisons of BMR and TEE indicate that hominin brain and life history evolution were fuelled in large part by increased mass-specific organ metabolic rates (kcal g−1 h−1), and not solely through anatomical or physiological trade-offs. BMR reflects the summed metabolic activity of the organs at rest and is largely shaped by organs with high mass-specific metabolic rates such as the brain, liver and gastrointestinal tract20. If, as assumed in previous studies, organ-mass-specific metabolic rates were similar across hominoids, then humans and apes with the same FFM should have similar BMRs — the cost of humans' larger brain offset by a reduced gastrointestinal tract8. Instead, BMR and TEE are substantially greater for humans, controlling for FFM (Table 1, Figs 1, 2 and Extended Data Fig. 2), indicating an evolutionary increase in the metabolic activity of at least some organ systems. Humans' greater BMR and TEE could readily accommodate the marginal cost of increased reproductive output, estimated at ∼ 130 kcal day−1 over the course of a woman's reproductive career in natural fertility populations (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Greater metabolic activity could also support humans' derived brain metabolism21 and increased somatic maintenance and longevity1, but more comparative analyses are needed to identify specific mechanisms and associated metabolic costs.

Analysing relatively sedentary human and ape populations allowed us to compare cohorts with similar FFMs, PALs and locomotor expenditures (Table 1), but the pattern of TEE, BMR and body composition variation among genera is expected to hold across more physically active populations. When controlling for body size, TEE is remarkably consistent across populations within a species, regardless of activity level22: traditional hunter–gatherers have similar size-corrected TEEs to people living in cities19, and zoo-housed populations of primates and other mammals are similar to their counterparts in the wild22–24. Humans in traditional foraging and farming populations and apes in the wild will generally have lower body fat percentages19 than the cohorts in the TEE sample (Table 1), but again the pattern of differences seen here is expected to persist: even in captivity, body fat percentage in Pan is remarkably low and fat percentages for Pongo and Gorilla fall near the very lowest ranges for healthy, physically active human populations19.

Expansion of the hominin energy budget challenges current models of life history and brain evolution predicated on metabolic stasis and constraint1,2,5–9. Evolved increases in BMR and TEE do not diminish the importance of gut reduction, efficient walking, dietary change and maternal provisioning in the hominin lineage, but rather place these critical adaptations within a different energetic framework. Increased TEE exposes individuals to a greater likelihood of energy shortfalls, providing strong selection for behavioural and anatomical adaptations to mitigate this risk. Gut reduction8 allows for greater energy allocation to reproduction and maintenance (including larger brains) while limiting the increase in BMR and TEE. Improved walking efficiency10, a dietary shift to more energy-dense foods (for example, meat, tubers), and the adoption of cooking25 all effectively increase the net energy gained from foraging, and may have had an essential role in the evolutionary expansion of the hominin energy budget. Food sharing1 provides an additional source of food energy, and along with increased body fat9, provides an important buffer against energy short-falls, particularly for children and for females shouldering the added energetic burdens of reproduction. We hypothesize that food sharing and increased body fat coevolved with greater TEE to mitigate the inherent risk of increased energy demands.

Metabolic measurements of living hominoids resolve the human energetic paradox and may also point towards strategies for combating obesity and metabolic disease. Humans exhibit an evolved predisposition to deposit fat whereas other hominoids remain relatively lean, even in captivity where activity levels are modest. Untangling the evolutionary pressures and physiological mechanisms shaping the diversity of metabolic strategies among living hominoids may aid efforts to promote and repair metabolic health for humans in industrialized populations and apes in captivity.

Online Content

Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Methods

Sample

Adult apes (age ≥ 10 years) were housed in Association of Zoos and Aquariums accredited zoos in the United States, or in sanctuaries in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with large enclosures. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Institutional approvals were obtained from Hunter College and participating facilities before data collection. Human data were drawn from a recent large global study13 (United States, Ghana, South Africa, Seychelles, Jamaica; institutional approvals from local governments and Loyola University, and each subject's informed consent, were obtained before data collection). Men and women employed in manual labour were excluded from analyses to better match activity levels across species. Apes were excluded from analyses if they had a dilution space ratio less than 1.00, or had a calculated body fat percentage below −10%, either of which could signal an error in dosing or sample processing. Owing to normal measurement error, the isotope dilution method for calculating body composition can produce marginally negative body fat estimates in subjects with fat percentages near 0. This occurred in n = 6 Pan subjects (range: −1 to −6% body fat), which is unsurprising given the low body fat percentage in Pan18 (Table 1). These subjects were included in analyses unless otherwise noted; they were excluded from analyses including fat mass (Supplementary Table 3), because negative values cannot be log-transformed. Pregnant and lactating mothers (n = 2 bonobo and 2 gorillas) were retained in the sample because ‘pregnant/lactating’ did not emerge as a significant factor for TEE in multiple regression with FFM and genus (t(191) = −0.48, P = 0.68). The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Dosing and sampling

Dosing, sampling and analytical protocols for humans were as described previously13. Ape protocols were as described previously23, and apes from that study (n = 14 Pan, n = 3 Pongo, n = 5 Gorilla) are included in this analysis. Apes drank a sufficient dose of DLW (6% 2H2O, 10% H218O; Sigma-Aldrich) to achieve targeted enrichment for their body mass12, which was measured using a digital scale before the study. Urine or saliva samples were collected once before dosing and then 3–5 times post-dose, over the course of 7–10 days. Isotopic enrichment (2H and 18O) was measured using isotope ratio mass spectrometry or cavity ring down mass spectrometry. Analysis of residuals indicates results were similar across laboratories and methods (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Calculating TEE

Isotope depletion rates and dilution spaces were calculated via the slope-intercept method12. Three to five post-dose urine samples were analysed for each subject, enabling us to identify and remove contaminated samples from analysis. Isotope depletion rates were used to calculate ape TEE (kcal day−1) using equation 7.17 in ref. 12, using a food quotient of 0.95 (ref. 23) and a dilution space ratio of 1.04 following observed ratios in all ape species (1.04 ± 0.02, n = 56 subjects; no effect of genus: F(53) = 0.55, P = 0.58 ANOVA). We also calculated TEE using equation 17.15 in ref. 12, which is tailored to human subjects and assumes human-like fractionation and insensible water loss. Ape TEE values using the human-tailored equation are 11 ± 3% greater, but the pattern of TEE differences among hominoids is robust to the choice of equation (Supplementary Table 3). We prefer the more generalized mammalian equation for apes, since apes differ from humans in sweating capability and nasal morphology and are therefore likely to be more like other mammals (rather than humans) in fractionation and insensible water loss.

TEE analysis

Variation in TEE was examined via multiple regression26 using ln-transformed values for TEE, FFM and fat mass to reduce heteroscedasticity of residuals. Comparisons were made at the genus level due to the close phylogenetic relatedness of bonobos and chimpanzees. Bonobos and chimpanzees did not differ (F(32) = 0.007, P = 0.80 ANCOVA) in TEE in analyses controlling for FFM.

Locomotor costs

Humans were fitted with triaxial accelerometers (Actical, Phillips Respironics) and counts per minute were logged for 7 days, corresponding with the DLW measurement period15. Accelerometry was not feasible for apes. Instead, physical activity was recorded using direct observation for a minimum of 20 h over the DLW measurement period. Distances walked and climbed were recorded every 15 min, using measurements of the enclosures to calibrate distance estimates. Rates of walking and climbing (metres h−1) were calculated and multiplied by 12 to give the estimated distance walked and climbed during the daytime. Night-time activity was not observable in apes and was therefore excluded from analyses for all species.

BMR

Published respirometry measurements of BMR for chimpanzees15,16 (age: 2 months to 15 years) and comparably aged humans14 (3–18 years) were ln-transformed and analysed using multiple regression26 controlling for sex, age, and ln-transformed body mass. Humans had higher BMRs than chimpanzees (P < 0.001) in all analyses (Supplementary Table 3). These data, along with the few available data for orangutan BMR16,17, are plotted in Extended Data Fig. 2. Allometric regressions for chimpanzees and orangutans (Extended Data Fig. 2) were used to estimate BMR for the Pan and Pongo cohorts (Table 1). Published BMR prediction equations for adult humans27 were used for the Homo cohort in Table 1.

Extended Data

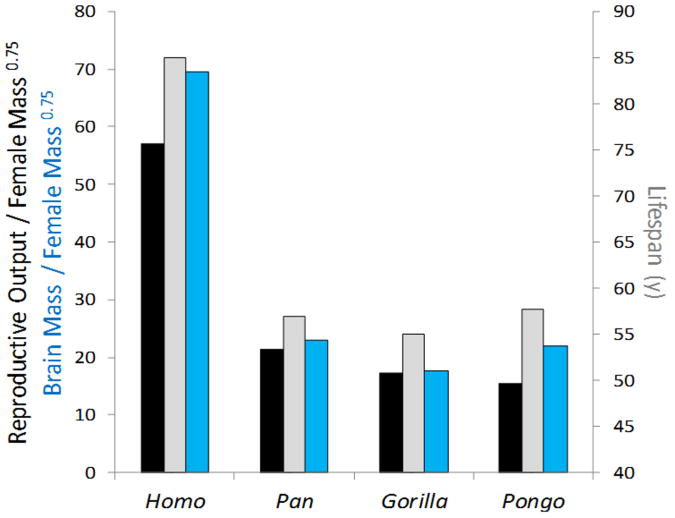

Extended Data Figure 1. The human energetic paradox.

Humans achieve greater reproductive output (g year−1; black bar) and have larger brains (g; blue bar) relative to female metabolic mass (kg0.75) than any of the great apes, yet also achieve longer lifespans (grey bar). Human data are from traditional hunter–gatherer and subsistence farming populations; ape data are from populations in the wild1 (see Supplementary Table 2).

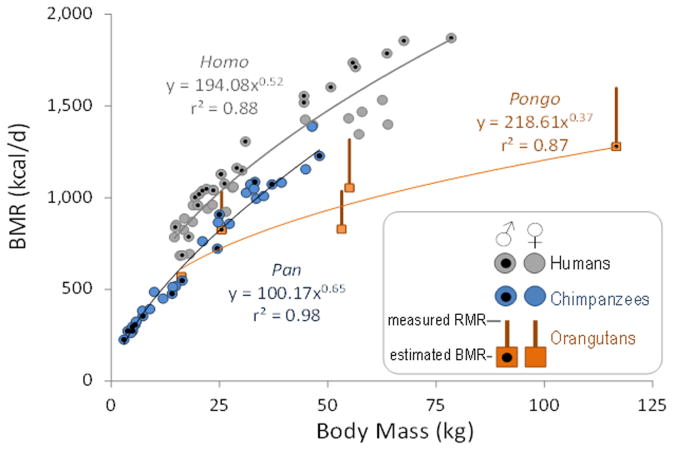

Extended Data Figure 2. BMRs for humans, chimpanzees and orangutans.

Available BMR data for chimpanzees15,16 are primarily from juveniles (age: 2 months to 15 years), and are shown here against comparably aged humans14 (3–18 years). Humans have greater BMRs than chimpanzees in a general linear model of ln-transformed BMR and mass controlling for age and sex (P < 0.001; Supplementary Table 3). Note that in humans (but not chimpanzees), males have greater BMRs for a given body mass, reflecting their greater proportion of FFM (that is, lower body fat percentage). The available data for orangutan BMR consists of one juvenile individual16 (no age reported, mass 16.2 kg). Resting metabolic rates (RMRs; kcal day−1), measured in alert orangutans while sitting17, are also shown. The top of the bar indicates the measured RMR for those individuals, and the bottom square indicates estimated BMR bas ed on those measurements17, assuming BMR = 0.8RMR. No BMR data are available for gorillas. Symbols marked with black circles are males. Allometric regressions shown for Pan (y = 100.17x0.65) and Pongo (y = 218.61x0.37) and were used to estimate BMR for the adult cohorts in Table 1. Human BMR in Table 1 was estimated from published, sex-specific predictive equations for adults27.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank participating zoos and staff for their efforts: Houston Zoo, Indianapolis Zoo, Jacksonville Zoo, Lincoln Park Zoo, Milwaukee County Zoo, North Carolina Zoo, Oklahoma City Zoo, Oregon Zoo, Zoo Atlanta, Woodland Park Zoo, Dallas Zoo, Brookfield Zoo and Columbus Zoo. We thank B. Moumbaka for assistance administering doses and collecting samples for analysis. We thank R. Atencia and C. Andre for supporting this project. Work at Tchimpounga and Lola Ya Bonobo was performed under the authority of the Ministry of Research and the Ministry of Environment in the Democratic Republic of Congo (research permit #MIN.RS/SG/004/2009) and the Ministry of Scientific Research and Technical Innovation in the Congo Republic (research permit 09/MRS/DGRST/DMAST), with samples imported under CITES permits 09US223466/9 and 9US207589/9. L. Christopher, K. Stafford and J. Paltan assisted with sample analyses. Funding was provided by the US National Science Foundation (BCS-1317170), National Institutes of Health (R01DK080763), L.S.B. Leakey Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation (Gr. 8670), University of Arizona and Hunter College.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions H.P. and S.R.R. designed the study; H.P., M.H.B., D.A.R., H.D., B.H., K.W., A.L., L.R.D., J.P.-R., P.B., T.E.F., E.V.L., R.W.S. and S.R.R. collected data; H.P., R.D.-A., M.E.T. and D.S. analysed data. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Isler K, van Schaik CP. How our ancestors broke through the gray ceiling. Curr Anthropol. 2012;53:S453–S465. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charnov EL. Life History Invariants. Oxford Univ. Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Allen AP, Savage VM, West BG. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology. 2004;85:1771–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stearns SC. The Evolution of Life Histories. Oxford Univ. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charnov EL. The optimal balance between growth rate and survival in mammals. Evol Ecol Res. 2004;6:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charnov EL, Berrigan D. Why do primates have such long life spans and so few babies? Evol Anthropol. 1993;1:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isler K, van Schaik CP. The Expensive Brain: a framework for explaining evolutionary changes in brain size. J Hum Evol. 2009;57:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiello LC, Wheeler P. The expensive tissue hypothesis. Curr Anthropol. 1995;36:199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarrete A, van Schaik CP, Isler K. Energetics and the evolution of human brain size. Nature. 2011;480:91–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pontzer H, Raichlen DA, Rodman PS. Bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion in chimpanzees. J Hum Evol. 2014;66:64–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonard WR, Robertson ML. Comparative primate energetics and hominid evolution. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;102:265–281. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199702)102:2<265::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speakman JR. Doubly Labelled Water: Theory & Practice. Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontzer H, et al. Constrained total energy expenditure and metabolic adaptation to physical activity in adult humans. Curr Biol. 2016;26:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butte NF. Fat intake of children in relation to energy requirements. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(suppl):1246S–1252S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1246s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruhn JM, Benedict FG. The respiratory metabolism of the chimpanzee. Proc Am Acad Arts Sci. 1936;71:259–326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.6.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruhn JM. The respiratory metabolism of infrahuman primates. Am J Physiol. 1934;110:477–484. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pontzer H, Raichlen DA, Shumaker RW, Ocobock C, Wich SA. Metabolic adaptation for low energy throughput in orangutans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14048–14052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zihlman AL, Bolter DR. Body composition in Pan paniscus compared with Homo sapiens has implications for changes during human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:7466–7471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505071112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pontzer H, et al. Hunter-gatherer energetics and human obesity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Bosy-Westphal A, Schautz B, Müller M. Mechanistic model of mass-specifc basal metabolic rate: evaluation in healthy young adults. Int J Body Compos Res. 2011;9:147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauernfeind AL, et al. Evolutionary divergence of gene and protein expression in the brains of humans and chimpanzees. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:2276–2288. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontzer H. Constrained total energy expenditure and the evolutionary biology of energy balance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2015;43:110–116. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pontzer H, et al. Primate energy expenditure and life history. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1433–1437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316940111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nie Y, et al. Exceptionally low daily energy expenditure in the bamboo-eating giant panda. Science. 2015;349:171–174. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carmody RN, Weintraub GS, Wrangham RW. Energetic consequences of thermal and nonthermal food processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19199–19203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112128108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry CJ. Basal metabolic rate studies in humans: measurement and development of new equations. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:1133–1152. doi: 10.1079/phn2005801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.