Abstract

Severe sepsis is a major concern in the intensive care unit (ICU), although there is very little epidemiological information regarding severe sepsis in Japan. This study evaluated 3195 patients with severe sepsis in 42 ICUs throughout Japan. The patients with severe sepsis had a mean age of 70 ± 15 years and a mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score of 23 ± 9. The estimated survival rates at 28 and 90 days after ICU admission were 73.6 and 56.3 %, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40560-016-0169-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Severe sepsis, Mortality, Epidemiology, Acute respiratory failure, Acute kidney injury, Disseminated intravascular coagulation, Organ failure, Septic shock

Background

Many recent multicenter epidemiological studies have evaluated sepsis [1–7], although there is very little information regarding its epidemiology in Japan [1, 2]. Despite the limited amount of Japanese information, epidemiological data regarding severe sepsis are important for guiding clinical practice and the design of clinical studies. Therefore, the present study aimed to retrospectively evaluate a large population of patients with severe sepsis in intensive care units (ICUs) throughout Japan.

Methods

The present study analyzed the unlinkable anonymized database of the Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (JSEPTIC DIC) study [8]. Cases of shock, respiratory failure, or renal failure were defined as patients with a cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of ≥4 on day 1 [9]. Cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) were defined as patients with a Japanese Association for Acute Medicine DIC score of ≥4 on day 1. All data were expressed as number (percent), mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Survival rates were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

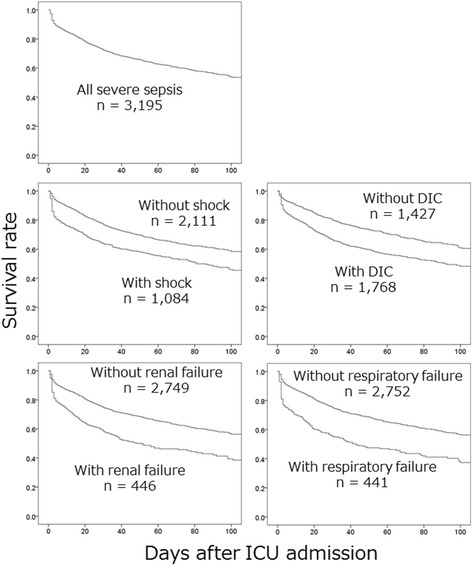

The present study included 3195 consecutive patients (2111 patients without shock and 1084 patients with shock). These patients included 1916 men (mean age 68 ± 14 years) and 1279 women (mean age 71 ± 15 years). The mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score among all patients was 23 ± 9. The primary infection sites are presented in Table 1. The blood culture results and responsible microorganisms are presented in Table 2. The frequencies of administering various adjunct treatments for severe sepsis during the first 7 days after ICU admission are shown in Table 3. The survival curves for patients with and without various medical conditions are presented in Fig. 1. The estimated survival rates at 28 and 90 days among all patients with severe sepsis after the ICU admission were 73.6 and 56.3 %, respectively.

Table 1.

Primary infection site responsible for the sepsis

| Without shock | With shock | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2111 | n = 1084 | n = 3195 | |

| Abdomen | 661 (31 %) | 371 (34 %) | 1032 (32 %) |

| Lung/thorax | 575 (27 %) | 252 (23 %) | 827 (26 %) |

| Urinary tract | 349 (17 %) | 160 (15 %) | 509 (16 %) |

| Bone/soft tissue | 251 (12 %) | 123 (11 %) | 374 (12 %) |

| Cardiovascular system | 54 (3 %) | 14 (1 %) | 68 (2 %) |

| Central nervous system | 44 (2 %) | 19 (2 %) | 63 (2 %) |

| Catheter-related | 23 (1 %) | 21 (2 %) | 44 (1 %) |

| Other | 37 (2 %) | 23 (2 %) | 60 (2 %) |

| Unknown | 117 (6 %) | 101 (9 %) | 218 (7 %) |

Data are expressed as number (percent)

Table 2.

Microorganisms responsible for the sepsis and blood culture results

| Without shock | With shock | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2111 | n = 1084 | n = 3195 | |

| Microorganisms responsible for the sepsis | |||

| Gram-negative rod | 774 (35%) | 421 (39%) | 1165 (37%) |

| Gram-positive coccus | 477 (23%) | 261 (24%) | 738 (23%) |

| Fungus | 43 (2%) | 14 (1%) | 57 (2%) |

| Virus | 20 (1%) | 8 (1%) | 28 (1%) |

| Mixed infection | 254 (12%) | 146 (14%) | 400 (13%) |

| Other | 40 (2%) | 18 (2%) | 58 (2%) |

| Unknown | 533 (25%) | 216 (20%) | 749 (23%) |

| Blood culture | |||

| Positive | 866 (41%) | 540 (50%) | 1406 (44%) |

| Negative | 1,083 (51%) | 508 (47%) | 1591 (50%) |

| Not taken | 162 (8%) | 36 (3%) | 198 (6%) |

Data are expressed as number (percent)

Table 3.

Frequencies of various adjunct treatments for severe sepsis during the first 7 days after the ICU admission

| Adjunct treatments | |

|---|---|

| DIC treatments | 1498 (47%) |

| Antithrombin | 990 (31%) |

| Thrombomodulin | 856 (27%) |

| Co-administration of antithrombin and thrombomodulin | 496 (16%) |

| Protease inhibitors | 392 (12%) |

| Heparinoids | 167 (5%) |

| Immunoglobulin | 976 (31%) |

| Low-dose steroids | 777 (24%) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 890 (28%) |

| Non-renal indication renal replacement therapy | 266 (8%) |

| Polymyxin B-direct hemoperfusion | 692 (22%) |

Data are presented as number (percentage)

DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation, ICU intensive care unit

Fig. 1.

Survival curves for patients with and without various medical conditions. The patients with medical conditions exhibited a poorer survival rate, compared to the patients without the conditions. Cases of shock, respiratory failure, or renal failure were defined as a cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of ≥4 on day 1. Cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) were defined as a DIC score of ≥4 on day 1

Discussion

The present study evaluated the characteristics, treatments, and outcomes from 3195 patients with severe sepsis in 42 ICUs throughout Japan. The earlier epidemiological reports from after 2005 are summarized in the Additional file 1: Table S1. Although two previous Japanese studies have reported epidemiological information from 890 Japanese patients with severe sepsis, most of the participating institutions were university hospitals [1, 2]. In contrast, approximately half of the participating institutions in the present study were municipal hospitals. Furthermore, we included both general and emergency ICUs. Nevertheless, the distributions of age, severity, and mortality rates in the present study were similar to the findings from two previous Japanese studies [1, 2].

Patients with severe sepsis in other countries are generally younger than their Japanese counterparts [1–7]. Furthermore, other countries have higher mortality rates for patients with severe sepsis, compared to the rate from the present study, although the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores are similar for Japanese patients and other patients with sepsis [1–7]. However, the reports from the other countries evaluated patients with sepsis during an earlier period (2002–2010), compared to the patients from the three Japanese reports (2007–2013) [1–7]. Furthermore, mortality among patients with sepsis has decreased on an annual basis, and these factors may explain the different mortality rates in Japan and other countries.

The present study’s mortality rates for severe sepsis with and without shock are similar to the results from previous Japanese studies [1, 2]. However, severe sepsis is frequently complicated by respiratory failure, renal failure, and DIC [10], and the previous studies did not evaluate the mortality rates for severe sepsis in cases with respiratory or renal failure [1, 2]. Thus, the present study provides the first survival curve data for Japanese patients with severe sepsis according to their complications with shock, respiratory failure, renal failure, or DIC.

Abbreviations

DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ICU, intensive care unit; JSEPTIC DIC, Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

There was no financial support for the present study.

Availability of data and material

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Individual Case Data Repository (UMIN000012543, http://www.umin.ac.jp/icdr/index-j.html). Please contact the corresponding author to access the data.

Authors’ contributions

HM, SS, US, YK, KD, IY, SM, TK, and MT designed the study and reviewed the data set. HM, KD, SS, IY, TK, AT, IF, YS, HK, NT, OT, NE, NY, SR, YY, SM, UK, OY, WM, TA, SN, KY, TH, KI, KY, MW, NS, MT, TH, TS, UK, TT, KH, AK, KT, IY, AH, MM, YM, SK, and HN collected and assessed the data at each institution. HM interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors also read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Hayakawa M received a grant for basic research and lecturer’s fees from Asahi Kasei Pharma Co. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The JSEPTIC DIC study reviewed information from consecutive patients who were admitted to 42 ICUs at 40 institutions throughout Japan for treatment of severe sepsis or septic shock between January 2011 and December 2013 [8]. The study’s design was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each hospital, and the requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design.

Additional file

Epidemiological information from previous reports after 2005. (DOC 48 kb)

References

- 1.Ogura H, Gando S, Saitoh D, Takeyama N, Kushimoto S, Fujishima S, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in Japanese intensive care units: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of infection and chemotherapy : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2014;20:157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuda N, Oda N, Aibiki M, Ikeda H, Imaizumi H, Endo S, et al. 2007 JSICM Sepsis 1st Registry: management of severe sepsis and septic shock in Japan. J Jpn Soc Intensive Care Med. 2013;20:329–34. doi: 10.3918/jsicm.20.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou J, Qian C, Zhao M, Yu X, Kang Y, Ma X, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in intensive care units in mainland China. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang CT, Tsai YJ, Tsai PR, Yu CJ, Ko WJ. Epidemiology and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in surgical intensive care units in Northern Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2136. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beale R, Reinhart K, Brunkhorst FM, Dobb G, Levy M, Martin G, et al. Promoting Global Research Excellence in Severe Sepsis (PROGRESS): lessons from an international sepsis registry. Infection. 2009;37:222–32. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8203-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng B, Xie G, Yao S, Wu X, Guo Q, Gu M, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in critically ill surgical patients in ten university hospitals in China. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2538–46. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000284492.30800.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlsson S, Varpula M, Ruokonen E, Pettila V, Parviainen I, Ala-Kokko TI, et al. Incidence, treatment, and outcome of severe sepsis in ICU-treated adults in Finland: the Finnsepsis study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:435–43. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayakawa M, Yamakawa K, Saito S, Uchino S, Kudo D, Iizuka Y, et al. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin and mortality in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. A multicentre retrospective study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:1157–66. doi: 10.1160/TH15-12-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent JL, de Mendonca A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on "sepsis-related problems" of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1793–800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. Jama. 1995;273:117–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520260039030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]