Abstract

Background:

Motivated and committed employees deliver better health care, which results in better outcomes and higher patient satisfaction. Objective: To assess the Organizational Commitment and Intrinsic Motivation of Primary Health Care Providers (HCPs) in New Delhi, India.

Materials and Methods:

Study was conducted in 2013 on a sample of 333 HCPs who were selected using multistage stage random sampling technique. The sample includes medical officers, auxiliary nurses and midwives, and pharmacists and laboratory technicians/assistants among regular and contractual staff. Data were collected using the pretested structured questionnaire for organization commitment (OC), job satisfiers, and intrinsic job motivation. Analysis was done by using SPSS version 18 and appropriate statistical tests were applied.

Results:

The mean score for OC for entire regular staff is 1.6 ± 0.39 and contractual staff is 1.3 ± 0.45 which has statistically significant difference (t = 5.57; P = 0.00). In both regular and contractual staff, none of them show high emotional attachment with the organization and does not feel part of the family in the organization. Contractual staff does not feel proud to work in a present organization for rest of their career. Intrinsic motivation is high in both regular and contractual groups but intergroup difference is significant (t = 2.38; P < 0.05). Contractual staff has more dissatisfier than regular, and the difference is significant (P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

Organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation of contractual staff are lesser than the permanent staff. Appropriate changes are required in the predictors of organizational commitment and factors responsible for satisfaction in the organization to keep the contractual human resource motivated and committed to the organization.

Keywords: Employees, motivation, organization commitment, Primary Urban Health Center, salary

Introduction

Good human resource management drives employee satisfaction and commitment in the organization. Satisfied and committed employees deliver better health care, which results in better outcomes and higher patient satisfaction.[1,2,3]

Organizational commitment is the psychological attachment of an employee to the organization.[4] There are three types of organizational commitment (i) affective, (ii) continuance, and (iii) normative commitment. Affective commitment relates to an employee's emotional attachment to the organization and its goals. Continuance commitment shows cognitive attachment between an employee and his or her organization because of the costs associated with leaving the organization. Finally, normative commitment refers to typical feelings of obligation to remain with an organization.[5]

Studies have shown that employee's commitment to the organization can aid higher productivity.[6,7,8] It is also an important attitude for evaluating employees’ intention to quit or remain with a cumulative contribution to the organization.[8,9] Employees with more affective commitment are found to be motivated to higher levels of performance and make more meaningful contributions than employees who express continuance or normative commitment. They indicated that staying with the organization was something they wanted to do.[10] Organizational commitment is an important issue to achieve higher quality health care services and is linked to the job satisfaction among providers.[6] Organizational commitment is a major concept in the understanding of employee's behaviors at workplace. Hence, it is useful for the organization to consider human feelings and attitudes. There is a growing evidence to confirm the impact of organizational commitment as an outcome variable in an organization.[11,12,13] Therefore, a lack of commitment among the staff can be harmful to the organization, resulting in poorer performance and higher costs.[14]

Along with organization commitment (OC), intrinsic motivation of workforce is also important. Motivation at work is the perception of a link between efforts and rewards. People are motivated by what they regard as likely impact of their action. Individual examines the prospect of rewards that might arise from different courses of action and decide to act in the way that is most likely to be successful and produce the greatest reward for them personally.[15]

Physician satisfaction and motivation at workplace have been found to be strongly correlated with the quality of care delivered.[16] High physician satisfaction is also likely to result in a good outcome for patient’ health care. Over the years, it has been seen that our health care workers are not satisfied with their professional lives. An unhappy or frustrated mind definitely tries to show his dissatisfaction on his patients.[17]

In recent time, the importance of motivated human resource in the health sector is increasingly realized by policy makers in the international organizations. Contractual character of employment under the National Rural Health Mission in India is now being associated with an increasing number of problems. Renewal of contracts, poor service conditions, no increments, high turnover rate, reluctance to send them for longer skill-based training, and unnecessary and retrogressive hierarchy between the contractual and the permanent staffs are some of the problems reported in the Common Review Mission Reports.[18,19]

For last two decades in India, contractualization of human resource is in practice. What is commitment level of such staff working on contract? How much human resource in the health sector is motivated? If we do not understand these issues and keep on reinforcing contractual model of human resource, there is a possibility of bigger threat and challenges: That is what we are facing for human resource for health. Before contractual model of human resource is fully institutionalized, there is a need to develop a scientific perspective of this model. Keeping these issues in consideration, the present study was undertaken to empirically investigate the assessment and relationship between organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation of the Primary Health Care providers (HCPs) in New Delhi, India.

Materials and Methods

Study was conducted in the Primary Urban Health Centers of Delhi in 2013 among the regular and contractual medical officers (MOs), auxiliary nurse and midwife (ANMs), and pharmacist and laboratory technicians (LTs)/laboratory assistants (LAs) using multistage simple random sampling design. Sample size of 333 primary HCPs includes MO (101), ANMs (114), pharmacists (85), and LTs and LAs (33) under regular and contractual provisions. The sample size was calculated on the basis of 10% of the cadre strength for each category of personnel. Data were collected using the pretested structured questionnaire of 8 items for OC and 34 items for job satisfiers. Intrinsic job motivation was assessed by 6-item tool of modified Warr et al.[20] Data were analyzed by using SPSS version 18 developed by IBM Corporation and appropriate statistical tests such as one-way ANOVA, independent t-test, and regression analysis were applied. In the study, 0.05 level of P value is considered statistical significant.

Reliability of OC and intrinsic motivation instrument was calculated by Cronbach's alpha score which is 0.649 and 0.678, respectively. Content validity of scale was established by experts in the field area.

Results

OC is a psychological state that binds the individual to the organization. It is measured in the study by eight statements of commitment to the organization. Responses to statements are recorded in the form of agree and disagree. Score 0 is loaded to response disagree and score 2 is loaded to response agree. The mean score of OC and standard deviation (SD) are calculated for regular and contractual groups.

Majority of regular HCPs are in age group of 35 years and above. The age of contractual HCP is <35 years. Job experience of the regular staff is more than 10 years whereas majority of contractual staff is having <5 years of experience in the study population.

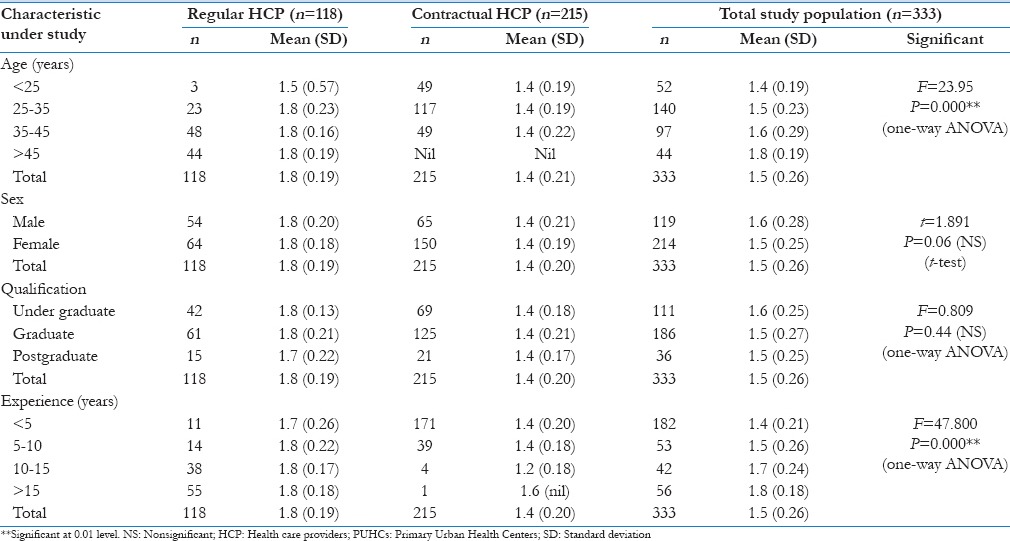

The level of OC of entire study population across different age groups shows statistically significant difference (F = 23.95; P = 0.000). Findings show relatively more OC in older age group. It appears that HCP gradually internalizes the realities of organization and their reactions to adversities decline gradually with age and more committed to the organization. This speculation is fully supported when data were analyzed on experience span of workforce. The OC of entire study population across different job experience shows significant differences (F = 47.80; P = 0.000). However, gender and educational qualification do not show any significant difference in job satisfaction (P > 0.05) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background profile and mean score of organizational commitment of regular and contractual health care providers in the Primary Urban Health Centers

These findings emerged when OC data were analyzed by pooling both regular and contractual staff. In order to get a comparison between regular and contractual staff, findings suggested that regular staff is relatively more committed than contractual staff.

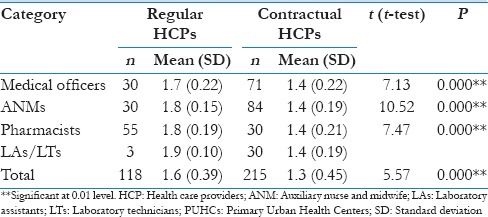

The mean score for OC for entire regular staff is 1.6 (SD: 0.39) and contractual staff is 1.3 (SD: 0.45) which has statistically significant difference in OC (t = 5.57 and P = 0.00). OC score among regular and contractual MOs is 1.7 (SD: 0.22) and 1.4 (SD: 0.22), respectively, with t = 7.13 and P < 0.001. Similar findings were observed among regular and contractual ANMs and LAs/LTs with significant differences (P < 0.001). Regular staff was more committed to the organization than contractual staff as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative mean score of organization commitment among different categories of regular and contractual health care providers in the Primary Urban Health Centers

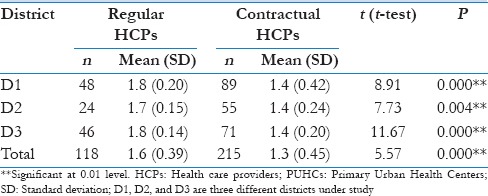

All the three districts under study in New Delhi show significant OC differences among regular and contractual staff as P < 0.001 as shown in Table 3. This denotes that OC is almost same across all the districts among regular as well as among contractual staff. Conditions related to OC do not have any significant differences in the districts among all categories of regular as well as in contractual HCP [Table 3].

Table 3.

District-wise comparative mean score of organization commitment among entire regular and contractual health care providers in the Primary Urban Health Centers

Different types of HCP under regular categories such as regular MOs and regular ANMs, regular ANMs and regular pharmacists, and regular MOs and regular pharmacists showed no significant differences as P > 0.05. Similarly, the study found no significant differences for OC of different categories of contractual staff among themselves as P > 0.05.

The mean OC of regular male and regular female HCP was not significant. Similarly, male and female contractual HCP showed no significant difference in job satisfaction as P > 0.05.

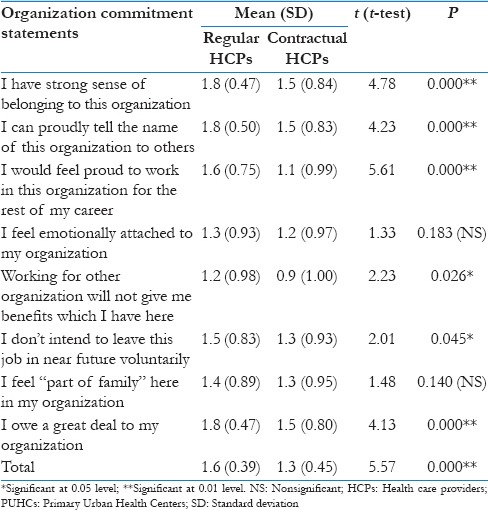

The detailed results of OC for different variables between regular and contractual HCPs are given in Table 4. The mean score of OC for regular HCP is 1.6 (SD: 0.39) and contractual is 1.3 (SD: 0.45), indicating contractual HCPs are less committed to the organization in comparison to regular (P = 0.000). In both regular and contractual HCPs, none of them have a significant difference in emotional attachment with the organization and feel part of family in the organization as P > 0.05. Contractual HCPs do not feel proud to work in the present organization for rest of their career, and this is significantly low in contractual staff in comparison to regular HCPs (t = 5.61; P = 0.000) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparative mean score of different variables of organization commitment for entire regular and contractual health care providers in the Primary Urban Health Centers

Type of job whether regular or contractual alone explains 44.7% of variance in the organizational commitment of HCPs at significance level of 0.01 level (R2 = 0.447; β = 0.669; P = 0.000). Duration of job (experience) of HCPs explains 29.0% of variance in OC (R2 = 0.290; β = 0.538; P = 0.000). Salary and allowances, job security, working environment, appreciation of work, and career growth explains 16.9% of variance in OC of HCPs (R2 = 0.169; P = 0.000).

Other predictors of OC are training in job, independence at workplace, physical working conditions, pensionable job, and children education facilities in the organization. These entire factors have a positive correlation with OC of HCPs (P < 0.05). The findings strongly suggest that the mode of entry of employee and privileges in the organization contribute substantially to the OC.

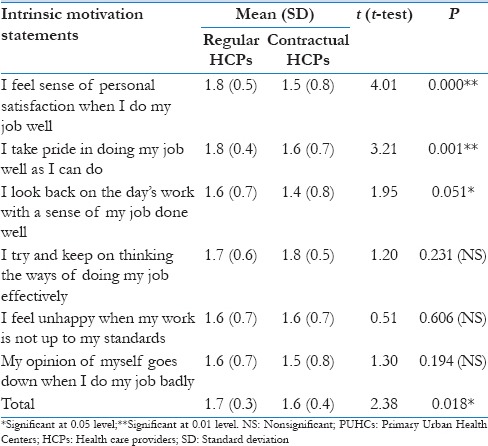

Intrinsic job motivation is defined as the degree to which a job holder is motivated to perform well in his work because of his inner drives. It is measured in this tool with the response in the form of agree or disagree. Disagree is give 0 score, and agree response is give 2 scores. Mean scores with SD are calculated for regular and contractual HCPs in the study population and are shown in Table 5. Mean score of regular HCPs is 1.7 and contractual is 1.6 both are more than 1.0 (mean of score) indicating that intrinsic motivation is high in both groups but intergroup difference is significant (t = 2.38; P < 0.05) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparative mean score of different variables of intrinsic motivation for entire regular and contractual health care providers in the Primary Urban Health Centers

Intrinsic motivation of various categories of regular HCPs such as MOs, ANMs, pharmacists, and LAs/LTs among themselves is not significant (P > 0.05). However, contractual providers show significant difference among themselves (F = 3.537; P = 0.016). Post hoc Tukey's test revealed that contractual MOs are more motivated than the contractual ANMs.

There is a significant difference for intrinsic motivation between various categories of HCPs such as MOs, ANMs, pharmacists, and LAs and LTs (F = 5.508; P = 0.001). Further post hoc Tukey's was applied to see which group has more IM which revealed that entire MOs in the study have higher IM than entire ANMs and difference was significant (P < 0.01).

Different age groups revealed no significant difference for intrinsic motivation (F = 1.479; P = 0.220). Similarly, gender wise no significant difference in intrinsic motivation (t = 1.330; P = 0.184). There was significant difference in IM for education level; graduates HCP were more motivated than undergraduates HCP (F = 3.503; P = 0.05). Older HCP were more motivated than younger group (F = 3.464; P = 0.01).

Type of job whether regular or contractual along with experience (duration of job) and age of HCPs explains only 4.5% of the variance in the intrinsic motivation of HCPs at a significance level of 0.05 (R2 = 0.045; P = 0.05).

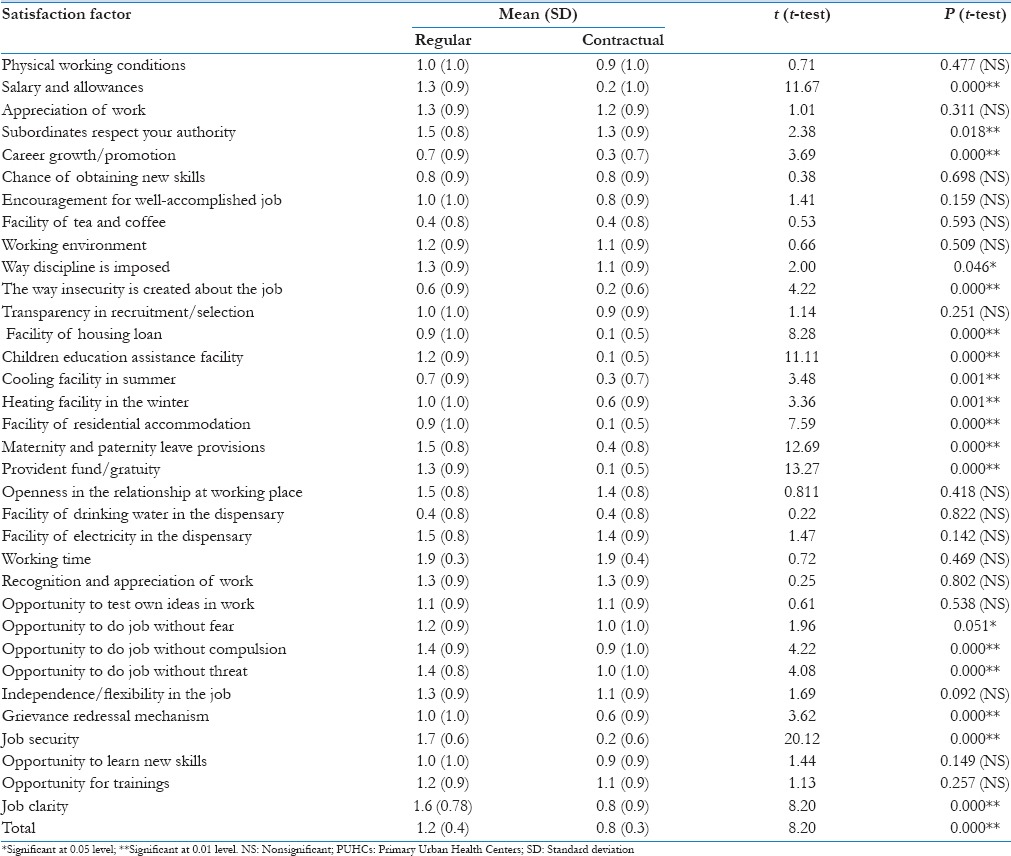

All the respondents were asked to give responses for job satisfier and dissatisfier from already listed 34 factors in the questionnaire. Some of the variables in the list were: Physical working conditions, salary and allowances, appreciation of work, career growth/promotion, encouragement for well-accomplished job, recognition and appreciation of work, independence/flexibility in the job, and openness in the relationship at working place, etc. Score 0 was given to dissatisfier factor in the organization among the list, and score 2 was given to satisfier factor. Mean score and SD were calculated for regular and contractual HCPs. Mean score of satisfier in the regular group is 1.2 and contractual group is 0.8. Contractual group have more dissatisfier and difference is significant as P < 0.01 as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparative mean score of different satisfaction factors among entire regular and contractual health care providers in the Primary Urban Health Centers

Pearson correlation coefficient between OC and intrinsic motivation showed no relationship (r = 0.056; P = 0.306). Pearson correlation coefficient between satisfaction factor and OC is significant (r = 0.386; P = 0.01) indicating that satisfied workforce is more committed to the organization. There is no association between intrinsic motivation and job satisfier factor (r = 0.067; P = 0.221). This means if providers are satisfied in the organization it does not mean that they will be motivated also.

Discussion

OC of HCPs is dependent on age. HCPs having older age have significant higher OC. Providers who are at senior positions and have experience of more than 15 years are more committed to the organization in comparison to less experienced staff and difference is statistically significant. These finding were supported by a study conducted by Khanifar et al.[21] and Mosadeghrad and Ferdosi[22] in Iran. Different education level and gender show no significant difference in OC levels of health providers and similar results were reported in a study conducted in Iran hospitals.[22]

Meyer et al. reported that binding forces of commitment are experienced as a mindset (i.e., a frame of mind or psychological state that compels an individual toward a course of action).[5] In the study, there is a significant difference for OC between regular and contractual providers in primary health care system. Similar finding of poor organizational commitment was reported by Bernhard-Oettel et al.[23] and Mosadeghrad and Ferdosi[22] in Iran. Commitment is dependent on the type of job (regular or contractual) and experience of providers in the organization. In both the groups in present study none have a high emotional attachment with the organization and they do not feel part of family in the organization therefore affective commitment is very low. The study has revealed a positive relationship between job satisfaction and OC. These findings are supported by Abraham and Herzberg theory indicating that satisfied workforce will be more committed to the organization.[24,25,26] Entire HCPs have high intrinsic motivation, and regular staff is more motivated than contractual staff. There is no relationship between job satisfaction factors and intrinsic motivation. This means human resource may be motivated but they are not satisfied from the work culture of the organization. These findings differ from an earlier study conducted by Kavanaugh et al. which reported that low job satisfaction leads to low motivation.[27,28] Findings are also against the theory of Abraham[24] and Herzberg.[25]

Conclusion

From the findings and discussion, it is concluded that intrinsic motivation and organizational commitment of contractual employees is lesser than the permanent employees in the organization. This is a serious issue of concern for health managers and policy makers of Indian health care system. Contractual staff has more dissatisfiers in the organizations comparatively. This would lead to reduced efficiency and effectiveness of the organization. Therefore, it is suggested that appropriate changes are required in the predictors of organizational commitment and factors responsible for satisfaction in the organization. Changes at policy level are suggested to include the entire factor responsible for commitment and satisfaction of human resource in the policies and practices of human resource management to keep the contractual human resource motivated and committed to the organization for fruitful results in the health care system of India.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mosadeghrad AM, Ferlie E, Rosenberg D. A study of the relationship between job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health Serv Manage Res. 2008;21:211–27. doi: 10.1258/hsmr.2007.007015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingersoll GL, Olsan T, Drew-Cates J, DeVinney BC, Davies J. Nurses’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and career intent. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32:250–63. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redfern S, Hannan S, Norman I, Martin F. Work satisfaction, stress, quality of care and morale of older people in a nursing home. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10:512–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kate W, Masako T. Reframing Organizational Commitment within a Contemporary Careers Framework. New York: Cornell University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnyutsky L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav. 2002;61:20–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner CM. Organizational commitment as a predictor variable in nursing turnover research: Literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:235–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parry J. Intention to leave the profession: Antecedents and role in nurse turnover. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64:157–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riketta M. Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. 2002;23:257–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rynes SL. Where do we go from here. Imagining new roles for human resources? J Manage Inq. 2004;13:203–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer TN, Erdogan B, Liden RC, Wayne SJ. A longitudinal study of the moderating role of extraversion: Leader-member exchange, performance, and turnover during new executive development. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91:298–310. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finegan JE. The impact of person and organizational values on organizational commitment. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2000;73:149–69. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallie D, Felstead A, Greed F. Employer policies and organizational commitment in Britain 1992-1997. J Manage Stud. 2001;38:1081–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hersey P, Blanchard KH. Management of Organizational Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources. 6th ed. US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flood P, Turner T, Ramamoorthy N, Pearson J. Causes and consequences of psychological contracts among knowledge workers in the high technology and financial services industry. Int J Hum Resour. 2001;12:1152–65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vroom VH. Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horowitz CR, Suchman AL, Branch WT, Jr, Frankel RM. What do doctors find meaningful about their work? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:772–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-9-200305060-00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fifth Common Review Mission Report. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India, Nirman Bhawan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sixth Common Review Mission Report. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India, Nirman Bhawan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warr P, Cook J, Wall T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. J Occup Psychol. 1979;52:129–48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanifar H, Hajlou MH, Abdolhosseini B, Ataei F, Soltani H. Factors affecting the organizational commitment of employees and customer satisfaction. J Basic Appl Sci Res. 2012;2:1180–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosadeghrad AM, Ferdosi M. Leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in healthcare sector: Proposing and testing a model. Mater Sociomed. 2013;25:121–6. doi: 10.5455/msm.2013.25.121-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernhard-Oettel C, Isaksson K, Bellaagh K. Patterns of contract motives and work involvement in temporary work: Relationships to work-related and general well-being. Econ Ind Democracy. 2008;29:565–91. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraham HM. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50:370–96. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herzberg F. The motivation hygiene concept and problems of manpower. Pers Adm. 1964;26:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alhaji IA, Yusoff FB. Does motivational factor influence organizational commitment and effectiveness. A review of literature? J Bus Manage Econ. 2012;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kavanaugh J, Duffy JA, Lilly J. The relationship between job satisfaction and demographic variables for healthcare professionals. Manage Res News. 2006;29:304–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galletta M, Portoghese I, Battistelli A. Intrinsic motivation, job autonomy and turnover intention in the Italian healthcare: The mediating role of affective commitment. J Manage Res. 2011;3:1–19. [Google Scholar]