Abstract

Payment to recruit research subjects is a common practice but raises ethical concerns relating to the potential for coercion or undue influence. We conducted the first national study of IRB members and human subjects protection professionals to explore attitudes as to whether and why payment of research participants constitutes coercion or undue influence. Upon critical evaluation of the cogency of ethical concerns regarding payment, as reflected in our survey results, we found expansive or inconsistent views about coercion and undue influence that may interfere with valuable research. In particular, respondents appear to believe that coercion and undue influence lie on a continuum; by contrast, we argue that they are wholly distinct: whereas undue influence is a cognitive distortion relating to assessment of risks and benefits, coercion is a threat of harm. Because payment is an offer, rather than a threat, payment is never coercive.

Keywords: coercion, undue influence, payment

The practice of paying research participants – whether they are healthy volunteers or patient volunteers – evokes controversy within the research community. While some deem payment an appropriate means of compensating or incentivizing research participants, others contend that monetary offers may undermine the voluntariness of participants’ informed consent in light of their potential to coerce or unduly influence.1 The US ‘Common Rule’ for the Protection of Human Subjects offers little guidance to individuals seeking to reconcile these conflicting viewpoints, stating simply:

An investigator shall seek such consent only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject or representative sufficient opportunity to consider whether or not to participate and that minimize the possibility of coercion or undue influence.

To a considerable extent, then, IRB members – the crucial gatekeepers of the research enterprise – are left largely to their own devices as they interpret and apply these difficult concepts.

We conducted the first national survey of IRB members and human subjects protection professionals that seeks to explore their attitudes as to whether and why payment of research participants constitutes coercion or undue influence.2 As we reported elsewhere, the majority of respondents expressed concern that payment in any amount might influence research participants’ decisions or behavior. To the extent that IRB members’ attitudes regarding coercion and undue influence are ethically sound, they appropriately influence payment practices, as studies should not be approved if participants’ consent is likely to be compromised. If, however, IRB members’ concerns are based on conceptual or ethical misconceptions, unnecessary limits may be placed on payments to research participants and impede valuable research without ethical cause.

The purpose of this article is to show that these prevalent concerns about payment are largely misguided. We distinguish coercion and undue influence and argue that payment never coerces. We defend the view that payment raises ethical concerns about the validity of consent only when it unduly influences participants by distorting their perception of research risks and benefits. In the absence of evidence that such distortions occur, IRBs should be reluctant to conclude that offers of payment undermine the validity of consent.

ATTITUDES TOWARD PAYMENT

Lacking systematic evidence about the views of IRB members and research ethics professionals, we undertook a national survey to discover how they think about payment, coercion, and undue influence.3 A more extensive description of the survey methods and findings has been published elsewhere.4 In brief, our 2010 study was a web-based survey of 1380 individuals randomly selected from the database of Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research (PRIM&R). The database contains members of PRIM&R and others who self-identified as interested in IRBs and human subjects protection (see Table 1). The survey, which is available on request, consisted of 80 questions, the majority of which were closed-end, though several opportunities to make open-ended comments were also provided.

Table 1.

Respondent Characteristics

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 403 | 70% | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 479 | 84% | |

| Age | 50.5 ± 11 | ||

| Master's Degree | 148 | 26% | |

| Advanced/Doctoral Degree | 223 | 39% | |

| Census Region | |||

| Northeast | 155 | 25% | |

| South | 232 | 38% | |

| Midwest | 107 | 18% | |

| West | 104 | 17% | |

| Current Role Related to Human Subjects Research* | |||

| IRB Member | 222 | 68% | |

| Researcher | 157 | 26% | |

| Academic, Non-Researcher | 79 | 13% | |

| Clinician, Non-Researcher | 46 | 8% | |

| Research Nurse | 21 | 3% | |

| Ethicist | 58 | 10% | |

| Sponsor | 13 | 2% | |

| Regulator | 122 | 20% | |

| Evaluate Grants | 67 | 11% | |

| Write Policy | 120 | 20% | |

| Other | 209 | 34% | |

| None | 42 | 7% | |

Respondents could select more than one role. Demographic questions were answered by 579 of the 610 respondents.

At the most general level, our respondents had ethical concerns about the offer of payment to research subjects. Respondents’ views on the acceptability of payment differed somewhat depending on the reasons for payment (see Table 2). Whereas almost all agreed that researchers could offer money for reimbursement of expenses or as compensation for time and inconvenience, just over one-third of survey respondents regarded it as acceptable to offer payment as compensation for risk. As one respondent put it, ‘I do not think that risk is a valid reason to reimburse people.’ We are not surprised that respondents were more sympathetic to reimbursing subjects for expenses or to compensating them for time, effort, and inconvenience as contrasted with compensation for risk, particularly given that some institutional regulations specifically state that IRBs should not regard payment as a benefit that offsets risk when making risk/benefit assessments.5

Table 2.

Acceptability of Payment Depending on the Reason for Payment

| Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Disagree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Researchers should be permitted to offer money as reimbursement for research-related expenses – for example, travel and lodging . . . | Healthy Volunteers | 98% | 1% | 1% |

| Patient Volunteers – No Prospect of Direct Benefit | 96% | 2% | 2% | |

| Patient Volunteer – Prospect of Direct Benefit | 94% | 3% | 3% | |

| Researchers should be permitted to offer money as compensation for effort, time, or inconvenience . . . | Healthy Volunteers | 94% | 2% | 4% |

| Patient Volunteers – No Prospect of Direct Benefit | 91% | 7% | 2% | |

| Patient Volunteer – Prospect of Direct Benefit | 87% | 5% | 8% | |

| Researchers should be permitted to offer money as an incentive to participate in research . . . | Healthy Volunteers | 58% | 12% | 30% |

| Patient Volunteers – No Prospect of Direct Benefit | 57% | 12% | 31% | |

| Patient Volunteer – Prospect of Direct Benefit | 51% | 15% | 34% | |

| Researchers should be permitted to consider the offer of money as compensation for risk or as a benefit in risk-benefit assessment . . . | Healthy Volunteers | 37% | 10% | 53% |

| Patient Volunteers – No Prospect of Direct Benefit | 38% | 11% | 51% | |

| Patient Volunteer – Prospect of Direct Benefit | 35% | 14% | 51% |

Use of payment as an incentive divided the group more evenly; only slightly more than half agreed it was permissible to offer money as an incentive to participate, perhaps because some view incentives as a form of coercion or undue influence. As one respondent remarked, ‘At our facility, the PI [Principal Investigator] is not allowed to use the term incentive for payment. That implies coercion.’ Another respondent remarked, ‘Our responsibility is to make sure subjects who participate in research are safe and their decisions to participate are their own. People who decide to be part of a clinical trial should not base their decisions on financial incentives.’

Three points can be made about these views. First, it is dubious to draw a sharp distinction between (1) payment as reimbursement for expenses or as compensation for time, effort, and inconvenience and (2) payment as an incentive. Although the motivations for offering payment may be different, it is reasonable to suppose that prospective subjects are unlikely to make such fine distinctions and are more likely to participate if they are offered payment for any reason than if they are not. In that sense, payment as reimbursement or compensation effectively incentivizes prospective subjects to enroll. Second, offering payment as an incentive does not conflict with individuals making ‘their own’ decisions to participate in research. After all, earning money might be some prospective subjects’ most important reason to participate.6 It may be ‘their own’ autonomous choice. Third, it is not clear why an offer of payment made as an incentive should be more likely to constitute coercion or undue influence than payment made for other reasons. Indeed, we shall argue below that payment never constitutes coercion and only constitutes undue influence under limited circumstances.

COERCION AND UNDUE INFLUENCE

To probe respondents’ understandings of coercion and undue influence, we first asked them whether they agreed with abstract formulations of coercion and undue influence and then whether they thought subjects were coerced or unduly influenced in several hypothetical scenarios (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of abstract views about coercion and undue influence

| % of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that if the research participants ... | Then . . . it is coercion | Then . . . it is undue influence |

|---|---|---|

| . . . are threatened with harm | 91.2% | – |

| . . . will participate when otherwise they would not if offered payment | 64.8% | 81.0% |

| . . . feel they have no reasonable alternative but to participate because offered payment | 81.6% | 79.2% |

| . . . ability to accurately perceive risks and benefits is distorted when offered payment | – | 98.2% |

| % of respondents that thought the individuals in the hypothetical situations | Were coerced | Were unduly influenced |

|---|---|---|

| Mary: ‘I would not normally have enrolled, but I recently lost my job and need the money. I don't feel like I have any alternative . . ’ | 24.3% | 64.4% |

| John: ‘The bills have piled up since I got sick and I feel like my only option is to participate . . . I need the money’ | 26.7% | 70.2% |

| Steve: ‘I don't have health insurance. I don't care about the money, but by enrolling in this study I get the medical care I need. I feel like I have no alternative’ | 26.5% | 60.5% |

Coercion

How do and how should IRB members understand coercion? The Belmont Report, upon which many rely for authoritative guidance, states, ‘Coercion occurs when an overt threat of harm is intentionally presented by one person to another in order to obtain compliance.’7 It is worth emphasizing that this definition states that coercion requires: (1) a threat of harm and (2) that the threat comes from another person – as contrasted with background conditions. We attempted to discover whether respondents endorsed this view by asking whether they agreed with the following statement: ‘Research subjects are coerced only if they are threatened with harm if they don't participate in research’ (emphasis added). Although 91% agreed, we suspect that most read the question as asking whether they thought someone is coerced ‘if’ rather than ‘only if’ they are threatened with harm because our respondents also agreed with abstract formulations of coercion that do not involve a threat of harm. For example, 61% said that they were concerned about the potential for coercion when researchers ‘offer substantial payment to subjects’ and, by definition, offers of payment are not threats. Moreover, a majority agreed that research subjects are coerced if the offer of payment makes them participate when they otherwise would not (65%) or when the offer of payment causes them to feel that they have no reasonable alternative but to participate (82%).

Interestingly, when asked to indicate whether hypothetical scenarios illustrated coercion, respondents exhibited considerable inconsistency between their abstract positions and their responses to the scenarios. For example, Mary, described as a resident of an American inner city invited to participate in a Phase 1 malaria vaccine trial, indicated that because she lost her job and needed money, she felt she had ‘. . . no reasonable alternative but to participate.’ Even though 82% agreed with the abstract statement that subjects are coerced if a payment offer makes them feel that they have no reasonable alternative but to participate, only one quarter (24%) agreed that Mary was coerced. Responses to scenarios involving John and Steve, described as enrolling in a leukemia treatment study that offered payment, were very similar. John said he needed the money to pay bills; 27% agreed that John had been coerced. Steve said he had no health insurance and needed to participate in order to get medical care; 27% agreed that Steve had been coerced.

Although somewhat puzzling, this sort of discordance between abstract views of moral concepts and concrete judgments involving the same concepts is not unique. In a similar vein, experimental philosophers have explored the relation between people's views about determinism – the idea that every event is necessitated by antecedent events – and their views about free will and moral responsibility. Shaun Nichols reports that when respondents are given a non-technical description of determinism and asked whether people can be morally responsible in such a universe, many said that they were not morally responsible.8 When given a concrete scenario in which a person did something terrible in that universe, however, most thought that the person was morally responsible. Since most people have not spent time trying to formulate a definition of coercion, we think that our respondents’ views about the scenarios do a better job of capturing their understanding of coercion than their views about the more abstract formulations. If confronted with the discrepancy, we suspect that most respondents would search for a definition of coercion consistent with their responses to the scenarios rather than revise their views about the scenarios to render them consistent with their more abstract commitments. This is an empirical issue worth exploring.

That said, IRB members should be careful to avoid loose formulations of concepts such as coercion if and when that will lead them to a mistaken judgment that the offer of payment would render a subject's consent invalid and, therefore, to conclude that the IRB should reject a proposed payment scheme. People often use the word ‘coercion’ for rhetorical reasons to express opposition to some practice. For example, one of our respondents expressed feeling ‘coerced’ to participate in our survey by the $5 bill included in our advanced mailing; nevertheless, we doubt that the respondent meant this literally or meant to imply this offer of token payment compromised anyone's consent to participate in our study. This particular hyperbolic use of coercion may be harmless, but if IRB members reject a proposed payment scheme on grounds of coercion (or undue influence) just because people are offered substantial payment to participate, then something has gone seriously wrong. Thus, we should be concerned when a respondent says, ‘Coercion has come to mean something more along the lines of simple influence in the IRBs I have worked with – not the meaning it has in other contexts.’ Not only does this remark raise the question as to whether the meaning of coercion in IRBs should differ from its meaning in other contexts, it also suggests that this respondent's IRB has adopted an excessively expansive account of coercion that may be used inappropriately to limit the activities of researchers and prospective subjects.

Equating coercion with influence, even when the influence is strong, is clearly mistaken. If the offer of payment gets someone to agree to participate in research when they would otherwise not, it surely does not follow that the person has been coerced. There are numerous ways of motivating people to do things that they would otherwise not do, and most of them do not involve coercion or anything morally problematic for that matter. If A persuades B to give blood or go to a movie or invest in a mutual fund when B would otherwise not do so, it is clear that B has not been coerced. The same is true for offers. If A offers the teenager next door $20 to mow his lawn, we would not say that the teenager has been coerced. As a general proposition, offers do not coerce.9 Indeed, if A raised the offer to $50 to get the teenager to agree, we would regard this as a stronger incentive to do the job but still not say that the offer was coercive.

As contrasted with the implausible view that it is coercive to get someone to do something they would otherwise not do, it is somewhat more plausible to say that someone has been coerced to participate in research when they have no reasonable alternative but to consent to participate. Although this abstract formulation was widely endorsed, in the context of the three hypothetical scenarios, approximately one-fourth of respondents endorsed this view. Still, it is important to stress that this view of coercion does not withstand critical scrutiny. While it is true that when people are coerced by a threat of harm they have no reasonable alternative but to comply, it is the threat that is coercive and not the absence of reasonable alternatives. After all, there are many situations in which people choose options because they lack reasonable alternatives without being coerced. We do not say that a patient who agrees to surgery or chemotherapy because the only alternative is death has been coerced to consent or that her consent to treatment is involuntary or invalid.10 Nor do we describe people as coerced if they take an unpleasant job in order to provide for their families. Although these circumstances can be unfortunate, they do not necessarily make the medical care or the employment unfair, and they certainly do not make it coercive.

Wertheimer and Miller have elsewhere defended a ‘rights-violating’ view of coercion, which is similar (although not identical) to the Belmont Report's understanding of coercion.11 On that view, A coerces B to consent to X only if A threatens to violate B's rights if B does not consent. If patients have a right that their physicians not abandon them if they refuse to participate in research, then the implicit or explicit threat of abandonment may constitute coercion. So, too, if a professor threatens students with a lower grade if they do not participate in her study. But such cases involving rights-violating threats aside, we think that coercion to participate in research is probably rare. In sum, IRB members and ethicists should simply stop worrying about the alleged coerciveness of payment. The offer of payment may or may not be objectionable on other ethical grounds, but the offer of payment does not coerce.

Given the implausibility of seeing offers as coercive (and larger offers as more coercive), we can ask why this view has become widespread among IRB members. We suspect that many concerned with the protection of research subjects accept a form of ‘research exceptionalism’ whereby factors that they would not regard as compromising the validity of consent in other contexts are thought to be worrisome in the context of research. We will return to this in the conclusion, but note that this hypothesis deserves further clarification and empirical examination.

Undue influence

Nearly all respondents (98%) agreed that there is undue influence if research participants’ ‘ability to accurately perceive risks and benefits is distorted when offered payment.’ Although we did not ask whether respondents believed that such distortion of judgment is a necessary condition of undue influence, their responses to other items suggests that they do not. With respect to the abstract formulations, 81% agreed that it is ‘undue influence’ if the offer of payment will motivate people to participate ‘when otherwise they would not,’ and 79% agreed if the offer of payment makes prospective subjects feel they have no reasonable alternative but to participate.

Interestingly, although our respondents had very similar views of coercion and undue influence when asked about these abstract formulations (Table 3), when asked about the scenarios, they were much more likely to find undue influence than coercion. With respect to Mary, who needed money and didn't feel that she had any alternative to participating, 24% said she had been coerced, but 64% said she had been subjected to undue influence. A similar pattern held with respect to John whose bills had piled up and felt that his only option was to participate (27% v 70%) and Steve, who didn't need the money but lacked health insurance and enrolled because he felt he had no other way to get the medical care he needed (26% v 60%). It is unclear why the respondents displayed greater discordance between abstract definition and concrete scenarios with respect to coercion than with respect to undue influence, but their views about the scenarios seem to reflect an intuitive reaction rather than the application of any particular definitions of the respective concepts.

Once again, we don't know the extent to which these views actually affect IRB decisions to reject protocols or ask for revisions in proposed payment schedules (or, for that matter, if researchers anticipate these actions and therefore draft their protocols accordingly), although we suspect that they must have some effect. Such views would not be problematic if they reflected a reasonable interpretation of the principle that IRBs should not approve protocols that involve undue influence. In our view, however, they do not. We do not deny that offers of payment can constitute undue influence, but as we noted above, there is nothing inherently problematic in motivating someone to do something that they would otherwise not do or in treating an individual's consent as valid when they have no reasonable alternative but to choose to participate.

How should IRB's understand the concept of undue influence? The concept of undue influence is less familiar than that of coercion. As a matter of ordinary discourse, we routinely talk about coercion, but we rarely if ever say that someone has ‘unduly influenced’ another. As a consequence, and in contrast with coercion, it is more diffi-cult to provide a helpful account of undue influence.12 While accurately defining ‘coercion,’ The Belmont Report merely states that ‘Undue influence, by contrast [with coercion], occurs through an offer of an excessive, unwarranted, inappropriate or improper reward or other overture in order to obtain compliance.’ Unfortunately, this account is not helpful for two reasons. First, it does not specify when or for what reasons an offer should be considered excessive, unwanted, inappropriate or improper. Second, it may conflate ethical worries about offers that concern the validity of consent with what might be called ‘bribery’ or ‘commodification’ worries that maintain that it is improper to offer money for certain services (such as sex) even if the validity of the responder's consent is not in doubt.13 If a driver offers a police officer a bribe not to give him a ticket, the offer is inappropriate, but we do not think that the officer's consent to accept the bribe is invalid. Interestingly, even though Belmont defines undue influence in terms of offers, it proceeds in the next paragraph to state that undue influence would include ‘threatening to withdraw health services to which an individual would otherwise be entitled’. This clearly seems to be a straightforward case of coercion rather than undue influence, and so it remains an open question as to how best to understand non-coercive offers that compromise the validity of consent on grounds of undue influence.

We think that A's offer of payment is best understood as undue influence if it is so attractive that it distorts subjects’ evaluation of the risks and benefits of participation. Whereas coercion compromises the voluntariness of a decision (but not necessarily its rationality), undue influence is best understood as compromising the cognitive dimension of decision-making. Although The Belmont Report does not explicitly endorse the view that offers are unduly influential when they bias the subject's appraisal of risks and benefits of participation, other documents do take that approach. The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) guidebook for IRBs says ‘Offers that are too attractive may blind prospective subjects to the risks or impair their ability to exercise proper judgment.’14 Similarly, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the remuneration of research subjects reads: ‘Although subjects may consider remuneration in their decision about research participation, it should not substitute for nor bias careful attention to the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the study.’15

On these views just described, an offer of payment does not constitute undue influence if subjects are likely to make a reasonable or rational choice to regard the value of the payment as sufficient to justify the risks or burdens of participation. For example, we suspect that most people would agree that a professor is not unduly influenced if the offer of $5,000 to teach a summer school course motivates motivates her to do so or that a structural steel worker who chooses to engage in one of the riskier jobs in the nation is not unduly influenced by his paycheck. As a respondent noted about one of our scenarios, ‘To say that this would be undue influence would be similar to saying that being paid to work is undue influence. This is a legitimate choice John could make given the real circumstances of his life.’ As another respondent put it, ‘Does John fully understand the research? Do we assume that he cannot make a decision even when he realizes that he does not have other sources to earn money? He is influenced, but is it undue influence? I am inclined to think not, assuming that he is a reasonable person.’

To put this line of argument in slightly different terms, it is important to distinguish between two claims:

-

(1)

an offer of payment distorts the subject's judgment such that the subject consents to participate when doing so does not advance his interests, all things considered.

-

(2)

given the subject's objective circumstances, an inducement actually renders it rational for the subject to participate.

An offer of payment to a prospective subject constitutes a morally problematic undue influence only if a subject's response to the offer is irrational or her reasoning is distorted as in (1). It is possible that subjects such as Mary, John, and Steve are making a mistake. It is possible that they are wrong to think that the benefit of payment exceeds the risks of participation; that would depend upon details that we have not provided. But absent a showing that the judgment of subjects is distorted by the offer of financial payment, there is no reason to reject an offer on the grounds of undue influence and thereby preclude subjects from receiving such offers.

Now, it may be morally troublesome that people are in a situation such as (2), but there is no reason to regard the offer of payment as either coercive or constituting an undue influence in such cases – particularly if participation in research in exchange for money may be a prospective subject's best alternative given her objective conditions. As one of our respondents explained, ‘I think protecting poor people from receiving money or medical care is often more unethical than offering payment.’ In this context, it is important to distinguish between genuine paternalism, which protects people from doing what is harmful to them, and what we might call ‘pseudo-paternalism,’ which prohibits people from doing what is actually in their interests by their own reasonable lights. Paternalism can be justified when people suffer from decisional deficiencies and are unable to make reasonable choices. If the offer of payment has such distorting effects, then IRBs should regard the offer as undue influence.16 Unfortunately, we suspect that the application of mistaken conceptions of undue influence may sometimes lead IRBs unwittingly to prevent people from participating in research in exchange for payment when doing so is genuinely in their interests because they reasonably regard the value of payment as greater than the risks of participation.

Distinguishing between coercion and undue influence

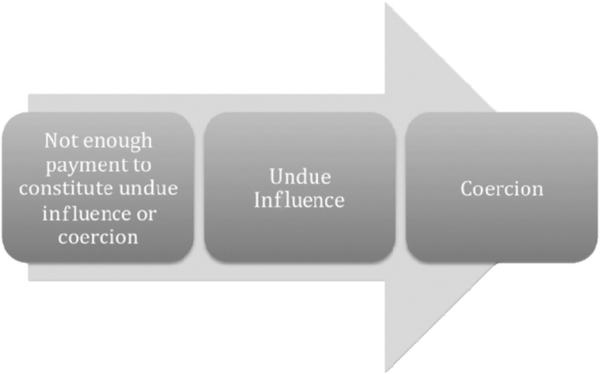

As we have shown, although our respondents were almost as likely to find coercion as undue influence in the abstract formulations of the two concepts, they clearly perceived a distinction between coercion and undue influence as they were much more likely to find undue influence than coercion in our hypothetical scenarios. Although we did not ask them how they made this distinction, our reading of their responses to the survey questions and their open-ended comments suggests that (consciously or unconsciously) many respondents understand coercion and undue influence as lying on a continuum (Figure 1). As one of our respondents put it: ‘I take undue influence and coercion to stand on a sliding scale. The former is a milder form of the latter.’ On what we will call the ‘sliding scale view,’ the quantity of payment is directly correlated with the ‘pressure’ on the decision-maker, and the threshold of pressure necessary to constitute undue influence is less than the threshold of pressure necessary to constitute coercion.

Figure 1.

The ‘Sliding Scale’ View of Coercion and Undue Influence.

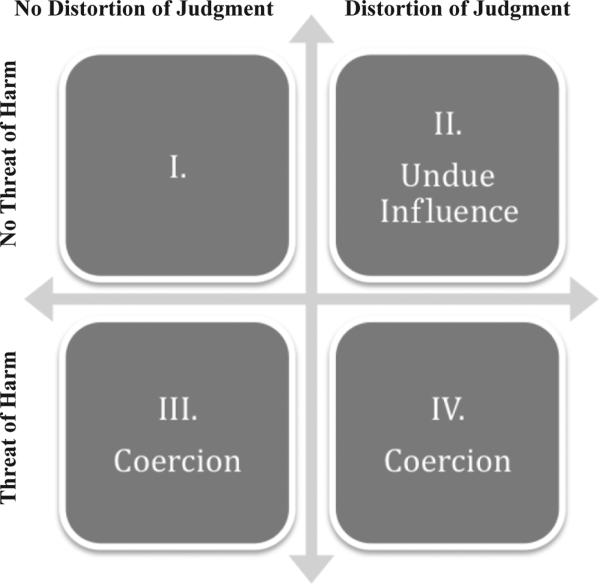

The sliding scale view has intuitive appeal and may be implied by some of the canonical statements, which mention coercion and undue influence together and fail to draw a conceptual distinction between them. Nonetheless, we maintain that although both coercion and undue influence render consent invalid, they do so in ways that are quite distinct. On what we call the ‘distinct concept view,’ coercion and undue influence represent distinct cross-cutting variables (Figure 2). Coercion compromises the voluntariness of consent by the threat of harm, whereas undue influence compromises the validity of consent by creating a cognitive deficiency or distortion in reasoning. The target of coercion may act involuntarily but perfectly rationally as when an individual quite sensibly decides to turn over his wallet to a man brandishing a knife. By contrast, individuals who are unduly influenced may act voluntarily, but their reasoning is distorted.

Figure 2.

The ‘Distinct Concept View’ of Coercion and Undue Influence.

We argued above that the offer of payment is not coercive because it does not involve the threat of harm. So if we eliminate the ‘coercion’ quadrants (III and IV) as irrelevant to payment, then IRBs should conclude that the offer of payment compromises the validity of a subject's consent only if the subjects’ decision-making is distorted as in quadrant II. Once again, there may be other reasons to think that payment is or is not appropriate, and there may be other grounds on which the validity of a subject's consent may be questionable, such as the therapeutic misconception. But so long as the offer of payment lies in quadrant I, there is no reason for IRBs to think that such offers compromise the validity of consent.17

CONCLUSION

If our argument is on the right track, then our survey has demonstrated that many IRB members hold indefensible views about payment, coercion, and undue influence. As we have said, we do not know the extent to which the views of IRB members about payment actually affect their decisions on protocols or the extent to which researchers do not propose payment schedules that they believe will be rejected by IRBs for such reasons. If, as seems likely however, these views do affect the decisions of IRBs, they would inappropriately limit payment offered to research subjects and could thereby slow the pace of valuable clinical research for invalid reasons. Additionally, and importantly, decisions based on those views would also deny prospective subjects opportunities to participate in research from which they would benefit or prohibit them from receiving payment even if they are otherwise prepared to enroll. As a general proposition, we should be very careful before we interfere with what seem to be win-win-win propositions for researchers, prospective subjects, and those who stand to benefit from research.

Our analysis poses the question as to why IRB members are so likely to have misconceptions about coercion and undue influence. We suggested above that this pseudo-paternalism may reflect what we called ‘research exceptionalism’. Crudely put, many concerned with research ethics are much ‘fussier’ about what constitutes valid consent to participate in research than about what constitutes valid consent in other areas of life such as employment. What might make research appear different in this respect? In general, research often exposes research subjects to risks for the benefit of society as contrasted with other areas of life where people typically consent because doing so is in their self-interest. Viewed through this lens, it is quite appropriate for altruistic individuals to volunteer for research that exposes them to risks without compensating medical benefits but worrisome if individuals agree to participate for the sake of payment. From this perspective, it may make sense to be more careful about what constitutes valid consent to participate in research than in other domains and to be concerned as to whether providing payment to participate in research unjustifiably puts subjects at risk.

Given that there is a tradition of research ethics that claims that participation should always be altruistic and, at its best, that participants should identify with the purposes of the study, it is not surprising that some IRB members will find it unseemly to introduce payment into the research equation.18 That said, such justifiable caution about payment does not warrant misconceiving and mis-applying the concepts of coercion and undue influence. Even if offering payment to research subjects is unseemly – and we do not agree that it is – it does not follow that such offers compromise the validity of a subject's consent. If, as in other contexts of life, people can reasonably regard the value of payment as greater than the risks of engaging in some activity, be it ordinary employment or participation in research, then we do not protect subjects when we mistakenly preclude their activity on grounds of coercion or undue influence.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, the Public Health Service or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Emily Largent was a fellow in the NIH Department of Bioethics from 2008–2010 and is currently a candidate in the PhD Program in Health Policy at Harvard University. Her research focuses on ethical issues in clinical research and medical charity.

Christine Grady is the Acting Chief of the Department of Bioethics at the NIH Clinical Center. Her research interests include the ethics of paying research participants and related issues of recruitment and consent.

Franklin G. Miller, PhD is on the senior faculty in the Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health. He has written or edited six books and numerous published articles on the ethics of clinical research, ethical issues concerning death, dying, and organ donation, professional integrity, health policy, and the placebo effect.

Alan Wertheimer, PhD is Senior Research Scholar, Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, USA and Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Vermont. He is the author of Rethinking the Ethics of Clinical Research: Widening the Lens (Oxford University Press, 2010), Consent to Sexual Relations (Cambridge University Press, 2003), Exploitation (Princeton University Press, 1996) and Coercion (Princeton University Press, 1987).

References

- 1.Grady C. Money for Research Participation: Does it Jeopardize Informed Consent.? Am J Bioeth. 2001;1(2):40–44. doi: 10.1162/152651601300169031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, Klitzman R. Voluntariness of Consent to Research: A Conceptual Model. Hastings Cent Rep. 2009;39(1):30–39. doi: 10.1353/hcr.0.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Largent E, et al. Money, Coercion, and Undue Inducement: Attitudes about Payments to Research Participants. IRB: Ethics & Human Research. 2012;34(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.See also Ripley E, et al. Why do We Pay? A National Survey of Investigators and IRB Chairpersons. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5(3):43–56. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.43.Ripley E, Macrina F, Markowitz M. Paying Clinical Research Participants: One Institution's Research Ethics Committees’ Perspective. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics. 2006;1(4):37–44. doi: 10.1525/jer.2006.1.4.37.

- 4.Largent op. cit. note 2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH Office of Human Subjects Research (OHSR) [17 Feb 2012];Sheet 20 – Guidelines for remuneration of research subjects in the intramural research program and registration in the clinical research volunteer program database. 2011 Jul; Available at: http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/sheet20.html.

- 6.Stunkel L, Grady C. More than Money: A Review of the Literature examining Healthy Volunteer Motivations. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2011;32(3):342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1979. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols S. Experimental Philosophy and the Problem of Free Will. Science. 2011;331(6023):1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1192931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wertheimer A, Miller FG. Payment for Research Participation: a Coercive Offer? J Med Ethics. 2008;34:389–392. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.021857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For a contrary, although mistaken view, see Caplan Arthur. Am I My Brother's Keeper? Indiana University Press; Bloomington IN: 1997.

- 11.Wertheimer, Miller op. cit. note 9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emanuel E. Undue Inducement: Nonsense on Stilts? Am J Bioeth. 2005;5(5):9–13. doi: 10.1080/15265160500244959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wertheimer A. Rethinking the Ethics of Clinical Research. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) [17 Feb 2012];IRB Guidebook. 2011 Jul; Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/archive/irb/irb_guidebook.htm.

- 15.NIH Office of Human Subjects Research (OHSR) op. cit. note 5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wertheimer, Miller op. cit. note 9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appelbaum PS, et al. False Hopes and Best Data: Consent to Research and the Therapeutic Misconception. Hastings Cent Rep. 1987;17(2):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonas H H. Philosophical Reflections on Experimenting with Human Subjects. Daedalus. 1969:98. [Google Scholar]