Abstract

Many constituents of Wnt signaling pathways are expressed in the developing and mature nervous systems. Recent work has shown that Wnt signaling controls initial formation of the neural plate and many subsequent patterning decisions in the embryonic nervous system, including formation of the neural crest. Wnt signaling continues to be important at later stages of development. Wnts have been shown to regulate the anatomy of the neuronal cytoskeleton and the differentiation of synapses in the cerebellum. Wnt signaling has been demonstrated to regulate apoptosis and may participate in degenerative processes leading to cell death in the aging brain.

Introduction

Wnt proteins (the name is derived from mouse Int-1 and Drosophila wingless) are a large family of signaling molecules that have well-established roles in regulating embryonic patterning, cell proliferation and cell determination [1,2•]. There are a total of 24 known vertebrate Wnts, with 18 identified in the mouse [3]. They interact with members of the Frizzled family of receptors to activate downstream signaling events through at least two distinct pathways, one of which controls gene transcription and the other Ca2+ fluxes [4,5,6•]. To date, 11 members of the Frizzled family have been identified in mice which encode for seven transmembrane domain-containing serpentine receptors. Wnt-mediated signaling is also controlled extracellularly by proteins that either potentiate or inhibit receptor activation. As many wnt proteins and frizzled receptors are expressed in both the developing and mature nervous systems [5], this has stimulated much recent work to examine their roles in both neural development and function. In this commentary, we review recent advances in understanding mechanisms of Wnt signaling. Of particular interest, we discuss the recently discovered elaborate mechanisms developed by metazoan organisms to control spatial and temporal signaling by this important family of molecules. Within the embryonic nervous system, recent work shows that Wnt proteins are involved in almost all important patterning events. Surprisingly, Wnt proteins appear to be equally important at later stages of development and in the mature brain. These observations suggest many productive directions for future research by neuroscientists.

Wnt signaling pathways

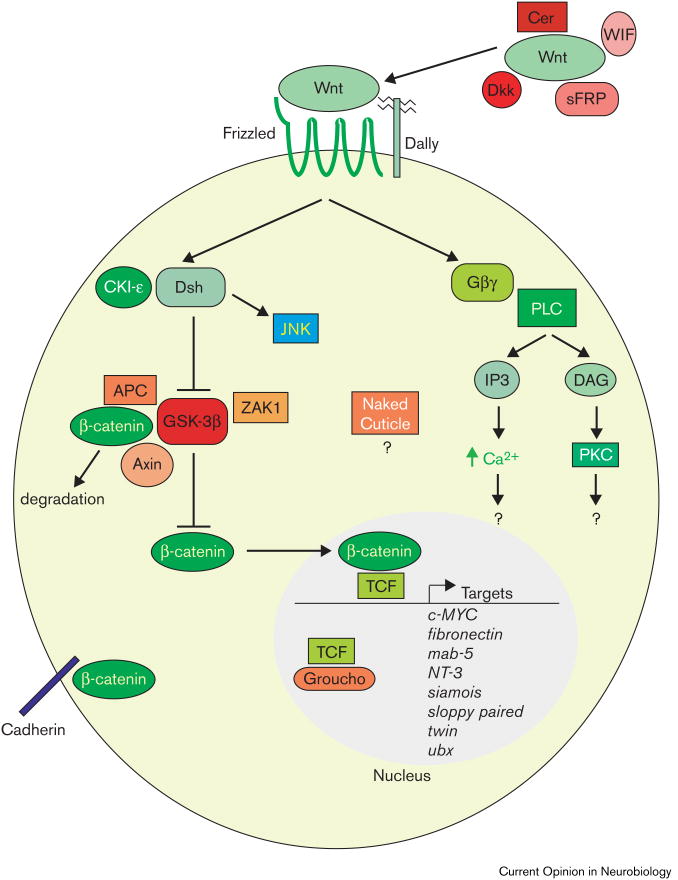

For several years it has been known that many Wnt proteins activate gene transcription through a pathway controlled by β-catenin [1,2•] (illustrated in Figure 1). Wnt protein binding to Frizzled receptors activates Dishevelled. Activation of Dishevelled results in inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β(GSK-3β), which results in stabilization of β-catenin. Free β-catenin forms nuclear complexes with members of the TCF/LEF transcription factor family to regulate expression of numerous genes [6•].

Figure 1.

Model for Wnt signaling. Adapted from the Web pages of Nusse [3]and Moon [72]laboratories. Molecules shown in shades of green are positive regulators of the Wnt pathway, while those shown in red are negative regulators. See manuscript for details.

In the absence of Wnt signaling, β-catenin is associated with a complex including GSK-3 β, Axin and the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein (APC). Phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK-3βresults in its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by proteosomes [7,8•,9,10]. While members of the TCF/LEF family associate with free β-catenin in cells in which there is active Wnt signaling, in the absence of Wnt the TCF/LEF family members associate with Groucho, a transcriptional inhibitor [6•]. Thus TCF/LEF transcription factors have opposing effects on gene expression, depending upon which proteins they are associated with. Complexes of TCF/LEF and β-catenin may cooperate with factors activated by other signaling pathways. Wnt and transforming growth factor β(TGF-β) family member signaling are synergistic, for example, in formation of Spemann's organizer. There it has recently been shown that β-catenin and LEF-1/TCF form a complex with Smad4, a transcription factor involved in TGF-βsignalling, and promote translocation of Smad4 to the nucleus where they cooperatively control expression of a Wnt target gene twin [11•]. In other instances Wnt and TGF-βfamily-dependent signaling are antagonistic. The nature of the interactions must depend upon cellular context.

Recent work has identified additional protein kinases that act both upstream and downstream of β-catenin. Casein kinase I-ε (CkIε) has been shown to form a complex with Dishevelled, Axin and GSK-3β[12•]. It functions to stabilize β-catenin and to activate β-catenin-dependent signaling pathways. Thus it appears to be an upstream effector controlling β-catenin. In contrast, a Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of TAK-1 (TGFβ-activated kinase-1) named MOM-1 has been shown to activate a NEMO-like kinase (NLK) named LIT-1, which phosphorylates TCF/LEF factors resulting in inhibition of the interaction of β-catenin/TCF complexes with DNA and suppression of wnt signaling [13••,14,15]. In addition, the C. elegans β-catenin homologue, Wrm-1, forms a complex with and activates LIT-1 [13••]. Thus this protein kinase is able to inhibit Wnt signaling both as part of a feedback loop and as a transducer of a signal from another protein kinase. As LIT-1 is closely related to the Drosophila tissue polarity gene NEMO, this signaling pathway appears likely to be conserved among many metazoan phyla.

Other signaling pathways are likely to modulate wnt signaling at many steps. In Dictyostelium, for example, a novel cAMP-activated tyrosine kinase ZAK1 has been shown to activate GSK-3βand thereby to control several developmental pathways [16••]. Similar kinases seem likely to be present in metazoan phyla. In Drosophilia, naked cuticle encodes a protein which is induced by Wnt signaling and functions to limit Wnt responsiveness [17•]. The protein encoded by this gene is homologous to members of the recoverin family, which have been shown to bind and regulate activity of protein kinases. This protein also contains a putative Ca2+-binding domain. Although its mechanism of action is not known, it may function as a Ca2+-controlled regulator of a protein kinase.

Some of the proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway have multiple functions. Dishevelled has been shown to control Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK) in addition to GSK-3β[18•,19•]. β-catenin also binds to the cytoplasmic domains of the classical cadherins and provides an essential linkage between cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion and the F-actin cytoskeleton. Association with cadherins effectively sequesters β-catenin from the cytoplasmic pool that is responsive to Wnt signaling [20•,21•,22]. Thus regulation of cadherin expression and function can modulate Wnt signaling through β-catenin. As both cad-herins and wnt proteins have been shown to regulate aspects of synapse formation, the interplay between these proteins may prove particularly interesting in the nervous system (e.g. [23,24••]).

Some of the most interesting work on wnt signaling during the past few years has examined pathways that are not dependent upon transcription (see Figure 1). The Wnt signaling pathway controls orientation of mitotic spindles in C. elegans by a pathway not requiring gene transcription [25,26]. Control by Wnt and Frizzled signaling of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye appears to be mediated through RhoA, a small G protein [27]. These observations could be explained by regulation of other proteins by GSK-3β. Known targets of this enzyme include microtubule-associated proteins [28]. In addition, recent work has also shown that some wnt proteins can activate phosphatidyl inositide metabolism, Ca2+ fluxes, and protein kinase C (PKC) by pathways dependent upon trimeric G proteins [29,30,31••]. The Wnt proteins able to activate phosphatidyl inositide metabolism and PKC appear to be distinct from those that activate β-catenin [32]. They also appear to activate a set of Frizzled receptors distinct from those controlling β-catenin activity. This more recent work has shown that Wnt signaling is much more divergent and, presumably, more flexible than was apparent from early work. In the future, it seems likely that additional signaling pathways will be discovered. Much work remains to understand mechanisms of specificity and of control of final targets, such as cell fate or morphology.

Regulation of Wnt protein expression and action

Given the complexity of the Wnt signal transduction pathway, it is not surprising that many extracellular molecules have been found to regulate Wnt action. Proteins that appear to act as Wnt protein antagonists include the secreted Frizzled related proteins (sFRP), Dickkopf (Dkk), and cerberus (Cer). sFRPs, as their name suggests, are secreted proteins with amino-acid similarity to the Frizzled receptors [3,32–35]. sFRPs are thought to act as Wnt antagonists by forming nonfunctional interactions with either Wnts or Frizzled receptors (for example see [36]).

Many of the sFRP genes have been found to be expressed in the developing nervous system, usually in close proximity to Wnt-positive tissues [37–40]. Dkk-1 belongs to a secreted family of proteins with two highly-conserved cysteine-rich domains; these proteins can induce head (brain) formation in Xenopus and are potent inhibitors of Wnt signaling, although the exact mechanism of inhibition is currently unknown [41]. Finally, Cer is another secreted protein with head-inducing activity in Xenopus. Cer can bind directly to Xwnt-8 and inhibit its activity in Xenopus axis duplication assays [42••]. Interestingly, Cer is a multivalent growth-factor antagonist, binding to Nodal, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), and Wnt proteins at different sites, suggesting cooperative regulation of signaling by these factors. Indeed, according to the two-inhibitor model for head induction, it is the combined inhibition of Wnts and BMPs that induce the presumptive forebrain (reviewed in [43]).

These three examples demonstrate that regulation of Wnt protein binding to its Frizzled receptors can be a crucial step in modulating Wnt signaling. The list of regulators of Wnt signaling is constantly growing, and many of these factors have not yet been investigated in the nervous system. For example, Wnt-inhibitory factor-1 (WIF-1) is a secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and can inhibit their activities during somitogenesis [44]. Extracellular regulation of Wnt protein is not only inhibitory; for example, the protein encoded by the division abnormally delayed (dally) gene is a cell-surface, heparan-sulphate-modified proteoglycan that potentiates signaling by Wnt and by decapentaplegic, a TGF-βhomologue [45•].

Little is known about the pathways in the developing nervous system that regulate Wnts at the level of gene transcription. Rowitch et al. [46] have isolated an evolutionarily conserved 110 base-pair cis-acting regulatory sequence from the mouse wnt-1 locus that is capable of recapitulating the wnt-1 expression pattern in the embryonic midbrain. Although this sequence contains consensus binding sites for transcription factors, the critical sites have not yet been identified. Wnt-2b, 3a, and 5a have been shown to mark the medial margin of the developing telencephalon just dorsal to the choroid plexus [47]. Extra-toesJ (XtJ) mouse mutants show a partial ventralization of telencephalon, with a loss of dorsal structures such as the choroid plexus and the neuroepithelial zone marked by the Wnt genes [48••]. XtJ carries a mutation in gli3, a vertebrate homolog of the Drosophila gene cubitus interruptus (ci), which encodes a Hedgehog-induced transcriptional regulator of the Drosophila wnt gene, wingless. The expression of sonic hedgehog in the ventral telencephalon is not affected in XtJ mice. Whether wnt transcription is directly activated by Gli3 or is indirectly induced upon correct dorsal specification is still an open question.

Wnt signaling in development of the nervous system

In recent work, Wnt signaling in Xenopus embryos has been shown to inhibit expression of BMP-4 and thereby activate neural development [49••]. BMP-4 expression had previously been shown to inhibit neural induction of the dorsal ectoderm. Antagonists of BMP-4 secreted by Spemann's organizer had been shown to control neural induction by inhibition of BMP-4 activity. This more recent work suggests that Wnt signaling contributes to neural induction by repressing BMP-4 expression, which makes the dorsal ectoderm more sensitive to these BMP antagonists. The TCF family of transcription factors appear to be involved because a dominant-negative TCF inhibits neural induction.

Wnt proteins have also been shown to regulate many of the early patterning events in the developing nervous system. As discussed earlier, inhibition of both BMP and Wnt signaling is essential for forebrain patterning [43]. At a slightly later stage, neural crest has been shown to be specified at the lateral edges of the neural plate prior to neural tube closure in Xenopus embryos. A Wnt-mediated signal from the posterior nonaxial mesoderm appears to establish a posterior-lateral domain in the lateral neural plate from which neural crest cells later emerge [50]. While inhibition of BMP signaling is essential to specify neural crest, an additional signal which can be inhibited by a dominant-negative Wnt-8 is required, implicating a Wnt signaling pathway [51]. Intriguingly the same dominant-negative Wnt-8, which prevents specification of the posterior-lateral domain in the neural plate and prevents specification of neural crest, was not effective in preventing neural induction in the work of Baker et al. [49••]. Thus there appear to be differences in the signaling pathways that mediate these actions.

Two Wnt proteins, Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a, are coexpressed at the dorsal midline of the developing neural tube and appear to have redundant functions in controlling dorsolateral patterning in murine embryos [52]. In the absence of these two proteins, many fewer neural crest derivatives and dorsal-lateral neural precursors within the neural tube are found. As cells expressing markers corresponding to different positions along the dorsal–ventral axis continue to be present, these authors suggest that Wnt-signaling is not controlling determination but promoting expansion of precursors of the neural crest and dorsal-lateral neural tube.

More direct evidence that Wnt proteins control the determination of neural crest has been obtained by injection of activators or inhibitors of the Wnt signaling pathway into single neural crest progenitors in Zebra fish [53]. In these experiments, activation of the Wnt pathway promoted pigment cell formation, while inhibition of Wnt signaling promoted formation of neurons and glia. These molecules appeared to be acting instructively because injection of activators resulted in formation of pigment cells at the expense of neurons and glia while injection of inhibitors had an opposite effect. In more recent work from the same laboratory, the Wnt pathway has been shown to regulate directly a transcription factor which is essential for pigment cell formation [54•]. Thus, these results suggest that Wnt proteins are not simply controlling expansion of precursor pools [55••].

Many of the molecules involved in the dorsal–ventral patterning of the neural tube also direct patterning of the telencephalon (for example see [56•]). In particular, the wnt 3a, 5a, and 2b genes are expressed in the cortical hem which forms the boundary between the hippocampus and choroid plexus in the embryonic cerebral cortex [47]. Recently it has been shown that absence of Wnt3a does not detectably perturb specification of cells adjacent to the hem but does result in a striking reduction in their proliferation [57••]. As a consequence, there is a failure of hippocampal development with the dentate gyrus completely absent and CA3, CA1, and the subiculum absent in rostral regions and severely reduced in caudal regions of the cortex. There is a similar failure of hippocampal development in a mouse expressing a gene encoding a Lef-1-lacZ fusion product which interferes with β-catenin activation of TCF/LEF proteins [58•]. In contrast, most of the hippocampus develops normally in a Lef-1 knockout but dentate granule cells are missing and BrdU labeling demonstrates that there is a large decrease in proliferation of their precursors [58•]. Glia and interneurons are still present in the dentate gyrus, so the deficit in proliferation appears to be limited to a subpopulation of the precursors that populate this region. Thus Wnt signaling through β-catenin and TCF/LEF transcription factors controls proliferation of all or almost all hippocampal cell precursors, but different TCF/LEF family members transmit this signal in different subpopulations.

Wnt proteins continue to be expressed in the brain at later embryonic and postnatal stages and a series of interesting papers implicate Wnt signaling in many aspects of cerebellar development. Within the postnatal cerebellum, expression of the gene encoding Wnt-3a is restricted to Purkinje cells and results suggest strongly that expression depends upon the presence of cerebellar granule cells [59]. Wnt-7a expression is restricted to granule cells [60]. Wnt-7a has autocrine or paracrine effects upon these cells, increasing levels of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein Synapsin I and controlling through GSK-3βphosphorylation of a microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP-1B) [28,60]. Granule cells have been shown to secrete factors that induce synaptic remodeling in the mossy fiber terminals that form elaborate synaptic contacts with these cells named mossy fiber rosettes. Recent work has shown that this effect can be mimicked by Wnt-7a in vitro [24••]. Wnt-7a mutant mice also show a delay in the morphological maturation of these rosettes and in accumulation of synapsin I. Effects in vivo are transient, but Wnt-7b has been shown to be also expressed within granule cells in vivo and to have effects similarly to Wnt-7a on mossy fibers in vitro. Thus, it is not unexpected that the cerebellar phenotype of the Wnt-7a mouse is transient. These results suggest that Wnt proteins may have widespread regulatory effects upon neuronal maturation, synapse formation and synaptic plasticity.

Inhibition of β-catenin or TCF rescues cells from apoptosis in the Drosophila eye [61]. This has stimulated work to examine the possible roles of the Wnt signaling pathway in regulation of neuronal apoptosis and degeneration. In contrast to the results in Drosophila, inhibition of β-catenin or TCF has been reported to render hippocampal neurons more sensitive to apoptosis [62]. Forced expression of the gene encoding β-catenin has been shown to result in elevated levels of p53 in some cells [63], which depending upon cell type could either promote or protect cells from apoptosis. Pursuing a possible involvement of these molecules in neurodegenerative disease, several groups have recently shown that β-catenin associates with presenilins, membrane proteins implicated in Notch signaling and in Alzheimer's disease [64]. GSK-3βand APC have also been detected in this complex, but there is disagreement about whether presenilins stabilize or destabilize β-catenin [62,65]. Intriguingly, tau has also been detected in this complex and GSK-3βis a strong candidate to generate the hyperphosphorylated Tau which is found in paired helical filaments in Alzheimer's disease. Many pieces are missing from this picture. In particular, it is not clear whether association with presenilin regulates the activity of GSK-3β. It is also uncertain whether the mutated products of presenilin which predispose persons to developing Alzheimer's disease alter the properties of this complex or of any molecules within it. While much remains to be explored, these data do suggest that deficits in Wnt signaling may promote formation of paired helical filaments and render neurons more sensitive to apoptosis in the mature brain.

Downstream targets Of Wnt signaling

Despite significant advances in the understanding of Wnt signal transduction, very few downstream targets of this pathway are currently known. Some of these targets include the mab-5 Hox gene in C. elegans [66], Sloppy Paired [67] and Ubx in Drosophila, siamois in Xenopus, and c-MYC in mammalian cells (reviewed in [6•]). All of these known downstream genes are transcriptional factors whose targets are not well characterized, and hence we are left with a large gap in our knowledge on how the transcription-dependent morphological effects of Wnt signaling are carried out during development. However, some hints as to how Wnts can effect neuronal patterning have recently emerged.

First, in a study concerning neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) regulation, we have found that epithelial-expressed Wnts can induce mesenchymal expression of NT-3 in the limb-bud during mouse development [68••]. Neurotrophins are a family of growth factors expressed in neuronal target tissues that regulate neuronal survival, differentiation, and function [69].

A link between Wnt signaling and neurotrophin expression raises the question if any of the known effects of Wnts, such as regulation of neuronal survival or differentiation, are mediated through neurotrophins. Although it is not yet known how direct the Wnt–neurotrophin connection is, LEF-1 is required for the development of many organs involved in epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, and many of these regions express NT-3.

Second, the Wnt pathway has been shown to regulate the expression of the substrate adhesion molecule Fibronectin [70••]. Using Xenopus fibroblasts, it has been shown that the fibronectin gene is a direct target of Wnt signaling and that LEF can bind and activate the fibronectin promoter. Furthermore, overexpression of cadherins in these fibroblasts downregulates fibronectin. As expression can be restored by coexpressing β-catenin, cadherins appear to be inhibiting fibronectin expression by sequestering β-catenin. This work suggests that free β-catenin, due to its dual roles in Wnt signaling and cadherin-mediated cell adhesion, functions as a switch between cell–cell versus cell–substrate adhesion and that this is one mechanism by which it has a profound effect on patterning and development [71].

Conclusions

Our understanding of Wnt signaling complexity has advanced tremendously in the last few years. The identification of the Frizzled proteins as Wnt receptors, and the alternative path of Wnt signaling through G-protein mediated calcium release are two of many new findings. In addition, Wnt signaling is now thought to share elements involved in disparate signal transduction pathways. These include interactions with CK I-ε, JNK, cAMP-dependent protein kinase, notch signaling, cadherin-mediated cell adhesion, TGF-βand BMP signaling. How these interactions are coordinated and executed are compelling challenges for the future. The discovery of a vast number of extracellular molecules that potentiate or inhibit the binding of Wnts to their receptors alerts us to the importance of having multiple steps to control Wnt actions. The links between regulatory molecules of the Wnt signal transduction pathway and its final targets and morphological effects on cells are not well understood. With the advent of DNA microarray technology we will soon have a more complete repertory of genes that are affected by Wnt signaling. Within the nervous system, the function of Wnts is still sketchy: roles in proliferation, specification, and differentiation have been demonstrated but, in most instances, mechanisms remain undefined. A deeper understanding of the role of the different components of the Wnt signaling pathway will emerge with the help of nervous-system-specific knockouts, which will help separate neuronal-specific phenotypes from roles of Wnts in other systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of their laboratory for many discussions on development, and Elizabeth Grove and Patricia Salinas for providing preprints of papers discussed in this review. Portions of the work from the authors' laboratory were supported by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (P01-16033, Louis Reichardt, PI) and a Silvio Conte Center grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Lily Yeh Jan, PI). Louis Reichardt is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- Cer

Cerberus

- Ci

cubitus interruptus

- CkI-ε

casein kinase I-ε

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- dally

division abnormally delayed

- Dkk

Dickkopf

- Dsh

Dishevelled

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- IP3

inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate

- JNK

Jun amino-terminal kinase

- LEF

lymphoid enhancer factor

- NEMO

NFκB essential modulator

- NFκB

nuclear factor κB

- NLK

NEMO-like kinase

- NT-3

neurotrophin-3

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- sFRP

secreted Frizzled related protein

- TAK-1

TGF-β-activated kinases-1

- TCF

T-cell factor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- WIF-1

Wnt inhibitory factor-1

- XtJ

Extra toesJ

Contributor Information

Ardem Patapoutian, Email: ardem@scripps.edu.

Louis F Reichardt, Email: lfr@cgl.ucsf.edu.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Brown JD, Moon RT. Wnt signaling: why is everything so negative? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:182–187. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2•.Wodarz A, Nusse R. Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:59–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59. This paper provides an excellent review of Wnts and their functions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nusse laboratory. Web pages: http://www.stanford.edu/∼rnusse/wntwindow.html.

- 4.Rattner A, Hsieh JC, Smallwood PM, Gilbert DJ. A family of secreted proteins contains homology to the cysteine-rich ligand-binding domain of frizzled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2859. The important discovery of Wnt receptor homologues that function as competitive antagonists of frizzled receptors is presented in this paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salinas PC. Wnt factors in axonal remodelling and synaptogenesis. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;65:101–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Nusse R. WNT targets. Repression and activation. Trends Genet. 1999;15:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01634-5. This is a brief, but lucid summary of current knowledge of wnt target genes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. Beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Hart M, Concordet JP, Lassot I, Albert I, del los Santos R. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr Biol. 1999;9:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80091-8. This paper from the Polakis laboratory – with similar papers of Latres and colleagues [9] and Winston and colleagues [10] – demonstrates that an F-box protein named β-TrCP, a homologue of Drosophila Slimb, interacts with phosphorylated β-catenin and mediates its ubiquitination. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latres E, Chiaur DS, Pagano M. The human F box protein beta-Trcp associates with the Cul1/Skp1 complex and regulates the stability of beta-catenin. Oncogene. 1999;18:849–854. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IκBα and α-catenin and stimulates IκBα ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13:270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Nishita M, Hashimoto MK, Ogata S, Laurent MN, Ueno N, Shibuya H, Cho KWY. Interaction between Wnt and TGF-β signalling pathways during formation of Spemann's organizer. Nature. 2000;403:781–785. doi: 10.1038/35001602. The authors demonstrate that LEF/TCF and β-catenin form a complex with Smad4 in vivo and regulate the expression of twin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Sakanaka C, Leong P, Xu L, Harrison SD, Williams LT. Casein kinase Iε in the wnt pathway: regulation of beta-catenin function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12548–12552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12548. Members of the Williams group identify casein kinase I ε as an activator of wnt signaling and show that a kinase-defective casein kinase I ε attenuates wnt signaling. Casein kinase I ε is detected in a complex with Dishevelled Axin and Glycogen synthase kinase 3β. These results establish this protein kinase as a regulator of the wnt signaling pathway upstream of β-catenin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13••.Rocheleau CE, Yasuda J, Shin TH, Lin R, Sawa H, Okano H, Priess JR, Davis RJ, Mello CC. WRM-1 activates the LIT-1 protein kinase to transduce anterior/posterior polarity signals in C. elegans. Cell. 197:999. 717–726. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80784-9. A pathway downstream of β-catenin that is independent of TCFs is described here. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishitani T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Nagai S, Nishita M, Meneghini M. The TAK1-NLK-MAPK-related pathway antagonizes signalling between beta-catenin and transcription factor TCF. Nature. 1999;399:798–802. doi: 10.1038/21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meneghini MD, Ishitani T, Carter JC, Hisamoto N, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Thorpe CJ, Hamill DR, Matsumoto K, Bowerman B. MAP kinase and Wnt pathways converge to downregulate an HMG-domain repressor in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;399:793–797. doi: 10.1038/21666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16••.Kim L, Liu J, Kimmel AR. The novel tyrosine kinase ZAK1 activates GSK3 to direct cell fate specification. Cell. 1999;99:399–408. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81526-3. An intriguing regulatory patterning in Dictyostelium is described that seems likely to be conserved in higher metazoan phyla. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Zeng W, Wharton KA, Jr, Mack JA, Want K, Gadbaw M, Suyama K, Klein PS, Scott MA. naked cuticle encodes an inducible antagonist of Wnt signalling. Nature. 2000;403:789–792. doi: 10.1038/35001615. This paper describes an interesting protein that functions to limit the extent of Wnt signaling in Drosophila Its structure suggests that it acts in the receiving cell to inhibit Wnt signaling but its locus of action is not known. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Boutros M, Paricio N, Strutt DI, Mlodzik M. Dishevelled activates JNK and discriminates between JNK pathways in planar polarity and wingless signaling. Cell. 94:1998. 109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81226-x. In this paper, dishevelled is shown to function in both wnt and JNK signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Li L, Yuan H, Xie W, Mao J, Caruso AM, McMahon A, Sussman DJ, Wu D. Dishevelled proteins lead to two signaling pathways. Regulation of LEF-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 274:1999. 129–134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.129. This important paper describes the bi-functional role of dishevelled in wnt and JNK signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Fagotto F, Funayama N, Gluck U, Gumbiner BM. Binding to cadherins antagonizes the signaling activity of beta-catenin during axis formation in Xenopus. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:1105–1114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1105. Gumbiner and colleagues demonstrate that cadherins sequester β-catenin and thereby inhibit wnt signaling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Simcha I, Shtutman M, Salomon D, Zhurinsky J, Sadot E, Geiger B, Ben-Ze'ev A. Differential nuclear translocation and transactivation potential of beta-catenin and plakoglobin. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1433–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1433. Gieger and colleagues demonstrate that β-catenin and its mammalian homo-logue plakoglobin differ in their abilities to interact with LEF-1 and with vinculin and to drive translocation of these proteins to the nucleus. β-catenin is also much more effective in activating LEF-1-dependent gene transcription than plakoglobin. Results in this paper also show that cytoplasmic binding partners of β-catenin favor its retention in the cytoplasm and therefore inhibit Lef-1/β-catenin-dependent gene transcription. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadot E, Simcha I, Shtutman M, Ben-Ze'ev A, Geiger B. Inhibition of beta-catenin-mediated transactivation by cadherin derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15339–15344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka H, Shan W, Phillips GR, Arndt K, Bozdagi O, Shapiro L, Huntley GW, Benson DL, Colman DR. Molecular modification of N-cadherin in response to synaptic activity. Neuron. 2000;25:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24••.Hall AC, Lucas FR, Salinas PC. Axonal remodelling and synaptic differentiation in the cerebellum is regulated by WNT-7a signalling. Cell. 2000;100:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80689-3. In this elegant study from the Salinas laboratory, Wnt-7a is shown to modulate development of the glomerular rosettes formed by mossy fibers in contact with cerebellar granule cells. WNT-7a is expressed by cerebellar granule cells at the time of their initial contact by mossy fibers. In explant cultures, mossy fiber axons change morphology when they contact granule cells, developing enlarged growth cones with concentrations of the vesicle-associated protein synapsin I. These changes are also seen in the presence of Wnt-7a or Li+. In mice lacking Wnt-7a, there is a delay in formation of these rosettes and in appearance of the presynaptic marker synapsin I within them. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlesinger A, Shelton CA, Maloof JN, Meneghini M, Bowerman B. Wnt pathway components orient a mitotic spindle in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo without requiring gene transcription in the responding cell. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2028–2038. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorpe CJ, Schlesinger A, Bowerman B. Wnt signalling in Caenorhabditis elegans: regulating repressors and polarizing the cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strutt DI, Weber U, Mlodzik M. The role of RhoA in tissue polarity and Frizzled signalling. Nature. 1997;387:292–295. doi: 10.1038/387292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas FR, Goold RG, Gordon-Weeks PR, Salinas PC. Inhibition of GSK-3beta leading to the loss of phosphorylated MAP-1B is an early event in axonal remodelling induced by WNT-7a or lithium. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1351–1361. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slusarski DC, Corces VG, Moon RT. Interaction of Wnt and a Frizzled homologue triggers G-protein-linked phosphatidylinositol signalling. Nature. 1997;390:410–413. doi: 10.1038/37138. In this paper, the Moon group provides decisive evidence for a Wnt signaling pathway independent of Disheveled, β-catenin and TCFs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slusarski DC, Yang-Snyder J, Busa WB, Moon RT. Modulation of embryonic intracellular Ca2+ signaling by Wnt-5a. Dev Biol. 1997;182:114–120. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Sheldahl LC, Park M, Malbon CC, Moon RT. Protein kinase C is differentially stimulated by Wnt and Frizzled homologs in a G-protein-dependent manner. Curr Biol. 9:1999. 695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80310-8. In this paper, the authors extend their earlier work on activation of Ca2+ and Ca2+ signaling by a subset of Wnt proteins. Using translocation of a GFP-tagged PKC as an assay, they show that expression of Wnt5a or of a subset of Frizzled receptors results in PKC translocation and activation. They observe that, among those tested, the wnt and frizzled proteins appear to activate either G-protein dependent pathways that activate PKC or β-catenin-dependent transcription of Siamois, but not both pathways. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finch PW, He X, Kelley MJ, Uren A, Schaudies RP, Popescu NC, Rudikoff S, Aaronson SA, Varmus HE, Rubin JS. Purification and molecular cloning of a secreted, Frizzled-related antagonist of Wnt action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6770–6775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leyns L, Bouwmeester T, Kim SH, Piccolo S, De Robertis EM. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell. 1997;88:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Krinks M, Lin K, Luyten FP, Moos M., Jr Frzb, a secreted protein expressed in the Spemann organizer, binds and inhibits Wnt-8. Cell. 1997;88:757–766. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81922-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ladher RK, Church VL, Allen S, Robson L, Abdelfattah A, Brown NA, Hattersley G, Rosen V, Luyten FP, Dale, L, Francis-West PH. Cloning and expression of the Wnt antagonists Sfrp-2 and Frzb during chick development. Dev Biol. 2000;218:183–198. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CS, Buttitta LA, May NR, Kispert A, Fan CM. SHH-N upregulates Sfrp2 to mediate its competitive interaction with WNT1 and WNT4 in the somitic mesoderm. Development. 2000;127:109–118. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayr T, Deutsch U, Kuhl M, Drexler HC, Lottspeich F, Deutzmann R, Wedlich D, Risau W. Fritz: a secreted frizzled-related protein that inhibits Wnt activity. Mech Dev. 1997;63:109–125. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoang BH, Thomas JT, Abdul-Karim FW, Correia KM, Conlon RA, Luyten FP, Ballock RT. Expression pattern of two Frizzled-related genes, Frzb-1 and Sfrp-1, during mouse embryogenesis suggests a role for modulating action of Wnt family members. Dev Dyn. 1998;212:364–372. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199807)212:3<364::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leimeister C, Bach A, Gessler M. Developmental expression patterns of mouse sFRP genes encoding members of the secreted frizzled related protein family. Mech Dev. 1998;75:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lescher B, Haenig B, Kispert A. sFRP-2 is a target of the Wnt-4 signaling pathway in the developing metanephric kidney. Dev Dyn. 1998;213:440–451. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199812)213:4<440::AID-AJA9>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, Monaghan AP, Blumenstock C, Niehrs C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature. 1998;391:357–362. doi: 10.1038/34848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42••.Piccolo S, Agius E, Leyns L, Bhattacharyya S, Grunz H, Bouwmeester T, De Robertis EM. The head inducer Cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of Nodal, BMP and Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;397:707–710. doi: 10.1038/17820. De Robertis and his colleagues describe the pleiotrophic properties of the head inducer Cerberus in controlling signaling through many growth and differentiation factor-mediated pathways. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niehrs C. Head in the WNT: the molecular nature of Spemann's head organizer. Trends Genet. 1999;15:314–319. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh JC, Kodjabachian L, Rebbert ML, Rattner A, Smallwood PM, Samos CH, Nusse R, Dawid IB, Nathans J. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 1999;398:431–436. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45•.Tsuda M, Kamimura K, Nakato H, Archer M, Staatz W, Fox B, Humphrey M, Olson S, Futch T, Kaluza V, et al. The cell-surface proteoglycan Dally regulates Wingless signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 1999;400:276–280. doi: 10.1038/22336. This paper describes an intriguing role for proteoglycans in wnt signaling similar to roles of proteoglycans in FGF and TGF signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowitch DH, Echelard Y, Danielian PS, Gellner K, Brenner S, McMahon AP. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved 110 base-pair cis-acting regulatory sequence that governs Wnt-1 expression in the murine neural plate. Development. 1998;125:2735–2746. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.14.2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grove EA, Tole S, Limon J, Yip L, Ragsdale CW. The hem of the embryonic cerebral cortex is defined by the expression of multiple Wnt genes and is compromised in Gli3-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125:2315–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Tole S, Ragsdale CW, Grove EA. Dorsoventral patterning of the telencephalon is disrupted in the mouse mutant extra-toes(J) Dev Biol. 217:2000. 254–265. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9509. The authors follow up on their initial observation that Wnt expression is compromised in Gli3 mutant mice (extra-toes) Here, the authors show that this disruption is caused by a partial ventralization of the dorsal telencephalon The loss of Bmp and Wnt gene expression in the cortical hem is postulated to be the cause for this ventralization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49••.Baker JC, Beddington RS, Harland RM. Wnt signaling in Xenopus embryos inhibits bmp4 expression and activates neural development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3149–3159. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3149. This elegant paper from the Harland lab describes a novel mechanism by which wnt proteins affect early embryonic patterning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bang AG, Papalopulu N, Goulding MD, Kintner C. Expression of Pax-3 in the lateral neural plate is dependent on a Wnt-mediated signal from posterior nonaxial mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1999;212:366–380. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaBonne C, Bronner-Fraser M. Neural crest induction in Xenopus: evidence for a two-signal model. Development. 1998;125:2403–2414. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ikeya M, Lee SM, Johnson JE, McMahon AP, Takada S. Wnt signalling required for expansion of neural crest and CNS progenitors. Nature. 1997;389:966–970. doi: 10.1038/40146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorsky RI, Moon RT, Raible DW. Control of neural crest cell fate by the Wnt signalling pathway. Nature. 1998;396:370–373. doi: 10.1038/24620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Dorsky RI, Raible DW, Moon RT. Direct regulation of nacre, a zebrafish MITF homolog required for pigment cell formation, by the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 14:2000. 158–162. This paper presents evidence arguing that wnt signaling controls differentiation, not simply proliferation of neural crest cells. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55••.Lee KJ, Jessell TM. The specification of dorsal cell fates in the vertebrate central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 22:1999. 261–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.261. This review article is recommended as a lucid discussion of the role of wnt proteins and other patterning molecules in directing patterning of the vertebrate central nervous system. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56•.Grove EA, Tole S. Patterning events and specification signals in the developing hippocampus. Cerebral Cortex. 1999;9:561. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.551. This is an excellent review of current knowledge about development of the hippocampus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57••.Lee SM, Tole S, Grove E, McMahon AP. A local Wnt-3a signal is required for development of the mammalian hippocampus. Development. 2000;127:457–467. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.457. This paper from the Grove and McMahon laboratories describes elegantly the role of wnt in development of the hippocampus and adjacent regions in the CNS. It includes very strong evidence that wnt-3a is controlling proliferation of hippocampal precursors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Galceran J, Miyashita-Lin EM, Devaney E, Rubenstein JL, Grosschedl R. Hippocampus development and generation of dentate gyrus granule cells is regulated by LEF1. Development. 2000;127:469–482. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.469. In this paper, Grosschedl and colleagues show that TCF factors play an essential role in development of the entire hippocampus while LEF-1 alone is only essential for formation of dentate granule cells. Together with the work of the Grove lab, the paper indicates that wnt proteins are important for development of the entire hippocampus but different TCFs or combinations of TCFs are important in hippocampal subfields. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salinas PC, Fletcher C, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nusse R. Maintenance of Wnt-3 expression in Purkinje cells of the mouse cerebellum depends on interactions with granule cells. Development. 1994;120:1277–1286. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lucas FR, Salinas PC. WNT-7a induces axonal remodeling and increases synapsin I levels in cerebellar neurons. Dev Biol. 1997;192:31–44. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmed Y, Hayashi S, Levine A, Wieschaus E. Regulation of armadillo by a Drosophila APC inhibits neuronal apoptosis during retinal development. Cell. 1998;93:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Z, Hartmann H, Do VM, Abramowski D, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Sommer B, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Saftig P, et al. Destabilization of beta-catenin by mutations in presenilin-1 potentiates neuronal apoptosis. Nature. 1998;395:698–702. doi: 10.1038/27208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Damalas A, Ben-Ze'ev A, Simcha I, Shtutman M, Leal JF, Zhurinsky J, Geiger B, Oren M. Excess beta-catenin promotes accumulation of transcriptionally active p53. EMBO J. 1999;18:3054–3063. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderton BH. Alzheimer's disease: clues from flies and worms. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R106–R109. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murayama M, Tanaka S, Palacino J, Murayama O, Honda T, Sun XY, Yasutake K, Hihonmatsu N, Wolizin B, Takashima A. Direct association of presenilin-1 with β-catenin. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:73–77. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maloof JN, Whangbo J, Harris JM, Jongeward GD, Kenyon C. A Wnt signaling pathway controls hox gene expression and neuroblast migration in C. elegans. Development. 1999;126:37–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhat KM, van Beers EH, Bhat P. Sloppy paired acts as the downstream target of Wingless in the Drosophila CNS and interaction between sloppy paired and gooseberry inhibits sloppy paired during neurogenesis. Development. 2000;127:655–665. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68••.Patapoutian A, Backus C, Kispert A, Reichardt LF. Regulation of neurotrophin-3 expression by epithelial-mesenchymal interactions: the role of Wnt factors. Science. 1999;283:1180–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1180. Neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) is dynamically expressed, resembling a moving target for early dorsal root ganglion axons. However, neurons are not required for NT-3 expression in limb-buds; instead epithelial Wnt factors induce its expression in the adjacent mesenchyme. Therefore, Wnt factors control NT-3 expression and thus may regulate axonal growth and guidance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reichardt LF, Farinas I. Neurotrophic factors and their receptors: roles in neurolan development and function. In: Cowan MW, Jessell TM, Zipurski L, editors. Molecular Approaches to Neural Development. Oxford University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 220–263. [Google Scholar]

- 70••.Gradl D, Kühl M, Wedlich D. The Wnt/Wg signal transducer beta-catenin controls fibronectin expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5576–5587. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5576. In this paper, the promoter of Xenopus fibronectin is thoroughly analyzed, LEFTCF binding sites are identified and characterized. The work suggests that Wnts can regulate important cellular functions by directly upregulating expression of extracellular matrix proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sehgal RN, Gumbiner BM, Reichardt LF. Antagonism of cell adhesion by an alpha-catenin mutant, and of the Wnt-signaling pathway by alpha-catenin in Xenopus embryos. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1033–1046. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moon laboratory. Web pages: http://faculty.washington.edu/rtmoon.