Abstract

Background

The determination of appropriate duration of in‐the‐field cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients is one of the biggest challenges for emergency medical service providers and clinicians. The appropriate CPR duration before termination of resuscitation remains unclear and may differ based on initial rhythm. We aimed to determine the relationship between CPR duration and post‐OHCA outcomes.

Methods and Results

We analyzed the records of 17 238 OHCA patients (age ≥18 years) who achieved prehospital return of spontaneous circulation. Data were prospectively recorded in a nationwide, Japanese database between 2011 and 2012. The time from CPR initiation to prehospital return of spontaneous circulation (CPR duration) was calculated. The primary end point was 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes (Cerebral Performance Category [CPC] scale; CPC 1–2). The 1‐month CPC 1–2 rate was 21.8% (n=3771). CPR duration was inversely associated with 1‐month CPC 1–2 (adjusted unit odds ratio: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.94–0.95). Among all patients, a cumulative proportion of >99% of 1‐month CPC 1–2 was achieved with a CPR duration of 35 minutes. When sorted by the initial rhythm, the CPR duration producing more than 99% of survivors with CPC 1–2 was 35 minutes for shockable rhythms and pulseless electrical activity, and 42 minutes for asystole.

Conclusions

CPR duration was independently and inversely associated with favorable 1‐month neurological outcomes. The critical prehospital CPR duration for OHCA was 35 minutes in patients with initial shockable rhythms and pulseless electrical activity, and 42 minutes in those with initial asystole.

Keywords: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, epidemiology, heart arrest, resuscitation

Subject Categories: Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiac Care, Epidemiology

Introduction

In recent years, the survival rate from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in industrialized countries has increased because of major advances in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1, 2, 3, 4 However, the mortality rate remains high, and the survival to hospital discharge rate among OHCA patients is between 7.2% and 11%.1, 2, 3, 4 Studies have shown that the survival rate declines rapidly when the duration of CPR surpasses 10 minutes and even more rapidly if it exceeds 30 minutes.5, 6 In some studies,7, 8, 9 refractory cardiac arrest is thought to be present if, in the absence of preexisting hypothermia, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is not achieved despite more than 30 minutes of appropriate CPR. Clinical decision rules for the termination of resuscitation in the field have been developed to better utilize hospital healthcare resources, reduce the hazards to emergency medical service (EMS) providers, and increase the availability of care and transport for other patients.10, 11 Accordingly, in many EMS systems, patients with OHCA are declared dead at the scene after a predetermined CPR time interval is exceeded (often 30 minutes).12 However, the 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care and the 2015 AHA Guidelines Update for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care did not specify the appropriate duration of CPR to be conducted before out‐of‐hospital resuscitation efforts could cease.10, 13 Moreover, initial shockable rhythm has been shown to be a crucial prehospital variable for predicting favorable neurological outcomes after OHCA.14, 15 Therefore, we hypothesized that the appropriate duration of CPR before terminating resuscitation efforts is ≈30 minutes. In addition, we hypothesized that the appropriate duration of CPR is different according to the initial rhythm.

The objectives of this study were (1) to determine the relationship between duration of prehospital CPR conducted by EMS providers and survival with favorable neurological outcomes after OHCA, and (2) to determine, according to the initial rhythm in OHCA, the critical prehospital CPR duration that would achieve prehospital ROSC and produce a cumulative proportion >99% of survivors and survivors with favorable neurological outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This investigation was a nationwide, population‐based, observational study of all adult patients (age ≥18 years) for whom resuscitation had been performed after OHCA in Japan between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2012. Cessation of cardiac mechanical activities, confirmed by the absence of signs of circulation, indicated cardiac arrest.16 The etiology of an arrest was presumed to be cardiac unless evidence suggested an external etiology (trauma, hanging, drowning, drug overdose, or asphyxia), respiratory disease, cerebrovascular disease, malignant tumors, or any other noncardiac etiology. Physicians in charge and EMS personnel determined whether the arrest was of noncardiac or cardiac origin. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Kanazawa University. The requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Study Setting

Japan has nearly 127 million residents in an area of 378 000 km2, approximately two thirds of which is uninhabited, mountainous terrain.14, 15 The Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA) of Japan supervises the nationwide EMS system, while the local fire stations operate the local EMS systems. During the study period, all EMS providers performed CPR according to the 2010 Japanese CPR guidelines.17 Emergency lifesaving technicians, who are EMS providers, are allowed to use several resuscitation methods, including automated external defibrillators, insertion of an airway adjunct, insertion of a peripheral intravenous line, and administration of Ringer's Lactate solution.14, 15 However, only specially trained emergency lifesaving technicians receiving online physician instruction are permitted to insert a tracheal tube and administer intravenous epinephrine in the field.14, 15 On the other hand, as EMS personnel in Japan are legally prohibited from terminating resuscitation in the field (except in specific situations such as decapitation, incineration, decomposition, rigor mortis, or dependent cyanosis), most patients with OHCA undergo CPR by EMS providers and are subsequently transported to the hospital. The appropriate duration of on‐scene CPR by EMS personnel before transport to a hospital has not been predetermined.

Data Collection and Quality Control

In 2005, the FDMA launched an ongoing, prospective, population‐based, observational study involving all patients with OHCA who received EMS in Japan.18 EMS personnel at each center, in cooperation with the physician in charge, recorded data for patients with OHCA using an Utstein‐style template.16 The data were transferred to local, individual fire stations and subsequently integrated into the registry system on the FDMA database server. The data were checked for consistency by the computer system and confirmed by the FDMA. If the data form was incomplete, the FDMA returned it to the respective fire station and the form was completed. All data were transferred and stored in the nationwide database developed by the FDMA for public use. We analyzed this database with permission from the FDMA, which provided all the anonymous data to our research group.

The main variables included in the dataset were as follows: sex, age, etiology of arrest (dichotomously coded as presumed cardiac origin or not), initial identified cardiac rhythm, bystander witness status, bystander‐witnessed category (ie, whether the bystander was a family member, a layperson other than family, or EMS personnel), presence and maneuvers of bystander CPR, time of collapse recognition, time of emergency call, time of vehicle arrival at the scene, time of CPR initiation, time of prehospital ROSC, 1‐month survival, and neurological outcomes 1 month after cardiac arrest. Neurological outcomes were defined using the Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) scale (category 1: good cerebral performance, category 2: moderate cerebral disability, category 3: severe cerebral disability, category 4: coma or vegetative state, and category 5: death).16 The CPC categorization was determined by the in‐hospital physician in charge. Call‐to‐response time was calculated as the time from the emergency call to the time of vehicle arrival at the scene. CPR duration was defined as the time from initiation of CPR by EMS providers to prehospital ROSC.

Study End Points

The primary study end point was a favorable neurological outcome defined as a CPC of 1 or 2 (CPC 1–2) at 1 month. The secondary end point was a 1‐month survival time after OHCA.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the association between CPR duration and outcomes 1 month after OHCA by the initial recorded rhythm, we divided participants into 3 cohorts: ventricular fibrillation (VF)/pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), pulseless electrical activity (PEA), and asystole. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Lilliefors tests were performed to evaluate the distribution of continuous variables. Since some continuous variables were not normally distributed (all P<0.01), we used the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Dunn post‐hoc test to analyze the continuous variables. Chi‐square tests were performed for categorical variables to compare the characteristics and outcomes between groups. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was applied to compare the outcomes 1 month after OHCA according to initial cardiac rhythm. Furthermore, we performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to clarify the relationship between CPR duration and outcomes. Multivariate logistic regression analyses, including 12 prehospital variables, were performed to evaluate the association between CPR duration and 1‐month outcomes for all eligible patients. The potential prehospital confounders for the analytic model were selected based on biological plausibility and data from previous studies. The 12 selected variables included year, age, sex, bystander‐witnessed arrest (yes or no), bystander CPR (yes or no), presumed cardiac cause (yes or no), initial cardiac rhythm (VF/pulseless VT, PEA, or asystole), automated external defibrillator administration (yes or no), use of advanced airway management (yes or no), epinephrine administration (yes or no), call‐to‐response time, and CPR duration. We analyzed adjusted, multivariate logistic regression models using CPR duration as both a categorical and continuous variable. For analysis as a categorical variable, CPR duration was classified into 8 categories: 0 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 15, 16 to 20, 21 to 25, 26 to 30, 31 to 35, and >35 minutes.

We calculated the dynamic probability of 1‐month outcomes after OHCA as a function of CPR duration among all eligible participants. The dynamic probability of 1‐month outcomes was calculated using the following formula:

or:

where Nx was the number of patients who had undergone CPR for 0 minutes to x minutes and survived, or had survived with a CPC of 1–2 1 month after OHCA. That is, the dynamic probability of either 1‐month survival or CPC 1–2 indicated the proportion of the remaining 1‐month survivors or the survivors with a CPC of 1–2 after CPR lasting x minutes, to all patients with OHCA.

Moreover, we constructed cumulative proportion curves for 1‐month post OHCA outcomes over CPR time stratified by initial cardiac rhythm. The cumulative probability of 1‐month survival, or of a 1‐month CPC of 1–2, was calculated, for all patients and for each initial rhythm, using the following formula:

or:

where Nx was the number of patients for all or each initial rhythm who had undergone CPR for 0 minutes to x minutes and survived, or had survived with a CPC of 1–2 1 month after OHCA.

Then, using a 95% CI, we determined the critical prehospital EMS‐conducted CPR duration that would achieve a cumulative proportion >99% of those with 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes by initial rhythm.

Continuous variables were expressed as medians and 25th to 75th percentiles, whereas categorical variables were expressed as percentages. As an estimate of effect size and variability, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were reported. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP statistical package, version 11 Pro (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). All reported tests were 2‐tailed, and statistical significance was established as P<0.05.

Results

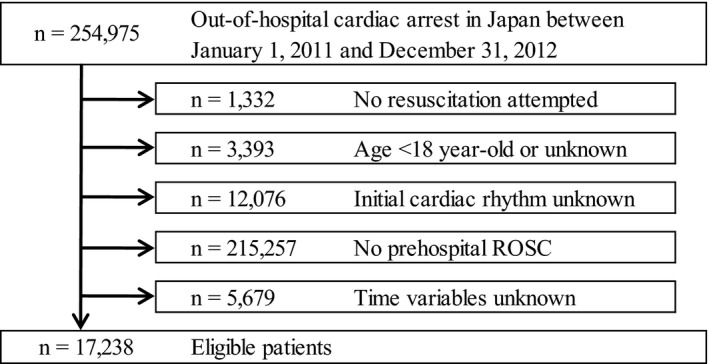

During the 2‐year study period, the details of 254 975 patients were documented in the database. Figure 1 shows the exclusion criteria for subjects in the present study. Patients who were treated by EMS personnel and achieved prehospital ROSC (n=17 238, 6.7%) were eligible for enrollment in this study. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study patients. Subjects in the VF/pulseless VT cohort were significantly younger than those in the other cohorts (P<0.0001). The proportion of males, witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, and cardiac cause in the VF/pulseless VT cohort was significantly higher than in the PEA and asystole cohorts (P<0.0001). The rate of advanced airway management use and epinephrine administration in the VF/pulseless VT cohort was significantly lower than in the PEA and asystole cohorts (P<0.0001). CPR duration in the VF/pulseless VT cohort was significantly shorter than in the other 2 cohorts (P<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Study exclusion flowchart. ROSC indicates return of spontaneous circulation.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants According to Initial Rhythm

| Characteristic | All Patients | Initial Cardiac Rhythm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VF/Pulseless VT | PEA | Asystole | ||

| n=17 238 (100%) | n=4864 (28.2%) | n=7422 (43.1%) | n=4952 (28.7%) | |

| Year | ||||

| 2011 | 8413 (48.8) | 2379 (48.9) | 3679 (49.6) | 2355 (47.6) |

| 2012 | 8825 (51.2) | 2485 (51.1) | 3743 (50.4) | 2597 (52.4) |

| Age, y, median (25–75%) | 74 (63–83) | 65 (56–75) | 77 (66–85) | 78 (67–85) |

| Male | 10 766 (62.4) | 3746 (77.0) | 4218 (56.8) | 2802 (56.6) |

| Witnessed arrest | 12 581 (72.9) | 4013 (82.5) | 5460 (73.6) | 3108 (62.8) |

| Bystander CPR | 7756 (45.0) | 2463 (50.6) | 2977 (40.1) | 2316 (46.8) |

| Cardiac cause | 9796 (56.8) | 4464 (91.8) | 3152 (42.5) | 2180 (44.0) |

| Prehospital AED administration | 5683 (33.0) | 4703 (96.7) | 570 (7.7) | 410 (8.3) |

| Use of advanced airway management | 7465 (43.3) | 1404 (28.9) | 3193 (43.0) | 2868 (57.9) |

| Epinephrine administration | 6655 (38.6) | 999 (20.5) | 2817 (37.9) | 2839 (57.3) |

| Call‐to‐response time, min, median (25–75%) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (5–8) | 7 (5–8) | 7 (5–9) |

| CPR duration, min, median (25–75%) | 14 (8–21) | 10 (6–16) | 14 (8–21) | 19 (13–25) |

Values are reported as n (%) unless indicated otherwise. CPR duration was defined as the time from initiation of CPR by emergency medical services personnel to prehospital return of spontaneous circulation. AED indicates automated external defibrillator; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

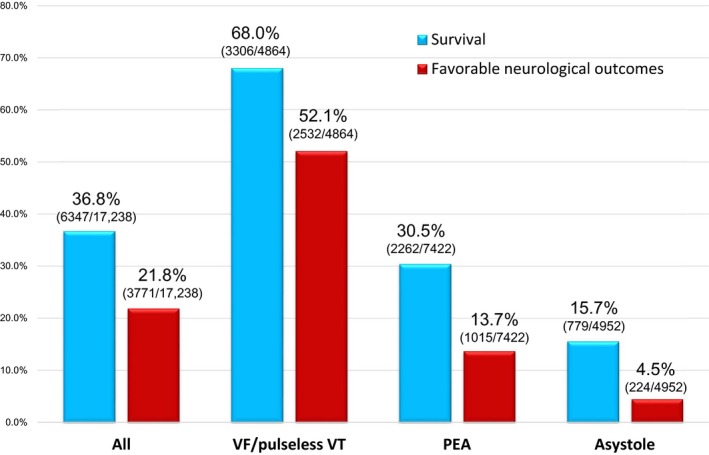

Figure 2 shows the 1‐month outcomes by initial rhythm. The rates of overall 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes were 36.8% and 21.8%, respectively. The rates of 1‐month survival (68.0%) and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes (52.1%) in the VF/pulseless VT cohort were significantly higher than in the PEA (30.5% and 13.7%, respectively) and asystole (15.7% and 4.5%, respectively) cohorts (all P for trend <0.0001). Table 2 shows the ORs of CPR duration (as both a categorical and continuous variable) for outcomes in the univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. CPR duration ≤30 minutes was independently associated with improved 1‐month survival. CPR duration ≤20 minutes was also independently associated with improved 1‐month favorable neurological outcomes. In the multivariate logistic regression models, initial VF/pulseless VT and PEA were independently associated with improved 1‐month survival (adjusted OR: 4.06, 95% CI: 3.43–4.80; adjusted OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.46–1.78, respectively) and 1‐month favorable neurological outcomes (adjusted OR: 5.16, 95% CI: 4.13–6.45; adjusted OR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.72–2.37, respectively) when compared to initial asystole. Furthermore, CPR duration was significantly and inversely associated with 1‐month favorable neurological outcomes for every 1‐minute increase in CPR time (adjusted unit OR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.95–0.96 for survival; adjusted unit OR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.94–0.95 for favorable neurological outcomes).

Figure 2.

One‐month outcomes after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest by the initial rhythm. PEA indicates pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Duration of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and 1‐Month Outcomes in Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Models

| Variables | 1‐Month Survival | 1‐Month Survival With Favorable Neurological Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| CPR duration (categorical variable), n=17 238 (100%) | ||||

| 0 to 5 min, n=2312 (13.4%) | 10.39 (7.90–13.89) | 5.09 (3.79–6.95) | 11.25 (7.92–16.56) | 4.18 (2.81–6.40) |

| 6 to 10 min, n=3618 (20.9%) | 9.44 (7.21–12.57) | 4.22 (3.16–5.74) | 9.69 (6.84–14.21) | 3.18 (2.15–4.84) |

| 11 to 15 min, n=3513 (20.3%) | 4.83 (3.69–6.43) | 3.32 (2.49–4.51) | 3.52 (2.48–5.19) | 1.82 (1.22–2.78) |

| 16 to 20 min, n=3043 (17.7%) | 2.85 (2.17–3.81) | 2.67 (1.99–3.63) | 2.03 (1.42–3.01) | 1.63 (1.09–2.51) |

| 21 to 25 min, n=2284 (13.2%) | 1.85 (1.40–2.49) | 1.97 (1.46–2.71) | 1.27 (0.87–1.90) | 1.32 (0.89–2.07) |

| 26 to 30 min, n=1287 (7.5%) | 1.32 (0.97–1.81) | 1.41 (1.02–1.97) | 0.90 (0.59–1.40) | 0.92 (0.58–1.49) |

| 31 to 35 min, n=669 (3.8%) | 1.1 (0.77–1.57) | 1.12 (0.77–1.64) | 1.08 (0.68–1.74) | 1.11 (0.66–1.88) |

| >35 min, n=512 (3.0%) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| CPR duration (continuous variable), mina | 0.92 (0.91–0.92) | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) | 0.90 (0.89–0.90) | 0.95 (0.94–0.95) |

CI indicates confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OR, odds ratio.

Odds ratios are expressed for 1‐minute increments. CPR duration was defined as the time from initiation of CPR by emergency medical services personnel to prehospital return of spontaneous circulation.

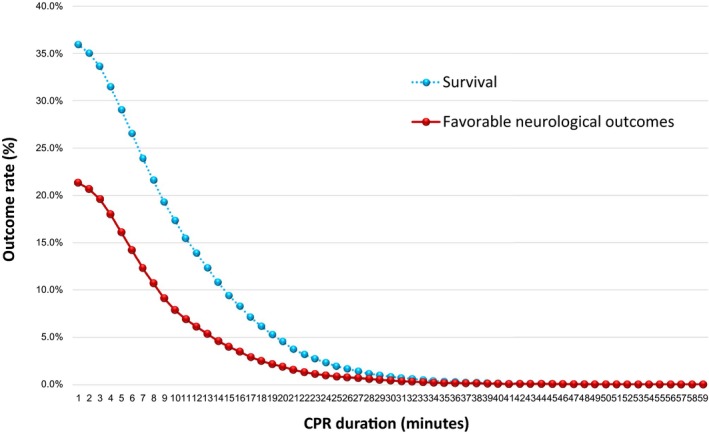

Figure 3 shows the dynamic probability of 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes by CPR duration. After 20 minutes of CPR, the probability of favorable 1‐month outcomes decreased from 36.8% (95% CI: 36.1–35.5%) to 4.6% (95% CI: 4.3–4.9%), for survival, and from 21.8% (95% CI: 21.3–22.5%) to 1.9% (95% CI 1.7–2.1%) for survival with favorable neurological outcomes. Furthermore, after 30 minutes of CPR, the rate of favorable outcomes decreased to 0.8% (95% CI: 0.7–1.0%) for survival and to 0.4% (95% CI: 0.3–0.5%) for survival with favorable neurological outcomes. None of the patients who received CPR for more than 53 minutes survived.

Figure 3.

Dynamic probability of 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes by CPR duration. CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

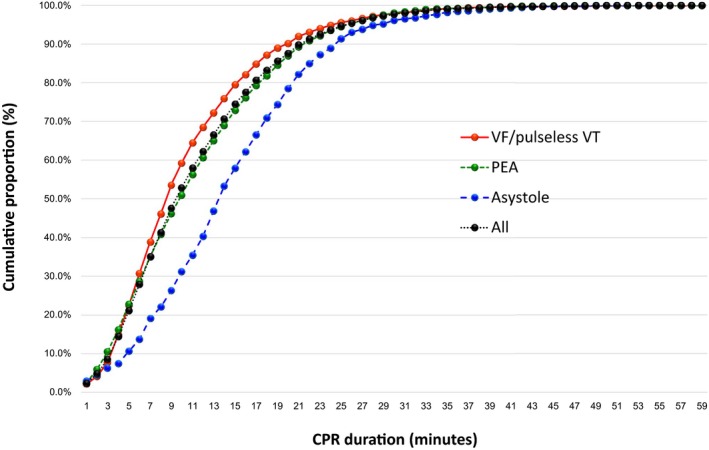

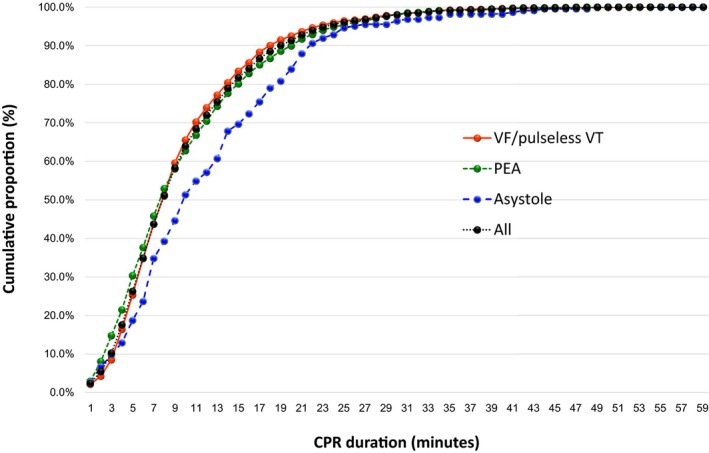

The cumulative proportions of 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes over CPR duration stratified by initial rhythm are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively. Table 3 shows the relationship between CPR duration in 5‐minute increments and 1‐month outcomes by initial rhythm. The cumulative proportion for 1‐month favorable neurological outcomes reached ≈80% after 15 minutes of CPR in both the VF/pulseless VT and PEA cohorts and ≈90% after 20 minutes of CPR in both groups (Table 3). However, in the asystole cohort, the cumulative proportion only reached ≈70% by the end of 15 minutes and 80% by the end of 20 minutes of CPR. For 1‐month survival, a cumulative proportion >99% was reached after 35 minutes of CPR (95% CI: 34–38 minutes) among the total sample, 35 minutes (95% CI: 34–39 minutes) among VF/pulseless VT patients, 34 minutes (95% CI: 33–39 minutes) among PEA patients, and 39 minutes (95% CI: 36–46 minutes) among asystole patients (Figure 4). Moreover, for 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes, a cumulative proportion >99% was reached after CPR durations of 35 minutes (95% CI: 34–39 minutes) for all patients, 35 minutes (95% CI: 34–40 minutes) for the VF/pulseless VT cohort, 35 minutes (95% CI 31–41 minutes) for the PEA cohort, and 42 minutes (95% CI: 31–49 minutes) for the asystole cohort (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Cumulative proportion of 1‐month survival by CPR duration according to the initial rhythm. CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 5.

Cumulative proportion of 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes by CPR duration stratified by the initial rhythm. CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 3.

Relationship Between the Duration of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and the Cumulative Proportion of 1‐Month Outcomes by Initial Rhythm

| CPR Duration (Minutes) | All Patients, n=17 238 | VF/Pulseless VT, n=4864 | PEA, n=7422 | Asystole, n=4952 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‐Month Survival, n=6347 | 1‐Month Favorable Neurological Outcomes, n=3771 | 1‐Month Survival, n=3306 | 1‐Month Favorable Neurological Outcomes, n=2532 | 1‐Month Survival, n=2262 | 1‐Month Favorable Neurological Outcomes, n=1015 | 1‐Month Survival, n=779 | 1‐Month Favorable Neurological Outcomes, n=224 | |

| 1 | 149 (2.3) | 91 (2.4) | 71 (2.1) | 55 (2.2) | 55 (2.4) | 30 (3.0) | 23 (3.0) | 6 (2.7) |

| 5 | 1340 (21.1) | 991 (26.3) | 742 (22.4) | 641 (25.3) | 515 (22.8) | 308 (30.3) | 83 (10.7) | 15 (18.8) |

| 10 | 3352 (52.8) | 2411 (63.9) | 1957 (59.2) | 1659 (65.5) | 1152 (50.9) | 637 (62.8) | 243 (31.2) | 115 (51.3) |

| 15 | 4724 (74.4) | 3080 (81.7) | 2626 (79.4) | 2111 (83.4) | 1647 (72.8) | 813 (80.1) | 451 (57.9) | 156 (69.6) |

| 20 | 5560 (87.6) | 3443 (91.3) | 2981 (90.2) | 2342 (92.5) | 1968 (87.0) | 913 (90.0) | 611 (78.4) | 188 (83.9) |

| 25 | 6010 (95.6) | 3621 (96.0) | 3160 (95.6) | 2442 (96.4) | 2138 (94.5) | 967 (95.3) | 712 (91.4) | 212 (94.6) |

| 30 | 6202 (97.7) | 3694 (98.0) | 3235 (97.9) | 2483 (98.1) | 2218 (98.1) | 995 (98.0) | 749 (96.1) | 216 (96.4) |

| 35 | 6287 (99.1) | 3739 (99.1) | 3278 (99.2) | 2513 (99.3) | 2244 (99.2) | 1006 (99.1) | 765 (98.2) | 220 (98.2) |

| 40 | 6319 (99.6) | 3753 (99.5) | 3294 (99.6) | 2523 (99.6) | 2252 (99.6) | 1010 (99.5) | 773 (99.2) | 220 (98.2) |

| 45 | 6335 (99.8) | 3763 (99.8) | 3298 (99.8) | 2526 (99.7) | 2260 (99.9) | 1014 (99.9) | 777 (99.7) | 223 (99.5) |

| 50 | 6346 (99.9) | 3770 (99.9) | 3305 (99.9) | 2531 (99.9) | 2262 (100.0) | 1015 (100.0) | 779 (100.0) | 224 (100.0) |

| 55 | 6347 (100.0) | 3771 (100.0) | 3306 (100.0) | 2532 (100.0) | 2262 (100.0) | 1015 (100.0) | 779 (100.0) | 224 (100.0) |

Values are reported as cumulative number of patients (%). CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA; pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Discussion

This 2‐year, prospective, observational study using data from a Japanese OHCA registry revealed that CPR duration was independently and inversely associated with 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes after adjusting for prehospital covariates. The study also found that, among the total sample, the critical duration of CPR to achieve a cumulative proportion >99% of survivors for both outcomes was 35 minutes. However, the critical CPR duration to achieve this proportion of survivors (>99%) differed based on initial rhythm.

Several studies examining the effect of CPR duration on clinical outcomes after cardiac arrest have been published.6, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 However, most of those studies focused on in‐hospital cardiac arrest,6, 19, 20, 21 while few studies have investigated data for patients with OHCA.22, 23 Using data from a single‐center registry (Pittsburgh, PA) and a modified Rankin scale (0–3), Reynolds et al22 determined that the probability of survival to hospital discharge rapidly declined with each minute of CPR. Similarly, Arima et al23 showed that in Funabashi, Japan, the prognosis of 172 OHCA VF patients deteriorated as prehospital CPR duration increased. These results were consistent with those of our present study that analyzed more than 17 000 OHCA patients using a nationwide registry in Japan.

Although the relationship between medical futility and ethical responsibility remains controversial, an objective criterion for medical futility (a <1% chance of survival) has been defined for interventions and drug therapy24 and remains the basis for current futility research.10, 14 Achievement of prehospital ROSC after OHCA is one of the most crucial prehospital variables for predicting favorable neurological outcomes.14, 25 Furthermore, as EMS providers in Japan are not allowed to terminate resuscitation in the field, almost all OHCA patients are transported to hospitals even though more than 90% of those patients do not achieve prehospital ROSC.15 Therefore, to estimate the critical duration of prehospital CPR provided by EMS personnel, we calculated the CPR duration needed to achieve a cumulative proportion >99% for 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes in patients who had prehospital ROSC after OHCA.

Previous studies26, 27 have shown that patients with an initial nonshockable rhythm were older and had a longer CPR duration compared to patients with an initial shockable rhythm, results that are consistent with the present study (Table 1). Moreover, we found that when comparing patients with initial asystole to those with other initial rhythms, the CPR duration yielding 99% of 1‐month survivors was longer than for patients with initial VF/pulseless VT or PEA (ie, 39 minutes for asystole versus 35 minutes for VF/pulseless VT and 34 minutes for PEA). In patients with a nonshockable initial rhythm, epinephrine administration by EMS personnel plays an important role in achieving prehospital ROSC.28 As shown in Table 1, the proportion of epinephrine administration for patients with an initial nonshockable rhythm, particularly in the asystole cohort, was significantly higher than for those in the initial VF/pulseless VT cohort (P for trend <0.001).

In addition, several pre‐, intra‐, and postarrest factors (eg, sex, comorbidities, witnessed status, and the introduction of therapeutic hypothermia) may also have influenced CPR duration before ROSC. Of these, therapeutic hypothermia and extracorporeal CPR (ECPR) after arrival at the hospitals may be crucial to both survival and survival with favorable neurological outcomes. However, we lacked precise data regarding how these advanced therapies were related to outcomes. During the course of the present study, from 2011 to 2012, in‐hospital therapies for CPR were performed according to the 2010 Japanese Guideline for Emergency Care and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.17 Therefore, use of these advanced therapies remained unchanged for the 2‐year study period.

In general, refractory cardiac arrest is thought to be present if patients with OHCA do not achieve a sustained ROSC despite extensive or prolonged resuscitation. Therefore, clinical decision‐making should be required before the critical CPR duration is surpassed. Namely, the physician in charge of medical control should decide whether to withhold or terminate resuscitation efforts, to continue conventional CPR, or to deploy ECPR after hospital arrival. As noted above, termination of prehospital CPR by EMS providers at the scene is legally prohibited in Japan, and most patients with OHCA are transported to hospitals; therefore, we developed and validated a termination‐of‐resuscitation rule for emergency department physicians that is applied soon after arrival of an OHCA patient.14 The rule14 predicts extremely poor outcomes in >99% of cases when the following 3 criteria are met: (1) prehospital ROSC was not achieved, (2) the patient had a nonshockable initial rhythm, and (3) the cardiac arrest was unwitnessed by bystanders. Accordingly, if an OHCA patient is transported to the hospital and meets the criteria of the aforementioned termination‐of‐resuscitation rule,14 the emergency department physician may decide to withhold or terminate resuscitation with more confidence by referring to the critical prehospital CPR duration for survival (39 minutes for initial asystole and 34 minutes for initial PEA). This may be particularly useful in areas where no termination‐of‐resuscitation rules are applied at the scene, as in Japan. However, the clinician in charge must recognize that do‐not‐resuscitate orders may not match the postcardiac arrest prognosis.29 For example, Fendler et al29 demonstrated that only 36% of patients with the worst prognosis obtained do‐not‐resuscitate orders after ROSC from an in‐hospital cardiac arrest. Therefore, a more accurate prognostication tool as well as adequate communication with family members to help them understand the prognosis is needed to facilitate shared, informed decision‐making.

Furthermore, published reports of the indications for ECPR in OHCA patients vary.30, 31, 32, 33 For example, Kim et al30 showed that the optimal time for considering ECPR as an alternative method to conventional CPR should be within 21 minutes. In addition, the authors report that ECPR should be implemented after 40 minutes of CPR duration. Similarly, French medical scientific societies have recommended that ECPR should be considered in patients with a refractory cardiac arrest surpassing 30 minutes.9 Kagawa et al31 implemented ECPR after 20 minutes of conventional CPR for cases of suspected cardiac origin in patients with VF. Sakamoto et al32 conducted ECPR in patients with initial VF/pulseless VT typically within 15 minutes after arrival to the hospital and within ≈45 to 60 minutes from the onset of cardiac arrest. Kim et al33 demonstrated that, among adult OHCA patients who were treated with mild therapeutic hypothermia, a substantial number of survivors with good neurological outcomes existed even with a collapse‐to‐ROSC time (downtime) >30 minutes. Particularly, 40% of patients (4/10) with a shockable rhythm and a much longer downtime (>30 minutes; median 45 minutes; 25–75%: 40.0–65.0 minutes) had a CPC 1–2 at hospital discharge. Taking into account these studies, merely extending conventional CPR would not benefit those requiring prolonged CPR after OHCA. Notably, results for the initial VF/pulseless VT cohort in the present study indicate that a CPR duration of 35 minutes may be a critical transition time for deploying ECPR combined with mild therapeutic hypothermia if OHCA patients with an initial shockable rhythm do not achieve ROSC before arrival to the hospital.

Limitations

There are some potential limitations in the present observational study. First, we did not evaluate in‐hospital treatments, such as induced hypothermia, ECPR, and administration of drugs (eg, epinephrine), which may have affected the results. We assumed that the patients with OHCA received standard advanced life support according to the Japanese CPR guidelines.17 Second, although we used a uniform data‐collection procedure based on Utstein‐style guidelines for reporting cardiac arrest as well as a large sample size and a population‐based design, we cannot exclude the possibility of uncontrolled confounders. For example, as we lacked data on items such as pre‐existing comorbidity, the location where cardiac arrest occurred, and the quality of bystander CPR, we could not include these data in our analyses. It is now clear that the quality of both bystander and EMS CPR will have a substantial effect on survival. An EMS program of frequent retraining and monitoring of CPR quality is needed to optimize CPR performance and survival. Third, as with all epidemiological studies, an ascertainment bias as well as lack of integrity and validity of the data are potential limitations. Fourth, to elucidate the critical prehospital duration of CPR performed by EMS providers in the field, we focused on patients who had achieved prehospital ROSC after OHCA. For this reason, we excluded OHCA patients who had not achieved prehospital ROSC (more than 80% of all OHCA patients during the study period). Further prospective study that includes such patients is required to determine the relationship between CPR duration and outcomes. Finally, the relevance of our results for other communities with different emergency care protocols remains unknown. Therefore, studies in other countries may be required to validate our results.

Conclusions

CPR duration was independently and inversely associated with 1‐month survival and 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes after OHCA. The critical prehospital CPR duration for OHCA, which was needed to achieve prehospital ROSC and produce >99% of OHCA patients with 1‐month survival with favorable neurological outcomes, was 35 minutes in patients with shockable rhythms and PEA, and 42 minutes in those with initial asystole.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Grant Number 15K08543), which had no role in the design and implementation of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002819 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002819)

References

- 1. Ro YS, Shin SD, Kitamura T, Lee EJ, Kajino K, Song KJ, Nishiyama C, Kong SY, Sakai T, Nishiuchi T, Hayashi Y, Iwami T; Seoul‐Osaka Resuscitation Study Group . Temporal trends in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest survival outcomes between two metropolitan communities: Seoul‐Osaka resuscitation study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan PS, McNally B, Tang F, Kellermann A; CARES Surveillance Group . Recent trends in survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation. 2014;130:1876–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong MK, Morrison LJ, Qiu F, Austin PC, Cheskes S, Dorian P, Scales DC, Tu JV, Verbeek PR, Wijeysundera HC, Ko DT. Trends in short‐ and long‐term survival among out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest patients alive at hospital arrival. Circulation. 2014;130:1883–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nitta M, Nagao K, Nonogi H, Yonemoto N, Kimura T; for the Japanese Circulation Society Resuscitation Science Study Group . Nationwide improvements in survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Japan. Circulation. 2012;126:2834–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen YS, Lin JW, Yu HY, Ko WJ, Jerng JS, Chang WT, Chen WJ, Huang SC, Chi NH, Wang CH, Chen LC, Tsai PR, Wang SS, Hwang JJ, Lin FY. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with assisted extracorporeal life‐support versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults with in‐hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study and propensity analysis. Lancet. 2008;372:554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shih CL, Lu TC, Jerng JS, Linc CC, Liua YP, Chena WJ, Lind FY. A web‐based Utstein style registry system of in‐hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Taiwan. Resuscitation. 2007;72:394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Le Guen M, Nicolas‐Robin A, Carreira S, Raux M, Leprince P, Riou B, Langeron O. Extracorporeal life support following out‐of‐hospital refractory cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2011;15:R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation: 2005 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2005;112(suppl III):III‐1–III‐136. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Riou B, Adnet F, Baud F, Cariou A, Carli P, Combes A, Devictor D, Dubois‐Randé JL, Gérard JL, Gueugniaud PY, Ricard‐Hibon A, Langeron O, Leprince L, Longrois D, Pavie A, Pouard P, Rozé JC, Trochu JN, Vincentelli A. Guidelines for indications for the use of extracorporeal life support in refractory cardiac arrest. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2009;28:182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrison LJ, Kierzek G, Diekema DS, Sayre MR, Silvers SM, Idris AH, Mancini ME. Part 3: Ethics. 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S665–S675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morrison LJ, Visentin LM, Kiss A, Theriault R, Eby D, Vermeulen M, Sherbino J, Verbeek PR; for the TOR investigators . Validation of a rule for termination of resuscitation in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atkins DL. Doing the same thing over and over, yet expecting different results. Circulation. 2013;128:2465–2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mancini ME, Diekema DS, Hoadley TA, Kadlec KD, Leveille MH, McGowan JE, Munkwitz MM, Panchal AR, Sayre MR, Sinz EH. Part 3: Ethical issues. 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132:S383–S396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goto Y, Maeda T, Goto NY. Termination‐of‐resuscitation rule for emergency department physicians treating out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest patients: an observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goto Y, Maeda T, Nakatsu‐Goto Y. Neurological outcomes in patients transported to hospital without a prehospital return of spontaneous circulation after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2013;17:R274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jacobs I, Nadkami V, Bahr J, Berg RA, Billi JE, Bossaert L, Cassan P, Coovadia A, D'Este K, Finn J, Halperin H, Handley A, Herlitz J, Hickey R, Idris A, Kloeck W, Larkin GL, Mancini ME, Mason P, Mears G, Monsieurs K, Montgomery W, Morley P, Nichol G, Nolan J, Okada K, Perlman J, Shuster M, Steen PA, Sterz F, Tibballs J, Timerman S, Truitt T, Zideman D. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Inter American Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa). Circulation. 2004;110:3385–3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Japan Resuscitation Council CPR Guidelines Committee . 2010 Japanese Guidelines for Emergency Care and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. 1st ed Tokyo: Health Shuppansha; 2011. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nagao K, Tanaka H, Hiraide A; for the Implementation Working Group for All‐Japan Utstein Registry of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency . Nationwide public access defibrillation in Japan. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schultz SC, Cullinane DC, Pasquale MD, Magnant C, Evans SR. Predicting in‐hospital mortality during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1996;33:13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hajbaghery MA, Mousavi G, Akbari H. Factors influencing survival after in‐hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;66:317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goldberger ZD, Chan PS, Berg RA, Kronick SL, Cooke CR, Lu M, Banerjee M, Hayward RA, Krumholz HM, Nallamothu BK; American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines—Resuscitation (formerly National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) Investigators . Duration of resuscitation efforts and survival after in‐hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Lancet. 2012;380:1473–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reynolds JC, Frisch A, Rittenberger JC, Callaway CW. Duration of resuscitation efforts and functional outcome after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: when should we change to novel therapies? Circulation. 2013;128:2488–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arima T, Nagata O, Sakaida K, Miura T, Kakuchi H, Ikeda K, Mizushima T, Takahashi A. Relationship between duration of prehospital resuscitation and favorable prognosis in ventricular fibrillation. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schneiderman LJ, Jecker NS, Jonsen AR. Medical futility: its meaning and ethical implications. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sasson C, Rogers MAM, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Cir Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim F, Nichol G, Maynard C, Hallstrom A, Kudenchuk PJ, Rea T, Copass MK, Carlbom D, Deem S, Longstreth WT Jr, Olsufka M, Cobb LA. Effect of prehospital induction of mild hypothermia on survival and neurological status among adults with cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frydland M, Kjaergaard J, Erlinge D, Wanscher M, Nielsen N, Pellis T, Åneman A, Friberg H, Hovdenes J, Horn J, Wetterslev J, Winther‐Jensen M, Wise MP, Kuiper M, Stammet P, Cronberg T, Gasche Y, Hassager C. Target temperature management of 33°C and 36°C in patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest with initial non‐shockable rhythm—a TTM sub‐study. Resuscitation. 2015;89:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goto Y, Maeda T, Goto YN. Effects of prehospital epinephrine during out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest with initial non‐shockable rhythm: an observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fendler TJ, Spertus JA, Kennedy KF, Chen LM, Perman SM, Chan PS; for the American Heart Association's Get With the Guidelines‐Resuscitation Investigators . Alignment of do‐not‐resuscitate status with patients’ likelihood of favorable neurological survival after in‐hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2015;314:1264–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim SJ, Jung JS, Park JH, Park JS, Hong YS, Lee SW. An optimal transition time to extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for predicting good neurological outcome in patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: a propensity‐matched study. Crit Care. 2014;18:535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kagawa E, Dote K, Kato M, Sasaki S, Nakano Y, Kajikawa M, Higashi A, Itakura K, Sera A, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Kurisu S. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiac arrest? Rapid‐response extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and intra‐arrest percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2012;126:1605–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sakamoto T, Morimura N, Nagao K, Asai Y, Yokota H, Nara S, Hase M, Tahara Y, Atsumi T; SAVE‐J Study Group . Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: a prospective observational study. Resuscitation. 2014;85:762–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim WY, Giberson TA, Uber A, Berg K, Cocchi MN, Donnino MW. Neurologic outcome in comatose patients resuscitated from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest with prolonged downtime and treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1042–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]