The authors applied the previously validated venous thromboembolism Clinical Risk Score to 4,405 adults with solid tumors or lymphoma initiating chemotherapy. Risk scores were predictive of early mortality and cancer progression during the first four cycles of outpatient chemotherapy. High-risk patients had 120-day mortality rates of 12.7% and cancer progression rates of 27.2%; intermediate-risk patients, 5.9% and 16.4%, respectively; and low-risk patients, 1.4% and 8.5%.

Keywords: Neoplasms, Thromboembolism, Survival, Mortality, Drug therapy, Outpatients

Abstract

Background.

Retrospective studies have suggested an association between cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) and patient survival. We evaluated a previously validated VTE Clinical Risk Score in also predicting early mortality and cancer progression.

Methods.

A large, nationwide, prospective cohort study of adults with solid tumors or lymphoma initiating chemotherapy was conducted from 2002 to 2006 at 115 U.S. practice sites. Survival and cancer progression were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. Multivariate analysis was based on Cox regression analysis adjusted for major prognostic factors including VTE itself.

Results.

Of 4,405 patients, 134 (3.0%) died and 330 (7.5%) experienced disease progression during the first 4 months of therapy (median follow-up 75 days). Patients deemed high risk (n = 540, 12.3%) by the Clinical Risk Score had a 120-day mortality rate of 12.7% (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.4–6.3), and intermediate-risk patients (n = 2,665, 60.5%) had a mortality rate of 5.9% (aHR 2.3, 95% CI 1.2–4.4) compared with only 1.4% for low-risk patients (n = 1,200, 27.2%). At 120 days of follow-up, cancer progression occurred in 27.2% of high-risk patients (aHR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4–3.5) and 16.4% of intermediate-risk patients (aHR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–2.7) compared with only 8.5% of low-risk patients (p < .0001).

Conclusion.

The Clinical Risk Score, originally developed to predict the occurrence of VTE, is also predictive of early mortality and cancer progression during the first four cycles of outpatient chemotherapy, independent from other major prognostic factors including VTE itself. Ongoing and future studies will help determine the impact of VTE prophylaxis on survival.

Implications for Practice:

The risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is increased in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. In this article, the authors demonstrate that a popular risk score for VTE in patients with cancer is also associated with the risk of early mortality in this setting. It is important that clinicians evaluate the risk of VTE in patients receiving cancer treatment and discuss the risk and associated symptoms of VTE with patients. Individuals at increased risk should be advised that VTE is a medical emergency and should be urgently diagnosed and appropriately treated to reduce the risk of serious and life-threatening complications.

Introduction

The risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is increased in patients with malignant disease and rises progressively over the course of treatment [1–3]. VTE has been associated with worsened short- and long-term outcomes in patients with cancer in retrospective studies [4, 5]. Part of this association can be explained by vascular events directly leading to mortality, such as pulmonary embolism [6]. In addition, however, activation of coagulation is observed in many cancer patients even in the absence of clinical symptoms. Emerging basic science data suggest that the hemostatic system is activated by oncogenes and that its components are involved in multiple interactions with transformed cells that allow for progression from a dormant, nonvascularized tumor to highly metastatic phenotypes [7].

Early mortality, variably defined as death occurring within 30–120 days after initiating chemotherapy, occurs in 1% to as high as 23% of patients initiating systemic therapy [6, 8–11]. Reported rates vary widely based on the population characteristics, including cancer site, stage, and type of treatment. In a French cohort study of 1,051 cancer patients, 4.1% experienced mortality within 31 days of starting chemotherapy [8, 12]. In an analysis of all-cause mortality in 1,720 patients with gastrointestinal cancers treated in randomized studies at the Royal Marsden Hospital, 60-day rates varied from 0.2% for patients with adjuvant colorectal cancer to as high as 12.9% for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer [11]. In other trials of systemic therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer, 90-day mortality rates have continued to range from 4% to 6% across various study arms [9, 10].

Despite the known risk of early treatment-associated mortality and its impact on patients as well as on new drug development, studies focusing on risk factors for early mortality are limited. Although stage and performance status are typically used to predict outcomes, patients with the same stage can have widely varying outcomes. Low performance status is generally reported to predict for poor outcomes [8, 13–16]. However, performance status relies on subjective reporting by patients and providers [17]. Investigators from the ELYPSE (Lercanidipine Effectiveness and Safety Profile) study group reported on a risk assessment model to identify patients at risk for early death [8]. However, the study relied on patients enrolled between 1985 and 1997, and the contemporary relevance of the findings is not known.

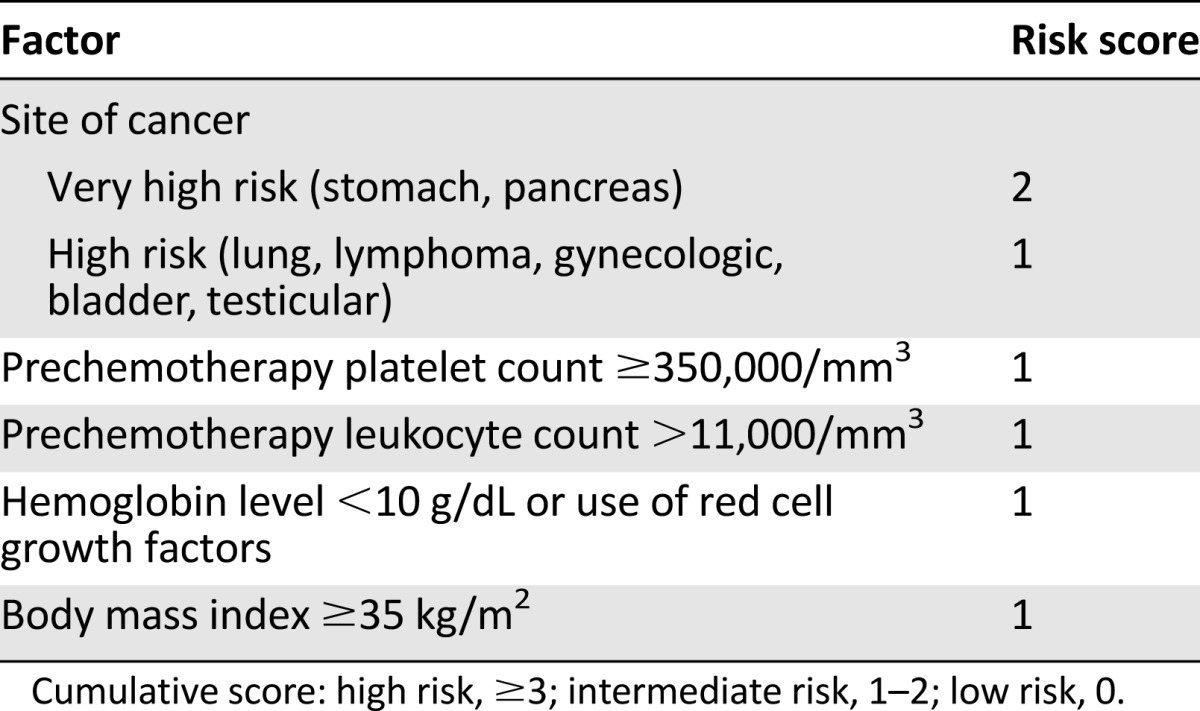

We previously developed a Clinical Risk Score to identify patients receiving chemotherapy who are at high risk for VTE [18]. This VTE Clinical Risk Score relies on five readily available clinical variables including primary site of cancer, prechemotherapy platelet and leukocyte counts, prechemotherapy hemoglobin or use of red cell growth factors, and body mass index (Table 1). This Clinical Risk Score was initially externally validated in a prospective population by the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study in 819 cancer patients [19]. The score was also found to be the only predictor of VTE in an analysis of 1,412 patients enrolled in phase I studies [20]. Multiple retrospective and prospective studies have further validated this risk score for VTE [21], and it has been incorporated into several guidelines for risk assessment for VTE in patients with cancer, including those from the American Society of Clinical Oncology [22–25]. However, its value in predicting other cancer outcomes, including mortality and cancer progression, has not previously been studied.

Table 1.

Clinical Risk Score

Given the proposed impact of VTE on the survival of cancer patients, we evaluated the ability of the Clinical Risk Score to predict patients at risk for early mortality and early cancer progression while on systemic chemotherapy.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

The population studied was based on a large U.S., nationwide, multicenter, prospective cohort study designed to evaluate chemotherapy-related complications and cancer outcomes in representative U.S. ambulatory patients with cancer. From March 2002 to October 2006, patients were consecutively recruited at 115 randomly selected U.S. oncology practice sites, balanced for practice volume and geographic location, accruing 4,405 adult patients with solid tumors or malignant lymphoma initiating a new chemotherapy regimen. This patient cohort has been described previously [18, 26–28]. Detailed demographic, clinical, and treatment-related measures were prospectively captured at baseline and during the first four cycles of chemotherapy, including rates of VTE and deaths from all causes. The study was approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board, as well as a central institutional review board for each respective study site.

Eligible patients were age 18 or older without an upper age limit. Further eligibility criteria included a histologically confirmed diagnosis of solid tumor with particular focus on breast, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer or lymphoma. Eligible patients from other tumor sites were allowed. In addition, patients had to have a life expectancy of at least 3 months, plan to initiate chemotherapy for at least four cycles, and provide written, informed consent.

Patients were not eligible if they were to receive concurrent cytotoxic, biologic, or immunologic therapy for other conditions or were participating in blinded clinical trials of known myelosuppressive drugs. Patients were ineligible if they planned or had a history of stem cell transplantation; had acute leukemia or a myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative disorder; were pregnant or lactating; or had an active infection.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcomes consisted of overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and disease progression (DP). Time was measured from day 1 of the first cycle of chemotherapy until the relevant event (death from any cause for OS, death from any cause or progression for PFS, and progression for DP). Deaths attributed to disease progression were also included among events of disease progression. Causes of death and disease progression were determined by the treating physician. Patients without an event were censored at the end of study or the last date of follow-up. The cumulative incidence of events at 120 days was estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier.

VTE and the Clinical Risk Score

Symptomatic VTE (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) was diagnosed by standard diagnostic criteria by the treating physician as described in detail previously [1, 18]. OS, PFS, and the proportion free of DP were estimated at 120 days using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients were stratified according to Clinical Risk Score into three risk groups as previously described (low, intermediate, and high [18]). Kaplan-Meier estimates of the primary outcomes and associated hazard ratios (HRs) were generated, comparing the high- and intermediate-risk groups to the low-risk group.

Univariable Analysis

The total proportion of patients with VTE, death, progression, and death or progression during the study overall and within several clinically relevant patient characteristics was estimated. The association of relevant patient characteristics with the primary outcomes was evaluated in univariable analysis. The proportions of events in the groups with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using normal approximation and p values determined by χ2 test.

Multivariable Analysis

Multivariable regression analysis based on the method of Cox was used to study the association of the Clinical Risk Score or VTE with the primary outcomes adjusted for other risk factors. These included age, race, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index for cancer patients, body mass index, cancer type and stage, number and type of chemotherapy agents, relative dose intensity (RDI) of chemotherapy treatment regimen, and year of study. Model covariates were determined a priori before the analysis based on clinical relevance for study outcomes. The model incorporated VTE as a time-dependent covariate. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by log(−log([survival])) versus log(time) plots. To evaluate the linearity assumption for continuous covariates, a quadratic term was entered into the regression. No deviation from linearity was determined. Clinically relevant interactions between risk factors were explored, and no significant interactions were found. The adjusted hazard ratios for VTE and the risk score, 95% CI, and p values were determined using Wald χ2 test. p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html).

Results

Patient Characteristics

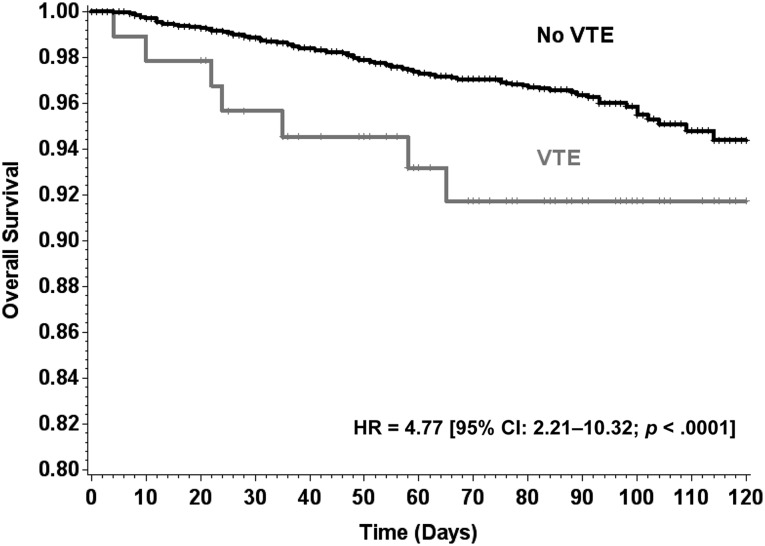

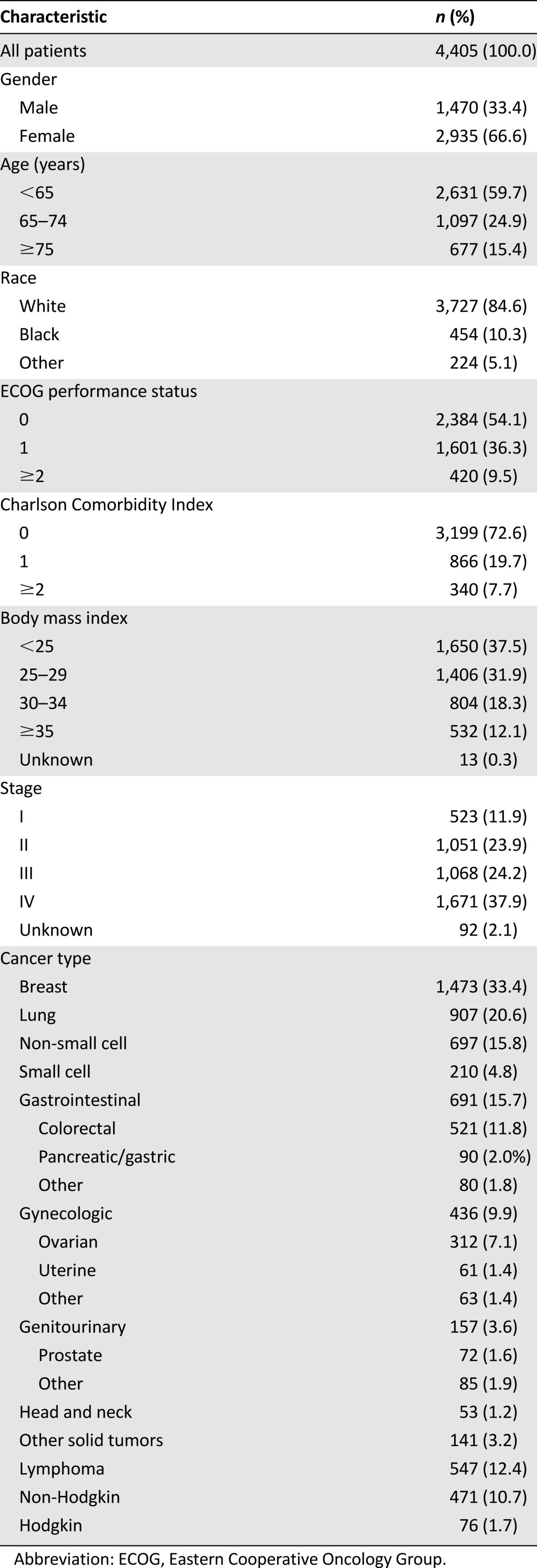

The study population comprised 4,405 ambulatory patients with cancer initiating a new chemotherapy regimen (Table 2). The average age was 60 years (range 18–97). Primary diagnoses included cancers of the breast (33%), colon/rectum (12%), lung (21%), gastric/pancreas (2%), lymphoma (12%), and others (20%), with 38% having stage IV disease. Overall, 134 patients died during the period of observation, and 330 experienced disease progression, with a median follow-up of 75 days (interquartile range 44–88) after the initiation of chemotherapy (Table 2). VTE occurred in 93 (2.1%) patients and was associated with significantly greater mortality than patients without VTE (HR 4.8 [95% CI 2.2–10.3], p < .0001) (Fig. 1). Unadjusted (crude) cumulative risk over the study period was 3.0% (95% CI 2.5–3.5) for mortality, 7.5% (95% CI 6.7–8.3) for disease progression, and 8.3% (95% CI 7.5–9.1) for progression or death. Kaplan-Meier estimates of mortality and disease progression at 120 days are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in patients with and without VTE. Patients with VTE were found to have worse prognosis than patients without VTE (HR 4.8 [95% CI 2.2–10.3], p < .0001). HR for impact of VTE on overall survival was calculated based on the Cox model, considering VTE as a time-dependent covariate.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

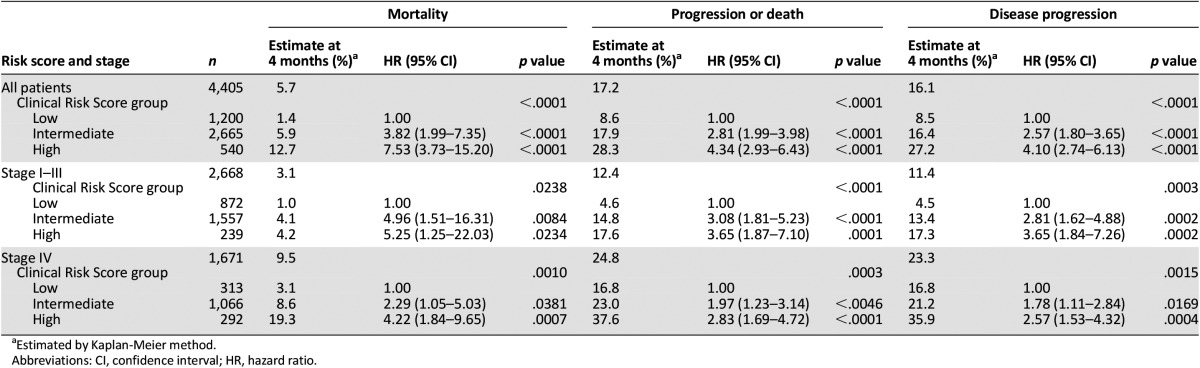

Table 3.

Overall survival, progression-free survival, and disease progression by Clinical Risk Score and stage

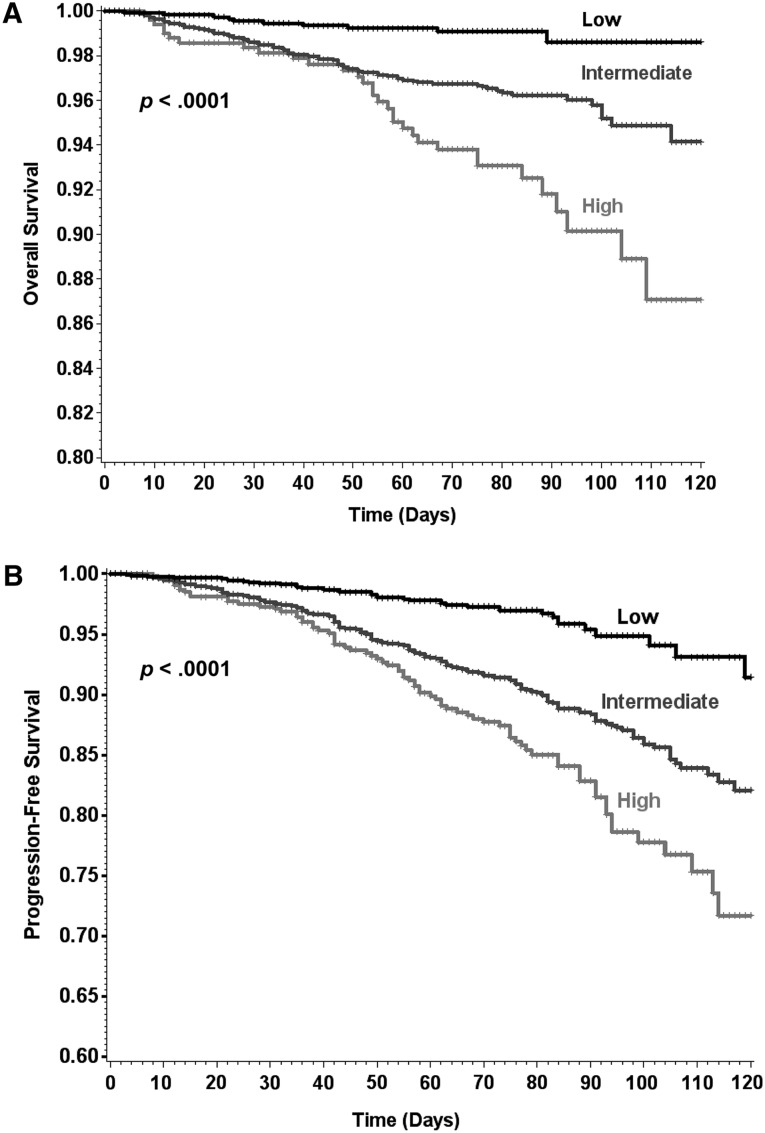

Clinical Risk Score and Mortality

Based on the Clinical Risk Score, 1,200 patients (27.2%) were classified as low risk, 2,665 (60.5%) as intermediate risk, and 540 (12.3%) as high risk. Based on Kaplan-Meier estimates, all-cause mortality during the first four cycles of chemotherapy occurred in 1.4%, 5.9%, and 12.7% of low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients, respectively (Table 3). Compared with low-risk patients, OS was decreased for both intermediate-risk (HR 3.8 [95% CI 2.0%–7.4%], p < .0001) and high-risk (HR 7.5 [95% CI 3.7%–15.2%], p < .0001) patients (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall and progression-free survival according to Clinical Risk Score group. (A): Overall survival. (B): Progression-free survival. Patients with intermediate or high risk based on Clinical Risk Score stratification were found to have worse prognosis than low-risk patients (p < .0001 for both).

Among deceased patients, the cause of death was attributed to progressive disease in 82%, 63%, and 66% of low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients, respectively. Among 1,671 patients with metastatic disease, mortality rates were 19.3% for high-risk (HR 4.2 [95% CI 1.8–9.7]) and 8.6% for intermediate-risk (HR 2.3 [95% CI 1.1–5.0]) patients compared with 3.1% for low-risk patients.

Clinical Risk Score and Disease Progression

Compared with low-risk patients, an increase in disease progression or death was observed among both intermediate-risk (HR 2.8 [95% CI 2.0–4.0], p < .0001) and high-risk (HR 4.3 [95% CI 2.9–6.4], p < .0001) patients as determined by the Clinical Risk Score (Table 3), resulting in estimates of death or disease progression in 8.6%, 17.9%, and 28.3% of low-, intermediate-, and high-risk patients (Fig. 2B). In patients with metastatic disease, disease progression occurred in 35.9% of high-risk (HR 2.6 [95% CI 1.5–4.3]), 21.2% of intermediate-risk (HR 1.8 [95% CI 1.1–2.8]), and 16.8% of low-risk patients. The association between the Clinical Risk Score and OS, PFS, and DP was also significant when analyses were limited to only metastatic or only early-stage patient populations (Table 3).

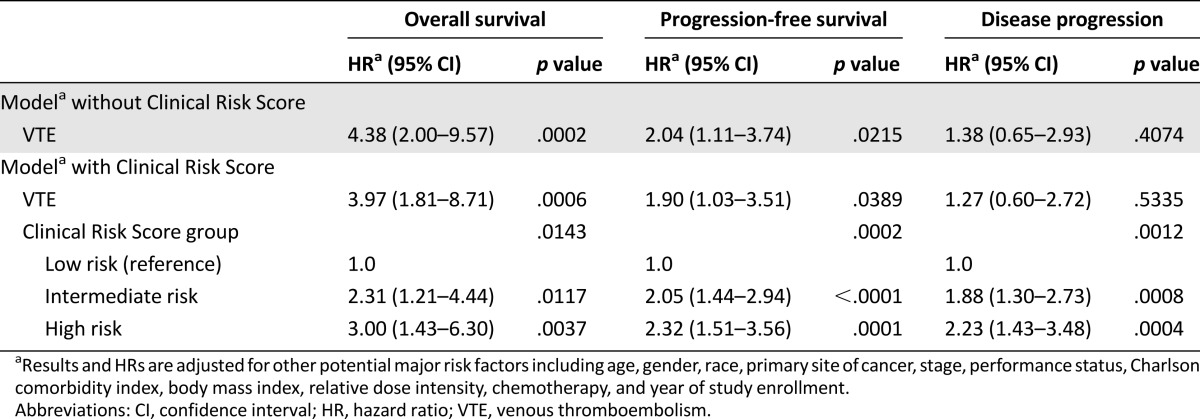

Multivariable Analysis

In multivariable Cox regression analysis, the Clinical Risk Score continued to be significantly associated with mortality after adjusting for the occurrence of VTE itself as well as other major prognostic factors determined a priori, including age, gender, race, cancer type, stage, ECOG performance status, adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index, body mass index, chemotherapy and chemotherapy relative dose intensity, and year of study enrollment (Table 4). Compared with low-risk patients, intermediate- and high-risk patients as determined by the score had 2.3- and 3.0-fold higher risks of mortality, respectively.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of the impact of VTE and Clinical Risk Score group on overall survival, progression-free survival, and disease progression

In multivariable analysis after adjusting for the same major prognostic factors, VTE remained an independent risk factor for reduced PFS (2.04 [95% CI 1.11–3.74], p = .022) (Table 4). In addition, after adjustment, both VTE (p = .039) and the risk score (p = .0002) remained independently associated with decreased PFS. However, in concurrence with the univariable analysis, the risk score (p = .0012), but not VTE (p = .534), was an independent predictor for disease progression. Compared with low-risk patients, intermediate- and high-risk patients as determined by the Clinical Risk Score experienced 2.1- and 2.3-fold lower PFS and 1.9- and 2.2-fold higher risks of disease progression, respectively.

Discussion

In this large U.S. prospective cohort study of outpatients initiating systemic chemotherapy, the previously validated VTE Clinical Risk Score was also found to be predictive of early all-cause mortality as well as early disease progression and progression-free survival. Further, VTE is seen to be an independent risk factor for reduced overall and progression-free survival during cancer chemotherapy. The strong association of the Clinical Risk Score with mortality and cancer progression during the first few cycles of chemotherapy persists even after adjusting for VTE as a time-dependent covariate, as well as other prognostic and potential confounding factors including age, gender, race, cancer type, stage, performance status, adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index, chemotherapy, and chemotherapy dose intensity. Although VTE does not appear to be associated with subsequent disease progression, the Clinical Risk Score remains an independent risk factor for disease progression in cancer patients in multivariate analysis. Thus, the Clinical Risk Score comprising five readily available clinical and laboratory variables represents a comprehensive risk assessment tool that could help identify outpatients receiving systemic chemotherapy at risk for early all-cause mortality and disease progression.

The cause of early death, which is difficult to confirm in the absence of an autopsy, can broadly be categorized as cancer-related (primarily from cancer progression), vascular syndrome-related (including venous and arterial thromboembolic events) and treatment-related (including infectious complications and gastrointestinal syndromes). In the French cohort study, 53% of deaths occurring in the first 31 days were categorized as vascular or treatment related (including septic shock, cardiac failure, and pulmonary embolism), and 47% were considered to be secondary to progressive disease [8]. In a prior analysis of the current prospective cohort population, cancer progression was the cause of death in a majority of cases, with thrombotic events and infection tied as second-leading causes of death [6]. In the independent panel investigation of C89803 and N9741, a majority of early deaths were found to be treatment related, although the panel included both vascular syndrome-related and other gastrointestinal toxicities in this category [12]. In the Royal Marsden cohort, 90% of deaths in advanced colon and pancreatic cancer were cancer related, but in contrast all deaths in patients with resected colon cancer were vascular syndrome related [11]. The Clinical Risk Score is significantly predictive of both cancer progression and vascular syndromes and may, therefore, be uniquely capable of capturing early treatment-related mortality. The individual parameters contributing to the Clinical Risk Score have been associated with mortality in cancer patients [1, 29, 30]. Certainly, primary site of cancer plays an important role in determining prognosis. In addition, pretreatment anemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis have previously all been shown to be associated with mortality in various solid tumors, including colorectal, cervical, and gastric cancers [31–33]. Obesity has also been recognized as a prognostic factor for colorectal and breast cancers [34–36]. Thus, the results reported here are consistent with and build on findings from previous epidemiologic studies.

One potential hypothesis to explain the association of the Clinical Risk Score with VTE, early mortality, and disease progression is the possibility that the score identifies patients harboring more aggressive tumor biology. In this context, it is important to note that alterations of the hemostatic system are frequently found in cancer patients, even in the absence of a diagnosis of VTE [37–41]. Additional ties between the hemostatic system and tumor cell have been observed, including fibrinogen deposits surrounding the tumor cells and tumor tissue bed [42, 43]. There is mounting evidence that components of the coagulation cascade and associated hemostatic factors play an integral part in tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis [44–46]. In addition, multiple retrospective studies have previously suggested that patients with both cancer and VTE have worse survival [6, 47–49]. Unfortunately, these studies did not have detailed clinical information and were not able to adjust for most major prognostic factors for survival. This current analysis confirms these findings in the setting of detailed, prospectively collected clinical data adjusted for major prognostic factors and extends the findings to the early period of treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with both early-stage and advanced cancer.

Limitations of this cohort study need to be taken into consideration in interpretation of the results presented here. Although this study was prospective in design, as in any nonrandomized study, the potential for confounding from unmeasured and unknown prognostic factors remains despite adjustment for major clinical prognostic factors as well as laboratory results. Importantly, VTE was not the primary outcome of this prospective cohort study, potentially leading to underreporting and less accurate distinction between patients with VTE and controls. This could lead to bias in the study toward a lower effect size difference between VTE and non-VTE cancer patients. Disease progression was defined by treating providers and not by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria. However, treating providers were blinded to the planned analyses of the study population. As with any risk assessment tool, validation in external populations is essential. In this regard, it is important to note recent data from the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study study confirming the association of the Clinical Risk Score with mortality [50].

Conclusion

The results presented here demonstrate that this validated VTE Clinical Risk Score is highly predictive of early mortality as well as early disease progression in patients initiating systemic cancer chemotherapy. The risk score comprises readily available clinical and laboratory measures and is, therefore, a cost-effective, clinically applicable tool available at the point of care. Furthermore, this study confirms that VTE is an independent risk factor for mortality and progression-free survival during the course of cancer chemotherapy. Ongoing and future randomized trials will help determine the impact of VTE prophylaxis on survival and disease progression in ambulatory patients with malignant disease.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Nicole M. Kuderer, Eva Culakova, Gary H. Lyman, Charles Francis, Anna Falanga, Alok A. Khorana

Provision of study material or patients: Gary H. Lyman

Collection and/or assembly of data: Eva Culakova, Gary H. Lyman

Data analysis and interpretation: Nicole M. Kuderer, Eva Culakova, Gary H. Lyman, Alok A. Khorana

Manuscript writing: Nicole M. Kuderer, Eva Culakova, Gary H. Lyman, Charles Francis, Anna Falanga, Alok A. Khorana

Final approval of manuscript: Nicole M. Kuderer, Eva Culakova, Gary H. Lyman, Charles Francis, Anna Falanga, Alok A. Khorana

Disclosures

Nicole M. Kuderer: Janssen (C/A); Charles Francis: Lilly (C/A), Eisai (RF); Alok A. Khorana: Janssen, Leo, Sanofi, Halozyme, Angiodynamics, Genentech, Pfizer (C/A, H), Janssen, Leo, Amgen (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, et al. Risk factors for chemotherapy-associated venous thromboembolism in a prospective observational study. Cancer. 2005;104:2822–2829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyman GH. Venous thromboembolism in the patient with cancer: Focus on burden of disease and benefits of thromboprophylaxis. Cancer. 2011;117:1334–1349. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyman GH. The incidence of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: A real-world analysis. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10:40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sørensen HT, Mellemkjaer L, Olsen JH, et al. Prognosis of cancers associated with venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1846–1850. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khorana AA, Rosenblatt JD, Sahasrabudhe DM, et al. A phase I trial of immunotherapy with intratumoral adenovirus-interferon-gamma (TG1041) in patients with malignant melanoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:251–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, et al. Thromboembolism is a leading cause of death in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:632–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruf W. Tissue factor and cancer. Thromb Res. 2012;130(suppl 1):S84–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.08.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray-Coquard I, Ghesquière H, Bachelot T, et al. Identification of patients at risk for early death after conventional chemotherapy in solid tumours and lymphomas. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:816–822. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539–1544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katopodis O, Ross P, Norman AR, et al. Sixty-day all-cause mortality rates in patients treated for gastrointestinal cancers, in randomised trials, at the Royal Marsden Hospital. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2230–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothenberg ML, Meropol NJ, Poplin EA, et al. Mortality associated with irinotecan plus bolus fluorouracil/leucovorin: Summary findings of an independent panel. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3801–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.18.3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morittu L, Earl HM, Souhami RL, et al. Patients at risk of chemotherapy-associated toxicity in small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:801–804. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komaki R, Pajak TF, Byhardt RW, et al. Analysis of early and late deaths on RTOG non-small cell carcinoma of the lung trials: Comparison with CALGB 8433. Lung Cancer. 1993;10:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(93)90179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez H, Hidalgo M, Casanova L, et al. Risk factors for treatment-related death in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Results of a multivariate analysis. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2065–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sargent DJ, Köhne CH, Sanoff HK, et al. Pooled safety and efficacy analysis examining the effect of performance status on outcomes in nine first-line treatment trials using individual data from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1948–1955. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, et al. A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327:195–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111:4902–4907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ay C, Dunkler D, Marosi C, et al. Prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Blood. 2010;116:5377–5382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandala M, Clerici M, Corradino I, et al. Incidence, risk factors and clinical implications of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients treated within the context of phase I studies: The ‘SENDO experience.’. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1416–1421. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khorana AA. Cancer and coagulation. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(suppl 1):S82–S87. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2189–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streiff MB, Bockenstedt PL, Cataland SR, et al. Venous thromboembolic disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1402–1429. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuderer NM, Lyman GH. Guidelines for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism among patients with cancer. Thromb Res. 2014;133(suppl 2):S122–S127. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(14)50021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyman GH, Bohlke K, Khorana AA, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update 2014. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:654–656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2522–2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shayne M, Culakova E, Wolff D, et al. Dose intensity and hematologic toxicity in older breast cancer patients receiving systemic chemotherapy. Cancer. 2009;115:5319–5328. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crawford J, Dale DC, Kuderer NM, et al. Risk and timing of neutropenic events in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: The results of a prospective nationwide study of oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:109–118. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Blumberg N, et al. Blood transfusions, thrombosis, and mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2377–2381. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly GC, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, et al. Leukocytosis, thrombosis and early mortality in cancer patients initiating chemotherapy. Thromb Res. 2010;126:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu MZ, Yuan ZY, Luo HY, et al. Impact of pretreatment hematologic profile on survival of colorectal cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2010;31:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda M, Furukawa H, Imamura H, et al. Poor prognosis associated with thrombocytosis in patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02573067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes A, Daras V, Cross PA, et al. Thrombocytosis as a prognostic factor in women with cervical cancer. Cancer. 1994;74:90–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940701)74:1<90::aid-cncr2820740116>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Curtis KM, et al. Body mass and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2009–2014. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Sargent DJ, et al. Obesity is an independent prognostic variable in colon cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1884–1893. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rickles FR, Levine M, Edwards RL. Hemostatic alterations in cancer patients. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:237–248. doi: 10.1007/BF01307180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rickles FR, Levine MN. Venous thromboembolism in malignancy and malignancy in venous thromboembolism. Haemostasis. 1998;28(suppl 3):43–49. doi: 10.1159/000022404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldenberg N, Kahn SR, Solymoss S. Markers of coagulation and angiogenesis in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4194–4199. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sallah S, Husain A, Wan J, et al. The risk of venous thromboembolic disease in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1490–1494. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyman GH, Bettigole RE, Robson E, et al. Fibrinogen kinetics in patients with neoplastic disease. Cancer. 1978;41:1113–1122. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197803)41:3<1113::aid-cncr2820410346>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dvorak HF, Senger DR, Dvorak AM. Fibrin as a component of the tumor stroma: Origins and biological significance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1983;2:41–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00046905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dvorak HF, Nagy JA, Berse B, et al. Vascular permeability factor, fibrin, and the pathogenesis of tumor stroma formation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;667:101–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb51603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browder T, Folkman J, Pirie-Shepherd S. The hemostatic system as a regulator of angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1521–1524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Liu H, et al. Plasminogen supports tumor growth through a fibrinogen-dependent mechanism linked to vascular patency. Blood. 2003;102:2819–2827. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horowitz NA, Blevins EA, Miller WM, et al. Thrombomodulin is a determinant of metastasis through a mechanism linked to the thrombin binding domain but not the lectin-like domain. Blood. 2011;118:2889–2895. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:458–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Komrokji RS, Uppal NP, Khorana AA, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1029–1033. doi: 10.1080/10428190600560991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and trends for venous thromboembolism among hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer. 2007;110:2339–2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay C, Reitter EM, Riedl J et al. A risk scoring model for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism is predictive for overall survival in patients with cancer. Abstract presented at: XXIV International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostatis Congress; July 3, 2013; Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]