The overall survival of patients with mucosal, uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary metastatic melanoma has not been directly compared. A retrospective analysis of 3,454 patients with melanoma and distant metastases was conducted. Patients with mucosal melanoma had inferior overall survival. Additional research and advocacy are needed for patients with mucosal melanoma because of their shorter overall survival in the metastatic setting.

Keywords: Mucosal melanoma, Uveal melanoma, Acral cutaneous melanoma, Nonacral cutaneous melanoma, Unknown primary melanoma, Prognosis

Abstract

Background.

Subtypes of melanoma, such as mucosal, uveal, and acral, are believed to result in worse prognoses than nonacral cutaneous melanoma. After a diagnosis of distant metastatic disease, however, the overall survival of patients with mucosal, uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma has not been directly compared.

Materials and Methods.

We conducted a single-center, retrospective analysis of 3,454 patients with melanoma diagnosed with distant metastases from 2000 to 2013, identified from a prospectively maintained database. We examined melanoma subtype, date of diagnosis of distant metastases, age at diagnosis of metastasis, gender, and site of melanoma metastases.

Results.

Of the 3,454 patients (237 with mucosal, 286 with uveal, 2,292 with nonacral cutaneous, 105 with acral cutaneous, and 534 with unknown primary melanoma), 2,594 died. The median follow-up was 46.1 months. The median overall survival for those with mucosal, uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma was 9.1, 13.4, 11.4, 11.7, and 10.4 months, respectively. Patients with uveal melanoma, cutaneous melanoma (acral and nonacral), and unknown primary melanoma had similar survival, but patients with mucosal melanoma had worse survival. Patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma in 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 had better overall survival than patients diagnosed in 2000–2005. In a multivariate model, patients with mucosal melanoma had inferior overall survival compared with patients with the other four subtypes.

Conclusion.

Additional research and advocacy are needed for patients with mucosal melanoma because of their shorter overall survival in the metastatic setting. Despite distinct tumor biology, the survival was similar for those with metastatic uveal melanoma, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma.

Implications for Practice:

Uveal, acral, and mucosal melanoma are assumed to result in a worse prognosis than nonacral cutaneous melanoma or unknown primary melanoma. No studies, however, have been conducted assessing the overall survival of patients with these melanoma subtypes starting at the time of distant metastatic disease. The present study found that patients with uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma have similar overall survival after distant metastases have been diagnosed. These findings provide information for oncologists to reconsider previously held assumptions and appropriately counsel patients. Patients with mucosal melanoma have worse overall survival and are thus a group in need of specific research and advocacy.

Introduction

Melanoma most commonly arises from melanocytes present in cutaneous primary locations (cutaneous melanoma), but it can occasionally arise from melanocytes located within the mucosal surfaces of the body (mucosal melanoma) and the uvea of the eye (uveal melanoma). Melanoma can also arise from cutaneous locations in non-hair-bearing surfaces (acral melanoma), such as the palms of the hands, the soles of the feet, or subungual areas. In other cases, melanoma is diagnosed in the metastatic setting without a known primary site (unknown primary melanoma).

Mucosal, uveal, and acral melanoma are far less common than nonacral cutaneous melanoma and have distinct clinical and biological features [1–4]. Cutaneous melanoma has a high frequency of mutations in the oncogene BRAF, and mucosal and acral melanomas have a higher proportion of mutations in the receptor tyrosine kinase protein, KIT [3, 4]. Uveal melanomas, in contrast, have a high proportion of mutations in GNAQ and GNA11, which encode for the α-subunit protein of the heterotrimeric G protein complex activating phospholipase C [5]. The etiology of unknown primary melanoma is not known, but spontaneous regression of an otherwise unrecognized cutaneous melanoma could be involved [6]. The molecular profiles of unknown primary melanoma most closely resemble nonacral cutaneous melanoma, supporting this possibility [7, 8].

It is generally believed that melanoma arising from a mucosal, uveal, or acral cutaneous primary location portends a worse overall prognosis than melanoma arising from a nonacral cutaneous primary location. This assumption has largely been based on studies that have reported high recurrence rates after definitive treatment of primary mucosal, uveal, and acral melanoma and poor overall survival from the time of the diagnosis of primary disease to death [9–14]. Despite these prognostic assumptions, no study, to the best of our knowledge, has evaluated whether the outcomes of patients with these various melanoma subtypes differ after the diagnosis of metastatic disease.

We reviewed the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center experience of patients who had been diagnosed with distant metastatic mucosal, uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma during a 14-year period (2000–2013). We analyzed overall survival among these melanoma subtypes from the time of metastasis diagnosis to death and investigated the relationships between the known prognostic variables and outcome.

Materials and Methods

Patients (n = 3,454) who had been diagnosed with distant metastatic mucosal, uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma were identified from our prospectively maintained melanoma database. The date of diagnosis of distant metastasis was defined as the date distant metastases first appeared clinically or radiographically. The date of each patient’s last known follow-up appointment or death was also recorded. Data on age, gender, treatment with agents known to prolong overall survival in the era of the study (i.e., ipilimumab, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, trametinib, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab), and site of metastases (skin/lymph node involvement, lung metastases, nonpulmonary visceral metastases) were extracted. Patients with mucosal and nonacral cutaneous melanoma were further analyzed according to the specific anatomic subsite of their primary melanoma (mucosal: anorectal, head/neck, vulvovaginal, and other; nonacral cutaneous: scalp, head/neck nonscalp, upper extremity, lower extremity, and trunk). The present retrospective analysis was performed after institutional review board determination that it was exempt research under 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.101.b.

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare the patient and disease characteristics among the melanoma subtypes for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of metastatic diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up visit. The Kaplan-Meier method was used, and comparisons between categorical variables were assessed using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. Because treatment with agents proven to improve overall survival increased over time, most dramatically beginning in 2006 (with U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals starting in 2011), the year of metastatic diagnosis was included as a variable and categorized as 2000–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2013. p values <.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using R, version 3.1.1 (available at https://cran.r-project.org).

Results

Patient Demographics and Treatment

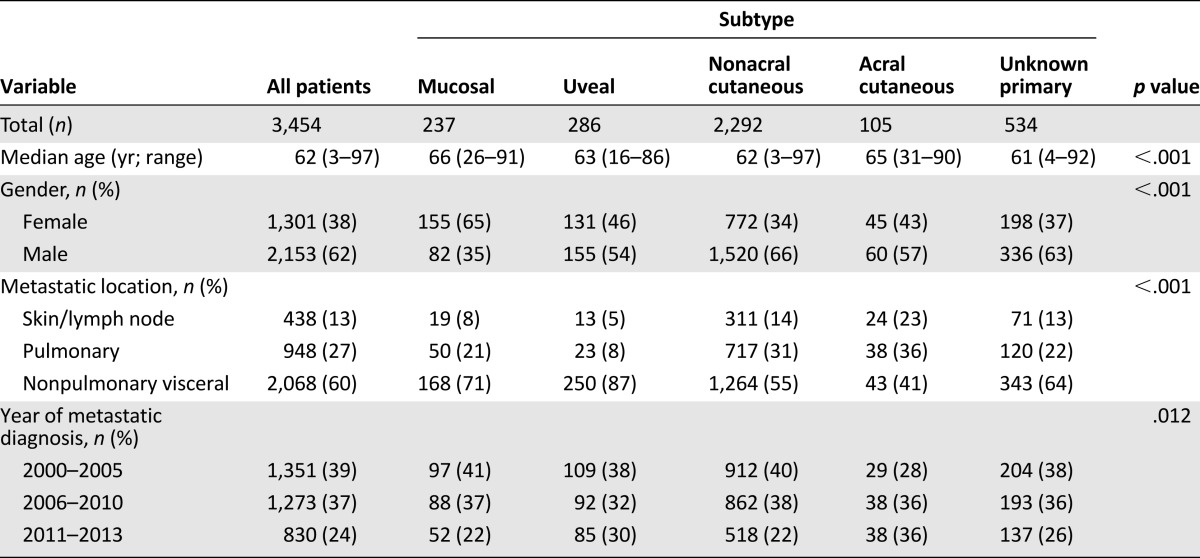

A total of 3,454 patients with metastatic melanoma of primary mucosal (n = 237), uveal (n = 286), acral (n = 105), nonacral cutaneous (n = 2,292), and unknown primary (n = 534) melanoma were included in the present analysis (Table 1). Patients with mucosal melanoma were slightly older, with a median age of 66 years, compared with patients with uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma (median age of 63, 65, 62, and 61 years, respectively; p < .001). More women than men had mucosal melanoma, largely driven by the cases of vulvovaginal melanoma, but more men than women had the other four subtypes (p < .001). Among all melanoma subtypes, the proportion of patients with nonpulmonary visceral metastases (60%) at the time of metastatic diagnosis was greater than that of patients with pulmonary (27%) and skin/lymph node (13%) metastatic melanoma. This difference appeared largest in patients with uveal melanoma, with 87% diagnosed with nonpulmonary visceral melanoma metastases (p < .001). Additional demographic details of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

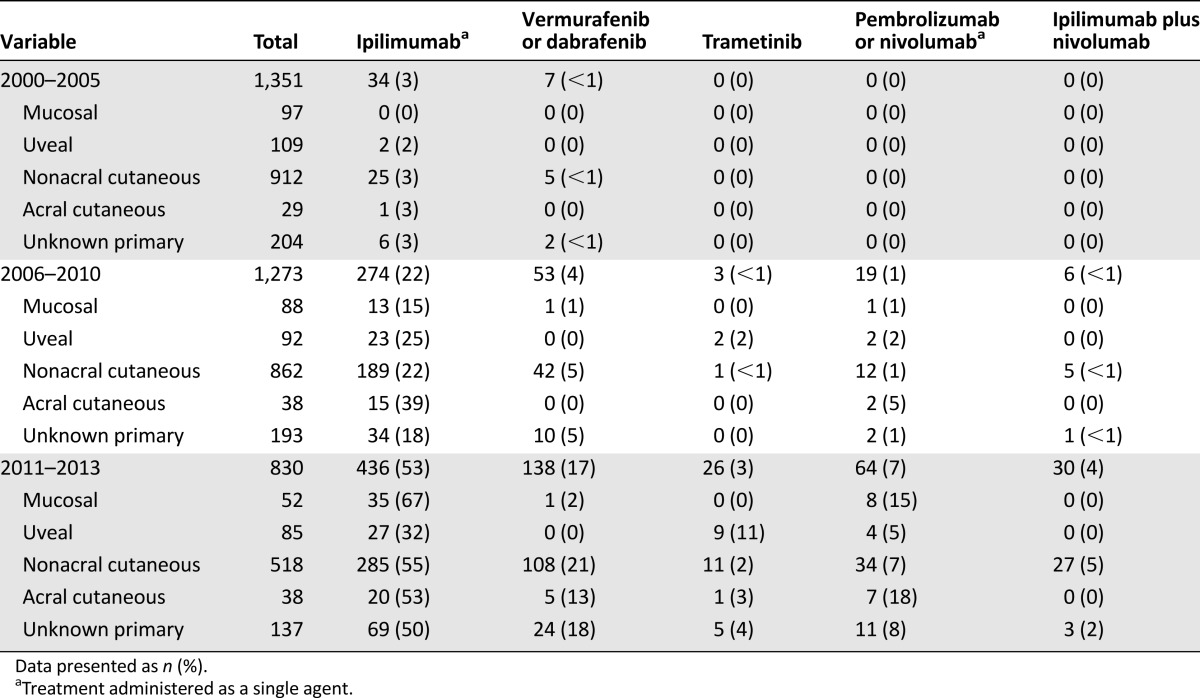

Very few patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma from 2000 to 2005 received treatment shown to improve overall survival (ipilimumab, 3%; RAF inhibitor, <1%; trametinib, 0%; pembrolizumab or nivolumab monotherapy, 0%; Table 2). These proportions differed in the cohort diagnosed with metastatic disease from 2006 to 2010 (ipilimumab, 22%; RAF inhibition, 4%; trametinib, <1%; pembrolizumab or nivolumab monotherapy, 1%, ipilimumab plus nivolumab, <1%) and from 2011 to 2013 (ipilimumab, 53%; RAF inhibitor, 17%; trametinib, 3%; pembrolizumab or nivolumab monotherapy, 7%; ipilimumab plus nivolumab, 4%).

Table 2.

Treatment stratified by melanoma subtype and year of metastatic diagnosis

Univariate Analysis of Overall Survival

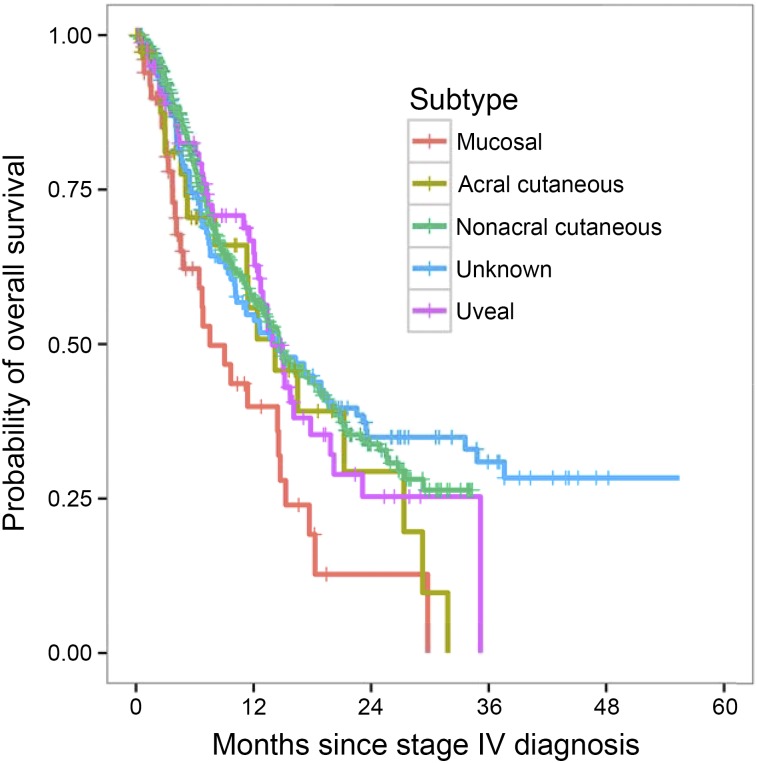

At the last follow-up point, 860 of the 3,454 patients were still alive. The median follow-up period for the survivors was 46.1 months. The median overall survival for the entire cohort of patients was 11.4 months. The univariate analysis results are presented in Table 3. Patients with mucosal melanoma had a significantly shorter median overall survival than that of patients with uveal, acral, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma (9.1, 13.4, 11.4, 11.7, and 10.4 months, respectively; p < .001; Fig. 1). No significant differences were seen in survival between patients with uveal melanoma, both types of cutaneous melanoma (acral and nonacral), and unknown primary melanoma (p = .972). The overall survival also did not differ between those with acral and nonacral cutaneous melanoma (p = .891).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of overall survival

Figure 1.

Overall survival stratified by melanoma subtype in patients with metastatic disease. Patients with mucosal melanoma had shorter overall survival than those with cutaneous, uveal, and unknown primary melanoma (p < .001).

We next sought to determine whether differences could be found in overall survival among patients whose metastatic melanoma had arisen from a specific primary anatomic location. No difference was seen in survival among the specific anatomic subtypes of mucosal melanoma (p = .34; Table 3). However, a significant difference was found in survival among patients with nonacral cutaneous melanoma according to their specific anatomic primary subsite. Patients whose melanoma had originally arisen from a truncal location had worse metastatic overall survival than patients whose cutaneous primary melanoma had arisen from other sites (p = .02; Table 3).

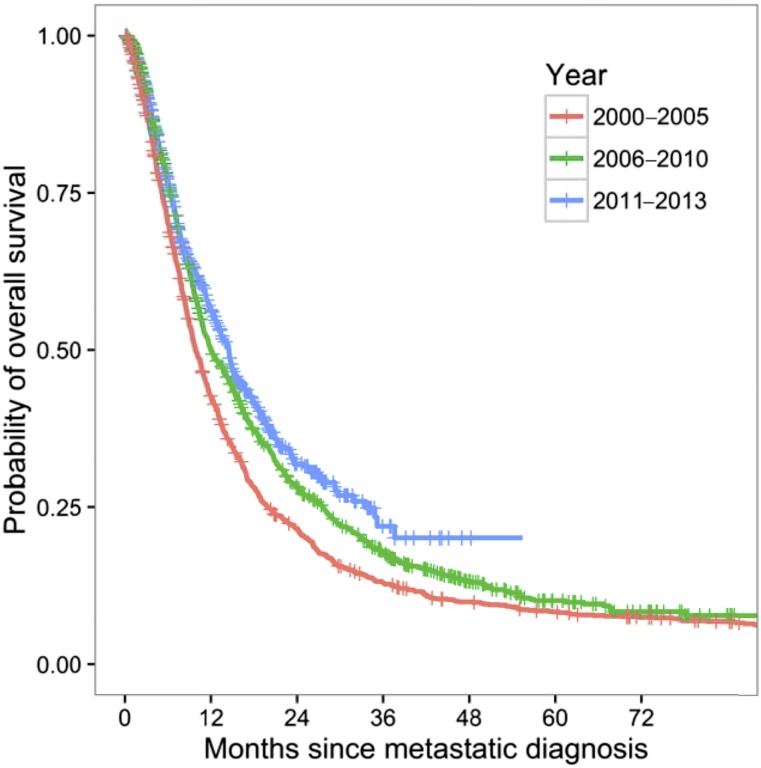

Older age was associated with decreased survival (p < .001). Patients with nonpulmonary visceral metastases had significantly worse survival (8.8 months) than patients with metastatic melanoma involving skin/lymph node (17.5 months) and pulmonary (16.1 months) locations (p < .001). Although a significant difference was found in gender by melanoma subtype, no significant difference was found in survival by gender. Patients whose metastatic diagnosis was in 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 had higher median survival than patients with a metastatic diagnosis in 2000–2005 (median overall survival, 12.0, 14.5, and 9.8 months, respectively; p < .001; Fig. 2). In the 2011–2013 period, the same pattern of survival was observed (Fig. 3). The median overall survival was similar between the uveal and nonacral cutaneous patients (13.9 and 14.7 months, respectively; p = .736), although most of the nonacral cutaneous patients had received immunotherapy or targeted drugs. Patients with mucosal melanoma had significantly worse overall survival (median overall survival, 7.5 months) compared with those with nonacral cutaneous melanoma (p < .001).

Figure 2.

Overall survival stratified by year of metastatic diagnosis. Patients diagnosed in 2000–2005 had shorter overall survival than those diagnosed in 2006 or later (p < .001).

Figure 3.

Overall survival stratified by melanoma subtype in patients with metastatic disease diagnosed in 2011–2013.

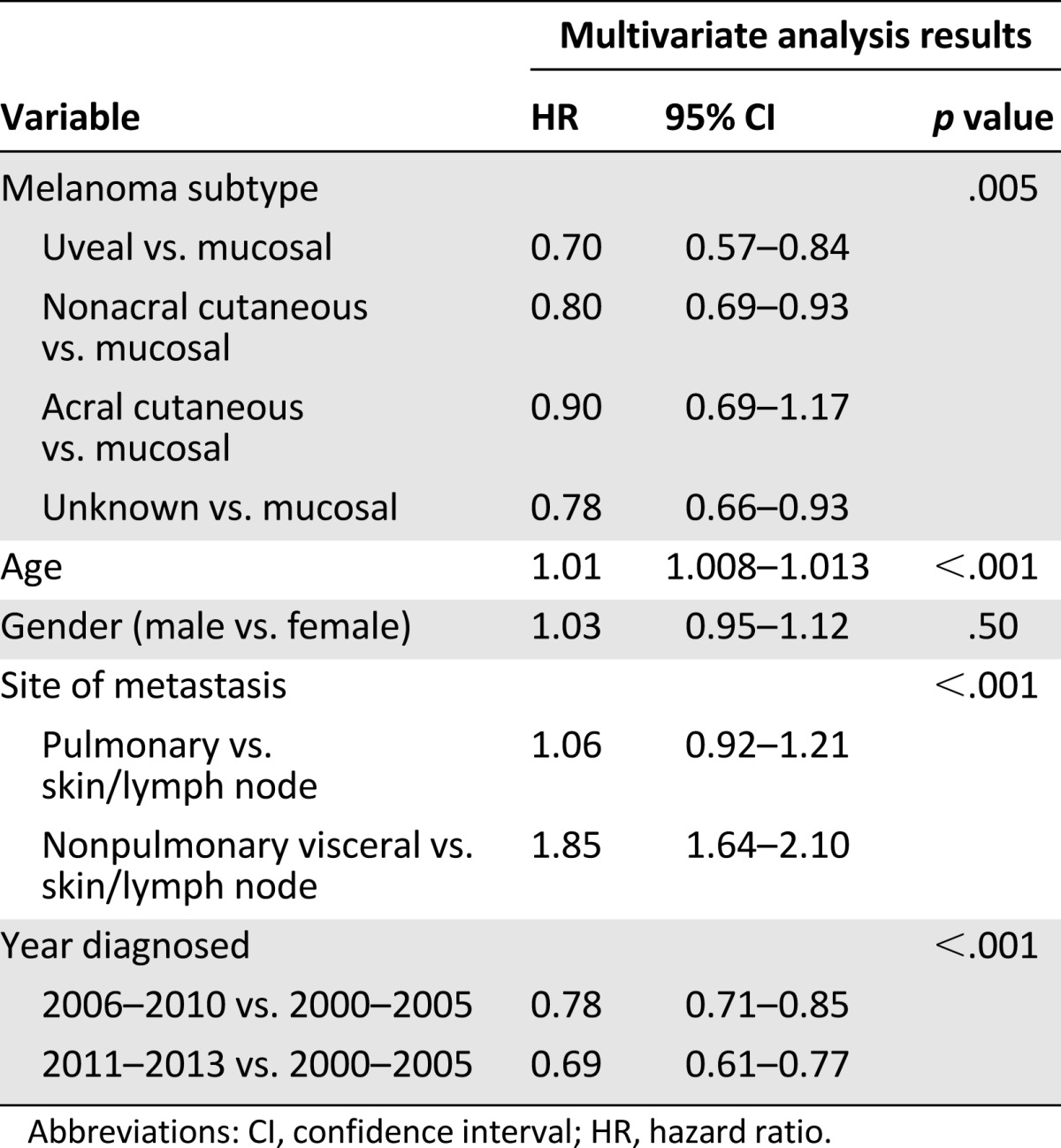

Multivariate Analysis of Overall Survival

Because age, location of metastases, and year of metastatic diagnosis were significantly associated with survival on univariate analysis, these factors were incorporated into a multivariate model. Although gender was not associated with overall survival in our univariate analysis, it was included in the multivariate model, because previous analyses had reported that it was related to the overall survival of patients with melanoma [15, 16].

On multivariate analysis, melanoma subtype, age, site of metastases, and year of metastatic diagnosis were significantly associated with overall survival (Table 4). Similar to the univariate results, those with nonacral cutaneous (hazard ratio [HR], 0.80), uveal melanoma (HR, 0.70), acral cutaneous (HR, 0.90), and unknown primary (HR, 0.78) melanoma had better overall survival than did those with mucosal melanoma.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of overall survival

Discussion

In the present retrospective analysis of nearly 3,500 patients with metastatic melanoma and long-term follow-up data available, we found that metastatic melanoma arising from a primary mucosal site was independently associated with shorter overall survival. Patients with metastatic uveal, acral cutaneous, nonacral cutaneous, and unknown primary melanoma, however, had similar overall survival. Follow-up was complete, with 2,594 deaths (75%) of an initial 3,454 patients at risk, and the median follow-up period for the survivors was long at 46.1 months.

Although other studies have suggested that patients with mucosal, uveal, and acral cutaneous melanoma have a worse prognosis than those with nonacral cutaneous melanoma [9–14], the present study is the only one, to the best of our knowledge, in which the prognosis of metastatic patients with these various melanoma subtypes was directly compared. We found that patients with distant metastatic melanoma of an unknown primary had similar outcomes compared with patients with melanoma of a known primary, consistent with some [17], but not all [18, 19], other studies assessing unknown primary melanoma and melanoma of known primary. Differences in patient numbers and study methods could account for some of the variation.

During the time period of our analysis, several new agents were introduced that were shown to improve overall survival, including ipilimumab [20, 21], vemurafenib [22], dabrafenib [23], trametinib [24], pembrolizumab [25], and nivolumab [26]. It is possible these new treatments affected the improved outcomes seen in the latter time groups, but many factors could have been involved in this finding and the follow-up time was shorter. Nonetheless, when we divided the patients into three subgroups according to the timeframe of their distant disease diagnosis, our main conclusion of the mucosal subtype being associated with shorter overall survival remained unchanged. The finding of worse overall survival for patients with mucosal melanoma compared with nonacral cutaneous melanoma was impressive within the 2011–2013 cohort (7.5 months vs. 14.7 months, respectively; p < .001), suggesting that this difference still seems to exist within more contemporary clinical practice patterns in treatment. Because mucosal and uveal melanomas are associated with a lower frequency of BRAF mutations than cutaneous melanoma [3], the rate of RAF inhibitor use was higher in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Although this might have led to slightly favorable results in the cutaneous group, the rate of RAF inhibitor use was still low, likely because of the historical period when most of these patients were diagnosed with metastatic disease and the unavailability of RAF inhibitors. The use of anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors and the combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab was low in all study periods. Even in the most recent cohort, 2011–2013, although the numbers were small, the use of anti-PD-1 antibodies was not substantially lower in patients with mucosal melanoma to believe this was a reason for their inferior overall survival. When sufficient patients with these melanoma subtypes have been treated with anti-PD-1 approaches with adequate follow-up, a repeat analysis should be performed. For patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, no treatment has yet been shown to improve overall survival and the response rates to standard agents remain low [27–30]. Nonetheless, patients with metastatic uveal melanoma had the same survival as patients with cutaneous melanoma in our data set, possibly suggesting some patients with uveal melanoma have a more indolent disease course.

Because we measured overall survival from the time of metastatic diagnosis to death, we cannot exclude the possibility of a lead-time bias, arising from radiographic surveillance patterns, affecting the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease. However, we do not believe this was the case. Patients with unknown primary melanoma who were not undergoing radiographic surveillance for recurrent melanoma still had more favorable survival than patients with mucosal melanoma. Additionally, radiographic surveillance was not shown to affect the overall survival of patients with recurrent uveal melanoma [31]. The overall survival of patients with metastatic uveal melanoma in the present report was more favorable than that of patients described in other retrospective series [32, 33]. We cannot exclude the possibility of a referral bias contributing to this finding as patients with uveal melanoma sought clinical trials at our institution. Nonetheless, we expect that a similar referral bias should have been present for patients with other melanoma subtypes during this time interval. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and performance status, known prognostic variables in melanoma [34, 35], were not consistently available for all patients and therefore could not be included in the analysis. Thus, we chose to characterize patients by the site of metastatic disease (skin/lymph node, pulmonary, and nonpulmonary visceral) instead of the standard American Joint Committee on Cancer M stage criteria, which requires LDH [35]. Although this was an inherent limitation to our analysis, we believe our findings justify a repeat analysis in a larger data set that includes LDH and performance status for validation.

The reason patients with metastatic mucosal melanoma had worse overall survival remains unclear. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, which has a high somatic mutation rate and mutations associated with exposure to UV light [36, 37], mucosal melanoma has a lower somatic mutation rate with genetic copy number and structural variants that differ from the mutations typically seen in melanomas associated with UV light [38]. It is possible that the unique genetic profile of mucosal melanomas contributes to an inherently more aggressive course than cutaneous melanoma, but this requires further study.

Conclusion

These prognostic findings highlight the need for additional research, patient advocacy, and inclusion in clinical trials of new agents for patients with mucosal melanoma as little is known about the responsiveness of mucosal melanoma to novel melanoma therapeutics. Although metastatic uveal melanoma is believed to be less responsive to systemic therapies than cutaneous melanoma, in our data set, patients with uveal melanoma had the same overall survival as patients with cutaneous melanoma. The prognoses of patients with other malignancies that consist of various subtypes should be similarly investigated from the time of metastatic disease because the prognoses could differ from those when the overall survival from early-stage disease to death is assessed.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Core Grant P30 CA0008748. This work was previously presented in part at the 50th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 30–June 3, 2014.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Deborah Kuk, Richard D. Carvajal, Michael A. Postow

Provision of study material or patients: Alexander N. Shoushtari, Katherine S. Panageas, Mary Sue Brady, Kita Bogatch, Margaret K. Callahan, Jedd D. Wolchok, Richard D. Carvajal, Michael A. Postow

Collection and/or assembly of data: Deborah Kuk, Katherine S. Panageas, Daniel G. Coit, Kita Bogatch, Michael A. Postow

Data analysis and interpretation: Deborah Kuk, Katherine S. Panageas, Kita Bogatch, Richard D. Carvajal, Michael A. Postow

Manuscript writing: Deborah Kuk, Alexander N. Shoushtari, Christopher A. Barker, Katherine S. Panageas, Rodrigo R. Munhoz, Parisa Momtaz, Charlotte E. Ariyan, Mary Sue Brady, Daniel G. Coit, Kita Bogatch, Margaret K. Callahan, Jedd D. Wolchok, Richard D. Carvajal, Michael A. Postow

Final approval of manuscript: Deborah Kuk, Alexander N. Shoushtari, Christopher A. Barker, Katherine S. Panageas, Rodrigo R. Munhoz, Parisa Momtaz, Charlotte E. Ariyan, Mary Sue Brady, Daniel G. Coit, Kita Bogatch, Margaret K. Callahan, Jedd D. Wolchok, Richard D. Carvajal, Michael A. Postow

Disclosures

Alexander N. Shoushtari: Vaccinex (C/A), Bristol-Myers Squibb (RF); Christopher A. Barker: Elekta, Patient Resource (C/A), Elekta (RF); Rodrigo R. Munhoz: Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD (H), Eli Lilly (RF); Margaret K. Callahan: Bristol-Myers Squibb (E [spouse]), Bristol-Myers Squibb (RF); Jedd D. Wolchok: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Medimmune, Genentech, Ziopharm, Polaris, Beigene (RF), Potenza Therapeutics, Tizona Pharmaceuticals (OI); Richard D. Carvajal: Merck, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Janssen (C/A); Michael A. Postow: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Caladrius (C/A), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck (H), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, et al. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer. 2005;103:1000–1007. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: A summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. Cancer. 1998;83:1664–1678. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1664::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, et al. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4340–4346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae JM, Choi YY, Kim DS, et al. Metastatic melanomas of unknown primary show better prognosis than those of known primary: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egberts F, Bergner I, Kruger S, et al. Metastatic melanoma of unknown primary resembles the genotype of cutaneous melanomas. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:246–250. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gos A, Jurkowska M, van Akkooi A, et al. Molecular characterization and patient outcome of melanoma nodal metastases and an unknown primary site. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:4317–4323. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3799-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachar G, Loh KS, O’Sullivan B, et al. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck: Experience of the Princess Margaret Hospital. Head Neck. 2008;30:1325–1331. doi: 10.1002/hed.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frumovitz M, Etchepareborda M, Sun CC, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1358–1365. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fb8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HS, Kim EK, Jun HJ, et al. Noncutaneous malignant melanoma: A prognostic model from a retrospective multicenter study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onken MD, Worley LA, Ehlers JP, et al. Gene expression profiling in uveal melanoma reveals two molecular classes and predicts metastatic death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7205–7209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bello DM, Chou JF, Panageas KS, et al. Prognosis of acral melanoma: A series of 281 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3618–3625. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehra T, Grözinger G, Mann S, et al. Primary localization and tumor thickness as prognostic factors of survival in patients with mucosal melanoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanlorenzo M, Ribero S, Osella-Abate S, et al. Prognostic differences across sexes in melanoma patients: What has changed from the past? Melanoma Res. 2014;24:568–576. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joosse A, Collette S, Suciu S, et al. Sex is an independent prognostic indicator for survival and relapse/progression-free survival in metastasized stage III to IV melanoma: A pooled analysis of five European organisation for research and treatment of cancer randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2337–2346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlagenhauff B, Stroebel W, Ellwanger U, et al. Metastatic melanoma of unknown primary origin shows prognostic similarities to regional metastatic melanoma: Recommendations for initial staging examinations. Cancer. 1997;80:60–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970701)80:1<60::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CC, Faries MB, Wanek LA, et al. Improved survival for stage IV melanoma from an unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3489–3495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vijuk G, Coates AS. Survival of patients with visceral metastatic melanoma from an occult primary lesion: A retrospective matched cohort study. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:419–422. doi: 10.1023/a:1008201931959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luke JJ, Callahan MK, Postow MA, et al. Clinical activity of ipilimumab for metastatic uveal melanoma: A retrospective review of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and University Hospital of Lausanne experience. Cancer. 2013;119:3687–3695. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danielli R, Ridolfi R, Chiarion-Sileni V, et al. Ipilimumab in pretreated patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: Safety and clinical efficacy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1089-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maio M, Danielli R, Chiarion-Sileni V, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in patients with pre-treated, uveal melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2911–2915. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Quevedo JF, et al. Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2397–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rietschel P, Panageas KS, Hanlon C, et al. Variates of survival in metastatic uveal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8076–8080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gragoudas ES, Egan KM, Seddon JM, et al. Survival of patients with metastases from uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, et al. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report 23. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2438–2444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valpione S, Moser JC, Parrozzani R, et al. Development and external validation of a prognostic nomogram for metastatic uveal melanoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furney SJ, Turajlic S, Stamp G, et al. Genome sequencing of mucosal melanomas reveals that they are driven by distinct mechanisms from cutaneous melanoma. J Pathol. 2013;230:261–269. doi: 10.1002/path.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]